1. Introduction

Drugs that regulate hydrochloric acid synthesis—secreted by the gastric glands via parietal cells—are classified under ATC code A02B. The most used drugs within this category are those for treating reflux and ulcers, with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs, A02BC) being particularly prominent. Among PPIs, omeprazole (A02BC01) is the leading active ingredient [

1,

2].

Omeprazole is primarily indicated for the treatment and prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric or duodenal ulcers, reflux esophagitis, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, and

Helicobacter pylori infection [

3]. This drug is also eligible for inclusion in professional pharmaceutical care services for dispensing, provided there is a medical prescription, a pharmacist’s recommendation, and pharmacotherapeutic monitoring.

Data from OECD member countries on PPI consumption indicate a steady increase in the defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants per day. Notably, Spain recorded the highest DDD among OECD countries from 2015 to 2021, reaching a peak of 134.9 DDDs in 2021, followed by countries such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In contrast, Slovakia and Austria have DDDs in 2021 of 50.8 and 29.8, respectively [

4].

In 2021, the average consumption of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in Spain, measured in defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants (DHD), reached 88.9—exceeding the European average by 51.7% [

4].

Recent data from the Medicines Use Observatory of the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) (19 October 2023) indicate a notable rise in omeprazole consumption and other PPIs in Spain, particularly from the 2010s onward and accelerating post-COVID-19 pandemic [

2]. National prescribing trends for PPIs reveal a continuous upward trajectory, peaking at 134.79 DHD in the fourth quarter of 2021 and stabilizing at 134.51 DHD throughout 2022. Specifically, omeprazole (ATC group A02BC) shows a similar growth pattern, with a consumption trend that appears challenging to justify on therapeutic grounds alone. In 2022, omeprazole represented 76.14% of all PPI sales in Spain, based on AEMPS data [

2].

Several countries have implemented monitoring and deprescribing guidelines for omeprazole in response to rising PPI consumption. Examples include France (2022) [

5], Canada with deprescribing guidelines introduced in 2017 [

6], the United States through the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) in 2022 [

7], and Australia in 2019 [

8].

The concomitant use of omeprazole with drugs such as antiretrovirals, digoxin, clopidogrel, warfarin, diazepam, and phenytoin are associated with drug–drug interactions, potentially leading to adverse outcomes [

3,

9,

10]. Additionally, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued warnings that PPIs may be linked to acute interstitial nephritis [

11] and vitamin B12 deficiency when used chronically (over two years) [

12,

13].

Extensive clinical experience confirms the high therapeutic efficacy of PPIs, primarily due to their potent acid-inhibitory effect. However, the substantial and largely unwarranted demand, coupled with the widespread availability of omeprazole outside of hospital settings, underlined the need for this study. We aimed to establish a foundation for designing and implementing professional pharmaceutical care services for dispensing and pharmaceutical guidance regarding omeprazole use.

We consider drug dispensing a critical control point for ensuring the safe and appropriate use of omeprazole. Therefore, this study emphasizes the role of pharmaceutical care (PC) and community pharmacies as healthcare and research hubs dedicated to promoting rational drug use. Through monitoring parameters such as usage appropriateness, dosage, adherence, interactions, and contraindications, we aim to support patient safety and minimize risks associated with omeprazole.

2. Material and Methods

We conducted an observational, descriptive, single-center, cross-sectional study involving 100 patients using omeprazole at a community pharmacy in Barcelona. The study period spanned from 1 November 2023 to 31 May 2024, and was situated within the framework of the Pharmaceutical Care Service for medication dispensing and guidance.

The study protocol received approval from the Medicines Research Ethics Committee (CEIm) of the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias (HUC), under code FCF-OME-2023-1. All procedures adhered to current ethical and legal regulations concerning patient rights and safety.

The methodology included a single clinical interview, averaging 12 min in duration, conducted within the pharmacy’s Personalized Care Zone. Patients received a Patient Information Sheet and provided informed consent before data collection. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire, and upon completion of the consultation, patients were given an informational leaflet on omeprazole’s appropriate use, along with lifestyle recommendations aligned with Pharmaceutical Care objectives (

Figure A1).

The questionnaire was organized into several sections; this article focuses on sociodemographic variables (sex and age) and pharmacotherapeutic data (number of medications, duration of omeprazole use, prescribing physician, source of prescription, presence of stomach pain, and dosing regimen). Additionally, therapeutic adherence was assessed using the Morisky–Green test (

Table 1), and the STOPP criteria were applied to identify potential Medication Related Problems (MRPs).

It is important to note that the study was limited by the lack of comprehensive access to participants’ medical records through the Spanish Community Pharmacy Network. This constraint restricted the depth of analysis of certain aspects of the clinical history, diagnoses, and prescribed treatments.

The variables assessed in this study were carefully selected to comprehensively characterize the omeprazole user profile and therapeutic behavior and identify potential areas for pharmaceutical intervention. These variables are as follows:

Sex: Patients were categorized as male or female, enabling analysis of potential differences in omeprazole use by sex, which may inform tailored pharmaceutical care strategies.

Age: Patients were classified into five age groups (18–25 years, 26–40 years, 41–50 years, 51–65 years, and over 65 years). This categorization enables the observation of omeprazole usage patterns by age, helping identify age groups that may be more susceptible to prolonged or inappropriate use.

Number of Medications: We recorded whether patients were on monotherapy or polytherapy (defined as the use of five or more concurrent medications). This variable is critical for identifying potential drug–drug interactions and risks associated with polypharmacy, particularly relevant among chronic and elderly patients.

