2. Hallyu Beginnings

As mentioned earlier, Japan, along with China [Hong Kong] and India, were leading forces when it came to popular culture products, mainly TV drama and movies. Koichi Iwabuchi, however, referred only to Japan [

7] (p. 2). According to Euny Hong, Asian drama and music clearly lost out to Korean drama and Korean music [

8] (p. 200). The birth of the

Korean Wave in Asia and, later, the world was coincidental, yet this does not mean that it came out of a vacuum. In an interview Hong, Lee Moon-Won, a renowned Korean cultural critic, states that the surge of

Hallyu in Asia and beyond was born in Korea out of “necessity” after the financial crisis hit Asian markets in 1997 [

8] (p. 91). When the major sectors of the Korean economy were hit by financial burdens, Koreans were forced, according to Iwabuchi and others, to try other venues; one of these was cultural products [

9] (p. 2). In what Doobo Shim [

10] labels the “

Jurassic Park factor,” Koreans started to take a different route. Shim summarizes this as follows:

In 1994, the Presidential Advisory Board on science and technology proposed to President Kim Young-Sam that Korea should develop cinema and other media content production as a national strategy industry. What the proposal highlighted was the fact that the total revenue of the Hollywood movie Jurassic Park matched the total revenue of the foreign sales of 1.5 million Hyundai cars …

This suggestion was taken seriously. What the Korean government learned from this was that diversification of revenue sources would combat potential future financial collapses. In 1996, Korea exported

$2.25 billion worth of mobile phone equipment from the USA and

$3.4 billion in 2000, which rocketed to

$20.2 billion in 2012 [

4] (p. 158). As indicated by the comparative graph study provided by Hyejung Ju, revenue from Korean TV was less than 8 billion in 1998 but this increased to 132 billion in 2001 and rocketed to 172 billion in 2010 [

11] (p. 35).

The first K-drama,

What Is Love (사랑이 뭐길래), was aired by the Chinese network

CCTV in January 1997 and it was the Chinese press that coined the nickname “The Korean Wave” or

Hallyu [

12] (p. 20), [

13] (p. 1). The watershed came in 2003 when

Winter Sonata was broadcast in Japan and achieved unprecedentedly high viewership and ratings, especially among young, middle-aged and older female viewers. The success of Korean drama in other parts of Asia is evidenced, according to Huat and Iwabuchi [

14] (p. 7), by the fact that they are now part of the “daily programming of many local television stations in both afternoon and evening schedules.” The other TV dramas that appealed to the people in the Middle East include, but are not limited to,

Boys Over Flowers,

Jewel in the Palace,

Sorry I Love You, and

Woman of the Sun [

6]. Most recently,

Descendants of the Sun (2016) and

Goblin (2017) have also been well received by millions of viewers worldwide. However, upon the declaration that South Korea would deploy a THAD system to protect its cities from potential North Korean attacks, China started to crack down on Korean culture and products in China [

15,

16].

Literary critics and historians categorize the history of

Hallyu in many different ways. Some group

Hallyu into either

Hallyu or

Neo-Hallyu, while others classify it into four different phases:

Hallyu 1.0,

Hallyu 2.0,

Hallyu 3.0, and

Hallyu 4.0. Historically and generically, in this regard, Yong Dal Jin classifies the

Korean Wave into two phases: what he labels “Hallyu 1.0” and “Hallyu 2.0” [

4] (p. 4). According to Jin, the first phase spanned from the 1990s to 2007, and the second phase from 2007 to the present [

4] (pp. 4–5). What is characteristic about the second

Hallyu wave is that it included other types of cultural products, such as digital and online gaming products and even cosmetics and plastic surgery. With the technological surge in the smartphone industry, as early as 2007, and prevailing social media networks such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, etc., millions of fans all over the world managed to view Korean cultural technology and products, and this came to be known as

Hallyu or the

Korean Wave. Now we are in the era of

Neo-Hallyu. Recently, new dimensions have been added and

Neo-Hallyu may include K-culture, K-products, K-beauty, etc. Thus, Korean cars, mobile phones, fashion, food and plastic surgery are all segments of

Neo-Hallyu.

Why have K-drama and K-pop succeeded in so many parts of the world so far? The following reasons can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

Cinematography;

- (2)

Governmental factors;

- (3)

The role played by social media websites (Jin refers to the role played by social media networks on Hallyu, especially during the second phase [

4] (p. 5). It is clear that social media has played a significant role in the spread of the Hallyu, and of course other similar cultural and media stuff. The Korean Wave is not limited to TV dramas, films, K-pop, animations, and video games. It even includes smartphone applications (such as Kakako Talk, Otto and Line, etc.) plastic surgery, cosmetics or fashion.);

- (4)

Harmony in music [

17] (p. 55), [

8] (p. 130) (Chuyun Ho and Euny Hong noticed that dancing styles and etiquettes might also play a role. Unlike many other performing bands, boy and girl bands play an important role in the production of K-pop music shows [

17] (p. 55); [

8] (p. 130]);

- (5)

Less/lack of nudity or violence. The majority of scholars and commentators who have discussed Hallyu are of the mind that Korean TV dramas have been classified as “safe” to watch by the generally conservative Arab‒Muslim viewers; and

- (6)

Family matters and cultural and religious sensitivities.

Concerning the factors behind the success of

Hallyu, Iwabuchi argues that Korean dramas touch on topics that deal with the problems, needs, or inner feelings of people of all ages rather than concentrating on youth and its problems, as in Japanese drama [

18] (p. 264). Quoting from

Hallyu Forever (a book published by the Korean Cultural Trade Commission, available only in Korean), Hong refers to the fact that Koreans producers keep in mind Arab customs and religious backgrounds when airing K-drama in the Arab world. Hong refers to one of the chapters in the book and points out “the importance of keeping Muslim prayer times in mind” (to avoid airing Korean TV programs during these times), as well as detailing the strict sexual/moral code that would make certain Korean dramas a bad fit for the Arab market [

8] (pp. 195–196). In the same vein, referring to the fact that American drama and music are losing ground to other global vendors (such as Korea and Turkey), Seung Bak (a Korean American, and founder of a website that airs K-drama) tells Hong that:

Unlike shows from some other countries … whereas characters have sex in the first two minutes, a Korean drama can get to episode eight before the couple has even a slight kiss. The drama focuses a lot on story and courtship, and women all over the world especially want that. [That is why, for example,] In Iran, women schedule their dinners so they don’t interfere with Korean shows.”

