Clinical Depression in the Last Year in Life in Persons Dying from Non-Cancer Conditions—Real World Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population

2.3. Variables

2.4. Definition of Main Diagnosis

2.5. Selection Bias and Dropouts

2.6. Study Size

2.7. Statistical Methods and Missing Data

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

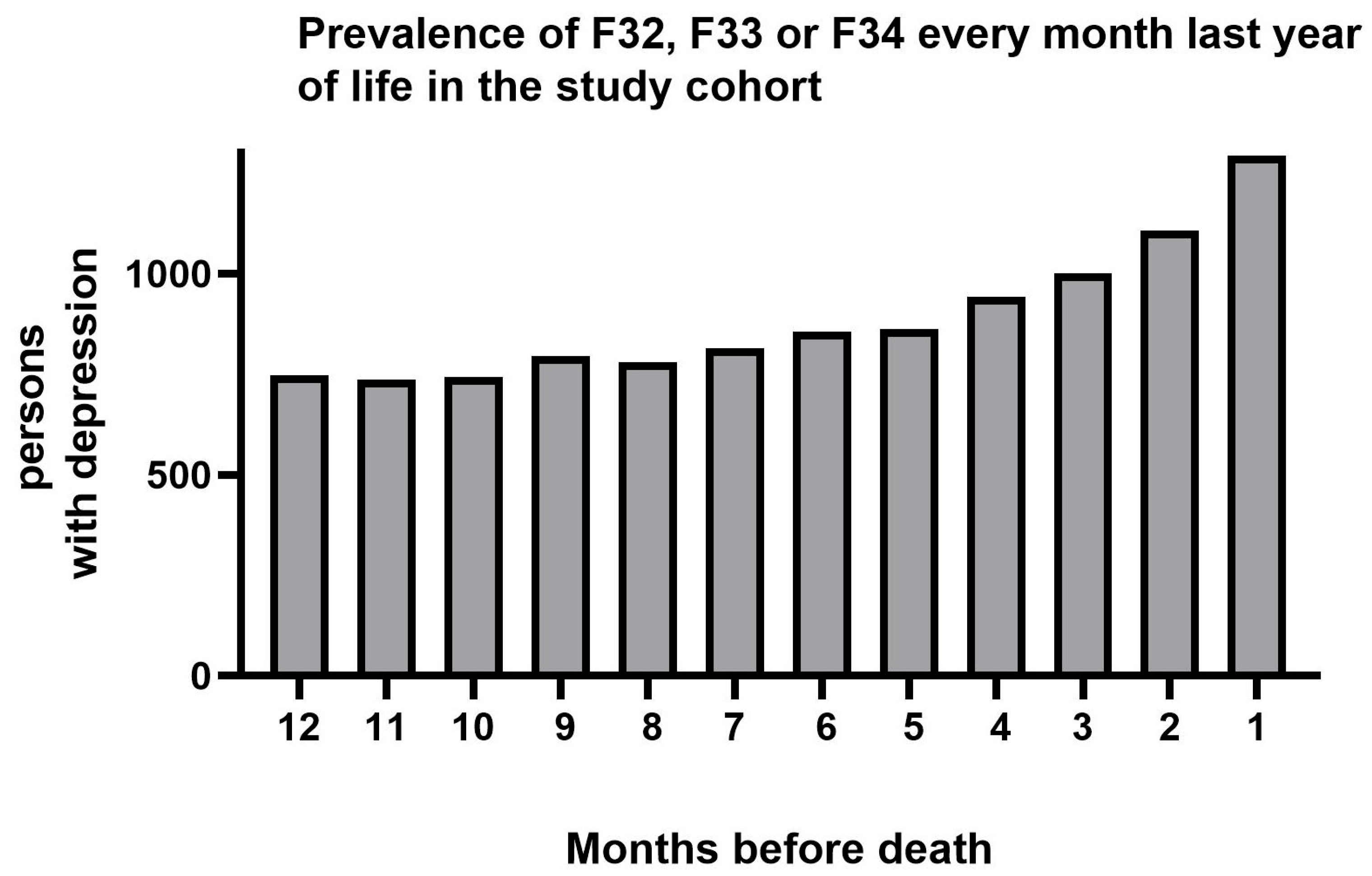

3.2. Prevalence of Depression

3.3. Health Care Consumption

3.4. Regression Analyses

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Variables

4.2. Specific Diagnoses

4.3. Healthcare Utilization

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| EOL | End-of-life |

| ICD-10 | International classification of diseases 10th revision |

| Mosaic | A socioeconomic measure on area level |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| SPC | Specialized palliative care |

