Abstract

Mediterranean-native perennial plant Antirrhinum majus was scrutinized in this study for its antioxidant activity and its total phenolic content in order to test for the plant’s wound-healing capability. The traditional uses of this plant to treat gum scurvy, various tumors, ulcers, and hemorrhoids were the main idea behind this study. Leaves and flowers of the A. majus were extracted by maceration. Pilot qualitative phytochemical tests were made to check the presence of various secondary metabolites. Quantitatively, the flowers’ macerate indicated superlative results regarding antioxidant activity and total phenolic content. However, the in vivo wound-healing capability study was made using 30 Wistar strain albino rats. This innovative part of the study revealed that the healing power of the flowers’ extract ointment (5% w/w) was superior compared to the leaves’ extract (5% w/w) and the positive-control ointments (MEBO) (1.5% w/w) (p ≤ 0.001). This activity was assessed by visual examination, wound-length measurement, and estimation of hydroxyproline content. Antirrhinum majus is a promising plant to be considered for wound healing. However, further testing (including histological examination and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis) is necessary to understand more about its mechanisms of action.

1. Introduction

According to traditional European medicine, based on the Hippocratic theory, the human body consists of a set of elements—humors—that share nature’s principal properties with the human body. They play a major role in physical and mental health, and can be influenced by individual diet, lifestyle, geography, and seasons. They neither are true fluids nor can be isolated. These humors are Sanguis, which stands for the red blood that emerges from lesions and wounds, Phlegm for watery secretions, Choler for the yellow bile in vomit and pus, and Melancholer, perhaps for the black bile that is clotted blood in veins and stool [1]. Humanity sought balance between these humors in various ways, which is where herbal medicine played a major role in keeping that balance as ancient populations and traditions started the gathering of natural products and plants and testing their healing effects [1,2].

Generally, wounds are classified according to their healing time into acute and chronic wounds. Acute wounds resolve within less than six weeks and are a result of a physical trauma or surgery, whereas chronic wounds do not resolve within six weeks, and their causes vary according to genesis, depth, care received, and, most importantly, the blood supply to the wounded tissue [3]. Normal tissue response to injury involves three basic phases: inflammation, new tissue formation, and remodeling. Inflammation starts with the coagulation cascade in order to prevent any excess loss of blood, get rid of dead tissues, and neutralize any possible invading pathogen. A platelet plug is formed. Fibrin and neutrophils are also involved. The second phase, new tissue formation, starts shortly after the completion of the first one, where migration of keratinocytes and angiogenesis take place and replace the granulation tissue and the fibrin matrix. The remodeling phase takes place throughout the downregulation of the inflammatory cascade. Remodeling includes apoptosis of the cells involved in the repair process from the previous phase, and the replacement of dead cells by collagen and other extracellular proteins [4].

The use of plants for the stimulation of wound healing has existed since ancient empires. Aloe vera, for example, is one of the most popular plants and was used as early as 1500 BC by the ancient Egyptians for the treatment of wounds. The leaves’ gel is thought to assist in the wound-healing process by keeping the tissue moist, promoting epithelialisation and tissue oxygenation, encouraging collagen and hyaluronic acid synthesis and deposition, and ceasing inflammation [4]. Various bioactive plants’ metabolites are responsible for wound-healing activity. Polyphenols are thought of being the key components in wound healing. Polyphenols generally demonstrate antimicrobial activity, antioxidant properties that enhance cell proliferation, and collagen production [5]. Other components like alkaloids, saponins, sulphur-containing compounds, fatty oils, phytosterols, proteins, resins, and many others were also evaluated for their contribution in the wound-healing process [4].

The Antirrhinum genus was originally enlisted under the Scrophulariaceae family tree until 1995 when a study [6] came to reclassify this genus under the Plantaginaceae family [7]. Antirrhinum majus is a Mediterranean-native perennial plant, which was used historically for inheritance and mutation studies by Charles Darwin thanks to its ease of cultivation, diploid inheritance, and variation in morphology and flowers’ colors [8,9]. A. majus is used only as a decorative plant for mass display in Middle Eastern countries [10]. In some traditions, the whole-plant decoction was used for the treatment of liver ailments and to resolve watery eyes [11,12]. It was also used as a treatment for gum scurvy and various tumors, ulcers, and hemorrhoids [9].

Analyzing A. majus throughout multiple studies showed the presence of multiple active metabolites. For example, aurones, minor flavonoids, were found existing in the flowers’ petals only, giving a bright yellow color and are likely produced from chalcones [13]. Aurones play a major role acting as antioxidant and antiproliferative agents against reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species that contribute to aging, mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, and deoxyribonucleic acid damages by inhibiting oxidase enzymes [14]. On the other hand, multiple aucubin-like iridoids were found to be produced by A. majus as a defence mechanism against herbivores. These iridoids were defined as antirrhinoside, antirrhide, 5-glucosyl-antirrhinoside, linarioside, and chaenorrhinoside [15,16]. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids were found to contribute in high percentages in the seed oil of A. majus. Both can be considered of great nutritional applications regarding cardiovascular ailments, autoimmune disorders, inflammations, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. A major phytosterol constituent was reported to be present is β-sitosterol, which contributed for 65.3% of the total sterols. β-sitosterol is of great importance for hypercholesterolemia, lowering low-density lipoprotein, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Other uses include rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, hair loss, and cervical cancer. Lipid-soluble, membrane-localized antioxidants—Vitamin E tocopherols—are also present (tocopherol-α, β, γ, and δ), where γ-tocopherol represents about 81% among all [17]. Regarding the alkaloid content of A. majus, four tertiary alkaloids were qualitatively detected, and one of them was identified to be 4-methyl-2,6-naphthyridine. One water-soluble alkaloid has been identified as choline [12].

