How Organizational Resources and Managerial Features Affect Business Performance: An Analysis in the Greek Wine Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Gap

1.3. Aim of the Study and Contribution

2. Analytical Context

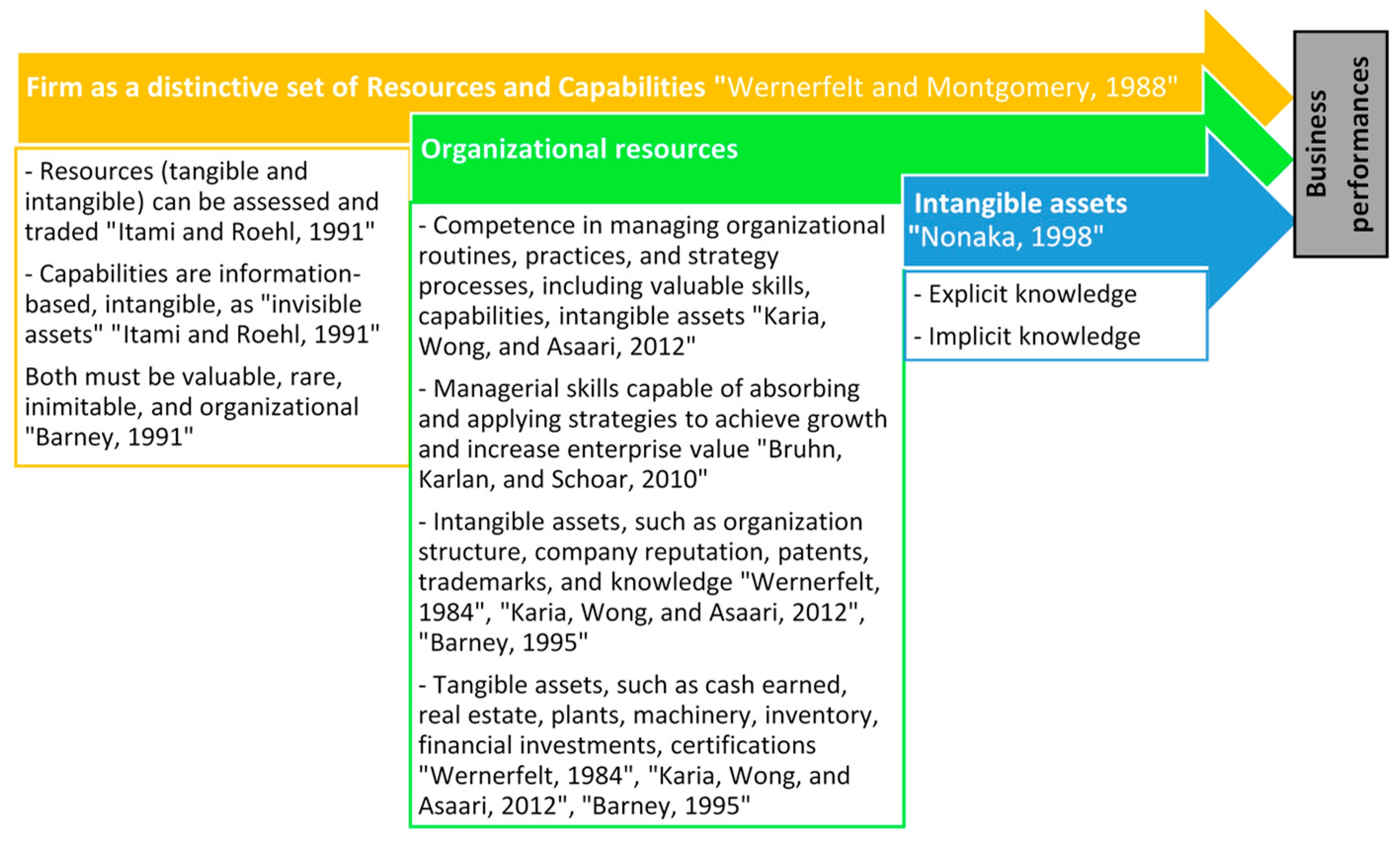

2.1. Theoretical Framework

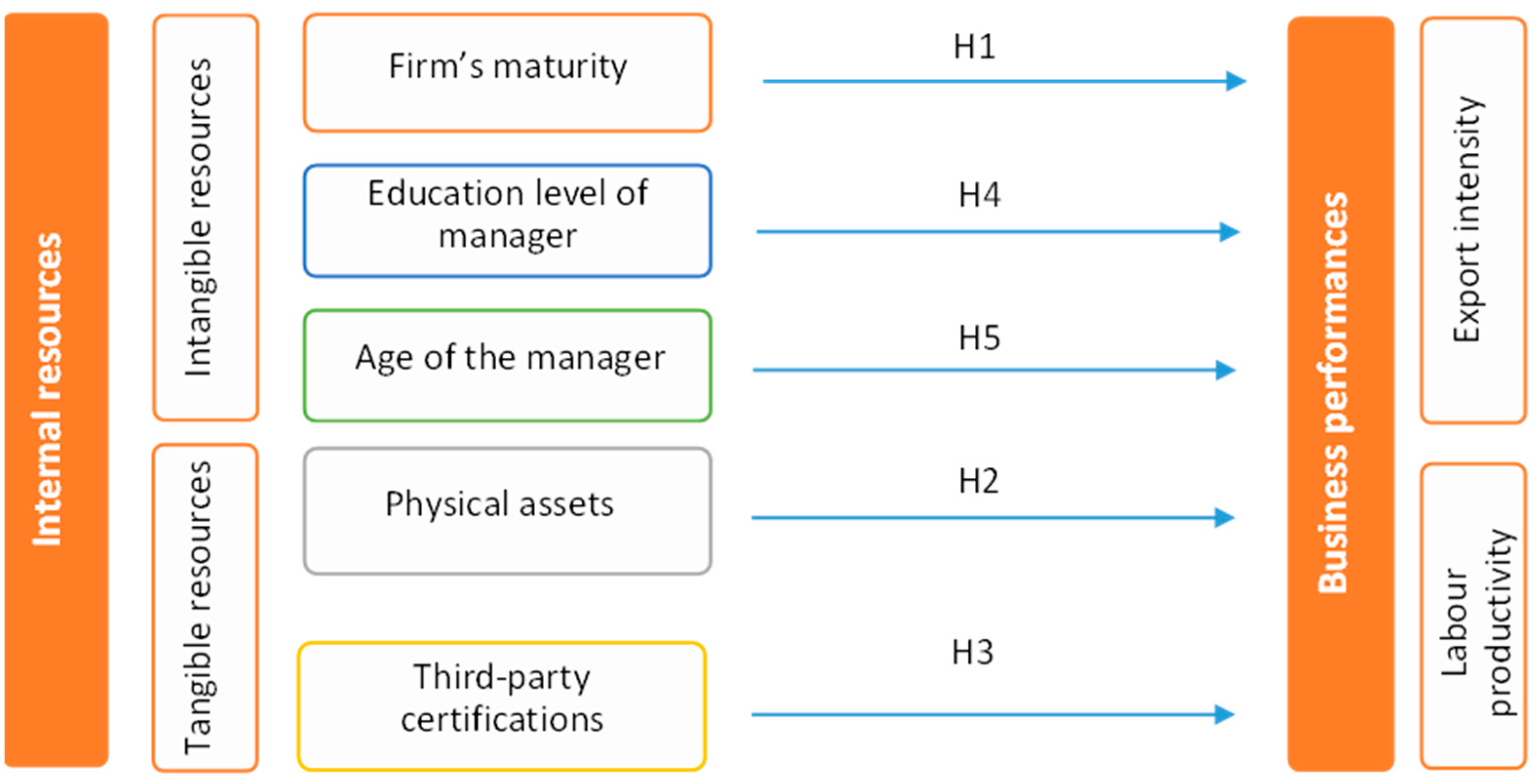

2.2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. Questionnaire Development

