Exploring Perceptions of Sustainable Development in South Korea: An Approach Based on Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Belief System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development Policy

2.2. The Advocacy Coalition Framework and Hierarchical Belief Systems

2.3. Perception of Sustainable Development

2.4. Synthesis of Theoretical Background and Literature Review

3. Research Design

Q Methodology

4. Analysis

4.1. Outline of Q Analysis

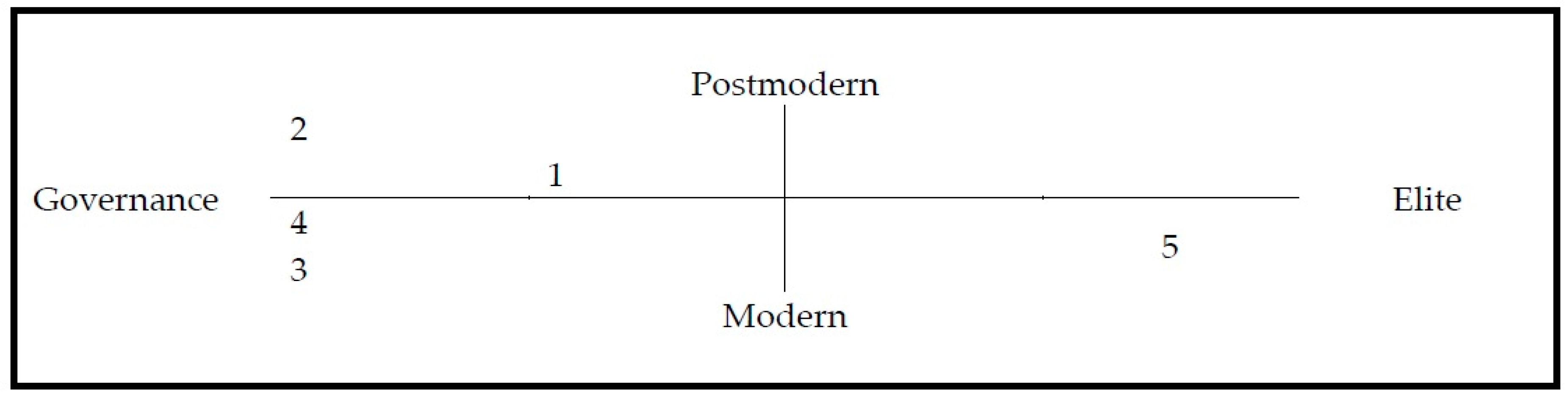

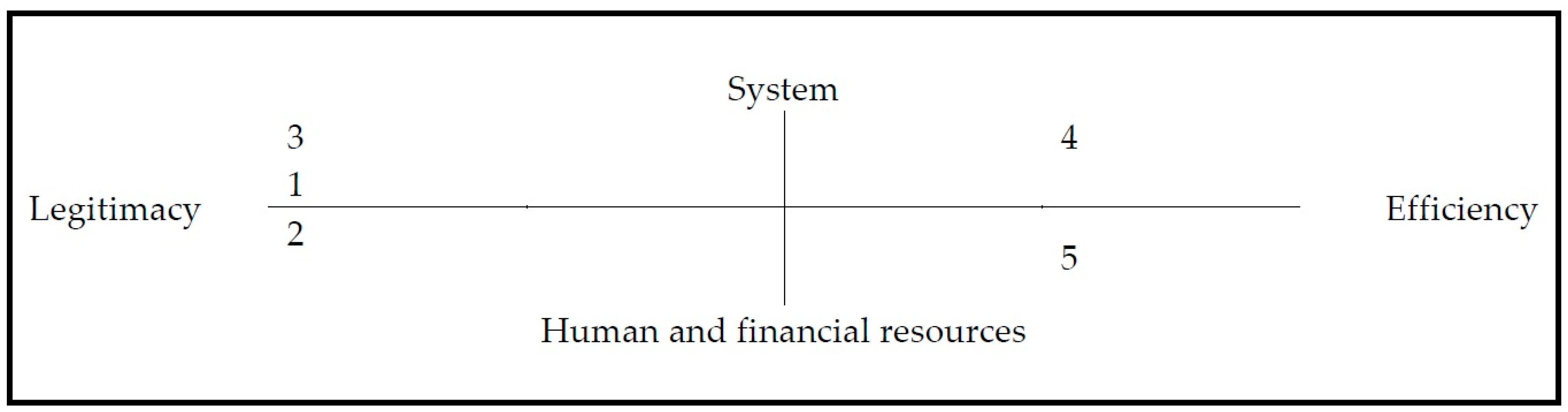

4.2. Characteristics of the Five Respondent Types

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated. 2007. Available online: http://eureka.sbs.ox.ac.uk/761/1/Social_Innovation.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Polit. 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jung, K. Exploring institutional reform of Korean civil service pension: Advocacy coalition framework, policy knowledge and social innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Complex. 2018, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dey, A.; Singh, G. Connecting corporations and communities: Towards a theory of social inclusive open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Complex. 2017, 3, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J. Open Innovation: Technology, Market and Complexity in South Korea. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2016, 21, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J. How do we conquer the growth limits of capitalism? Schumpeterian Dynamics of Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Complex. 2015, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2018. New York: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2018. Available online: http://www.sdgindex.org/reports/2018/ (accessed on 26 July 2018).

- Climate Action Tracker. Improvement in Warming Outlook as China and India Move Ahead, but Paris Agreement Gap Still Looms Large. November 2017. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/documents/61/CAT_2017-11-15_ImprovementInWarmingOutlook_BriefingPaper.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- UN Sustainable Development Center Opened. Financial News. 15 June 2012. Available online: www.fnnews.com/news/201206081513278895?t=y (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Ministry of Environment’s Sustainable Development Committee Promoted to Presidential Committee. Yonhap News TV. 26 May 2017. Available online: www.yonhapnewstv.co.kr/MYH20170526018200038/?did=1825m (accessed on 12 October2018).

