1. Introduction

This paper introduces and analyses the persuasive supply chain (PSC) of contemporary digital capitalism. This is a form of open innovation that is seldom anatomised, since it mainly addresses the cognitive–cultural sphere [

1]. of what, elsewhere, is referred to as the attention economy [

2]. It will be shown that persuasiveness is the narcissistic impulse of consumer desire that now drives the market for human consumption goods and services. In a post-industrial epoch that has displaced production from the economic core, advanced market economies increasingly rely upon branding, celebrity, and digital clickbait to stimulate demand in this consumption-led era. In the following sub-section, we will craft a model to connect relevant cognitive elements in the PSC. Each of these fills out interaction links in the complex PSC supply chain. The model is non-linear, meaning that each element has its opposite or variant. In occupational psychology, on which this approach draws, pattern recognition involves contrasts such as “dark” versus “light” personality traits [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In our model, non-linear relations between elements such as ‘narcissism’ and ‘reserve’ or ‘desire’ and ‘vanity’ enter the picture. These play roles as opposites but also as complementarities or inferentials. The originality of this representation of the transference of focus is that it moves analysis from the psychic level to the social economy [

1] and the collective level of ‘city branding’. This means the city is the object of ‘celebrification’, notably when it displays innovativeness, particularly in adopting contrarian attitudes to dominant socio-cultural, political or economic fashions.

Subsequently, we explain the sequence of steps we took to investigate the cognitive-cultural process that underlies cultural change processes within what has come to be called ‘city branding’. This is a prelude to explaining how our performative PSC model works. These steps develop in the succeeding narrative and discourse on the empirical cases of interest. We perform, first, an analysis of the role of digital media in city branding; second, the nature of human psychological traits that are magnified when using digital media; and third, an analysis of the efforts to induce social change from ‘darker’ to ‘lighter’ forms of ‘city branding’. Thus, for example, the particular branding of “Made in Italy” is a globally recognised symbol of high-quality fashion clothing design. This has also led to the rebranding of cities with close links to modern fashion, even transforming the reputation of a classical Renaissance “Art City” into a more modern “Fashion City” in the case of Florence. However, at the contrarian end of the cognitive-cultural spectrum, “Pronto Moda” (quick or “fast fashion”) [

8], which also originated in Tuscany as “Made in Italy”, is currently considered a form of “dark” branding. As we show later, this deformation occurred as digitization was deployed to compete through the fast-fashion supply chain against cheaper, imitative fashion replicas from India and China. Consequently, thousands of Chinese workshops were established in Tuscan towns such as Prato and Carpi to develop the “Made in Italy” brand [

7]. Therefore, what began as a “light” brand quickly became a “dark”, unsustainable brand and practice. We show in the next section how this is an effect of “learning”, whereby narcissism of the kind associated with benign imitation can evolve, possibly unintentionally, through celebrification into a process of mimesis, with malign outcomes [

9].

The parallel with social media firms, such as Google and Facebook, that were once deemed “light” brands in the early days of digital innovation but are now consistently seen as “dark”, is striking. They have become “dark” symbols of the digital communication era due to their imperiousness, insouciance, and multifold infractions against standard social norms and values. Our second evolutionary experience of cognitive–cultural stimulus pursues the case of Lisbon’s “green” sustainable city strategy. This has involved exploiting the name and reputation of the once globally revered pop star, Madonna. She moved to the city to live there, has adopted and promoted the city’s culture extensively through social media, and was highlighted in a series of performances to unite her pop-icon image with her recent absorption into the sustainability discourse as Lisbon’s “green influencer”. Our last vignette ends with recent accounts of the emergence in a post-coronavirus era of a narrative attempting to re-brand the “Ghost City” image with which many global cities are now struggling as workers and residents transform their living, working, and mobility [

6]. These are trends that were long-visible in the post-industrial after-effects of de-industrialisation in older manufacturing towns and cities in the Rustbelt, such as Detroit. However, when COVID-19 became a pandemic, this ‘flight from the city’ also affected service-labour markets. Together, these developments have induced distinctive forms, learning from both greening and digital media innovations to deal with longstanding difficulties for urban (and rural or seaside) landscapes concerning global ‘over-tourism’ in heavily over-branded, “cultural-creative” global tourism destinations, such as Venice, Florence, and Barcelona. In 2021, even the Camden Highline in London, was to be designed by Dutch horticulturist Piet Oudolf, a planting planner at New York’s Highline exemplar, while the English post-industrial town of Stockton announced that it was to demolish its empty, antiquated shopping mall and replace it with a new riverside park.

Section 1 introduces the background and scope of the paper. In

Section 2 our conceptual model is presented and explained. The ‘Surveillance’ and ‘Attention’ drivers of the ‘celebrification’ and ‘influencer’ interactive processes are delineated. Next, in

Section 3, we explore our first case investigation, which involves urban planning such as ‘soft branding’. In

Section 4 we explore the key implications of COVID-19’s effects on sustainable ‘soft branding’ in comparison with transitional experiences of changed branding effects and aspirations in our other two case investigations, to compare and contrast. Next, in

Section 5, we explore policy efforts to change urban conditions in ‘soft branding’ locations towards sustainable outcomes, following contrasting ‘open innovation’ practices concerning the moderation of ‘fast fashion’ and ‘overtourism’ excesses.

Section 6 contains our research findings, with summary conclusions comprising the ending of this chapter.

