Abstract

This study reviews Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology and provides a detailed analysis to aid understanding of the book, combined with diverse scholars’ perspectives in the fields of economic history, political economics, and social sciences. This book is selected as my review target to answer the following research question, “How do we conquer the growth limits of capitalism?” This book gave me several ideas for the basis of my future research. In this review paper, I provide a guide for readers to understand ways to conquer the growth limits of capitalism. My study also provides a creative understanding of the evolution of the capitalist economy from new perspectives. In particular, it presents an analysis of Piketty’s diverse policy ideas from the viewpoint of a global history of capitalism. This will give a new lens through which to focus on understanding and resolving the inequalities of 21st-century hyper-capitalism and to construct policy for the current world economy. Finally, this study offers a causal loop model of Piketty’s findings and proposals, and suggests future research topics.

1. Introduction

Upon reading Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century [1], a serial analysis about the worsening inequality in the ratio between capital revenue and labor income, I experienced an intellectual shock. His proposal for capital tax had previously motivated me to study the economic system with feedback loops on decreasing inequality, motivating open innovation, and increasing entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics [2]. Then, I published several papers on Schumpeterian or entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics in social, market, and closed open innovations [3,4].

The sales of Capital in the Twenty-First Century in Korea in December 2015 were the 8th highest in the world, totaling 88,000 copies. The book also sparked a debate about economic inequality, particularly as one of the reasons for Korea’s limited economy growth [5]. In The Economics of Inequality, Piketty and Goldhammer assert that in the economic history of France and Europe, there is no evidence for the Kuznets curve, but several concrete proofs of r > g (where r stands for the average annual rate of return on capital, including profits, dividends, interests, rents, and other income from capital, expressed as a percentage of its total value; and g stands for the rate of growth of the economy, i.e., the annual increase in income or output) [6,7]. The difference in amount between two ratios played a crucial role as the fundamental force for divergence in the 21st century [1] (Piketty expressed α = r × β as the first fundamental law of capitalism, where r is the rate of return on capital; β is the capital/income ratio; and α is the rate of return on capital, which is a broader notion of the “rate of profit,” or “rate of interest.”). In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Piketty stated that the rate of return on capital has always been higher than the world economic growth rate; however, the gap was reduced during the 20th century, but may widen again in the 21st century.

Diverse economists have criticized Capital in the Twenty-First Century because r > g is not a logical inevitability, even though Nobel laureate Robert M. Solow supported Piketty [6]. Piketty stated only the second fundamental law of capitalism: β = s/g, where s= saving rate. This formula reflects an obvious and important point—that if a country has a high savings rate and grows slowly, over the long run, it will accumulate an enormous stock of capital (relative to its income), which can, in turn, have significant divergence effects on the social structure and distribution of wealth [5]. Additionally, Piketty showed that the capital/income ratio over the long run reflected an increasing trend from the 1950s in the United States and Europe.

In Capital and Ideology, Piketty analyzed diverse mechanisms supporting r > g, which had been long operating in the economic history of regimes of inequality, for example, ternary societies; European societies of orders or ownership societies; slave and colonial societies; and even in the great transformational changes of the 20th century, such as the crisis of ownership societies, social-democratic societies, communist and post-communist societies, or hyper-capitalism. To let readers understand Capital and Ideology dynamically, this study analyzes contents of this book from diverse angles in the context of the history of economy, political economics, or social science, including the perspectives of Joseph Schumpeter, Henry Chesbrough, Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Henry George, John Maynard Keynes, Karl Polanyi, Friedrich A. Hayek, Joseph Stiglitz, Robert Gordon, Walter Sheidel, Philippe Van Parijs, and Michael Sandel.

The author selected this book to answer the following research question, “How do we conquer the growth limits of capitalism?” By reading, and analyzing this book, the author obtained several clues on the way to conquer the growth limits of capitalism’s ideas in addition to his own future research agenda in open innovation dynamics. This study will provide a guide for readers to dynamically understand the vast and complex contents of Piketty’s book, and some clues for readers to consider about growth limits of capitalism.

2. About Historical Regimes of Inequality

Every human society must develop a range of contradictory discourses and ideologies for legitimizing the inequality that already exists or that people believe should exist. Without it, the whole political and social edifice risks collapse [1]. In his book, Piketty analyzed the advent of capital and the capitalist economy, and its evolution in human history, with the dynamics of inequality. Inequality evolving together with capital is neither economical nor technological, but ideological and political [1]. Therefore, the book relates to ideology directly, used in a positive and constructive sense to refer to a set of a priori and plausible ideas and discourses describing how a society should be structured [1].

The history of economic analysis and ideology is long. The Theory of Moral Sentiments, written by Adam Smith in 1759, can be regarded as the first book about economic or moral ideology. This theory was republished in his later book, The Wealth of Nations, in 1776, which has been accepted as containing the morals and ideology for economic agents, or markets, in capitalist economic systems [8]. According to Smith, everyone should control their self-love or intrinsic preferences until they receive the empathy of others, which could be taken as the ideological or moral basis of market function [1]. Karl Marx analyzed the capitalist economy’s ideological core from the perspective of transformation of money into capital; that is, from the production of absolute and relative surplus value to the accumulation of capital, the so-called primitive accumulation, in Capital Volume 1: A Critique of Political Economy [9]. Joseph Schumpeter also analyzed the evolution of capitalism into growing hostility and decomposition; he proposed the concept of socialism with democracy in his Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy as capitalism’s ideological destination [10]. Friedrich A. Hayek explained the absolute market ideology in his Law, Legislation and Liberty, and critiqued the ideology of the socialist planning economy in The Road to Serfdom [11,12].

Compared to these works of classical economics, Capital and Ideology has special value. It analyzes capitalism’s evolution with respect to the dynamic change of ownership ideology from ternary societies featuring trifunctional inequality to slave societies with extreme inequality, and colonial societies with diversity and domination, to the great 20th century transformations, such as social-democratic societies, communist and post-communist societies, and hyper-capitalism between modernity and archaism.

