In Vitro Antifungal and Topical Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Essential Oil from Wild-Growing Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Used for Medicinal Purposes in Algeria: A New Source of Carvacrol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Thyme Essential Oil Extraction

2.1.2. Yeast and Fungal Strains

2.1.3. Animals

2.1.4. Drugs and Chemicals

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil Determined by GC-MS Analysis

2.2.2. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil In Vitro

Disc Diffusion

Vapor Diffusion

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) by Agar Dilution

2.2.3. Hemolytic Activity Using Red Blood Cell (RBC) System Cellular Model In Vitro

2.2.4. In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activities

Inhibition of Denaturation of Albumin In Vitro

In Vivo Topical Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Morphologic Analysis of Mouse Ear Tissue

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

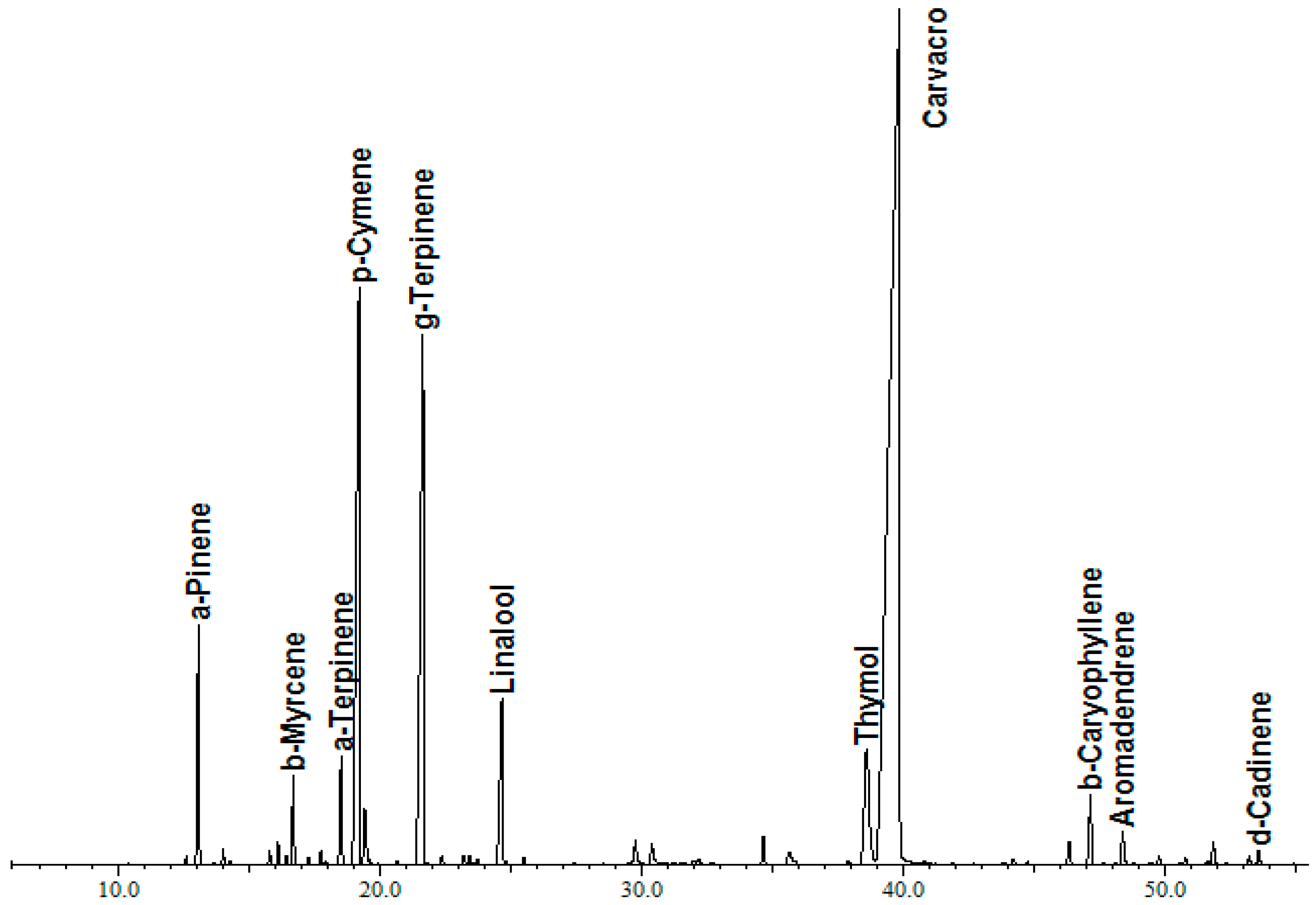