References

- Chochinov, H.M. Depression in cancer patients. Lancet Oncol. 2001, 2, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Chan, M.; Bhatti, H.; Halton, M.; Grassi, L.; Johansen, C.; Meader, N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, L.; Loge, J.H.; Wasteson, E.; Higginson, I.J.; Epcrc, E.P.C.R.C. The detection of depression in palliative care. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2009, 3, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasteson, E.; Brenne, E.; Higginson, I.J.; Hotopf, M.; Lloyd-Williams, M.; Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; European Palliative Care Research, C. Depression assessment and classification in palliative cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Palliat. Med. 2009, 23, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, P.; Schultz, T. High Frequency of Depression in Advanced Cancer with Concomitant Comorbidities: A Registry Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salk, R.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Abramson, L.Y. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 783–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.T.; Thorp, J.G.; Huider, F.; Grimes, P.Z.; Wang, R.; Youssef, P.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Byrne, E.M.; Adams, M.; Consortium, B.; et al. Sex-stratified genome-wide association meta-analysis of major depressive disorder. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nöbbelin, L.; Bogren, M.; Mattisson, C.; Bradvik, L. Incidence of melancholic depression by age of onset and gender in the Lundby population, 1947–1997. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejtzen, N.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K.; Li, X. Depression and anxiety in Swedish primary health care: Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 264, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, A.; Madden, R.A.; Whalley, H.C.; Reynolds, R.M.; Lawrie, S.M.; McIntosh, A.M.; Iveson, M.H. Socioeconomic status and depression-a systematic review. Epidemiol. Rev. 2025, 47, mxaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, B.; Åkesson, E.; Lökk, J.; Schultz, T.; Strang, P.; Franzén, E. Health care utilization at the end of life in Parkinson’s disease: A population-based register study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, P.; Schultz, T.; Strang, P. Specialized Palliative Care for Patients with Chronic Heart Failure at End of Life: Transfers, Emergency Department Visits, and Hospital Deaths. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 26, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strang, P.; Furst, P.; Hedman, C.; Bergqvist, J.; Adlitzer, H.; Schultz, T. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer: Access to palliative care, emergency room visits and hospital deaths. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strang, P.; Schultz, T.; Ozanne, A. Partly unequal receipt of healthcare in last month of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A retrospective cohort study of the Stockholm region. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 129, e9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, P.; Petzold, M.; Bjorkhem-Bergman, L.; Schultz, T. Differences in Health Care Expenditures by Cancer Patients During Their Last Year of Life: A Registry-Based Study. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 6205–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.D.; Lee, W.; Rayner, L.; Price, A.; Monroe, B.; Hansford, P.; Sykes, N.; Hotopf, M. Gender differences in prevalence of depression among patients receiving palliative care: The role of dependency. Palliat. Med. 2012, 26, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaj, D.; Schultz, T.; Strang, P. Nursing Home Residents With Dementia at End of Life: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Acute Hospital Deaths. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.B.; Mors, O.; Bertelsen, A.; Waltoft, B.L.; Agerbo, E.; McGrath, J.J.; Mortensen, P.B.; Eaton, W.W. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öfverholm, T.; Hasselgren, M.; Lisspers, K.; Nager, A.; Eliason, G.; Giezeman, M.; Janson, C.; Kisiel, M.A.; Montgomery, S.; Ställberg, B.; et al. High proportion of depression and anxiety in younger patients with COPD: A cross-sectional study in primary care in Sweden. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Schwebel, D.C.; Huang, Y.; Ning, P.; Cheng, P.; Hu, G. Sex-specific and age-specific suicide mortality by method in 58 countries between 2000 and 2015. Inj. Prev. 2021, 27, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, H.; Mehlum, L.; Titelman, D.; Isometsa, E.; Erlangsen, A.; Nordentoft, M.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Hokby, S.; Tomasson, H.; Palsson, S.P. Nordic region suicide trends 2000–2018; sex and age groups. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2023, 77, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/psykisk-halsa-och-suicidprevention/suicidprevention/statistik-om-suicid/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Nagy, A.; Schrag, A. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2019, 126, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmer, M.H.M.; van Beek, M.; Bloem, B.R.; Esselink, R.A.J. What a neurologist should know about depression in Parkinson’s disease. Pract. Neurol. 2017, 17, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijnders, J.S.; Ehrt, U.; Weber, W.E.; Aarsland, D.; Leentjens, A.F. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.A.; Tosin, M.H.S.; Warner-Rosen, T.; Afshari, M.; Barton, B.; Fleisher, J.E.; Hall, D.A.; Kirby, A.E.; Kompoliti, K.; Mahajan, A.; et al. Loneliness in Parkinson’s disease: Subjective experience overshadows objective motor impairment. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 136, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Bose, S.; Holbrook, J.T.; Nan, L.; Eakin, M.N.; Yohannes, A.M.; Wise, R.A.; Hanania, N.A. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With COPD and Comorbid Depression and Anxiety: Data From a National Multicenter Cohort Study. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2025, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, G.; Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S.; McGrail, M.; Garg, V.; Nasir, B. Depression and comorbid chronic physical health diseases in the Australian population: A scoping review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2025, 59, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.M.; Köhler-Forsberg, O.; Moss-Morris, R.; Mehnert, A.; Miranda, J.J.; Bullinger, M.; Steptoe, A.; Whooley, M.A.; Otte, C. Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Lu, L.; Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Wu, X.; Tang, G.; Ma, T.; Cheng, J.; Ran, P.; Zhou, Y. Associations of anxiety and depression with prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology 2025, 31, 2438553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi Kerahrodi, J.; Brähler, E.; Wiltink, J.; Michal, M.; Schulz, A.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; Toenges, G.; Lackner, K.J.; Pfeiffer, N.; et al. Association between medicated obstructive pulmonary disease, depression and subjective health: Results from the population-based Gutenberg Health Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Peng, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Z. Global prevalence and risk factors of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000 to 2022. J. Psychosom Res. 2023, 175, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corlateanu, A.; Covantsev, S.; Iasabash, O.; Lupu, L.; Avadanii, M.; Siafakas, N. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Depression-The Vicious Mental Cycle. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.E.; Nadali, J.; Parouhan, A.; Azarafraz, M.; Tabatabai, S.M.; Irvani, S.S.N.; Eskandari, F.; Gharebaghi, A. Prevalence of depression among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, C.; Fan, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, S.; Long, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Chang, L.; et al. Cardiovascular diseases and depression: A meta-analysis and Mendelian randomization analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4234–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, R.F.; Ferrari, F.; Moretti, A. Post-stroke depression: Mechanisms and pharmacological treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 184, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, K.; Nazir, A.; Wu, P.; Seitz, D.; Watt, J.A.; Goodarzi, Z. Depression detection in dementia: A diagnostic accuracy systematic review and meta analysis update. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Han, K.; Yoon, S.C.; Jeon, H.J. Variation in depression’s impact on dementia risk by age in adults aged ≥75 years. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 17, e70185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; Zhou, Y.; Marti, C.N. Possible and Probable Dementia and Depressive/Anxiety Symptoms: Mediation Effects of Social Engagement and Loneliness. Res. Aging 2025, 1640275251380531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojesson, A.; Brun, E.; Eberhard, J.; Segerlantz, M. Quality of life for patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer randomised to early specialised home-based palliative care: The ALLAN trial. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.; Siemens, W.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Antes, G.; Meffert, C.; Xander, C.; Stock, S.; Mueller, D.; Schwarzer, G.; Becker, G. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017, 357, j2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Pirl, W.F.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Back, A.L.; Kamdar, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Chittenden, E.H.; et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients With Lung and GI Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total n = 62,228 | Men n = 34,755 | Women n = 27,473 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 76.9 (14.9) | 74.7 (15.3) | 79.8 (13.9) |

