Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Features in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

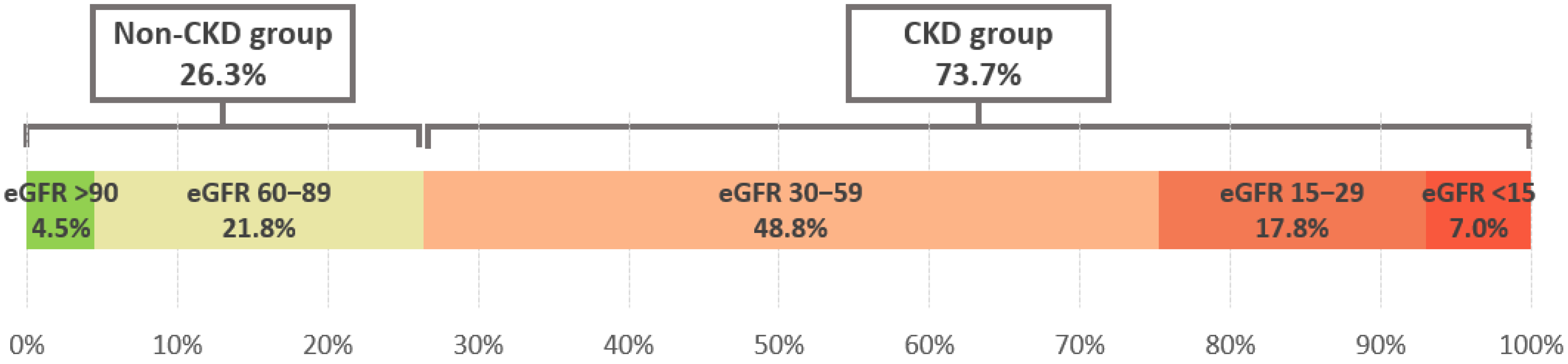

- CKD group with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2—heart failure patients with chronic kidney disease.

- Non-CKD group with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2—heart failure patients with preserved renal function [12].

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Laboratory Findings

3.4. Electrocardiography

3.5. Echocardiography

3.6. Therapy

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHF | Chronic heart failure |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRS | Cardiorenal syndrome |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HFmrEF | Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| SGLT2 | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

