Abstract

With globalisation, there has been an intensification of investments by foreign groups in sectors strategic to their country of origin, such as some minerals. It is, therefore, crucial for a parent company to implement specific controls in its management control systems. In these circumstances, this study aims to determine the degree of control exercised by the parent company over a subsidiary in cultural and organisational dimensions. In addition, other exogenous factors (entities and external factors) influence this system. The results obtained showed that the parent company had an influence on the Management Control System (MCS) of the subsidiary and changed the way control was exercised there, but was unable to deal with macroeconomic instability, environmental and strategic uncertainty, and, consequently, the management risk involved in the extractive activity; in this case, for this subsidiary to operate a seam mine and not be aware of it since it is essentially a commercial, economic group. In addition to these effects on the organisational dimension and the cultural dimension, the shareholders were unable to integrate the subsidiary’s organisational and local culture, which generated some dynamic tension with the expatriate. In addition to the theoretical framework used, it was confirmed that the Flamholtz model is passive to implement in industries in general, particularly in the extractive industry. Finally, some final considerations were made about the management control system, in which the argument is reinforced that there must be empathy between the local staff and the expatriate, as a representative of the shareholders, in order for this system to be a vehicle for the effective transfer of knowledge between both parties, as well as to be supported by open innovation.

1. Introduction

Gond, Grubnic, Herzig, and Moon [1] refer that organisations’ sustainability involves the renewal of organisational strategy and the creation of new management practices, strengthening the link between management control and strategy since their congruence (common objectives) directs organisations towards that sustainability. In this context, organisations must adopt a strategy that emphasises the use of a management control system (MCS) as a tool for the proper implementation of the strategy, in which competitiveness is seen as a vehicle of distinct, capable, and valuable resources that are controlled by the organisation [2,3].

Logically, the relations between multinationals and their subsidiaries are closely linked to the phenomenon of globalisation. Organizations have become increasingly geographically dispersed and involved in business worldwide; in this sense, multinationals are composed of organisational units located in different countries. This highly dispersed situation instigates the need for effective business integration (integration of subsidiaries) and the need to balance integration, independence, coordination, strategy, and control [4,5]. Additionally, Yeh [6] defended the importance of balancing parent companies’ social and bureaucratic controls when they manage their subsidiaries.

With these changes, managers are currently concerned about controlling their organisations and employees, so control is crucial to achieving the objectives [4]. Control reduces uncertainty, increases predictability, and ensures that behaviour from different parts of the organisation is compatible [4]. Through the use of control mechanisms, the interests and lines of action of the different parts of an organisation are aligned; this alignment can occur between top management and middle management, between managers and employees, and between the multinational and its subsidiaries [4].

In other words, MCSs have to underpin the strategy, this being a current area of research in the scientific community. Thus, to study this research topic, the new institutional sociology was adopted, which is premised on the use of structures and processes that are legitimated and standardized, as well as a part of an integrated whole, and approaches the MCS as a set of management practices and not only as a mode of control per se, and studies the organizational relationships between the parties involved. The new institutional theory was developed in the late 1970s based on various system theories open to organisations and the premise that the environment affected organisational practice [7]. This theory argues that they assimilated the practices adopted by organisations due to a cultural process and not only as a formal means to improve their efficiency, according to the same author. In short, the focus of this theory is on the macro-organisational environment and the legitimisation strategies of organisations [7].

This article aims to study the impact of the surrounding institutional environment and strategy on the MCS in a subsidiary operating in Portugal owned by a foreign economic group. In order to achieve this objective, the following research questions arise:

- (i)

- How does the parent company influence the subsidiary’s MCS (cultural and organizational dimensions)? (Q1)

- (ii)

- What other factors influence the subsidiary’s MCS (external entities, price, risk, strategy)? (Q2)

2. Literature Review

Organisations are part of an economic and social environment, which has a strong influence on them because they need to adapt to the external environment’s requirements to remain competitive. In the past, several leading organisations have seen their positions decline, as managers have not been able to see beyond, innovate, adapt their resources, and exploit their experiences. This corporate short-sightedness has led several successful companies to regress due to their “short-sightedness” in adapting to the market [8]. Organisations must take an active role in adapting to their surroundings by drawing on their resources and skills [9]. The dynamic advantage in turbulent markets is only attainable due to organisations’ ability to adapt continuously to changes in their environment, customer requests, and available technology [10]. The focus of organisational attention is on rapid adaptation to environmental requirements, and the consequent need to create and renew resources and reconfigure the range of existing resources [11,12]. Organizations that develop new products have the impact of a positive resource of the exploratory configuration [13]. Based on dynamic capabilities, organizations are allowed to reconfigure themselves according to the market. However, due to this need for constant adaptation, the competitive advantage is not fully attainable because it is continuously renewed [10,14]. It is precisely this capacity that differentiates them from ordinary capacities [15].

The studies of large Japanese organisations present an image of an organisational configuration based on a system of cultural control, with assumptions based on human-resource skills and organisational commitment, which contribute to adopting a global strategy [16]. In other words, based on the cultural differences between multinationals and their subsidiaries, there is once again the phenomenon of globalisation, which poses enormous challenges to management control practices, in which they have to adapt to the variable location and its inherent dimensions [17]. According to these authors, control cannot be understood as a mere technique that encompasses procedures and practices, people inserted in an organisation, and a relationship with national cultures. However, the culture of each location or country and the company’s organisational culture is also important; for example, Japanese companies are characterised predominantly by a market and hierarchy culture [18]. Cross-border procurement represents a strategic investment by multinationals to overcome globalisation’s competitive pressure and improve its global market position [19,20]. For Ivarsson and Vahlne [21] acquisitions are the most common form of foreign investment. In this context, cross-border acquisitions are the only way to gain a competitive advantage by improving organisational efficiency and effectiveness. These acquisitions are a common and complementary thread for involving capabilities, i.e., the complementarity of the capabilities, skills, and knowledge of multinationals versus subsidiaries; thus, multinationals undertake investment strategies to improve their positioning in their international operations, since the acquisitions, partial or total, allow them to exercise control over the subsidiaries in order to achieve their objectives and influence the management of the subsidiaries using their power, authority, culture, and a wide variety of bureaucracy as control mechanisms [19].

But acquisitions add value for the acquirer through economies of scale; possible cost reductions; access to new markets; raw materials; natural, financial, and technological resources; and intellectual capital [22,23,24].

Given the importance of the strategy in recent times, several approaches have been used to explain multinationals’ strategy, including institutional theory, based on the assumption that the strategy must be adapted to the ongoing global and local changes [25]. In the case of multinationals, these authors have argued that strategy is the way to improve the parent company’s relations with its subsidiaries, allowing the barriers that exist for the latter to have practical autonomy within them to be overcome [25].

From another perspective, these acquisitions by multinationals also represent added value for the acquirer through economies of scale; possible cost reductions; access to new markets; raw materials; natural, financial, and technological resources; and intellectual capital [22]

The strategy has been seen as fundamental because it explains why some companies are successful while others are not; for this, internal and external factors must be considered [26]. Thus, some studies address multinationals’ strategy in various contexts and their relationship with the environment [26].