Inequality rebounded worldwide significantly between 1980 and 2018, including in Europe, China, Russia, the United States, and India. The top 10% of earners increased from 26–34% in 1980 to 34–56% in 2018 [1]. The top marginal tax rate applied to the highest average income was higher in 1900–1980 than in 1980–2018: from 1932 to 1980, it was 81% in the United States, 89% in the United Kingdom, 58% in Germany, and 60% in France [1]. Piketty explained the elephant curve of global inequality as those in the bottom 50% of the global income distribution experiencing substantial purchasing power growth between 1980 and 2018 of 60–120%. However, the lower and middle classes in wealthy countries, such as the United States’ white labor class, grew nearly 40% more slowly, and the top 1% captured 27% of all the growth during the same period. In summary, inequality decreased between the bottom and middle ranks of the income distribution and increased between the middle and top ranks, except for the top 1% [1]. This elephant curve appeared significantly in the United States from 1970 to the 2010s, and the curve was understood as the reason for the fall in American growth after the period 1920–1970 [13].

Before the appearance of the bourgeois society that flourished in 19th century France, trifunctional society was considered the ownership society archetype in a number of countries. A trifunctional social consisted of clergy as the religious and intellectual class, nobility as the military class, and a third class of workers (including peasants, artisans, and merchants) who provided food and clothing. This typology existed worldwide, from France, Spain, and the United Kingdom to European colonies, such as India and Iran [1]. Piketty differed from Schumpeter and Marx in that he accepted continuity from trifunctional societies to bourgeois society as the succession of inequality. He defined capitalism as a form of private property economy in which innovations are carried out by means of borrowed money, which, in general, though not by logical necessity, implies credit creation.

Schumpeter understood the situation before and after capitalism differently by treating the start of capitalism as the original accumulation of capital from credit creation [14]. If we understand that commodity circulation is capital’s starting point, we need to acknowledge that the modern history of capital begins from the 16th-century creation of world-embracing commerce, according to Marx [9]. As Marx treated the core of capitalist society as the conversion of surplus value, which is created by transforming labor into capital, society before and after capitalism differs markedly.

According to Piketty, the promotion of free labor was well under way before the Great Plague of 1347–1352 and the demographic slowdown of 1350–1450, occurring through productive cooperation in the trifunctional order, such as tithes, markets, and mills among workers (the true silent artisans of this labor revolution); ecclesiastical organizations; and lords [1]. This is different from the explanation of the Great Plague as the reason of the increase of free labor in West Europe, and the resurgence of serfdom in East Europe [15,16]. A more impressive point in the trifunctional order in Piketty’s formula is that the Christian Church was a property-owning organization unlike today’s non-profits, which have a relatively small share of all property, of between 1 and 6%: 1% in France, 3% in Japan, and 6% in the United States. This contrasts with the ancient regime in Europe when the church owned 10–35% of all property [1].

In addition, Piketty proposed that modern property originated from the Christian doctrine, which over centuries sought to secure the Church’s property rights and developed new financial technologies in defiance of old rules, for example, the sale of rents and various forms of debt-financed purchases [1]. Non-interference or a self-regulating market was not natural. If there are no interventions, a liberal market might not appear [17]. After the revolution, when ecclesiastical ownership was reduced to virtually nothing after Church property confiscation and tithe elimination, what was the property of the church and how and to whom did it belong in ownership societies?

The “Great Demarcation” of 1789 and the invention of modern property were seriously incomplete, according to Piketty, in that the primary objective was to transfer regional power from local noble and clerical elites to the central state, but not to organize a broad redistribution of wealth [1]. A progressive income tax system, or treatment of ownership inequality, would wait until 1914, because even though the radical Enlightenment group, such as Diderot, Condorcet, Holbach, and Paine, supported some form of property redistribution, moderate Enlightenment supporters like Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, and Smith were suspicious of the radical abolition of property rights, landlords, or slaveowners [1].

Piketty’s impressive findings are as follows: the ownership confirmation given to traditional landlords was strengthened by the proprietarian ideology’s sacralization, using religion as an explicit political ideology for ensuring social stability in the trifunctional order [1]. If social stability were the origin of the market sacralization in the capitalist economy according to neoclassical thought, a lot of things would not be bought. The limits of the market as a merit system in the highly unequal modern capitalist economy propose that market sacralization should be dissolved immediately [18,19].

Another one of Piketty’s impressive findings is that after the French Revolution of 1789, wealth inequality did not decrease, but rose rapidly in the Belle Epoque (1880–1914), and there seemed to be no limit to the concentration of fortunes until before World War I [1]. Even though the upper classes (referring to the wealthiest 10%) owned about 80–90% of the wealth in France, and today they own about 50–60%, those in the top 10% of income distribution claimed about 50% of the total income in the 19th century, compared with 30–35% today. The share of property-owning middle class, between the poorest 50% and the wealthiest 10%, in total wealth was less than 15% in the 19th century, but stands at about 40% today. The middle class’s income share was nearly 35% in the 19th century and stands at about 45% today [1]. However, the share of bottom 50% of society was very low in the 19th century and did not increase until recently. With respect to property, the share of the bottom 50% remained less than 10% from the 19th century until now; the income share of the class was 15% in the 19th century and is nearly 25% now.

In summary, a non-interference policy, or laissez-faire, has never been natural since the revolution, and market sacralization itself was the road to serfdom for the underclass in France during the 19th century, even though the underclass did not experience a decline in real income compared to the 20th century, when the French government intervened in the market [10,15]. Those with the largest fortunes even had a larger share of financial assets than the other wealthy. In 1912, the top 1% of Parisian fortunes consisted of 66% of financial assets, compared with 55% for the next 9%. This trend follows the growth of foreign financial investment between 1872 and 1912, with global capital expansion inside colonial societies. Perhaps the world’s capitalist system is based on the capital investment of the upper class of capitalist countries, such as France [20].