References

- Ronco, C.; Haapio, M.; House, A.A.; Anavekar, N.; Bellomo, R. Cardiorenal syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajibowo, A.O.; Okobi, O.E.; Emore, E.; Soladoye, E.; Sike, C.G.; Odoma, V.A.; Bakare, I.O.; Kolawole, O.A.; Okobi, E.; Chukwu, C.; et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, U.; Garimella, P.S.; Wettersten, N. Cardiorenal syndrome—Pathophysiology. Cardiol. Clin. 2019, 37, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaswami, J.; Bhalla, V.; Blair, J.E.; Chang, T.I.; Costa, S.; Lentine, K.L.; Lerma, E.V.; Mezue, K.; Molitch, M.; Mullens, W.; et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Classification, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e840–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, F.; Tiscornia, C.; Lorca-Ponce, E.; Aicardi, V.; Vasquez, S. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Molecular Pathways Linking Cardiovascular Dysfunction and Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Campbell, R.C. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease in Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2008, 4, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakopian, N.N.; Gharibian, D.; Nashed, M.M. Prognostic Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Heart Failure. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfman, I.; Szummer, K.; Dahlström, U.; Jernberg, T.; Lund, L.H. Associations with and prognostic impact of chronic kidney disease in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuegel, C.; Bansal, N. Heart failure in patients with kidney disease. Heart 2017, 103, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. A More Accurate Method to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine: A New Prediction Equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eknoyan, G.; Lameire, N.; Eckardt, K.; Kasiske, B.; Wheeler, D.; Levin, A.; Stevens, P.E.; Bilous, R.W.; Lamb, E.J.; Coresh, J.J.K.I. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsas, A.C.; Elzawawi, M.; Mavrogeni, S.; Boekels, M.; Khan, A.; Eldawy, M.; Stamatakis, I.; Kouris, D.; Daboul, B.; Gunkel, O.; et al. Heart Failure and Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Narrative Review on Pathophysiology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Regimens—From a Cardiologist’s View. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, R.; Nair, N.; Chakraborty, R.; Nemer, L.; Dasgupta, R.; Varian, K. An update on the pathophysiology and treatment of cardiorenal syndrome. Cardiol. Res. 2020, 11, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.R.; Hu, X.R.; Wang, W.D.; Zhou, Y. Cardiorenal syndrome: Clinical diagnosis, molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, A.; Mårtensson, J. Gender Differences in Patients with Heart Failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2003, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex and Gender Differences in Heart Failure. Int. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 2, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delco, A.; Portmann, A.; Mikail, N.; Rossi, A.; Haider, A.; Bengs, S.; Gebhard, C. Impact of Sex and Gender on Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 26, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Ashur, N.; Jones, A.D.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Bart, B.A.; Butler, J.; Chen, H.H.; Greene, S.J.; Reddy, Y.; Redfield, M.M.; et al. Implications of peripheral oedema in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A heart failure network analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. Causes and treatment of oedema in patients with heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, K.; Valente, M.A.E.; Voors, A.A.; O’Connor, C.M.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Hillege, H.L. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: An updated meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlister, F.A.; Ezekowitz, J.; Tonelli, M.; Armstrong, P.W. Renal insufficiency and heart failure: Prognostic and therapeutic implications from a prospective cohort study. Circulation 2004, 109, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.G.F.; Swedberg, K.; Follath, F.; Komajda, M.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Aguilar, J.C.; Dietz, R.; Gavazzi, A.; Hobbs, R.; Korewicki, J.; et al. The EuroHeart Failure survey programme—A survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2003, 24, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akchurin, O.M.; Kaskel, F. Update on Inflammation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Blood Purif. 2015, 39, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.; Lee, B.J.; Wei, J.; Weir, M.R. Hypertension in CKD: Core curriculum 2019. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 74, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.K.; Chang, T.I.; Cushman, W.C.; Furth, S.L.; Hou, F.F.; Ix, J.H.; Knoll, G.A.; Muntner, P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Sarnak, M.J.; et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Vaduganathan, M.; Khan, S.S.; Butler, J.; Gheorghiade, M. The vulnerable phase after hospitalization for heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P.C.; Ganda, A.; Lin, J.; Onat, D.; Harxhi, A.; Iyasere, J.E.; Uriel, N.; Cotter, G. Inflammatory activation: Cardiac, renal, and cardio-renal interactions in patients with the cardiorenal syndrome. Heart Fail. Rev. 2012, 17, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2012, 379, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.B.; Voloshyna, I.; De Leon, J.; Miyawaki, N.; Mattana, J. Cholesterol Metabolism in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massy, Z.A.; de Zeeuw, D. LDL cholesterol in CKD—To treat or not to treat? Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanktree, M.B.; Thériault, S.; Walsh, M.; Paré, G. HDL Cholesterol, LDL Cholesterol, and Triglycerides as Risk Factors for CKD: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoletti, E.; Zoccali, C. A look at the upper heart chamber: The left atrium in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.J.; Parfrey, P.S.; Foley, R.N. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in the Renal Patient. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001, 12, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Barberato, S.H. Left Ventricular Mass in Chronic Kidney Disease and ESRD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, S.; Shafiq, S.; Ali, S.; Ebad Ur Rehman, M.; Malik, J.; Lee, K.Y. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH) and Left Ventricular Geometric Patterns in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Stage 2–5 With Preserved Ejection Fraction (EF): A Systematic Review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuragi, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Yamada, K.; Tanimoto, M.; Miki, T.; Otsuka, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawamoto, K.; Katayama, Y.; Tanakaya, M.; et al. Serum cystatin C level is associated with left atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy and impaired left ventricular relaxation in patients with stage 2 or 3 chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 190, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, T.H.; Amann, K.; Bangalore, S.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Craig, J.C.; Gill, J.S.; Hlatky, M.A.; Jardine, A.G.; Landmesser, U.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and valvular heart disease: Conclusions from a KDIGO Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisinni, A.; Munafo, A.; Pivato, C.A.; Adamo, M.; Taramasso, M.; Scotti, A.; Parlati, A.L.; Italia, L.; Voci, D.; Buzzatti, N.; et al. Effect of Chronic Kidney Disease on 5-Year Outcome in Patients With Heart Failure and Secondary Mitral Regurgitation Undergoing Percutaneous MitraClip Insertion. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 171, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDIGO Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2020 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, S1–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelniker, T.A.; Braunwald, E. Cardiac and renal effects of sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in diabetes: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.-F.; Mann, J.F.E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lindberg, M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner–La Rocca, H.-P.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.S.; Hussain, M.S.; Roshan, M.H.K.; Pigazzani, F.; Choy, A.-M.; Khan, F.; Mordi, I.R.; Lang, C.C. Blood Urea/Creatinine Ratio and Mortality in Ambulatory Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Diseases 2025, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CKD Group n = 1641 | Non-CKD Group n = 586 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Population | |||