Studying the wound-healing activity of new natural products is of great importance as the world is now moving toward finding novel wound-healing agents and techniques that would lessen any possible complications with the minimum scarring at the least possible time. To our knowledge, studies that have been conducted on A. majus so far investigated the main phytochemical classes present. No research has been done before regarding the wound-healing activity of A. majus. The novelty of this study lies in scrutinizing the free-radical scavenging activity and wound-healing capabilities of the leaves and flowers of A. majus, each alone, which is cultivated in the Middle East. Our hypothesis is that the biologically active agents of A. majus extracts may improve wound healing by enhancing the rate of tissue repair.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Collection and Extraction

The whole A. majus plantlets were brought from a local arboretum in Jordan in March 2017. Plant authentication was made by The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN). Plant aerial parts were separated into flowers and leaves and blended finely using a bar blender (Waring (BB1050), Stamford, CT, USA). Both blends were soaked in 80% methanol distinctly at room temperature (RT) in a dark place for 5 continuous days over a magnetic stirrer (Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co., Schwabach, Germany). Filtration, evaporation (using rotary evaporator (30 °C, 90 rpm) (Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co. (VV2000), Schwabach, Germany)), and lyophilization (Edwards, Eastbourne, UK) were further performed on each extract. Both the leaves macerate and flowers macerate dry extracts were kept in glass vials in a freezer labeled as LM and FM, respectively.

2.2. Fractionation

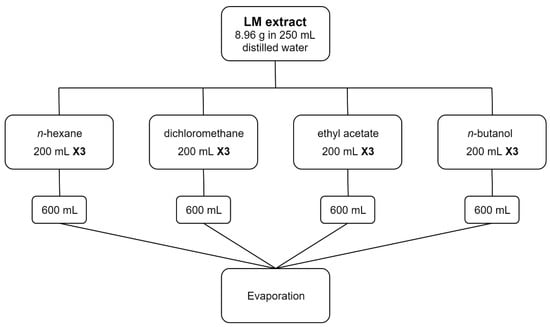

Liquid-liquid extraction of LM and FM extracts was made with the aid of a separatory funnel as the following:

LM: 8.96 g of LM extract was solubilized in 250 mL distilled water. Fractionation using increasing polarity solvents of n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol was conducted in thrice. For each step, 200 mL of each solvent was used, thus 600 mL was their final volume. Evaporation of the fractionation solvents was done using a rotary evaporator (RT, 90 rpm) (Figure 1). Evaporation of the n-butanol fraction required the addition of a random amount of anhydrous sodium sulphate and methanol, as the n-butanol forms an azeotrope with water. Mixing and filtration, then concentration over a rotary evaporator (40 °C, 90 rpm) was made.

Figure 1.

Fractionation diagram of leaves macerate extract.

FM: 4.38 g of FM extract was solubilized in 100 mL distilled water. Fractionation using 100 mL ethyl acetate was conducted thrice. The resulting 300 mL was further evaporated to its final form (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fractionation diagram of flowers macerate extract.

2.3. Phytochemical Screening

Both LM and FM crude extracts were prepared as 50 mg/mL in 1:5 dimethyl sulfoxide:methanol. These solutions were intended to be used for the following qualitative phytochemical screening:

Flavonoids:

- a.

- Sodium hydroxide test: Treatment of 0.5 mL of the extract with aqueous sodium hydroxide forms a yellow-orange colour. Upon the addition of sulphuric acid, this color disappears, indicating flavonoids presence [18].

- b.

- Lead acetate test: A few drops of 10% lead acetate are to be mixed with alcoholic solution of the extract. Formation of a yellow precipitate points out the occurrence of flavonoids [19].

Glycosides:

- c.

- Sodium hydroxide test: A small amount of alcoholic extract is dissolved in 1.0 mL water. Addition of sodium hydroxide solution produces a yellow color that specifies the presence of glycosides [19].

- d.

- Kellar Killani’s test: Extract is to be dissolved in water with the addition of glacial acetic acid and ferric chloride and concentrated sulphuric acid. The appearance of a reddish-brown ring at the junction points out the existence of glycosides [20].

Saponin glycosides:

- e.

- Froth test: Shake a slight amount of extract with 5.0 mL of water. Persistence of the foam produced for 10 min authorizes the presence of saponin [21].

- f.

- Hemolysis test: Add few drops of fresh-cut blood to 1.0 mL of extract in a test tube and mix gently. Allow the tube to stand for 15 min. Precipitation of red blood cells indicates hemolysis by saponin [22].

Alkaloids:

- g.

- Dragendroff’s test: Add a few drops of Dragendroff’s reagent to 1.0 mL of extract in a test tube. Appearance of orange colour indicates the presence of alkaloids [23].

- h.

