Impact of Race on Admission, Clinical Outcomes, and Disposition in Cholangiocarcinoma: Insights from the National Inpatient Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Database—The National Inpatient Sample 2022

2.2. Study Population and Study Variable

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient- and Hospital-Level Characteristics

3.2. Primary Outcomes

3.3. In-Hospital Complications

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tyson, G.L.; El-Serag, H.B. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2011, 54, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauterio, A.; De Carlis, R.; Centonze, L.; Buscemi, V.; Incarbone, N.; Vella, I.; De Carlis, L. Current surgical management of peri-hilar and intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaib, Y.; El-Serag, H.B. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 2004, 24, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, T.D.; Momin, B.; Wilson, R.J.; Henley, S.J.; Wu, M.; Ryerson, A.B. Incidence and mortality of cancers of the biliary tract, gallbladder, and liver by sex, age, race/ethnicity, and stage at diagnosis: United States, 2013 to 2017. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2021, 30, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Konyn, P.; Cholankeril, G.; Bonham, C.A.; Ahmed, A. Trends in the mortality of biliary tract cancers based on their anatomical site in the United States from 2009 to 2018. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javle, M.; Lee, S.; Azad, N.S.; Borad, M.J.; Kelley, R.K.; Sivaraman, S.; Teschemaker, A.; Chopra, I.; Janjan, N.; Parasuraman, S.; et al. Temporal changes in cholangiocarcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States from 2001 to 2017. Oncologist 2022, 27, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio, P.; Malvezzi, M.; Carioli, G.; Hashim, D.; Boffetta, P.; El-Serag, H.B.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E. Global trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghi, S.; Liu, B.; Bhuket, T.; Wong, R.J. Sex-specific and race/ethnicity-specific disparities in cholangiocarcinoma incidence and prevalence in the USA: An updated analysis of the 2000–2011 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registry. Hepatol. Res. 2016, 46, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.M.; Liu, Y.; Gamboa, A.C.; Zaidi, M.Y.; Kooby, D.A.; Shah, M.M.; Cardona, K.; Russell, M.C.; Maithel, S.K. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors in cholangiocarcinoma: What is driving disparities in receipt of treatment? J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 120, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.N.; Kröner, P.T.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Corral, J.E.; Harnois, D.M.; Lukens, F.J. Increased odds of cholangiocarcinoma in Hispanics: Results of a nationwide analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 32, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, T.; Xu, L.; Luan, X. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cholangiocarcinoma: An updated meta-analysis. Gastroenterol. Rev. 2015, 10, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.S.; Han, T.-J.; Jing, N.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.-H.; Ma, F.-Z.; Liu, J.-Y. Obesity and the risk of cholangiocarcinoma: A meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 6831–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrick, J.L.; Yang, B.; Altekruse, S.F.; Van Dyke, A.L.; Koshiol, J.; Graubard, B.I.; McGlynn, K.A. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A population-based study in SEER-Medicare. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groen, P.C.; Gores, G.J.; LaRusso, N.F.; Gunderson, L.L.; Nagorney, D.M. Biliary tract cancers. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2022. Available online: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NISIntroduction2020.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- HCUP Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) for ICD-10-CM Diagnoses, v2021.2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2021. Available online: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/dxccsr.jsp (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Baidoun, F.; Sarmini, M.T.; Merjaneh, Z.; Moustafa, M.A. Controversial risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, O.F.; Kaufman, R.; Greten, T.F.; Monge, C. Disparities in cholangiocarcinoma research and trials: Challenges and opportunities in the United States. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2025, 11, e2400537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.J.; Jabbour, S.; Parekh, N.; Lin, Y.; Moss, R.A. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: An analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharia, A.; Mahayni, A.A.; Borra, R.; Peshin, S.; Ser-Manukyan, H.; Mangu, S.; Patel, D.M.; Muddassir, S. Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cancer-free and all-cause survival in cholangiocarcinoma patients under 60: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, S.O.; Mousa, O.Y.; Patel, T. Racial, ethnic, and age disparities in incidence and survival of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States; 1995–2014. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.; Ibodeng, G.-O.; Guarin, G.; Dourado, C.M. Racial disparities in hospitalization outcomes among patients with cholangiocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.M.; Woldesenbet, S.; Endo, Y.; Lima, H.A.; Alaimo, L.; Moazzam, Z.; Shaikh, C.; Cloyd, J.; Ejaz, A.; Azap, R.; et al. Racial segregation among patients with cholangiocarcinoma-impact on diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Ye, X. The benefits of an offline to online cognitive behavioral stress management regarding anxiety, depression, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in postoperative intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Eguchi, M.; Min, S.J.; Fischer, S. Outcomes of patients with cancer discharged to a skilled nursing facility after acute care hospitalization. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, V.; Jobanputra, Y.; Thota, P.N.; Menon, K.V.; Parsi, M.A.; Sanaka, M.R. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- HCUP Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) Chronic Condition Indicator for ICD-10-CM Diagnoses, v2021.21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2021. Available online: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Kumar, A.; Soares, H.P.; Balducci, L.; Djulbegovic, B. Treatment tolerance and outcomes in older adults with cancer: A systematic review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1210–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mojtahedi, Z.; Yoo, J.W.; Callahan, K.; Bhandari, N.; Lou, D.; Ghodsi, K.; Shen, J.J. Inpatient palliative care is less utilized in rare, fatal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A ten-year national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransome, E.; Tong, L.; Espinosa, J.; Chou, J.; Somnay, V.; Munene, G. Trends in surgery and disparities in receipt of surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the US: 2005–2014. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | White [4936] (%) | African American [758] (%) | Hispanic [993] (%) | Asian or Pacific Islander [507] (%) | Native American [47] (%) | Other [238] (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| Mean age (years) | 69 | 66 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 64 | |