However, on some rare occasions, Korean K-pop or K-drama violated the seemingly good relations between Korea and the Arab and Muslim world. The earliest incident happened in 2011, when a contender on a reality TV show entitled

Star King posed as an Arab man and, armed with a gun, started to attack the TV presenter in a mocking parody. The show was stopped within minutes and

SBS network and the Korean government apologised. The second episode happened between 2014 and 2016 when K-Pop star CL (born Lee Chaelin) used a backing track in one of her songs in which verses from the Quran were heard in the background (Chapter 78, verses 32–33). CL and her sponsor, YG Entertainment, issued an apology on her Twitter account (for Arabic sources see:

https://al-ain.com/article/korean-singer-apologizes-for-the-second-time-on-the-use-of-the-koran and for sources in English see: Tamar Herman

https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/k-town/7565888/cl-apology-quran-tour; and Jennywill

https://www.allkpop.com/article/2016/11/cl-goes-under-fire-for-once-again-using-the-quran-verse-in-her-mtbd-performance; sites visited on 4 September 2018). The third and last incident (I am not aware of any others) is from 2017 in the TV drama

Man Who Dies to Live, starring Chio Min-Soo, who plays the role of a wealthy Arab tycoon, Saeed Fahid Ali. There are a few themes in the series that many Muslims took to be very offensive to Islamic culture. Very early in the series, we see girls donning hijab and bikinis at the same time and some others drinking alcohol. To be fair, consuming alcohol is seen as a dreadful act only by the Methodists and ultra-religious fans who hardly watch dramas or movies. However, what appalled the audience is that in one of the scenes the hero is seen sitting cross-legged on an armchair with his feet facing and very close to the

Holy Quran, an act that the majority of Muslims will deem very offensive (see, for example, “المسلسل المثير للجدل "رجل يموت ليعيش" يتصدر مؤشر الشعبية,” [Controversial TV Drama tops popularity index],

http://arabic.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2017/08/01/0200000000AAR20170801001400885.html, Jon Maala “Drama ‘Man Who Dies to Live’ tops popularity index despite backlash,”

http://www.ibtimes.sg/drama-man-who-dies-live-tops-popularity-index-despite-backlash-13388 and Yoon Min-sik, “Man Who Dies to Live’ apologizes for its depiction of Islamic culture,”

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170723000242, cites visited on 04/09/2018). See also

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Hallyu Success and Korean Brands

For many decades now, Korean governments have been working hard, as has been noted earlier, to diversify the Korean economy. During the financial crisis of 1997, when some Asian economies collapsed and never came back, Koreans realized that they must no longer depend only on

chaebols (Korean family-owned companies such as Samsung, LG or Hyundai with a lot of market share). According to the data provided by Jin [

4], the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism showed that the total income from export of cultural products (including K-drama, K-pop, etc.) was only US

$188.9 million in 1998 but rocketed to

$4042.3 billion in 2014 [

4] (p. 25). I think that the main reason behind the unique surge of Korean products, including

Hallyu, is the developing democracy in Korea. To substantiate my point of view, Korea’s economic GDP, before introducing democracy to Korea in 1987, was lower than that of North Korea, or even Ghana [

8] (p. 2). In 1997, Korea had to apply for a loan from the IMF. The IMF stipulated that Korea should open its doors to the outside world and it has done so with amazing results. Korea has moved from a Third World country to a First World country within a short space of time. Korean products, cultures, food, fashion, etc. have become known all over the world. Had South Korea kept its doors closed and not agreed to the conditions of the IMF in 1997, it could have been in economic strife similar to North Korea.

In what Hong considered one of the greatest “economic miracles of the modern day,” the Korean economy jumped from near the bottom of world economies to the top 20 economies in the world. I would agree, in this context, with Hong, who argues that it would not be “an exaggeration to say that

Hallyu is the world’s biggest, fastest cultural paradigm shift in modern history” [

8] (p. 4). Kim argues that

Hallyu is a driving force in the era of creative cultural economy: an economy not only concentrated on producing goods but on cultural economy products. Kim adds that one of the most important key targets Park Geun-hye (the 11th Korean president) had set was treating

Hallyu as a part of a larger creative economy [

2]. Hong, in a similar vein, states that the cultural economy was one of the priorities of President Park since she was elected in 2013.

Hallyu, as a commodity, helps promote other Korean goods such as cars, electronics and digital products (such as mobile phones and computers), and tourism, especially medical tourism. The data provided by Charm Lee [

19] indicate that this has been going well. In this regard, Lee states that the economic value of the

Hallyu was

$6.4 billion in 2012,

$18.1 billion in 2015 and

$52.1 billion in 2020. Koreans, like anybody else, do not spend billions of dollars on

Hallyu for the sake of it. In other words, the success of

Hallyu is the best advertisement for Korean products, such as cars, mobile phones, digital or home appliances, and even hospitals and infrastructure. The audience observe TV stars wearing Korean brands, using Korean phone mobile phones, and driving Korean cars. In this regard, it is worth reiterating that Korean sponsoring companies require Korean actors to use their branded products when shooting scenes [

8] (p. 176).

There is a link between

Hallyu and the success of Korean brands such as Samsung, LG, Hyundai or Kia. Citing an article by Yoon Ja-young in the

Korea Times, Martin Roll [

20] (p. 48) argues that

Hallyu has “a direct impact on encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI) and the tourism industry in Korea” confirming that the “visual content from the Korean Wave is very effective in promoting Korea and consumption of Korean goods.” In the same vein, Jin argues that the “global popularity of Korean smartphones has created two unique phenomena in the world: digital

Hallyu and its link to the Korean Wave” [

4] (p. 159). These giant companies play an important role in the rise or fall of the Korean economy. Koreans utilize the success of

Hallyu to advertise and promote Korean products worldwide. When recording TV dramas or songs, Koreans are keen to use Korean products and locations. In this regard, Chung Taewon tells Hong that “all the characters in

Iris [a TV drama shot in Hungary] had to drive the Kia brand of car, whether the characters were South Koreans, North Koreans, or European. We had to send Kia models K5 and K7 by airplane [sic] to Hungary so that all the actors there could be shown driving it” [

8] (p. 176). Koreans seem to be mindful of the positive correlation between the success of Korean giant firms and their own prosperity and welfare. This has been made clear to me by something one of my students in Korea said in 2016: “if Samsung is sick, Korea is sick”. This materialized in the second half of 2016 when the Samsung Note 7 mobile phone suffered a decline in sales and later was withdrawn from the market due to a fault in the battery. As a result, the U.S. dollar rose dramatically against the Korean won.

3. Neo-Hallyu in the Arab World: Achievements and Challenges

In his book on the

Korean Wave, Jin [

4] did not include any of the Mediterranean or Arabian countries as being among the recipients of

Hallyu. Jin referred to Asia, North America and South America but did not mention any Middle Eastern country. He argues that, while “Asia has been the largest cultural market for the Korean cultural industries, other parts of the world, including North America, western [sic] Europe, and South America, have gradually admitted Korean products popular culture, both audio-visual and digital technologies” [

4] (p. vii).