Duration of Omeprazole Use: The duration of omeprazole use was categorized into five timeframes: less than 6 months, 6 months to 2 years, 2 to 6 years, 6 to 10 years, and over 10 years. This variable is essential for identifying prolonged use, which may be linked to long-term adverse effects, such as renal and bone complications.

Risk Perception: Patients’ subjective perception of the risks associated with omeprazole use was assessed. This included whether patients consider the medication safe or are aware of potential adverse effects, as these perceptions may influence their adherence to treatment and their willingness to accept changes in therapy.

Origin of Omeprazole: We distinguished between patients obtaining omeprazole through over-the-counter means and those receiving it via prescription. Within the latter group, we categorized prescriptions based on whether they were issued by a specialist or a primary care physician. This variable offers insights into the different access routes to the medication and the control surrounding its prescription.

Prescribing Institution: We identified the source of the prescription, categorizing it as coming from a private center, a public mutual insurance company, or a public prescription issued by regional health authorities.

Pre-Treatment Stomach Pain: We recorded whether patients experienced stomach pain prior to initiating treatment with omeprazole. This information may provide insights into potential overuse of the drug in cases where its indication is not clearly warranted.

Dosing Regimen: The administration regimen of omeprazole was analyzed concerning frequency and dosage to evaluate treatment adequacy following established guidelines.

Defined Daily Dose (DDD): According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the DDD for omeprazole is set at 20 mg/day. This study assessed whether patients exceeded this recommended dose, allowing for the identification of potential overdosage situations and their associated risks.

Therapeutic Adherence: Often referred to as medication adherence, it refers to the extent to which a patient follows the prescribed treatment regimen as intended by the healthcare provider. Adherence is crucial for ensuring the effectiveness of the treatment, preventing disease progression, and minimizing the risk of adverse outcomes. Poor adherence can lead to treatment failure, complications, and increased healthcare costs. The validated Morisky–Green test [

14] was employed to measure adherence in the 78 patients that were detected to use omeprazole daily and chronically since it was not considered to be relevant in the 22 patients that reported using omeprazole occasionally, following an on-demand, short-term treatment. Patients were classified as adherent if their responses to the four questions were NO, YES, NO, NO, NO (

Table 1).

After administering the questionnaire, the community pharmacists analyzed the results to detect medication-related problems (MRPs) and negative medication outcomes. The identification of MRPs was conducted following the 2024 Practice Guide for Pharmaceutical Care Services developed by the Pharmaceutical Care Forum of the General Council of Official Associations of Pharmacists of Spain (Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos de España) [

15].

Subsequently, the presence or absence of STOPP (

Screening Tool of Older Persons Potentially) criteria was evaluated to determine the justification for omeprazole use. The STOPP criteria, as established by Gallagher et al. (2008) [

16], were employed in this assessment. As indicated by the acronym, the STOPP criteria are designed to facilitate the discontinuation of treatments based on established clinical evidence. These criteria were developed using a Delphi consensus technique and organized by physiological systems for patients over 65. The STOPP criteria relevant to omeprazole use include the following:

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease or erosive peptic esophagitis at full therapeutic doses for more than 8 weeks.

Medications prescribed or indicated without an evidence-based rationale.

Pharmaceutical intervention (PI) encompasses several key actions aimed at optimizing medication use. These actions include providing personalized medicine information, health education, pharmacotherapeutic monitoring, and referral to a physician when medication-related problems (MRPs) or negative medication reactions are identified. Additionally, pharmacists may propose deprescribing or suggest other modifications to treatment in coordination with the prescribing physician. Reporting adverse reactions to the pharmacovigilance service is also an integral part of this process, in compliance with current legislation. Documentation of communication with the physician—whether in writing—and whether the PI was accepted by the patient and implemented by the physician is also maintained.

For data analysis, descriptive statistical techniques and graphical visualizations were employed using R software (version 4.4.0,

www.r-project.org, accessed on 10 January 2025). Discrete variables were represented using bar and pie charts, while continuous variables were analyzed using histograms. Furthermore, measures of central tendency and proportions were calculated to effectively describe the distribution of the responses obtained across various qualitative variables.

3. Results

The results of the study indicate a balanced sex distribution among participants, with 51% identifying as female and 49% as male. The age distribution, categorized into five groups, is as follows: 18–25 years (1%), 26–40 years (5%), 41–50 years (13%), 51–65 years (25%), and over 65 years (56%). Notably, 81% of the participants are over the age of 51, highlighting that omeprazole use is more prevalent in this demographic. This observation confirms our hypothesis that older adults represent an ideal target population for pharmaceutical intervention.

