Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing the Symptoms of Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

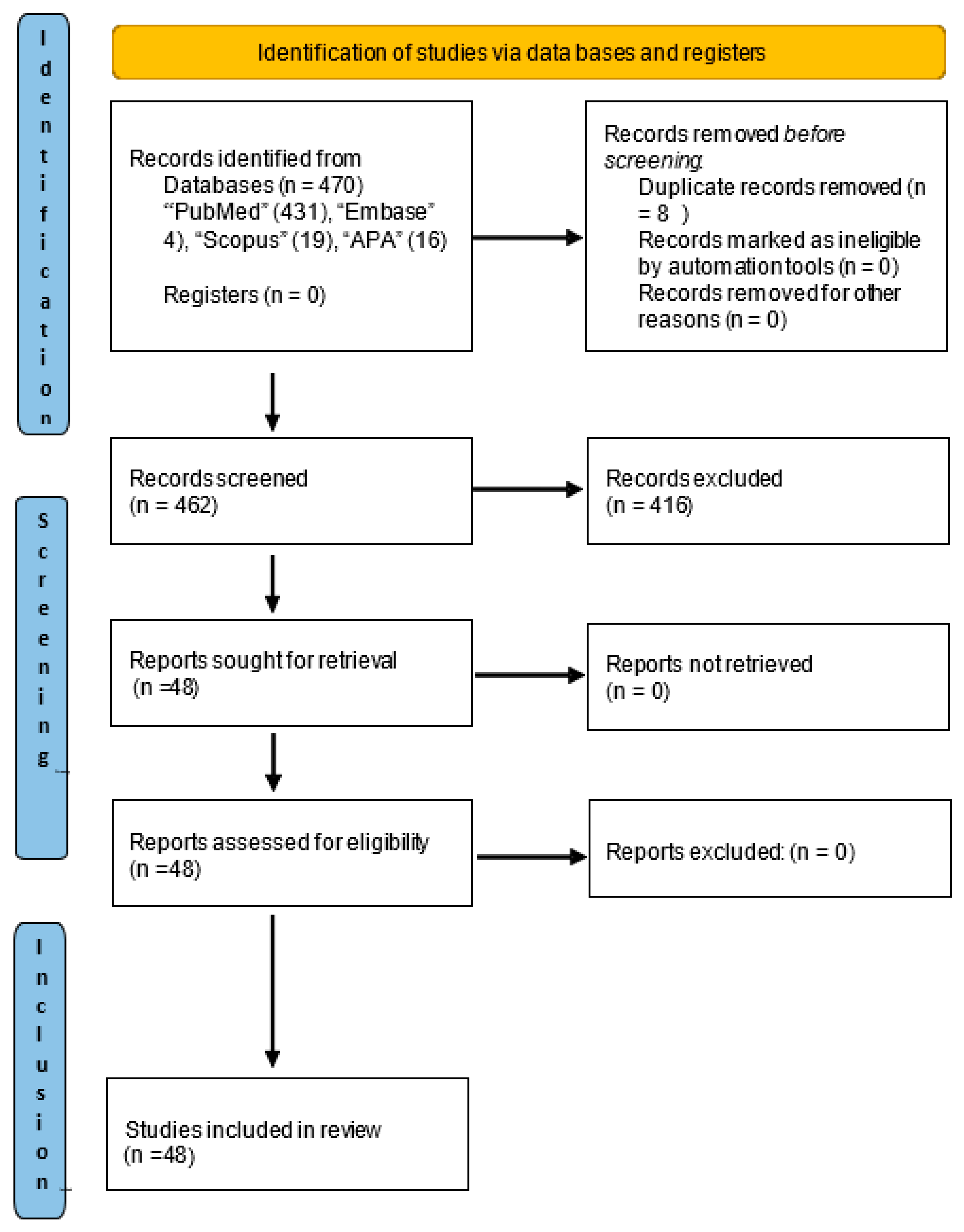

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Analysis of Selected Studies

3. Results

3.1. Study Design and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Interventions Implemented to Alleviate Depression Symptoms in Women with Breast Cancer