2. Open Innovation as a Persuasive Supply Chain (PSC)

The digital influencer as the ‘product of a narcissist age’ is a quote from Reference [

10] critiquing ‘digital technopoly’ as practised by Big Data social media corporations. The ‘technopoly’ belief is that the product of human labour and thought is efficiency and that technological calculus is superior to human judgement. Accordingly, Lanier’s perspective is an apt reference for the influence exerted by the head engineer at Google in Mountain View, Google’s headquarters, Ray Kurzweil. He has long been an apologist for AI, who some commentators have labelled ‘genius’ but also a proselytizer for only the benign predicted effects of artificial intelligence (AI). Kurzweil is thus an AI ‘champion’, despite his cultist association with Silicon Valley’s ‘Singularity University,’ which he established in 2008. The concept of ‘singularity’ was borrowed from science fiction writer Vernor Vinge. From a dystopian perspective, Vinge identified it as the point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible. The proximate event concerns the future, when human and artificial intelligence will have converged, as measured by the ‘Turing Test’. Named for computer innovator Alan Turing, this is taken as the point at which human and artificial intelligence cannot be differentiated by answers posed to identical questions put to both. From the life sciences, another critic, biologist PZ Myers, argues that Kurzweil mixes some innovative ideas others that are ‘crazy’. Thus, his argument about ‘AI retro-fitting the human brain’ shows he does not understand how the brain works’ [

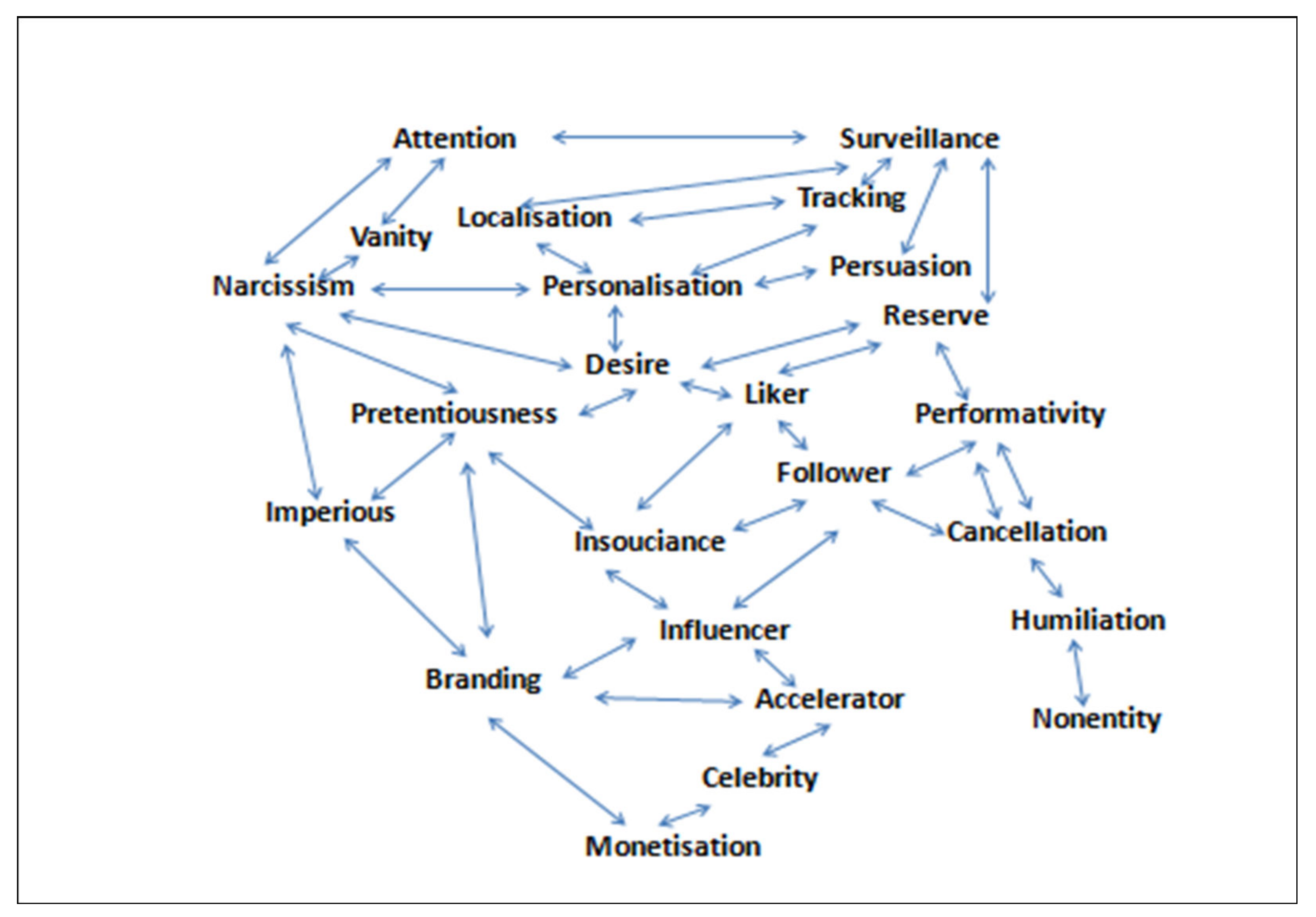

11]. Attention-seeking entrepreneurship is the apotheosis of narcissistic behaviour, which is denoted on the psychological spectrum by the deeper structure of ‘dark entrepreneurship’. In cognitive psychology, this is an example of the ‘dark triad’ of personality traits that combines narcissism, Machiavellianism and sub-clinical psychopathy. These are expressed in the Narcissistic personality as ego-inflation, self-exultation, vanity, and ‘hubris’; Machiavellianism displays cynical, paranoiac, misanthropic, exploitative and immoral beliefs; while Psychopathy is revealed in ‘imperiousness’ both towards other people and social rules or conventions, and an absence of remorse after harming others. The graphic below captures many of these traits, and the succeeding text elaborates on them. We draw on cited sources such as References [

2,

5,

12,

13] to provide an exegesis of the diagram.