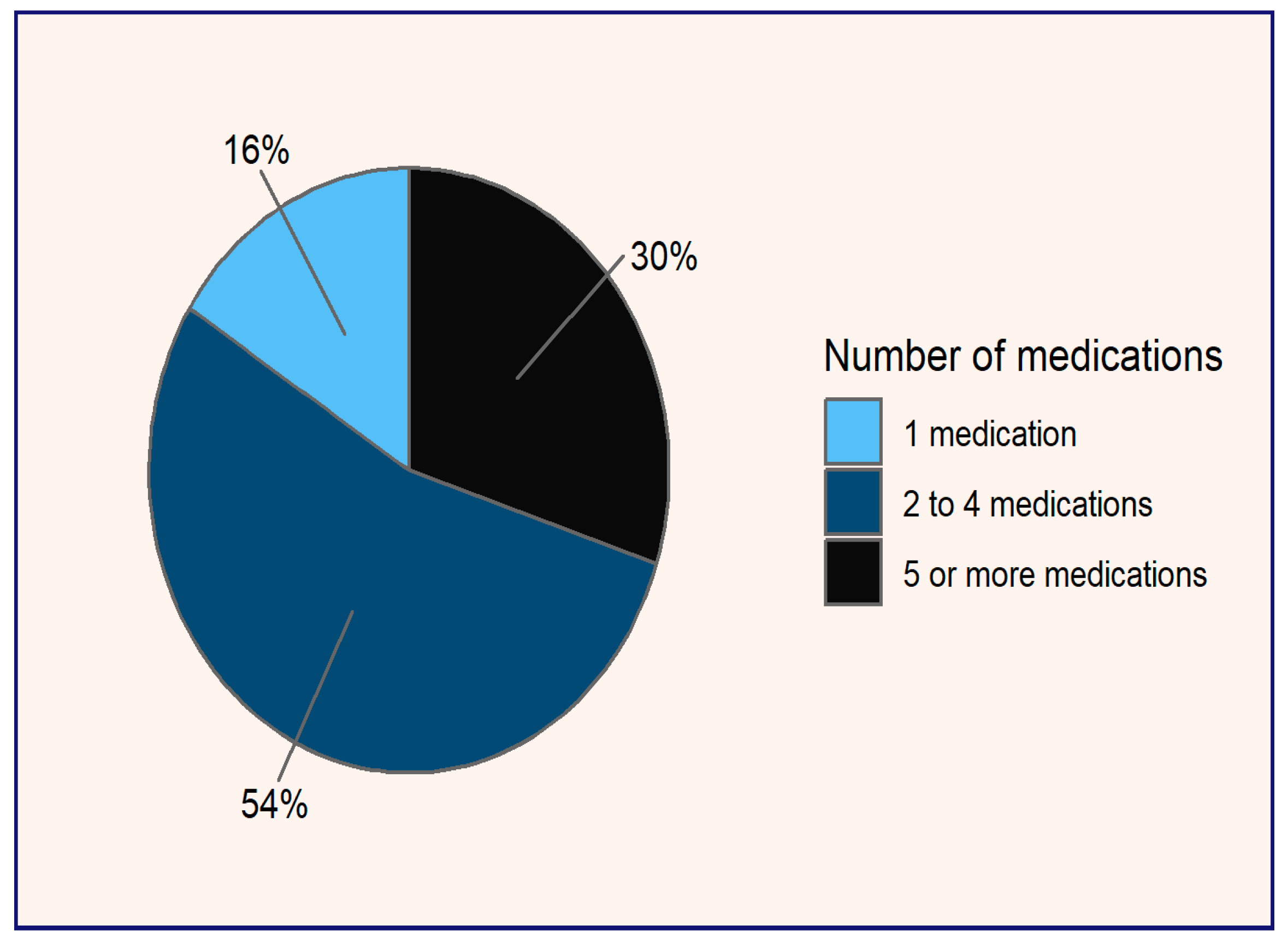

In terms of pharmacotherapy (see

Figure 1), it is observed that 30% of patients are polymedicated, defined as those taking five or more medications, while 54% are on a regimen of two to four drugs. Only 16% of participants use omeprazole as monotherapy. The prevalence of polymedication poses risks of negative outcomes associated with medication due to potential drug interactions. Furthermore, the simultaneous use of multiple medications can complicate adherence, as patients may struggle to keep track of doses and schedules, increasing the likelihood of errors and serious side effects [

17].

In addition, the analysis revealed that 71% of the patients were on chronic omeprazole therapy, defined as treatment lasting more than two years. This chronic usage can be further categorized as follows: 36% of patients had been on omeprazole for over 10 years, 15% for a duration of 6 to 10 years, and 20% for more than two years (see

Figure 2). Notably, within this cohort of chronic users, a concerning 94% reported not perceiving any associated risks related to the long-term use of omeprazole.

These findings highlight the prevalence of prolonged omeprazole therapy among the patient population and suggest a critical need for enhanced patient education regarding the potential long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. The lack of risk awareness among most chronic users underscores the importance of regular pharmacotherapeutic evaluations and the implementation of appropriate pharmaceutical interventions to mitigate potential adverse outcomes associated with extended use.