- Picric acid test: Add a few drops of picric acid solution to 0.5 mL of extract. Formation of a yellow precipitate at the acid layer indicates the presence of alkaloids [24].

Tannins:

- i.

- Braemer’s test: Mix 0.5 mL of extract solution with 1% ferric chloride solution. Appearance of blue, green, or brownish green colour indicates tannins [24].

Phenols:

- j.

- Ferric chloride test: To 0.5 mL of extract solution add a few drops of 5% aqueous ferric chloride. Formation of deep blue to black color indicates the occurrence of phenols [25].

Anthraquinones:

- k.

- Borntrager’s test: To 1.0 mL of chloroform extract add 0.5 mL of dilute (10%) ammonia. Formation of a pink-red colour in the ammonia (lower) layer directs the presence of anthraquinones [26].

Terpenoids:

- l.

- Liebermann-Burchardt test: Add 0.5 mL of chloroform, 1.0 mL of acetic anhydride, and 1 to 2 drops of concentrated sulphuric acid to 0.5 mL of methanolic extract in a test tube. Appearance of pink or red coloration points out terpenoids [18].

- m.

- Salkowski test: Add 0.5 mL of chloroform and 0.5 mL of concentrated sulphuric acid to 0.5 mL extract in a test tube. Formation of reddish brown colour of interface specifies terpenoids [25].

Steroids:

- n.

- Liebermann-Burchardt test: Add 0.5 mL of chloroform, 1.0 mL of acetic anhydride, and 1 to 2 drops of concentrated sulphuric acid to 0.5 mL of methanolic extract in a test tube. Appearance of dark green colouration points out steroids [18].

2.4. Free-Radical Scavenging Activity by 2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulphonic Acid Cation (ABTS+) Discoloration

For the determination of the free-radical scavenging activity of the plant’s different extracts, the ABTS radical scavenging assay method that has been developed by Reference [27] was adopted. An ABTS+ solution was prepared through the reaction of 7.0 mM (3.6 mg/mL) ABTS and 2.45 mM (662.28 mg/mL) potassium persulphate, which were incubated at RT in the dark for 16 h [28]. The ABTS+ solution was then diluted with 80% ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.01 at 734 nm [29]. Stock solutions of 10 mg/mL of LM and FM in 80% ethanol were prepared. Four different dilutions were then further made from each stock as 2.0, 1.5, 1.0, 0.5 mg/mL. A volume of 3.9 mL of ABTS+ solution was added in duplicate to 0.1 mL of each dilution and mixed vigorously. The reaction mixture was allowed to stand at RT for 6 min and the absorbance at 734 nm was immediately read in quartz cuvettes using a spectrophotometer (Dr. Akid SCO GmbH, Dingelstädt, Germany) [28]. A standard curve was obtained using Trolox standard solution at various concentrations ranging from 0 to 15 mM (0 to 3.75 mg/mL) in 80% ethanol [30]. Data are expressed as ABTS+ scavenging percentage according to the following equation [31]:

where As: absorbance of sample at 734 nm; Ab: absorbance of blank at 734 nm.

2.5. Total Phenolic Content by Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent

To quantitatively determine the total phenolic content in LM and FM extracts, the Folin-Ciocalteu procedure described by Reference [32] was adopted in this part. A stock solution of 10 mg/mL of both extracts was prepared in distilled water. Furthermore, 4 different dilutions were made from each stock as 1.0, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125 mg/mL. Concisely, 12.5 μL of each prepared dilution was mixed with 250 μL of 2% sodium carbonate solution in a 96-well microplate in duplicate. Plates’ contents were allowed to react for 5 min at RT. Then, 12.5 μL of 50% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added and allowed to react again for 30 min at RT. Reaction-mixture absorbance was read using a plate reader (Biotek (EL-x800), Winooski, VT, USA) at 630 nm [33]. Gallic acid standard solution at various concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/mL in distilled water was used as a reference. Results are shown as equivalent of Gallic acid (mg) for each mL of each extract [32].

2.6. Wound-Healing Activity

The wound-healing part of this study was applied to 30 Wistar strain albino rats of both genders aged 8–12 weeks. Average weight was 298.79 ± 7.31 g. Rats were obtained from the Animal House of Applied Science University. They were organized into two groups (15 rats per group) in metal cages within the Animal House of Applied Science University. Rats were maintained under standard environmental conditions (12 h dark/12 h light), and supplied with food and water ad libitum [34]. Animal care and use were conducted according to standard ethical guidelines, and all of the experimental protocols were approved by the Research and Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Pharmacy Applied Science University (Approval code: Pharm-2017-6 (June 2017)).

2.6.1. Ointments Preparation

LM and FM extracts were formulated as 5% w/w ointments. Ointment vehicle alone was used as a negative control, where 1.5% w/w MEBO was used as a positive control (Table 1) [35]. Gentle heat was used to melt the white petrolatum. Agitation until an appropriate semisolid texture of the ointments was endured. Ointments were placed in the refrigerator for the entire study duration.

Table 1.

Formula used to prepare the extracts’ and the control ointments.