In

Figure 1, we may observe the diagrammatic connections between two over-arching descriptions of digital society: one is ‘Surveillance Society’ [

14]’ while the other is the ‘Attention Economy’ [

2]. The first appropriates the identity data (ID) of cellphone owners, while the second transforms IDs into digital advertisements. Attention connects directly to itself (as attention) and indirectly to surveillance (with feedbacks). The Stanford cultural historian Girard [

10] traced human conflict to Narcissism in the following way. He emphasised ‘imitation’ as a key human trait. This is seen by Girard as a key mechanism of ‘learning’, something that is also applied by his psychologist colleague BJ Fogg [

15]. Imitation by learning means humans may desire to copy their mentor’s ideas, style and properties. Therefore, narcissism can be linked to desire, which can connect to imperiousness, or, more passively, to performativity. This leads to a bifurcation towards successful ‘influencer’ behaviour, which can have benign or positive outcomes for the would-be ‘celebrity’, or negative, humiliating results for the non-influential. The former may break the law or abide by it: the latter may become ‘mimetic’ and socially deviant. Thus ‘celebrities’ may become rivals, which may lead to conflict (known in the influencer business as ‘snarking’). Benign rivalry is referred to as ‘imitation’, but malign rivalry is conceived as ‘mimesis’. The latter can lead to harmful practice towards the mentor or self-harm towards the self. Either way, these are presented as capable of being understood as features of the ‘dark triad’, especially the dark entrepreneur or ‘influencer’ now commonly active on digital media [

16]. As George Packer described PayPal, Palantir etc. venture capitalist and libertarian Peter Thiel:

‘At Stanford, he was heavily influenced by the French philosopher René Girard [

10], whose theory of mimetic desire—of people learning to want the same thing—attempts to explain the origins of social conflict and violence. Thiel once said, “Thinking about how disturbingly herdlike people become in so many different contexts—mimetic theory forces you to think about that, which is knowledge that’s generally suppressed and hidden. As an investor-entrepreneur, I’ve always tried to be contrarian, to go against the crowd, to identify opportunities in places where people are not looking.’

Girard also discussed the notion of vengeance as an act of mimetic rivalry, ‘snobbery’ as a form of imitation, and the persuasive nature of advertising whereby if you consume, say, Coca-Cola, you may become more like the people you imitate. [

15] Fogg (below) sees the current addiction to digital handsets as likely to be seen as deplorable in future, in the manner that private or even public smoking is increasingly disparaged.

Regarding advertising, which has recently received an enormous rocket-boost from social media, that has all but disrupted traditional hard copy promotion, Wu [

2] describes Kim Kardashian’s ‘pretentious’ failure to ‘break the Internet’ with her 55 million Instagram ‘followers’. At least one of these, the relative unknown Jen Selter, then imitated her body sculpture, which, in turn, yielded 8.5 million Instagram followers. That led to sponsorship, endorsements and appearances as a newly successful ‘attention merchant’. Channeling Girard, [

2] Wu observes propagating selfiestick-centred imagery that also enables earning a living ‘as surely the definitive dystopic vision of late modernity’ [

2] (Wu, 315). He quotes other accounts of humiliation, misery, fear and self-harm among moderate celebrity aspirants at failure to measure up in the Instagram ‘vanity’ stakes. He concludes that the effects of such attention overload are historically unprecedented. In 2012, Facebook (now ‘Meta’) acquired Instagram for 1 billion USD, reneging on promises of independence from its owner, whose ‘imperiousness’ and paranoia were commented upon with the departure of Instagram’s founders.

Figure 1 recognises this ‘learning’ experience, where follower performativity failure leads to remorse and relegation to the non-celebrity also-rans. Our methodology is to take key elements of our conceptual model to investigate the extent to which, for example, ‘influencer’ plays an ‘open innovation’ role in effecting change. Here, the ‘branding’ of urban imagery and the extent of ‘sustainability’ are subject to pervasive system ‘shocks’ such as pandemics in the face of negative or otherwise unsustainable inherited consumption practices. As we conclude below, there are some discernible effects of the conjectured kind.

To conclude this exegesis, we draw on Faroohar [

14] to complete the present narrative background on the subject of ‘persuasion’ and its pedagogy. The owners of Instagram before it was acquired by Facebook had also been students at Stanford University, whose Persuasive Technology Lab was directed by B.J. Fogg [

15], a psychology professor. His lab crafted ‘captology’, the digital ranking device used in ‘gamification’ in games such as FIFA Mobile. This is a key ‘surveillance’ technology, prized by advertisers and their clients for ‘rendering’ [

14] customers by capturing their ‘attention’ and turning it into an ‘addiction’. Fogg is a disciple of B.F. Skinner, the radical behaviourist psychologist responsible for a notion of ‘learning’ (cf. Girard) based on stimulus response reinforcement and ‘rote learning’, where the learner has no opportunity for reflection or evaluation but is simply dominated by the teacher’s control and instruction of what is right or wrong [

17]. Fogg [

15] sought to expand that purview, first to improve human habits, for example, by discouraging smoking, but later connecting through Google with advertising driven by less benign motives using captology to data-mine electoral behaviour. The key ingredient for ‘hijacking’ user ‘attention’ towards apps was shown to be ‘vanity’ with ‘intermittent variable rewards’, as was successfully demonstrated in experiments on laboratory rats. According to Faroohar [

14], such digital flattery was inverted by Facebook bragging to advertisers that it could ‘track’ when teenage gamers or users’ moods included feeling ‘insecure’, ‘worthless’, ‘stressed’ and a ‘failure’, or what the author disapprovingly calls ‘wanton commodification of our attention’. Zuboff [

16] refers to this as surveillance capitalism’s ‘original sin’.