| Age <= 64 years | 30.71 | 43.13 | 43.90 | 35.50 | 34.04 | 46.63 | <0.001 |

| Age >= 65 years | 69.28 | 56.86 | 46.09 | 64.49 | 65.95 | 53.36 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male (%) | 54.32 | 50.40 | 48.44 | 59.37 | 59.57 | 57.14 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 45.68 | 49.60 | 51.56 | 40.63 | 40.43 | 42.86 | |

| Median household income national quartiles | |||||||

| Quartile 1 (0–25th percentile) * | 19.08 | 43.11 | 31.73 | 7.20 | 47.73 | 17.09 | <0.001 |

| Quartile 2 (26–50th percentile) ** | 24.14 | 21.29 | 20.88 | 19.60 | 11.36 | 17.09 | |

| Quartile 3 (51st–75th percentile) *** | 26.86 | 21.02 | 27.94 | 27.40 | 29.55 | 27.78 | |

| Quartile 4 (76th–100th percentile) **** | 29.91 | 14.59 | 19.45 | 45.80 | 11.36 | 38.03 | |

| Insurance type | |||||||

| Medicare | 66.65 | 55.92 | 51.87 | 54.93 | 65.22 | 45.02 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 5.41 | 13.20 | 21.99 | 14.69 | 8.70 | 22.08 | |

| Private, including Health Maintenance Organization | 26.86 | 28.16 | 22.10 | 28.37 | 26.09 | 30.30 | |

| Self-pay | 1.08 | 2.72 | 4.05 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 2.60 | |

| Hospital region | |||||||

| Northeast | 23.26 | 17.15 | 15.91 | 18.74 | 2.13 | 31.09 | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 25.83 | 18.47 | 9.26 | 10.65 | 23.40 | 12.61 | |

| South | 33.35 | 57.26 | 35.65 | 18.15 | 34.04 | 30.67 | |

| West | 17.56 | 7.12 | 39.17 | 52.47 | 40.43 | 25.63 | |

| Teaching status | |||||||

| Non-teaching | 16.47 | 11.61 | 9.97 | 14.20 | 21.28 | 14.29 | <0.001 |

| Teaching | 83.53 | 88.39 | 90.03 | 85.80 | 78.72 | 85.71 | |

| Hospital bed size | |||||||

| Small | 15.82 | 15.44 | 11.38 | 10.06 | 25.53 | 11.76 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 24.82 | 21.64 | 23.36 | 23.67 | 23.40 | 21.01 | |