In this section, I will examine the reception of the

Korean Wave in the Arab world and the Middle East. The data I rely on are collected from the Internet and Arab newspapers (whenever possible), with more emphasis given to social networks such as Facebook and YouTube. The reason for this is that the majority of

Hallyu fans in the Middle East are members of younger generations who mainly use SNS to watch, download and react to

Hallyu. (In an interview with Kim Sun Wan, professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, and Kim Jaehee, a professor teaching Arabic translation at some Korean universities and a

KBS broadcaster who hosted many Hallyu K-pop bands in her programs, both agreed that the majority of Arab

Hallyu fans are young girls.) Hence, Facebook and YouTube will be the main benchmarks against which I weigh the presence and reception of

Hallyu in the Middle East. In spite of the fact that

Hallyu is now well established in Western as well as Eastern countries, I think that Korea does not intend to compete by seeming to invade Western music, drama and movie industries that are already successful and have influence in many parts of the world, including on Korean

Hallyu itself. Rather, I agree with Hong when she argues that “if they [Koreans] being honest with themselves [they would not] believe their music will make up significant market share in the United States or western [sic] Europe. Instead, it’s about getting the crucial but still dormant third-world market hooked on Korean pop culture” [

8] (p. 5). But why does

Hallyu succeed in the Arab world? Kim [

2] (p. 11) argues that cultural factors play an important role in the success of

Hallyu in the Arab world. Among these factors are the social habits and customs that Arabs share with Koreans, such as family bonds, love stories that are not explicit, friendship, altruism, etc. Compared to Western pop music with its nudity and obscene lyrics, K-pop fits well into mainstream Arab societies and the majority of viewers would not see it as offensive, but perhaps more related to notions of sexuality and sensuality in their own culture. Korean drama and pop music have become so popular in the Arab‒Islamic World that Kim nicknamed the region the “blue ocean of the

Korean Wave” [

2] (p. 5). Kim states that Korean companies sold hundreds of hours of TV drama products to Arab and Mediterranean countries, mainly the United Arab Emirates [UAE] and other Gulf TV channels.

Hallyu prospered and penetrated into Asian society effortlessly because many of these Asia countries share Confucian values [

21]. In a way, this is correct, but we should remember that the majority of Asian countries are not Confucian. Again,

Hallyu has been successful in Confucian, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian and Muslim countries alike. K-drama penetrated into the Arab world as early as the late 1980s, and K-pop reached the region more than 10 years later. The K-pop song “Gangnam Style,” issued by Psy in 2012, popularised via YouTube, introduced many Arab fans to the world of K-pop. K-pop received millions of hits in the Arab world, with Saudi Arabia [KSA] scoring 42.17 million hits by 2013, the UAE 4.8 million and Kuwait 1.7 million [

2] (p. 10). If K-drama has its fans in the Middle East and Arab world, K-pop is no less famous in the region. The most important singers who have received attention among Arab audiences include, but are not restricted to, Park Shin-hye, Jung Yong Hwa, Leetueke and Lee-min, while the most famous groups include Girl Generation, Super Junior, SM Entertainment and SHINee.

Regarding the relationship between Korea and the Middle East, Hee Soo Lee dates Korean‒Arab and Korean‒Islamic relations back to the medieval period. Lee states that “relations between Korea and the Islamic world can be traced back to the middle of the ninth century, when Ibn Khurdadhbih mentioned the ancient Silla Kingdom in his

Kitab al-Masalik wa-l-Mamalik” [

22]. Hee adds that Korea had trade relations with the Middle East even before the appearance of Islam:

Long before the advent of Islam, Korea and the Middle East had already established trade relations by sea and overland routes such as the Silk Road. Written references are few and far between, but there is sufficient documentation to demonstrate the existence of significant commercial ties. One example is the discovery of Roman and Persian glass cups in the ancient tombs of Gyeongju, capital of the Silla kingdom.

Here I agree with Alon Levkowitz, who argues that Korean‒Middle East relations have been “neglected in the [academic] literature throughout the years [….] Until the 1960s, Seoul’s policy toward the Middle East could be defined as passive, if not unimportant, owing to Korea’s lack of interest in the Middle East” [

23] (p. 1). Studies on the Korean‒Middle Eastern relationship are rare (at least in English) and this, continues Levkowitz, deserves greater attention nowadays [

24] (p. 7). It is not implausible to argue that Korean

Hallyu started in the Middle East in the 1960s‒70s, when South Korean companies moved their business interests to Middle Eastern countries, especially the Gulf area. Companies such as Samsung, Hyundai and Daewoo won tenders to undertake major construction contracts in Arab countries [

23,

25]. In this regard, Nigel Disney [

26] (p. 22) argues that in the 1970s Korea had more than 20,000 workers in the Middle East. Korean labour was very cheap compared to other nationalities and Korean workers were known for being hard-working and obedient. Disney states that Korean companies earned only

$11 million in 1966, but this rocketed to

$4.2 in the 1970s [

26] (p. 23). When it came to Korean exports to the Middle East, Disney argues that Korea had exported

$45 million worth of products to the Middle East in 1973 and this rose to

$900 million in 1976, with Saudi Arabia being the main partner. To boost its economy, Korea borrowed

$24 million from Kuwait in 1976 and in 1977 the first joint Korean‒Arab bank was opened in Seoul [

26] (p. 23). In the span of four decades, Korean companies have implemented projects or exported goods worth hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars. In 2012 alone, Korea’s bilateral trade with Saudi Arabia amounted to

$48.8 billion [

24] (p. 8).

Hence, one can say that these humble workers laid the foundation for what was to later to be known as powerful industrial South Korea, with its mega construction, automotive, digital and electronic products. Korean products entered the Middle East as early as the 1960s but only yielded a significant profit in the 1990s. As far as I can recall, the first Korean product I ever had was a T-shirt (very similar to the one worn by bus drivers in Korea nowadays) I bought from the free zone in the coastal city port of Port Said in Egypt in 1986 or 1987. Since the 1990s, there has been a steady increase in the number of Korean cars appearing in the streets of Arab countries.

Tuk [

27] (p. 17) argues that

Daejanggeum [대장금/Dae Jang-geum] and

Winter Sonata [겨울연가/Gyeoul Yeonga] achieved considerable success in many countries, including in the Middle East. According to Tuk, the list of counties where

Daejanggeum was a hit included Japan, China, Taiwan, India and Malaysia. “The drama [not] only got Asian fans, but also fans in Russian, Turkey, Iran and Israel.” Tuk did not mention any Arab country!

Daejanggeum got a viewer rating of 57% on its debut in Iran in 2006. This led to the import of more Korean dramas. The dramas inspired Iranians to learn Korean, according to the Korean Culture and Information Service.

Jumong [삼한지-주몽 편/Samhanji-Jumong Pyeon] is another Korean drama that Iranians liked; the series got an 85% viewership rating when it was broadcast in Iran in 2008. “The actors of this show [sic] appear in different advertisements in Iran” [

27] (p. 17).

When it comes to the presence of the

Korean Wave in the Arab world, one can say that K-drama found its way into the Arab world in the 2000s with the popularity of social media outlets that helped boost

Hallyu not only in the Arab world but all over the world. Kim argues that “

Little Kid-Jkokkomi” was the first Korean visual media product to have been broadcast in the Arab world, in Jordan in 1998. Later, the first Korean TV drama,

The Youth, aired in Jordan in 2002, followed by

The 1st Coffee Prince and

Winter Sonata in 2007, on Jordan TV as well [

2] (p. 5)

Winter Sonata was a great hit in the Arab world and beyond. Other K-dramas that appealed to viewers in the Arab and Islamic world, include, among many others,

Winter Sonata,

Jumong and

Jangeum and had a viewership rating of over 90% in Iran [

2] (p. 7).