A progressive inheritance tax was implemented on 25 February 1901 in France; meanwhile, a progressive income tax was implemented in 1870 in Denmark, in 1887 in Japan, in 1891 in Prussia, in 1903 in Sweden, in 1909 in the United Kingdom, in 1913 in the United States, and in 1914 in France. This indicates that from the French Revolution until World War I, the inegalitarian evolution of the ownership society flourished in France, Europe, and the United States [1]. The extreme concentration of power and landed property in the English aristocracy is reflected by the fact that in 1880, nearly 80% of the land in the United Kingdom was owned by 7000 noble families (less than 0.1% of the population); this ratio was different from France in that on the eve of the revolution, the French nobility owned roughly 25–30% of French land [1]. The origin of the Speenhamland law, which supported any laborer who received income under the minimum basic level from 1795 to 1834, represented the concentration of landed property, a situation maintained until the end of the 19th century.

This was because rent, considered as the price paid for land use, was the highest that tenants could afford to pay under actual economic circumstances [15,21]. The gentry class, containing providential property owners and benefiting greatly from the prevailing regime, included the offspring of younger sons of peers, baronets, and knights as well as descendants of the old Anglo-Saxon feudal warrior class, according to Piketty. The third class in France had similar origins to the gentry class in the United Kingdom. In other words, ownership societies had their origins in the classic nobles of the trifunctional inequality, which Smith did not mention in his book. Marx, too, did not analyze the related transformation of the classic nobles into a bourgeoisie [21]. Even though the gentry class originated from the noble classes, they were different from the classic noble classes in the Senate, in that they passed progressive taxation and triggered the fall of the House of Lords. With progress in economic life through innovation motivating the divergence of wealth between the top and bottom classes in the United States, echoing 19th century patterns in the United Kingdom and France, Henry George proposed the general real estate tax system [22].

3. About Slave and Colonial Societies

The slavery system was abolished in the United Kingdom in the 18th century and its colonies in 1833–1843, France and its colonies in 1794–1848, the United States in 1865, and Brazil in 1888. However, the abolition of slavery did not bring about equality in the capitalist economy, and instead, compensation triggered extreme inequality, because no reparations were given to freed slaves. Instead, economic justification was given to compensating slaveholders for forced labor, proprietorial sacralization, and the question of reparations, according to Piketty [1]. In other words, slavery’s abolishment led to the development of a capitalist economy by creating new workers, who had been the slaves, and provided the chance for slave owners to accumulate capital by compensation. Using modest or average family taxpayer money, the British government paid slaveholders an indemnity roughly equal to the market value of their slave stocks. During 1825–1950, Haiti paid 150 million gold francs to compensate French slaveowners. In the United States, even though providing compensation for slaveowners was impossible owing to the high national debt at that time in northern regions and because the vast majority of southern slave owners were in revolt, social nativism—in other words, social racialism, or discrimination against ex-slaves—was maintained until the 1960s and even today. In Brazil, even though slavery wars ended in 1888, extreme inequality remained until 1980 because of wealth qualification, which was used to decide whether illiterate people would vote or not [1,19].

Until recently, colonial society demonstrated maximal inequality in terms of property and income, as the colonial powers’ mechanisms of financial and military coercion extended the accumulation process in colonies. Indeed, slave and colonial societies have left indelible traces on the structure of modern inequality, both among countries and within them [1]. In fact, several colonial societies that experienced the second colonial age, from 1800–1850 until 1960, are in poor economic condition even now because they have experienced deficient effective demand. If there is no change in the propensity to consume because of extreme inequality, employment cannot be increased [23].

According to Piketty’s examination of extreme inequality in colonial societies, the top 10% of earners received more than 80% of the total income in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1780; 70% in colonial Algeria in 1930; more than 70% in South Africa in 1950; and 60% in Reunion. However, the rate in France was at 50% in 1910 and 35% in 2018 [1]. In addition, Piketty proved that the significantly high levels of inequality in the slave and colonial societies were constructed around specific political and ideological projects, relying on specific power relations and legal and institutional systems. In terms of colonization, the colonial budgets were paid mainly to colonizers. These budgets recorded separately the salaries paid to civil servants from the metropole and those recruited from the indigenous population. In Algeria in 1950, the most favored 10% (the colonizers) received 82% of the total educational expenditure; the comparable figure for France was 38% in 1910 and 20% in 2018. Whites in South Africa still represented more than 85% of the top 10% of the population by wealth, although they accounted for a little more than 10% of the total population, until the 2010s [1].

Piketty showed the connection between the colonial experience or heritage and the poor 21st century economic trajectories of India and Eurasia. Under the auspices of the East India Company’s shareholders from 1757 to 1858, and under the authority of the Empire of India from 1858 to 1947, the British fit complex professional and cultural identities into the rigid framework of the four varnas (people grouped according to their professions), which led to a number of the essential features of today’s India. The administrative categories created by the British to rule the country and assign rights and duties frequently bore little relation to actual social identities based on the policy of assigning identities. They profoundly disrupted the existing social structures and, in many cases, solidified the once-flexible boundaries between groups, thus fostering new antagonisms and tensions [1].

Piketty found several pieces of evidence for this. First, Indian society encompassed thousands of social micro-classes and professional guilds, and the political and social order was constantly being challenged through revolts by the dominant classes and by the regular appearance of new warrior classes bearing new promises of harmony, justice, and stability [1].

Second, as the Kshatriyas were treated as having a higher social status than the Brahmins, Brahmin prestige and preeminence as intellectual elites sometimes superseded limits imposed on them by the Kshatriyas. In fulfilling religious and education functions, they went so far as to validate and enforce judgments concerning dietary or familial laws relating to temple access, water, and schools and, in some cases, even imposing ex-communication [1]. Third, even though the small group of Kayasthas, which accounted for about 1% of the population (more than 2% in Bengal), had an intellectual and educational capital that equaled or sometimes surpassed that of the Brahmins, it was impossible for them to be treated as either Brahmins or Kshatriyas by the British [1]. Piketty concluded that colonial India, with its rigidification of castes, let independent India continue to face historical status inequalities through property and status inequity and even social and gender quotas.