- Jaegal, D.; Park, T.-J.; Che, J.-H. Citizens’ perceptions of the sustainable development policies of local governments. Korean Repub. Adm. Rev. 2004, 38, 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.-J.; Won, G.-Y. Social acceptance of Lee Myung-bak’s green growth-based climate change policy regime: An evaluation based on a survey of experts’ perceptions. ECO 2012, 16, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.-G.; Kang, S.-D. Public perceptions of sustainable development in South Korea: A comparison among members of government, industry, and NGOs. Bull. Inst. Bus. Econ. Res. 2015, 35, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, W. The Study of Behavior; Q-Technique and Its Methodology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K. Relevance and applicability of Q methodology in political science. J. Korean Stud. Inf. Serv. Syst. 2003, 8, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Council on Sustainable Development. Government Officials’ Perception of Sustainable Development; Presidential Council on Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- World Commission on Environment and Development [WCED]. Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Ekins, P. Economic Growth, Human Welfare, and Environmental Sustainability: The Prospects for Green Growth; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, M. Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H. A Study of Institutions that Coordinate Policy on Cross-Cutting Issues. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci. 1988, 21, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Weible, C.M. The advocacy coalition framework: Innovations and clarifications. In Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, R.; Peterse, A. Handling frozen fire. Polit. Cult. Risk 1993, 2, 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C. The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In Theories of the Policy Process; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999; pp. 117–166. [Google Scholar]

- Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A. Coalitions, science, and belief change: Comparing adversarial and collaborative policy subsystems. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H. Green Growth and Sustainable Development: Assessing the Sustainability of Korea’s Green Growth Strategies; Korea Economic Institute Research Report; Korea Economic Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J. The harmonization of sustainable development: Law and green growth law in Korea. Sogang Law Rev. 2009, 11, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.-J. The ideological basis and the reality of “low carbon green growth”. ECO 2009, 13, 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. The state-market-society relationship under the Lee Myung-bak government: A study of the low-carbon green growth policy. J. Legis. Stud. 2010, 16, 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, K. “Low carbon green growth” revisited: Critical assessment and prospect. Korean Policy Stud. Rev. 2012, 21, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J. The Politics of the Earth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson, D. Strategy and ideology in environmentalism: A decentered approach to sustainability. Ind. Environ. Crisis Q. 1994, 8, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerman, W. Sustainable development: Is it a useful concept? Environ. Values 1994, 3, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kim, S.H. Accomplishments and goals of green growth. J. Korean Soc. Agric. Mach. 2013, 18, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R. Q methodology and qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, K.E.; Goldberg, A.P. Weight control self-efficacy types and transitions affect weight-loss outcomes in obese women. Addict. Behav. 1996, 21, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, R.; Barry, J.; McClenaghan, A. Northern visions? Applying Q methodology to understand stakeholder views on the environmental and resource dimensions of sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 624–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, A.M. A Dictionary of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Evans Road Cary, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.E. Theory and philosophy of Q methodology. Korean Soc. Public Adm. 2010, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.E. Q Methodology and Sociology; Keumjung: Busan, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Deep Core Beliefs | Policy Core Beliefs | Secondary Aspects |

|---|---|---|

1. Human nature:

3. Basic criteria of distributive justice: whose welfare counts?Relative weights of self, primary groups, all people, future generations, nonhuman beings, etc. 4. Sociocultural identity: ethnicity, gender, religion, profession | 1. Basic value priorities 2. Identification of groups or other entities whose welfare is of greatest concern 3. Overall seriousness of the problem 4. Basic causes of the problem 5. Proper distribution of authority between government and market 6. Proper distribution of authority among levels of government 7. Priority accorded various policy instruments 8. Ability of society to solve the problem 9. Participation of the public, elected officials, and experts 10. Policy core policy preferences | 1. Seriousness of specific aspects of the problem in specific locales 2. Importance of various causal linkages in different locales and over time 3. Most decisions concerning administrative rules, budgetary allocations, disposition of cases, statutory interpretation, and even statutory revision 4. Information regarding performance of specific programs or institutions |

| Belief System | No. | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Core value | 4 | It is impossible to achieve economic growth and protect the environment at the same time. |

| 13 | At this point in time, Korea should put more emphasis on economic growth than anything else. | |

| 14 | At this point in time, Korea should put priority on solving social problems (polarization of wealth, low fertility, and aging). | |

| 15 | Sustainable development should be a top priority, as it is a means of assuring human survival and prosperity. | |

| 18 | Environmental problems inevitably arise in industrial society, and it is impossible to solve these environmental problems without abolishing industrial society. | |

| 19 | Threats to the environment are a matter of the survival of earth and humanity. | |

| 20 | Environmental problems should be resolved at the same time as social problems because of the greater discriminatory effects of environmental problems on the underprivileged, such as low-income and minority groups. | |

| 22 | We should further our society by seeking cooperation between national and local governments and between corporations and civil society. | |

| Policy Core | 1 | Sustainable development is not only a solution to an environmental problem but also a way to address economic and social issues such as wealth polarization, aging, employment, and welfare. |

| 2 | The Lee Myung-bak government’s green growth policy has depressed Korea’s sustainable development policy. | |

| 3 | Green growth is a substitute for sustainable development. | |

| 6 | Low-carbon green growth is a key strategy for making Korea an advanced country. | |

| 7 | The nuclear industry should not be included in the policy of sustainable development. | |

| 16 | Sustainable development is the best solution to global problems such as fine dust that cannot be resolved by the efforts of a single country. | |

| 23 | The idea of sustainable development is a good one, but it is hard to be a national goal because of its abstractness. | |

| 26 | As the fourth industrial revolution accelerates, environmental problems will be solved naturally. | |

| 29 | Green growth is a strategy for promoting sustainable development. | |

| 33 | Low-carbon green growth policy ought to be abolished. | |

| Secondary Aspect | 5 | Sustainable development should be driven by markets and companies. |

| 8 | Sustainable development policy failed because there was no central agency overseeing it. | |