3.3. Psychotherapy

3.4. Yoga

3.5. Physical Activity

3.6. Dance Therapy

3.7. Music Therapy

3.8. Effects on the Other Psychological Symptoms: Anxiety, Stress, and Sleep Levels

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeSantis, C.E.; Ma, J.; Gaudet, M.M.; Newman, L.A.; Miller, K.D.; Sauer, A.G.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, R.R.; Lengacher, C.A.; Alinat, C.B.; Kip, K.E.; Paterson, C.; Ramesar, S.; Han, H.S.; Ismail-Khan, R.; Johnson-Mallard, V.; Moscoso, M.; et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Post-Treatment Breast Cancer Patients: Immediate and Sustained Effects Across Multiple Symptom Clusters. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammen, C. Stress and Depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, J.; Mafla-España, M.A.; Torregrosa, M.D.; Cauli, O. Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Treatment Worsens Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality in Postmenopausal Women with Localized Breast Cancer: A One-Year Follow-up Study. Breast 2022, 66, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, M.J.; Cho, M.H.; Cooper, B.A.; Miaskowski, C. The Effect of Symptom Clusters on Functional Status and Quality of Life in Women with Breast Cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenne Sarenmalm, E.; Browall, M.; Gaston-Johansson, F. Symptom Burden Clusters: A Challenge for Targeted Symptom Management. A Longitudinal Study Examining Symptom Burden Clusters in Breast Cancer. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengacher, C.A.; Reich, R.R.; Post-White, J.; Moscoso, M.; Shelton, M.M.; Barta, M.; Le, N.; Budhrani, P. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction in Post-Treatment Breast Cancer Patients: An Examination of Symptoms and Symptom Clusters. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 35, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, P.; Heidrich, D. Symptom Clusters in Advanced Illness. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 21, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Son, B.H.; Hwang, S.Y.; Han, W.; Yang, J.H.; Lee, S.; Yun, Y.H. Fatigue and Depression in Disease-Free Breast Cancer Survivors: Prevalence, Correlates, and Association with Quality of Life. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2008, 35, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Brand, J.S.; Fang, F.; Chiesa, F.; Johansson, A.L.V.; Hall, P.; Czene, K. Time-Dependent Risk of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress-Related Disorders in Patients with Invasive and in Situ Breast Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Chan, M.; Bhatti, H.; Halton, M.; Grassi, L.; Johansen, C.; Meader, N. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Adjustment Disorder in Oncological, Haematological, and Palliative-Care Settings: A Meta-Analysis of 94 Interview-Based Studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, H.; Williams, R.; Funston, G.; Stanway, S.; Bhaskaran, K. Associations between Breast Cancer Survivorship and Adverse Mental Health Outcomes: A Matched Population-Based Cohort Study in the United Kingdom. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunsell, E.; Brisson, J.; Deschi’nes, L. Psychological Distress After Initial Treatment of Breast Cancer Assessment of Potential Risk Factors. Cancer 1992, 70, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramp, F.; Hewlett, S.; Almeida, C.; Kirwan, J.R.; Choy, E.H.S.; Chalder, T.; Pollock, J.; Christensen, R. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD008322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobeanu, O.; David, D. Alleviation of Side Effects and Distress in Breast Cancer Patients by Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2018, 25, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, G.A.; Doherty, S.; Whitford, D.L.; Khashan, A.S. Psychological Interventions for Women with Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD008729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Carson-Stevens, A.; Gillespie, D.; Edwards, A.G.K. Psychological Interventions for Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Polini, C.; Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Boncompagni, I.; Casagrande, M. The Effectiveness of Psychological Treatments in Women with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.T.H.; Fong, T.C.T.; Lo, P.H.Y.; Ho, S.M.Y.; Lee, P.W.H.; Leung, P.P.Y.; Spiegel, D.; Chan, C.L.W. Randomized Controlled Trial of Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy and Body-Mind-Spirit Intervention for Chinese Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4929–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lengacher, C.A.; Reich, R.R.; Paterson, C.L.; Ramesar, S.; Park, J.Y.; Alinat, C.; Johnson-Mallard, V.; Moscoso, M.; Budhrani-Shani, P.; Miladinovic, B.; et al. Examination of Broad Symptom Improvement Resulting from Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Du, K.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Shou, M.; Hu, B.; Jiang, P.; Dong, N.; He, L.; Liang, S.; et al. A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Cognitive Behavior Therapy on Quality of Life and Psychological Health of Breast Cancer Survivors and Patients. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, C.; Leydon, G.M.; Hoffman, C.J.; Copson, E.R.; Prescott, P.; Chorozoglou, M.; Lewith, G. Mindfulness for the Self-Management of Fatigue, Anxiety, and Depression in Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafaei, F.; Azizi, M.; Jalali, A.; Salari, N.; Abbasi, P. Effect of Exercise on Depression and Fatigue in Breast Cancer Women Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, M.; Kose, E.; Odabas, I.; Bingul, B.M.; Demirci, D.; Aydin, Z. The Effect of Exercise on Life Quality and Depression Levels of Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Cruickshank, S.; Noblet, M. Specialist Breast Care Nurses for Support of Women with Breast Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD005634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutiño-Escamilla, L.; Piña-Pozas, M.; Tobías Garces, A.; Gamboa-Loira, B.; López-Carrillo, L. Non-Pharmacological Therapies for Depressive Symptoms in Breast Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Breast 2019, 44, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salchow, J.L.; Strunk, M.A.; Niels, T.; Steck, J.; Minto, C.A.; Baumann, F.T. A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial About the Influence of Kyusho Jitsu Exercise on Self-Efficacy, Fear, Depression, and Distress of Breast Cancer Patients within Follow-up Care. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 15347354211037955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, J.M.; Scott, E.J.; Daley, A.J.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Mutrie, N.; Crank, H.; Powers, H.J.; Coleman, R.E. Effects of an Exercise and Hypocaloric Healthy Eating Intervention on Indices of Psychological Health Status, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Regulation and Immune Function after Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Liu, M.; Dang, S.; Wang, D.; Xin, X. A Clinical Randomized Controlled Trial of Music Therapy and Progressive Muscle Relaxation Training in Female Breast Cancer Patients after Radical Mastectomy: Results on Depression, Anxiety and Length of Hospital Stay. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.O.; Cohn, M.A.; Dunn, L.B.; Melisko, M.E.; Morgan, S.; Penedo, F.J.; Salsman, J.M.; Shumay, D.M.; Moskowitz, J.T. A Randomized Pilot Trial of a Positive Affect Skill Intervention (Lessons in Linking Affect and Coping) for Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Geng, W.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J. Effect of One Comprehensive Education Course to Lower Anxiety and Depression among Chinese Breast Cancer Patients during the Postoperative Radiotherapy Period—One Randomized Clinical Trial. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanctôt, D.; Dupuis, G.; Marcaurell, R.; Anestin, A.S.; Bali, M. The Effects of the Bali Yoga Program (BYP-BC) on Reducing Psychological Symptoms in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: Results of a Randomized, Partially Blinded, Controlled Trial. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2016, 13, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yeung, N.C.Y.; Tsai, W.; Kim, J.H.J. The Effects of Culturally Adapted Expressive Writing Interventions on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms among Chinese American Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2023, 161, 104244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Bennett, J.M.; Andridge, R.; Peng, J.; Shapiro, C.L.; Malarkey, W.B.; Emery, C.F.; Layman, R.; Mrozek, E.E.; Glaser, R. Yoga’s Impact on Inflammation, Mood, and Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Jáuregui, T.; Téllez, A.; Juárez-García, D.; García, C.H.; García, F.E. Clinical Hypnosis and Music In Breast Biopsy:A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2018, 61, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.K.; MacDermott, K.; Amarasekara, S.; Pan, W.; Mayer, D.; Hockenberry, M. Reimagine: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online, Symptom Self-Management Curriculum among Breast Cancer Survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taso, C.J.; Lin, H.S.; Lin, W.L.; Chen, S.M.; Huang, W.T.; Chen, S.W. The Effect of Yoga Exercise on Improving Depression, Anxiety, and Fatigue in Women with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 22, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Kang, S.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.Y. Beneficial Effect of Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy in Patients with Breast Cancer—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Explor. J. Sci. Heal. 2016, 12, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandwani, K.D.; Perkins, G.; Nagendra, H.R.; Raghuram, N.V.; Spelman, A.; Nagarathna, R.; Johnson, K.; Fortier, A.; Arun, B.; Wei, Q.; et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of Yoga in Women with Breast Cancer Undergoing Radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethorst, C.D.; Carmody, T.J.; Argenbright, K.E.; Mayes, T.L.; Hamann, H.A.; Trivedi, M.H. Considering Depression as a Secondary Outcome in the Optimization of Physical Activity Interventions for Breast Cancer Survivors in the PACES Trial: A Factorial Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Wei, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Lyu, J.; Jiang, X. Effects of Nurse-Led Supportive-Expressive Group Intervention for Post-Traumatic Growth among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2022, 54, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, F.; Sawatzky, R.; Öhlén, J.; Karlsson, P.; Koinberg, I. Challenges of Evaluating a Computer-Based Educational Programme for Women Diagnosed with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.Q.; Kwok, S.W.H.; Tan, J.Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.L.; Bressington, D.; Chen, S.L.; Huang, H.Q. The Effect of an Evidence-Based Tai Chi Intervention on the Fatigue-Sleep Disturbance-Depression Symptom Cluster in Breast Cancer Patients: A Preliminary Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 61, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Qiu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, C.; Mao, G.; Mao, S.; Lin, Y.; Shen, S.; Li, C.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Chinese Women with Breast Cancer. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, W.; Kaba, M.; Labisso, W.L.; Tigeneh, W.; Sahile, Z.; Zergaw, A.; Ejigu, A.; Baheretibeb, Y.; Gufue, Z.H.; Haileselassie, W. The Effect of Interpersonal Psychotherapy on Quality of Life among Breast Cancer Patients with Common Mental Health Disorder: A Randomized Control Trial at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, B.G.; Dunn-Henriksen, A.K.; Kroman, N.; Johansen, C.; Andersen, K.G.; Andersson, M.; Mathiesen, U.B.; Vibe-Petersen, J.; Dalton, S.O.; Envold Bidstrup, P. The Effects of Individually Tailored Nurse Navigation for Patients with Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer: A Randomized Pilot Study. Acta Oncol. (Madr.) 2017, 56, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Min, Q.W.; Lei, T.; Na, Z.X.; Li, L.; Jing, L. The Health Effects of Baduanjin Exercise (a Type of Qigong Exercise) in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized, Controlled, Single-Blinded Trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 39, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M.E.; Weißflog, G.; Leuteritz, K.; Wiltink, J.; Haselbacher, A.; Ruckes, C.; Kuhnt, S.; Barthel, Y.; Imruck, B.H.; Zwerenz, R.; et al. Efficacy of Short-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (STPP) with Depressed Breast Cancer Patients: Results of a Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E.; Crosswell, A.D.; Stanton, A.L.; Crespi, C.M.; Winston, D.; Arevalo, J.; Ma, J.; Cole, S.W.; Ganz, P.A. Mindfulness Meditation for Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer 2015, 121, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, S.J.; Buzaglo, J.S.; Lieberman, M.A.; Golant, M.; Greener, J.R.; Davey, A. Comparing Standard Versus Prosocial Internet Support Groups for Patients With Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Helper Therapy Principle. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.R.; Song, M.; Jung, K.H.; Yu, B.J.; Lee, K.J. The Effects of Mind Subtraction Meditation on Breast Cancer Survivors’ Psychological and Spiritual Well-Being and Sleep Quality: A Randomized Controlled Trial in South Korea. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidstrup, P.E.; Johansen, C.; Kroman, N.; Belmonte, F.; Duriaud, H.; Dalton, S.O.; Andersen, K.G.; Mertz, B. Effect of a Nurse Navigation Intervention on Mental Symptoms in Patients With Psychological Vulnerability and Breast Cancer: The REBECCA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2319591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredal, I.S.; Kåresen, R.; Smeby, N.A.; Espe, R.; Sørensen, E.M.; Amundsen, M.; Aas, H.; Ekeberg, Ø. Effects of a Psychoeducational versus a Support Group Intervention in Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, K.S.; Han, K.; Kim, H.W. A Psychological Intervention Programme for Patients with Breast Cancer under Chemotherapy and at a High Risk of Depression: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, T.A.; Segrin, C.; Sikorskii, A.; Pasvogel, A.; Weihs, K.; Lopez, A.M.; Chalasani, P. Randomized Controlled Trial of Supportive Care Interventions to Manage Psychological Distress and Symptoms in Latinas with Breast Cancer and Their Informal Caregivers. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, E.R.; O’Connor, M.; Kaldo, V.; Højris, I.; Borre, M.; Zachariae, R.; Mehlsen, M. Internet-Delivered Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E.; Partridge, A.H.; Wolff, A.C.; Thorner, E.D.; Irwin, M.R.; Joffe, H.; Petersen, L.; Crespi, C.M.; Ganz, P.A. Targeting Depressive Symptoms in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: The Pathways to Wellness Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Meditation and Survivorship Education. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhang, H.; Cui, N.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Cao, F. The Efficacy and Mechanisms of a Guided Self-Help Intervention Based on Mindfulness in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer 2021, 127, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji Lahiji, M.; Sajadian, A.; Haghighat, S.; Zarrati, M.; Dareini, H.; Raji Lahiji, M.; Razmpoosh, E. Effectiveness of Logotherapy and Nutrition Counseling on Psychological Status, Quality of Life, and Dietary Intake among Breast Cancer Survivors with Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7997–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desautels, C.; Savard, J.; Ivers, H.; Savard, M.H.; Caplette-Gingras, A. Treatment of Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Cognitive Therapy and Bright Light Therapy. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boing, L.; Baptista, F.; Pereira, G.S.; Sperandio, F.F.; Moratelli, J.; Cardoso, A.A.; Borgatto, A.F.; de Azevedo Guimarães, A.C. Benefits of Belly Dance on Quality of Life, Fatigue, and Depressive Symptoms in Women with Breast Cancer—A Pilot Study of a Non-Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2018, 22, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, C.; Markowitz, J.C.; Hellerstein, D.J.; Nezu, A.M.; Wall, M.; Olfson, M.; Chen, Y.; Levenson, J.; Onishi, M.; Varona, C.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Problem Solving Therapy, and Supportive Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder in Women with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, L.Q.; Courneya, K.S.; Anton, P.M.; Verhulst, S.; Vicari, S.K.; Robbs, R.S.; McAuley, E. Effects of a Multicomponent Physical Activity Behavior Change Intervention on Fatigue, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptomatology in Breast Cancer Survivors: Randomized Trial. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.J.; Hunter, G.R.; Norian, L.A.; Turan, B.; Rogers, L.Q. Ease of Walking Associates with Greater Free-Living Physical Activity and Reduced Depressive Symptomology in Breast Cancer Survivors: Pilot Randomized Trial. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedian, E.; Bahreini, M.; Ghasemi, N.; Mirzaei, K. Group Meta-Cognitive Therapy and Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Ma, L.; Chen, J. Effect of Mindfulness Yoga on Anxiety and Depression in Early Breast Cancer Patients Received Adjuvant Chemotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 2549–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, V.; Zanjani, Z.; Omidi, A.; Sarvizadeh, M. Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on Depression, Pain Acceptance, and Psychological Flexibility in Married Women with Breast Cancer: A Pre- and Post-Test Clinical Trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 43, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkol-Solakoglu, S.; Hevey, D. Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Survivors: Results from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychooncology 2023, 32, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ng, M.S.N.; Choi, K.C.; So, W.K.W. Effects of a 16-Week Dance Intervention on the Symptom Cluster of Fatigue-Sleep Disturbance-Depression and Quality of Life among Patients with Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 133, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getu, M.A.; Wang, P.; Addissie, A.; Seife, E.; Chen, C.; Kantelhardt, E.J. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Integrated with Activity Pacing on Cancer-Related Fatigue, Depression and Quality of Life among Patients with Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy in Ethiopia: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 2541–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagl, J.M.; Antoni, M.H.; Lechner, S.C.; Bouchard, L.C.; Blomberg, B.B.; Glück, S.; Derhagopian, R.P.; Carver, C.S. Randomized Controlled Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management in Breast Cancer: A Brief Report of Effects on 5-Year Depressive Symptoms. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagl, J.M.; Bouchard, L.C.; Lechner, S.C.; Blomberg, B.B.; Gudenkauf, L.M.; Jutagir, D.R.; Glück, S.; Derhagopian, R.P.; Carver, C.S.; Antoni, M.H. Long-Term Psychological Benefits of Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management for Women with Breast Cancer: 11-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer 2015, 121, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salkind, N. Beck Depression Inventory. Encycl. Meas. Stat. 2013, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Thibodeau, M.A.; Teale, M.J.N.; Welch, P.G.; Abrams, M.P.; Robinson, T.; Asmundson, G.J.G. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: A Review with a Theoretical and Empirical Examination of Item Content and Factor Structure. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D.; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 365, l1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passik, S.D.; Kirsh, K.L.; Donaghy, K.B.; Theobald, D.E.; Lundberg, J.C.; Holtsclaw, E.; Dugan, W.M. An Attempt to Employ the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale as a “lab Test” to Trigger Follow-up in Ambulatory Oncology Clinics: Criterion Validity and Detection. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for Depression in Well Older Adults: Evaluation of a Short Form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a Measure of Current Depression in the General Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, P.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. POMS Manual, 2nd ed.; Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- KKarlin, B.E.; Creech, S.K.; Grimes, J.S.; Clark, T.S.; Meagher, M.W.; Morey, L.C. The Personality Assessment Inventory with chronic pain patients: Psychometric properties and clinical utility. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 1571–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Carmody, T.J.; Arnow, B.; Klein, D.N.; Markowitz, J.C.; Ninan, P.T.; Kornstein, S.; Manber, R.; et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): A Psychometric Evaluation in Patients with Chronic Major Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Phillips, M.; Liu, J.; Cai, M.; Sun, S.; Huang, M. Validity and Reliability of the Chinese Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 152, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.; Smith, A.; Gibbons, C.; Alonso, J.; Valderas, J. The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): A View from the UK. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2018, 9, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAMILTON, M. Development of a Rating Scale for Primary Depressive Illness. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1967, 6, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sato, Y.; Takita, Y.; Tamura, N.; Ninomiya, A.; Kosugi, T.; Sado, M.; Nakagawa, A.; Takahashi, M.; Hayashida, T.; et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Distress, Fear of Cancer Recurrence, Fatigue, Spiritual Well-Being, and Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer—A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, L.K.; Monsef, I.; Wöckel, A.; Skoetz, N. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD011518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, G.M.; Jensen, J.L. Small Group Process and Outcome Research Highlights: A 25-Year Perspective. Int. J. Group. Psychother. 2017, 67, S194–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tan, H.; Yu, S.; Yin, H.; Baxter, G.D. The Effectiveness of Tai Chi in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 38, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannopollo, L.; Cristaldi, G.; Borgese, C.; Sommacal, S.; Silvestri, G.; Serpentini, S. Mindfulness Meditation as Psychosocial Support in the Breast Cancer Experience: A Case Report. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedlowski, M.; Enck, P.; Rief, W.; Bingel, U. Neuro-Bio-Behavioral Mechanisms of Placebo and Nocebo Responses: Implications for Clinical Trials and Clinical Practice. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 697–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enck, P.; Zipfel, S. Placebo Effects in Psychotherapy: A Framework. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FRANK, J.D. The Influence of Patients’ and Therapists’ Expectations on the Outcome of Psychotherapy. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1968, 41, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finniss, D.G.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Miller, F.; Benedetti, F. Biological, Clinical, and Ethical Advances of Placebo Effects. Lancet 2010, 375, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colloca, L.; Benedetti, F. Placebo Analgesia Induced by Social Observational Learning. PAIN® 2009, 144, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enck, P.; Bingel, U.; Schedlowski, M.; Rief, W. The Placebo Response in Medicine: Minimize, Maximize or Personalize? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-López, G.; Engler, H.; Niemi, M.B.; Schedlowski, M. Expectations and Associations That Heal: Immunomodulatory Placebo Effects and Its Neurobiology. Brain Behav. Immun. 2006, 20, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F. Mechanisms of Placebo and Placebo-Related Effects across Diseases and Treatments. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 48, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuchter, A.F.; Cook, I.A.; Witte, E.A.; Morgan, M.; Abrams, M. Changes in Brain Function of Depressed Subjects during Treatment with Placebo. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, P.; Dietrich, T.; Fransson, P.; Andersson, J.; Carlsson, K.; Ingvar, M. Placebo in Emotional Processing—Induced Expectations of Anxiety Relief Activate a Generalized Modulatory Network. Neuron 2005, 46, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Casado, A.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; de Pedro, C.G.; Méndez-Otero, M.; Romero-Elías, M. Cancer-Related Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Review. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, A.; Jacobs, J.; Haggett, D.; Jimenez, R.; Peppercorn, J. Evaluation and Management of Insomnia in Women with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 181, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaras, K.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Mitsi, D.; Veneti, A.; Kelesi, M.; Zyga, S.; Fradelos, E.C. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueboonthavatchai, P. Prevalence and Psychosocial Factors of Anxiety and Depression in Breast Cancer Patients. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2007, 90, 2164–2174. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Number of Participants | Clinical Stage | Treatment | Instrument Used to Evaluate Depression | Depression Severity | Description of the Intervention/Intervention Type | Results in Terms of the Symptoms of Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Aydin et al., 2021) [24] | Experimental group: 24 Control group: 24 | Did not specify | Had undergone partial or total breast surgery for breast cancer and had not developed metastasis. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [73] | Mild to moderate depression. | The study group received a 12-week aerobic exercise programme at the gym and a home-based resistance exercise program. | This study showed that aerobic and resistance exercises improved and decreased levels of depression. |