Regarding strategic planning in the mineral industry, the main challenge they face is how to create sustainable value with their operations, their strategy, taking into account the inherent constraints and market conditions, which implies long-term strategic planning, using a set of tools and techniques such as common language, standards, systems and processes, so that decisions and actions are aligned on a cyclical basis [27].

Based on the rigour’s demand on the management strategy, dynamic capabilities reveal themselves as fundamental to the adaptation, integration, and reconfiguration of resources, which will consequently leverage new horizons [12,14,28,29].

Global and national business environments, together with market characteristics, create the operational context in which scenarios are developed for the application of planning, allowing the understanding of the business environment in which the company operates, and also the understanding of the drivers of change; possible scenarios are developed over the long term, based on global assumptions such as demand, metal prices, and exchange rates; the same can be defined as one that influences decision-making to use resources and capabilities, including social, political, economic, regulatory, tax, cultural, legal, and technological aspects [27].

Because companies have no control over the external environment, their success depends on how well they adapt to it A company’s ability to design and adjust its internal variables to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the external environment, and its ability to control the threats posed by it, determine its success [27,30]. Beside the unanimity in the literature, Dyson [31] and Mintzberg [32]; its careful implementation is the key to the strategy’s success in strategic planning. Despite the recognised importance of implementation, it is often overlooked, which may reduce the strategy’s success [33,34,35,36,37].

Similarly, the national business environment considers the same factors, but at the national level, i.e., the country in which the mining activity is carried out, being a requirement for business effectiveness and, consequently, for its strategic planning [27]. In short, the reality of the business environment is that it is increasingly complex and dynamic, where developing an understanding of the uncertainty inherent in the external environment and translating this into long-term strategic planning is a critical challenge [21]. The physical characteristics influence the development of an extraction/exploitation strategy, the budget, and the long-term plan (five-year period), and should also include a contingency plan [22]. Also important are the parameters that long-term planning should include, namely cash flows; these flows should contain information on forecast revenues, operating costs, capital costs, production, maintenance, and ore quality (content), and should also consider the effect of price, exchange rates, and inflation. It should also be noted that many minerals and metal products are sold mainly through contractual agreements with primary consumers [27]. The ability of a mining company to effectively execute an integrated business plan depends on the alignment of the activities of all participants in the company’s value chain, and it is a crucial objective of long-term strategic planning to create this alignment in a company’s value chain [23,24,25]. In short, long-term strategic planning in mining requires a flexible approach and that due consideration be given to the variability of market conditions and legislative requirements [27]. As the strategies defined by organisations are never static, managers must continuously adjust their strategies in order to anticipate and incorporate opportunities and threats from the surrounding environment [38,39]. Based on strategic planning, it is possible to predict and anticipate changes in the environment and contingent movements by competitors [40].

It is also no surprise that environmental uncertainty has been established as a critical issue in strategic management literature, as the competitive landscape has changed in recent years, faster than ever [41]. Globalisation, the rapid pace of technological development, the codification of knowledge, the Internet, the talent and mobility of employees, the increase in technology transfer rates, the continuous emergence of new rules, and the precise and rapid innovation of products and business models are factors that have contributed to the increased turbulence in the industry and, thus, the increased global level of uncertainty faced by decision-makers [42]. Recently, Haque [43] considered that the parent company’s institutional environment (country of origin) is vital in adopting environmental management standards by its subsidiaries.

Environmental uncertainty increases managers’ difficulty in understanding significant changes and how they will affect their organization [41]. This arises when managers do not have accurate information about the organizations, activities, and events in their external environment; that is when they do not feel confident that they can anticipate what the significant changes are or will be [44].

Environmental uncertainty is widely researched; for instance, Kawai e Strange [45] researched control mechanisms associated with multinationals’ autonomy and performance and their subsidiaries.

Milliken [46] explored the different types of uncertainty that strategic decision-makers can face since uncertainties can be different. He distinguished them into three specific types: the first is uncertainty about the State (when the manager does not feel able to understand or perceive how a factor in the external environment will evolve); the second is the inability of managers to predict the impact of external changes on the organisation (effect of uncertainty); the third is uncertainty associated with attempts to understand what response options are available in the organisation and their value as such (response uncertainty). Also, Dabic et al. [25] studied the impact of multinationals’ external environment, based on institutional theory. Similarly, Aguilera et al. [47] study institutional distance is also based on institutional theory.

Multinational companies often rely on regulatory institutions [25]. However, it has been found that companies facing a spiral of regulatory legislation at various levels can transfer their activities to a host country with less regulation [48] given the phenomenon of business globalisation, which allows them to operate in several countries. Thus, the institutional environment cannot be considered an independent factor for multinationals in defining and implementing their strategies [25], with institutional theory playing a predominant role in explaining this challenge [49].

Management risk has also taken on importance in organisations. It links with accounting and management control systems related to recent global events (e.g., the euro area crisis). In this context, tighter legislation has emerged worldwide (e.g., COSO—Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission) and a growing interest in corporate governance. This emphasis on risk implies changes in management control practices, assuming that the greater the risk, the greater the degree of control, resulting from the cyber control model [50].

As part of the management risk, one can also speak of the risk inherent in exchange-rate fluctuations to which multinationals/subsidiaries are subject, due to geographical dispersion. Exchange-rate fluctuations can influence a multinational and its subsidiaries’ financial performance due to the law of supply and demand, different interest rates, and inflation [51]. Generally, there are three types of foreign exchange exposures, which are: translation exposure (when exchange rate fluctuations affect the subsidiaries’ financial statements when translated into the multinational’s home currency); transaction exposure (related to cross-border transactions, in which transactions are entered into at a given time but are settled only at a future time); and economic/operational exposure (changes in the real exchange rate) [51].

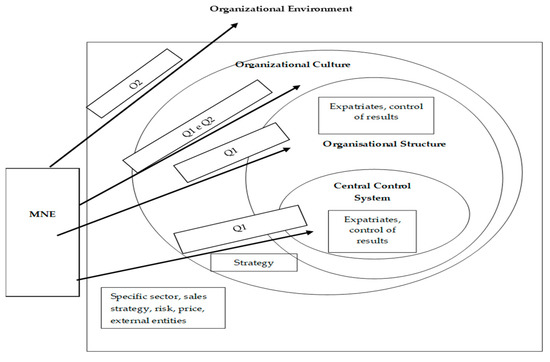

Among the various models of management control [51,52,53,54,55,56], the theoretical framework shown below was adopted (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flamholtz analysis model (1996) (Influence of the parent company on the subsidiary), adapted from Flamholtz [57,58].

As described in the previous paragraphs and in line with the research questions defined in the Introduction, we intended to analyse the management control system of the case study (a subsidiary of a Japanese multinational) based on the model of Flamholtz, Das, and Angeles [59]; Flamholtz [57,58], with the necessary adaptations to the intended objective, studied the management control system based on an organisational, cultural, behavioural, and external perspective, introducing the cultural factor with the dimensions already mentioned, but also the hierarchical culture defined by Cameron and Quinn [60], which is characterised by authority, rules and procedures, discipline, and little openness to change. It should be noted that these perspectives fit into the defined theoretical framework. These authors defined control as a set of attempts by the organisation to increase the likelihood that people will behave in a certain way to achieve organisational goals. Structure and culture are factors that have a direct influence on control. They are considered contextual controls. This model emphasises the human resources within the organisation at an individual and group level. They pointed out that this model should be used as a lens to understand, design, and evaluate a management control system, which includes several subsystems.