Moist Exposed Burn Ointment (MEBO) is a petrolatum-based natural preparation. It was developed in the 1980s by the China National Science and Technology Center. It is extensively used in Asia and the Middle East in the healing of wounds and burns. β-sitosterol, a plant steroid, is the main active ingredient in MEBO that is responsible for the anti-inflammatory effect. Sesame oil and berberine are also present, providing a moist environment that encourages epithelialization. Continuous application of MEBO was reported to cease dermal irritation a sensitization, and relieve pain [36,37].

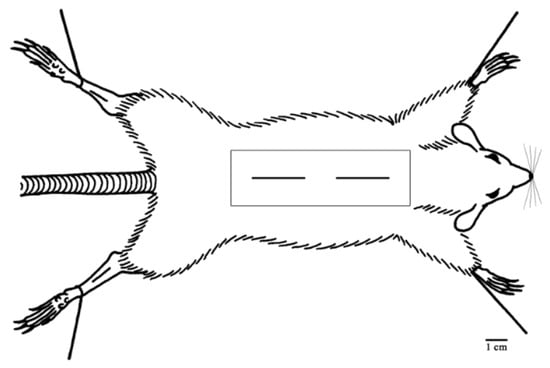

2.6.2. Rats Wounding

Wound-healing activity was tested according to the method described by Reference [38]. Anesthetization with 350 mg/Kg of 5% chloral hydrate solution intraperitoneally was considered before the wounding [39]. Rats’ dorsal sides were shaved using a shaving blade and rubbed with 76% ethanol. Two 2.5 ± 0.06 cm longitudinal incisional dorsal wounds were made with the aid of a surgical blade until the deep fascia along the midline for each rat. The wound closer to the head is referred to as “TOP”, whereas the lower one as “BOTTOM” (Figure 3) [40,41]. Longitudinal incisions were considered to be made due to the fact that they are more common in our daily life than excisional wounds. To ensure good closure of the wound, the two edges of each wound were tightened and stitched with one stitch using a silk surgical thread and a curved needle [42]. Wounds were left undressed and examined daily for evidence of infection. Use of antibiotics was not considered either topically or systemically. Rats were housed in individual cages.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the longitudinal incisional wounds that were made on the dorsal side of each rat.

Rats were divided into two groups (n = 15 per group), active and control groups. The active group was meant to test the wound-healing activity of extracts, where LM ointment was applied to the TOP wound, and FM ointment was applied to the BOTTOM one. The control group was meant to compare the wound-healing activity of the positive and negative controls with that of the extracts, where the TOP wound was applied with the negative control ointment, and the BOTTOM one was applied with the positive control ointment. This wound-healing study was held for 12 days, where the day of wounding was considered as day 1. Ointments were applied in an amount just enough to cover the wound length once daily with the aid of a metal spatula.

2.6.3. Evaluation of Wound-Healing Activity

Visual Examination

All wounds were examined visually for signs of inflammation and to monitor the healing process on day 1, 4, 8, and 12. An HTC One E9PLUS phone camera (27.8 mm, 20 megapixels) was used to take photos of the wounds.

Wound-Length Measurement

Wound length was measured on day 4, 8, and 12 for each wound using a digital caliper (Starrett, Athol, MA, USA). Length reduction rate (mm/day) was defined as the following equation [43]:

where L1: wound length (mm) at day 1; LT: wound length (mm) at the defined time (days); T: time (days).

Estimation of Hydroxyproline Content

Hydroxyproline content was estimated according to the method developed by Reference [44]. On day 4 and 8, two rats of each group were sacrificed by inhaling diethyl ether in a well-sealed desiccator, and on day 12 all the remaining rats were sacrificed in the same way. A full-depth piece of skin (70 mm2) from the healed wound area was taken using scissors and a surgical blade. The skin was washed with normal saline and dehydrated in an oven (J.P Selecta, Barcelona, Spain) at 60–70 °C to a constant weight. The dehydrated skin was then hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl (1 mL HCl/10 mg skin) at 130 °C for 4 h in sealed Pyrex-glass tubes [45,46]. An aliquot of 20 µL of each hydrolysate was added to a 96-well plate and incubated with 50 µL per well of chloramine T solution (oxidizing agent) for 20 min at RT. Subsequently, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 µL of Ehrlich’s reagent (p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde) (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) in each well and incubated for 15 min in the oven at 65 °C. Absorbance was read using a plate reader at 550 nm. A standard curve was obtained using pure hydroxyproline solution at various concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 µg/mL. Results are expressed as µg/mL of hydroxyproline [47].

Chloramine T solution was prepared according to a formula of 282 mg chloramine T, 2 mL n-propanol, 2 mL distilled water, and 16 mL citrate-acetate buffer [47]. In contrast, the citrate-acetate buffer was prepared by mixing 5% citric acid, 7.24% sodium acetate, 3.4% sodium hydroxide and 1.2% glacial acetic acid [48].

2.6.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS Statistics 23. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (Standard Error of Mean). The statistical significance among rats’ groups of wound-healing activity was determined applying one-way and two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Fractionation

Fractions are extracted depending on the fractionation-solvent polarity. Results are shown as yield (mg) fraction for each gram of extract (mg/g) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Yield as mg fraction per 1 g of extract (mg/g) of various fractions of LM and FM extracts.

3.2. Phytochemical Screening

Qualitative phytochemical screening was made as a pilot study about the possible phytoconstituents existing within A. majus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Qualitative phytochemical screening of both Antirrhinum majus extracts.