5. Findings

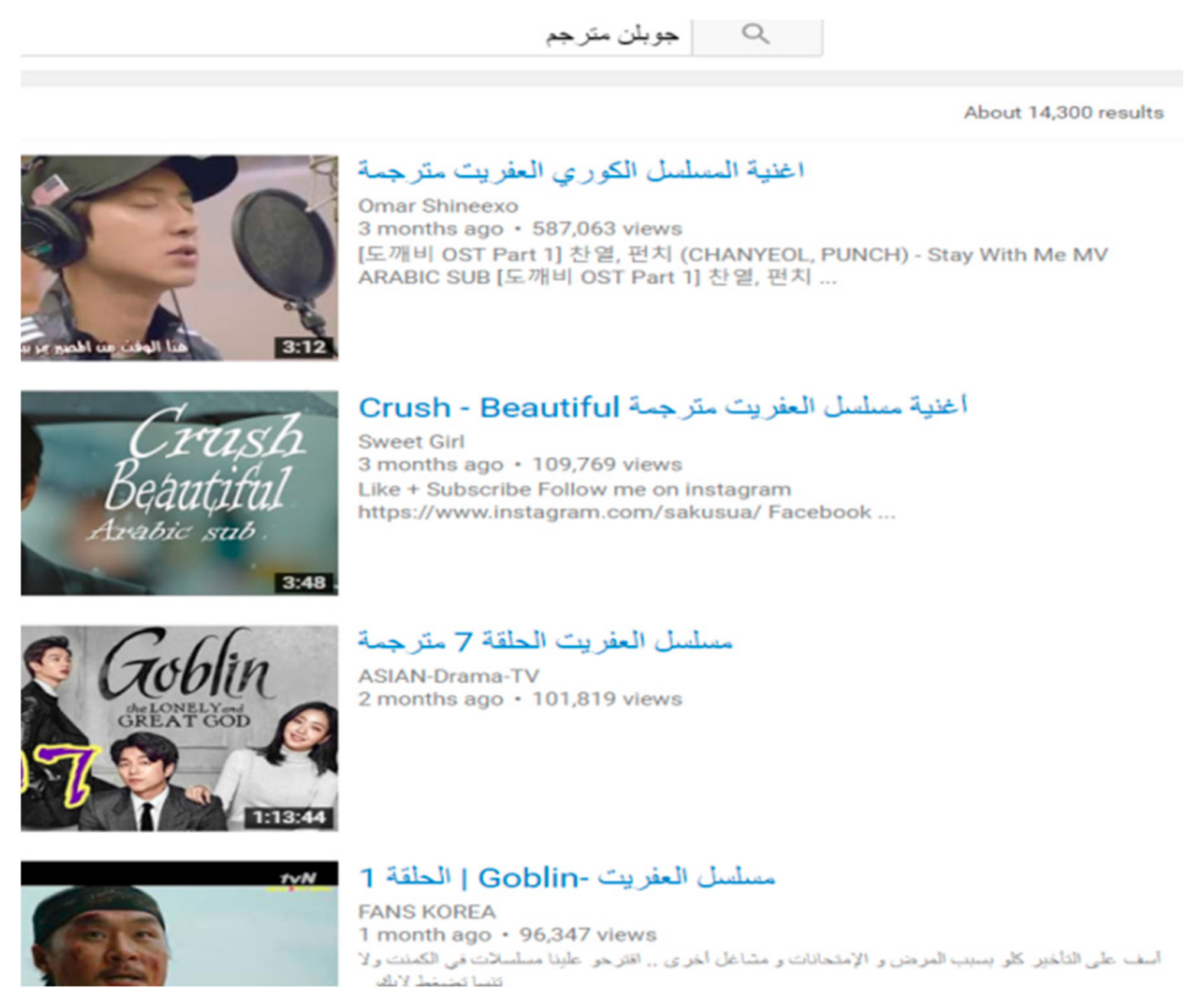

Regarding the reception of

Hallyu in the Middle East/Arab world, I conducted a search on Facebook on 19 June 2016 and found that

Hallyu has a huge number of fans in the Arab world. Starting with Lee Min-ho, I found at least 98 fan pages in Arabic and 27 Arab fan pages in English. The volume of Lee Min-ho’s fans in the Arab world is incredible. Surveying Lee Min-ho’s and Park Shin-hye’s Arab fan pages, Shin-hye came out on top with some of her Arab fan pages in English numbering (as of 19 June 2016) 553,823, 9283, 8428 and 2227 fans, while her Arab fan pages in Arabic have slightly fewer, with 4452, 2242 and 1521. Min-ho, on the other hand, came second after Shin-hye. Min-ho’s Arab fan pages in English had (as of 19 June 2016) 71,187, 35,542, 18,952, 16,980, 8563, and 7239 likes, while his fan pages in Arabic got 5560, 3432, 3357 and 3212 likes. This does not include other fan pages dedicated, for example, to K-drama,

Hallyu, or even TV dramas (such as

Winter Sonata,

Descendants of the Sun, etc.) in which these stars appeared (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

From the many surveys I have undertaken on the Internet and SNS websites between 2015 and 2016, I can say that there are hundreds of

Hallyu fan pages on SNS websites. For example, there are at least nine major fan pages in Arabic for Park Shin-hye on Facebook. In addition, there are some pages by Arab fans in English as well. In this regard, “The Park Shin-hye Arab Fans Club” Facebook page had 480,534 members in January 2016. It seems that Shin-hye has more fans in the Arab world than in her native South Korea. What is strange about

Hallyu is that K-pop stars seem to have more fans outside Korea. Lee Min-ho, Park Shin-hye and Leeteuk are among the most famous Korean celebrities in the Arab world. In a poll for Arab listeners conducted by

KBS Arabic radio in 2015, Lee Min-ho and Park Shin-hye fared very well. Min-ho and Shin-hye seem to be so popular in the Arab world that Lee Min-ho came top in a poll of 3000 radio listeners in 22 Arabic-speaking countries conducted by terrestrial broadcaster

KBS in 3–17 September 2015, while Park Shin-hye “got 5.1 percent of the votes and Park Geun-hye tied for fifth place with 2.6 percent” [

31].