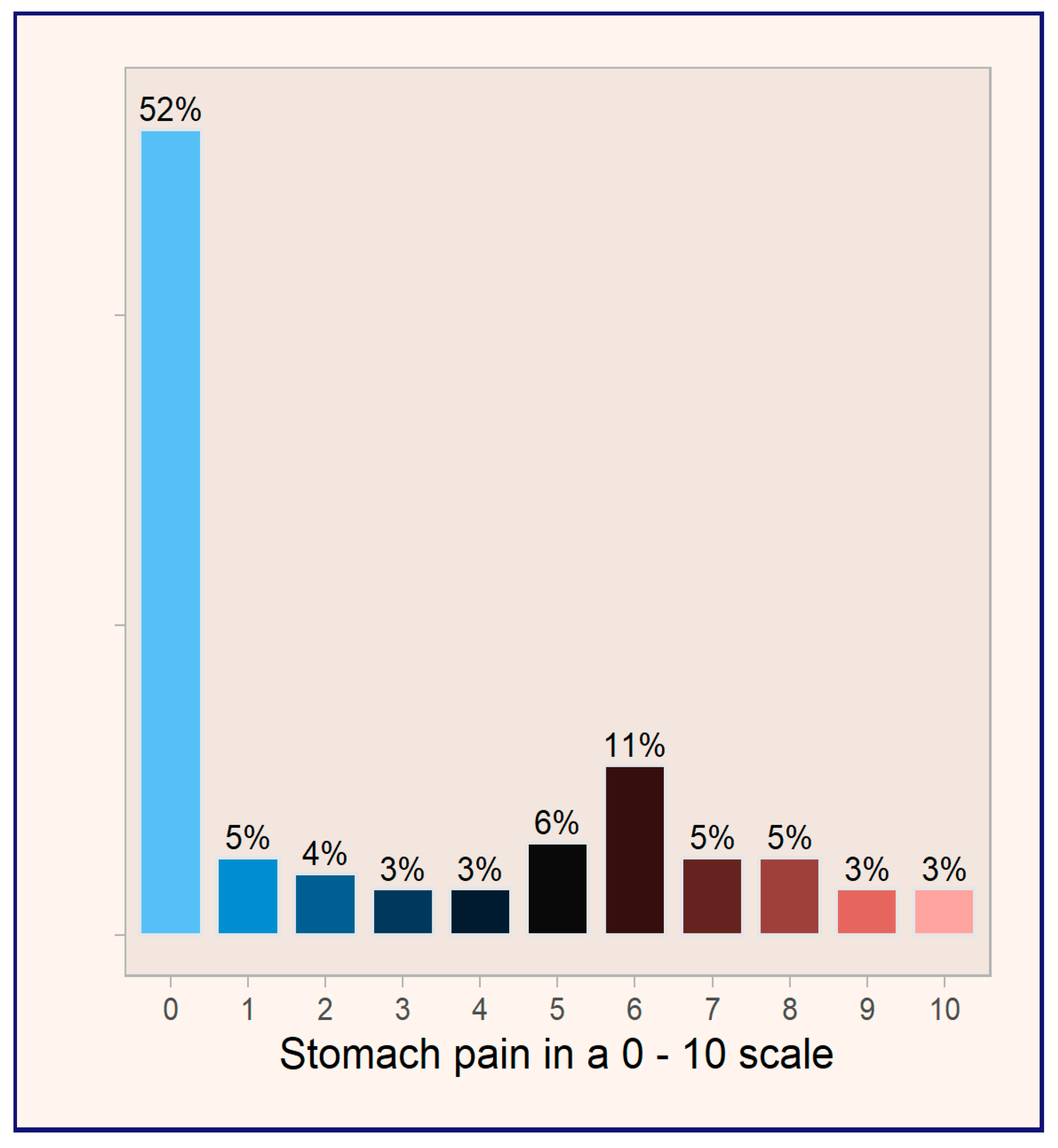

A noteworthy finding from the study is that 52% of patients reported experiencing no stomach pain before initiating treatment with omeprazole (see

Figure 3). This observation raises important questions regarding the appropriateness of omeprazole prescriptions in this patient population, suggesting a potential trend of over-prescribing in the absence of clearly indicated symptoms. It emphasizes the need for careful assessment of treatment indications and the importance of evaluating the necessity of proton pump inhibitors in patients without documented gastrointestinal complaints.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) of omeprazole as 20 mg, based on its optimal therapeutic efficacy and safety profile for most patients. This standard aims to ensure an appropriate balance between the benefits and risks of treatment. However, our study findings reveal that 13% of patients exceed this recommended dose, utilizing omeprazole at 40 mg daily, effectively doubling the DDD.