Piketty believed the reason for the great divergence between Asia and Europe stemmed from the high rivalries among European states during the 17th and 18th centuries in the development of unprecedented levels of fiscal and military capacity, which was beyond the capacities of the Chinese and Ottoman empires. His first piece of evidence was that tax receipts stagnated at 1–2% of the national income in the Chinese and Ottoman empires but rose to 8–10% in 18th–19th century Europe. Second, interstate competition motivated technological and financial innovations in Europe until the European states experienced the industrial revolution, in contrast with their Asian competitors. Third, the colonial dominance of India, Indochina, China, and America let the European countries develop a system dynamic feedback loop among technological and financial innovation and increase military and tax income through economic exploitation of the colonies [1].

The maturing of European states in the 18th and 19th centuries is opposite to the ideal of Smith’s capitalism, because economic growth in this period was not motivated by the market, but rather by the state’s intervention in innovation and the colonial intervention in the state economy, such as in India and China [21]. Polanyi stated that the European industrial revolution resulted not from market operations, but from the European states competing against each other. China in the 18th and 19th centuries was close to the ideal state defined by Smith in terms of economic liberalism, low taxes, balanced budgets (with little or no public debt), absolute respect for property rights, and markets for labor and goods that were as integrated and competitive as possible. Market self-regulation, which was expressed as an unseen hand, was a complete myth or a fanciful invention [1].

4. About the Great 20th Century Transformation

Piketty pointed out that the 1914–1945 period saw the collapse of inequality and private property. Similar to Polanyi, he called this the “Great Transformation.” First, the top decile’s share of the total national income, which averaged around 50% in Western Europe in 1900–1910, went down to around 30% in 1950–1980 after the collapse of private property during 1914–1945. Second, the market value of private property (real estate, professional and financial assets, net of debt), which was close to 6–8 years of national income in Western Europe from 1870 to 1940, collapsed during 1914–1950, and stabilized at 2–3 years of national income in 1950–1970, resulting from a serious decline of private property during 1941–1950 owing to such factors as expropriation and nationalization, policies aimed at reducing private property value and the power of property owners, low levels of private investment and returns, and high inflation during this period. Third, the exceptional taxes that were generally applied to private assets of all types, including buildings, land, and professional and financial assets, afforded great latitude for distributing burdens partly because the rate could vary with the amount of wealth (usually with an exemption for the smallest fortunes, with rates to the extent of 5–10% for medium-sized fortunes and 30–50% or more for the largest fortunes). Fourth, the highly progressive taxation for the top income segment motivated moving from declining wealth to durable decentralization. The top marginal rate applicable to the highest US incomes was 23% on average in 1900–1932, 81% from 1932 to 1980, and 39% from 1980 to 2018. In these same periods, the top rates were 30%, 89%, and 46% in the United Kingdom; 26%, 68%, and 53% in Japan; 18%, 58%, and 50% in Germany; and 23%, 60%, and 57% in France. In the same period, the highest inheritance tax was 12%, 75%, and 50% in the United States; 25%, 72%, and 46% in the United Kingdom; 9%, 64%, and 63% in Japan; 8%, 23%, and 32% in Germany; and 15%, 22%, and 39% in France.

Fifth, the rise of the fiscal and social state (total tax receipts in rich countries amounted to less than 10% until World War I before rising sharply from 1910 to 1980 and then stabilizing at around 30% in the United States, 40% in the United Kingdom, and 45–55% in Germany, France, and Sweden, respectively) played a central role in the transformation of ownership societies into social-democratic societies in which governments pay for the army, police, justice, administration, education (primary, secondary, and higher), pensions and disability, health (health insurance, hospitals, etc.), social transfers (family, unemployment, etc.), and other social expenditures [1]. Piketty related the reason for the world economy’s fast growth during 1940–1980 to the collapse of inequality. However, Gordon attributed the reason for the great leap forward by the United States in 1920–1950 to World War II itself and great inventions, such as electronics and the internal combustion engine; the increase of labor income; and the decrease of labor hours [13]. The dramatic decrease of inequality during 1914–1950 in the United States was the result of political choices, such as the New Deal Policies of President Franklin Roosevelt, which were opposite to the pursuit of inequality by the Reagan administration in the United States, or the Thatcher administration in the United Kingdom [24]. Even though it seems that there are conflicts between removing inequality and efficiency or economic growth, the pursuit of inequality with the logic of equality of opportunity again arrives at higher inequality, according to the evolution of European and US economies during 1914–1950 and after the 1980s [19,24,25].

Piketty found that the social-democratic societies of capitalist countries between 1950 and 1980, with a mixture of policies, including nationalization, public education, health and pension reforms, and progressive taxation of the highest incomes and the largest fortunes, created incomplete equality. I summarize his reasons as follows. Social-democratic societies began to run into trouble in the 1980s, and the top decile’s share of wealth increased in all parts of the world, from 27–34% in 1980 to 34–56% in 2018. The share of the bottom 50% decreased from 20–27% in 1980 to 1–12% in 2018. The divergence of top and bottom is greater in India and the United States than in China and Europe [1].

First, the social ownership that institutionalized power sharing between workers and shareholders in Germany and Nordic Europe (especially Austria, Denmark, and Norway) has several limits: corporate limits, such as firms having more than 500 employees in Germany, more than 25 employees in Sweden, and more than 35 employees and 50 employees in Denmark and Norway, respectively; limitations of co-management and labor participation on oversight committees; the slow diffusion of German and Nordic co-management to the United Kingdom and France by insisting on nationalization and social security; a bargain-basement social democracy through the New Deal of the United States, such as no universal health insurance, less generous pensions, and unemployment insurance; and no evidence of co-management, which were discussed by the Democratic Party and Republican Parties together in 2018 [1].

Second, social democracy has no good answer to how to provide equal access to education and knowledge, particularly higher education, with a fall of the bottom 50% share in the United States from 1960 to 2015 because of an unprecedented increase in very high incomes, especially the famous “1%” since 1980. The probability of attending university in the mid-2010s was 20–30% for the children of the poorest parents, increasing almost linearly to 90% for the children of the richest parents in the United States. The private financing of higher education is extremely different across countries, at 60–70% in the United States and nearly 60% in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, compared with an average of 30% in France, Italy, and Spain and less than 10% in Germany, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. Public spending on education, which increased rapidly in the 20th century from barely 1–2% of the national income in 1870–1910 to 5–6% in 1980, subsequently stagnated between 1990 and 2015 at about 5.5–6% of the national income [1]. In other words, the tyranny of merit in higher education in the United States as well as in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia is not fair and is becoming an engine of heightened inequality [13,19].