The central control system (the operation of which is based on the cyber approach) includes planning, operationalizing, measuring, receiving feedback, evaluating, and rewarding to enable the organisation to achieve its objectives and goals. However, Flamholtz [58] differentiated between goals and objectives, i.e., more quantitative intentions and objectives are more general intentions. Flamholtz et al. [59] concluded that there are four processes/techniques/mechanisms of control—central control mechanisms—which are planning, measurement, feedback, and evaluation/rewarding, which influence the behaviour of human resources in the organisation (individual and group), and which will bring the individual objectives of these resources in line with those of the organisation.

According to these authors, it is first necessary to define the organisational goals and objectives as inputs to the process; the measurement of results is the output/feedback that indicates how the organisation/business unit is achieving the strategic, operational, and financial goals defined; the evaluation/rewarding, which also includes feedback, is intended to motivate the behaviours of the members of the organisation/business unit to be in tune/congruent with all business units of the organisation as a whole [59]. In short, the central control system works cybernetically, with five pillars: planning, operation, measurement, feedback, and evaluation [38,39,40]. The organisational structure is composed of rules and their interpellation, differentiation, and integration. Organisations use various mechanisms such as personal supervision, the definition of procedures, job descriptions, budgets, and performance systems to facilitate people’s behaviour, as mentioned above [61].

The level of centralisation/decentralisation, specialisation, vertical/horizontal integration, and confidence in the procedures defined to solve the problems are fundamental factors for the management control system’s success in organisations. However, the organisational structure is static compared to the central control system. It is understood as a strategy to respond to market demands, technological evolution and the surrounding external environment [62], i.e., the choice of this structure is a corporate strategy focused on adapting the organisation to the mutations/requirements of its environment [57].

Organisational culture includes sharing values, beliefs, and social norms, which influence individual thinking and behaviour within the organisation. Flamholtz [57,58] pointed out that this is the starting subsystem for designing an organisational management control system. This statement is justified in that management control has to be compatible or have affinities with culture, since the latter’s dimensions influence individuals’ behaviour and have implications for the definition of the other subsystems of the control system. Not least, Flamholtz et al. [59] understood that control through culture is a form of social control, which can have an impact when knowledge of processes and performance measurement is weak; the external environment surrounding the organisation, as a contextual factor, includes new working values (increased interest in participating in decision-making), levels of professionalism, and increasing demands from clients/consumers.

This model recognises the existence of contextual variables/factors that influence the good functioning of control systems, and although it is based on the cybernetic approach, it views organisations as an open system. It emphasises the cultural and behavioural factors [59]. This conceptual model’s objective is to demonstrate that the management control system plays a fundamental role in the strategic management of a business, whether large or medium-sized. The management control system is vital for an organisation, involving all its members and influencing its strategy. The higher this involvement (individual and organisational), the more effective it will be. This system is also closely related to the alignment of the objectives and motivations of organisations and their employees, namely their vision, mission, and strategy, in order to achieve success and maximize business. The management control system encompasses two general and crucial characteristics: to function as a system that provides and facilitates information for the entire organisation and helps the decision-making process; and to seek to maximise profitability and act synergistically. These characteristics can generate conflicts between the employees’ objectives and those of the organization (dynamic tension).

In short, the conceptual model defined is based fundamentally on the following lessons:

- ⮚

- Accounting is the central basis of the model, i.e., it is this which supports the management control system, with its practices and rules, which allow all the necessary information to be obtained, so that the control mechanisms can be defined and implemented, as well as giving measurable support to the decision processes; accounting being an information system, it is understood that this is the main and most credible measurement system for an organisation. Therefore, it is fundamental for the management control system, duly conjugated with the human-resources system; accounting provides relevant and reliable information on time for the operation of the management control. These statements are corroborated by the emphasis given in recent decades to new wealth-generating factors such as information and knowledge.

- ⮚

- The central control system (Q1): a level that includes the types of control to be implemented, their operation, i.e., operational controls (implementation and monitoring).

- ⮚

- Organisational structure (Q1): this level is related to the hierarchies within the organisation, which must be appropriate to each case, adequately planned, and endowed with the flexibility necessary for the good internal functioning of the organisation; strategic management controls can influence behaviour, allowing managers to motivate their employees to implement them (setting objectives and planning).

- ⮚

- Organisational culture (Q1 and Q2): level related to the defined strategy and its pursuit, closely linked to culture, the new concept of social control, and the legitimacy it presupposes.

- ⮚

- Organisational environment (Q2): level related to external factors that directly or indirectly influence the organisation’s strategy and with consequences at other levels.

Additionally, these levels of control were studied by other authors, who investigated variables such as expatriation [19,61,62,63,64], strategy [47,65,66,67,68,69,70], autonomy [71,72,73,74], and culture [21,75], among other variables.

3. Methodology

In order to obtain evidence for the proposed research aim; namely, to get information related to the impact of the surrounding institutional environment and strategy on the MCS in a subsidiary operating in Portugal owned by a foreign economic group, the case study method was adopted, as described in the following paragraphs.

The qualitative approach (case study), common in social science and based on an in-depth investigation of a single individual, group, or event [76], was chosen to obtain empirical evidence; this method was mentioned by Langfield-Smith [77] as a relevant research approach in the management control study. This argument is supported by Piekkari and Welch [78], who argued that this approach allows for the study of all the surrounding contexts of organizations. The case under study intends to study the institutional context (external entities), the strategy, and the uncertainties (strategic and environmental) associated with managing risk and its sustainability in the MCS, i.e., various surrounding contexts, as mentioned by the authors.

On the other hand, in order to provide this case study with the credibility that this approach has implied, the methodological steps defined by Yin [76] and the topics listed by Dube e Parê [79] have been followed, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analysis of qualitative data.

In this case, in the case-study design, after the literature review, it was defined whether the variables to be studied and the research proposals were framed in the analysis model chosen and the respective proxies’ definition.

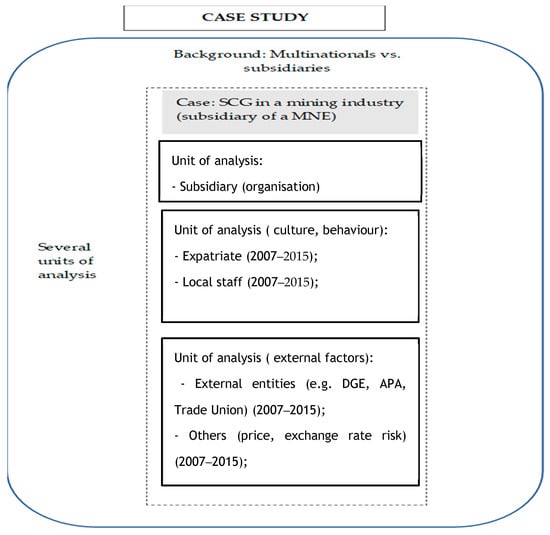

In preparation for collecting information, it was necessary to select the people to be interviewed and, posterior, to send the cover letter and the case study protocol (based on the data already collected). The collection and analysis of evidence began with the interviews and on-site observation, obtaining various documents, consulting webpages, and drawing up a final database. The case study was characterized based on the evidence collected and analysed, and the results obtained were presented and discussed, by comparison with the literature review carried out. Under these circumstances, the case study design is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Case study design (adapted from Yin [76]).