| Large | 59.36 | 62.93 | 65.26 | 66.27 | 51.06 | 67.23 | |

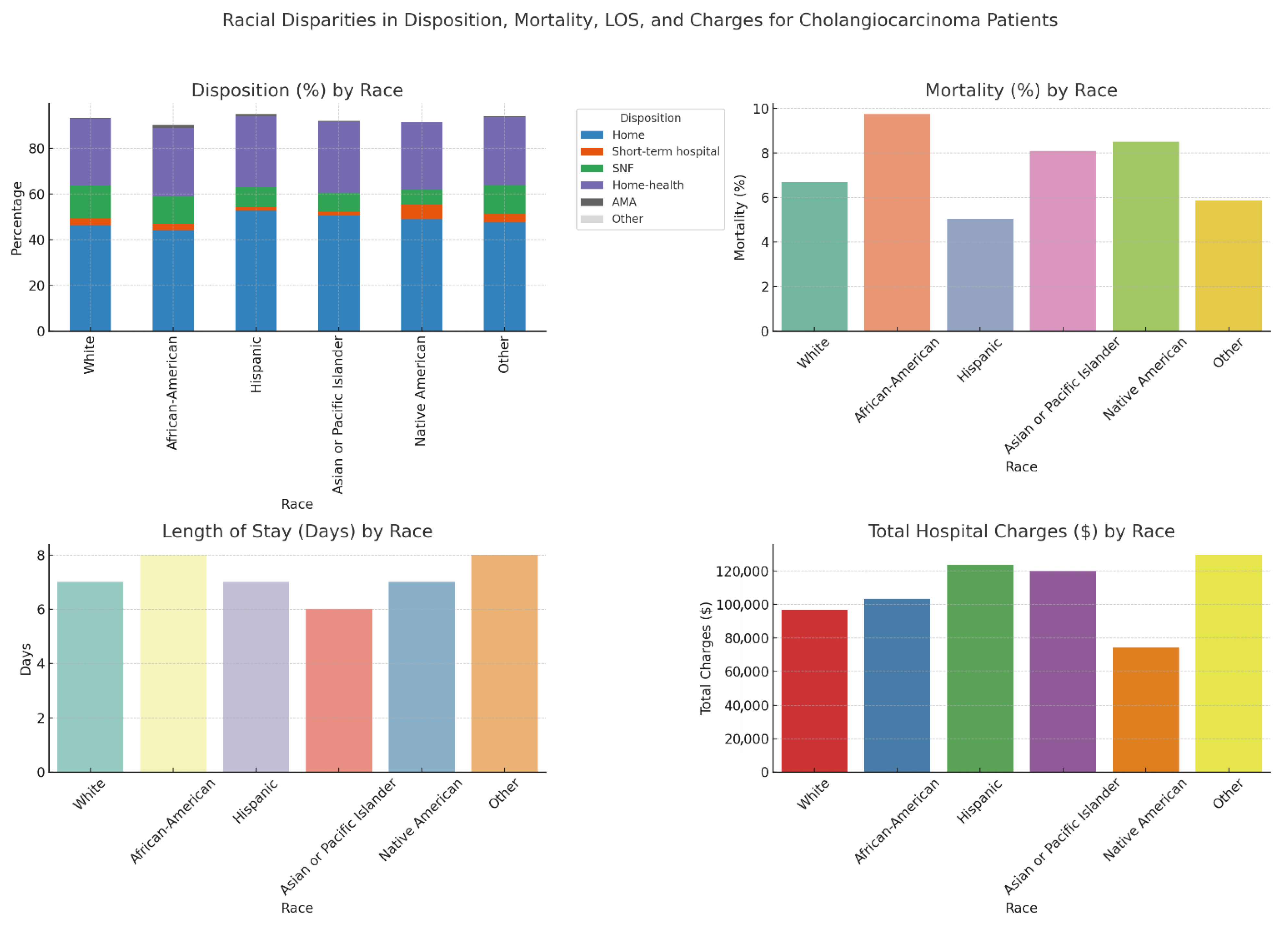

| Outcomes | White [4936] (%) | African American [758] (%) | Hispanic [993] (%) | Asian or Pacific Islander [507] (%) | Native American [47] (%) | Other [238] (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Disposition | |||||||