| Age, years | 72.70 ± 9.32 | 65.87 ± 11.00 | <0.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 629 (38.33%) | 146 (24.91%) | <0.001 |

| Antropometry | |||

| Body weight, kg | 81.22 ± 16.74 | 83.64 ± 17.65 | 0.004 |

| Body height, cm | 170.47 ± 8.66 | 172.57 ± 8.39 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.89 ± 5.15 | 28.02 ± 5.29 | 0.611 |

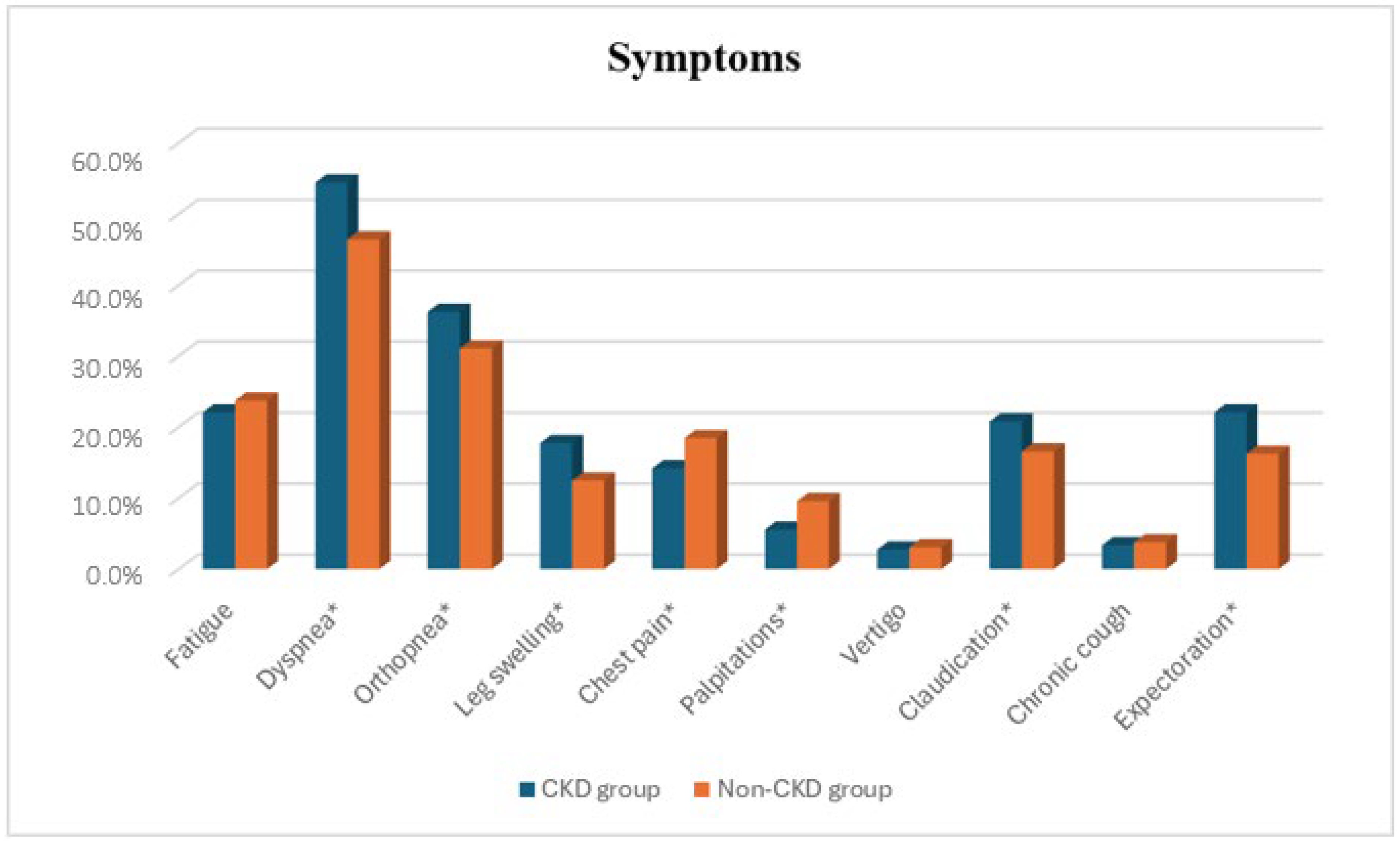

| Symptoms | |||

| Fatigue, n (%) | 362 (22.06%) | 139 (23.72%) | 0.409 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 893 (54.42%) | 272 (46.42%) | <0.001 |

| Orthopnea, n (%) | 594 (36.20%) | 182 (31.06%) | 0.025 |

| Leg swelling, n (%) | 291 (17.73%) | 73 (12.46%) | 0.003 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 233 (14.20%) | 108 (18.43%) | 0.015 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 91 (5.54%) | 56 (9.56%) | <0.001 |

| Vertigo, n (%) | 45 (2.74%) | 18 (3.07%) | 0.680 |

| Claudication, n (%) | 341 (20.78%) | 97 (16.55%) | 0.027 |

| Chronic cough, n (%) | 55 (3.35%) | 22 (3.75%) | 0.647 |

| Expectoration, n (%) | 362 (22.06%) | 95 (16.21%) | 0.003 |

| NYHA Classification | |||

| I, n (%) | 250 (15.57%) | 92 (16.23%) | <0.001 |

| II, n (%) | 55 (3.42%) | 59 (10.41%) | |

| III, n (%) | 239 (14.88%) | 112 (19.75%) | |

| IV, n (%) | 1062 (66.13%) | 304 (53.62%) | |

| Clinical Signs | |||

| Pulmonary crackles, n (%) | 998 (60.82%) | 304 (51.88%) | <0.001 |

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 304 (18.52%) | 73 (12.46%) | <0.001 |

| Mitral regurgitation murmur, n (%) | 619 (37.72%) | 145 (24.74%) | <0.001 |

| Carotid murmur, n (%) | 223 (13.59%) | 51 (8.70%) | 0.002 |

| Bilateral pretibial edema, n (%) | 291 (17.73%) | 73 (12.46%) | 0.003 |

| Tachypnea, n (%) | 35 (4.60%) | 6 (1.99%) | 0.046 |

| Vital Signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 129.55 ±32.07 | 133.54 ±29.30 | 0.011 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75.94 ± 17.46 | 79.36 ± 16.80 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats per minute | 91.24 ± 25.73 | 93.63 ± 26.52 | 0.065 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1148 (69.96%) | 436 (74.40%) | 0.042 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 803 (48.93%) | 262 (44.71%) | 0.079 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 628 (38.27%) | 228 (38.91%) | 0.785 |