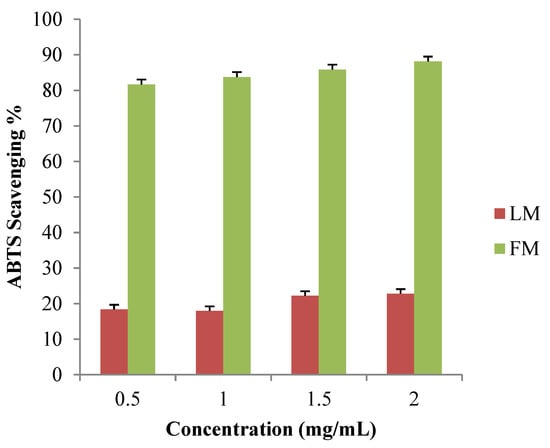

3.3. Free-Radical Scavenging Activity by ABTS+ Discolouration

ABTS radical-scavenging assay was used to generate blue/green ABTS+ cation. A concentration range of 0.5–2.0 mg/mL was examined for LM and FM. Absorbance at 734 nm was read and used to determine the ABTS+ scavenging percentage. FM extract showed the highest ABTS scavenging activity at all the tested concentrations between 81.64% and 88.13%. The leaves extracts showed very low ABTS scavenging activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ABTS+ scavenging percentage of LM and FM extracts.

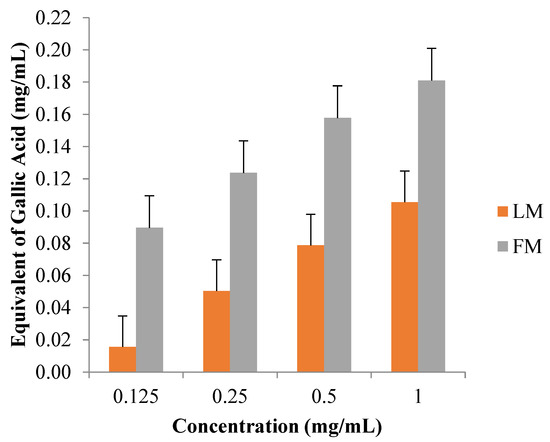

3.4. Total Phenolic Content by Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent

Concentrations in the range of 0.125–1.0 mg/mL were tested for both extracts, LM and FM. Absorbance at 630 nm was used to express the extracts’ total phenolic content. FM extract indicated the highest equivalent of gallic acid (mg/mL) in comparison with LM extract (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Equivalent of gallic acid (mg) per 1 mL extract of LM and FM extracts.

3.5. Wound-Healing Activity

Wound-healing assessment was conducted for twelve days by making two 2.5 ± 0.06 cm longitudinal incisional dorsal wounds along the midline of each rat. The duration of this study was determined by the fastest wound to heal. Ointments of 5% w/w of both extracts were made in glycerol and white petrolatum. Vehicle alone and 1.5% w/w MEBO were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Ointments were applied once daily. Wounds were assessed every four days visually, via wound-length measurement, and by means of hydroxyproline content estimation.

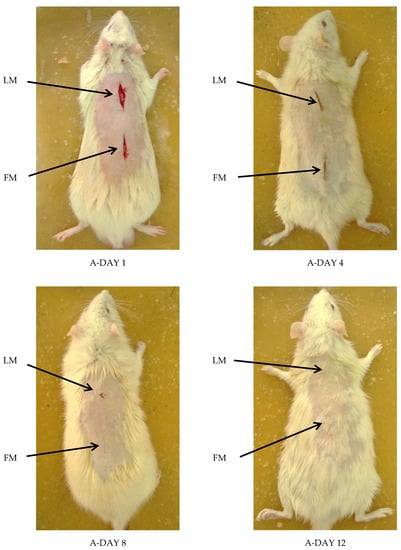

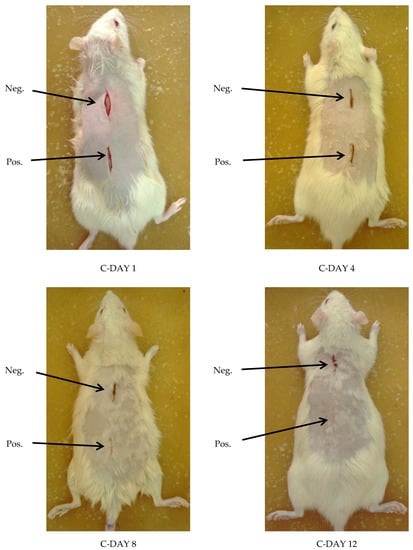

3.5.1. Visual Examination

Examining wounds’ signs of inflammation and monitoring the healing process on day 1, 4, 8, and 12 for each rat was done. FM ointment showed the best results and the fastest healing rate. On the contrary, LM ointment results and rate of healing were almost the same as the positive control ointment. However, the negative control ointment was the least effective as granulation of the wound was still noticed even on the twelfth day of wounding. No signs of complications were noticed (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Visual examination of ACTIVE group rats at day 1, 4, 8, and 12, where the TOP wound represents the LM extract ointment, and the BOTTOM one represents the FM extract ointment.

Figure 7.