3.2. Sample

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Will Sustainability Shape the Future Wine Market? Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Nelgen, S.; Pinilla, V. Global Wine Markets, 1860 to 2016: A Statistical Compendium; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; ISBN 9781925261660. [Google Scholar]

- Hannin, H. Breeding, Consumers and Market Issues: Main Evolutions in the Vine and Wine Industry. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1248, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesano, G.; di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Gioacchino, P.; D’Amico, M. What’s in Organic Wine Consumer Mind? A Review on Purchasing Drivers of Organic Wines. Wine Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Alibrandi, A.; Zirilli, A.; Sakka, G.; Giannetto, C. Analysis of the Wine Consumer’s Behavior: An Inferential Statistics Approach. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Thrassou, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Schifani, G.; Galati, A. Factors Affecting Consumer Preferences for “Natural Wine”. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2463–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Dubernet, M.; Duchêne, E.; Gowdy, M.; Marguerit, E.; Pieri, P.; Parker, A.; de Rességuier, L.; Ollat, N. An Update on the Impact of Climate Change in Viticulture and Potential Adaptations. Agronomy 2019, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.-T.; Correia, C.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Dibari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; et al. A Review of the Potential Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Options for European Viticulture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, E.; Migliore, G.; di Franco, C.P.; Borsellino, V. Is There Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Wine Industry? Exploring Sicilian Wineries Participating in the SOStain Program. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Borsellino, V.; Crescimanno, M.; Pisano, G.; Schimmenti, E. Implementation of Green Harvesting in the Sicilian Wine Industry: Effects on the Cooperative System. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Galati, A.; Schimmenti, E. Survey on the Innovation in the Sicilian Grapevine Nurseries. J. Wine Res. 2012, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Varia, F.; Zinnanti, C.; Schimmenti, E. The Sicilian Cooperative System of Wine Production. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2020, 32, 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Tinervia, S.; Iliopoulos, C.; Theodorakopoulou, I. Internal Resources as Tools to Increase the Global Competition: The Italian Wine Industry Case. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2406–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomarra, M.; Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Vrontis, D. Geographical Cues: Evidences from New and Old World Countries’ Wine Consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Krajsic, V. Exporting Wine in Complex Times: A Study among Small and Medium Wineries. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasekera, R.; Bianchi, C.C. Management Characteristics and the Decision to Internationalize: Exploration of Exporters vs. Non-Exporters within the Chilean Wine Industry. J. Wine Res. 2013, 24, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutot, V.; Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L. Information Management for the Internationalization of SMEs: An Exploratory Study Based on a Strategic Alignment Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Sato, M. The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 11, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.G.; Pun, K.F.; Lalla, T.R.M. An AHP-based Study of TQM Benefits in ISO 9001 Certified SMEs in Trinidad and Tobago. TQM Mag. 2005, 17, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, H. Strategic Marketing Management: Achieving Superior Business Performance through Intelligent Marketing Strategy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.R.F.; Rubio, M.T.M.; Garcés, S.A. The Competitive Advantage in Business, Capabilities and Strategy. What General Performance Factors Are Found in the Spanish Wine Industry? Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri Behmiri, N.; Rebelo, J.F.; Gouveia, S.; António, P. Firm Characteristics and Export Performance in Portuguese Wine Firms. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 419–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.; Costa, R.; Gonçalves, R. Exploring the Determinants of Wine Export Performance. Analyzing the Importance of Noneconomic Performance. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinga, M.H.; Ngqangweni, S.; van der Walt, S.; Potelwa, Y.; Nyhodo, B.; Phaleng, L.; Ntshangase, T. Geographical Indications in the Wine Industry: Does It Matter for South Africa? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2021, 33, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistiche Nazionali|OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/it/what-we-do/country-report?oiv (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Vlachos, V.A. A Macroeconomic Estimation of Wine Production in Greece. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, C. Barriers to the Export of Greek Wine. In Proceedings of the 113th EAAE Seminar: A Resilient European Food Industry and Food Chain in a Challenging World, Chania, Crete, 3 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karelakis, C.; Mattas, K.; Chryssochoidis, G. Export Problems Perceptions and Clustering of Greek Wine Firms. EuroMed J. Bus. 2008, 3, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-Based Theories of Competitive Advantage: A Ten-Year Retrospective on the Resource-Based View. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, D. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation; John Murray: London, UK, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Special Theory Forum the Resource-Based Model of the Firm: Origins, Implications, and Prospects. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Clark, D.N. Resource-Based Theory: Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage; Oup Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B.; Montgomery, C.A. Tobin’s q and the Importance of Focus in Firm Performance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1988, 78, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Itami, H.; Roehl, T.W. Mobilizing Invisible Assets; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Gaining and Sustaining a Competitive Advantage. In Introduction to e-Business; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- Karia, N.; Wong, C.Y.; Asaari, M.H.A.H. Typology of Resources and Capabilities for Firms’ Performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 65, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mwai, G.M.; Namada, J.M.; Katuse, P. Influence of Organizational Resources on Organizational Effectiveness. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 1634–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Karlan, D.; Schoar, A. What Capital Is Missing in Developing Countries? Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontis, N. Assessing Knowledge Assets: A Review of the Models Used to Measure Intellectual Capital. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2001, 3, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Looking inside for Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1995, 9, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic Assets and Organizational Rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Research Directions for Knowledge Management. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. The Knowledge-Creating Company. In The Economic Impact of Knowledge; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1998; pp. 175–187. ISBN 9780080505022. [Google Scholar]