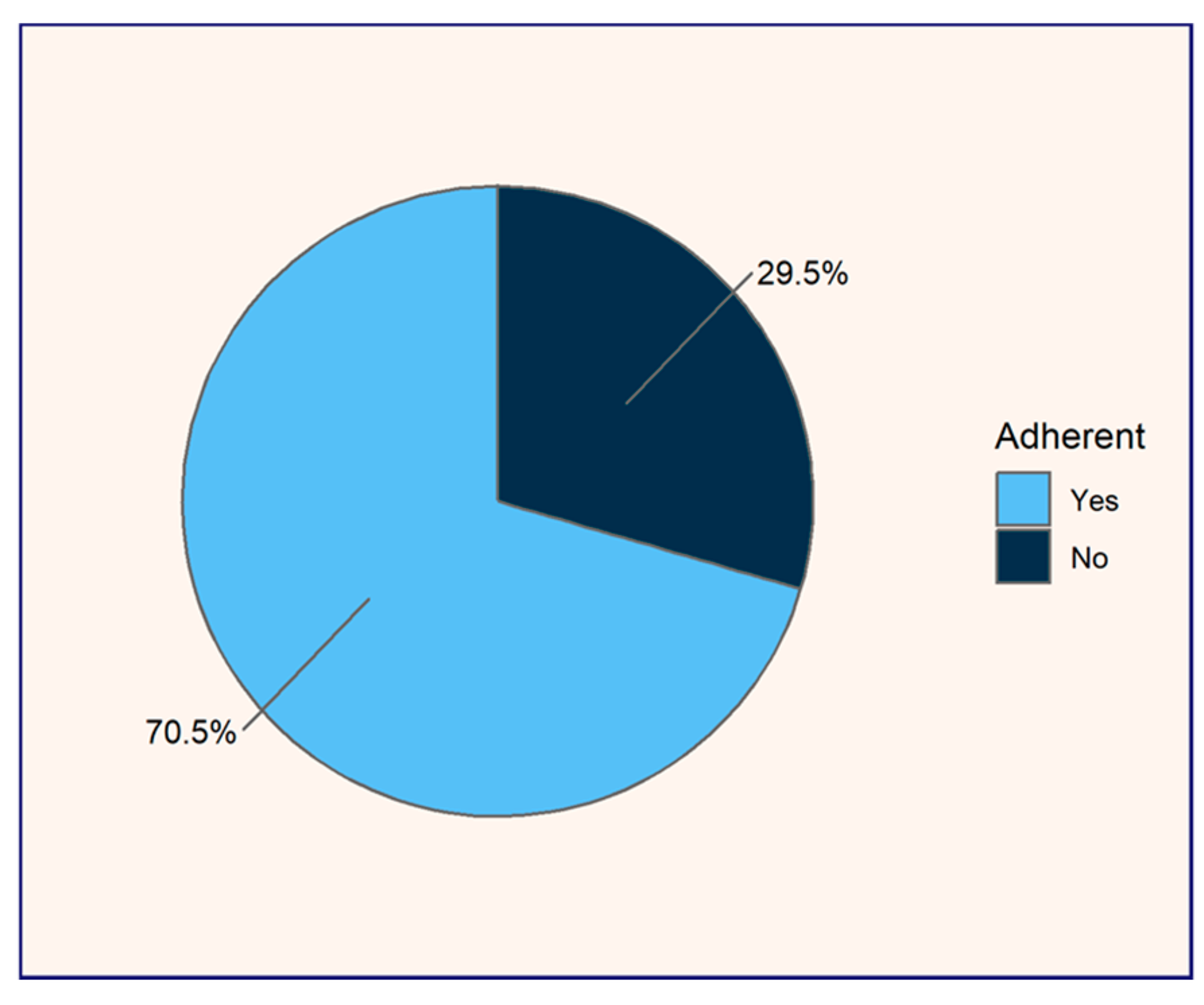

Of the 100 patients studied, 22% (n = 22) reported using omeprazole occasionally, following an on-demand, short-term treatment prescribed by their physician, while 78% (n = 78) adhered to a chronic daily dosing regimen. Given that adherence to medication regimens is essential for ensuring therapeutic efficacy and minimizing the risks associated with pharmacotherapy, the Morisky–Green test was applied to evaluate adherence among these 78 chronic daily omeprazole users. Adherence within this group was found to be 70.51%, while non-adherence accounted for 29.5% (see

Figure 4).

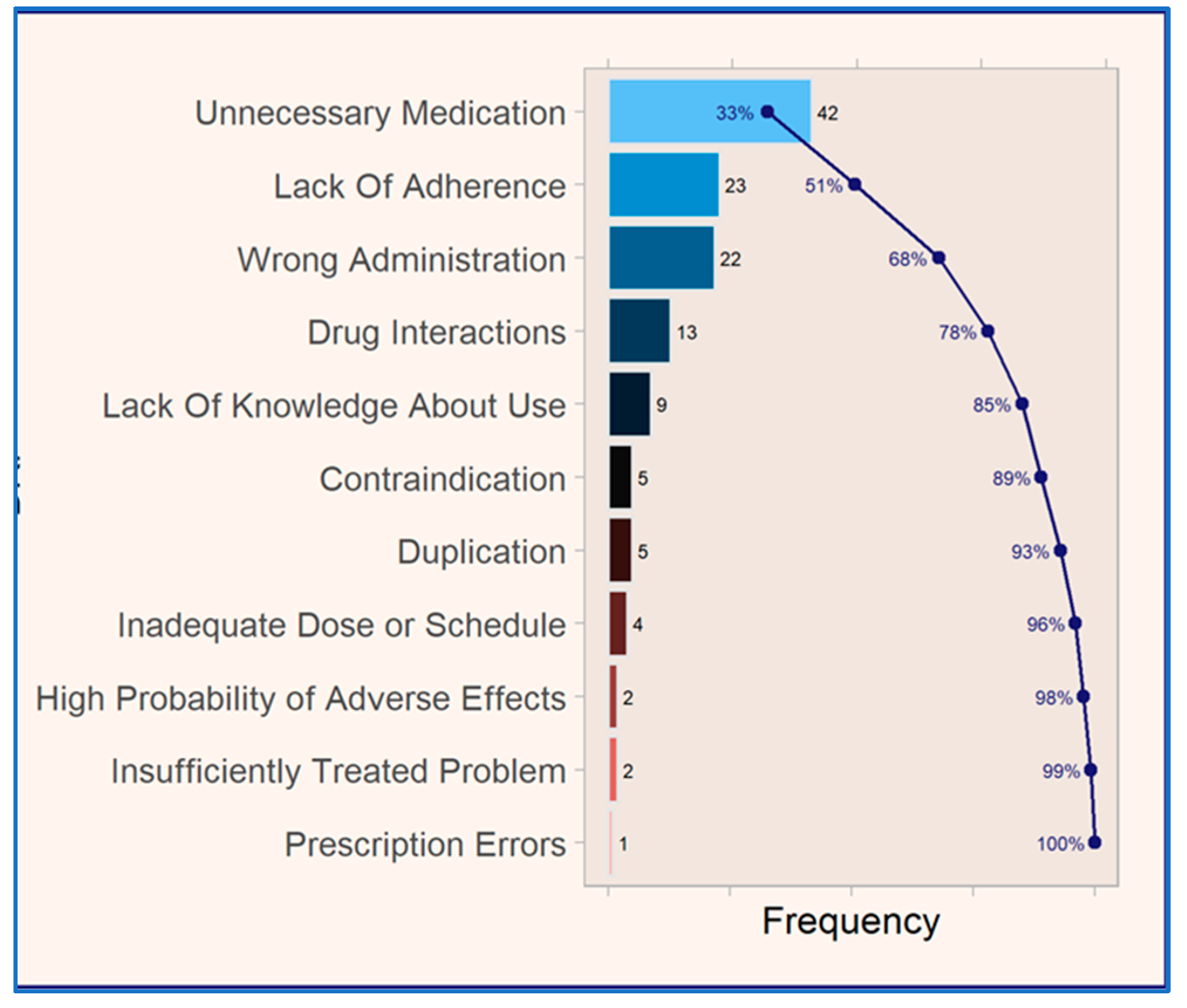

The analysis of medication-related problems (MRPs) (see

Figure 5) among the 78 patients using omeprazole daily and chronically revealed that the most prevalent MRP was classified as “unnecessary medication,” accounting for 33% of all documented MRPs. This was followed by MRPs classified as “lack of adherence”, “wrong administration”, “drug interactions”, and “lack of knowledge regarding medication use”, among others. Together, these five MRP categories represented 85% of the total MRPs identified, underscoring their significant contribution to the overall MRP burden in the study.