Visual examination of CONTROL group rats at day 1, 4, 8, and 12, where the TOP wound represents negative control ointment (Neg.), and the BOTTOM one represents positive control ointment (MEBO) (Pos.).

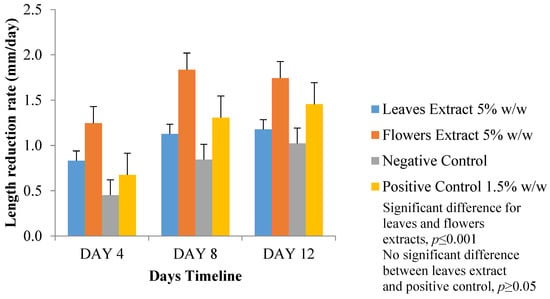

3.5.2. Wound-Length Measurement

Length reduction rate (mm/day) was considered to normalize our results (Figure 8). Again, FM ointment showed the largest length reduction rate, whereas LM ointment results were very close to those of the positive control ointment. The negative control ointment was the least effective. A significant difference of p ≤ 0.001 (one-way ANOVA) in the wound-length measurement results was found in all four wounds between day 1 and day 12. Another significant difference of p ≤ 0.001 (two-way ANOVA) was found when comparing FM ointment results with the other three tested ointments. No significant difference (p ≥ 0.05, two-way ANOVA) between the LM and positive control ointments was found.

Figure 8.

Wound-length reduction rate (mm/day) at day 4, 8, and 12.

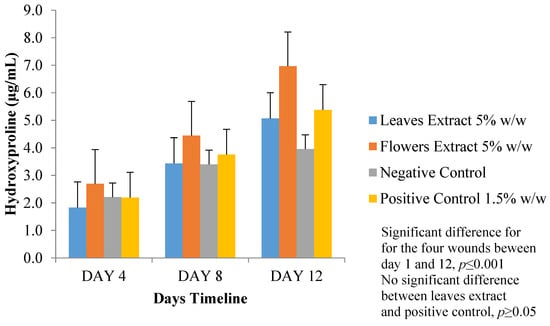

3.5.3. Estimation of Hydroxyproline Content

Skin hydrolysate was analyzed for its hydroxyproline content at 550 nm using a plate reader. Results are expressed as µg/mL of hydroxyproline, where FM ointment showed the highest hydroxyproline content that indicates high collagen content and, thus, better wound healing. Both LM and positive control ointment-treated-wounds results were very comparable. The negative control ointment resulted in the least amount of hydroxyproline (Figure 9). A significant difference of p ≤ 0.001 (one-way ANOVA) in the estimation of hydroxyproline content results was found in all of the four wounds during the total study duration. Another significant difference of p ≤ 0.001 (two-way ANOVA) was found comparing FM ointment results with the other three tested ointments. No significant difference (p ≥ 0.05, two-way ANOVA) between the LM and positive control ointments was found.

Figure 9.

Hydroxyproline content (µg/mL) at day 4, 8, and 12.

4. Discussion

Fractionation is a simple and cost-effective method for the partitioning and quantification of mixtures and extracts. Partitioning is affected by extractant type, the volumes ratio between the organic and the aqueous phases, and the aqueous phase pH [49]. Multiple immiscible and partially miscible increasing polarity extractants were used for the process of liquid-liquid extraction. Distribution of the crude extracts’ components occurred with n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol. Apparently, FM extract contains a higher quantity of the ethyl acetate miscible components than that of LM. Qualitative phytochemical screening of both extracts indicated the presence of all the tested secondary metabolites except for the saponin glycosides.

Quantitatively, FM extract revealed the highest antioxidant activity and total phenolic content. These results are believed to be due to the flowers’ high content of flavonoids and phenolics. The same effect was seen by References [50,51] studying the total phenolic and total flavonoid contents of various plants.

The wound-healing capability of A. majus was investigated for both extracts. All three followed methods for the assessment of wound-healing activity (i.e., visual examination, wound-length measurement, and estimation of hydroxyproline content) indicated better wound closure and healing in the active group rather than the control group. This wound-healing effect of the flowers and leaves of A. majus is related to their antioxidant activity. The interrelation of antioxidant activity and wound-healing effect was studied recently by Reference [52] on diabetic mice. The study findings denoted that diabetes leads to depleted levels of proinflammatory cytokines that result in delayed inflammatory cascade, and thus a slower healing process. Adjunctive administration of antioxidants during the wound-healing process restored the proper levels of multiple cytokines. More importantly, this biological effect is probably a result of β-sitosterol and tocopherol isomers. They both were identified in the seed oil of A. majus [12,17]. The same finding was a result of a study [53] where it was agreed that phytosterols are of great importance for efficient wound healing.

5. Conclusions

Five distinct increasing-polarity extractants were used through the whole study. This use of such wide range of extractant polarity was meant to partition the plant components. Upon qualitative screening for existing secondary metabolites, saponin glycosides were the only group that was not detected. Quantitatively, the free-radical scavenging activity and the total phenolic content were assessed against Trolox and gallic acid standard curves, respectively. FM exhibited the utmost results because of its noteworthy content of flavonoids and phenols.