| (Bower et al., 2021) [57] | Experimental groups: MAP: 85 SE: 81 Control group: 81 | I, II, III | The patients had received surgery, RT, and chemotherapy 6 months before the intervention. | Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). A score of 16 or higher on this scale indicates the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms [74]. | Mild to moderate depression. | The mindful awareness practises (MAP) intervention consisted of theoretical sessions on mindfulness, relaxation, and mind–body connection. The sessions were held for 2 h weekly for 6 weeks. Survivor education (SE) was a standard educational programme that covered important topics, such as quality of life post-BC, medical management after treatment, work–life balance, body image, sexuality, nutrition and physical activity, the impact of cancer in families, and genetics. These sessions were also conducted in groups, with weekly 2 h meetings for 6 weeks. | Reductions in depression symptoms from pre-intervention to post-intervention were observed in both experimental groups compared to the control group. |

| (Liu et al., 2022) [66] | Experimental group: 68 Control group: 68 | I, II | All the patients received surgery and postoperative chemotherapy. | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression (HADS), having 10–21 points is indicative of significant symptoms of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | The experimental group participated in weekly mindfulness yoga sessions that included meditation, breathing-focused yoga poses, and discussions, alongside conventional care for 8 weeks. The control group received routine nursing interventions during the same period, which included psychological care, dietary counselling, health education, telephone follow-ups, and lifestyle counselling. | The experimental group, which practised mindfulness yoga along with conventional mindfulness, significantly improved compared to the control group, especially in terms of depression. |

| (Ghorbani et al., 2021) [67] | Experimental group: 20 Control group: 20 | Did not specify. | Did not specify. | The tool was the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), having a score ≥10 indicates depressive symptoms [76]. | Severe depression. | Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) sessions were conducted by a psychotherapist and consisted of 8 weekly sessions lasting 90 min each. The control group received no intervention but did receive ACT 4 months later. | Compared to the control group, ACT treatment significantly reduced the mean depression scores and psychological flexibility significantly increased. |