3. Urban Planning as Soft Branding

As the post-industrial era replaced mass-industrialisation and its increasingly abandoned legacy buildings, city planners began to revalue the branding of legacy townscapes as cheap accommodation for artists and other creative workers. Observing the phenomenon of 1960s–1970s ‘hippies’ becoming occupants of ‘honeypot’ abandoned settlements, which attracted tourists to acquire their often-quirky cultural products, they began to promote soft-branded tourism and cultural offers tracking old goldfield, silver mine or railroad trails as an alternative to hard-branded ‘sun and beach’ mainstream tourism. One of the earliest examples of this form of ‘urban narcissism’ occurred in New England. What was once an abandoned textile belt of abandoned Massachusetts mills was re-branded as Mass MOCA, located in North Adams. The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art lies in a traditional area of textile mills powered by the Hoosic River and is part of a wider area of small mill towns that spread across the border into upper New York State. The Sprague electric capacitor concern that occupied the Arnold printworks employed more than 4000, mainly female workers in a settlement with many of the features of a company town, which nevertheless closed in 1985.

Williams College acquired the buildings almost immediately as an art exhibition space, a process that was itself exhibited in photographic displays entitled Mass MOCA: from Mill to Museum. Funding for conversion was public–private in origin, with the state, arts institutions and foundations operating in partnership, and it opened in 1999. The mission was to revive the artisanal traditions of the region by restoring its native textile arts and printing in a new form. To that end, semi-permanent exhibitions by celebrated artists like Sol LeWitt and Anselm Kiefer were hosted, respectively, by the Yale University and Williams College Museum of Art until 2008–2033, and by the Hall Art Foundation until 2028. Other celebrated artists exhibited in these collective displays have included Jörg Immendorf, Robert Rauschenberg, Jenny Holzer and Ed Ruscha. Since 2001, annual music festivals have also been held at the MOCA buildings and in the open air. These, along with dance, theatre, film and concerts, are accommodated and partially funded by MOCA’s average of 300,000 visitors and the commercial rents of 37 business tenants that create 50 m USD in turnover each year, many specialising in online and offline branding. Special attention was paid to housing large-scale art exhibitions promoting installation, land-art and minimalist genres, making use of the larger-than-normal space provided by the site. Another continual emphasis is on training, advisory and consultancy in diverse modes of ‘branding’ design. This is expressed in the museum’s own soft but distinctive branding, which combines the regional tradition of textile printing with contemporary artworks.

Despite Mass MOCA’s tribute to its own urban-industrial past to maintain a degree of authenticity in the presentation of its self-image, it has to be admitted that this is a matter of degree only. What is really going on, as occurs in cultural–creative planning nearly everywhere, is an exercise in persuasion to attract the attention of residents, migrants, visitors and investors and monetise their taste for the quirky or unusual in the ambience of the restored, repurposed and revived industrial setting, which is shaped into a ‘soft branded’, post-industrial, perhaps post-modern, ‘simulacrum’ [

15]. To underline this judgement, we briefly turn to the manner in which cultural planning policy was pursued in the neighbouring state to North Adams, namely upstate New York, and the comparable industrial villages and towns of the Catskill Mountains, such as Schenectady, Troy, Saratoga Springs and Glens Falls [

18]. Of interest in this analysis [

19] is the elision Should only be [

18] between the quest for ‘authenticity’ in planning and in Internet studies. The latter includes studies of ‘influencer culture’ and the ‘attention economy’, but both authenticity and social media combine to create desires at the individual and jurisdictional levels for the consumption of online and offline identity performance. The promotion of ‘identity’ in hollowed-out but post-industrial ‘New Urbanism’ [

20] had begun to attract younger migrants from the over-developed, high-rent and highly polluted atmosphere of metropolitan locations even before the onset of COVID-19 [

21].

A post-industrial brand based on ‘authenticity’, walkability and low rents that enable working from home has persuaded new residents to move and cultural planners to persuade town authorities to compete for cultural capital grants, of which Glens Falls was a recent recipient. Brand advertising as a means of persuasion is mainly conducted on social media, notably Facebook and Google. Here, influencers monetise their appeal to new residents and address social media concerns by reference to their entrepreneurial offers in terms of design, fashion, fitness, entertainment and, as available in North Adams, ‘branding’ itself. The Glens Falls’ winning bid on the state Downtown Revitalization Initiative emphasised a Farmer’s Market with associated retail, artisan spaces and restaurants, including kitchen demonstrations that promote ingredients from local agriculture. Complementing the food offer was a culinary institute, enhanced parkland, public art exhibitions and seed funding for revived downtown artisan shops, as well as enhanced Internet access with improved broadband. Elsewhere, this is seen as an exemplar of what was once labelled the ‘New Urbanism’ or the fashioning of inauthentic authenticity [

20]. In 1985, Don De Lillo’s novel ‘White Noise’ [

22] drew attention to the tourist phenomenon of ‘the most photographed barn in the world’, which was famous for having been photographed so often, rather than for any visibly intrinsic or even historic value. This is the apotheosis of the postmodern ‘simulacrum’ [

15] realised by the ‘woke’ conjuring trick of combining ‘smoke and mirrors’. Unfortunately, COVID-19′s effects have likely interrupted hopes of urban revitalization based on food and the arts, while only some ‘influencers’ have thrived on images of ‘commodity fetishism’ and the ‘cult value’ [

22,

23] of celebrity, commoditisation and consumption via social media.

4. Has COVID-19 Changed the Aura of Place?

During 2019–2021, there was a major undermining of the ‘aura’ of events and places staged or located in real spaces in favour of their ‘post-auratic’ representation on various media. How do brands, influencers and celebrities emerge from their various experiences of lockdown, regarding their interactions? Focusing on influencers first, they have fared either badly or well, depending on their field of ‘expertise’. Thus, travel influencers have fared badly [

24]. Brands hesitate to embark on new influencer partnerships due to the financial impact of the pandemic. Further, the impact on travel influencer business has been severe, as most influencers profit from displays in glamorous, not to say ‘auratic’ destinations, and are sponsored for trips promoting hotels, destinations, airlines and tourism-related brands. Finally, the influencers capable of travelling to Instagrammable settings were heavily criticised for continuing to produce travel imagery—insouciantly sharing ‘tone deaf’ posts using inappropriate hashtags. The result is that influencers have had to work from home and intercut video with pre-pandemic footage, immediately losing the travel accessories of ‘authenticity’, ‘aura’ and ‘immediacy’—even including efforts at comedic value for entertainment and ‘profile’, for only a minimal reward [

25].

