Survival Prediction in Septic ICU Patients: Integrating Lactate and Vasopressor Use with Established Severity Scores

Abstract

1. Introduction

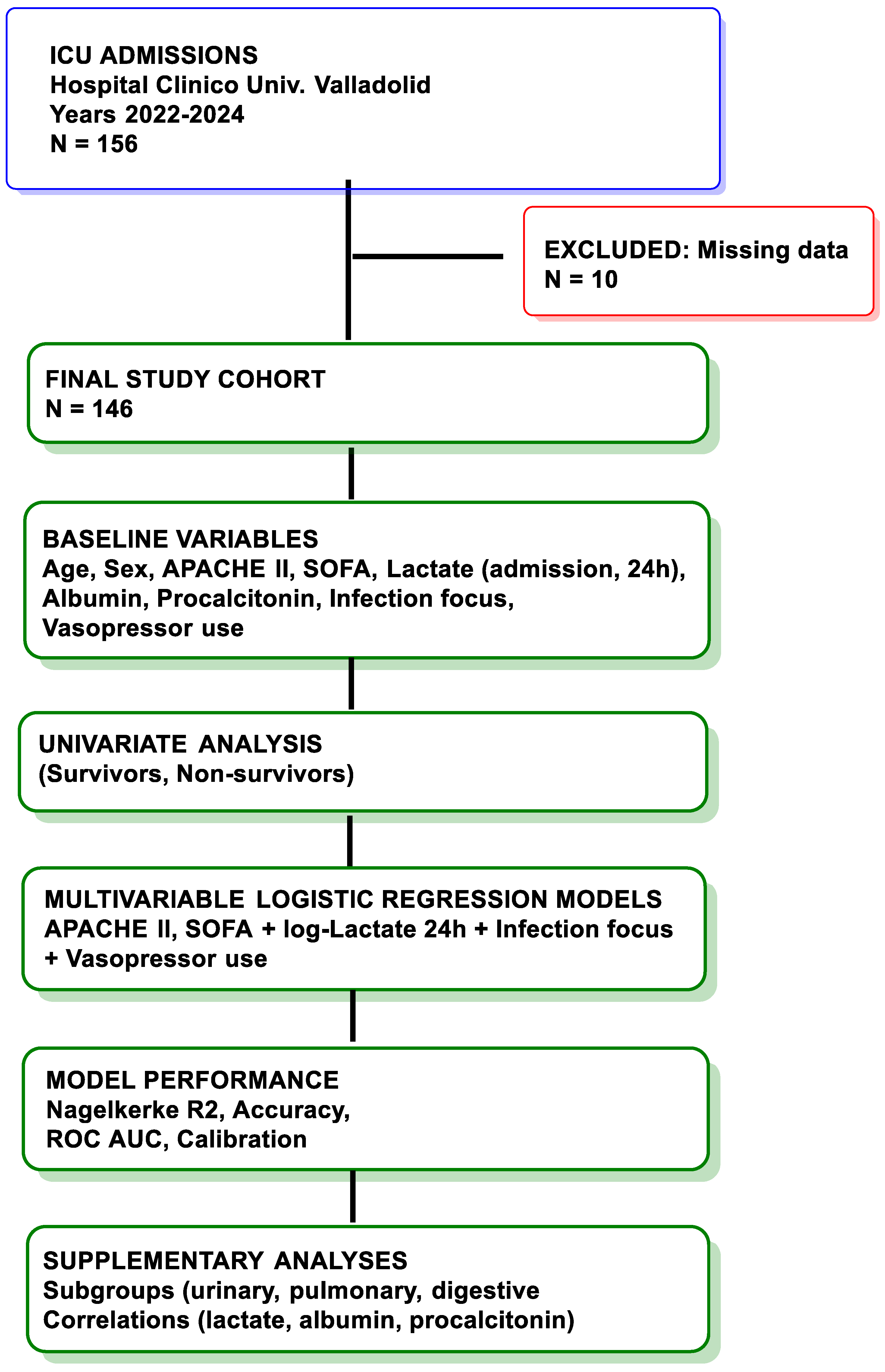

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objective

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Patient Population

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Univariable Predictors

3.3. Correlations Between Biomarkers

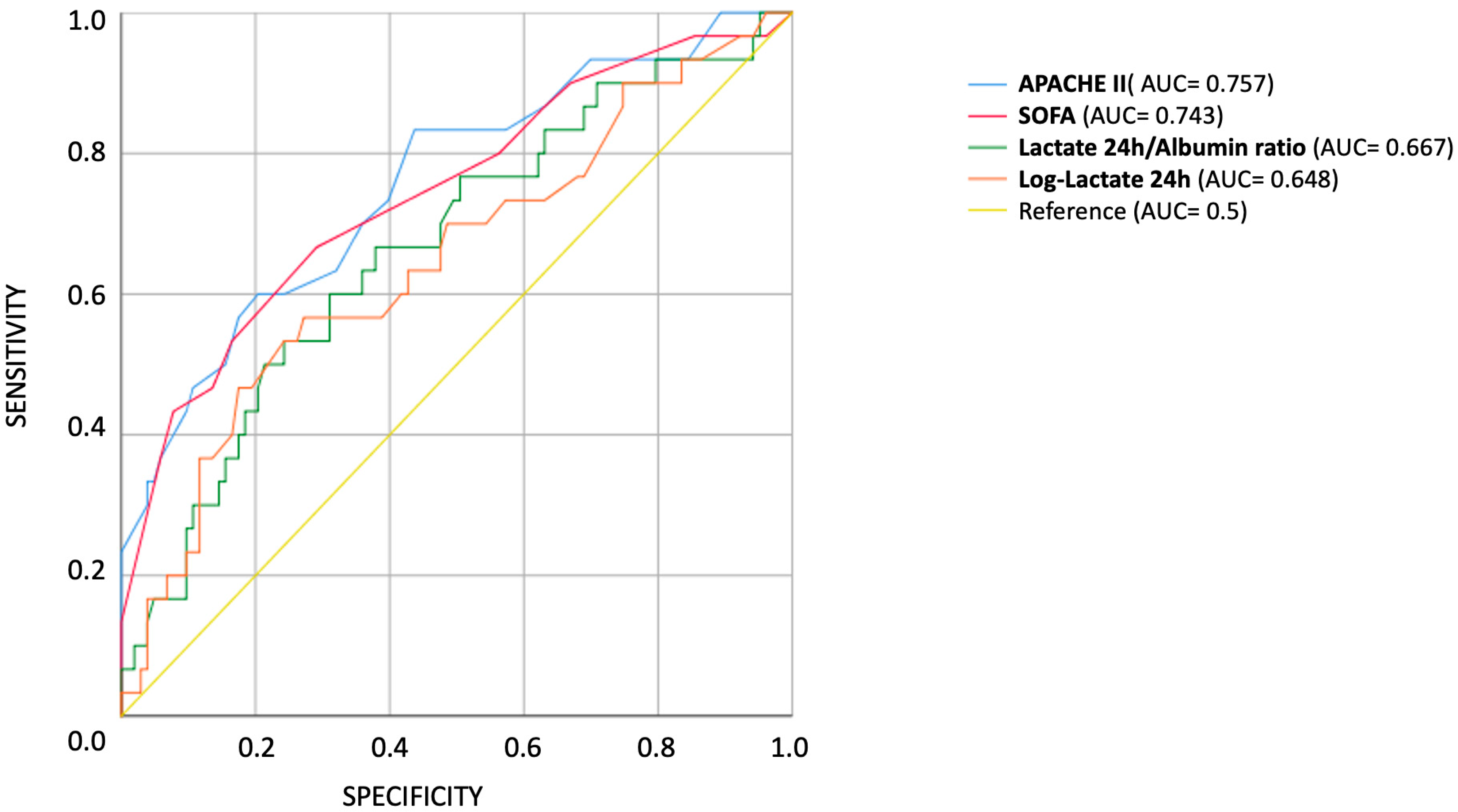

3.4. Multivariable Logistic Regression Models

4. Discussion

5. Clinical Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ros, M.M.; van der Zaag-Loonen, H.J.; Hofhuis, J.G.; Spronk, P.E. Survival prediction in severely ill patients study—The prediction of survival in critically ill patients by ICU physicians. Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, e0317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, N.; Varon, J. Fostering trust in critical care medicine: A comprehensive analysis of patient-provider relationships. Crit. Care Shock 2023, 26, 303. [Google Scholar]