Third, strongly progressive taxes are clearly no obstacle to rapid productivity growth, based on evidence that growth was the highest in 1950–1990 when inequality was lower and fiscal progressivity greater in Europe and the United States. Yet, the tax system of social democracy has missed many opportunities, including the failure to set up any kind of common fiscal policy to respond to the liberalization of capital flows without fiscal dumping, or to build a progressive wealth tax system in addition to progressive income and inheritance taxes [1].

Piketty pointed out creative factors that triggered the collapse of Soviet communism and Russia’s oligarchic and kleptocratic turn. First, even though Soviet communism was based on the complete elimination of private property and its replacement by comprehensive state ownership, it did not have any proper theory of property, such as, “How would the new relations of production and property be organized? What would be done about the small production units and about the commercial, transport, and agricultural sectors? How would decisions be made and how would wealth be distributed by the gigantic state planning apparatus?” [1,2]. In other words, the contents and processes of the capitalist civilization did not prepare for running without the proletarian dictatorship through the nation before the ban on private ownership [10,26].

Between 1950 and 1990, even though the total ban on private property reduced the share of the top decile in the total national income to 25% on average in Soviet Russia, which was lower than in Western Europe and the United States, before rising to 45–50% after the fall of communism, Russia’s per capita income stabilized at only 60% of the Western European level [1]. Even before moral prestige issues such as decolonization, antiracism, and racial equality, and feminism disappeared in 1970, Soviet Russia failed to set up any reflective private property system with a decentralized social organization to go with a progressive wealth tax, a universal capital endowment, and power sharing between stockholders and employees. In addition, Soviet Russia did not establish any private ownership systems, such as those developed in northern Europe, when it returned to capitalism through its “Shock Therapy.” The post-communist regime abandoned not only any ambition to redistribute property but also any effort to record income or wealth—for example, no inheritance tax and an income tax strictly proportional at only 13%. Financial assets held in the tax havens of Russia amount to nearly 50% [1]. According to Piketty, capitalist Russia does not show any evidence that it is placed higher than 60% of Europe or the United States in income, as maintained from 1950 to 1990 by communist Russia. Piketty’s criticism is understandable in that a social-democratic ownership system with several decentralized subsystems should be considered more seriously than “Shock Therapy,” which is damaging the Russian economy even now.

Piketty found it impressive that China is growing at high speed with a mixed economy based on a dignified balance between private and public property, which has proved to be durable under the leading role of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and has been maintained and reinforced in recent years [1]. First, China’s public capital ratio to private capital decreased from 70% of the total in 1978 to stabilize at nearly 30% in 2006, and was maintained until 2018. This ratio was at 15–30% in capitalist countries in the 1970s and near zero or negative in the late 2010s [1]. Second, even though China introduced a 30% (and roughly 40%, if profits from public firms and sale of public land are included) progressive income tax system with marginal rates ranging from 5% for the lowest income brackets to 45% for the highest, income inequality increased sharply in China during 1980–2018; however, it remains below that of the United States but higher than that of Europe [1].

Third, China has several issues that must be addressed with reforms, according to Piketty. Although China does not have an inheritance tax, it is expected to develop new forms of progressive income, inheritance, and wealth taxes in the near future to reduce inequality. Intriguingly, inequality had decreased dramatically in China as an effect of the Cultural Revolution with respect to the perception of inequality. Even though the CCP partially constructed norms of socioeconomic justice through Chinese-style party-managed democracy, there are good reasons to ponder the merits of granting more substantial constitutional protections for social rights, educational justice, and fiscal progressivity [1,27]. The fact that income inequality is lower in the former communist countries of Eastern Europe than in the United States or post-Soviet Russia can be attributed to the relatively highly developed egalitarian systems of education and social protection inherited from the communist period; the transition from communism proceeded more gradually and in a less inegalitarian fashion in these countries than in Russia. However, the tendency of dominant economic actors to “naturalize” market forces and the resulting inequalities is now common in Eastern Europe [1,28].

Piketty pointed out that the neo-proprietarianism that emerged in the 1990s has remained until now in the 21st century with opacity of wealth, fiscal competition for tax decreases, persistence of hyper-concentrated wealth, a new monetary regime, and the invention of meritocracy. First, inequality in the 21st century has appeared as a great divide. The top decile’s share in total income in 2018 was 64% in the Middle East compared with 9% for the bottom 50%. In Europe, the ratios are 34%, and 21%, respectively, and in the United States, 47% and 13%, respectively. The extreme inequality has heightened tensions and contributed to persistent instability in several regions, such as the Middle East, Europe, and the United States [1,24,29].

Second, the increase in the total value of private property often reflects an increase in the power of private capital as a social institution and not in the “the capital of market” in the broadest sense with a dramatic increase of private appropriation of common knowledge in the 21st century, as manifest in the rise of Apple, Google, and Tesla [1,30,31].

Third, statistical agencies, tax authorities, and political leaders have failed to recognize the degree to which financial portfolios have been internationalized and promoted the free circulation of capital without a common system of registration or taxation of property. They have not developed the tools needed to assess the distribution of wealth and to follow its evolution over time, like a public financial register; the top decile’s share of total private wealth (real estate, professional and financial assets, net of debt) has increased sharply in the United States (up to 75%), Russia (up to 71%), China (up to 65%), India (up to 62%), France (up to 55%), and the United Kingdom (52%). The lack of economic and financial transparency mean that assets held in tax havens represent at least 30% of total African financial assets, triple that of Europe [1].

Fourth, with the new role of central banks in creating money since the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s major central banks devised increasingly complex money-creation schemes collectively described by the enigmatic term “quantitative easing” together with the financialization of the economy [1,30]. This is different from Keynes’ perspective because he backed fiscal policies, and emphasized the importance of traditional monetary policy only in a liquidity trap; in addition, he never evaluated unconventional policies of the type used in the global financial crisis.