Although this is a unique case study, the analysis units are multiple, i.e., the subsidiary and the local staff’s position and the permanent expatriate on the subject to be studied and the external entities. There are several constructs subject to analysis, as shown in Figure 2.

The case-study protocol presented here is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Case-study protocol.

Thus, based on the interview script prepared, the three local administrators, one expatriate administrator, five local directors, and one person in charge, whose experience in the subsidiary was significant, were interviewed. These interviews lasted an average of one hour and thirty minutes. They were written by the interviewer and, at a later stage, sent via e-mail for final validation by the interviewees.

Table 3 presents some characteristics of the Portuguese extractive industry, with the data for 2014 being the most recent information available from regulatory authorities.

Table 3.

Characterization of the extractive industry in Portugal.

The extractive industry in Portugal is also considered strategic. It is usually located in inland regions of the country, and its activities generate wealth and create jobs locally and contribute to regional economic and social development [80,81].

Turning now to the sectoral context in which the subsidiary under analysis is included, and the case study’s description, all relevant information is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sectoral context and description of the case study.

The mission of the subsidiary under review, according to a formal communication to the employees of Director X, is the following: “We are a mining company focused on the discovery, extraction, and concentration of minerals, dedicated to transforming these natural resources into wealth and Sustainable Development, committed to maximizing value for our shareholders, customers, and all stakeholders, creating local opportunities that sustain the progress of the local economy, increasing the safety, health, well-being and environmental and social awareness of our employees.” Regarding the company’s vision, he explained that, “Our Vision is to continue to be a Company in the Extractive Mineral Resources Industry, highly respected in the country and leader in the production of wolfram concentrate in Portugal.” Regarding its strategy, administrators X and Y argued, “Our strategy is to operate at low cost the mine that has a vast potential to increase life time, using the most modern and appropriate skills and technologies available, adopting modern production and business management techniques and selling the products produced to a diversified market. We are focused on increasing our reserves and mineral resources to maintain a long life of this asset of ours, continue to create and distribute value to our shareholders and the local community, and continue to satisfy our customers’ needs. Our products are necessary raw materials to sustain today’s international growth and the growth that will occur over a long period from now on. We believe that, in the long term, increasing industrialisation will continue to drive demand for the metals we produce”.

Regarding external entities and external factors, their description is reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

External entities and external factors.

It is important to note that the subsidiary under review is a lode mine, where wolfram (a source of tungsten) is the main ore extracted. Mining is carried out using chambers and pillars. The mine is vertically divided into four structural levels; for each level, a grid of base galleries, five metres wide, is defined; at the points of intersection (between the dismounts and the levels), chimneys are opened for the vertical transportation of the ore. Exploration begins with the construction of spiral ramps or exploration galleries to gain access to the rows identified in the boreholes; then the pillars are constructed so as to allow a theoretical recovery of eighty-four per cent of the row; then the detonations are carried out at the identified locations, whose stone is then loaded into the chimneys to the central belt, which transports the earth to the launderette, where the final concentrate is produced and evaluated. Given the rarity of this typology of mines, they cannot be compared to the many open-cast mines or in mass (the minerals are not concentrated in the lode) (administrators X and Y).

4. Results

In response to research question 1 (Q1), Director Z said, “Beralt’s organisational culture is different from the motherhouse because the cultural influences are very different; the Japanese like everything to go according to plan, not liking last-minute changes or surprises, now as we know, the Portuguese are no longer like that! Thus, the local organisational culture is based on Portuguese culture and mainly on the subsidiary’s historical culture. This cultural constraint also implies in itself that the control of results is tighter.”

Director B considers that the subsidiary’s existing organisational culture has not undergone any change in relation to the culture of the country of origin of the parent company and inherent to the shareholder and that if there are disparities in this regard, he always tries to overcome them. However, he believes that the shareholder’s lack of mining tradition has more impact on the local organisational culture than his country’s culture.

The organisational culture related to the way in which mining was carried out until 2007 has changed in the light of the parent company’s guidelines; however, this has had no influence on the organisational culture intrinsic to the subsidiary (Director X).

Finally, Director T understands that the subsidiary’s organisational culture is closely linked to the local community/culture, because “The mine and the company’s industrial area are located within the locality where the operations are carried out. In other words, the locality, namely its well-known mining district, was built to house the miners who then worked in the company,” giving some particular examples. This sums up this variable as something sui generis, i.e., “That is a family,” and, from a personal point of view, “One of my concerns is to clearly understand what organisational culture has a company where I am and what the different administrations and/or directors to whom I have reported/report expect from my person or the department I run. This is fundamental” and always seeks to be aligned with the organisational objectives set by the shareholder. The shareholder and, logically, the permanent expatriate, do not adapt to the subsidiary and local culture, and their management style has not been modelled according to their specific characteristics, which does not corroborate the conclusions of Giraud et al. [17] and Icfai [54]. According to the latter authors, control was exercised only as a technique, not taking into account the subsidiary’s culture, and based their system on the cultural controls of the Jaeger and Baliga [16]. Giraud et al. [17] also studied the culture of managers and its influence on control, in which the parent company must understand the culture of the host countries, and this is not the case in this study. From another perspective, local culture does not directly influence the subsidiary’s staff and is null and void on the shareholder.

As explained in Table 5 (Q2), price and exchange rate risk are external factors that directly influence and condition the subsidiary’s strategy and performance. The influence of these factors is recalled by Smith [19], although in this case, the price had a more significant impact than exchange rate fluctuations.

In the subsidiary under analysis, the price has a high weight, as the Expatriate Administrator states when arguing that the “quotation directly impacts the result/sales. We have experienced these years fluctuations in price, which have implied sales decreases of 50% for the same quantity produced.” More explicitly, Administrator X states that “These parameters he mentions are the greatest concern of the company and my function. The fluctuations in the market price and the exchange rate between the US dollar and the euro condition the stability of the activity and strategic decisions of the parent company and the company,” in which these fluctuations have an impact, in the short term, on the cashflow of the subsidiary, leading to further requests for clarification by the parent company, since it had to finance the subsidiary in recent years in order for it to remain in business. A long-term analysis involved more in-depth management work between the subsidiary and the parent company. All possible scenarios were analyzed, including the mine’s closure and sale, the latter having been the decision taken. In short, Administrator Y illustrates the weight of this variable, saying that, “In short, it affects!”; and “The fact that the shareholder did not control the price and had to sell below cost price in order to fulfil their local/government commitments, led to the strategic decision to sell the subsidiary, but it took years to make this decision, which came to a head as soon as the price fell and the subsidiary had to be financed by them.”