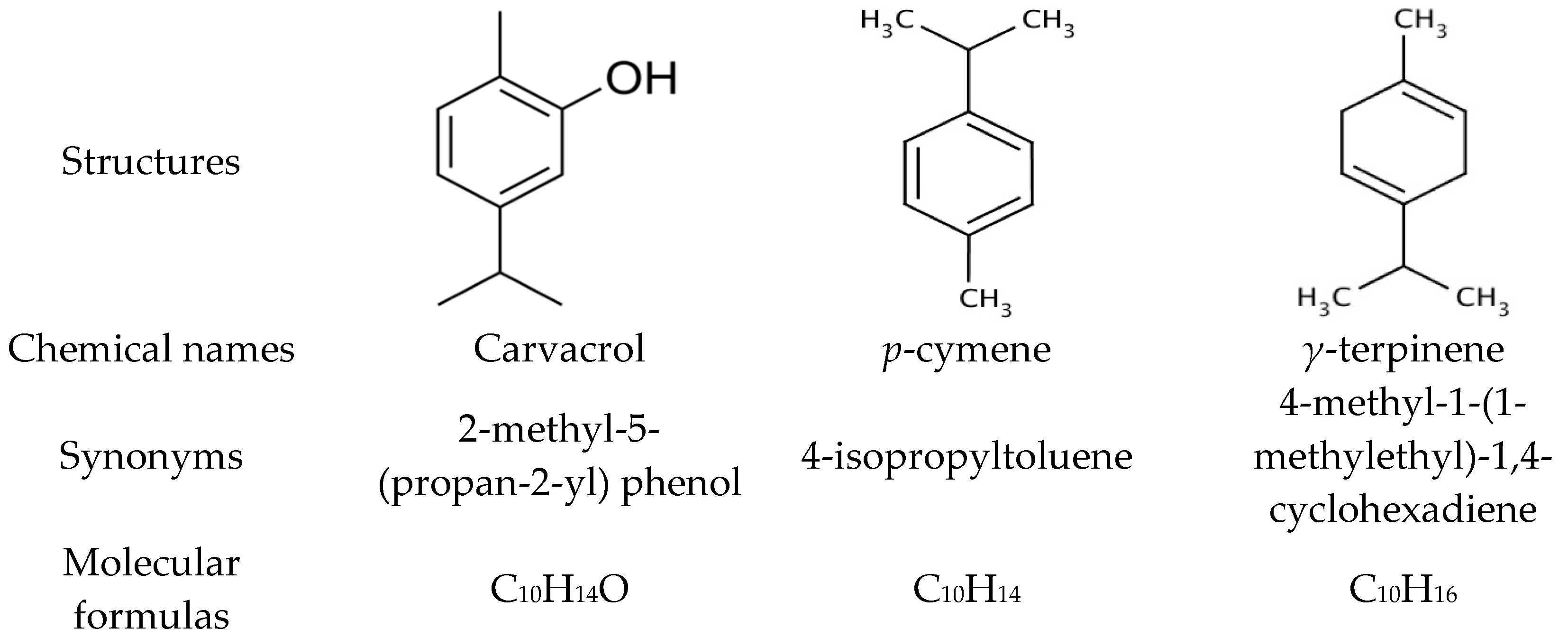

3.1. Chemical Composition of Thyme Essential Oil

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

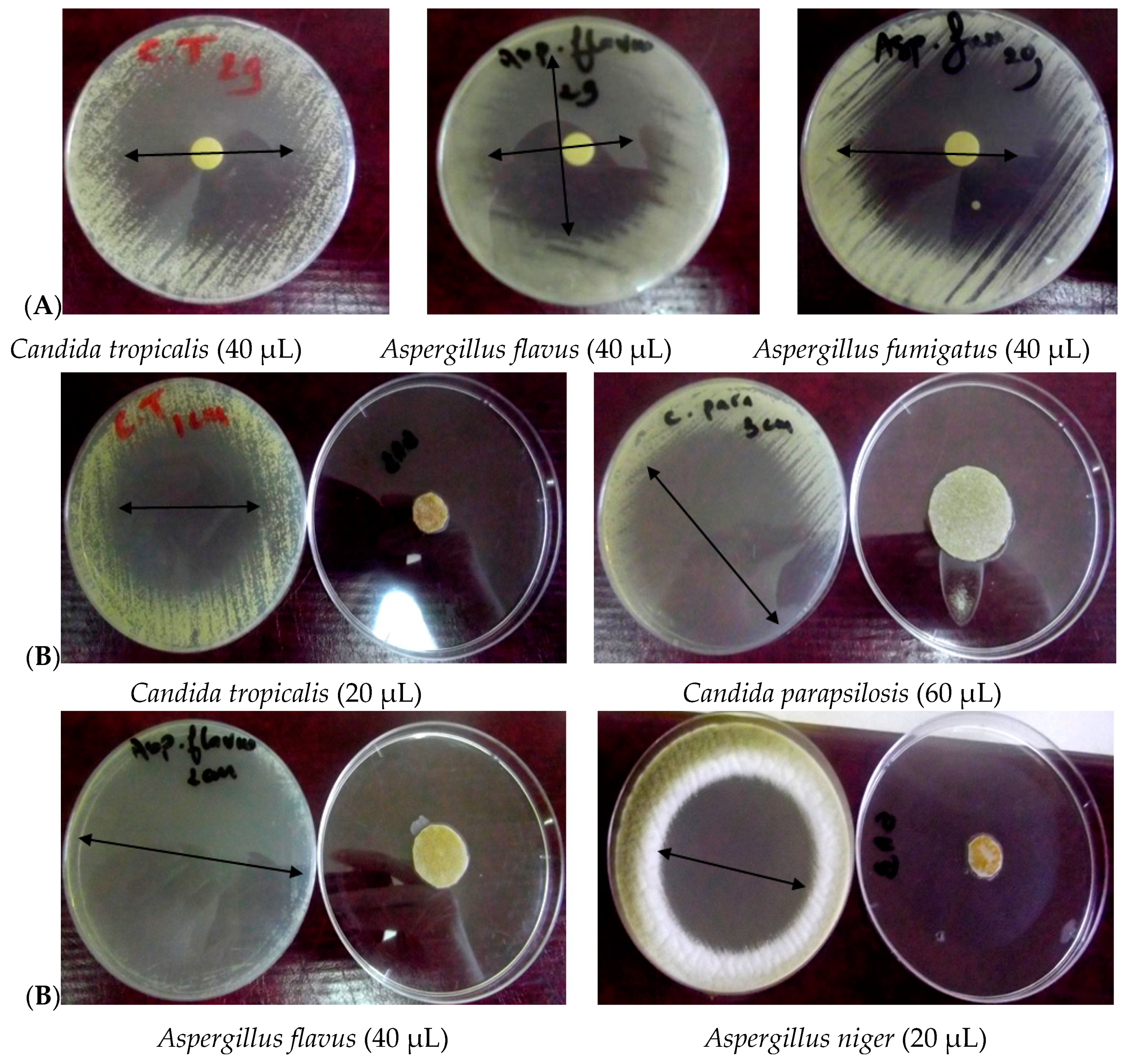

3.2.1. Disc–Diffusion Assay

3.2.2. Vapor Diffusion Assay

3.2.3. Agar Dilution Assay

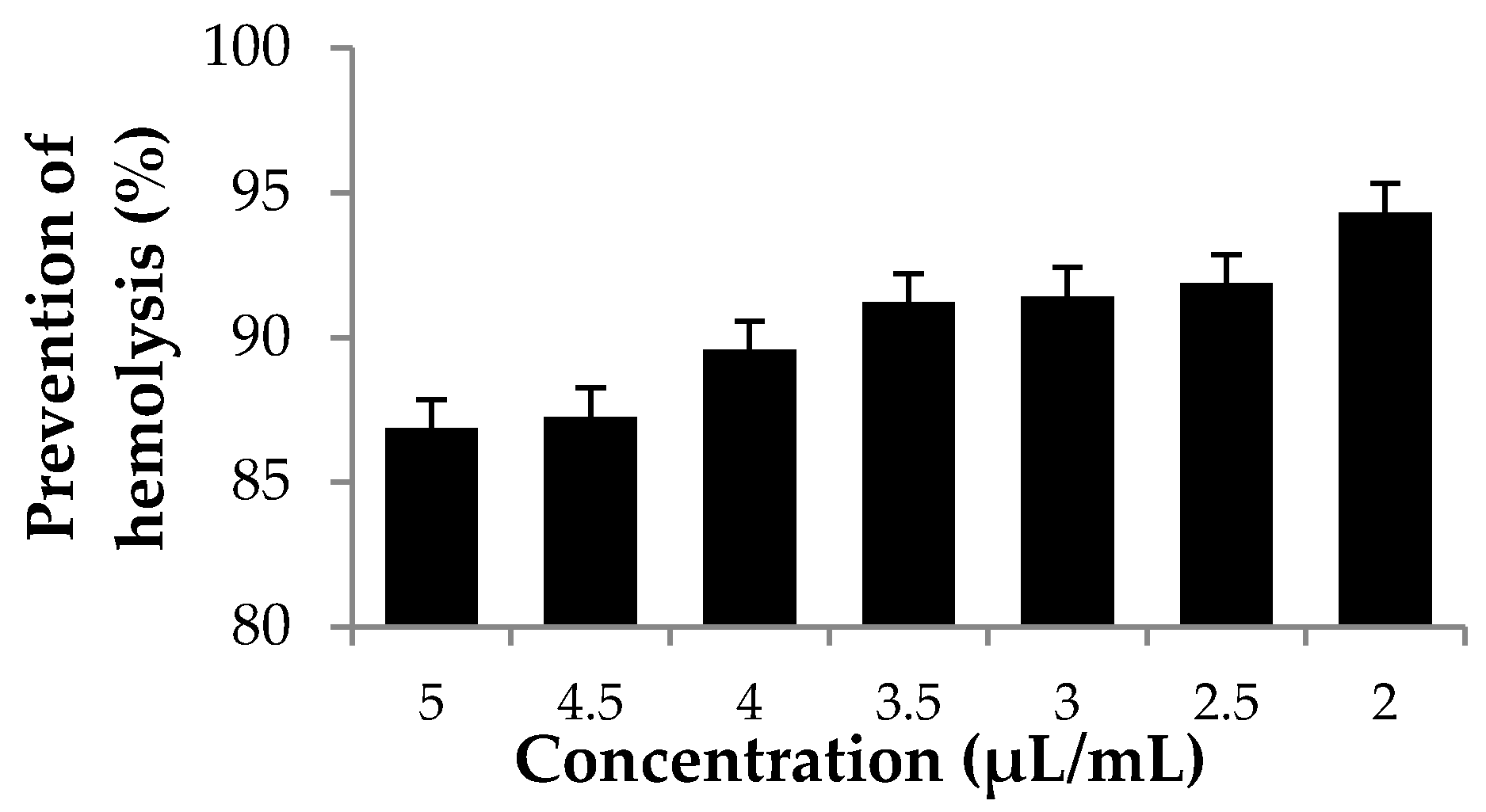

3.3. Hemolytic Activity Using Red Blood Cell (RBC) System Cellular Model In Vitro

3.4. In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.4.1. Inhibition of Denaturation of Bovine Serum Albumin In Vitro