| Age groups | |||

| 18–44 years, n (%) | 2564 (4.1) | 1779 (5.1) | 785 (2.9) |

| 45–64 years, n (%) | 7851 (12.6) | 5370 (15.5) | 2481 (9.0) |

| 65–74 years, n (%) | 11,565 (18.6) | 7191 (20.7) | 4374 (15.9) |

| 75–84 years, n (%) | 18,264 (29.3) | 10,460 (30.1) | 7804 (28.4) |

| 85 years or more, n (%) | 21,984 (35.3) | 9955 (28.6) | 12,029 (43.8) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Heart failure | 8330 (13.4) | 4542 (13.1) | 3788 (13.8) |

| COPD | 4466 (7.2) | 2014 (5.8) | 2452 (8.9) |

| Stroke | 3859 (6.2) | 1861 (5.4) | 1998 (7.3) |

| Dementia | 2172 (3.5) | 1058 (3.0) | 1114 (4.1) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 593 (1.0) | 391 (1.1) | 202 (0.7) |

| ALS | 501 (0.8) | 279 (0.8) | 222 (0.8) |

| Other diagnosis | 42,307 (68.0) | 24,610 (70.8) | 17,697 (64.4) |

| Mosaic-Socioeconomics | |||

| Group 1, n (%) | 14,615 (23.5) | 8144 (23.4) | 6471 (23.6) |

| Group 2, n (%) | 23,735 (38.1) | 13,647 (39.3) | 10,088 (36.7) |

| Group 3, n (%) | 23,878 (38.4) | 12,964 (37.3) | 10,914 (39.7) |

| SPC | |||

| Yes | 10,522 (16.9) | 5179 (14.9) | 5343 (19.5) |

| No | 51,706 (83.1) | 29,576 (85.1) | 22,130 (80.5) |

| Variables | Total n = 62,228 | Depression n = 4391 | No Depression n = 57,837 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (sd) | 76.9 (14.9) | 71.6 (18.4) | 77.3 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Age groups | <0.001 | |||

| 18–44 years, n (%) | 2564 | 469 (18.3) | 2095 (81.7) | |

| 45–64 years, n (%) | 7851 | 836 (10.7) | 7015 (89.3) | |

| 65–74 years, n (%) | 11,565 | 702 (6.1) | 10,863 (93.9) | |

| 75–84 years, n (%) | 18,264 | 1124 (6.2) | 17,140 (93.8) | |

| 85 years or more, n (%) | 21,984 | 1260 (5.7) | 20,724 (94.3) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Women, n (%) | 27,473 | 2205 (8.0) | 25,268 (92.0) | |

| Men n (%) | 34,755 | 2186 (6.3) | 32,569 (93.7) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 593 | 56 (9.4) | 537 (90.6) | |

| COPD | 4466 | 366 (8.2) | 4100 (91.8) | |

| ALS | 501 | 35 (7.0) | 466 (93.0) | |

| Stroke | 3859 | 258 (6.7) | 3601 (93.3) | |

| Dementia | 2172 | 133 (6.1) | 2039 (93.9) | |

| Heart failure | 8330 | 492 (5.9) | 7838 (94.1) | |

| Mosaic-Socioeconomics | 0.005 | |||

| Group 1, n (%) | 14,615 | 1118 (7.6) | 13,497 (92.4) | |

| Group 2, n (%) | 23,735 | 1619 (6.8) | 22,116 (93.2) | |

| Group 3, n (%) | 23,878 | 1654 (6.9) | 22,224 (93.1) | |

| SPC | 0.007 | |||

| Yes | 10,522 | 678 (6.4) | 9844 (93.6) | |

| No | 51,706 | 3713 (7.2) | 47,993 (92.8) | |

| Place of death | <0.001 | |||

| Acute hospitals, n (%) | 24,482 | 1477 (6.0) | 23,005 (94.0) | |

| Others, n (%) | 37,746 | 2914 (7.7) | 34,832 (92.3) |

| Variable | Depression | No Depression | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency room visits, n (%), last year of life | 3931/4391 (89.5) | 46,990/57,837 (81.3) | <0.001 |