Since this variable has a significant effect on the subsidiary’s financial statements, Director Z assumes that it can have both negative and positive effects over which the subsidiary has no influence, since the price set by two speciality magazines, in which China’s overproduction has had a significant weight (the world’s largest producer), has suffered negative oscillations; however, with these oscillations, Director Z argued that “… this situation has a great impact on results, forcing the parent company to finance the operations over the last five years. This situation (among others of lesser impact), very contrary to the initial expectations of the shareholders, who expected in the short term to draw good dividends for the liquidation of the loan they requested to acquire us, led them to put the subsidiary up for sale in mid-2014.”

In short, price is an external macroeconomic factor that directly affects the subsidiary’s financial performance and stability and strategic decisions. In recent times, the price of wolfram has suffered sharp declines, which has led the parent company to conduct a rigorous market analysis in order to make decisions regarding the future of the subsidiary, since its activity is continuously being financed by them, and since the cost price is higher than the selling price, which has led to adjustments in production and an inherent decrease in sales and, consequently, high losses. Thus, the subsidiary is no longer a strategic investment for the shareholders, which led to it being sold at the end of December 2015. This means that a quick and dynamic adaptation to the surrounding environment and uncertainty is necessary [9,12].

Thus, it can be argued that the parent company faced a problematic price change for eight years, which generated enormous environmental uncertainty [41,42] generated by market volatility and turbulence, making it difficult for managers to foresee the scenarios their companies will face. Duncan [44] said that this was inherent to managers precisely because of the constant and rapid change in their organisations’ external environment. Another author [46] defined the types of uncertainty experienced by managers applied to this case study. Thus, the local managers of this subsidiary face uncertainty about the State (they cannot predict the evolution of the price), the effect of uncertainty (they do not know how long it will take), and the uncertainty of the response (they do not see, in the short term, the responses that the parent company may have to face this uncertainty), as explained by Milliken [46].

Regarding the exchange rate risk, “The parent company is a foreign company, so it pays attention to the variation in its country’s currency. In this sense, we pay attention to the variations in the exchange rate of the dollar, the euro and the yen, which has an impact on the subsidiary’s accounts,” according to the Expatriate Administrator. Since the ore sales are made in US dollars, this risk was mitigated. “At the beginning of the budget preparation, the parent company informs us of the exchange rate that we should consider for the following year. If the exchange rate evolution is unfavourable to us, the exchange of US dollars for euros is made on a spot basis or in the concise term (maximum seven days). If the exchange rate falls below the reference rate (i.e., favourable), the subsidiary should negotiate one or more forward contracts with the banks up to the limit authorised by them. The amount to be negotiated must correspond to 60% of the estimated sales (for the next quarter or semester) in order to be able to accommodate eventual decreases in the wolfram price,” according to Director Z.

Exchange-rate fluctuations are also an external macroeconomic factor influencing the company’s financial performance and strategy. They directly affect the subsidiary and the parent company. To minimize these fluctuations, financial instruments such as spot or forward contracts are used, based on the parent company’s exchange rate fixed in the annual budget. This confirms the foreign-exchange risk inherent in the transactions carried out by the subsidiary, specifically the transaction risk [50].

Although there is a risk-management policy in place at the parent company (Table 5), this was not sufficient to control/respond to/avoid the risk inherent in constant price fluctuations, which implied constant changes in strategy for the subsidiary, culminating in its sale, anticipated by more significant and more demanding control [50]. Concerning exchange-rate risk, this was minimised employing market financial instruments.

Table 5 also describes the competencies of external entities involved in this activity that cause some discomfort and difficulties in pursuing some of the goals and purposes defined for the subsidiary and, to some extent, impacting its strategy. At the national level, this institutional and/or business environment generates some environmental uncertainty, as several authors have mentioned [25,27,41,44,82,83].

First of all, “The parent company pays much attention to its responsibilities concerning legislation, such as taxes, environment, labour, safety and mine closure. This has been the most common trend so far that the parent company has decided to reduce investment,” stresses the Expatriate Administrator. This statement is reinforced by Administrator X and Administrator Y, who conclude that the parent company has “…very much in mind…” the sector’s regulatory bodies and Portuguese legislation, and wants to be informed about all the matters and steps taken with them, although it does not get involved or participate in the meetings. In general, Administrator Y assumes that “These entities do not command, but create problems. The union is contagious to the local community with the encouragement of strikes, affecting its image. The DGEG has created problems at the environmental permit level, a matter which is being resolved by the head administrator. “It is silent on the standard report to be sent—standard report for mineral resources and mineral reserves—so there is no uniformity in the reports made by the different mining projects at the national level.”

Furthermore, this entity does not have a qualified and internationally recognized personnel for this monitoring type. On the other hand, according to its functions, this entity understands that it carries out “… inspection actions…” with the objective of “… verification of the various legal requirements, technical support whenever requested, and monitoring of the activities developed in the mining concession.” The parent company’s culture did not influence the performance of its functions, as they always implemented according to its recommendations.

The APA is another external entity with institutional relations with the subsidiary concerning environmental issues. It has already been perceived that it has exerted pressure to solve existing problems in this area.

The union also exerts some external pressure through the workers, reflected in the human resources policy, by always presenting “…a demand notebook for the following year…” and by making various expositions to the authority for working conditions regarding issues denounced by the workers, according to the Responsible B. According to this officer, the trade union puts pressure on the subsidiary because the problems are solved when they arise, that is, it is necessary to “…implement a preventive problem-solving policy…,” and also gave as an example its strong contestation when the Code of Ethics and Conduct was disclosed, because the workers had to sign a declaration.

In short, the parent company’s relationship with external entities is clear-sighted in the following expression by Director B: “I think that they do not have a proactive attitude to the situation to avoid external and internal conflicts. As for the regulatory entities, the shareholders only have contact with them since they put the subsidiary up for sale because this is a concession and they had a strategic interest in getting the agreement for sale.”

By analysing all the interviews together, we can conclude that external entities and their legislation are important to the parent company. However, it is not involved in contacts with them, requiring it to be adequately and timely informed through all negotiations and agreements made with them through the expatriate. Specifically, DGEG and the APA have created difficulties in obtaining the environmental permit, and STIM damages the company’s image and contagions employees and the local community. Given the lack of Portuguese legislation for the determination of reserves and mineral resources, the parent company feels free to pressure the subsidiary to present to the DGEG the figures considered convenient by them, which is possible due to the absence of regulations and qualified personnel to give an opinion on this determination.

The external entities mentioned are exerting some pressure on the subsidiary. For example, depending on the APA to obtain the environmental permit, the DGEG has a less predominant role regarding the operating permit, and the trade union exerts pressure on the attitude of workers towards decisions taken and media communications. Thus, it is clear that these are part of the subsidiary’s institutional environment [25]. However, through its expatriate, the group did not know how to deal with these pressures and preferred to delegate these institutional relations to the local frameworks.