| (Akkol-Solakoglu and Hevey 2023) [68] | Experimental group: 53 Control group: 23 | I–IV | The patients had completed primary treatment and were BC survivors. | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure anxiety and depression symptoms. A score between 10 and 21 suggests the presence of significant symptoms of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | The internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) programme was a seven-module, 8-week intervention based on a transdiagnostic approach to depression and anxiety offered through the SilverCloud platform. iCBT in the intervention group aimed to improve the knowledge of BC survivors of their experience and their symptom management skills. The control group continued with the usual care (UC) recommended by their healthcare team. | Although the difference was not significant, the experimental group exhibited lower depression scores compared to the control group after the intervention. This disparity reached statistical significance during the 2-month follow-up. |

| (He et al., 2022) [69] | Experimental group: 88 Control group: 88 | I–III, recently diagnosed. | The patients had received surgery and were scheduled for chemotherapy. | Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9). The total score ranges from 0 (no depression) to 27 (severe depression) [77]. | Does not specify. | A Chinese folk ‘square dance’ characterised by its simple steps was adapted for BC patients. The intervention included six instructional sessions in the hospital. The first one lasted 1 h and the others were 30 min, each with short breaks. Additionally, the patients were asked to practice at home for 16 weeks, spending 150 min a week dancing. The control group received a health consultation for 16 weeks as part of the treatment. | Participants who carried out the dance intervention for 16 weeks reported a lower incidence of depression compared to the control group. |

| (Getu et al., 2023 [70] | Experimental group: 30 Control group: 28 | I–IV | The patients were receiving chemotherapy. | Depression assessment was performed using the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9). The total score ranges from 0, indicating no depression, to 27, indicating severe depression [78]. | Does not specify. | The experimental group received seven sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy activity stimulation (CBT-AP) during chemotherapy, with three face-to-face group sessions lasting 2 h and 4 individual telephone sessions lasting 30 min. The control group received UC. | Compared to the control group, the experimental group had lower depression scores. |

| (Salchow et al., 2021) [27] | Experimental group: 30 Control group: 20 | Did not specify. | The patients had completed treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone therapy, and had received antibodies 6 months before the intervention. | The level of fear and depression was quantified using the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), having >10 points is indicative of significant symptoms of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | The intervention group participated in a Kyusho Jitsu intervention twice a week for 6 months; the control group received no intervention. | There were no significant differences between the groups regarding symptoms of depression, although there was a significant reduction in the anxiety subscale from baseline to 6 months in the intervention group. |

| (Saxton et al., 2014) [28] | Experimental group: 44 Control group: 41 | I–III | The patients had completed surgery, RT, and chemotherapy treatment in the 18 months prior. | Depressive symptoms were assessed using the BDI (Beck Depression Inventory version II: BDI-II) which has a range from 0 to 63 with a cut off ≥14 [73]. | Mild depression. | The 24-week lifestyle intervention combined three supervised exercise sessions each week with a personalised, low-calorie healthy eating programme. The exercise sessions comprised 30 min of aerobic exercise. | Compared to the control group, the intervention group showed a reduction in depression symptoms. |

| (Zhou et al., 2015) [29] | Experimental group: 85 Control group: 85 | Did not specify. | The patients were scheduled to undergo a radical mastectomy. | The Zung Depression Self-Rating Scale (ZSDS) was used. The Chinese ZSDS is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of depression. The sum of the 20 items produces a score that ranges between 20 and 80, with a higher score demonstrating greater depression [79]. | Does not specify. | Two therapeutic techniques were used in the post-mastectomy experimental group: music therapy and muscle relaxation training. Music therapy involved listening to music chosen by the patients twice a day for 30 min (from 6:00 to 8:00 A.M. and 9:00 to 11:00 P.M.) within 48 h of surgery and until hospital discharge. A muscle relaxation training programme with two daily 30 min sessions was simultaneously implemented. The control group received UC. | A significant improvement in depression levels was observed in the experimental group compared to the control group. The implementation of music therapy and progressive muscle relaxation training appeared to reduce both depression and the length of hospitalisation in female patients with BC after radical mastectomy. |

| (Cheung et al., 2017) [30] | Experimental group: 26 Control group: 13 | IV B metastatic BC. | Did not specify. | Depression was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | Mild depression. | The LILAC intervention consisted of 5 weekly 1 h sessions in which the participants learned eight evidence-based skills designed to increase the frequency of positive emotions. The participants in the in-person control condition also received individual 5 h sessions. The control sessions consisted of an interview without a didactic intervention or skills practice. | The participants in the experimental group who received a combination of in-person and online therapy exhibited decreased levels of depression and negative affect at the 1-month follow-up. |

| (Li et al., 2018) [31] | Experimental group: 145 Control group: 136 | I–IV | The patients had received conservative surgery and were receiving RT. | The level of anxiety and depression was measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). A score above 10 indicates high levels of anxiety and depression [75]. | Mild depression. | In the intervention group, a 3 h comprehensive educational course on psychological stress and management skills was taught. In the control group, all the patients were offered a basic 15 min educational course on BC and RT on their day of admission, according to the UC guidelines of the hospital. | Both anxiety and depression scores increased during RT. Furthermore, this trial concluded that a comprehensive educational course on BC, with an emphasis on teaching stress management skills, did not lead to significant changes in depression scores over the 5 to 6 weeks of RT. |

| (Lanctôt et al., 2016) [32] | Experimental group: 58 Control group: 43 | I–III | The patients were receiving chemotherapy. | Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory, version II (BDI-II), whose scores ranges from 0 to 63. The scores are interpreted as follows: 0–10 (normal), 11–16 (mild disturbance), 17–20 (borderline clinical depression), 21–30 (moderate depression), 31–40 (severe depression), and more than 40 (extreme depression) [73]. | Mild depression. | The Bali Yoga Programme for BC patients (BYP-BC) consisted of 23 gentle hatha asanas (postures), 2 prayanamas (breathing techniques), shavasanas (‘corpse’ relaxation postures), and psychoeducational topics. The participants attended 8 weekly sessions lasting 90 min each and received a DVD with 20 and 40 min sessions to practice with at home. The participants in the waitlist control group received UC for 8 weeks and then received the same intervention. | The symptoms of depression increased in the control group and no significant changes were recorded in the experimental group. However, a reduction in depression symptoms was observed in the control group after receiving the BYP-BC intervention. |

| (Lu et al., 2023) [33] | Experimental groups: SR: 46 ESR: 54 CF: 36 | 0–IV | The patients had completed primary treatment surgery, RT, and chemotherapy within the 5 years prior. | The 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. A higher score indicates more depressive symptoms (total score ranged from 0 to 30) [80]. | Does not specify | The study divided the participants into three conditions: greater self-regulation (ESR), self-regulation (SR), and facts about cancer (CF). The ESR group wrote about stressful cancer-related experiences and coping strategies in the first week, deep feelings about BC in the second week, and positive thoughts about the experience in the third week. The SR group did the same, but the order of weeks 1 and 2 was changed. The CF group wrote objectively about their diagnosis and treatment. | The ESR group showed improvements in the symptoms of depression, unlike the other two groups, which did not show any significant differences. |