Surprisingly, the novelty of this study lies within the wound-healing activity of FM. FM extract activity was superior to that of LM and the positive control (i.e., MEBO) ointments (p ≤ 0.001). This superior activity is referenced mainly due to the plant phytosterols and tocopherols content in addition to the flavonoids and phenols.

We would recommend to test the root of A. majus for its wound-healing and cytotoxic effects, which may carry immense potential, superior to that of the flowers. Additionally, further testing using histological examination and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis would help to provide more insight of the mechanisms of action of this plant.

Author Contributions

This article was submitted as part of F.G.S. master degree thesis. Conceptualization, W.M.H. and F.G.S.; Methodology, F.G.S.; Software, F.G.S.; Validation, W.M.H. and W.H.T.; Formal Analysis, F.G.S.; Investigation, F.G.S.; Resources, W.H.T.; Data Curation, F.G.S., W.M.H. and W.H.T.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, F.G.S.; Writing-Review and Editing, F.G.S. and W.H.T.; Visualization, F.G.S.; Supervision, W.M.H. and W.H.T.; Project Administration, W.M.H. and W.H.T.; Funding Acquisition, W.H.T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan for the full financial support granted to this research project. We would also like to warmly thank Qamar Atari, Fawzi Al-Arini, Salem Al-Shawabkah, Eilaf Sabbar, and Noor Sabah for their supportive and skilful assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Totelin, L. Hippocratic recipes; oral and written transmission of pharmacological knowledge in fifth- and fourth-century greece. In Studies in Ancient Medicine; Scaborough, J., Van der EiJk, P., Hanson, A., Siraisi, N., Eds.; Brill Academic Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2009; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, Z.; Dudai, N. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the Middle-East; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, R.; Romanelli, M.; Shukla, V. Measurements in Wound Healing: Science and Practice; Springer: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Budovsky, A.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Ben-Shabat, S. Effect of medicinal plants on wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.; Gaba, A. Phyto-extracts in wound healing. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 16, 760–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmstead, R.; Reeves, P. Evidence for the polyphyly of the scrophulariaceae based on chloroplast rbcl and ndhf sequences. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1995, 82, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, D.; Beardsley, P.; Kelchner, S.; Olmstead, R. Review of the systematics of Scrophulariaceae s.l. and their current disposition. Aust. Syst. Bot. 2006, 19, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, A.; Critchley, J.; Erasmus, Y. The genus antirrhinum (snapdragon): A flowering plant model for evolution and development. CSH Protoc. 2008, 2008, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T. Antirrhinum majus. In Edible Medicinal and Non Medicinal Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 8, pp. 633–639. [Google Scholar]

- Taifour, H.; El-Oqlah, A. Jordan Plant Red List; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 1, p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Snafi, A. The pharmacological importance of Antirrhinum majus—A review. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Harkiss, K. Studies in the scrophulariaceae—Part III investigation of the occurrence of alkaloids in antirrhinum majus L. Planta Med. 1971, 20, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.; Marshall, G.; Bradley, J.; Schwinn, K.; Bloor, S.; Winefield, C.; Martin, C. Characterisation of aurone biosynthesis in Antirrhinum majus. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 128, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotewold, E. The Science of Flavonoids; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–5, 147–155, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Franzyk, H.; Frederiksen, S.; Jensen, S. Synthesis of antirrhinolide, a new lactone from Antirrhinum majus. Eur. J. Organ. Chem. 1998, 1998, 1665–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogedal, B.; Molgaard, P. HPLC analysis of the seasonal and diurnal variation of iridoids in cultivars of Antirrhinum majus. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2000, 28, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; El-Shamy, H. Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) seed oil: Characterization of fatty acids, bioactive lipids and radical scavenging potential. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 42, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabri, T.; Al Musalami, A.; Hossain, M.; Weli, A.; Al-Riyami, Q. Comparative study of phytochemical screening, antioxidant and antimicrobial capacities of fresh and dry leaves crude plant extracts of Datura metel L. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2014, 26, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, T.; Geetha, N. Phytochemical screening, quantitative analysis of primary and secondary metabolites of Cymbopogan citratus (DC) stapf. leaves from kodaikanal hills, tamilnadu. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2014, 6, 521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi, K.; Oladapo, O.; Okwara, C.; Ibe, C.; Fasure, K. Screening of crude extracts of six medicinal plants used in south-west nigerian unorthodox medicine for anti-methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus activity. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.; AL-Raqmi, K.; AL-Mijizy, Z.; Weli, A.; Al-Riyami, Q. Study of total phenol, flavonoids contents and phytochemical screening of various leaves crude extracts of locally grown thymus vulgaris. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Zakir, A.; Shemau, Z.; Abdullahi, M.; Halima, S. Phytochemical analysis of the methanol leaves extract of Paullinia pinnata L. J. Pharm. Phytother. 2014, 6, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Wahab, F.; Jalil, T. Study of iraqi spinach leaves (phytochemical and protective effects against methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity in rats). Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 21, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Khare, R.; Singhal, A. Qualitative phytochemical screening of some selected medicinal plants of shivpuri district (mp). Int. J. Life Sci. Sci. Res. 2017, 3, 844–847. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, Z.; Wen, C.; Bhat, I. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activity of root and stem extracts of wild Eurycoma longifolia jack (tongkat ali). J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2015, 27, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeshwari, C.; Kalaichelvi, K. Comparitive phytochemical screening of acmella calva (dc.) rk jansen and crotalaria ovalifolia wall: Potential medicinal herbs. J. Med. Plant. 2017, 5, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved abts radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, L.; El Arem, A.; Ghrairi, F.; Chahdoura, H.; Salem, H.; El Felah, M.; Achour, L. Phytochemical content and antioxidant properties of diverse varieties of whole barley (hordeum vulgare L.) grown in tunisia. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.; Cercato, L.; de Santana Souza, M.; de Oliveira Melo, A.; dos Santos Lima, B.; Duarte, M.C.; de Souza Araujo, A.; e Silva, A.; Camargo, E. The ethanol extract of Leonurus sibiricus L. induces antioxidant, antinociceptive and topical anti-inflammatory effects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Nakagawa, T.; Kishikawa, A.; Ohnuki, K.; Shimizu, K. In vitro bioactivities and phytochemical profile of various parts of the strawberry (fragaria × ananassa var. Amaou). J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintola, O.; Afolayan, A. Chemical constituents and biological activities of essential oils of Hydnora africana thumb used to treat associated infections and diseases in south africa. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, A.; Flanagan, J.; Wei, W.; Moughan, P. Selenium-containing green tea has higher antioxidant and prebiotic activities than regular green tea. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, A.; Yousif, A.; Al-Bayati, N. Total phenolic contents and antiradical activities of pomaces and their ingredients of two iraqi date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 6, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ritskes-Hoitinga, J.; Jilge, B. Felasa—Quick Reference Paper on Laboratory Animal Feeding and Nutrition; AAALAC: Frederick, MD, USA, 2001; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Cao, X.; Nie, J.; Fu, L.; Chen, L.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Evaluation of effectiveness in a novel wound healing ointment-crocodile oil burn ointment. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, E.; Lee, S.; Gan, C.; See, P.; Chan, Y.; Ng, L.; Machin, D. The role of alternative therapy in the management of partial thickness burns of the face—Experience with the use of moist exposed burn ointment (mebo) compared with silver sulphadiazine. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2000, 29, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jewo, P.; Fadeyibi, I.; Babalola, O.; Saalu, L.; Benebo, A.; Izegbu, M.; Ashiru, O. A comparative study of the wound healing properties of moist exposed burn ointment (mebo) and silver sulphadiazine. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2009, 22, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, S.; Singhai, A. Preliminary pharmacological evaluation of Martynia annua linn leaves for wound healing. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2011, 1, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowland, M. Guidelines on Anesthesia and Analgesia in Rats. Available online: https://az.research.umich.edu/animalcare/guidelines/guidelines-anesthesia-and-analgesia-rats (accessed on 6 August 2017).