As the marginal efficiency of capital in equilibrium is down to approximately zero, we should attain the conditions of a quasi-stationary community in which change and progress would result only from changes in technique, taste, population, and institutions, with the products of capital selling at a price proportional to that of labor [23]. Fifth, the neo-proprietarian ideology relies on order-liberalism and meritocracy, including the “pandorian” refusal to redistribute wealth (especially a progressive tax), and the free circulation of capital without regulation, information sharing, or a common tax system based on social justice [9,10]. Meritocratic discourse on educational injustice in the United States, Europe, and South Korea cannot glorify the winners in the economic system while stigmatizing the losers based on lack of merit, virtue, or diligence, because we must agree that meritocracy is based on inequality of education [1,8,18,19].

5. About Rethinking the Dimensions of Political Conflicts

According to Piketty, the structure of political conflict changed historically from the classical dimension, in the sense that in the period 1950–1980, it pitted less advantaged social classes against more advantaged social classes, regardless of the axis, to become a system of multiple elites based on wealth, education, or income in the period 1990–2020. Classist electoral conflict had at least mobilized all social categories in equal proportions in terms of redistribution, welfare state, social insurance, and progressive taxation during 1950–1980. As an electoral regime of competing elites in 1990–2020 placed social cleavage at the center of political conflict, the debate about redistribution was largely obliterated and the less advantaged classes substantially reduced their participation [1].

First, according to Piketty’s analysis of France, in the post-war years, people who voted left were likely to be less well-educated salaried workers, whereas in the 21st century, people with higher levels of education tended to vote left [1]. Second, the voter turnout ratio of the bottom 50%, not the upper 50%, increased by 10–12% in the 2010s, compared to 2–3% during 1950–1970. In other words, less educated blue-collar workers who voted strongly for the left in the 1950s and 1960s ceased to do so in 1990–2020 because they began to feel increasingly abandoned by these parties, which increasingly drew support from other social groups whose members were notably more highly educated [1]. It is possible that the electorate was divided four ways according to borders and factors into egalitarian internationalists, inegalitarian internationalists, inegalitarian nativists, or egalitarian nativists; this situation is clearly aggravating inequality in the 21st century capitalist economy. The importance of relocating the political economy approach in analyzing the capitalist macro economy by Piketty along with Smith, Marx, George, Schumpeter, Keynes, and Polanyi should not be underestimated [22,23].

According to Piketty, in the United States and the United Kingdom, a transformation of the party system can be seen, similar to that in France, but to a lesser extent than in the United Kingdom. For example, although in 1948 the US Democratic candidate, Truman, won 26% of the vote of those with advanced degrees, the Democratic candidate in 2016, Clinton, won 45% of the vote of those with high school diplomas and 75% of the vote of those with a doctorate [1]. Although the Labour Party of the United Kingdom in 1955 scored 26 points lower among those with college degrees than those without, it scored 6 points higher among those with college degrees than those without degrees [1]. Party system transformation is now exaggerating inequality in both the United States and the United Kingdom. In the United States, the “Brahmin Left,” which is what the Democratic Party had become by 1990–2010, shared common interests with the “merchant right” that had ruled under Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush; in other words, the Clinton and Obama administrations maintained the reduction of progressive income taxes and the de-indexing of the federal minimum wage even though, in the 2020 presidential campaign, several Democratic Party candidates proposed restoring the progressivity of income and inheritance taxes and creating a federal wealth tax [1]. In the United Kingdom, although Keynes worried about the lack of Labour Party intellectuals, and Hayek about the party’s authoritarian rule and trampling of individual liberties, it now had support from a majority of intellectuals. Thus, both the Labour Party and the Democratic Party support the high-income class in protecting its own wealth and income [12,32]. In the 2016 Brexit referendum, the top income, education, and wealth deciles voted strongly to “remain” while the lower deciles voted to “leave”; in the internationalist versus nativist dimension, nativists won in the United Kingdom, as has been the case in France [1].

According to Piketty, the recent rise of social and market nativism in some nations in the postcolonial era has become another engine to exaggerate inequality in the capitalist economy system [1]. Piketty’s findings on the concrete positive relationship between social nativism and the highly rising inequality in the world capitalist economy is one of his creative research outputs that political economy scholars should support. First, in the period 1950–1970, the vote for Democrats in the United States and for various left parties in Europe was higher among less educated voters; in 2000–2020, it was higher among more educated voters. This trend is also evident in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Italy, Canada, Australia, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, albeit with some time lags [1].

Second, diversity exists in the rise of social nativism, evident in Europe, from the redistributive social and fiscal measures offered with an intransigent defense of Polish national identity by the PiC (Law and Justice) party, to the guaranteed minimum income and uncompromising anti-refugee stance championed by Italian parties M5S and Lega. However, there is no concrete difference in the market-nativist ideology, according to the M5S acceptance of Lega’s “flat tax” or Donald Trump’s polices, such as tax cuts for the rich and multinational corporations, because social nativism is highly likely to lead to a market-nativist type of ideology [1].

Third, Piketty proposed the possibility of social federalism in Europe as an alternative to social nativism, with the construction of a transnational democratic space through the European Assembly’s approval of four important common taxes: corporate profits, high incomes, large fortunes, and carbon emissions. Piketty pointed out that “in the absence of such accords, the risk is that the race to the bottom will continue, fiscal dumping will increase, inequality will continue to rise, and xenophobic, identarian, anti-immigrant political parties will continue to exploit the situation in their pursuit of power” [1].

Fourth, according to Piketty, the Indian ruling BJP and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro also fell into the social-nativism trap, which lies far from motivating for redistribution or decreasing inequality [1,2]. Piketty used capitalism and socialism to explain property accumulation, and democracy to explain borders and nativism, to highlight the political economics of the inequality of modern capitalism, similarly to Schumpeter, who used capitalism, socialism, and democracy to explain the early 20th century’s capitalist economy [10].