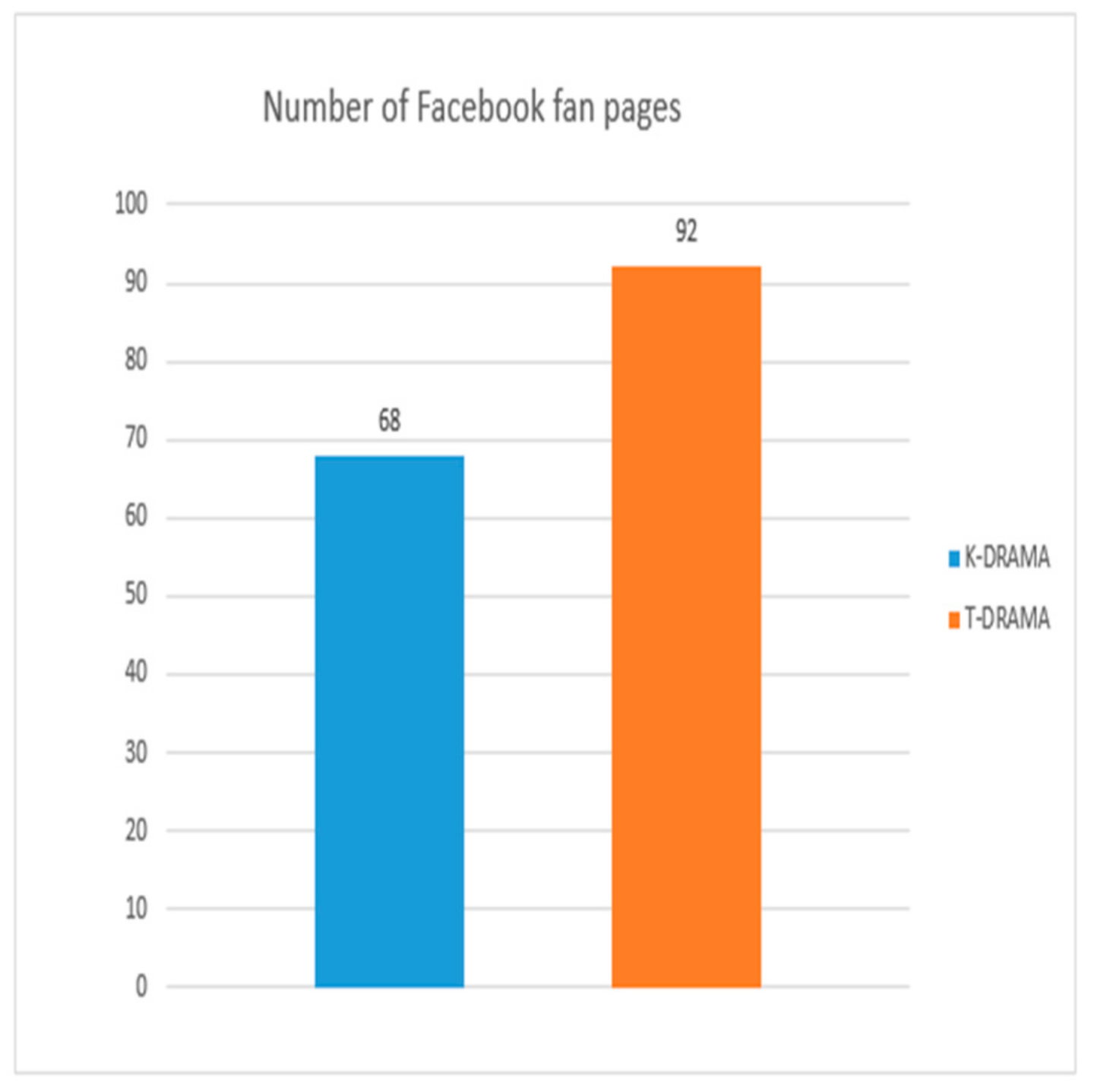

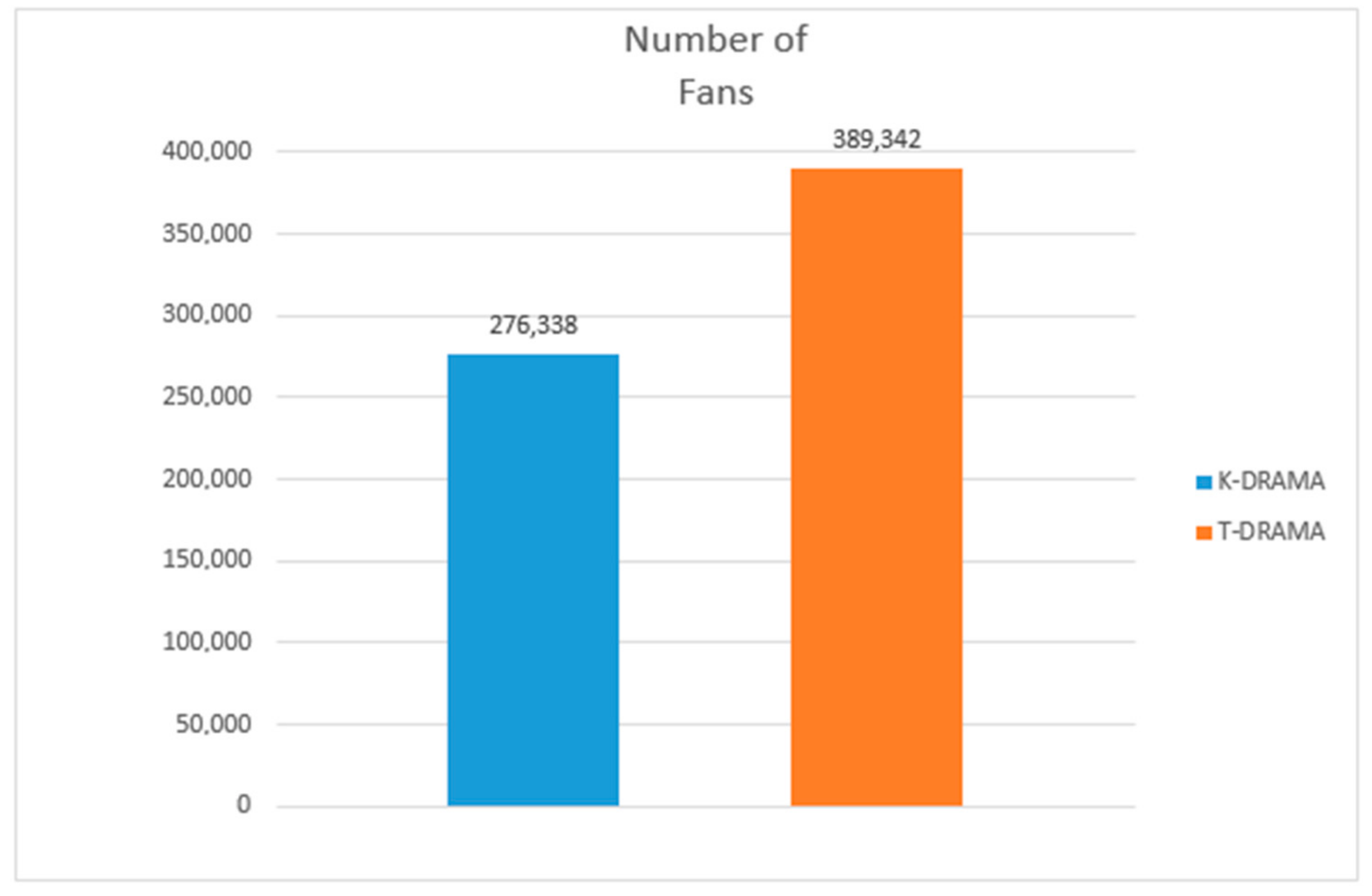

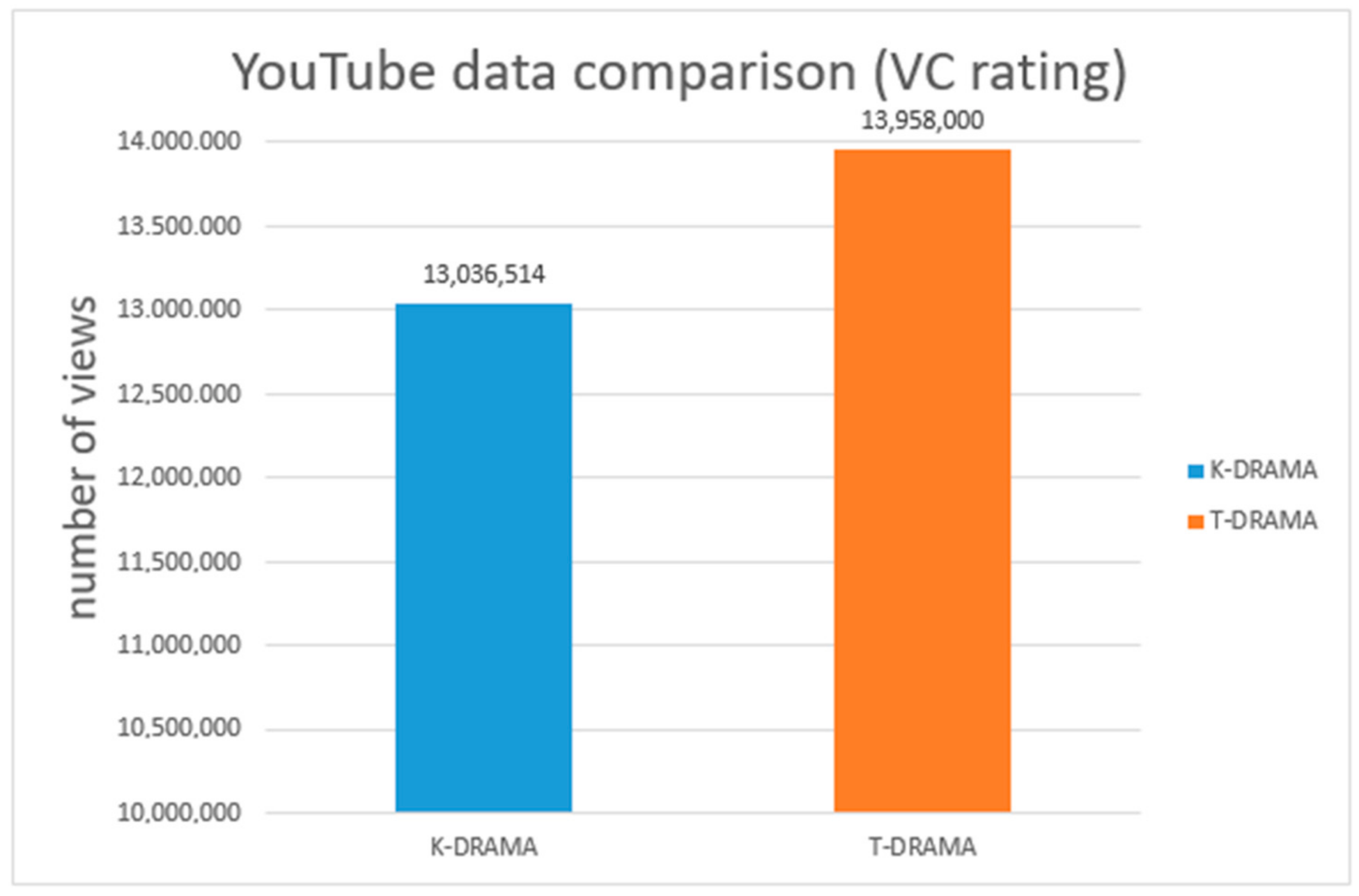

A search on the reception of Korean and Turkish drama on Facebook and YouTube in December 2016 was undertaken. First, a search on Facebook in November–December 2016 (using the same keywords and same procedures for analysing the data) had the following results (search entry “Korean drama” and “Turkish drama”, method used: view-count factor), see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6):