| PCI, n (%) | 456 (27.79%) | 173 (29.52%) | 0.423 |

| CABG, n (%) | 245 (14.93%) | 78 (13.31%) | 0.339 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 1326 (80.80%) | 429 (73.21%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac valve surgery, n (%) | 194 (11.82%) | 47 (8.02%) | 0.011 |

| Other cardiac surgery, n (%) | 52 (3.17%) | 18 (3.07%) | 0.908 |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 14 (0.85%) | 5 (0.85%) | 1.000 |

| Acute rheumatic fever, n (%) | 24 (1.46%) | 7 (1.19%) | 0.635 |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 169 (10.30%) | 47 (8.02%) | 0.110 |

| ICD, n (%) | 38 (2.32%) | 16 (2.73%) | 0.575 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 234 (14.26%) | 75 (12.80%) | 0.380 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 636 (38.76%) | 213 (36.35%) | 0.303 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 564 (34.37%) | 292 (49.83%) | <0.001 |

| COPD/Asthma, n (%) | 325 (19.80%) | 104 (17.75%) | 0.278 |

| Heart Failure Type | |||

| HFrEF, n (%) | 782 (62.1%) | 315 (66.9%) | 0.114 |

| HFmrEF, n (%) | 169 (13.4%) | 62 (13.2%) | |

| HFpEF, n (%) | 309 (24.5%) | 94 (19.9%) | |

| In-hospital mortality | 468 (28.6%) | 65 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Parameters | CKD Group | Non-CKD Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose, mmol/L | 8.82 ± 4.62 | 8.50 ± 4.02 | 0.151 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 47.83 ± 65.59 | 34.88 ± 58.96 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 183.73 ± 118.93 | 83.54 ± 15.76 | <0.001 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 15.14 ± 8.98 | 7.91 ± 3.75 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, µmol/L | 487.93 ± 163.32 | 363.67 ± 121.57 | <0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 74.95 ± 209.87 | 51.96 ± 95.39 | 0.011 |