- Brouthers, L.E.; Nakos, G.; Hadjimarcou, J.; Brouthers, K.D. Key Factors for Successful Export Performance for Small Firms. J. Int. Mark. 2009, 17, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aziz, A.; Abdul Hamid, S.N. Determinants of SME Export Performance. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2017, 1, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, L.M. Internationalization vs Family Ownership and Management: The Case of Portuguese Wine Firms. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Ø. The Relationship Between Firm Size, Competitive Advantages and Export Performance Revisited. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 1999, 18, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; López-Fernández, M.C.; Garcia-Piqueres, G. Analysis of the Relationship between Sources of Knowledge and Innovation Performance in Family Firms. Innovation 2016, 18, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, M.F. The Determinants of Internationalization: Evidence from the Wine Industry. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.; Brouthers, L.E. Trade Promotion and SME Export Performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2006, 15, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majocchi, A.; Bacchiocchi, E.; Mayrhofer, U. Firm Size, Business Experience and Export Intensity in SMEs: A Longitudinal Approach to Complex Relationships. Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Ortega, S.M.; Álamo-Vera, F.R. SMES’ Internationalization: Firms and Managerial Factors. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.C.; Shipilov, A.V. Ecological Approaches to Organizations Strategic Organization View Project Organizational Creativity View Project; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A.P.; Sfakianaki, E. Impacts of ISO 9000 on Greek SMEs Business Performance. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 2248–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D.P.; Gotzamani, K.D. Critical Factors, Food Quality Management and Organizational Performance. Food Control 2014, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffham, A.; Karehu, E.; MacGregor, J. Impact of GLobalGAP on Small-Scale Vegetable Growers in Kenya. Fresh Perspect. 2007, 78, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chkanikova, O.; Sroufe, R. Third-Party Sustainability Certifications in Food Retailing: Certification Design from a Sustainable Supply Chain Management Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschuch, C.; Wollni, M.; Villalobos, P. Adoption of Food Safety and Quality Standards among Chilean Raspberry Producers—Do Smallholders Benefit? Food Policy 2013, 40, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Maertens, M. The Impact of Private Food Standards on Developing Countries’ Export Performance: An Analysis of Asparagus Firms in Peru. World Dev. 2015, 66, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Determinants of Export Intensity in Emerging Markets: An Upper Echelon Perspective. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Pointon, J.; Abdou, H. Factors Influencing the Propensity to Export: A Study of UK and Portuguese Textile Firms. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, A.; Michałek-European, A.; Bank, C.; Jakub, J. Determinants of Export Performance: Comparison of Central European and Baltic Firms. Financ. A Úvěr-Czech J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 65, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Lejpras, A. Determinants of Export Performance: Differences between Service and Manufacturing SMEs. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenzon, S.; Shamshur, A.; Zarutskie, R. CEO’s Age and the Performance of Closely Held Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 917–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensley, M.D.; Pearson, A.; Pearce, C.L. Top Management Team Process, Shared Leadership, and New Venture Performance: A Theoretical Model and Research Agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotorri, M.; Krasniqi, B.A. Managerial Characteristics and Export Performance—Empirical Evidence from Kosovo. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 13, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SFA20/2022 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Anastasiadis, F.; Alebaki, M. Mapping the Greek Wine Supply Chain: A Proposed Research Framework. Foods 2021, 10, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, C. Determinants of Export Performance in French Wine SMEs. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Tinervia, S.; Tulone, A.; Crescimanno, M. Drivers Affecting the Adoption and Effectiveness of Social Media Investments. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, J.G.; Sampedro, E.L.-V.; Feliu, V.R.; Sánchez, M.B.G. Management Control Systems and ISO Certification as Resources to Enhance Internationalization and Their Effect on Organizational Performance. Agribusiness 2013, 29, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, F.; Eunni, R.V.; Fouto, N.M.M.D.; Felisoni de Angelo, C. Impact of ISO 9000 Certification on Firm Performance: Evidence from Brazil. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 974–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, B.; Wei, Z.; Xie, F. ISO Certification, Financial Constraints, and Firm Performance in Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Glob. Financ. J. 2014, 25, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of Eco-Innovations: Reflections from Selected Case Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A.; Santini, C.; Lazzeretti, L.; Eyler, R. Desperately Seeking Serendipity. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Liu, C.; Lu, J.; Cao, J. Impacts of ISO 14001 Adoption on Firm Performance: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 32, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafel, P.; Sikora, T. Quality management sysytems benefits and their influence on financial performance. In Proceedings of the 6th International Quality Conference, Kragujevac, Serbia, 8 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tihanyi, L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R. Composition of the Top Management Team and Firm International Diversification. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1157–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M.F.; Bantel, K.A. Top Management Team Demography and Corporate Strategic Change. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, P.L.; Silvestri, R.; Lamonaca, E.; Faccilongo, N. Relational Abilities as Critical Resources for Value Creation in Wine Supply Chain of Basilicata. Econ. Agro-Aliment./Food Econ. 2017, 19, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aali, A.; Lim, J.-S.; Khan, T.; Khurshid, M. Marketing Capability and Export Performance: The Moderating Effect of Export Performance. South Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 44, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenzadeh, M.; Ahmadian, S. The Mediating Role of Competitive Strategies in the Effect of Firm Competencies and Export Performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 36, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hultman, M.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Robson, M.J. Export Promotion Strategy and Performance: The Role of International Experience. J. Int. Mark. 2011, 19, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.Y.; Gao, G.Y.; Kotabe, M. Market Orientation and Performance of Export Ventures: The Process through Marketing Capabilities and Competitive Advantages. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n = 41 | |

