Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Soil Metabolic Profiles Across Land Management Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- − Conventional cultivation: N37° 11.9′, W80° 34.5′

- − Organic cultivation: N37° 15.5′, W80° 35.8′

- − Deciduous forest: N37° 15.4′, W80° 35.8′

- − Tulip poplar stand: N37° 15.3′, W80° 35.8′

- − White pine stand: N37° 11.8′, W80° 35.0′

- − Pasture: N37° 12.1′, W80° 34.0′

2.1. Soil Metabolite Extraction

2.2. UPHLC-HRMS Metabolomics Analysis

2.3. Known Spectral Features Processing

2.4. Unidentified Spectral Features

2.5. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

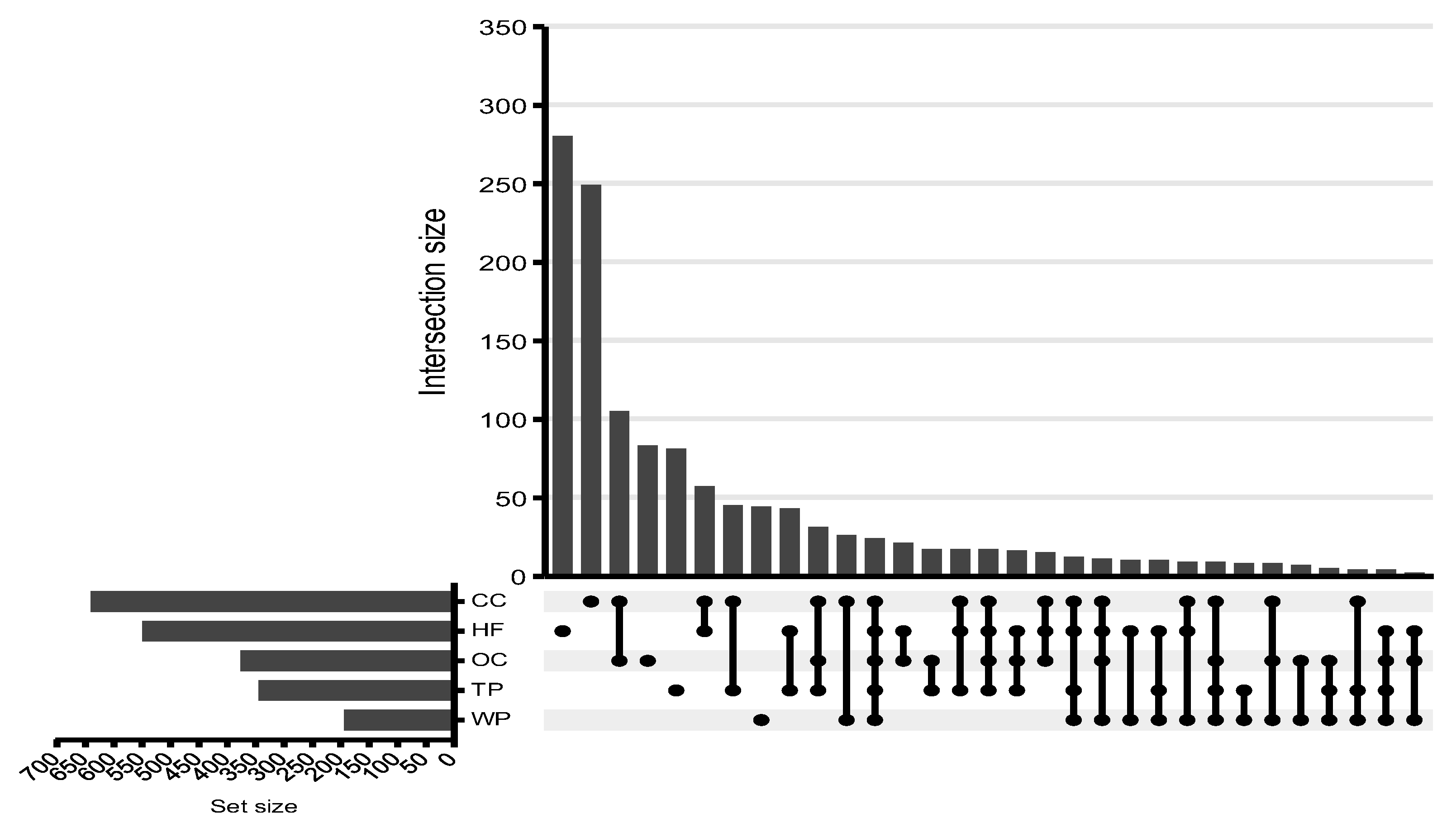

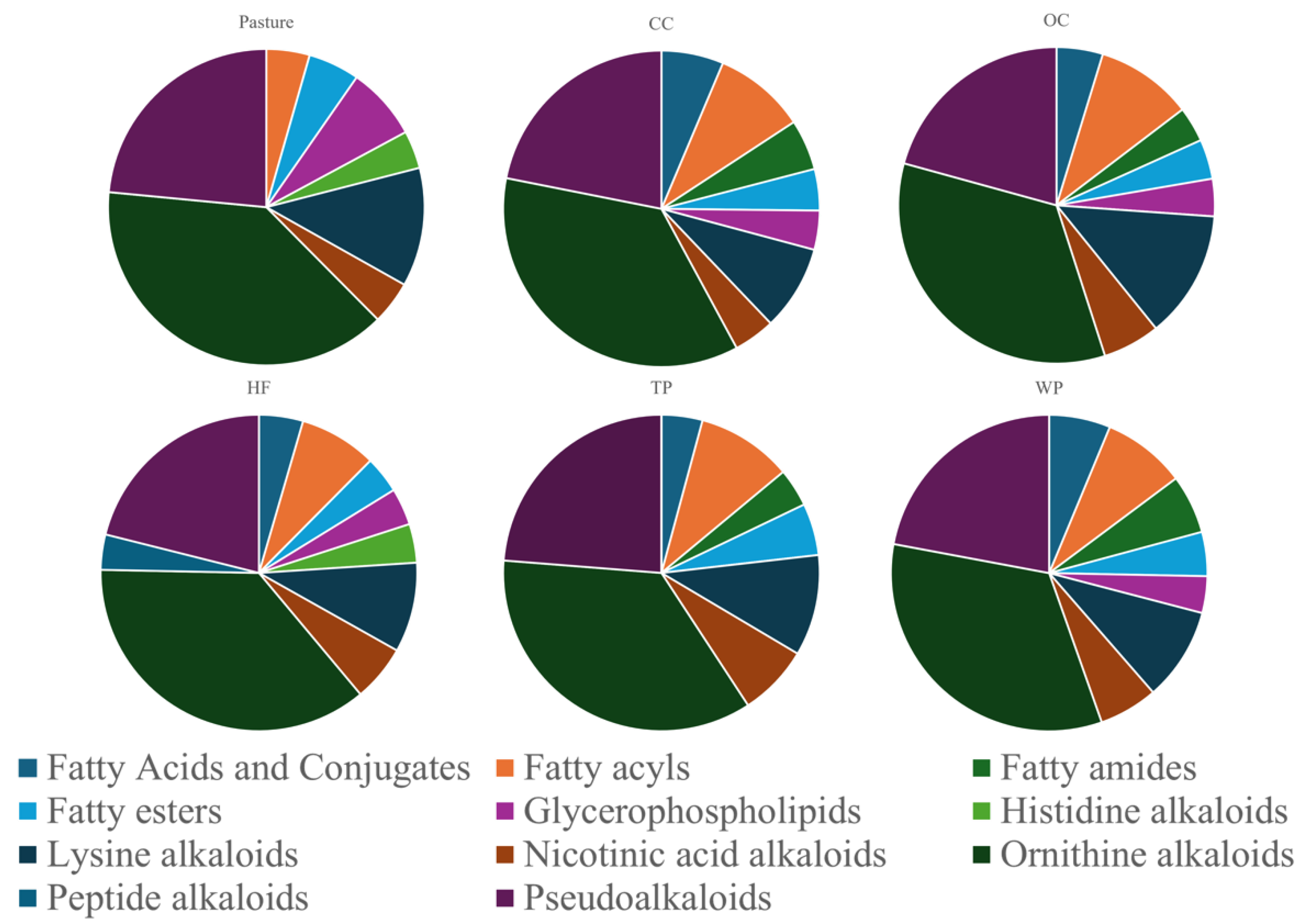

3. Results

4. Discussion

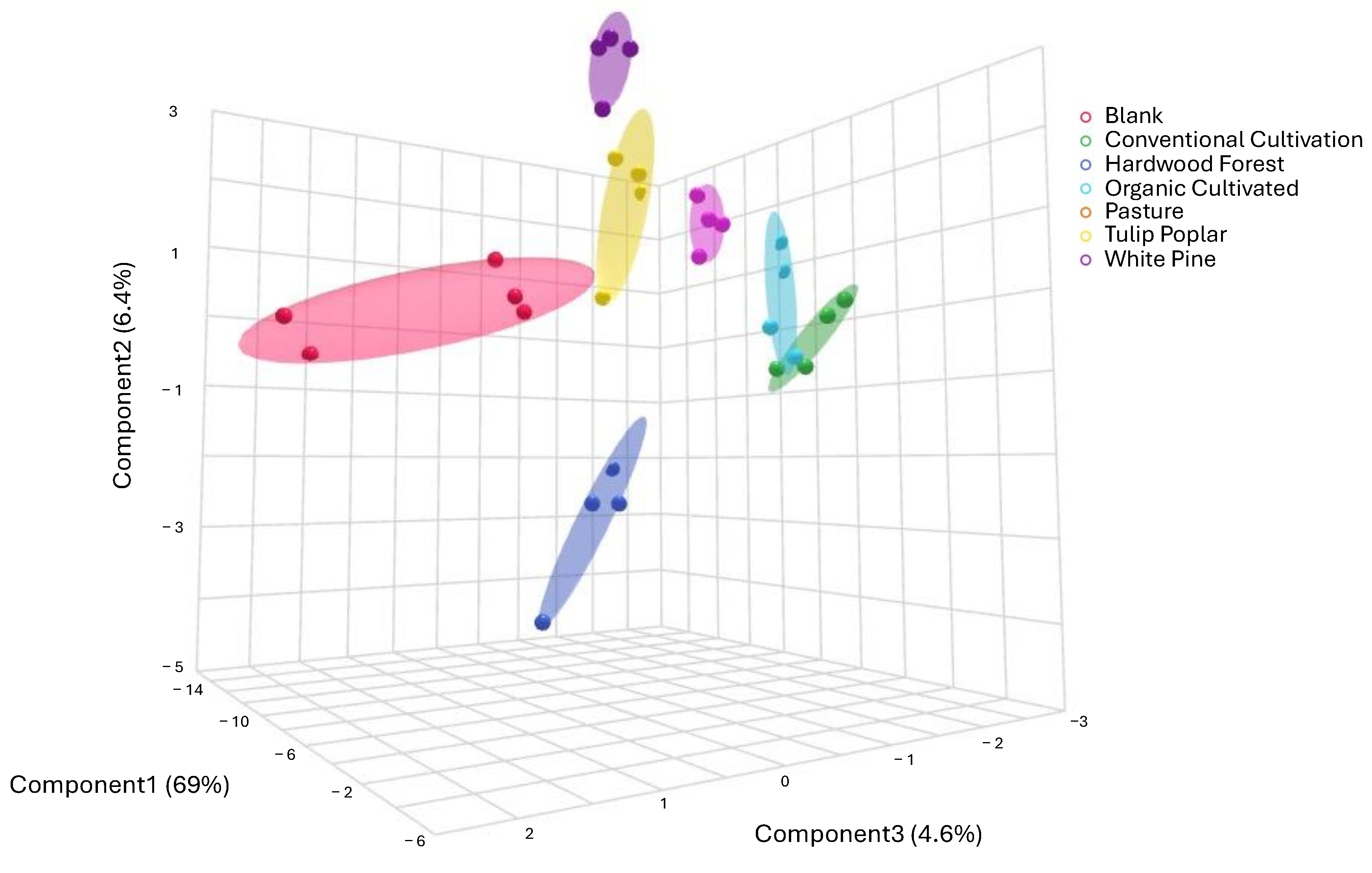

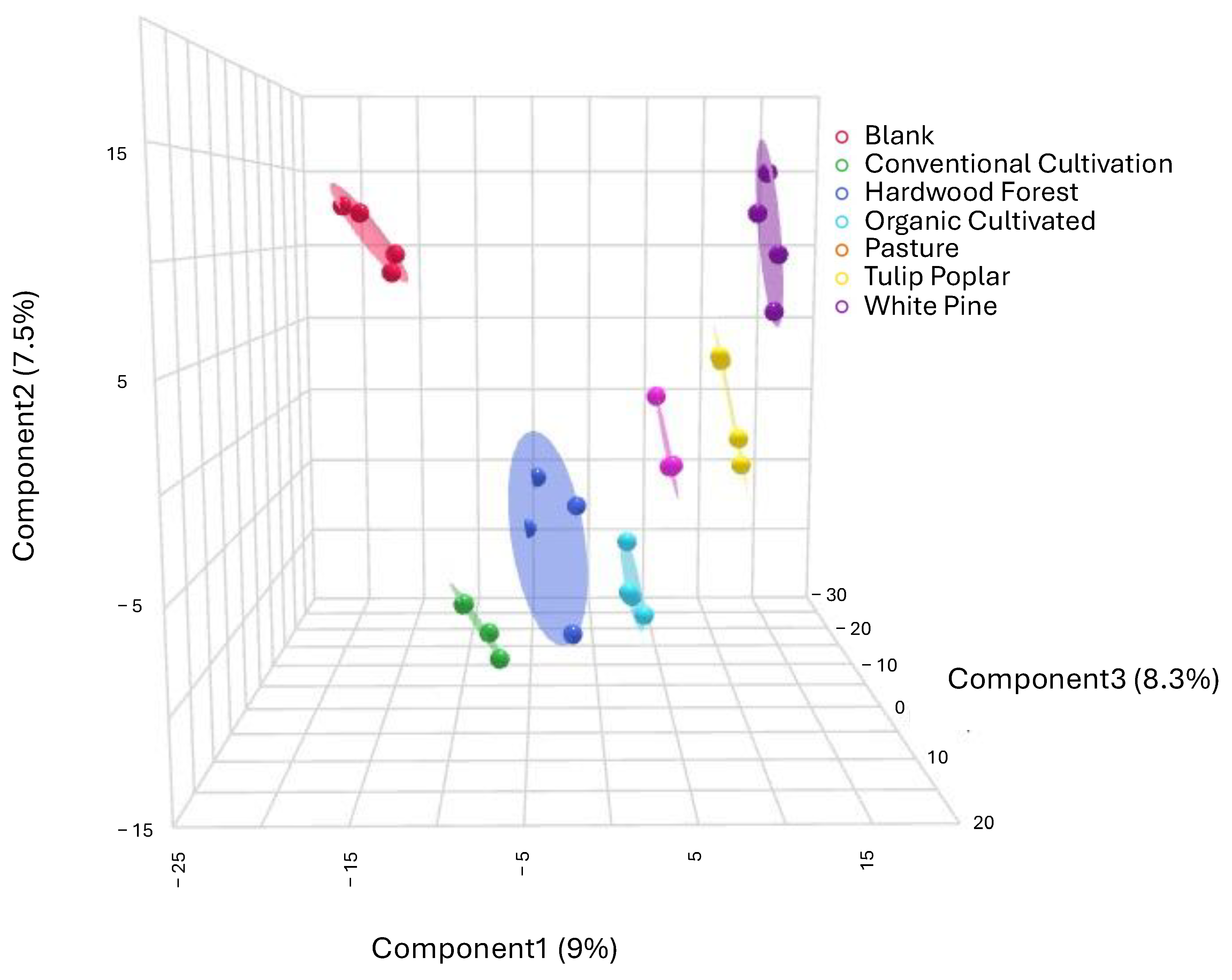

4.1. Metabolic Profiles Are Distinct Across Land Management Practices

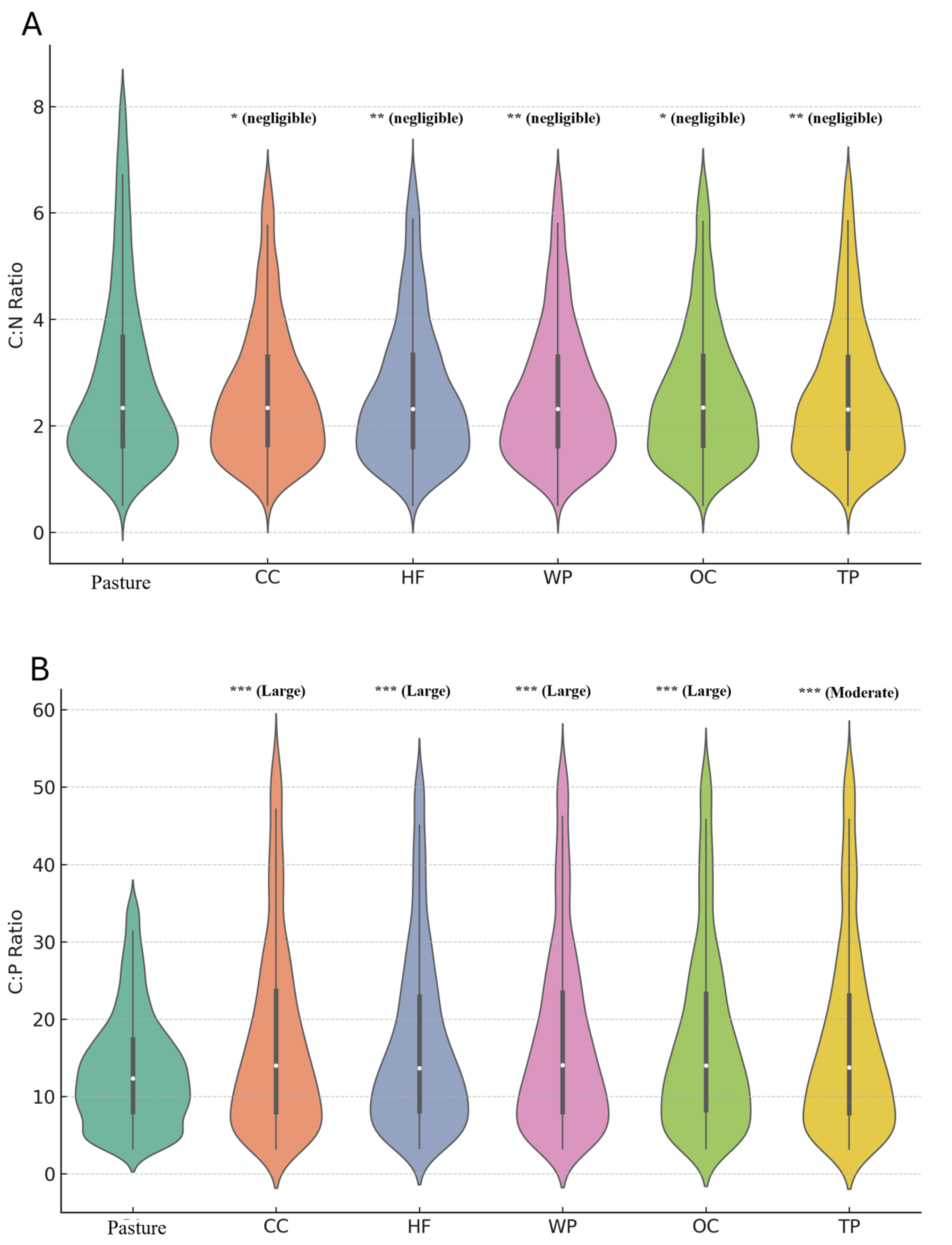

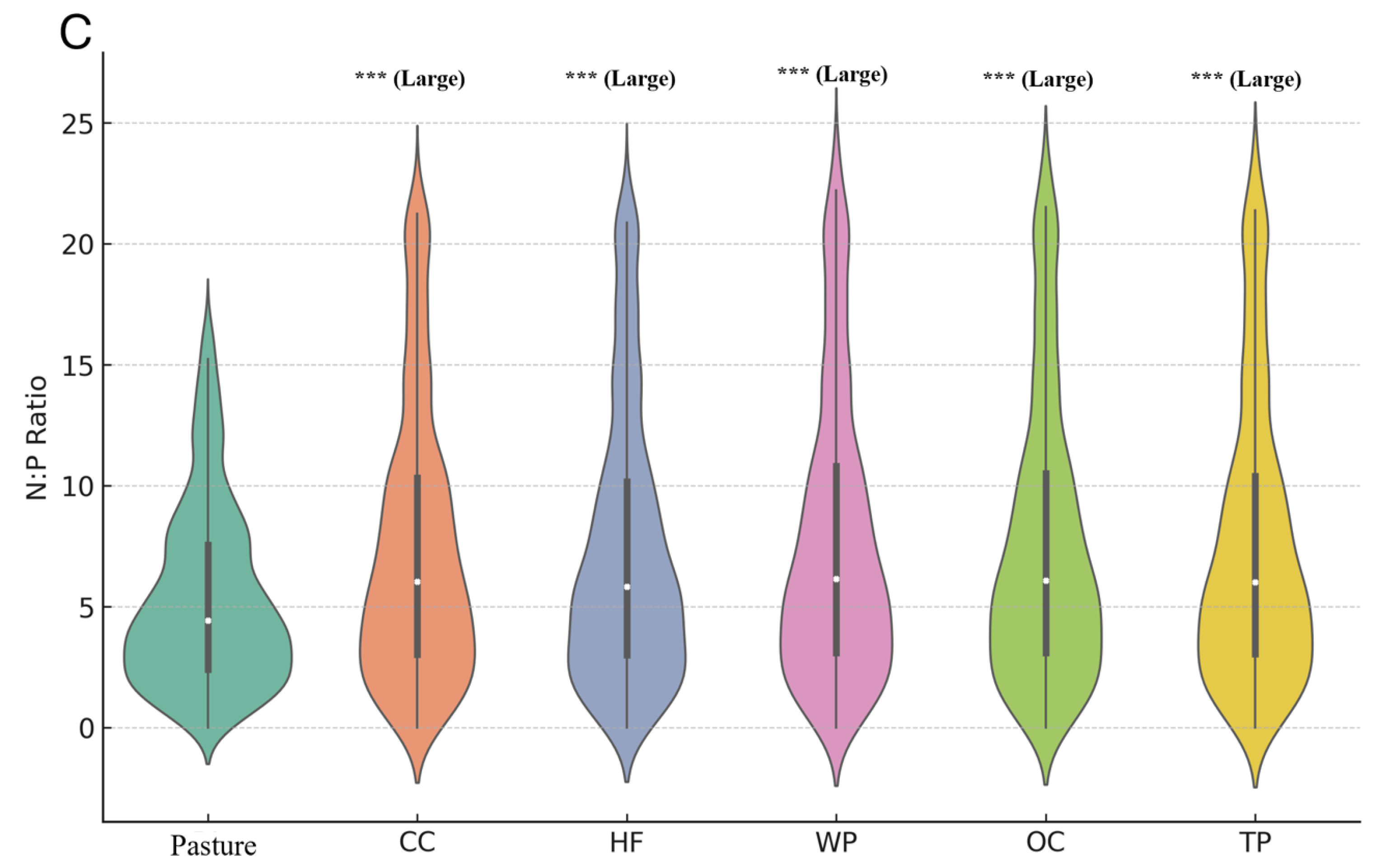

4.2. Implications of Elemental Ratios

4.3. Unidentified Spectral Features Classification

4.4. Implications and Advantages of Metabolomic Approaches in Soil Science

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reganold, J.P.; Wachter, J.M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliam, F.S.; Hargis, E.A.; Rabinowitz, S.K.; Davis, B.C.; Sweet, L.L.; Moss, J.A. Soil microbiomes of hardwood-versus pine-dominated stands: Linkage with overstory species. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pendall, E.; Malik, A.A.; Nannipieri, P.; Kim, P.J. Microbial control of soil organic matter dynamics: Effects of land use and climate change. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenovsky, R.E.; Vo, D.; Graham, K.J.; Scow, K.M. Soil Water Content and Organic Carbon Availability Are Major Determinants of Soil Microbial Community Composition. Microb. Ecol. 2004, 48, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauber, C.L.; Strickland, M.S.; Bradford, M.A.; Fierer, N. The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land-use types. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.D.; Jian, J.; Gyawali, A.J.; Thomason, W.E.; Badgley, B.D.; Reiter, M.S.; Strickland, M.S. What We Talk about When We Talk about Soil Health. Agric. Environ. Lett. 2018, 3, 180033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, E.; Hill, P.W.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Use of untargeted metabolomics for assessing soil quality and microbial function. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 143, 107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Li, S.; Hao, R.; Li, Q. Combined analysis of microbial community and microbial metabolites based on untargeted metabolomics during pig manure composting. Biodegradation 2021, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, T.; Wohlgemuth, G.; Lee, D.Y.; Lu, Y.; Palazoglu, M.; Shahbaz, S.; Fiehn, O. FiehnLib: Mass Spectral and Retention Index Libraries for Metabolomics Based on Quadrupole and Time-of-Flight Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 10038–10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viant, M.R. Recent developments in environmental metabolomics. Mol. Biosyst. 2008, 4, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Nguyen, C.; Finlay, R.D. Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: Carbon trading at the soil–root interface. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrilli, J.; Cooper, W.T.; Foreman, C.M.; Marshall, A.G. An ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry index to estimate natural organic matter lability. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 29, 2385–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, T.L.; Jenkins, S.; Bowen, B.P.; Northen, T.R. Untargeted soil metabolomics methods for analysis of extractable organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.A.H. Illuminating the dark metabolome to advance the molecular characterisation of biological systems. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautenhahn, R.; Cho, K.; Uritboonthai, W.; Zhu, Z.; Patti, G.J.; Siuzdak, G. An accelerated workflow for untargeted metabolomics using the METLIN database. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 826–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi Gyawali, A.; Strickland, M.S.; Thomason, W.; Reiter, M.; Stewart, R. Quantifying short-term responsiveness and consistency of soil health parameters in row crop systems. Part 1: Developing a multivariate approach. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 219, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.G.; Choudoir, M.; Fierer, N.; Strickland, M.S. Volatile organic compounds from leaf litter decomposition alter soil microbial communities and carbon dynamics. Ecology 2020, 101, e03130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, M.S.; Thomason, W.E.; Avera, B.; Franklin, J.; Minick, K.; Yamada, S.; Badgley, B.D. Short-Term Effects of Cover Crops on Soil Microbial Characteristics and Biogeochemical Processes across Actively Managed Farms. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2019, 2, 180064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; Kimball, E. Acidic Acetonitrile for Cellular Metabolome Extraction from Escherichia coli. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 6167–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBruyn, J.M.; Hoeland, K.M.; Taylor, L.S.; Stevens, J.D.; Moats, M.A.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Dearth, S.P.; Castro, H.F.; Hewitt, K.K.; Campagna, S.R.; et al. Comparative Decomposition of Humans and Pigs: Soil Biogeochemistry, Microbial Activity and Metabolomic Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 608856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.M.; Longnecker, K.; Kido Soule, M.C.; Arnold, W.A.; Bhatia, M.P.; Hallam, S.J.; Van Mooy, B.A.S.; Kujawinski, E.B. Metabolite composition of sinking particles differs from surface suspended particles across a latitudinal transect in the South Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.L.; Xie, Y.; Kara Murdoch, F.; Michalsen, M.M.; Löffler, F.E.; Campagna, S.R. Metabolome patterns identify active dechlorination in bioaugmentation consortium SDC-9™. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 981994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Su, X.; Klein, M.S.; Lewis, I.A.; Fiehn, O.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Metabolite Measurement: Pitfalls to Avoid and Practices to Follow. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, H. Integrated proteomics, metabolomics and physiological analyses for dissecting the toxic effects of halosulfuron-methyl on soybean seedlings (Glycine max merr.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 157, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Clasquin, M.F.; Melamud, E.; Amador-Noguez, D.; Caudy, A.A.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Metabolomic Analysis via Reversed-Phase Ion-Pairing Liquid Chromatography Coupled to a Stand Alone Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3212–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Dolios, G.; Petrick, L. Reproducible untargeted metabolomics workflow for exhaustive MS2 data acquisition of MS1 features. J. Cheminforma. 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiDonato, N.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Kew, W.; Sokol, N.W.; Clendinen, C.S.; Kyle, J.E.; Martínez, C.E.; Foley, M.M.; Tolić, N.; Pett-Ridge, J.; et al. Improved Characterization of Soil Organic Matter by Integrating FT-ICR MS, Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry, and Molecular Networking: A Case Study of Root Litter Decay under Drought Conditions. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 11699–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, J.; Schymanski, E.L.; Ahrens, L.; Alygizakis, N.; Béen, F.; Bijlsma, L.; Brunner, A.M.; Celma, A.; Fildier, A.; Fu, Q.; et al. NORMAN guidance on suspect and non-target screening in environmental monitoring. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, M.C.; Maclean, B.; Burke, R.; Amodei, D.; Ruderman, D.L.; Neumann, S.; Gatto, L.; Fischer, B.; Pratt, B.; Egertson, J.; et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamud, E.; Vastag, L.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Metabolomic Analysis and Visualization Engine for LC−MS Data. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 9818–9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasquin, M.F.; Melamud, E.; Rabinowitz, J.D. LC-MS Data Processing with MAVEN: A Metabolomic Analysis and Visualization Engine. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2012, 37, 14.11.11–14.11.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Kind, T.; Cajka, T.; Hazen, S.L.; Tang, W.H.W.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Irvin, M.R.; Arnett, D.K.; Barupal, D.K.; Fiehn, O. Systematic Error Removal Using Random Forest for Normalizing Large-Scale Untargeted Lipidomics Data. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 3590–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thonusin, C.; IglayReger, H.B.; Soni, T.; Rothberg, A.E.; Burant, C.F.; Evans, C.R. Evaluation of intensity drift correction strategies using MetaboDrift, a normalization tool for multi-batch metabolomics data. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1523, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Soufan, O.; Li, C.; Caraus, I.; Li, S.; Bourque, G.; Wishart, D.S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: Towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W486–W494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Psychogios, N.; Young, N.; Wishart, D.S. MetaboAnalyst: A web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (Suppl. S2), W652–W660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, S.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, F. NOREVA: Normalization and evaluation of MS-based metabolomics data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W162–W170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, J.; Yang, Q.; Cui, X.