3.4.2. In Vivo Topical Anti-Inflammatory Effect

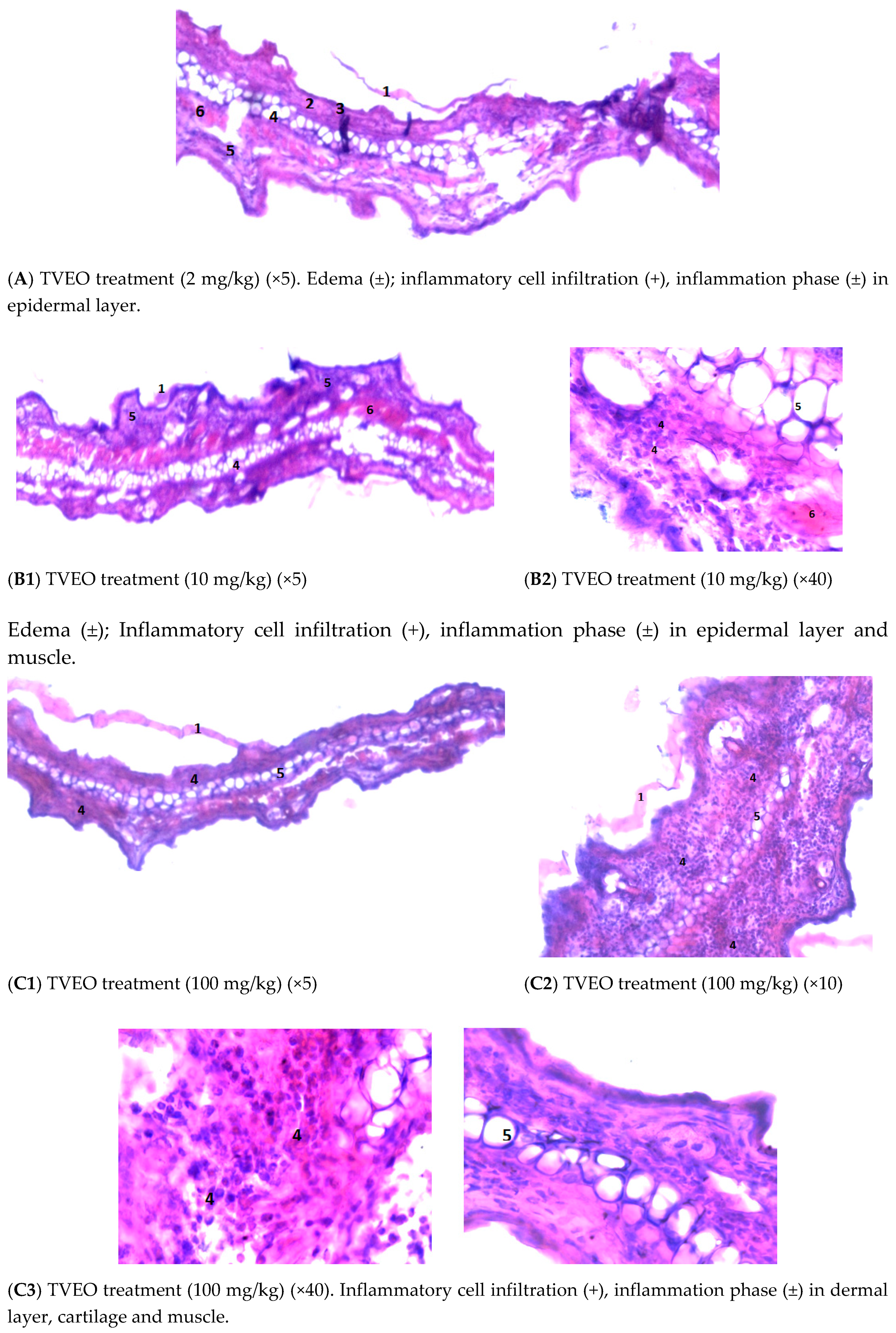

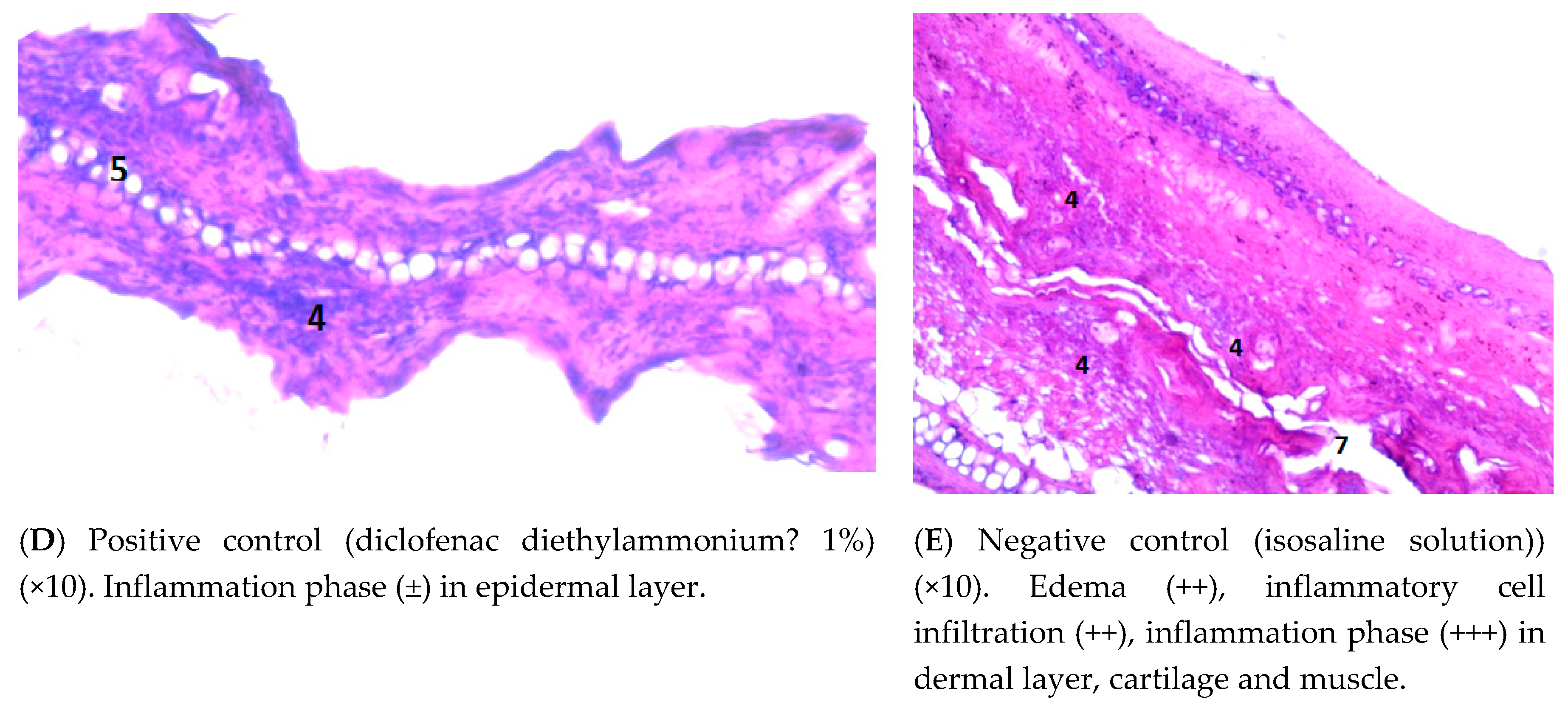

3.4.3. Examining the Mouse Ear Tissue Morphology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| DIZ | diameter of inhibition zone |

| EO | essential oil |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GRAS | generally recognized as safe |

| H&E | hematoxylin & eosin |

| IL-1 | interleukin-1 |

| Inos | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PBS | phosphate buffered saline |

| PMN | polymorphonuclear cells |

| RBC | red blood cell |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SDA | sabouraud dextrose agar–chloramphenicol |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factors |