|---|---|---|

| Legal form (%) | Individual firms | 68.3 |

| Companies and cooperatives | 31.7 | |

| Physical size * | Number of permanent workers | 6.0 (1.0; 18.0) |

| Number of bottles (,000) | 232.5 (1.9; 1000) | |

| Economic size * | Turnover (,000 euro) | 709.0 (6.7; 4700) |

| Experience * | Number of years | 32.8 (5.0; 106.0) |

| Certified wineries (%) | % of wineries adopting third-party voluntary certifications | 51.2 |

| Participation in wine fair * | No. of time in a year | 2.1 (0.0; 5.0) |

| Experience in export * | No. of years | 15.6 (0.0; 56.0) |

| n = 41 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (%) | <40 years old | 9.8 |

| 40–65 years old | 78.0 | |

| >65 years old | 12.2 | |

| Level of education (%) | High school diploma | 12.2 |

| Bachelor level and master’s degree | 87.8 | |

| Experience in the sector * | No. of years | 25.9 (4.0; 45.0) |

| Cluster | No. of Cases | Export Experience | Size | Age of the Winery | Level of Education | Direct Sale | Promotion and Advertising | QC | EC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 14.36 | 6.09 | 21.54 | 3.90 | 61.27 | 2.09 | 0.72 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 7 | 5.00 | 4.57 | 21.71 | 3.57 | 98.57 | 2.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 6 | 32.83 | 7.33 | 92.00 | 4.00 | 34.17 | 1.83 | 0.50 | 0.17 |

| 4 | 17 | 14.70 | 6.59 | 23.76 | 3.94 | 17.06 | 2.17 | 0.41 | 0.17 |

| Cluster | Error | df | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Square between Groups | df | Mean Square within Groups | ||||

| Direct Sale | 36,973.549 | 3 | 6665.671 | 37 | 68.411 | 0.000 |

| Age of the winery | 24,669.224 | 3 | 5731.215 | 37 | 53.087 | 0.000 |

| Export in experience | 2598.848 | 3 | 5110.908 | 37 | 6.271 | 0.001 |

| Educational level | 0.826 | 3 | 3.565 | 37 | 2.857 | 0.050 |

| QC | 0.730 | 3 | 9.514 | 37 | 0.947 | 0.428 |

| EC | 0.319 | 3 | 5.486 | 37 | 0.718 | 0.548 |

| Size | 28.950 | 3 | 962.074 | 37 | 0.371 | 0.774 |

| Promotion and advertising | 0.567 | 3 | 46.213 | 37 | 0.151 | 0.928 |

| N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor Productivity | |||

| Certified wineries | 21 | 21.45 | 450.50 |

| Not-certified wineries | 20 | 20.53 | 410.50 |

| Export Intensity | |||

| Certified wineries | 21 | 24.26 | 509.50 |

| Not-certified wineries | 20 | 17.58 | 351.50 |

| LP | EI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 200.500 | 141.500 | ||

| Z | −0.248 | −1.791 | ||

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.804 | 0.073 | ||

| Monte Carlo Sig. (2-tailed) | Sig. | 0.805 | 0.072 | |

| 99% Confidence Interval | Lower bound | 0.795 | 0.065 | |

| Upper bound | 0.815 | 0.079 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crescimanno, M.; Mirabella, C.; Borsellino, V.; Schimmenti, E.; Vrontis, D.; Tinervia, S.; Galati, A. How Organizational Resources and Managerial Features Affect Business Performance: An Analysis in the Greek Wine Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043522

Crescimanno M, Mirabella C, Borsellino V, Schimmenti E, Vrontis D, Tinervia S, Galati A. How Organizational Resources and Managerial Features Affect Business Performance: An Analysis in the Greek Wine Industry. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043522

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrescimanno, Maria, Claudio Mirabella, Valeria Borsellino, Emanuele Schimmenti, Demetris Vrontis, Salvatore Tinervia, and Antonino Galati. 2023. "How Organizational Resources and Managerial Features Affect Business Performance: An Analysis in the Greek Wine Industry" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043522