| (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2014) [34] | Experimental group: 100 Control group: 100 | 0–IIIa | The patients had finished treatment with aromatase inhibitors and were BC survivors. | The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) assessed depressive symptoms in the last week [74]. | Does not specify. | The participants were assigned either to a wait-list control or a group that practised 12 weeks of twice-weekly 90 min hatha yoga classes. | The groups did not differ in terms of depression at any time. Secondary analyses showed that the frequency of yoga practice was strongly associated with fatigue but not with depression. |

| (Sánchez-Jáuregui et al., 2018) [35] | Experimental groups Hypnosis: 58 Music: 55 Control group: 57 | Did not specify. | The patients were scheduled to receive a breast biopsy. | To evaluate anxiety and depression, the HADS scale (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) was used. A score >10 indicates high levels of anxiety and depression [75]. | Does not specify. | There were two experimental groups (hypnosis or music therapy) and one control group, with three measurement times: baseline, (the period prior to the intervention) pot-intervention but pre-biopsy, and at the end of the breast biopsy. The hypnosis group received a recorded audio hypnosis intervention. The music group listened to the background music, without the suggestions, for the same period. Patients in the control group spent 17 min in the waiting room. | The results showed a statistically significant reduction in depression in the hypnosis and music groups compared to the control group. Before the biopsy, hypnosis significantly decreased depression levels compared to the music alone, but after the biopsy, there were no differences between the two groups. |

| (Smith et al., 2019) [36] | Experimental group: 37 Control group: 52 | Did not specify. | Did not specify. The patients were BC survivors. | The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) was used to capture symptoms of depression. With a cut-off point ≥10 to define current depression [81]. | Mild depression. | The Reimagine (symptom self-monitoring) curriculum consisted of web-based content and required activities including attending an online introductory group meeting, viewing videos, and completing mind–body and cognitive reframing exercises over an 18-week period. The programme also taught mind–body exercises such as guided imagery and meditation. The participants in the control group were offered the opportunity to complete Reimagine without cost at the end of the study period. | Reimagine resulted in significant reductions in depression symptoms in the experimental group participants compared to the control group. |

| (Taso et al., 2014) [37] | Experimental group: 30 Control group: 30 | I–III | The patients were receiving chemotherapy at the time of the study. | The mood profile scale was used, which includes 14 items to assess depression and anxiety (seven items each). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 to 4), where higher scores indicate higher levels of depression and anxiety [82]. | Does not specify. | A 60 min yoga exercise intervention, twice a week for 8 weeks, was implemented in the experimental group during their chemotherapy treatment. The control group received UC. | The 8-week intervention did not significantly improve depression levels in the experimental group. |

| (Jang et al., 2016) [38] | Experimental group: 12 Control group: 12 | 0–III | All the patients had completed active treatment with surgery, RT, and chemotherapy at least 2 years before the intervention. | The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) was used. PAI is a self-report survey comprising 344 questions. For this study, questions related to depression and anxiety were extracted [83]. | Mild depression. | The patients in the mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) group received 12 sessions lasting 45 min each. In addition, the Korean psychological intervention of mindfulness-based stress reduction (K-MBSR) was also applied to the mindfulness activities. | Depression decreased significantly in the experimental group. However, there were no significant changes in the control group. |

| (Chandwani et al., 2014) [39] | Experimental groups Yoga: 53 Stretching: 56 Control group: 54 | 0–III | The patients were scheduled to undergo RT. | Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) measures [74]. | Mild depression. | The participants in the yoga (YG) and stretching (ST) groups attended up to three classes lasting 60 min per week while undergoing 6 weeks of RT. | There were no differences in the symptoms of depression between the two groups. |

| (Rethorst et al., 2023) [40] | Did not specify. | I–IV | The patients had completed active treatment more than 3 years before registration and were BC survivors. | Depressive symptoms were measured using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR). The total score ranges between 0 and 27 points [84]. | Mild depression. | In the physical activity intervention, the participants were given the goal of completing 150 min of weekly moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) through a combination of supervised in-person sessions and unsupervised sessions. The active life every day (ALED) participants attended 12 bi-weekly educational sessions led by a trained interventionist, which aimed to support behavioural strategies to increase physical activity. | Results indicated that depression symptoms decreased significantly in the entire study sample during the 6-month intervention. The participants who received the ALED intervention experienced greater reductions in the symptoms of depression. |

| (Wang et al., 2022) [41] | Experimental group: 84 Control group: 84 | 0–III in newly diagnosed patients. | The patients were scheduled to receive surgery or chemotherapy. | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). A score >10 indicates high levels of anxiety and depression [75]. | Mild depression. | In a group expression intervention implemented during the systemic treatment process, the participants received four sessions of nurse-led support each lasting about 60 min, focussing on the following topics: ‘being patient’, ‘interpersonal relationships’, ‘the journey to recovery’, and ‘planning for the future’. The control group received health education, rehabilitation training, psychological support, and other nursing measures. | The participants in the experimental group reported more significant reductions in depression. |

| (Ventura et al., 2017) [42] | Experimental group: 105 Control group: 121 | I–III | Scheduled for surgery. | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). A score >10 indicates high levels of anxiety and depression [75]. | Does not specify. | An educational intervention with the computer-based Swedish Interactive Rehabilitation Information (SIRI) lectures led by various experts in cancer treatment (surgeons, oncologists, oncology nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, and counsellors), as well as a patient representative. The lectures were presented as Microsoft PowerPoint slides and took a combined time of 4 h. | Multilevel modelling revealed that this educational programme modality had no significant impact on outcomes over time. Compared to the control group, SIRI was not effective in improving patient depression levels. |

| (Yao et al., 2022) [43] | Experimental group: 36 Control group: 36 | I–III A, B, C | The patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy in the 2 months prior. | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression (HADS-D) was adopted to assess the participant’s depression, where a higher score indicates greater severity of depression [75]. | Moderate to severe depression. | All the participants received routine care including an educational pamphlet on self-management of cancer symptoms, while the participants in the Tai Chi group received an additional 8-week Tai Chi intervention with two sessions lasting 60 min per week. | Tai Chi appeared to be effective in relieving the symptoms of depression. The results showed significantly lower scores in the experimental group compared to the control group and baseline. |

| (Ren et al., 2019) [44] | Experimental groups CBT: 98 SCM: 98 Control group: 196 | I–III | The patients had received surgery, RT, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy. | Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Chinese version of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17). Participants with a HAMD-17 score of ≥8 were considered to have existing depressive symptoms [85]. | Mild depression. | There were two groups: (1) psychoeducational cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in which the therapist taught behavioural strategies such as meditation and distraction, emotional regulation skills, and social and psychological techniques; and (2) self-care management (SCM), designed to control for the effects of treatment expectations and professional care. Women in the CBT and SCM groups received nine sessions over 12 weeks, while women in the control group received only their UC. | CBT effectively reduced depression symptoms in the experimental group compared to the other two groups. Although the participants in the experimental group who received CBT had higher levels of depression at the beginning of the study, by the end, their scores decreased below the cutoff. |