Some travel influencers have raided archives for ‘best of testimonial’ films, much like mainstream media sports channels, where legendary performances in matches often recorded decades ago are shown. Additionally, one result of missing an entire season of content creation has been concerns regarding when brand partnerships might be resumed and whether travel sponsors will continue with ‘influencer’ marketing. Filling in ‘deadtime’ involved ‘sharing’ existing content as retrospective ‘throwbacks’, causing influencers to edit previously unexamined photos to create new copy. Despair at having such stale work means that incumbents sought to diversify because travel influencers are perceived to have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. This could mean attempting alternative courses, including food blogging, as a way to create home-based, content-seeking brands that may experience an uplift in sales. The imperative to acquire a balance between creating inspiring captions, while not looking like they are having a whale of a time as ‘followers’ suffer, is crucial. The ‘travel influencer’ report’s author [

26] urges travel influencers, paradoxically, to adopt longer-term digital content strategies that allow them to remain ‘relevant’ but ‘prosperous’ within the sector. This would involve an avoidance of the currently ‘post-auratic’ international travel by choosing to re-purpose old content, or branch into adjacent disciplines. Effectively, the global travel landscape is currently perceived as fundamentally uninhabitable for such digital chroniclers.

Thus, ‘influencers’ can be ‘local heroes’ with only 5000 followers, influencing their small town, and range up to mega influencers, with tens of millions of followers. During the pandemic, some new sectors emerged as fashion and make-up blogs lost their appeal; new or diverted offers include medical advisers, grocers, delivery drivers, and other front-line staff. One of the effects of the pandemic and, in the UK, Brexit, has been the increased fragility of supply networks due to shortages of drivers to deliver energy, food and retail products. These are groups that audiences are interested in following and hearing from during the crisis. Among the key findings of 2020′s State of Influencer Marketing Report were a decline in sponsored content from ‘brands’ that hitherto paid ‘influencers’ to Instagram their commercial product in ‘advertorials’. This led influencers to more extreme, luxury, or otherwise niche ‘brands’ of greater value [

27]. US data revealed that both the amount of content paid for by sponsors and the number of sponsors partnering with influencers declined compared to 2019. Transactions between sponsors and influencers dropped by 37% compared to 2019. The advertising decline in 2020 was related to the global pandemic. Therefore, in line with our leading conjecture regarding a rise in ‘green’ influencer activity during the pandemic, to what extent has ‘green’ or ‘sustainable influencer’ performance been similarly affected? As a result of COVID-19, there has been growing interest from audiences in influencers promoting ‘green’ interests [

28]. Widespread fears regarding food availability provoked public interest in food systems, while dependence on food banks highlighted the many people struggling to provide meals. Farmers announced that almost a third of the harvest could be wasted because of the reliance on around 60,000 migrant fruit and vegetable pickers. The closure of restaurants and limited take-away services were expressed by an upsurge in home-cooking and baking, a shift to local retailers and the growth of veg-box schemes. Overall, food sustainability had a greater influencer uptick than many other sectors. Accordingly, aura of ‘place’ is tarnished for ‘influencers’, as further distance-to-destination is required, but ‘locality’ has been restored in status, albeit due to convenience and ‘authenticity’ is likely preferred to ‘aura’ [

29].

To repeat, the key aims of this paper are, first, to understand the growing involvement of digital methods in consumption practices in contemporary and future society and second, to understand the impact of digital devices on citizen engagement in controlling climate change by using ‘green’ everyday practices, facilities and ways of living. To illustrate the extent of these, we use the following ‘vignettes’ as illustrations of practices or the possibilities of relevance. First, we briefly exemplify the digital–green interaction involving ‘influencer’ intermediation in the formation and transformation of what was traditionally seen as a Renaissance Art City into a ‘Fashion City’ during the post-World War 2 consumer era. However, the rise of ‘fashion’, especially ‘pronto moda’ or ‘quick’ fashion, developed a bad image regarding fashion production in general because of its excessive use of polluting and over-excessive raw materials such as cotton, dyes and water in production and excessive waste in consumption. We then indicate the efforts that are being made and planned to further transform ‘fashion’ as a label due to its unsustainable ‘brand’ image. In our second vignette, we present accounts of the manner in which digital–green interaction has been used by the engagement of a global, soft-branding ‘influencer’—Madonna—in Lisbon’s element of Portugal’s green transformation policy. The third and final vignette underlines the aspects of our ‘green analysis’ and envisions the steps taken by ‘digital–green’ interactions in managing the important climate change ingredient of ‘global tourism’, which contributes massively to global heating. Temporarily halted by COVID-19, ‘overtourism’ seems set to continue unless there is a radical transformation in global mobility, accommodation, subsistence and entertainment costs.

Remaining with the ‘brand’ invention of ‘Made in Italy’ fashion, as expressed in Florence’s ‘Fashion City’ re-branding, the following is instructive of the deeper structures facilitated by the ‘pattern recognition’ methodology [

28,

30,

31]. If we counter ‘dark triad’ psychological characteristics with the so-called ‘light triad’, we first observe that the ’traits’ emphasise: a belief that humans are basically good; belief that all humans across all personalities deserve respect (Humanism); the Kantian belief that others should not be instrumentalised and that the ‘crooked timber’ of diverse personalities deserves respect. Research into ‘light triad’ personality traits revealed them to be typically more spiritual and religious, with higher life satisfaction, acceptance of others, compassion and conscientiousness, than ‘dark triad’ respondents [

32].