| Emergency room visits, n (%), last 3 months of life | 3111/4391 (70.9) | 40,097/57,837 (69.3) | 0.03 |

| Emergency room visits, n (%), last month of life | 2389/4391 (54.4) | 32,697/57,837 (56.5) | 0.006 |

| Visits in psychiatric services, n (%), last year of life | 1816/4391 (41.4) | 5078/57,837 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Visits in psychiatric services, n (%), last 3 months of life | 1348/4391 (30.7) | 3544/57,837 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Visits in psychiatric services, n (%), last month of life | 1012/4391 (23.1) | 2555/57,837 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Univariable OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Multivariable aOR (95%CI) 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | ||||

| 18–44 years | 3.68 (3.28–4.13) | <0.0001 | 4.12 (3.66–4.63) | <0.0001 |

| 45–64 years | 1.96 (1.79–2.15) | <0.0001 | 2.17 (1.98–2.39) | <0.0001 |

| 65–74 years | 1.06 (0.97–1.17) | 0.21 | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 0.006 |

| 75–84 years | 1.08 (0.99–1.17) | 0.07 | 1.15 (1.05–1.24) | 0.003 |

| ≥85 years | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 1.30 (1.22–1.38) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.37–1.55) | <0.0001 |

| Men | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Mosaic groups 2 | ||||

| Group 1 | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 0.008 | 1.19 (1.10–1.29) | <0.0001 |

| Group 2 | 0.98 (0.92–1.01) | 0.65 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.40 |

| Group 3 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Model A: F32 Excluded, n = 1306 | Model B: F33 Excluded, n = 3566 | Model C: Nursing Homes Included, n = 7244 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Multivariable aOR (95%CI) 1 | p-Value | Multivariable aOR (95%CI) 2 | p-Value | Multivariable aOR (95%CI) 3 | p-Value |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 18–44 years | 8.70 (7.14–10.60) | <0.001 | 3.29 (2.89–3.75) | <0.001 | 4.21 (3.78–4.70) | <0.001 |

| 45–64 years | 5.28 (4.47–6.25) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.56–1.92) | <0.001 | 2.20 (2.02–2.38) | <0.001 |

| 65–74 years | 2.00 (1.66–2.41) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.96 | 1.23 (1.14–1.33) | <0.001 |

| 75–84 years | 1.52 (1.28–1.81) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.96–1.16) | 0.23 | 1.24 (1.17–1.32) | <0.001 |

| ≥85 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 1.59 (1.42–1.78) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.31–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) | <0.001 |

| Men | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Mosaic groups | ||||||

| Group 1 | 1.26 (1.09–1.45) | 0.002 | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | <0.001 |

| Group 2 | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 0.14 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 0.89 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.02 |

| Group 3 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Strang, P.; Alvariza, A.; Schultz, T.; Björkhem-Bergman, L. Clinical Depression in the Last Year in Life in Persons Dying from Non-Cancer Conditions—Real World Data. Diseases 2026, 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010009

Strang P, Alvariza A, Schultz T, Björkhem-Bergman L. Clinical Depression in the Last Year in Life in Persons Dying from Non-Cancer Conditions—Real World Data. Diseases. 2026; 14(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrang, Peter, Anette Alvariza, Torbjörn Schultz, and Linda Björkhem-Bergman. 2026. "Clinical Depression in the Last Year in Life in Persons Dying from Non-Cancer Conditions—Real World Data" Diseases 14, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010009

APA StyleStrang, P., Alvariza, A., Schultz, T., & Björkhem-Bergman, L. (2026). Clinical Depression in the Last Year in Life in Persons Dying from Non-Cancer Conditions—Real World Data. Diseases, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010009