| (Belay et al., 2022) [45] | Experimental group: 57 Control group: 57 | Patients with and without metastases. | The patients were receiving RT, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy. | Distress was measured using the distress thermometer, a numerical scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), with a cut-off point of ≥7. The level of depression and anxiety was measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut off ≥8 [75]. | Moderate depression. | Professional therapists trained in interpersonal psychotherapy administered the Interpersonal Psychotherapy Ethiopian version (IPT-E) intervention involving four to six therapy sessions lasting for 30 to 60 min each week, delivered in person. | IPT-E effectively reduced depression symptoms. |

| (Mertz et al., 2017) [46] | Experimental group: 25 Control group: 25 | Did not specify. | The patients had received surgery, RT, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy. | Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut-off score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | A personalised nursing navigation, which included individual counselling based on manuals incorporating cognitive therapy (CT) and psychoeducation strategies to motivate and support patients in the self-management of their symptoms and use of rehabilitation services. Patients in the control group received UC. | Compared to the control group, women in the intervention group reported significantly lower depression scores after 12 months. |

| (Ying et al., 2019) [47] | Experimental group: 46 Control group: 40 | I–IIIC | The patients had completed active treatment, surgery, chemotherapy, and RT in the 2 years prior and were BC survivors. | The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a validated nine-item tool to measure the severity of depression, with scores ranging from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression [77]. | Mild depression. | Over 6 months, the experimental group performed the Baduanjin exercises 3 days a week in the hospital and another 4 days a week at home. The control group was asked to maintain their original daily physical activity for no less than 30 min per day, for 6 months. The patients recorded their daily activities at home. | After completing this specific exercise for 6 months, there were significant improvements in the symptoms of depression in the experimental group compared to the control group. |

| (Beutel et al., 2014) [48] | Experimental group: 78 Control group: 79 | 0–III | The patients were recruited after surgery while still undergoing oncological treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, and hormonal treatment). | Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut-off score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. Depressive disorder according to SCID-I (ICD-10 diagnoses). | Depression clinic. | In the Short-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (STPP) study a treatment manual outlining specific strategies to address serious problems such as hopelessness or suicidal thoughts was used. Up to five preliminary sessions and 20 weekly therapy sessions were offered. The treatment ended when the agreed objectives were achieved. The control group received written information about local cancer counselling centres. | Unlike previous interventions, recruitment to this study required a diagnosis of depression; remission of depression was the primary outcome. Their analyses indicated that approximately twice as many patients (44%) achieved remission after STPP compared to the control group (23%). |

| (Bower et al., 2015) [49] | Experimental group: 39 Control group: 32 | 0–III | The patients had completed local and/or adjuvant oncological therapy (except hormonal therapy) at least 3 months previously. | Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) measures [74]. | Mild depression. | The intervention was based on the mindful awareness practises (MAP) programme. The participants met for 6 weekly 2 h group sessions that included the presentation of theoretical materials on mindfulness, relaxation, and the mind–body connection. | The MAP intervention produced significant short-term reductions in perceived stress and marginal reductions in depression symptoms. |

| (Lepore et al., 2014) [50] | Experimental groups: S-ISG: 96 P-ISG: 98 | I–II | The patients had received surgery, RT, and chemotherapy. | Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut-off score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | There were 2 manualised intervention conditions sharing many characteristics. Both groups had weekly 90 min live (synchronous) chats for 6 weeks. In the Standard Internet Support Groups (S-ISG), peer-to-peer information sharing and emotional support, normalisation of experiences, and promotion of skills and confidence to make positive life changes was emphasised. The Enhanced Prosocial Internet Support Groups (ISG P-ISG) group included all elements of the S-ISG but also received written advice on how to recognise and respond to the online support needs of others. | Relative to the S-ISG, the participants in the P-ISG condition had higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms following the intervention. The P-ISG did not produce better mental health outcomes in distressed BC survivors compared to the S-ISG. |

| (Yun et al., 2017) [51] | Experimental group: 22 Control group: 24 | I–III | The patients had completed surgery and/or adjuvant chemotherapy and/or RT after surgery up to 2 years prior and 6 months before the study. | Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) measures, which consisted of 20 items to measure depression symptoms [74]. | Mild depression. | The study consisted of a mental subtraction meditation (MSM) programme conducted twice a week for 8 weeks (16 sessions in total). Educational sessions on life after cancer treatment, health exercises, diet management, and follow-up were included. Full-scale meditation began in the fifth session. In comparison, the self-management education (SME) group received the same first 4 sessions as the MSM group, and then received lectures on relationship improvement, communication skills, and stress management. | The experimental group that received the MSM intervention reported a significant decrease in depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, compared to the SME control group. |

| (Bidstrup et al., 2023) [52] | Experimental group: 156 Control group: 153 | Did not specify. | The patients had received surgery, RT, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and trastuzumab. | The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a validated nine-item tool to measure the severity of depression, with scores ranging from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression [77]. | Moderate depression. | The study implemented the REBECCA nursing navigation intervention. Patients were randomly assigned to this intervention and received counselling and symptom screening by nurses in addition to UC. REBECCA has two components: detection of psychological and physical symptoms and nursing navigation and is delivered in about six individual sessions (the first one in person, and the rest by telephone) lasting approximately 60 min each. UC included regular treatment and nursing support at chemotherapy and RT appointments, as well as rehabilitation. | The nursing navigation and symptom screening provided in the REBECCA intervention showed promise in reducing several psychological symptoms. Significant effects were observed for depression symptoms at the 6-month follow-up. |

| (Bredal et al., 2014) [53] | Experimental groups: SG: 182 PEG: 185 | I–III | The patients had received surgery, RT, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy. | Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut-off score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | Psychoeducational groups (PEG) and support groups (SG) were compared. The PEG intervention consisted of 5 weekly 2 h sessions addressing health education, stress management, problem-solving skills, and psychological support. The SG received 3 weekly 2-h sessions. Both interventions sought to reduce the feeling of alienation and isolation by creating an environment of acceptance and providing support, information, and dispelling misperceptions and fears about adjuvant treatment. | Regarding depression, both the PEG and SG interventions produce improvements over time; However, there were no significant differences between the groups. |

| (Kim et al., 2018) [54] | Experimental group: 30 Control group: 30 | I–III | The patients were receiving chemotherapy. | Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with a cut-off score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. | Mild depression. | The nurse-led psychological intervention programme comprised 7 weekly counselling sessions delivered face-to-face and by telephone. The programme provided education on chemotherapy symptom management and skills for coping with negative emotions during BC treatment. | Compared to the control group, the intervention group reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression. |