According to the STOPP criteria, 8% are taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for ulcerative disease or erosive peptic oesophagitis at therapeutic doses for more than eight weeks, indicating a need for dose adjustment or deprescribing. Furthermore, concerning the second criterion of the STOPP guidelines, 37% of patients are prescribed omeprazole without an evidence-based indication. Notably, among patients aged over 65 years, 57% warrant dose adjustment or deprescribing of omeprazole, as will be further discussed.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that 13% of the evaluated patients exceeded the World Health Organization Defined Daily Dose (DDD) of 20 mg/day of omeprazole, raising concerns regarding the risk of overdose and associated adverse effects. Previous studies have used the comparison between the Prescribed Daily Dose (PDD) and the DDD as an indicator of therapeutic uncertainty [

17]. Given that 30% of omeprazole users are polymedicated (defined as those receiving five or more medications), it is crucial to design pharmaceutical interventions specifically targeting this group, which is particularly susceptible to drug–drug interactions. This underscores the need to optimize their treatment, as recommended by Delgado et al. (2009) [

17].

Chronic omeprazole treatment is a common practice, as reflected in the first STOPP criterion, which states that extending treatment beyond the recommended 8 weeks for peptic ulcer disease, reflux esophagitis, or gastroesophageal reflux disease increases the risk of drug interactions and adverse effects [

18]. Despite these risks, 92% of the interviewed patients did not associate chronic omeprazole use with health risks, indicating a lack of awareness regarding potential long-term adverse effects. Research on chronic drug use and patients’ lack of knowledge indicates that insecurity associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines correlates with patients’ ignorance about their treatment [

19].

The finding that 71% of patients have been using omeprazole for more than 2 years exposes these users to an increased risk of long-term side effects, such as kidney damage, bone fractures, osteoarthritis, impaired sexual development, iron deficiency, and megaloblastic anemia, as well as a potential risk of cancer [

11,

13,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The study by Mir (2023) shows that treatment adherence varies according to patient’s knowledge of their pharmacotherapy [

27]. In our study, 29.5% of daily chronic omeprazole patients exhibited a lack of adherence to omeprazole treatment, suggesting insufficient commitment to their regimen, often in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, leaving them asymptomatic.

The adherence patterns highlight variations in patient behavior and perceptions of treatment necessity. For patients on chronic daily regimens, the high adherence rate (70.5%) may be influenced by their recognition of the long-term severity of their condition and the perceived importance of ongoing treatment. Additionally, medical follow-up likely plays a crucial role in these patients with chronic conditions, as they often participate in regular consultations with healthcare providers, which reinforces adherence through continuous professional guidance. Although an adherence rate of 70.5% to omeprazole could be considered optimal, we are concerned about the 29.5% of chronic daily omeprazole users who are non-adherent. These patients require further health education and a stronger commitment to treatment to avoid therapeutic failure. It is also essential to differentiate between adherence and compliance to more effectively engage patients in positive health outcomes. Mir (2023) advocates for adherence by promoting patient autonomy and fostering behavioral change, whereas compliance imposes treatment without attempting to alter patient behavior, relying solely on passive conformity to health recommendations [

27].

The finding that 57% of patients over the age of 65 met STOPP criteria [

16] suggests a high potential prevalence of over-prescription, highlighting the need to analyze the indications for which omeprazole has been prescribed, given that 37% of cases were prescribed without medical evidence. Data provided by Gutiérrez-Igual et al. (2024) [

20] align with our study by identifying a high prevalence of medication-related problems (MRPs), with at least one case present in 97.3% of patients and 46.9% of omeprazole-related interactions. Patients older than 54 years, particularly women taking more than 13 medications, are at a higher risk of developing MRPs. The most frequent interactions are usually mild; however, identifying these risk factors allows for optimized monitoring and improved efficient use of healthcare resources [

19].

Implementing multidisciplinary strategies through physician–pharmacist interactions is crucial to reduce unnecessary medications. Farrell et al. (2017), in their evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for deprescribing proton pump inhibitors in Canada, report that deprescribing PPIs is safe and effective in reducing polypharmacy [

6]. These authors provide evidence-based practice guidelines for reducing the dose or discontinuing the use of PPIs.

At the national level, publications by Carranza (2015) highlight that 60% of patients exceed the recommended treatment duration with omeprazole, and 4.5% of the elderly take it at high doses for more than a year, increasing their risk of adverse reactions. Furthermore, more than half of the patients do not remember the prescribed duration of treatment [

21]. Frígola (2008) concluded that the use of omeprazole in community pharmacies on the Girona coast reveals that a high percentage of patients exceed the recommended treatment duration, thereby increasing the risk of adverse effects [

28].