| TVEO | Thymus vulgaris essential oil |

References

- Jarvis, W.R. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections, with emphasis on Candida species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderone, R.A.; Clancy, C.J. Candida and Candidiasis; ASM press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M.D.; Warnock, D.W. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; Salgueiro, L.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Rodrigues, A.G. Anti-Candida activity of essential oils. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlouni, M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal effects. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2010, 94, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils: A short review. Molecules 2010, 15, 9252–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachini-Queiroz, F.C.; Kummer, R.; Estevao-Silva, C.F.; Cuman, R.K.N. Effects of thymol and carvacrol, constituents of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil, on the inflammatory response. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 657026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl-Biskup, E.; Sáez, F. Thyme: The Genus Thymus; CRC Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giordani, R.; Regli, P.; Kaloustian, J.; Mikail, C.; Portugal, H. Antifungal effect of various essential oils against Candida albicans. Potentiation of antifungal action of amphotericin B by essential oil from Thymus vulgaris. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patole, V.; Chaudhari, S.; Pandit, A.; Lokhande, P. Thymol and eugenol loaded chitosan dental film for treatment of periodontitis. Indian Drugs 2019, 56, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Liquid and vapour-phase antifungal activities of selected essential oils against Candida albicans: Microscopic observations and chemical characterization of Cymbopogon citratus. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, K.; Phillips, C. Vapour phase: A potential future use for essential oils as antimicrobials? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 54, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Antimicrobial potential and chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus oil in liquid and vapour phase against food spoilage microorganisms. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrine, D.; Chenu, J.P.; Georges, P.; Lancelot, J.C.; Saturnino, C.; Robba, M. Amoebicidal efficiencies of various diamidines against twostrains of Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zaika, L.L. Spices and herbs: Their antimicrobial activity and its determination. J. Food Saf. 1988, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Filho, P.; Ferrari, M.; Maruno, M.; Souza, O.; Gumiero, V. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of nanoemulsion containing vegetable extracts. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwunmi, K.F.; Oyedapo, O.O. In vitro anti-inflammatory evaluation of African nutmeg (Monodora myristica) seeds. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2015, 8, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, R.A.; Araruna, M.K.; Oliveira, R.C.; Menezes, K.D.; Menezes, I.R. Topical anti-inflammatory effect of Caryocar coriaceum Wittm.(Caryocaraceae) fruit pulp fixed oil on mice ear edema induced by different irritant agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 136, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Reza, S.M.; Yoon, J.I.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.C. Anti-inflammatory activity of seed essential oil from Zizyphus jujube. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, M.; Chalchat, J.C. Aroma profile of Thymus vulgaris L. growing wild in Turkey. Bulg. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 30, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.J.; Martinez, R.M.; Goodner, K.L.; Baldwin, E.A.; Sotomayor, J.A. Seasonal variation of Thymus hyemalis Lange and Spanish Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils composition. Indus. Crops. Prod. 2006, 24, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, S.G.; Marin, P.D.; Dzamic, A.; Ristic, M. Essential oil composition of Thymus longicaulis from Serbia. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2009, 45, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemba, D.; Kunicka, A. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of essential oils. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 813–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Digrak, M.; Ravid, U.; Ilcim, A. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of the essential oils of Thymus revolutus Celak from Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, B.; Daferera, D.; Sökmen, M.; Sökmen, A. In vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of the essential oils and various extract of Thymus eigii M. Zohary et PH Davis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pina-Vaz, C.; Gonçalves-Rodrigues, A.; Pinto, E.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J. Antifungal activity of Thymus oils and their major compounds. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, A. Anticandidal low molecular compounds from higher plants with special reference to compounds from essential oils. Med. Res. Rev. 2006, 26, 223–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, E.; Pina-Vaz, C.; Salgueiro, L.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Thymus pulegioides on Candida, Aspergillus and dermatophyte species. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 55, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Baser, K.H. Biological and pharmacological activities of carvacrol and carvacrol bearing essential oils. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3106–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyahya, A.; Dakka, N.; Lagrouh, F.; Abrini, J.; Bakri, Y. Anti-dermatophytes activity of Origanum compactum essential oil at three developmental stages. Phytothérapie 2019, 17, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.; Sanchez, C.; Batlle, R.; Nerin, C. Solid-and vapor-phase antimicrobial activities of six essential oils: Susceptibility of selected foodborne bacterial and fungal strains. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2005, 53, 6939–6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, P.; López, P.; Sánchez, C.; Gómez-Lus, R.; Nerín, C. Antimicrobial activity in the vapour phase of a combination of cinnamon and clove essential oils. Food Chem. 2009, 16, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, M.N.; Kameli, A.; Ferhat, M.A.; Saidi, F.; Tayebi, K. The food preservative potential of essential oils: Is lemongrass the answer? J. Verbr. Lebensm. 2014, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.; Uchida, K.; Maruyama, N.; Yamaguchi, H.; Abe, S. A novel method to estimate the contribution of the vapor activity of essential oils in agar diffusion assay. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 2006, 47, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chami, F.; Chami, N.; Tennis, S.; Trouillas, J.; Remmal, A. Evaluation of carvacrol and eugenol as prophylaxis and treatment of vaginal candidiasis in an immunosuppressed rat model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Takizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, H. Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delespaul, Q.; de Billerbeck, V.G.; Roques, C.G.; Michel, G.; Bessière, J.M. The antifungal activity of essential oils as determined by different screening methods. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2000, 12, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullio, V.; Nostro, A.; Mandras, N.; Dugo, P.; Carlone, N.A. Antifungal activity of essential oils against filamentous fungi determined by broth microdilution and vapour contact methods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 1544–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Kumar, T.R.; Gupt, V.K.; Chaturvedi, P. Antimicrobial activity of some promising plant oils, molecules and formulations. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 50, 714–717. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Sato, Y.; Inoue, S.; Ishibashi, H.; Yamaguchi, H. Anti-Candida albicans activity of essential oils including Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) oil and its component, Citral. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 2002, 44, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, H.; Milella, L.; Fkih-tetouani, S.; Ilidrissi, A.; Camporese, A. In vivo topical anti-inflammatory and in vitro antioxidant activities of two extracts of Thymus satureioides leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, M.; Nakata, R.; Katsukawa, M.; Hori, K.; Takahashi, S.; Inoue, H. Carvacrol, a component of thyme oil, activates PPARα and γ and suppresses COX-2 expression. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, W.; Bahri, F.; Romane, A.; Höferl, M.; Wanner, J.; Schmidt, E.; Jirovetz, L. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of Algerian Thymus vulgaris essential oil. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 61–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Batool, S.A.; Basheer, M.I.; Shahzad, M.; Sultana, K. Ziziphora clinopodioides ameliorated rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory paw edema in different models of acute and chronic inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhatem, M.N.; Kameli, A.; Ferhat, M.A.; Saidi, F.; Mekarnia, M. Rose geranium essential oil as a source of new and safe anti-inflammatory drugs. Libyan J. Med. 2013, 8, 22520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.L.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, W.C.; Yang, C.H. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils from five selected herbs. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Chi, G.; Jiang, L.; Soromou, L.W.; Chen, N.; Huo, M.; Feng, H. p-Cymene modulates in vitro and in vivo cytokine production by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB activation. Inflammation 2013, 36, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; Marzocco, S.; Popolo, A.; Pinto, A. (−)-Linalool inhibits in vitro NO formation: Probable involvement in the antinociceptive activity of this monoterpene compound. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | RI b | Retention Time (min) | Compound a | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 926 | 13.09 | α-Pinene | 2.80 |