Sennett [

33] showed how Kantianism also refers to ‘crooked timber’, which is the Kantian idea of cosmopolitan life whereby humanity can never be truly straight because it is so variable, mixed and unequal. Accordingly, the ideal ‘image’ has to be contextuated by the circumscribed ‘reality’ that is observed and accommodated. The traits researched by Light Triad observations concluded that respondents tended to be older, female and to have experienced less unpredictability in their childhoods. Respondents also tended to report higher levels of religiosity, spirituality, life satisfaction, acceptance of others, the belief that they and others were good, compassion, empathy, openness to experience and conscientiousness. Elaborating on the categories mentioned after our paper’s Introduction, as listed in the following, those scoring high on the Dark Triad characteristics of Narcissism, Machiavellianism and Psychopathy tended to be younger males and were psychologically more driven by success, power, fleeting sex and relationships [

32]. Unpacking Dark Triad personality traits, Narcissism includes an inflated ego, control-freakery, exultation, vanity and ‘hubris,’ being admired and acknowledged by others; Machiavellianism is characterized by cynical, paranoiac, misanthropic and immoral beliefs; emotional detachment; insouciant and self-serving motives; strategic long-term planning; manipulation and exploitation; while sub-clinical Psychopathy is denoted by ‘imperiousness’ towards both other people and social regulatory mechanisms, impulsivity, ingratitude, and a lack of guilt, mortification or remorse for harming others. The point here is that the interplay between the dark and light aspects of personality and community is the object of inquiry in a Socratic mode of disclosing contradictions in human action.

Accordingly, in summarising Lazzeretti and Oliva’s [

34] account of the triumph of the Fashion City ‘brand’, triad analysis means that we must balance this against ‘pronto moda’ and its socio-environmental negativity. Historically speaking, the first high-fashion show held in Florence was in 1951. It was welcomed as the beginning of an international evolution of Italian design by the initiation of the ‘Made in Italy’ brand. The promotional activities of Giovanni Battista Giorgini [

9], chief buyer and organiser of the first Florence fashion shows, reveals its rise in reputation in the national and international fashion journalism of the ’Made in Italy’ brand in the 1951–1967 period. Florence appears as the first centre for Italian fashion design and commerce, preceding other cities, notably Milan, in this achievement. Explanations for this first-mover status include stressing the geography, the cultural inheritance ‘Renaissance effect’, and the industrial structure and globalisation of ‘Fashion City’ candidates. Milan, for example, is, unsurprisingly, selected in studies, but not as early as Florence [

35] (d’Ovidio, 2015). These authors’ research method of using online databases expresses the idea that the digital revolution has cognitive effects, simplifying access to a huge amount of information through digital means, such as online databases. ‘Made in Italy’ displayed respect for ‘the Italian way of living’ and captured the 4Fs: fashion, food and wine, furniture and ceramics, and fabricated machinery [

30]. Therefore, collective ‘Light Triad’ traits, emphasising ‘goodness’, quality and design, formed the ‘branding imagery’. Reinforcing these were the ‘humanity’ of cultural heritage, emphasizing the beauty and high quality of Italian craftsmanship, albeit designed for a global ‘mass customisation’ market. Countering that, in an imperfect world, economic competition meant that a competitive advantage had to be exploited through the relocation of production, but not design, to cheaper, foreign labour zones. Moreover, ‘brands’ could be copied and become ‘stereotypes’, and small workshops were acquired by foreign luxury corporations. This was most clearly expressed in Giorgini’s expansion abroad, particularly to the USA, first enticing buyers to exhibitions that he organised in his Tuscan villa and, the following year, in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. The Ferragamo and Gucci companies are also Florentine in origin; Ferragamo opened its first US shoe store in New York in 1938, followed by Gucci couture in 1953.

In a paper on the dark side of digital culture and the humanistically centred tradition of ‘creativity’, Lazzeretti [

36] points to aberrations such as ‘attention’ absorption, its relationships with ‘addiction’ and the undermining of ‘privacy’ through the deflections of ‘surveillance’. Meanwhile, digital systems driven by artificial intelligence (AI) are slowly appropriating creativity, but as yet only ‘ape-like’ creativity, using machine learning. At present, an even more complete appropriation using digital artists’ imagery is found in the innovation of the ‘digital provenance certificate’ (or Non-Fungible Token (NFT)), by which they may be well-recompensed (although only by the Etherium bitcoin) for their recombination skills. We thus reach a more generalised ‘dark side’ introduced by the competitive industry pressure that first invoked digital textile design. The response to foreign competition led to ‘pronto moda’ in Italy, as the label suggests. The Italian ‘economic miracle’ in the 1960s rested, to a great extent, on the revival of the post-war textile industry and, once again, the US market was crucial to its development. Intermediary agents from Italian clothing districts intent on finding cheap cotton goods markets were informed of a rising demand for white cotton T-shirts inspired by certain ‘rebel’ film stars of the day. Production on affordable Italian weaving machines, at a better price, including transportation, was cheaper than in the US. Products sold well and colours were later introduced, including steamed wild-animal designs. These sold even better until Indian producers learnt how to make cheaper ‘Tiger’ designs to export into the same US market by the end of the 1970s–1980s. Italian producers were forced to find a way to design patterns on both cotton and woolen knitwear. This was accomplished at specific regional technology centres near Bologna rather than in Florence, which opened faster, cheaper and more design-intensive markets in the US, Europe and, later, globally. By 1990, this innovation was branded in the discourse of ‘pronto moda’, ‘quick fashion’ or ‘fast fashion’. Branded goods were often sold at a discounted price in US, Japanese, Chinese and German department stores and, by the 2000s, in UK chains such as Irish firm Primark or the home-grown New Look.