Piketty proposed several ideas as elements for a 21st century participatory socialism, as follows: (1) sharing power in firms by capital and labor, progressive wealth taxes, and circulation of capital, universal capital endowment, basic income and just wage, and the progressive tax triptych of property, inheritance, and income with institutionalization at the constitutional level; (2) social federalism with a public financial register at the international level; (3) progressive taxation of carbon emissions for individual consumers; (4) allocation of additional resources to improve educational opportunities for all, especially young people from disadvantaged classes; (5) democratic equality vouchers to substitute the tax-refund-political-donation system toward a participatory and egalitarian democracy; and (6) a transnational democratic assembly as a new global congressional organization with responsibility for decision-making concerning global public goods or global fiscal justice [1]. The idea of “progressive wealth taxes” proposed by Piketty as the central tool for achieving true circulation of capital and as the source of a universal capital endowment to be given to each young adult at age 25 years is very creative [1]. This is not a progressive inheritance tax, but rather a progressive annual tax on wealth considering the human life span, which has continued to lengthen. The possibility of enacting this tax in the United States and of a progressive European wealth tax to fund the European COVID-19 response are being discussed by the US, and Europe [33,34].

Piketty proposed a highly attractive “public financial register” system as a method to foster a form of global social federalism because, ideally, the return to social progressivity and the implementation of a progressive property tax should take place in as broad an international setting as possible. Much of the United States’ taxes or the French wealth tax (ISF) can be thought of as the roots of “a public financial register” that does not allow all classes, especially the wealthy class, to escape taxation by moving wealth to other less progressive tax jurisdictions. According to Piketty, wealth transparency based on a public financial register would make it possible to establish a uniform progressive tax on property while sharply decreasing taxes on people of modest wealth or those without property, and increasing taxes on those already possessing significant wealth [1].

6. Discussion

6.1. The Difference of Inequality Logics among Tomas Piketty, Joseph Stiglitz, and Anthony Atkinson

Piketty pointed out the source of inequality of capitalism from the essential factor capitalism “r > g”. He proved this in Capital in 21st Century, and The Economics of Inequality with statistical evidences mainly from capitalist histories of Europe, and the United States. He also analyzed the contexts of political economy and ideology which are embedded in the capitalism rule “r > g” in the former book.

However, Joseph Stiglitz pointed out the functional income distribution which triggered the inequality when he explained ‘the price of inequality’, and ‘the great divide’. So, for him, inequality could be conquered by public policy such as controlling rent seeking, or increasing the power of labor unions as balancing the power of capital.

By the way, Anthony Atkinson, who was the mentor of Thomas Piketty, measured poverty by the Atkinson Index, and found the sources of inequality from diverse public policies including the design of the tax structure such as the ratio of direct versus indirect taxation [35,36]. He proposed diverse ideas which can be used to conquer inequality such as sharing of capital, social welfare, national intervention in technological progress, and income share revision, etc., in addition to progressive taxes [37,38].

6.2. The Critic on Piketty, and the Answer in this Book

Devesh Raval and a lot of new classical economists have pointed out that ‘r > g’ means that in the process of accumulation of capital, the productivity of marginal capital could be maintained. He also criticized the idea that the productivity of marginal capital should be decreased with the accumulation of capital. Piketty in his book showed and explained ‘r > g’ in the history of capitalism with the dynamic and diverse ideologies which defended ‘r > g’ [27]. Robert Solo called ‘r > g’ the ‘rich-get-richer dynamics’ and accepted it as right, proposing evidence such as: (1) the real decrease of minimum income, (2) the corruption of labor unions, (3) the decrease of life expectancy of low-income labor classes in poor countries, (4) technological innovation and the decrease of middle-class jobs, (5) the increasing divide between upper labor and low labor class, etc. [6].

6.3. Causal Loop Modeling of Piketty’s Findings and a Future Research Agenda on Open Innovation Dynamics

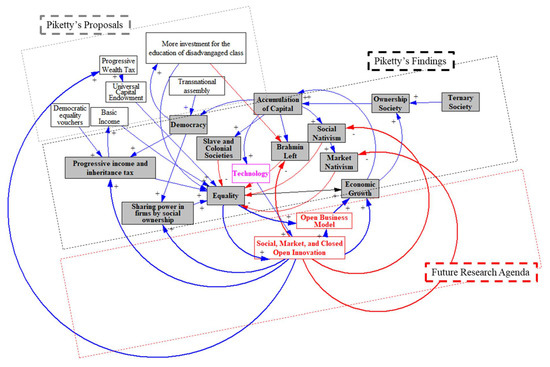

Piketty analyzed the history of the capitalist economy from the trifunctional inequality economy to the hyper-capitalist economy of the 21st century. The development can be represented by logical causal models, depicted as gray rectangles in Figure 1, which shows the concept modeling of the results of this review.

Figure 1.

Causal loop modeling of Piketty’s findings and proposals for future research on open innovation dynamics. Additional explanation: Grey colors are Piketty’s proposals; Black colors are Piketty’s findings; Red colors are ‘future research agenda’; “+” means positive feedback; “-” means negative feedback.

First, when trifunctional inequality was transformed to ownership societies, the market acted as the clergy, defending ownership inequality, such as free labor of the producing class, by sanctification of the market. In other words, in trifunctional society, ownership inequality was confirmed by the religion as the blessing of God by the clergy itself. However, in a capital economy society, ownership inequality was confirmed by the sanctification of the market through the natural balance between consumption and providing.

The sanctification of the market helped maintain the inequality of wealth during the French Revolution and the liberation of slaves. Piketty explained his findings and proposals by using statistical data and concrete global evidence that the accumulation of capital motivated democracy and triggers progressive income, inheritance tax, and sharing of power in firms by social ownership, which increased equality and led to high economic growth in 1940–1980 (“Piketty’s findings” in Figure 1). However, the accumulation of capital triggered the Brahmin Left, social nativism, or market nativism, which motivated inequality and left the global economy in a low-growth trap.

Second, Piketty asserted a positive causal relationship between the equality in economic ownership and economic growth rates in several nations in global capitalist economic history, which is opposite to the perspective of classical economics. However, these assertations require additional research on the mechanism involved from equality to economic growth from the microeconomic perspective. My own research papers, “Social, Market, and Closed Open Innovation” and “Open Business Model,” were inspired by the equality of wealth motivating economic growth [4,39,40,41,42]. Additional research on the role of open innovation and the open business model between equality and economic growth are required to generalize concrete results, which will be the future research agenda.