| 9 | If the sustainable development is to be successfully implemented, securing public support must be a first priority. | |

| 10 | In order to successfully promote sustainable development, government must establish a systematic way to implement it. | |

| 11 | To successfully implement sustainable development in general, it is necessary to promote corporate sustainability management. | |

| 12 | Civil society should be the main force in implementing sustainable development, with the help of governments and corporations. | |

| 17 | Sustainable development should be promoted by experts and bureaucrats first, and citizens’ support should be sought later. | |

| 21 | A system based on participatory democracy rather than on the existing bureaucracy is needed to successfully promote sustainable development. | |

| 24 | Sustainable development policies are difficult to adjust because they are too broad. | |

| 25 | Local governments have a weak will when it comes to promoting sustainable development. | |

| 27 | The central government has a weak will when it comes to promoting sustainable development. | |

| 28 | Maintaining both the current Committee on Green Growth and Council on Sustainable Development is a waste. | |

| 30 | It is imperative that the Act on Sustainable Development restore the status of the basic law. | |

| 31 | The Council on Sustainable Development should belong to the prime minister’s office. | |

| 32 | The Committee on Green Growth that is currently belong to the prime minister’s office ought to absorb the Council on Sustainable Development of the Ministry of Environment. | |

| 34 | The president should pay more attention to implementation of sustainable development. | |

| 35 | The successful implementation of sustainable development requires broad participation by stakeholders. | |

| 36 | Human and financial resources are required to enforce compliance with sustainable development legislation. | |

| 37 | Improving ways to evaluate sustainability performance and to provide feedback is critical to successfully promoting sustainable development. |

| General Category | Specific Category | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Expert | Member of UN advisory body, researcher | 5 |

| Bureaucrat | Central and local government officials | 6 |

| Legislature | Ruling party and opposition party | 3 |

| Civic Group | Members of civil society organizations involved in sustainable development | 5 |

| Company | Venture, SME, public corporation, large company representative | 4 |

| Journalist | Newspaper reporter | 1 |

| Total | 24 | |

| Q Sort | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 | Type 5 | P Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3759 | −0.094 | 0.3504 | 0.3559 | 0.0803 | firm |