Pharmaceutical intervention is essential to ensure safe and effective medication use. Internationally, studies such as those by Schepisi et al. (2016) [

23] demonstrate that the use of omeprazole is not always therapeutically justified. Farrell et al. (2017) provide practical recommendations for making decisions regarding when and how to reduce dosage or discontinue PPIs, suggesting that deprescribing PPIs is a recommended practice [

6]. Additionally, Curtain et al. (2011) detail a protocol for deprescribing omeprazole in England through electronic notices in community pharmacies [

24], and Alshammari (2019) highlights the irrational prescribing of this molecule in Saudi Arabia [

25].

Given that 52% of patients reported no stomach pain before omeprazole treatment, it can be assumed that a significant proportion of its use may not be justified, as conditions such as heartburn, gastric and peptic ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, and

H. pylori infection are typically associated with abdominal and/or chest pain [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This may suggest the unnecessary administration of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), warranting an assessment of necessity and potential referral to a physician. de Velasco et al. (2022) found that after sending letters to patients using omeprazole, physicians deprescribed treatment in 52.6% of cases, discontinued treatment in 20%, and reduced the dosage in 32.6% of cases [

31].

This empirical study aligns with Pareto’s principle, or the 80/20 rule, as 20% of the described MRPs account for 80% of the detected MRPs, demonstrating the consistency of the analysis and the reliability of the sample [

32].

5. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

- -

Limitations: The study’s sample size, while adequate to ensure statistical significance, may not be representative enough to generalize the findings to larger populations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to assess temporal trends in omeprazole usage or changes in clinical practices. Additionally, the absence of access to medical records restricted the evaluation of Medication-Related Problems (MRPs) and treatment appropriateness to patient-reported data, potentially introducing recall and reporting biases. Finally, the study’s exclusive focus on omeprazole precluded comparisons with other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), narrowing the scope and leaving opportunities for future research.

- -

Strengths: This study leverages real-world clinical data, enhancing its external validity and practical relevance. By identifying prescribing, administration, and adherence patterns, it provides actionable insights for improving pharmacy practice and patient safety. The use of validated tools, such as the AF-FC Forum criteria for MRP classification, ensures a robust and standardized methodology. Furthermore, the study addresses key issues like deprescribing and the risks of prolonged omeprazole use, contributing valuable evidence for educational initiatives and healthcare policy development.

6. Conclusions

The excessive consumption of omeprazole raises significant concerns regarding the risks associated with its potentially inappropriate use. The role of the community pharmacist is crucial in ensuring the safety of polymedicated and chronic patients. Their responsibilities in medication review, interaction detection, and health education are essential for preventing adverse effects and optimizing treatment, underscoring their importance as key healthcare professionals.

The incorporation of STOPP criteria and validated assessments, alongside an understanding of the patient profile utilizing omeprazole within the PC service protocols, equips community pharmacists to identify patient needs effectively. This approach facilitates tailored pharmaceutical interventions that align with individualized patient care.

The detection of potential proton pump inhibitor overuse and medication-related problems within community pharmacy settings promotes collaborative practice with other healthcare professionals. This collaboration encourages referrals to physicians for deprescribing, which represents an ideal pharmaceutical intervention that would minimize the potential negative outcomes associated with omeprazole.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.F., D.A.A., A.M.M. and C.R.A.; methodology, F.C.F., D.A.A., V.H.G. and C.R.A.; software, F.C.F. and Y.S.A.; formal analysis, F.C.F. and D.A.A.; investigation, F.C.F., D.A.A., V.H.G. and C.R.A.; resources, F.C.F., A.H.d.l.T. and D.A.A.; data curation, Y.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.F., D.A.A. and C.R.A.; writing—review and editing, F.C.F., D.A.A. and C.R.A.; supervision, C.R.A.; funding acquisition, F.C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for the data analysis of the study was provided by the Community Pharmacy “Finestres Capdevila” in Barcelona.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work includes partial results from the observational study (sponsor protocol FCF-OME-2023-01 version 2) titled "Pharmaceutical Care for the Optimization of the Safety and Rational Use of Omeprazole in Dispensing and Pharmaceutical Indication Services in Community Pharmacy", which was favorably evaluated for execution by the Research Ethics Committee for Medicines of the Canary Islands University Complex in its extraordinary meeting on 16/11/2023 (minutes 12/2023). (Spanish version: Este trabajo incluye resultados parciales del estudio observacional (protocolo del promotor FCF-OME-2023-01 versión 2) titulado "Atención Farmacéutica para la optimización de la seguridad y uso racional de Omeprazol en los servicios de dispensación e indicación farmacéutica en Farmacia Comunitaria", que fue evaluado favorablemente para su ejecución por el Comité de Ética de la Investigación con Medicamentos del Complejo Universitario de Canarias en su reunión extraordinaria de 16/11/2023 (acta 12/2023)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

English version of the Leaflet explaining Omeprazole.

Figure A1.

English version of the Leaflet explaining Omeprazole.