Pronto Moda is cheap, frequent and disposable, which makes it unsustainable at both the production and consumption ends of the manufacturing chain. It relied first, upon the automation of design and layout using computer-aided design and production, which are robotised and cheap, although production in Bangladesh is cheaper than Italian production due to the lax safety regulations, and second ‘point of sale’ re-stocking of popular lines, ordered by just-in-time delivery at the store end of the process, which further cheapens output. The first point-of-sale re-stocker was the Benetton brand; this was later improved by Zara and is now the industry standard. It is immensely popular, as up to six or more fashion changes can be quickly introduced. Affordability is enhanced through automated design and manufacturing, or by unregulated factory safety. Such purchases are disposable after being worn for a weekend, or once. The dyes and chemicals used in garments are polluting, water-wasting, and poisonous to river wildlife. There has been growing condemnation and criticism of these methods on social media. Unfortunately, more posts extolling ‘fast fashion’ are promulgated by widely available, ‘influencer’-driven digital marketing. Fast fashion has evident features of Dark Triad consumption and production traits: through Narcissism, which plays to consumer ‘vanity’, ego, and ‘hubris,’ experienced through the other’s ‘attention’ as advertised to consumers; Machiavellianism at the production end, through factory fatalities, management cynicism, manipulation, paranoiac, misanthropic and immoral beliefs; and Psychopathy due to unconcerned ‘imperiousness’ and a lack of remorse after harming others. Accordingly, ‘pronto moda’ is a classic case of ‘bad branding’. The fashion and clothing industry is responsible for about 10 percent of total global carbon emissions, and is estimated to increase by 50 percent by 2030 [

34]. To some extent, ‘pronto moda’ has occluded the aura of ‘Made in Italy’ for three main reasons. First, in the direct cotton clothing and textile manufacturing business, prodigious amounts of water are utilised to excess. First, the manufacturing and production of a single pair of denim jeans consumes 6600 L of water, and 3000 L is needed to make one T-shirt. A total of 13.2 sq. metres of land is needed for jeans, along with 0.5 kg of fertilizer and 103 different pesticides, with about half that for a T-shirt. Second, world production has reached ‘peak cotton’, consuming 11% of all agricultural chemicals and 25% of all pesticides each year. Finally, clothing wastage results in 350,000 tonnes of clothing being discarded each year in the UK alone. Observing the current metrics, the clothing industry will account for 25% of global carbon emissions by 2050. ‘Fast Fashion’ is clearly a product ‘brand’ of ‘Dark Triad’ cultural traits that, by increasingly digital means, victimises its consumers through social media ‘attention’ advertising and influences shopping behaviour that borders on the addictive and irresponsible. However, criticism is muted and rarely seriously acted on by conventional politics. The Hoffmann Centre [

25] reported that, while manufacturers pay lip-service towards tackling the sustainability of ‘Fast Fashion,’ relatively little effect has been observable regarding the unsustainability of the industry [

25]. By contrast, recent data on the ‘green influencer’ effects on fast fashion unsustainability show that, for the survey respondents (in total >2000), those in the 18–24 age range recorded 43% as having their changed buying habits from fast fashion to second-hand or vintage clothing instead. This was double the rate of change for respondents over 55. Approximately 41% of 18–24s who had reduced their fast-fashion consumption changed their habits due to environmental, waste and sustainability concerns [

25]. Continuing with the younger cohort respondents:

- ▪

Nearly two thirds (65%) said they were influenced by the treatment of workers in the supply chain;

- ▪

57% of people said the sustainability of how the clothes were produced was a factor in the fashion choices they made;

- ▪

55% of people said they are more likely to buy clothing that they know has been produced in a more sustainable way;

- ▪

More than half (51%) said they would be willing to pay more for clothing if they knew it had been produced in a sustainable way [

25]

.

5. Innovating ‘Open Innovation’ by Greener Influencing and Envisioning

Open innovation using a different kind of ‘influencer’ activity is expressed in the following examples. These consist of brief accounts, mainly from Portugal, which are more directly related to ‘celebrity’ than to ‘couture’. The open innovation novelty is ‘celebrity endorsement’, which is mobilised in the pursuit of sustainable development in a city-region. The proximate event was Madonna’s move to settle as a resident of Lisbon. She followed the celebrity practice of Ian Fleming, Christian Louboutin and Monica Bellucci of being inspired by the city’s culture. For Madonna, that involved writing, singing songs and producing three Portuguese-inspired videos for her current album. Simultaneously, the scholarly popular psychology literature showed narcissism to be a fashionable research topic, seen by the authors of References [

3,

4,

37] as important in fans’ selection of tourism destinations. Experiencing celebrity-related destinations is seen as seductively consuming the desire that the celebrity image may express [

9]. Thus, celebrity endorsement has become a marketing mechanism for brand promotion. Following Urry [

38], co-presences with ‘celebrity’ are spatio-temporal relations that provide ‘singularity’ to specific places. This has been researched for K-pop in South Korea [

39], showing an exponential rise in foreign tourists [

40], and now in Lisbon in relation to the ‘Pop Queen’s’ residence there [

41,

42]. The promotion of K-pop by the South Korean is also shown to be associated with a rise from 300,000 overseas tourists in 1998 to 11.8 million by 2014 [

40,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Inspired by the ‘slow tourism’ vision, Nunes and Cooke [

42] evolved a ‘post-auratic’ digitalised model of cultural ‘simulacra’ [

20,

47] to moderate ‘overtourism’ in iconic locations. To exemplify, in Philip K. Dick’s novel

The Simulacra [

47], the reunification of Germany is envisioned thirty-five years before it actually occurred. The novel further dealt with the ‘Dark Triad’ trait of Psychopathy, tackled later in Ridley Scott’s film ‘Blade Runner’, adapted from Dick’s 1968 novel