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, Q.; Xue, W.; Chen, N.; Zhu, F. Performance Evaluation and Online Realization of Data-driven Normalization Methods Used in LC/MS based Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChiPlot: UpSet Plot Tool. 2024. Available online: https://www.chiplot.online/upset_plot.html (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Kind, T.; Fiehn, O. Seven Golden Rules for heuristic filtering of molecular formulas obtained by accurate mass spectrometry. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttkies, C.; Schymanski, E.L.; Wolf, S.; Hollender, J.; Neumann, S. MetFrag relaunched: Incorporating strategies beyond in silico fragmentation. J. Cheminform. 2016, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit, t. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2025. Available online: https://posit.co/products/open-source/rstudio/?sid=1 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- (Zaner0445), G.u. Soil-Metabolomics-Elemental-Analysis. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Zaner0445/Soil-Metabolomics-Elemental-Analysis.git (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Python Software, F. Python 3.9. 2021. Available online: https://www.python.org/doc/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Zaner0445), G.u. Molecular-Formula-to-SMILES. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Zaner0445/Molecular-Formula-to-SMILES.git (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Kim, H.W.; Wang, M.; Leber, C.A.; Nothias, L.-F.; Reher, R.; Kang, K.B.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Gerwick, W.H.; Cottrell, G.W. NPClassifier: A Deep Neural Network-Based Structural Classification Tool for Natural Products. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis: Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Lesani, M.; Forrest, I.; Lan, Y.; Dean, D.A.; Gibaut, Q.M.R.; Guo, Y.; Hossain, E.; Olvera, M.; Panlilio, H.; et al. Local Phenomena Shape Backyard Soil Metabolite Composition. Metabolites 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific, Exactive Plus™ QuickStart Guide. Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. Available online: https://docs.thermofisher.com/v/u/Exactive-Plus-QuickStart-Guide (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Bajad, S.U.; Lu, W.; Kimball, E.H.; Yuan, J.; Peterson, C.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Separation and quantitation of water soluble cellular metabolites by hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1125, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Clemente, G.; García-González, M.A.; González-González, M. Soil lipid analysis by chromatography: A critical review of the current state in sample preparation. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, M.; Schoeny, H.; El Abiead, Y.; Hermann, G.; Rampler, E.; Koellensperger, G. Merging metabolomics and lipidomics into one analytical run. Analyst 2019, 144, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P.; Weintraub, M.N. The implications of exoenzyme activity on microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation in soil: A theoretical model. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, X. Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: Mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deangelis, K.M.; Sharma, D.; Varney, R.; Simmons, B.; Isern, N.G.; Markilllie, L.M.; Nicora, C.; Norbeck, A.D.; Taylor, R.C.; Aldrich, J.T.; et al. Evidence supporting dissimilatory and assimilatory lignin degradation in Enterobacter lignolyticus SCF1. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.L.; Dennis, P.G.; Owen, A.G.; van Hees, P.A.W. Organic acid behavior in soils—Misconceptions and knowledge gaps. Plant Soil 2003, 248, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel-Knabner, I. The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Louie, K.B.; Hao, Z.; Mansoori, N.; da Rocha, U.N.; Shi, S.; Cho, H.; Karaoz, U.; Loqué, D.; Bowen, B.P.; et al. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.G.; Bardgett, R.D.; van Straalen, N.M. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Schimel, J.P. Effects of drying–rewetting frequency on soil carbon and nitrogen transformations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Lauber, C.L.; Weintraub, M.N.; Ahmed, B.; Allison, S.D.; Crenshaw, C.; Contosta, A.R.; Cusack, D.; Frey, S.; Gallo, M.E.; et al. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, C.C.; Liptzin, D. C:N:P stoichiometry in soil: Is there a “Redfield ratio” for the microbial biomass? Biogeochemistry 2007, 85, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Keiblinger, K.M.; Mooshammer, M.; Peñuelas, J.; Richter, A.; Sardans, J.; Wanek, W. The application of ecological stoichiometry to plant–microbial–soil organic matter transformations. Ecol. Monogr. 2015, 85, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Haygarth, P.M. Biogeochemistry. Phosphorus solubilization in rewetted soils. Nature 2001, 411, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, B.; Chodak, M.; Jaźwa, M.; Solak, A.; Tarasek, A.; Niklińska, M. The relationship between soil bacteria substrate utilisation patterns and the vegetation structure in temperate forests. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P.; Schaeffer, S.M. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrold, D.D.; Zeglin, L.H.; Jansson, J.K. The Potential of Metagenomic Approaches for Understanding Soil Microbial Processes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenbach, C.M.; Frey, S.D.; Grandy, A.S. Direct evidence for microbial-derived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.F.; Strack, D.; Wink, M. Biosynthesis of Alkaloids and Betalains. In Annual Plant Reviews Volume 40: Biochemistry of Plant Secondary Metabolism; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 20–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zelles, L. Fatty acid patterns of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides in the characterisation of microbial communities in soil: A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1999, 29, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunina, A.; Dippold, M.; Glaser, B.; Kuzyakov, Y. Turnover of microbial groups and cell components in soil: 13C analysis of cellular biomarkers. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha; Bhardwaj, Y.; Sharma, M.P.; Pandey, J.; Dubey, S.K. Response of Crop Types and Farming Practices on Soil Microbial Biomass and Community Structure in Tropical Agroecosystem by Lipid Biomarkers. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1618–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, D.A.; Scow, K.M. Impacts of Carbon and Flooding on Soil Microbial Communities: Phospholipid Fatty Acid Profiles and Substrate Utilization Patterns. Microb. Ecol. 1998, 35, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Dannert, H.; Griffiths, R.I.; Thomson, B.C.; Gleixner, G. Rhizosphere bacterial carbon turnover is higher in nucleic acids than membrane lipids: Implications for understanding soil carbon cycling. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Jackson, R.D.; DeLucia, E.H.; Tiedje, J.M.; Liang, C. The soil microbial carbon pump: From conceptual insights to empirical assessments. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6032–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.Y.; Scow, K.M.; Córdova-Kreylos, A.L.; Holmes, W.E.; Six, J. Microbial community composition and carbon cycling within soil microenvironments of conventional, low-input, and organic cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wipf, H.M.; Xu, L.; Gao, C.; Spinner, H.B.; Taylor, J.; Lemaux, P.; Mitchell, J.; Coleman-Derr, D. Agricultural Soil Management Practices Differentially Shape the Bacterial and Fungal Microbiome of Sorghum bicolor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02345-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wittwer, R.A.; Banerjee, S.; Walser, J.