Third, Piketty proposed several creative and attractive policy mechanism designs for motivating equality in a capitalist economy to conquer the growth limits of capitalism, such as a progressive wealth tax or a kind of inheritance tax, universal capital endowment for youth under 25 years of age, basic income from budgets or increased progressive income, a transnational assembly to control the flow of capital, maintenance of a public financial register, democratic equality vouchers to separate democracy from wealth, and more investment for the education of the disadvantaged class, which would stop the rise of the Brahmin Left. These recommendations are based on Piketty’s findings on the evolution of the global capitalist economy. He not only identified these policies, which had existed in history, but also proposed innovative policies to conquer 21st century hyper-capitalist inequality.

Fourth, by reviewing this book, the author could discover his own research agenda on open innovation dynamics, as shown in Figure 1. I found partial evidence in my last field of research for the reinforcing role of “social, market, and closed open innovation” in motivating “sharing power in firms by social ownership,” “progressive income and inheritance tax,” and “progressive wealth tax.” In addition, the review enabled me to establish a balancing or negative effect of “social, market, and closed open innovation” and the “open business model” on the “Brahmin Left,” “market nativism,” and “social nativism,” for which I had substantial evidence from my own research [43,44,45,46].

Equality could motivate social open innovation in addition to market open innovation in the short term. Increased social open innovation, and market open innovation also could motivate new business models which would trigger economic growth. These in the long term could motivate closed open innovation of big businesses. In addition, the increase of equality can have an effect on the increasing demand for power sharing. While the future research agenda is not fixed and confirmed, it should be expanded to find ways to conquer the growth limits of capitalism.

Funding

This work was supported by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministyr of Science and ICT (22-IT-10-02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Piketty, T. Capital and Ideology; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1, 3, 7, 21, 25, 32, 68, 91, 92, 117, 121, 124, 127, 148, 151, 156, 164, 165, 203, 208, 209, 210, 217, 245, 248, 260, 261, 264, 269, 273, 274, 287, 296, 298, 307, 317, 312, 324, 339, 341, 362, 366, 368, 372, 374, 416, 420, 430, 432, 433, 448, 449, 457, 486, 492, 490, 498, 524, 535–537, 541, 543, 549, 550, 559, 578, 579, 584, 586, 592, 594, 596, 602, 606, 607, 618, 620, 621, 623, 625, 631, 634, 637, 642, 651, 657, 670, 671, 674, 679, 695, 696, 698, 712, 722, 723, 725, 742, 743, 751, 753, 809, 841, 838, 859, 864, 867, 874, 879, 886, 888, 892, 894, 898, 919, 959, 975, 979, 991, 992, 994. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J. How do we conquer the growth limits of capitalism? Schumpeterian dynamics of open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2015, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.J.; Liu, Z. Micro-and macro-dynamics of open innovation with a quadruple-helix model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K. Entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation. J. Evol. Econ. 2018, 28, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boushey, H.; DeLong, J.B.; Steinbaum, M. After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 70, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T.; Goldhammer, A. The Economics of Inequality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The Theory of Moral Sentiments; Penguin: London, UK, 1759. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital: Volume I; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942; pp. 12, 705, 707. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F.A. Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 1: Rules and Order; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F.A. The Road to Serfdom: Text and Documents: The Definitive Edition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living since the Civil War; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017; p. 757. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill Book Company: London, UK, 1939; Volume I–II, pp. 223, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, R. Agrarian class structure and economic development in pre-industrial Europe. Past Present JSTOR 1976, 70, 30–75, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. Tenure and the land market in early modern England: Or a late contribution to the Brenner debate. Econ. Hist. Rev. 1990, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1944; p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. In Tanner Lectures on Human Values 21; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 87–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? Allen Lane: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, I. The rise and future demise of the world capitalist system: Concepts for comparative analysis. In Introduction to the Sociology of “Developing Societies”; Alavi, H., Shanon, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The Wealth of Nations; Originally published March, 1776; Simon & Brown: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- George, H. Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions, and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth; The Remedy; Appleton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1880; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1935; pp. 14, 17, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidel, W. The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-first Century; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. The Great Divide; Penguin: London, UK, 2015; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Renan, E. What is a Nation? Originally, it was published on 1882; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, E. Red Star over China: The Classic Account of the Birth of Chinese Communism; Atlantic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski, P. Naturalizing the market on the road to revisionism: Bruce Caldwell’s Hayek’s challenge and the challenge of Hayek interpretation. J. Inst. Econ. 2007, 3, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers our Future; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy; Hachette: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. The Entrepreneurial State; Demos: London, UK, 2011; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. Am I a Liberal? In Essays in Persuasion; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landais, C.; Saez, E.; Zucman, G.J.V. A Progressive European WEALTH tax to Fund the European COVID Response. VoxEU 2020, 113–118. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/progressive-european-wealth-tax-fund-european-covid-response (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Saez, E.; Zucman, G. Progressive wealth taxation. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act. 2019, 2019, 437–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B. On the measurement of poverty. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1987, 55, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B.; Stiglitz, J.E. The design of tax structure: Direct versus indirect taxation. J. Public Econ. 1976, 6, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B. Inequality. In Inequality; Harvard University Press: Cambrige, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, A.B. After piketty? Br. J. Sociol. 2014, 65, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.J.; Egbetoku, A.A.; Zhao, X.J.S. How does a social open innovation succeed? Learning from Burro battery and grassroots innovation festival of India. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2019, 24, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Jeong, E.; Zhao, X.; Hahm, S.D.; Kim, K. Collective intelligence: An emerging world in open innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.; Hahm, S.D.; Kim, D. Basic income with high open innovation dynamics: The way to the entrepreneurial state. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Jeong, E.; Park, K.; Yang, J.; Park, J.J.T.F.; Change, S. The relationship between technology, business model, and market in autonomous car and intelligent robot industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 103, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation Results: Going Beyond the Hype and Getting Down to Business; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).