| 2 | 0.6510 * | 0.3612 | 0.3677 | 0.2091 | 0.0077 | firm |

| 3 | 0.0005 | −0.3329 | 0.0423 | 0.575 | 0.4727 | firm |

| 4 | 0.6055 * | 0.3895 | 0.0768 | 0.182 | −0.3564 | civic groups |

| 5 | 0.6325 * | 0.5957 | −0.1106 | 0.0227 | −0.1726 | bureaucrat |

| 6 | 0.8522 * | 0.1998 | 0.019 | 0.1348 | 0.0575 | researcher |

| 7 | 0.8665 * | 0.0079 | 0.1076 | 0.0917 | 0.0995 | researcher |

| 8 | 0.5195 | 0.4891 | 0.4103 | 0.1065 | 0.1551 | researcher |

| 9 | 0.5221 | −0.0031 | 0.449 | 0.3283 | −0.0104 | legislature |

| 10 | −0.0492 | 0.2827 | −0.0202 | 0.8446 * | 0.024 | legislature |

| 11 | 0.0379 | 0.1525 | 0.1676 | 0.1168 | 0.8774 * | legislature |

| 12 | 0.5788 | 0.3182 | −0.1027 | 0.3944 | 0.439 | bureaucrat |

| 13 | 0.0724 | 0.2877 | 0.8029 * | 0.2608 | −0.1437 | bureaucrat |

| 14 | 0.7406 * | 0.262 | 0.0554 | 0.2703 | −0.09 | civic groups |

| 15 | 0.7431 * | 0.2686 | −0.0329 | 0.0764 | 0.1233 | firm |

| 16 | 0.7689 * | 0.1428 | −0.0527 | −0.1534 | −0.1026 | researcher |

| 17 | −0.1493 | −0.082 | 0.7808 * | −0.1167 | 0.3512 | journalist |

| 18 | 0.3525 | 0.2097 | 0.3316 | 0.5952 * | 0.1066 | bureaucrat |

| 19 | 0.6320 * | 0.1116 | 0.5321 | −0.0838 | 0.1199 | bureaucrat |

| 20 | 0.2126 | 0.7467 * | 0.1126 | 0.2622 | 0.2837 | civic groups |

| 21 | 0.7843 * | 0.1393 | 0.2106 | 0.385 | −0.1083 | bureaucrat |

| 22 | 0.8522 * | 0.1653 | 0.111 | −0.0731 | 0.0749 | civic groups |

| 23 | 0.6866 * | 0.1929 | 0.2678 | 0.2725 | 0.288 | UN advisory |

| 24 | 0.5522 | 0.6546 * | 0.18 | 0.0225 | −0.0333 | civic groups |

| Explanatory Power (%) | 34 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 73 |

| Correlation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 0.6054 | 0.1541 | 0.2526 | 0.1217 |

| 2 | - | 0.2378 | 0.3660 | 0.2667 | |

| 3 | - | 0.2294 | 0.2340 | ||

| 4 | - | 0.2397 |

| Value * | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 34 | The president should pay more attention to implementation of sustainable development. |

| 4 | 2 | The Lee Myung-bak government’s green growth policy has depressed Korea’s sustainable development policy. |

| 4 | 19 | Threats to the environment are a matter of the survival of earth and humanity. |

| 3 | 22 | We should further our society by seeking cooperation between national and local governments and between corporations and civil society. |

| 3 | 30 | It is imperative that the Sustainable Development Act restore the status of the basic law. |

| 3 | 20 | Environmental problems should be resolved at the same time as social problems because of the greater discriminatory effects of environmental problems on the underprivileged, such as low-income and minority groups. |

| −3 | 13 | At this point in time, Korea should put more emphasis on economic growth than anything else. |

| −3 | 17 | Sustainable development should be promoted by experts and bureaucrats first, and citizens’ support should be sought later. |

| −3 | 23 | The idea of sustainable development is a good one, but it is hard to be a national goal because of its abstractness. |

| −4 | 4 | It is impossible to achieve economic growth and protect the environment at the same time. |

| −4 | 3 | Green growth is a substitute for sustainable development. |

| −5 | 32 | The Committee on Green Growth that currently belongs to the prime minister’s office ought to absorb the Council on Sustainable Development of the Ministry of Environment. |

| Value * | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 16 | Sustainable development is the best solution to global problems such as fine dust that cannot be resolved by the efforts of a single country. |

| 4 | 19 | Threats to the environment are a matter of the survival of earth and humanity. |

| 4 | 22 | We should further our society by seeking cooperation between national and local governments and between corporations and civil society. |

| 3 | 15 | Sustainable development should be a top priority, as it is a means of assuring human survival and prosperity. |

| 3 | 21 | A system based on participatory democracy rather than on the existing bureaucracy is needed to successfully promote sustainable development. |

| 3 | 20 | Environmental problems should be resolved at the same time as social problems because of the greater discriminatory effects of environmental problems on the underprivileged, such as low-income and minority groups. |

| −3 | 8 | Sustainable development policy failed because there was no central agency overseeing it. |

| −3 | 27 | The central government has a weak will when it comes to promoting sustainable development. |

| −3 | 26 | As the fourth industrial revolution accelerates, environmental problems will be solved naturally. |

| −4 | 32 | The Committee on Green Growth that currently belongs to the prime minister’s office ought to absorb the Council on Sustainable Development of the Ministry of Environment. |

| −4 | 33 | Low-carbon green growth policy ought to be abolished. |

| −5 | 29 | Green growth is a strategy for promoting sustainable development. |

| Value * | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 22 | We should further our society by seeking cooperation between national and local governments and between corporations and civil society. |

| 4 | 29 | Green growth is a strategy for promoting sustainable development. |

| 4 | 12 | Civil society should be the main force in implementing sustainable development, with the help of governments and corporations. |

| 3 | 31 | The Council on Sustainable Development should belong to the prime minister’s office. |