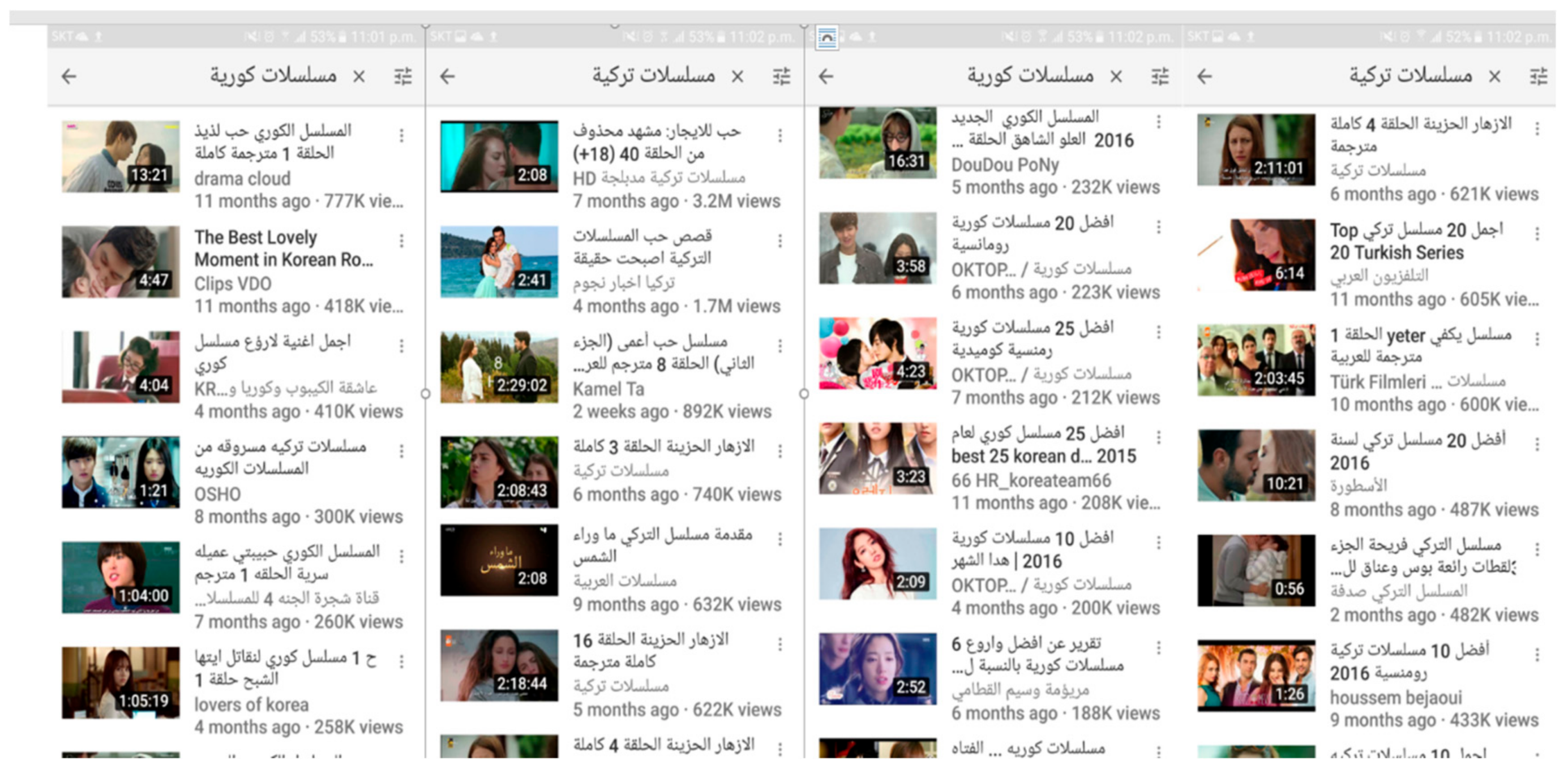

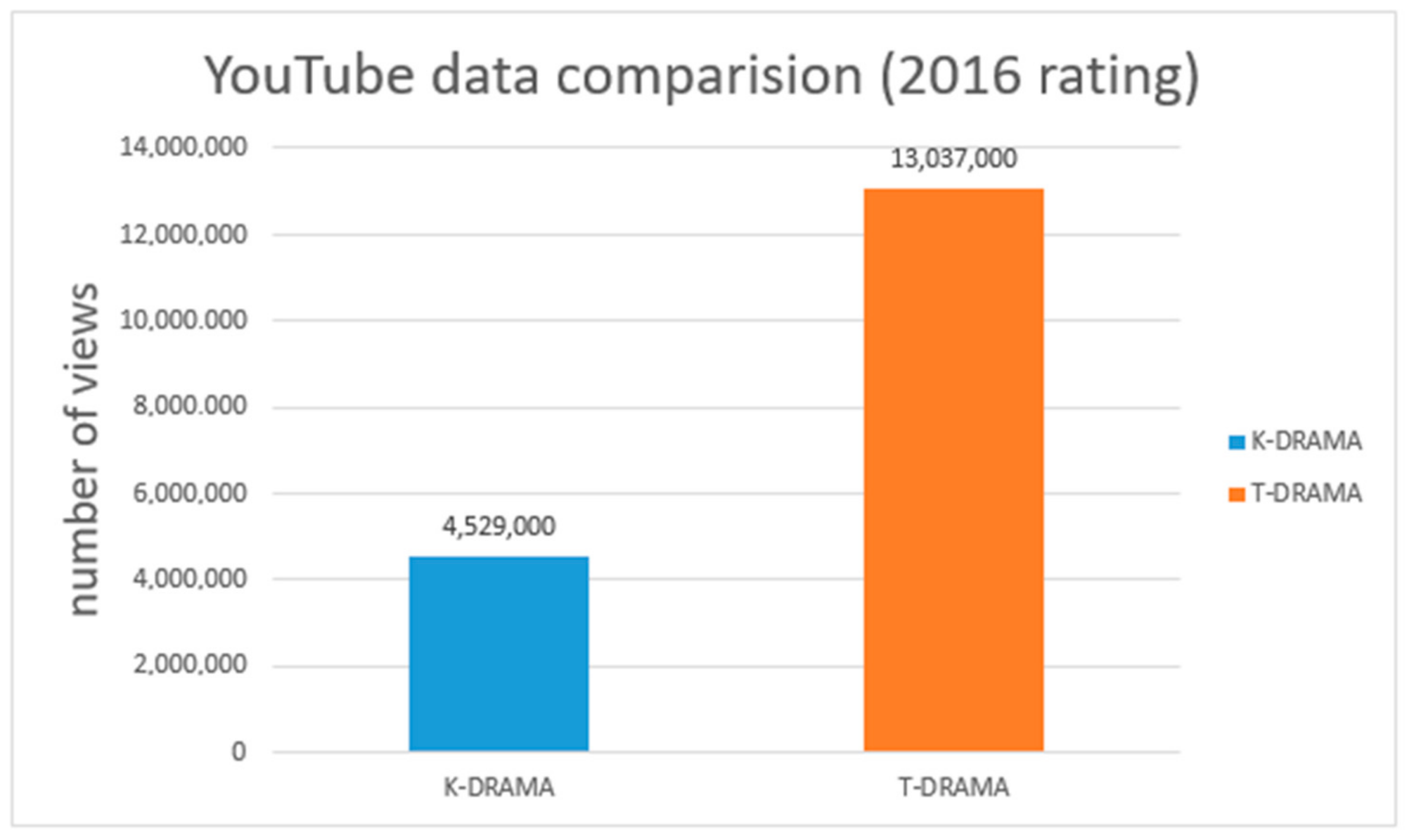

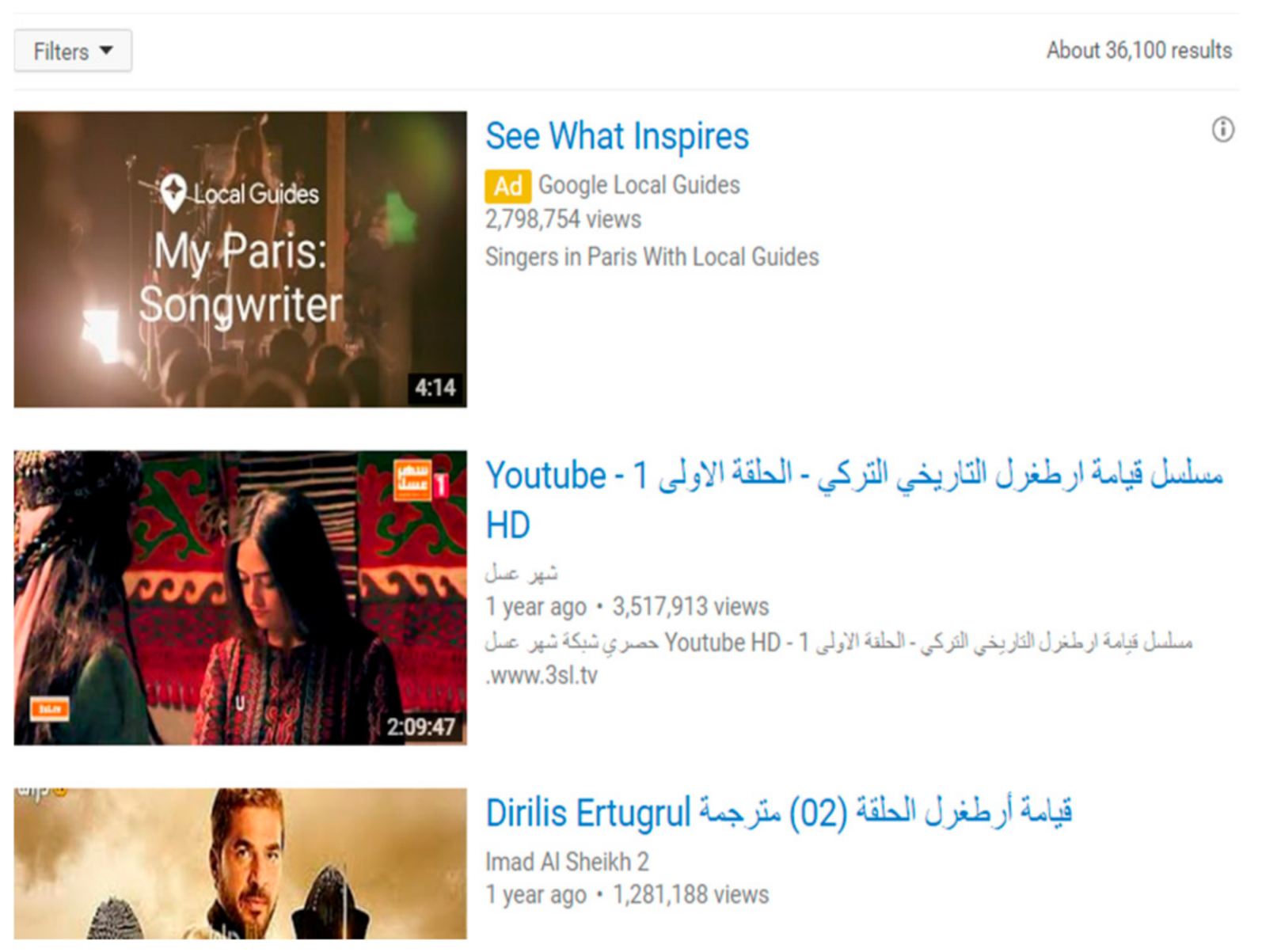

A search on YouTube in November–December 2016, using the same keywords and same procedures for analysing the data, revealed the following (search entry “Korean drama” and “Turkish drama”; method used: view-count factor, yet narrowing our scope to 2016 only) (see

Figure 7).