-C.; Schlaeppi, K. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperschütz, J.; Gattinger, A.; Mäder, P.; Schloter, M.; Fliessbach, A. Response of soil microbial biomass and community structures to conventional and organic farming systems under identical crop rotations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 61, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.E. Litter decomposition: What controls it and how can we alter it to sequester more carbon in forest soils? Biogeochemistry 2010, 101, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Yang, F.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, X. Alterations in soil microbial community composition and biomass following agricultural land use change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladó, S.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Baldrian, P. Forest Soil Bacteria: Diversity, Involvement in Ecosystem Processes, and Response to Global Change. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieland, M.A.; Lacy, P.; Allison, S.D.; Bhatnagar, J.M.; Doroski, D.A.; Frey, S.D.; Greaney, K.; Hobbie, S.E.; Kuebbing, S.E.; Lewis, D.B.; et al. Nitrogen Deposition Weakens Soil Carbon Control of Nitrogen Dynamics Across the Contiguous United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vickery, Z.A.; Castro, H.F.; Dearth, S.P.; Tague, E.D.; Classen, A.T.; Moore, J.A.; Strickland, M.S.; Campagna, S.R. Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Soil Metabolic Profiles Across Land Management Practices. Metabolites 2025, 15, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120783

Vickery ZA, Castro HF, Dearth SP, Tague ED, Classen AT, Moore JA, Strickland MS, Campagna SR. Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Soil Metabolic Profiles Across Land Management Practices. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120783

Chicago/Turabian StyleVickery, Zane A., Hector F. Castro, Stephen P. Dearth, Eric D. Tague, Aimée T. Classen, Jessica A. Moore, Michael S. Strickland, and Shawn R. Campagna. 2025. "Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Soil Metabolic Profiles Across Land Management Practices" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120783

APA StyleVickery, Z. A., Castro, H. F., Dearth, S. P., Tague, E. D., Classen, A. T., Moore, J. A., Strickland, M. S., & Campagna, S. R. (2025). Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Soil Metabolic Profiles Across Land Management Practices. Metabolites, 15(12), 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120783