It is crucial to consider the role of external entities in the mining industry’s strategy, which, to some extent, has not been adequately considered by the group [27]. The company’s headquarters did not pay adequate attention to its external environment, which was reflected in its autonomy and performance [81].

Ultimately, we have the strategy of the subsidiary. Smith [19] argued that an ore mining company’s strategy is based on its resources and mineral reserves in the medium and long term, so the subsidiary strategy should also be based on this and thus contribute to value creation.

In this case, Administrator Y understands that “The group’s overall strategy has always been, and continues to be, to place this ore in its country of origin, since it had commitments to the government, as such, always financed the companies activity at the most critical moments. Thus, the sales strategy involves selling all products to customers in that country regardless of price, based on the official quotation. Hence the need for financing has worsened since the official quotation for this ore has suffered significant falls in recent times, which has not been compensated by the increase in production due to the low content (improvements in content).” This opinion was also shared by Director X.

More directly, the Expatriate Administrator states that “…there is no defined strategy for the subsidiary…,” although the parent company has long-term strategic planning, which included the acquisition of this subsidiary. At present, its objective is to recover this direct investment as soon as possible. It also points out that the MCS in the subsidiary does not minimize the strategic uncertainty associated with its activity, but makes no comment on the fact that the cultural differences between the country of origin and the host country and its relations with China influence the strategic vagueness experienced by the subsidiary for eight years, having only said that China is the largest producer of this minerals. For administrators X and Y, China’s expansion has contributed to raising commodity prices and causing some intense fluctuation in international markets, which causes economic instability for companies that exploit these resources.

In this context, the strategic planning for the subsidiary is only short-term, according to Administrator X, who explains that this is linked “…to the quantities of ore that the market can absorb at each moment…,” where this market is unstable due to the “…quantities produced in China’s everyday operations.”

It should be noted that we are discussing a subsidiary 100% owned by a Japanese multinational that considered it, at the time of that acquisition, a strategic investment, given its final product and given the relations of the country of origin with China (the largest producer of this ore), to gain a competitive advantage [22].

The strategic planning of the extractive industry is directly related to its production capacity concerning the estimated mineral resources and reserves at each moment, always bearing in mind that it is a lode mine, as explained by Administrator Y. Thus, this planning begins with the calculation of this estimate, for which there is no standardized and legislated method, so Director W understands that “There is great influence from the parent company…,” which implies that “…the parent company controls the information disclosed and prevents by confidentiality safeguards the disclosure of these results…”; as to the management risk or uncertainty involved in these estimates, this director considers that this is inherent in the very definition of mineral resources and reserves, however, “… there are no capable regulatory authorities—he will always use the one that suits him best…,” referring to the parent company.

Another parameter that contributes to the definition of the strategy and its planning is the ore content, as well as the control of avoidable losses from extraction, so several strategic and operational controls have been implemented (e.g., the pint, the cutting height, the handles), as mentioned by Director T.

In this type of industry, research and development activity is crucial (ground surveys) and has an impact on the strategy to be defined, but, “The existing research is the strictly necessary one because the parent company does not invest in this fundamental area for mining activity,” according to Director B, because the degree of risk and strategic uncertainty is high, the costs are also high. The return is not immediate, so it is essential to have financial resources available, as Director T explained.

Director Z explained that “After the acquisition of the subsidiary by the group, an attempt was made to implement five-year strategic planning by drawing up an investment plan in fixed assets (including mining equipment), a drill plan both inside and outside the concession area to find patches that would be economically viable (either inside the mine or outside the mine—in this case, that would allow for the possibility of opening a new mine) accompanied by the preparation of five-year financial demos. This was only an attempt because of the unfavourable price and exchange rate developments, which forced the subsidiary to define annual plans only.” He assumes that this reflects how the parent company exercises control and executes the MCS, since “The parent company has a great influence on the MCS of the subsidiary, not only because of the presence of the expatriate(s) but essentially because of the almost daily demand for answers to practical questions or the sending of questionnaires on the most diverse areas (internal control, taxation, information systems) and that its monitoring is constant.”

All this strategic uncertainty was reflected in the subsidiary’s financial performance, notably by increasing group loans and the results. The subsidiary’s financial situation was also illustrated in several journalistic articles in 2015.

So, it can be considered that:

- ⮚

- The parent company’s strategy is defined as it buys all the former’s production because its final product is a strategic mineral for it. However, strategic production planning and resource allocation is the subsidiary’s responsibility since the parent company is unaware of lode mines, but always lacks the parent company’s final approval. Even then, it is always being altered by instructions from the shareholders. Strategic planning is always short-term because it is always associated with the market’s absorption with unstable characteristics originated by the informal productions in China and variations in the mineral price and mineral content. In its strategic decisions regarding the subsidiary, the parent company does not consider the subsidiary’s specificities, understanding that it is challenging to minimise strategic uncertainty because of the weight that Chinese production assumes in this ore market. This strategic uncertainty may be related to the culture of the country of origin.

- ⮚

- The strategic planning of the subsidiary is determined by the discharge of the mineral resources and reserves of the mine, over which the parent company has a direct influence, since there is no Portuguese legislation on the determination of such, leading to the results presented being controlled by it and determined by economic interests, and not corresponding to reality. This manipulation of the estimated mineral resources and reserves involves high risk and alters the strategies to be defined. There are also no strategic and operational controls on the determination of such resources and reserves, due to the lack of financial means, which implies that the uncertainty of the information is high and the risk assumed by the parent company is excellent, leading to the credibility of that information being questioned. Also important is the research and development activity, whose investment by the parent company has fallen far short of the subsidiary’s expectations and needs, influencing the strategy defined.

- ⮚

- Another essential factor for the strategy is the maximisation of production, and its content, so strategic and operational controls are relevant to the absence of avoidable losses. These controls are technical, and management controls are inherent to a seam mine.

- ⮚

- Regarding the human-resources strategy integrated into the subsidiary’s overall strategy, the parent company defines it according to the strategic planning of production.

- ⮚

- Regarding the influence of the MCS strategy, the parent company tried to implement long-term strategic planning. However, variations in ore prices and exchange rates did not provide the subsidiary with the necessary liquidity to make it viable. Thus, the subsidiary operated from 2008 to 2015 with annual strategic plans. This implementation would require the MCS’s outputs to be adapted in terms of information and maturity changes.

As implied by the previous presentation, the relations between the subsidiary and the parent company concerning the strategy were fragile and did not allow cultural barriers to be overcome [25]. This subsidiary’s case study showed a high degree of strategic uncertainty, implying that the shareholder makes choices at various levels [3]. Of course, this choice influences the MCS understood as supporting them and dynamic [3].

Smith [19] also admitted that the mining industry strategy is linked to the MCS, this also being the opinion of Director Z. Of the strategic control mechanisms implemented, that of the ore content, to which this subsidiary pays extreme attention, is crucial [27,84,85]. The same authors also advocate the definition of operational controls (e.g., cashflows) as necessary in defining strategic planning, and these are implemented in the subsidiary.

The integration of the inputs from all departments, through their directors, is indispensable for this planning [27], a situation found to exist in this subsidiary.