References

- ATCDDD—Home [Internet]. Available online: https://atcddd.fhi.no/ (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- AEMPS. Observatorio de Uso de Medicamentos. 2021. Available online: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/observatorio-de-uso-de-medicamentos/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ficha Tecnica Omeprazol CINFA 20 mg Cápsulas Duras Gastrorresistentes EFG [Internet]. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/63983/FT_63983.html (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- OECD Data Explorer [Internet]. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=HEALTH_PHMC%40DF_PHMC_CONSUM&df[ag]=OECD.ELS.HD&df[vs]=1.0&pd=2010%2C&dq=....A02B%2BJ01&ly[rw]=REF_AREA&ly[cl]=TIME_PERIOD&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=br (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Gendre, P.; Mocquard, J.; Artarit, P.; Chaslerie, A.; Caillet, P.; Huon, J.F. (De)Prescribing of proton pump inhibitors: What has changed in recent years? an observational regional study from the French health insurance database. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, B.; Pottie, K.; Thompson, W.; Boghossian, T.; Pizzola, L.; Rashid, F.J.; Rojas-Fernandez, C.; Walsh, K.; Welch, V.; Moayyedi, P. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2017, 63, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Targownik, L.E.; Fisher, D.A.; Saini, S.D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on De-Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urick, B.Y.; Meggs, E.V. Towards a Greater Professional Standing: Evolution of Pharmacy Practice and Education, 1920–2020. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesta-Navalón, C.; Urbieta-Sanz, E.; Gascón-Cánovas, J.J. Análisis de las interacciones medicamentosas asociadas a la farmacoterapia domiciliaria en pacientes ancianos hospitalizados. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2011, 211, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BOTPLUS. 2022. Available online: https://botplusweb.farmaceuticos.com/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Martín-Sanchez, D.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Cardenas-Villacres, D.; Carrasco, S.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. Molecular pathways driving omeprazole nephrotoxicity. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Drug Safety Communication: Low Magnesium Levels Can Be Associated with Long-Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs (PPIs). 2011. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-low-magnesium-levels-can-be-associated-long-term-use-proton-pump (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Mumtaz, H.; Ghafoor, B.; Saghir, H.; Tariq, M.; Dahar, K.; Ali, S.H.; Waheed, S.T.; Syed, A.A. Association of Vitamin B12 deficiency with long-term PPIs use: A cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond) 2022, 82, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pagès-Puigdemont, N.; Valverde-Merino, M.I. Métodos para medir la adherencia terapeútica. Ars Pharm. 2018, 59, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foro de Atención Farmacéutica-Farmacia Comunitaria (Foro AF-FC), Panel de Expertos. Guía Práctica para los Servicios Profesionales Farmacéuticos Asistenciales desde la Farmacia Comunitaria; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, P.; Ryan, C.; Byrne, S.; Kennedy, J.; Mahony, O.D. STOPP (screening tool of older person’s prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 46, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E.D.; García, M.M.; Errasquin, B.M.; Castellano, C.S.; Gallagher, P.F.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J. Prescripción inapropiada de medicamentos en los pacientes mayores: Los criterios STOPP/START. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 273–279. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-espanola-geriatria-gerontologia-124-articulo-prescripcion-inapropiada-medicamentos-pacientes-mayores-S0211139X09001310 (accessed on 10 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Homero, G.E. Polifarmacia y morbilidad en adultos mayores. Rev. Med. Clin. Condes 2012, 23, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendáriz, C.R.; Armas, D.A.; Dieppa, M.P.; de la Torre, A.H. Benzodiazepines Drug Consumption Trends in a Community Pharmacy. Assessment of the Dispensed Daily Dose. EC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Igual, S.; Lucas-Domínguez, R.; Rodrigo, A.M.; Crespo, I.R.; Mezquita, M.C.M. Atención Primaria Nuevas herramientas para la revisión de la medicación: PRM en pacientes en tratamiento con inhibidores de la bomba de protones. Aten. Primaria 2024, 56, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza Caricol, F. Seguridad del omeprazol: ¿es adecuada la duración de los tratamientos? Farm. Comunitarios 2015, 7, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wei, Y.; Yue, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, P.; Yu, F.; Xiong, A.; et al. Omeprazole and risk of osteoarthritis: Insights from a mendelian randomization study in the UK Biobank. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepisi, R.; Fusco, S.; Sganga, F.; Falcone, B.; Vetrano, D.L.; Abbatecola, A.; Corica, F.; Maggio, M.; Ruggiero, C.; Fabbietti, P.; et al. Inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors in elderly patients discharged from acute care hospitals. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 20, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtain, C.; Peterson, G.M.; Tenni, P.; Bindoff, I.K.; Williams, M. Outcomes of a decision support prompt in community pharmacy-dispensing software to promote step-down of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 71, 780–784. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21480953/ (accessed on 10 January 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alshammari, E. Irrational Prescribing Habit of Omeprazole; Departament of Pharmacy Practice, Factulty of Pharmacy, Princess Nourah Bint Abdul Rahman: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kamada, T.; Satoh, K.; Itoh, T.; Ito, M.; Iwamoto, J.; Okimoto, T.; Kanno, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Chiba, T.; Nomura, S.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, T.H. Adherence Versus Compliance. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2023, 4, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frígola Castillo, M. Estudios del uso del Omeprazol en Farmacia Comunitaria de la Costa de Girona. Diploma De Estudios Avanzados. 2008. Available online: https://melpopharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Montserrat_Frigola_Castillon.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Jensen, R.T. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Advances in treatment of gastric hypersecretion and the gastrinoma. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994, 271, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.F. Pathology of Gastritis and Peptic Ulceration. In Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics; Mobley, H.L.T., Mendz, G.L., Hazell, S.L., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Chapter 38. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2461/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- de Velasco Artaza, R.; Bueno, B.; Uría, F.; Iturbe, G. Intervención para la deprescripción de inhibidores de la bomba de protones mediante envío de carta (IBP-carta) [Intervention for proton pump inhibitors deprescribing by sending a letter (PPI-letter)]. Aten. Primaria 2022, 54, 102191. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jedlicka, P.; Bird, A.D.; Cuntz, H. Pareto optimality, economy–effectiveness trade-offs and ion channel degeneracy: Improving population modelling for single neurons. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 220073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).