| Home | 46.25 | 44.06 | 52.67 | 50.49 | 48.94 | 47.48 | <0.001 |

| Short-Term Hospital | 3.06 | 2.77 | 1.51 | 1.78 | 6.38 | 3.78 | |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 14.28 | 12.14 | 8.76 | 8.09 | 6.36 | 12.61 | |

| Home Health | 29.19 | 29.82 | 31.12 | 31.16 | 29.79 | 29.83 | |

| Against Medical Advice | 0.47 | 1.45 | 0.91 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.42 | |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Mortality | 6.69 | 9.76 | 5.04 | 8.09 | 8.51 | 5.88 | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Total Charge (USD) | 96,596 | 103,490 | 123,703 | 119,909 | 74,064 | 129,606 | <0.00 |

| Elective vs. Non-Elective Admission AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Mortality AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | |

|---|---|---|

| White [4936] | Reference | Reference |

| African American [758] | 0.70 (0.54–0.89, 0.004) | 1.44 (1.10–1.90, 0.007) |

| Hispanic [993] | 0.62 (0.50–0.77, 0.00) | 0.70 (0.51–0.96, 0.02) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander [507] | 0.67 (0.51–0.89, 0.00) | 1.2 (0.85–1.7, 0.28) |

| Native American [47] | 1.16 (0.53–2.54, 0.38) | 1.4 (0.47–1.47, 0.53) |

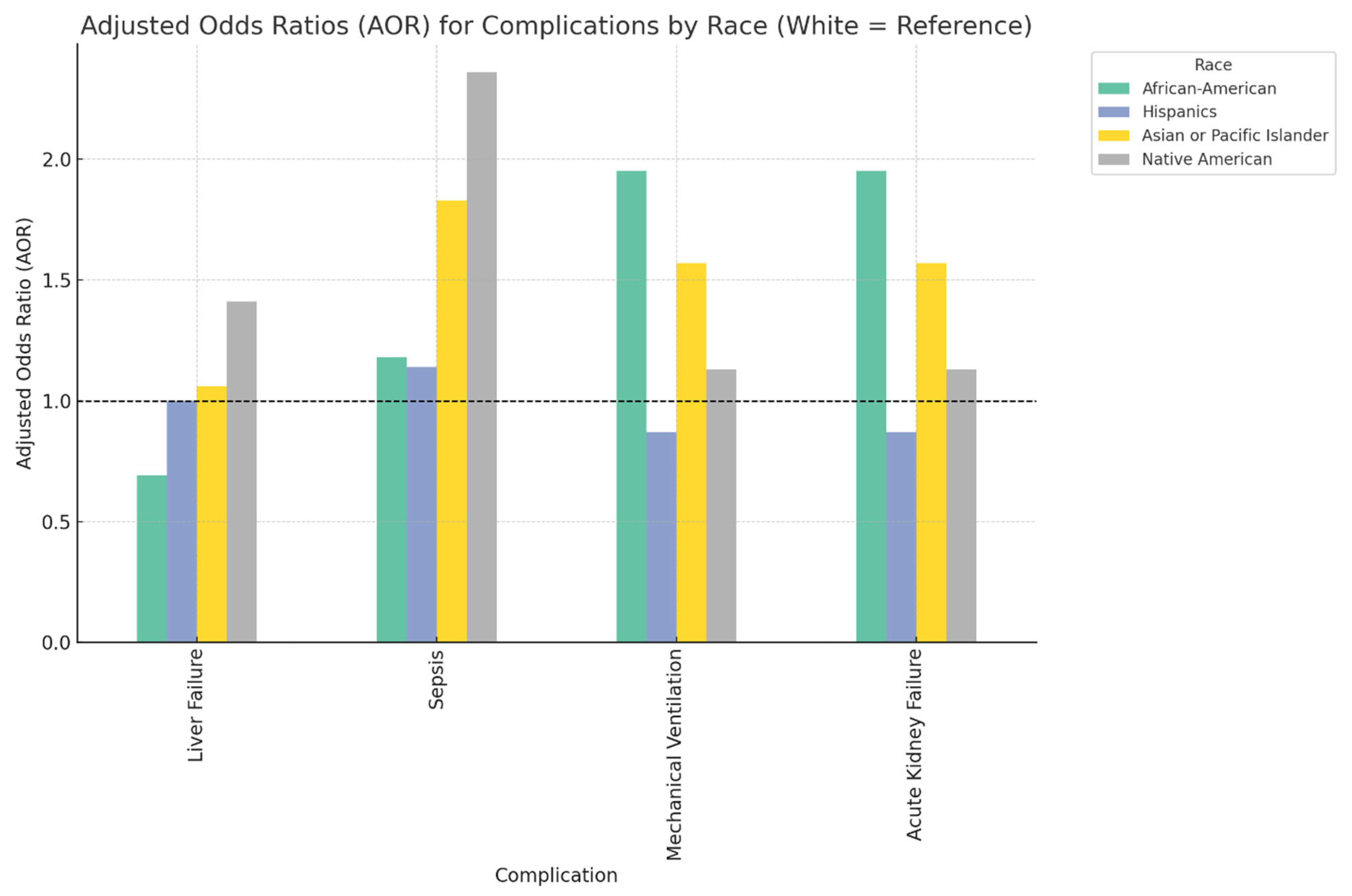

| Complications | White | African American AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Hispanics AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Asian or Pacific Islander AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Native American AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Failure | Reference | 0.69 (0.49–0.97, 0.03) | 1.00 (0.76–1.32, 0.96) | 1.06 (0.73–1.53, 0.33) | 1.41 (0.89–1.53, 0.74) |

| Sepsis | Reference | 1.18 (0.92–1.51, 0.16) | 1.14 (0.91–1.43, 0.23) | 1.83 (1.41–2.36, 0.00) | 2.36 (1.12–2.56, 0.02) |