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? [

48] The novel shows how the problem of reintegration of Germany is resolved by Android Psychopathy,’… in which the failure to empathize and mourn tests the limits of tolerance’ [

49]. Addressing the issue of ‘overtourism’ [

27,

50], the development of massive ‘Gigasheds’ is envisioned, to accommodate multiple sites for ‘immersive’ cultural activities, large-scale replicas of wave pools, artificial beaches, hologramic VR and AR ‘gamification’ concerts, galas and dramas, with varieties of replicated museums, galleries and historic attractions as simulacra that solve the Psychopathy of ‘auratic global overtourism’. The announcement of ABBA’s return to the immersive arena stage as a hologram of their 1970s ‘simulacrum’ shows that academia is ahead of the renewed ‘influencer’ game [

51,

52,

53]. In a curious case of the ‘multiple’ innovative idea (that occurs simultaneously yet independently), Bruno Frey [

54] had a similar idea for tackling ‘global overtourism’ by building replicas of ‘… a St. Mark’s Square in Venice called ‘Mark 2′, creating a look-alike Louvre, and carrying out the same for more than 100 sites suffering from overtourism’. Frey, quoted in

Der Spiegel in February 2021, was clear that:

‘Rather than the terrible copies of tourist attractions in Las Vegas and Disney World, the sites proposed would be ‘new originals’ filled with new technologies and holograms, which would make the copies the first choice of many people wanting to visit.’

This further underlines his idea of ‘Revived Originals’:

‘The aim of Revived Originals thus is not just passively to reconstruct the major buildings but explicitly to offer a vivid cultural and historical experience to tourists. Many tourists prefer such a lively introduction, reflected by the growing trend of ‘edutainment.’

Such simulators could also be innovatively applied to the related problems of appropriation, such as the return of heritage exhibits removed during the era of colonialism and empire-accumulation. Thus, Greece’s claims on the Elgin Marbles are a case in point, where reviving the original through digital replication may be superior—apart from its ‘aura’—to the damaged original.

Thus, nearing the end of these vignette accounts, we have begun to trace how ‘influencers’ who, like academics, are very familiar with the norms of ‘celebrification’ by virtue of their requirement to publicise, persuade and ‘narcissistically’ sell their publications in the neoliberal world of research ranking, evaluation and market-assessment, Similarly, attractions create ‘attention’ for selfie-wielding crowds in ‘overtouristed’ global attraction spaces. Of great interest is how path-dependence on the construction of one successful ‘brand-image’ mutates into another one. For example, how does ‘Fashion City’ move to ‘Sustainable City’ when fashion has lost some of its lustre as a sustainable ‘brand’? Here, we may observe the emergence of an evolutionary selection process, as follows. Many cities worldwide have been able to relaunch their image thanks to green conversion and city branding towards smart-green cities, widely supported by new technological innovations (e.g., Artificial Intelligence, digital platforms). Several cities are implementing sustainable development plans for a smart transition (e.g., Paris, Barcelona, Milan, Vancouver, New York). Designation as a smart city not only means adopting technological innovation in management in the urban context but also discovering environmental innovations for the more efficient allocation and use of scarce and irreproducible natural resources. This further implies the improvement in citizens’ health and co-participation, and the growth of an urban green image. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe has recently defined the smart sustainable city as ‘an innovative city that uses ICTs and other means to improve quality of life, efficiency of urban operation and services, and competitiveness, while ensuring that it meets the needs of present and future generations with respect to economic, social, environmental as well as cultural aspects.’

Our final case is that of the city of Florence, which, as we have seen, has made efforts to implement new technologies to make the city more livable and greener. Florence is also well-known for its historical, artistic and cultural heritage, which attracts visitors worldwide. The cultural and tourism sectors co-exist with the industrial structure of the city, characterized by the presence of the fashion industry. Fashion retail and ‘experiences’ centred on manufacturing and production activities overlap with cultural and touristic ones [

56].

Policymakers have presented a new city plan, combining the concept of the Smart City with that of Green City for the efficient use of economic and environmental resources and to relaunch the city’s brand image after the post COVID-19 pandemic. In October 2020, Florence signed the Green City Accord, a European initiative to achieve green strategy goals, speeding up the implementation of EU environmental laws and the European Green Deal. As a part of the project, the Firenze Smart Green City digital platform was funded through the Agenda digitale dell’Osservatorio School of Management del Politecnico di Milano’s award. The digital platform has four main objectives: first, to build an urban public parks map through a new information system developed by the GeoSystems company, a mobile app that allows for the protection and surveillance of Florence’s public parks in real-time; second, Dona un albero (give a tree), to donate a tree to each person and to each newborn child; third, the Smart Irrigation project, funded by the EU Horizon2020 Smart City Lighthouse ‘Replicate’, which saves 30% of the water in the city’s public green areas; finally, the Smart City central chamber, also funded by the Horizon2020 Smart City Lighthouse ‘Replicate’, which represents the central point of the strategy. The project envisages a ‘control room’, grouping all the control centres for mobility, traffic management and maintenance, video surveillance systems, urban bus and tramway traffic, as well as the control center for the waste collection, street sweeping, municipal police and firefighter services.

The city projects represent an opportunity to overcome the issues related to Florence’s ‘overtourism’, which have affected the historical centre, increasing the presence of hotels and AirBnbs that have exacerbated the gentrification phenomena in the real estate market, leading to depopulation of the city centre for Florentine citizens, and the closing of several activities in the historical botteghe (workshops). Analysing the case of Florence as a smart green city could provide insight concerning the re-branding of a city using digital technologies for its environmental management, and contribute to the study of how historical art cities may develop efficient policies to counter the loss of authenticity, overtourism issues and the risks of an excess of ‘liquid modernity’ [

57,

58,

59].