| ALT, U/L | 76.82 ± 213.75 | 47.02 ± 115.31 | 0.002 |

| GGT, U/L | 99.62 ± 110.26 | 81.51 ± 55.11 | 0.314 |

| Bilirubin, µmol/L | 19.79 ± 25.40 | 17.26 ± 19.39 | 0.033 |

| Total protein, g/L | 69.68 ± 10.20 | 70.33 ± 20.05 | 0.344 |

| Albumin, g/L | 32.72 ± 6.69 | 33.13 ± 7.12 | 0.586 |

| CK-MB, U/L | 35.70 ± 58.22 | 31.31 ± 35.95 | 0.089 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 1637.96 ± 6468.94 | 1419.22 ± 5654.90 | 0.569 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 12279.83 ± 9140.16 | 6882.81 ± 7022.54 | <0.001 |

| TSH, μIU/mL | 5,21 ± 7.96 | 3.08 ± 3.01 | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 120.66 ± 27.92 | 132.44 ± 24.10 | <0.001 |

| Red blood cells, 1012/L | 4.24 ± 0.78 | 4.55 ± 0.70 | <0.001 |

| MCV, fl | 89.62 ± 7.62 | 89.66 ± 7.39 | 0.929 |

| MCH, pg | 29.20 ± 2.92 | 29.62 ± 2.83 | 0.003 |

| MCHC, g/L | 287.16 ± 99.50 | 302.59 ± 87.55 | 0.001 |

| White blood cells, 109/L | 10.20 ± 5.10 | 9.48 ± 3.89 | 0.002 |

| Platelets, 109/L | 216.46 ± 85.96 | 224.04 ± 87.80 | 0.079 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 138.97 ± 6.20 | 138.96 ± 8.49 | 0.989 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 4.22 ± 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 1.23 ± 0.29 | 1.23 ± 0.22 | 0.928 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.59 ± 1.11 | 2.95 ± 1.48 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 0.98 ± 0.36 | 1.09 ± 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.13 ± 1.46 | 4.53 ± 1.59 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.47 ± 1.06 | 1.56 ± 1.14 | 0.224 |

| ECG Changes | CKD Group n = 1641 | Non-CKD Group n = 586 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinus rhythm, n (%) | 607 (36.99%) | 297 (50.68%) | <0.001 |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 169 (10.30%) | 47 (8.02%) | 0.110 |

| Atrial fibrilation, n (%) | 803 (48.93%) | 262 (44.71%) | 0.079 |

| Atrial flutter, n (%) | 20 (1.22%) | 9 (1.54%) | 0.561 |

| Other supraventricular arrhythmias, n (%) | 34 (2.07%) | 25 (4.27%) | 0.005 |

| LBBB, n (%) | 245 (14.93%) | 98 (16.72%) | 0.302 |

| LAFB, n (%) | 8 (0.49%) | 4 (0.68%) | 0.580 |

| ST elevation, n (%) | 29 (1.77%) | 22 (3.75%) | 0.006 |

| ST denivelation, n (%) | 172 (10.48%) | 69 (11.78%) | 0.387 |

| Inverted T waves, n (%) | 152 (9.26%) | 85 (14.50%) | <0.001 |

| ECHO Parameters | CKD Group | Non-CKD Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA, mm | 45.87 ± 14.04 | 45.39 ± 17.93 | 0.563 |

| LVIDD, mm | 56.63 ± 9.70 | 58.15 ± 9.41 | 0.004 |

| LVIDS, mm | 42.93 ± 11.97 | 44.32 ± 11.47 | 0.030 |

| IVS, mm | 11.93 ± 1.64 | 11.74 ± 1.69 | 0.036 |

| PLW, mm | 11.89 ± 3.21 | 11.65 ± 1.52 | 0.129 |

| LVEDV, mL | 146.39 ± 65.58 | 158.66 ± 70.78 | <0.001 |

| LVESV, mL | 98.79 ± 59.80 | 107.78 ± 64.46 | 0.006 |

| SVLV, mL | 47.65 ± 15.32 | 50.76 ± 15.16 | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 36.68 ± 13.85 | 35.91 ± 12.87 | 0.297 |