| 2 | 940 | 14.03 | Camphene | 0.19 |

| 3 | 969 | 15.81 | β-Pinene | 0.18 |

| 4 | 974 | 16.13 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 0.27 |

| 5 | 983 | 16.71 | β-Myrcene | 1.05 |

| 6 | 1000 | 17.75 | α-Phellandrene | 0.16 |

| 7 | 1010 | 18.54 | α-Terpinene | 1.49 |

| 8 | 1020 | 19.22 | p-Cymene | 12.8 |

| 9 | 1023 | 19.44 | Limonene | 0.79 |

| 10 | 1040 | 20.68 | cis-Ocimene | 0.04 |

| 11 | 1054 | 21.65 | γ-Terpinene | 11.17 |

| 12 | 1095 | 24.67 | Linalool | 3.06 |

| 13 | 1164 | 29.76 | Borneol | 0.47 |

| 14 | 1173 | 30.40 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0.42 |

| 15 | 1231 | 34.66 | Carvacrol Methyl Ether | 0.37 |

| 16 | 1244 | 35.64 | Pulegone | 0.44 |

| 17 | 1285 | 38.60 | Thymol | 3.99 |

| 18 | 1303 | 39.84 | Carvacrol | 56.79 |

| 19 | 1396 | 46.32 | α-Gurjunene | 0.37 |

| 20 | 1408 | 47.14 | β-Caryophyllene | 1.13 |

| 21 | 1427 | 48.37 | Aromadendrene | 0.61 |

| 22 | 1497 | 51.83 | Leden | 0.40 |

| 23 | 1500 | 53.20 | γ-Cadinene | 0.14 |

| 24 | 1506 | 53.57 | δ-Cadinene | 0.23 |

| 25 | 1562 | 57.15 | Spathulenol | 0.15 |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 65.44 | |||