- Cipulli, F.; Balzani, E.; Marini, G.; Lassola, S.; De Rosa, S.; Bellani, G. ICU ‘Magic Numbers’: The Role of Biomarkers in Supporting Clinical Decision-Making. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorooshi, G.; Samsamshariat, S.; Gheshlaghi, F.; Zoofaghari, S.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Abbasi, S.; Eizadi-Mood, N. Comparing sequential organ failure assessment score, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, modified acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, simplified acute physiology score II and poisoning severity score for outcome prediction of pesticide poisoned patients admitted to the intensive care unit. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 12, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, R.; Rehan, M.; Banerjee, S.; Gadre, S.; Paul, P.; Gupta, S. The Utility of SOFA Score and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) Score in Analysing Patients with Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome and Sepsis. Int. J. Med. All Body Health Res. 2022, 3, 18–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.T.; Knaus, W.A. Predicting outcome in critical care: The current status of the APACHE prognostic scoring system. Can. J. Anaesth. 1991, 38, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Diao, X.; Chen, H.; Cai, K.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. Dynamic APACHE II score to predict the outcome of intensive care unit patients. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 744907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, R.; Vincent, J.-L.; Matos, R.; Mendonca, A.; Cantraine, F.; Thijs, L.; Takala, J.; Sprung, C.; Antonelli, M.; Bruining, H. The use of maximum SOFA score to quantify organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care. Results of a prospective, multicentre study. Intensive Care Med. 1999, 25, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Safford, M.M.; Shapiro, N.I.; Baddley, J.W.; Wang, H.E. Application of the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis (Sepsis-3) Classification: A retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirey, T.L. POC lactate: A marker for diagnosis, prognosis, and guiding therapy in the critically ill. Point Care 2007, 6, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.; Nijsten, M.W.; Jansen, T.C. Clinical use of lactate monitoring in critically ill patients. Ann. Intensive Care 2013, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 10Jansen, T.C.; van Bommel, J.; Schoonderbeek, F.J.; Sleeswijk Visser, S.J.; van der Klooster, J.M.; Lima, A.P.; Willemsen, S.P.; Bakker, J. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Damiani, L.P.; Estenssoro, E.; Dubin, A.; Hurtado, J.; Friedman, G.; Castro, R.; Alegría, L.; Teboul, J.L.; et al. Effect of a Resuscitation Strategy Targeting Peripheral Perfusion Status vs. Serum Lactate Levels on 28-Day Mortality Among Patients With Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, O.; Grunnet, N.; Barfod, C. Blood lactate as a predictor for in-hospital mortality in patients admitted acutely to hospital: A systematic review. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2011, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Dubois, M.J.; Navickis, R.J.; Wilkes, M.M. Hypoalbuminemia in acute illness: Is there a rationale for intervention? A meta-analysis of cohort studies and controlled trials. Ann. Surg. 2003, 237, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Liu, C.; Lang, M.; Yao, F. Prognostic value of the lactate-to-albumin ratio in critically ill chronic heart failure patients with sepsis: Insights from a retrospective cohort study. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1593524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Jo, I.J.; Kim, W.Y.; Ryoo, S.M.; Kang, G.H.; Kim, K.; Jo, Y.H.; Chung, S.P.; Joo, Y.S.; et al. Prognostic Value of The Lactate/Albumin Ratio for Predicting 28-Day Mortality in Critically ILL Sepsis Patients. Shock 2018, 50, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Birkhahn, R.; Sherwin, R.; Jones, A.E.; Singer, A.; Kline, J.A.; Runyon, M.S.; Self, W.H.; Courtney, D.M.; Nowak, R.M.; et al. Serial Procalcitonin Predicts Mortality in Severe Sepsis Patients: Results From the Multicenter Procalcitonin MOnitoring SEpsis (MOSES) Study. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Su, L.; Han, G.; Yan, P.; Xie, L. Prognostic Value of Procalcitonin in Adult Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorr, A.F.; Tabak, Y.P.; Killian, A.D.; Gupta, V.; Liu, L.Z.; Kollef, M.H. Healthcare-associated bloodstream infection: A distinct entity? Insights from a large U.S. database. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 2588–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.; Gibot, S.; Franck, P.; Cravoisy, A.; Bollaert, P.E. Relation between muscle Na+K+ ATPase activity and raised lactate concentrations in septic shock: A prospective study. Lancet 2005, 365, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez, M.; Marik, P.; Bellomo, R. Sepsis-associated hyperlactatemia. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H. Association between lactate to albumin ratio and mortality among sepsis associated acute kidney injury patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P.; Pramesh, C.S.; Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Logistic regression. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2017, 8, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaus, W.A.; Draper, E.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Zimmerman, J.E. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 1985, 13, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Moreno, R.; Takala, J.; Willatts, S.; De Mendonça, A.; Bruining, H.; Reinhart, C.K.; Suter, P.M.; Thijs, L.G. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996, 22, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, D.; Biston, P.; Devriendt, J.; Madl, C.; Chochrad, D.; Aldecoa, C.; Brasseur, A.; Defrance, P.; Gottignies, P.; Vincent, J.L. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dünser, M.W.; Ruokonen, E.; Pettilä, V.; Ulmer, H.; Torgersen, C.; Schmittinger, C.A.; Jakob, S.; Takala, J. Association of arterial blood pressure and vasopressor load with septic shock mortality: A post hoc analysis of a multicenter trial. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, J.E.; Kramer, A.A.; McNair, D.S.; Malila, F.M. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: Hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Endoh, H.; Kamimura, N.; Tamakawa, T.; Nitta, M. Lactate indices as predictors of in-hospital mortality or 90-day survival after admission to an intensive care unit in unselected critically ill patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.; Oh, D.K.; Park, M.H.; Lim, C.-M.; Lee, S.-M.; Lee, H.Y.; Investigators, K.S.A. Serial evaluation of the serum lactate level with the SOFA score to predict mortality in patients with sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Qin, C.; Shi, R.; Huang, Y.; Gong, J.; Zeng, X.; Wang, D. Lactate-to-albumin ratio as a potential prognostic predictor in patients with cirrhosis and sepsis: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, I.; Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Panagopoulos, F.; Tsilingiris, D.; Dalamaga, M. Kinetics of the Lactate to Albumin Ratio in New Onset Sepsis: Prognostic Implications. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Bench-to-bedside review: Vasopressin in the management of septic shock. Crit. Care 2011, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Jentzer, J.C.; Kotecha, A.A.; Murphree, D.H., Jr.; Barreto, E.F.; Khanna, A.K.; Iyer, V.N. Development and performance of a novel vasopressor-driven mortality prediction model in septic shock. Ann. Intensive Care 2018, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yao, L. The predictive value of the lactate/albumin ratio combined with APACHE II and injury severity score for short-term prognosis in patients with polytrauma. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenauer, M.; Wernly, B.; Ohnewein, B.; Franz, M.; Kabisch, B.; Muessig, J.; Masyuk, M.; Lauten, A.; Schulze, P.C.; Hoppe, U.C.; et al. The Lactate/Albumin Ratio: A Valuable Tool for Risk Stratification in Septic Patients Admitted to ICU. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Chebl, R.; Jamali, S.; Sabra, M.; Safa, R.; Berbari, I.; Shami, A.; Makki, M.; Tamim, H.; Abou Dagher, G. Lactate/Albumin Ratio as a Predictor of In-Hospital Mortality in Septic Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 550182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Takayama, W.; Murata, K.; Otomo, Y. The impact of lactate clearance on outcomes according to infection sites in patients with sepsis: A retrospective observational study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | ICU Survivors (n = 112) | ICU Non-Survivors (n = 34) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 71.0 ± 11.7 | 66.9 ± 13.4 | 0.103 |