| E/e’ ratio | 18.23 ± 7.96 | 16.23 ± 8.08 | 0.005 |

| E V-max, m/s | 0.98 ± 0.38 | 0.92 ± 0.29 | 0.003 |

| A V-max, m/s | 0.89 ± 4.29 | 0.70 ± 0.27 | 0.545 |

| Mitral valve maxPG, mmHg | 6.73 ± 4.74 | 5.82 ± 4.08 | <0.001 |

| Mitral valve meanPG, mmHg | 2.71 ± 2.25 | 2.37 ± 1.94 | 0.010 |

| Mitral valve VTI, cm | 28.01 ± 12.80 | 25.93 ± 10.00 | 0.005 |

| MADd, mm | 35.21 ± 4.94 | 35.34 ± 4.40 | 0.774 |

| Mitral regurgitation | |||

| Absent, n (%) | 67 (5.41%) | 39 (8.30%) | <0.001 |

| Mild, n (%) | 563 (45.48%) | 240 (51.06%) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 427 (34.49%) | 160 (34.04%) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 181 (14.62%) | 31 (6.60%) | |

| RVSP, mmHg | 47.59 ± 13.31 | 42.98 ± 13.05 | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve maxPG, mmHg | 15.32 ± 16.42 | 12.89 ± 14.25 | 0.005 |

| Aortic valve meanPG, mmHg | 8.57 ± 10.02 | 7.28 ± 8.94 | 0.016 |

| Aortic valve VTI, cm | 35.11 ± 19.49 | 31.91 ± 16.10 | 0.002 |

| Aortic valve annulus, mm | 26.82 ± 4.75 | 26.48 ± 4.58 | 0.193 |

| Aortic valve leaflets separation, mm | 16.07 ± 6.35 | 17.13 ± 6.52 | 0.006 |

| Ascending aorta, mm | 35.26 ± 6.23 | 35.07 ± 4.59 | 0.626 |

| Medication | CKD Group | Non-CKD Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 1107 (67.5%) | 394 (67.2%) | 0.921 |

| ACEi/ARB/ARNI, n (%) | 1026 (62.5%) | 358 (61.1%) | 0.540 |

| MRA, n (%) | 728 (44.4%) | 250 (42.7%) | 0.476 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, n (%) * | 180 (20.6%) | 131 (35.2%) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 1133 (69.0%) | 403 (68.8%) | 0.903 |

| CCB, n (%) | 56 (3.4%) | 16 (2.7%) | 0.423 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 221 (13.5%) | 86 (14.7%) | 0.466 |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 155 (9.4%) | 57 (9.7%) | 0.842 |

| Anticoagulants, n (%) | 642 (39.1%) | 247 (42.1%) | 0.199 |

| Antiplatelets, n (%) | 780 (47.5%) | 251 (42.8%) | 0.050 |

| Statins, n (%) | 643 (39.2%) | 212 (36.2%) | 0.199 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ilić, A.; Kovačević, O.; Milovančev, A.; Mladenović, N.; Andrić, D.; Dabović, D.; Jaraković, M.; Maletin, S.; Pantić, T.; Crnomarković, B.; et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Features in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Diseases 2026, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010035

Ilić A, Kovačević O, Milovančev A, Mladenović N, Andrić D, Dabović D, Jaraković M, Maletin S, Pantić T, Crnomarković B, et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Features in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Diseases. 2026; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlić, Anastasija, Olivera Kovačević, Aleksandra Milovančev, Nikola Mladenović, Dragica Andrić, Dragana Dabović, Milana Jaraković, Srdjan Maletin, Teodora Pantić, Branislav Crnomarković, and et al. 2026. "Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Features in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure" Diseases 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010035

APA StyleIlić, A., Kovačević, O., Milovančev, A., Mladenović, N., Andrić, D., Dabović, D., Jaraković, M., Maletin, S., Pantić, T., Crnomarković, B., Preveden, M., Zdravković, R., Stojšić Milosavljević, A., Ilić, A., Velicki, L., & Preveden, A. (2026). Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Features in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Diseases, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010035