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 30.67 | |||

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 2.82 | |||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 0.52 | |||

| Total | 99.51 |

| Diameter of Inhibition Zone (mm) a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc Diffusion Method | Vapor Diffusion Method | Positive Control | |||||

| Quantity of TVEO (µL per disc) | HEX c | ||||||

| 20 | 40 | 60 | 20 | 40 | 60 | ||

| Yeast Strains | |||||||

| Candida albicans (Ca1) | 34 | 40 | 50 | 40 | 50 | 85 | 29 |

| Candida albicans (Ca2) | 29 | 35 | 49 | 35 | 65 | 85 | 33 |

| Candida albicans (Ca3) | - b | 19 | 27 | 12 | 18 | 28 | 20 |

| Candida tropicalis | 55 | 55 | 60 | 50 | 70 | 85 | 22 |

| Candida parapsilosis (Cp1) | 35 | 35 | 44 | 45 | 35 | 50 | 26 |

| Candida parapsilosis (Cp2) | - | 22 | 24 | 16 | 25 | 33 | 15 |

| Trichosporon sp. | - | 13 | 13 | - | - | - | 16 |

| Rhodotorula sp. | 25 | 32 | 33 | - | 15 | 16 | 22 |

| Diameter of Inhibition Zone (mm) a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc Diffusion Method | Vapor Diffusion Method | Positive Control | |||||

| Quantity of TVEO (µL/disc) | HEX c | ||||||

| 20 | 40 | 60 | 20 | 40 | 60 | ||

| Filamentous Fungal Strain | |||||||

| Aspergillus terreus | 55 | 60 | 75 | 45 | 65 | 85 | 33 |

| Aspergillus flavus (Af 1) | 40 | 50 | 45 | 45 | 75 | 85 | 19 |

| Aspergillus flavus (Af 2) | 35 | 44 | 50 | 36 | 68 | 85 | 26 |

| Aspergillus niger (An 1) | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 42 | 50 | 26 |

| Aspergillus niger (An 2) | - b | 24 | 30 | 25 | 33 | 39 | 33 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 45 | 45 | 45 | 42 | 48 | 65 | 35 |

| Mucor sp. | 35 | 40 | 40 | 35 | 40 | 58 | 12 |

| Penicillium sp. | 30 | 50 | 45 | 40 | 42 | 45 | 29 |

| Yeast Strain | MIC (µL/mL) |

|---|---|

| Candida albicans | 0.3 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 0.3 |

| Candida tropicalis | 0.3 |

| Trichosporon sp. | 0.3 |

| Rhodotorula sp. | 0.15 |

| Treatment (s) | Dose | Absorbance (660 nm) | % Inhibition of BSA | IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 1.288 | – | – | |

| TVEO (µL/mL) | 8 | 1.149 | 10.791 | 6.843 ± 0.830 A |

| 4 | 0.066 | 94.875 | ||

| 2 | 0.047 | 96.350 | ||

| 1 | 0.047 | 96.350 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.047 | 96.350 | ||

| Sodium diclofenac (mg/mL) | 10 | 0.165 | 87.189 | 8.260 ± 0.943 A |

| 1 | 0.04 | 96.894 | ||

| 0.1 | 0.044 | 96.583 | ||

| 0.01 | 0.043 | 96.661 |

| Treatment | Dose (mg/kg) | Mean Edema Weight (mg ± SD) | % Edema Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 6.41 ± 2.45 B | – | |

| 100 | 1.98 ± 0.29 A | 73.00 | |

| TVEO | 10 | 2.33 ± 0.20 A | 68.02 |

| 2 | 2.49 ± 1.15 A | 65.69 | |

| Positive control (diclofenac diethylammonium) | 1.82 ± 0.36 A | 73.52 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boukhatem, M.N.; Darwish, N.H.E.; Sudha, T.; Bahlouli, S.; Kellou, D.; Benelmouffok, A.B.; Chader, H.; Rajabi, M.; Benali, Y.; Mousa, S.A. In Vitro Antifungal and Topical Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Essential Oil from Wild-Growing Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Used for Medicinal Purposes in Algeria: A New Source of Carvacrol. Sci. Pharm. 2020, 88, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm88030033

Boukhatem MN, Darwish NHE, Sudha T, Bahlouli S, Kellou D, Benelmouffok AB, Chader H, Rajabi M, Benali Y, Mousa SA. In Vitro Antifungal and Topical Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Essential Oil from Wild-Growing Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Used for Medicinal Purposes in Algeria: A New Source of Carvacrol. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2020; 88(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm88030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoukhatem, Mohamed Nadjib, Noureldien H. E. Darwish, Thangirala Sudha, Siham Bahlouli, Dahbia Kellou, Amina Bouchra Benelmouffok, Henni Chader, Mehdi Rajabi, Yasmine Benali, and Shaker A. Mousa. 2020. "In Vitro Antifungal and Topical Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Essential Oil from Wild-Growing Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Used for Medicinal Purposes in Algeria: A New Source of Carvacrol" Scientia Pharmaceutica 88, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm88030033

APA StyleBoukhatem, M. N., Darwish, N. H. E., Sudha, T., Bahlouli, S., Kellou, D., Benelmouffok, A. B., Chader, H., Rajabi, M., Benali, Y., & Mousa, S. A. (2020). In Vitro Antifungal and Topical Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Essential Oil from Wild-Growing Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Used for Medicinal Purposes in Algeria: A New Source of Carvacrol. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 88(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm88030033