Without minimizing these positive aspects existing in the subsidiary, the parent company did not have a long-term strategy defined for the subsidiary. However, only short-term planning (annual budget) was carried out, contrary to Smith [19]. However, the author also pointed out that external factors must be taken into account, but not only that the parent company only considers these as mentioned in the various quotes from local management, which has always led to constant changes in the short-term strategy, and is unable to predict the changes and their long-term impacts, including environmental uncertainty—[46,47,49,50].

In view of the management control system in the subsidiary analysed in the light of the Flamholtz [58] model, it is argued that there is a central control system, albeit with some nuances. However, it works and allows the parent company to exercise its control in all departments through the inputs required from them, so that the financial department responds to their demands. The organisational structure is vertical and appropriate to the degree of control exercised by the parent company, according to Director T. The subsidiary’s organisational culture has not changed. However, its local staff has had to adapt their behaviour to the parent company’s culture of origin. However, the subsidiary’s strategy reflects the parent company’s market culture [18] but has not been able to circumvent the uncertainties inherent in the organisational environment. Therefore, we can conclude that the model adopted can be applied in this subsidiary by introducing several improvements, mainly involving the shareholder’s attitude.

This model’s application to this case study corroborates the management control system’s purpose, through the central control system level, of Langfield-Smith [77] and Widener [70]. There is also an influence on local staff’s behaviour concerning the parent company’s culture [82], through the placement of a permanent expatriate in the subsidiary’s organisational structure.

From another perspective, the parent company was unable to implement a sustainable long-term strategy for the subsidiary (level of organisational culture) because it could not manage the risk of external factors (e.g., price evolution) and external entities, i.e., the subsidiary’s organisational environment. This means that the management control system was not a vehicle for sustaining the strategy [1] and for managing the opportunities and threats [66].

Finally, the parent company’s control of the subsidiary, reflected in the subsidiary’s control system, does not show good and effective integration of both parties [4,70], reflecting on interpersonal relations with the permanent expatriate.

So, we can conclude that this model has made it possible to study the subsidiary’s management control system, taking into consideration parameters such as the culture and behaviour of its local and expatriate managers [57,58,59], in which, in this case, there is a market culture and also hierarchical inherent to the country of origin of the parent company, with the characteristics defined by Cameron and Quinn [60].

5. Discussion: Strategy, Management Control System of a Foreign Subsidiary, and Open Innovation

For most companies, research and development (R&D) meant the possession of a strategic resource, which acted as a barrier to entry for other competitors [83]. However, the subsidiary analysed here has a very specific production process (tungsten in a lode mine) that is unknown to many other companies in the extractive industry. This is apparent from the unanimous response of those interviewed—total ignorance of the operation and planning of a lode mine’s operations—when asked about the shareholder’s knowledge of this process. In addition, the shareholder’s main activity is not mining, this was only a strategic investment supported by their country of origin, so R&D investment is scarce, as mentioned by Director T. It is then realized that the effectiveness of innovation is heterogeneous among companies and is directly related to business models and the way strategies are implemented [84]. It is also seen in this subsidiary that the expatriate director has an imposing attitude to absorb knowledge and share it with the shareholder, whereas the transfer of knowledge to the subsidiary is null, which led to arguments by Ahn et al. [85] that the knowledge of different actors is important for the development and exploitation of open innovation, which is a predictor of better economic performance and greater resilience.

From another perspective, as this activity generates negative impacts on the environment, it is important that managers and directors assume a sustainable attitude, through the co-creation of social value, in addition to economic value, because, as De Silva and Wright [86] suggested, it is important to develop entrepreneurial attitudes that generate social impacts sustained in open-innovation approaches (e.g., co-creation). It is clear that the expatriate administrator made clear the importance of culture in his country of origin, which conditioned his full integration in the subsidiary and in the local mining community, although Yun et al. [85] considered that culture plays an important role in promoting a dynamic and open culture for innovation.

Against this background, this evidence suggests a fertile field for future research into open innovation in the extractive industries.

6. Conclusions

This case study was based on the premise that the organization is an open system, with internal (parent company) and external (external factors and entities) influences. It was confirmed that the subsidiary’s management control practices resulted from the parent company’s requirements (for instance, placement of a permanent expatriate), affecting local staff’s behaviour.

Considering the proposed research objectives to obtain further information on how the parent company influences the MCS of the subsidiary (in the cultural and organizational dimensions), it can therefore be concluded that the parent company exercises influence over the MCS of the subsidiary since it has been able to implement continuous (daily) controls, both financial and operational. On the other hand, the appointment of an expatriate as a trustee was intended to exercise that influence, but the control exercised by the latter did not take account of the cultural differences between the two parties, giving rise to dynamic tensions.

Regarding the research aim related to exploring other factors that influence the subsidiary’s MCS (external entities, price, risk, strategy), it is also noted that external factors and external entities do not directly influence the MCS, but rather the subsidiary’s strategy. These are materialised in its short-term strategic planning only, although academia argued that the strategy’s sustainability is based on the MCS. Thus, the parent company could not implement a long-term sustainable strategy for the subsidiary (level of organizational culture), since it could not manage the risk of external factors (e.g., price evolution) and external entities, i.e., the subsidiary’s organizational environment. This situation led us to conclude that the MCS was not a vehicle for sustaining the strategy and managing the opportunities and threats. In its relations with the institutional environment, the parent company has delegated these functions to local staff, with the sole aim of complying with the legislation, i.e., it did not intend to create any added value.

Finally, the subsidiary’s strategy reflects the parent company’s market culture but has not been able to circumvent the uncertainties inherent in the organizational environment [86]. In short, the parent company influenced the MCS of the subsidiary. It changed the way control was exercised in it but was unable to deal with macroeconomic instability, environmental and strategic uncertainty, and, consequently, with the management risk involved in the mining activity, because this subsidiary exploited a seam mine and was unaware of it since it is essentially an economic trading group.

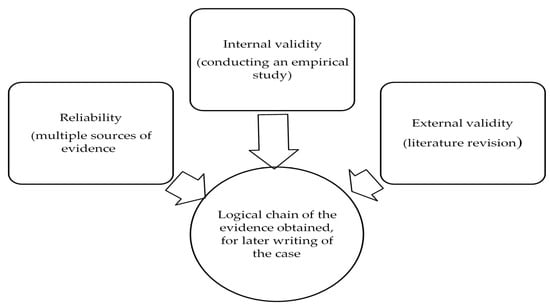

However, this case study has some identified limitations. The first is that it is a unique case, which provides in-depth information, but further research should be pursued so that these results can be compared with other case studies. Second, the chosen case belongs to a particular sector that, as already highlighted, provides a wealth of information on this specific activity sector. Third, it was not possible to interview the head of the parent company. No response has been obtained from the Mining Industry Workers Union, although steps have been taken to this end. These limitations are significantly inhibiting to a comparative analysis of the MCS with other types of industries, which does not minimize its internal and external validity, due to the use of multiple sources of information and its crossing with scientific knowledge (Figure 3), and also due to the requirements that any MCS must obey, being similar in all industries, with the due adaptations to its activity. Additionally, the fact that the staff at the corporate headquarters were not included in this study has been turned by the expatriate administrator’s re-assignments, which reflect their culture and the culture of their country of origin (Japan).