| Sex, male (%) | 50.0% | 59.0% | 0.340 |

| APACHE II (mean ± SD) | 19.9 ± 7.1 | 29.1 ± 10.6 | <0.001 |

| SOFA score (median [IQR]) | 6 [5] | 9 [6] | <0.001 |

| Lactate at admission * (mmol/L, median [IQR]) | 1.6 [1.2] | 2.4 [2.7] | 0.020 * |

| Lactate at 24 h (mmol/L, median [IQR]) | 1.53 [1.10] | 2.25 [2.51] | 0.002 |

| Log-lactate at 24 h (mean ± SD) | 0.48 ± 0.53 | 0.94 ± 0.85 | 0.004 |

| Albumin (g/dL, mean ± SD) | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 0.280 |

| Procalcitonin 24 h median [IQR]) | 4.51 [21.86] | 6.64 [17.58] | 0.58 |

| LogProcalcitonin 24 h (mean ± SD) | 1.34 ± 2.34 | 1.52 ± 1.83 | 0.68 |

| Infection focus, urinary (%) | 30.0% | 12.0% | 0.035 |

| Vasopressor use, any (%) | 41.0% | 82.0% | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor category, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 32 (28.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 65 (58.0%) | 22 (64.7%) | |

| 5 (4.5%) | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 4 (3.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 6 (5.4%) | 6 (17.6%) |

| Model | Predictors Included | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Nagelkerke R2 | Correct Classification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | APACHE II | 1.106 (1.04–1.17) | 0.001 | 0.324 | 84.5 |

| SOFA | 1.185 (1.03–1.36) | 0.020 | |||

| B | APACHE II | 1.092 (1.03–1.16) | 0.004 | 0.348 | 84.9 |

| SOFA | 1.185 (1.02–1.38) | 0.023 | |||

| log-lactate (24 h) | 1.920 (0.95–3.87) | 0.066 | |||

| C | APACHE II | 1.097 (1.03–1.17) | 0.004 | 0.329 | 85.0 |

| SOFA | 1.173 (1.01–1.36) | 0.040 | |||

| LAR (lactate/albumin) | 1.411 (0.82–2.43) | 0.212 | |||

| D | APACHE II | 1.086 (1.02–1.16) | 0.008 | 0.395 | 85.6 |

| SOFA | 1.176 (1.01–1.37) | 0.033 | |||

| log-lactate (24 h) | 1.952 (0.96–3.99) | 0.067 | |||

| Infection focus (urinary) | 0.188 (0.04–0.88) | 0.035 | |||

| E | APACHE II | 1.089 (1.02–1.16) | 0.010 | 0.448 | 89.6 |

| SOFA | 1.199 (1.01–1.42) | 0.037 | |||

| log-lactate (24 h) | 1.469 (0.62–3.48) | 0.380 | |||

| Vasopressor category (ref = none) | — | >0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andrés, C.M.C.; Rodriguez del Tio, M.d.P.; Bueno Gonzalez, A.M.; Artola Blanco, M.; Medina Díez, S.; Francisco Amador, A.; Munguira, E.B.; Lastra, J.M.P.d.l. Survival Prediction in Septic ICU Patients: Integrating Lactate and Vasopressor Use with Established Severity Scores. Diseases 2026, 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010011

Andrés CMC, Rodriguez del Tio MdP, Bueno Gonzalez AM, Artola Blanco M, Medina Díez S, Francisco Amador A, Munguira EB, Lastra JMPdl. Survival Prediction in Septic ICU Patients: Integrating Lactate and Vasopressor Use with Established Severity Scores. Diseases. 2026; 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrés, Celia María Curieses, Maria del Pilar Rodriguez del Tio, Ana María Bueno Gonzalez, Mercedes Artola Blanco, Silvia Medina Díez, Amanda Francisco Amador, Elena Bustamante Munguira, and José M. Pérez de la Lastra. 2026. "Survival Prediction in Septic ICU Patients: Integrating Lactate and Vasopressor Use with Established Severity Scores" Diseases 14, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010011

APA StyleAndrés, C. M. C., Rodriguez del Tio, M. d. P., Bueno Gonzalez, A. M., Artola Blanco, M., Medina Díez, S., Francisco Amador, A., Munguira, E. B., & Lastra, J. M. P. d. l. (2026). Survival Prediction in Septic ICU Patients: Integrating Lactate and Vasopressor Use with Established Severity Scores. Diseases, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010011