Enthralled by the huge success of

Goblin (Korean drama) and

Diriliş: Ertuğrul (Turkish drama) in 2016–17, I decided to have another look. The findings of this most recent research, however, do not affect the outcome of the paper, i.e., that Korean drama and K-pop are doing very well in Asia (mainly South Asia), while Turkish drama is taking the lead from its Korean counterpart in the Middle East region (see

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

Finally, it might be apt here to refer to the benefits

Hallyu has for Korea in general and the Korean economy in particular. In this regard, many scholars who write on

Hallyu have referred to the influence it has had on the export of Korean products overseas. For example, Kim argues that

Hallyu has increased Korean car exports to the Middle East (where the USA and Japan were the main players) since 2007 [

2] (p. 18). She adds that, after the success of Korean drama in the Middle East, the export of Korean products jumped dramatically in Iraq, KSA and Iran in 2011; it increased by 7716%, 239% and 110%, respectively [

2] (p. 19). In a similar vein, Sue Jin Lee states that “The Korean Wave has undoubtedly had many positive implications for Korea, such as improving foreign relations increasing tourism and an overall enhancement of the Korean image on the international stage [

32] (p. 89). Lee Won-jun [

33] (pp. 79–82) and Mun Seong Choi [최문성] [

34] (pp. 6–88) reiterate the same ideas, confirming that

Hallyu had a positive impact on Korean exports.

Yurena Kalshoven argues that using

Hallyu as a “soft power” was a goal of many Korean presidents but mainly materialized during the reign of Lee Myun Bak [

35] (p. 3). It is no exaggeration to say that

Hallyu can play an important role in enhancing the image of Asia and Korea in the world. Here I agree with, among many others, Kim [

2], Lee [

32] and Mōri [

36]. In this concern, Mōri argues that her mother (Mōri and her mother are Japanese) had a nasty prejudice against “Korea and Korean people” before watching

Winter Sonata. After watching the drama, her attitude changed completely and she even travelled to Korea and visited the place where scenes from the drama wer shot [

36] (p. 127). According to Hirata, K-drama and K-pop resulted in an increase in Japanese, especially women, tourists to Korea, including filming locations [

37] (pp. 143, 148). The number of medical tourists has jumped from about 8000 in 2000 to 80,000 in 2010 and is expected to reach 400,000 in 2016 [

2] (p. 26). Plastic and heart surgery procedures accounted for a major fraction of these visits, and it seems that Korea is on its way to surpassing other pioneering countries in this field. In this regard, Su Wan Kim argues that Korea has already surpassed the neighbouring Asian countries of Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia when it comes to medical tourism revenues [

2] (pp. 25–26). Lee [

32] (p. 89) argues that “the most conspicuous effect the Korean Wave has had on South Korea was enhancing its overall national image.” Speaking about the tremendous effect “Gangnam Style” has had on the world, Shin Hyun-kwan (MNET owner), in an interview with Hong, said, “The actor Brue Lee changed Westerners’ ideas about Asians. PSY is doing the same thing for Koreans” [

8] (p. 133).

Many scholars who have written on the spread of

Hallyu in Asia and across the world have referred to the positive effects

Hallyu might have in terms of cementing firmer and friendlier relations between Asian countries and beyond. Keehyeung Lee [

38] (pp. 175–189) and Jeong-Nam Kim and Lan Ni [

39] (pp. 132–154) share the same idea [Lan Ni was sometimes referenced as S. Ni but in an email to the author she confirmed that the correct citation should be Lan Ni]. Jang and Paik agree that “The Korean Wave has had a positive impact and potential that would promote Korea’s cultural diplomacy as a part of soft power approach” [

40] (p. 203). Accordingly, Young Eun Chae argues that the success

Winter Sonata achieved in Japan may help in re-examining “Korea’s troubling relationship with Japan and the critical position Japan occupies for the formation of Korea’s national identity” [

21] (p. 192). In a similar vein, Kuwahara argues that the soap opera

Winter Sonata had a tremendous effect on Japanese audiences when it was aired in Japan in 2003. Kuwahara thinks the Korean Wave may help in reshaping Korean‒Japanese relations [

9] (p. 7). Hyejung Ju [

11] (p. 34) also explores this idea. The new relationship between Korea and Japan seems to have eased the inherited mutual hatred and misunderstanding between the nations. This is clear in the fact that, for example, of the total

$80.9 million of Korean music exports in 2010, according to Jin, “Japan constituted as much as 75.8 percent of those sales, up from 69.1 percent in 2009” [

4] (p. 119). What is more, Hong [

8] (p. 98) believes that

Hallyu may be a leading force that one day might bring peace and stability to the Korean peninsula, i.e., between North Korea and South Korea. Similarly, Bae et al. [

41] state that

Hallyu had enormous effects on the Korean economy and that it has helped increase the numbers of tourists who come to visit Korea. Shim and Molen argue that the Korean Wave can play a significant role in helping ease tensions between nations with strained relationships [

10] (p. 30); [

5] (p. 158). Jung and Paik argue that

Hallyu is not 100% Korean; rather, it comprises other international (American, European and Asian) components so could be called the “Korean hybrid wave”: “The Korean Wave is not a ‘Korean’ wave, rather it is a hybrid of traditional Korean cultures and Western cultures, particularly American” [

40] (pp. 200–201).

6. Conclusions

As has been noted, Korea learned a lesson from the financial hardship that hit the country, and other Asian countries, in 1997. I argue that the lesson Koreans learned is that they must not live at the mercy of the

chaebols. As early as 2005, it became clear that

Hallyu was helping the Korean economy to flourish. In a report released by the Trade Research Institute (TRI), there are indications that

Hallyu boosted Korea’s GDP by

$1.87 billion (0.2%) in 2004 (see, for example, “

Hallyu boosts Korea’s GDP by 0.2%,” available at:

www.visitkorea.or.kr, 3 May 2005, (site visited on 27 October 2016)). The success of

Hallyu has so far garnered billions of U.S. dollars for the Korean Treasury and also accelerated the sales of Korean cars, mobile phones and fashion products in many different parts of the globe. In a similar vein, the

Hallyu phenomenon has increased the number of tourists who come to Korea either for leisure or medical purposes.

To conclude, in this paper I examined the beginnings, the rise and the development of Hallyu, mainly in Asia and the Middle East. Regarding the reception of Hallyu in the Middle East, I gave reasons why Hallyu has been doing remarkably well in Asia yet has achieved only marginal success in the Middle East. When it comes to the future of Hallyu in the Middle East, I argued that K-drama and K-pop are competing with Turkish drama. The charts I compiled indicated that Turkish drama is ahead of Korean drama in the Middle East, while Korean drama is far ahead of Turkish drama in Asia. It is clear that geographical, social and cultural factors played an important role in the success that Korean drama and Turkish drama have achieved in Asia and the Middle East, respectively.