| Mechanical Ventilation | Reference | 1.95 (1.3–2.92, 0.0010) | 0.87 (0.74–1.4, 0.59) | 1.57 (0.92–1.72, 0.07) | 1.13 (0.87–1.36, 0.13) |

| Acute Kidney Failure | Reference | 1.95 (1.30–2.92, 0.00) | 0.87 (0.59–1.40, 0.59) | 1.57 (0.95–1.42, 0.07) | 1.13 (0.96–1.43, 0.89) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathew, T.A.; Varghese, T.M.; Krishnakumaran, N.; Varghese, G.M.; Haq, K.S.; Khosla, A.; Jacob, R.; Vaccaro, G. Impact of Race on Admission, Clinical Outcomes, and Disposition in Cholangiocarcinoma: Insights from the National Inpatient Database. Diseases 2025, 13, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13070211

Mathew TA, Varghese TM, Krishnakumaran N, Varghese GM, Haq KS, Khosla A, Jacob R, Vaccaro G. Impact of Race on Admission, Clinical Outcomes, and Disposition in Cholangiocarcinoma: Insights from the National Inpatient Database. Diseases. 2025; 13(7):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13070211

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathew, Tijin A., Teresa M. Varghese, Nithya Krishnakumaran, George M. Varghese, Khwaja S. Haq, Akshita Khosla, Rojymon Jacob, and Gina Vaccaro. 2025. "Impact of Race on Admission, Clinical Outcomes, and Disposition in Cholangiocarcinoma: Insights from the National Inpatient Database" Diseases 13, no. 7: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13070211

APA StyleMathew, T. A., Varghese, T. M., Krishnakumaran, N., Varghese, G. M., Haq, K. S., Khosla, A., Jacob, R., & Vaccaro, G. (2025). Impact of Race on Admission, Clinical Outcomes, and Disposition in Cholangiocarcinoma: Insights from the National Inpatient Database. Diseases, 13(7), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13070211