Figure 3.

Principles adapted of Yin [76].

Despite the limitations, some contributions are also identified. The first relates to the fact that an extractive industry has been studied, the end product of which is strategic for Europe and the world, namely for the country of origin of the capital studied. The third, and more generic, is the presentation of a study on the extractive industry in the area of management in Portugal since all current academic work focuses on the area of geology and exploration itself.

In addition, the innovation process, when shared with other actors, generates mutual benefits for those involved. In this case, between subsidiaries and headquarters (MNE), it is important to adopt an open innovation transfer processes to acquire knowledge, organise resources and skills, and sustain their strategies in the long term. This means that the association of open innovation with MSC is a fertile avenue for future research.

For future research, a study analysing the effect/relationship of the variables studied in this case study is suggested, including the changes that have occurred in the company’s share capital due to the shareholders’ nationality. A multiple case study on the MCS in the three primary Portuguese mines is also suggested to make a comparative analysis. Finally, an interesting research topic would be replicating this study in all the geographically dispersed mines belonging to the current multinational corporation holding the subsidiary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.R., M.d.C.A. and R.S.; methodology, M.R. and R.S.; software, R.S.; validation, M.R. and M.d.C.A.; formal analysis, M.R., M.d.C.A. and C.O.; investigation, M.R., M.d.C.A., J.V., C.O. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., M.d.C.A., J.V., C.O. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, M.R., M.d.C.A., J.V., C.O. and R.S.; visualisation, M.R.; supervision, M.R. and M.d.C.A.; project administration, M.R., M.d.C.A., C.O. and R.S.; funding acquisition, M.R., R.S., C.O. and J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of the author Rui Silva is supported by national funds, through the FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the project UIDB/04011/2020. The work of the author Cidália Oliveira is financed by NIPE (Centre for Research in Economics and Management), University of Minho, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro and CETRAD (Centre for Transdisciplinary Development Studies) and NIPE (Centre for Research in Economics and Management), University of Minho, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gond, J.-P.; Grubnic, S.; Herzig, C.; Moon, J. Configuring management control systems: Theorizing the integration of strategy and sustainability. Manag. Account. Res. 2012, 23, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, H.; Oakes, S. An Overture for Organisational Transformation with accounting and music. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2019, 64, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.F. Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 529–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppmann, A.H. INTERACTIVITY—Control Mechanism or Management Tool? Copenhagen Business School: Frederiksberg, Danmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Samiee, S.; Theodosiou, M. Strategy fit and performance consequences of international marketing standardization. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.P. Social control or bureaucratic control? -The effects of the control mechanisms on the subsidiary performance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.A.M. Abordagem Histórica e Institucional da Mudança em Contabilidade de Gestão: O Caso da Normalização nos Hospitais Públicos Portugueses; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Bower, J.L. Customer Power, Strategic Investment, and the Failure of Leading Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 17, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, H.; Pohjola, M.; Olkkonen, R.; Koponen, A. Dynamic capabilities and firm performance in a financial crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2707–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.M. Revisiting an identity-based view of sustainable competitive advantage. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C. What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.D.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Dual capabilities and organizational learning in new product market performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 46, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, A.J. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Orv. Hetil. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, A.; Baliga, B. Control Systems and Strategic Adaptation: Lessons from the Japanese Experience. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, J.M.F.; Zarlowski, P.; Saulpic, O.; Lorain, M.-A.; Fourcade, F. The Art of Management Control—Issues and Practices; Pearson: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Übius, Ü.; Alas, R. Organizational Culture Types as Predictors of Corporate Social Responsibility. Engineering 2009, 1, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.I.; Choi, J. Control mechanisms of MNEs and absorption of foreign technology in cross-border acquisitions §. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.I.; Glaister, K.; Oh, K.-S. Technology Acquisition and Performance in International Acquisitions: The Role of Compatibility between Acquiring and Acquired Firms. J. East. West. Bus. 2009, 15, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, J.-E.; Vahlne, I. Technology integration through international acquisitions: The case of foreign manufacturing TNCs in Sweden. Scand. J. Manag. 2002, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargos, M.A.; Barbosa, F.V. Fusões e aquisições de empresas brasileiras: Criação de valor e sinergias operacionais. Rev. Adm. Empres. 2009, 49, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bratianu, C. Intellectual capital research and practice: 7 myths and one golden rule. Manag. Mark. 2018, 13, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Bejinaru, R. The Theory of Knowledge Fields: A Thermodynamics Approach. Systems 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabic, M.; González-Loureiro, M.; Furrer, O. Research on the strategy of multinational enterprises: Key approaches and new avenues. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerras-Martín, L.Á.; Madhok, A.; Montoro-Sánchez, Á. The evolution of strategic management research: Recent trends and current directions. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L. Strategic long term planning in mining. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2012, 112, 761–774. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, S.G.; Finkelstein, C.E.; Mitchell, S.; Peteraf, W.; Singh, M.A.; Teece, H.; Winter, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, D. Capability reconfiguration: An analysis of incumbent responses to technological change. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bititci, U.S.; Martinez, V.; Albores, P.; Parung, J. Creating and Managing Value in Collaborative Networks. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2004, 34, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, R.G. Strategy, performance and operational research. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2000, 51, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. The design school: Reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.D. Successfully implementing strategic decisions. Long Range Plann. 1985, 18, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, C.J.F.; Santos, S.P. Strategy implementation: What is the failure rate? J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The strategy map: Guide to aligning intangible assets. Strateg. Leadersh. 2004, 32, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankins, M.C.; Steele, R. Turning great strategy into great performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sterling, J. Translating strategy into effective implementation: Dispelling the myths and highlighting what works. Strateg. Lead. 2003, 31, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokins, G. Driving Acceptance and Adoption of Business Analytics. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2013, 24, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokins, G. Enterprise Performance Management (EPM) and the Digital Revolution. Perform. Improv. 2017, 56, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C.A. Putting leadership back into strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiato, R. Creating value through foresight: First mover advantages and strategic agility. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 101, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Strategic planning in a turbulent environment: Evidence from the oil majors. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. Determinants of Environmental Standards Adoption by Multinational Corporations: A Review of Extant Literature; Non-market Strategies in International Business; Shirodkar, V., Strange, R., McGuire, S., Eds.; The Academy of International Business Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R.B. Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Strange, R. Subsidiary autonomy and performance in Japanese multinationals in Europe. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J. Three Types of Perceived Uncertainty about the Environment: State, Effect, and Response Uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Rugman, A.M. Differentiated effects of formal and informal institutional distance between countries on the environmental performance of multinational enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Snidal, D. Taking responsive regulation transnational: Strategies for international organizations. Regul. Gov. 2013, 7, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupo, R.; Martin, G. Dynamics of The Evolution of The Strategy Concept 1962–2008: A Co-Word Analysis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 162–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soin, K.; Collier, P. Risk and risk management in management accounting and control. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmi, T.; Brown, D.A. Management control systems as a package—Opportunities, challenges and research directions. Manag. Account. Res. 2008, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]