| 3 | 1 | Sustainable development is not only a solution to an environmental problem but also a way to address economic and social issues such as wealth polarization, aging, employment, and welfare. |

| 3 | 34 | The president should pay more attention to implementation of sustainable development. |

| −3 | 26 | As the fourth industrial revolution accelerates, environmental problems will be solved naturally. |

| −3 | 18 | Environmental problems inevitably arise in industrial society, and it is impossible to solve these environmental problems without abolishing industrial society. |

| −3 | 7 | The nuclear industry should not be included in the policy of sustainable development. |

| −4 | 28 | Maintaining both the current Committee on Green Growth and Council on Sustainable Development is a waste. |

| −4 | 33 | Low-carbon green growth policy ought to be abolished. |

| −5 | 2 | The Lee Myung-bak government’s green growth policy has depressed Korea’s sustainable development policy. |

| Value * | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 23 | The idea of sustainable development is a good one, but it is hard to be a national goal because of its abstractness. |

| 4 | 28 | Maintaining both the current Committee on Green Growth and Council on Sustainable Development is a waste. |

| 4 | 37 | Improving ways to evaluate sustainability performance and to provide feedback is critical to successfully promoting sustainable development |

| 3 | 22 | We should further our society by seeking cooperation between national and local governments and between corporations and civil society. |

| 3 | 23 | The idea of sustainable development is a good one, but it is hard to be a national goal because of its abstractness. |

| 3 | 24 | Sustainable development policies are difficult to adjust because they are too broad. |

| −3 | 34 | The president should pay more attention to implementation of sustainable development. |

| −3 | 30 | It is imperative that the Sustainable Development Act restore the status of the basic law |

| −3 | 31 | The Council on Sustainable Development should belong to the prime minister’s office. |

| −4 | 10 | In order to successfully promote sustainable development, government must establish a systematic way to implement it. |

| −4 | 12 | Civil society should be the main force in implementing sustainable development, with the help of governments and corporations. |

| −5 | 26 | As the fourth industrial revolution accelerates, environmental problems will be solved naturally. |

| Value * | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 19 | Threats to the environment are a matter of survival of the earth and humanity. |

| 4 | 17 | Sustainable development should be promoted by experts and bureaucrats first, and citizens’ support should be sought later. |

| 4 | 18 | Environmental problems inevitably arise in industrial society, and it is impossible to solve these environmental problems without abolishing industrial society. |

| 3 | 11 | To successfully implement sustainable development in general, it is necessary to promote corporate sustainability management. |

| 3 | 36 | Human and financial resources are required to enforce compliance with sustainable development legislation. |

| 3 | 37 | Improving ways to evaluate sustainability performance and to provide feedback is critical to successfully promoting sustainable development. |

| −3 | 32 | The Committee on Green Growth that currently belongs to the prime minister’s office ought to absorb the Council on Sustainable Development of the Ministry of Environment. |

| −3 | 21 | A system based on participatory democracy rather than on the existing bureaucracy is needed to successfully promote sustainable development. |

| −3 | 25 | Local governments have a weak will when it comes to promoting sustainable development. |

| −4 | 7 | The nuclear industry should not be included in the policy of sustainable development. |

| −4 | 12 | Civil society should be the main force in implementing sustainable development, with the help of governments and corporations. |

| −5 | 2 | The Lee Myung-bak government’s green growth policy has depressed Korea’s sustainable development policy. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, H.; Eun, J. Exploring Perceptions of Sustainable Development in South Korea: An Approach Based on Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Belief System. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040054

Lim H, Eun J. Exploring Perceptions of Sustainable Development in South Korea: An Approach Based on Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Belief System. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2018; 4(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Hyunjung, and Jonghwan Eun. 2018. "Exploring Perceptions of Sustainable Development in South Korea: An Approach Based on Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Belief System" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 4, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040054

APA StyleLim, H., & Eun, J. (2018). Exploring Perceptions of Sustainable Development in South Korea: An Approach Based on Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Belief System. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040054