- Asmis, R.; Qiao, M.; Zhao, Q. Low flow oxygenation of full-excisional skin wounds on diabetic mice improves wound healing by accelerating wound closure and reepithelialization. Int. Wound J. 2010, 7, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkaman, G. Electrical stimulation of wound healing: A review of animal experimental evidence. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Garg, A.; Sharma, P.; Pandey, P. Wound healing and antioxidant effect of Calliandra haematocephala leaves on incision and excision wound models. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 2, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Siavash, M.; Shokri, S.; Haghighi, S.; Shahtalebi, M.; Farajzadehgan, Z. The efficacy of topical royal jelly on healing of diabetic foot ulcers: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. Wound J. 2015, 12, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woessner, J. The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1961, 93, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, D.; Dwivedi, M.; Malviya, S.; Singh, V. Evaluation of wound healing, anti-microbial and antioxidant potential of Pongamia pinnata in wistar rats. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.; O’brien, W. Modified assay for determination of hydroxyproline in a tissue hydrolyzate. Int. J. Clin. Chem. Diagn. Lab. Med. 1980, 104, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.; Madjarof, C.; Ruiz, A.; Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, R.; de Oliveira Sousa, I.; Foglio, M.; de Carvalho, J. Evaluation of wound healing properties of Arrabidaea chica verlot extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronska-Kozak, B.; Bogacki, M.; Rim, J.S.; Monroe, W.; Manuel, J. Scarless skin repair in immunodeficient mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2006, 14, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadi, A.; Partoazar, A.; Abedi-Khorasgani, M.; Shetab-Boushehri, S. Comparison of liquid-liquid extraction-thin layer chromatography with solid-phase extraction-high-performance thin layer chromatography in detection of urinary morphine. J. Biomed. Res. 2011, 25, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.; Gillespie, K. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using folin-ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Ma, H.; Fan, P.; Gao, R.; Jia, Z. Antioxidant potential, total phenolic and total flavonoid contents of Rhododendron anthopogonoides and its protective effect on hypoxia-induced injury in pc12 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa, A.; Florim, J.; Rodrigues, H.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Teixeira, S.; Vitzel, K.; Curi, R.; Saraiva Câmara, N.; Muscará, M.; Lamers, M.; et al. Oral administration of antioxidants improves skin wound healing in diabetic mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardaa, S.; Halima, N.; Aloui, F.; Mansour, R.; Jabeur, H.; Bouaziz, M.; Sahnoun, Z. Oil from pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seeds: Evaluation of its functional properties on wound healing in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2016, 15, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).