| (Badger et al., 2020) [55] | Experimental groups: SHE: 114 TIPC: 116 | I–IV | The patients had finished active treatment a year prior and were BC survivors. | Depression and anxiety were assessed using eight-item short forms from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Higher scores equal more of the mastery being measured [86]. | Mild depression. | The telephone interpersonal counselling (TIPC) intervention focused on mood management, emotional expression, communication, interpersonal relationships, social support, and cancer information, with sessions lasting approximately 30 min for survivors and 29 min for caregivers. Supportive health education (SHE) focused on breast health, routine testing, treatment, side effects, and coping strategies, as well as lifestyle interventions such as nutrition and physical activity, with sessions lasting around 27 min for survivors and 24 min for caregivers. | The TIPC intervention produced lower depression scores compared to the SHE. |

| (Nissen et al., 2020) [56] | Experimental group: 82 Control group: 46 | Did not specify. | The patients had completed primary treatment for breast or prostate cancer and were cancer survivors. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest possible score is 63. Higher scores indicate the presence of depression [73]. | Mild depression. | An internet-delivered mindfulness-based CT (iMBCT) programme was developed in collaboration with representatives of cancer survivors. There were eight modules lasting 1 week. which included written material, audio exercises, writing tasks, specific cancer patient examples, and videos with patients and experts. | In the experimental group, depression outcomes improved immediately after the intervention. |

| (Shao et al., 2021) [58] | Experimental group: 72 Control group: 72 | I–IV | The patients were undergoing surgery and had received chemotherapy and RT. | The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a validated nine-item tool to measure the severity of depression, with scores ranging from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression [77]. | Mild depression. | Participants in the experimental group received guided self-help rooted in mindfulness-based stress reduction practises and CT. The patients were instructed to follow certain daily practices at home for 6 weeks, while the waiting list control group received UC with health education and follow-ups. | There were significant improvements in depression symptoms in the experimental group compared to waiting list controls, and these improvements were maintained at the 1- and 3-month follow-ups. |

| (Raji Lahiji et al., 2022) [59] | Experimental group: 46 Control group: 44 | 0–III C | The patients had completed active treatments at least 3 months before the study enrolment. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest possible score is 63. Higher scores indicate the presence of depression [73]. | Mild depression. | Over 2 months, the participants received four nutritional counselling sessions covering diet education, depression prevention and mood improvement recommendations, lasting 120 min. In addition to nutritional counselling, the participants in the combined intervention group attended weekly psychotherapy sessions based on logotherapy principles with the same delivery pattern. | After 8 weeks, the participants in speech therapy with nutrition education classes reported significantly lower depression scores compared to those participating in nutrition education classes alone. |

| (Desautels et al., 2018) [60] | Experimental groups: CT: 25 BLT: 26 Control group: 11 | 0–III | The patients had received active treatment: surgery, RT, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) [75], the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [73] and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [87]. | Mild depression. | The cognitive therapy (CT) group received 8 weekly sessions of approximately 60 min. The bright light therapy (BLT) participants were instructed to expose themselves to a 10,000-lux light box for 30 min every morning, before 10 a.m. The control group were contacted every 2 weeks to investigate the presentation of depression symptoms or suicidal ideation. | After treatment, there was a significant reduction in the symptoms of depression in patients who received CT compared to the CG, as measured by two different evaluation scales. The BLT participants showed a greater decrease in depression symptoms only on one scale when compared to the CG. |

| (Boing et al., 2018) [61] | Experimental group: 8 Control group: 11 | Did not specify. | At the time of the study, the patients were receiving hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, and RT. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest possible score is 63. Higher scores indicate the presence of depression [73]. | Mild depression. | The experimental group took 12 weeks of belly dance classes lasting 60 min each, twice a week. | Belly dancing significantly reduced the symptoms of depression in women with BC. |

| (Blanco et al., 2019) [62] | Experimental groups: IPT: 46 PST: 43 BSP: 45 | I–IV | Did not specify. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest possible score is 63. Higher scores indicate the presence of depression [73]. | Major depressive disorder. | There were three interventions lasting 45 min, delivered weekly for 12 sessions. Interpersonal psychotherapy (ITP) helps patients resolve a crisis in their functional or social environment, leading to an improvement in the symptoms of depression. Problem solving therapy (PST) is a cognitive behavioural intervention. The goal is to encourage the adoption and implementation of adaptive problem-solving attitudes and behaviours. Brief supportive psychotherapy (BSP) is an active treatment that uses techniques such as clarification, suggestions, praise, reassurance, normalisation, rehearsal, and anticipation to promote a supportive relationship between the patient and therapist. | No statistically significant differences were observed between the treatment groups, with all three brief psychotherapies showing similar improvements in depression symptoms, with large pre-post effect sizes. |

| (Rogers et al., 2017) [63] | Experimental group: 110 Control group: 112 | Ductal carcinoma in situ or stage I–IIIA BC. | The patients had completed the primary treatment of surgery, RT, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy less than 1 year prior and were BC survivors. | The 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) measured depression and anxiety symptomatology, with a cutoff score ≥8 indicating cases of anxiety or depression [75]. | Does not specify. | The 3-month social cognitive theory-based BEAT Cancer intervention included 12 supervised exercise sessions. The UC participants received publicly available printed materials from the American Cancer Society but were given no advice or instructions related to physical activity beyond these materials. | Compared with the control group, the symptoms of depression significantly improved in the BEAT Cancer intervention experimental group. |

| (Carter et al., 2018) [64] | Experimental group: 16 Control group: 11 | Ductal carcinoma in situ or stage I–IIIA BC. | The patients had not received chemotherapy or RT during the study period. | Self-reported depression was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in which higher scores corresponded to greater depression [75]. | Does not specify. | Individuals randomised to the physical activity behaviour change intervention (INT) completed 12 supervised exercise sessions. The exercise volume was increased so that during the final 4 weeks of the intervention, the participants performed at least 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise per week. Individuals randomly assigned to the control group received materials available from the American Cancer Society outlining recommendations for exercise and physical activity but no additional contact other than regular telephone check-ins with research staff. | Depression symptoms decreased from the baseline to the follow-up in the experimental group. |

| (Zahedian et al., 2021) [65] | Experimental group: 12 Control group: 12 | Did not specify. | The patients were receiving chemotherapy. | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest possible score is 63. Higher scores indicate the presence of depression [73]. | Mild to moderate depression. | Eight 90 min metacognitive therapy (MCT) sessions were delivered to the intervention group. Each week there was a group session in which tasks during and between sessions were set. The control group received UC for depression (except psychotherapy). | The mean depression score in the experimental group had reduced at the 1-month follow-up and there were no significant differences in the control group. |

| (Stagl, Antoni et al., 2015) [71] | Experimental group: 120 Control group: 120 | 0–IIIB | The patients had completed active treatments, surgery, RT, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy, and were BC survivors of 5 years. | Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with a cut off ≥16 [74]. | Does not specify. | The cognitive behavioural stress management (CBSM) intervention consisted of a 10-week group programme for women undergoing treatment for BC that combined CBT and relaxation techniques to reduce stress and negative mood. The control group received a 1-day psychoeducational seminar that provided information about BC but did not include structured stress management practises. | Women in the experimental group who received the CBSM intervention reported fewer depression symptoms than women in the control group at the 5-year follow-up. Psychosocial interventions in the early stages of treatment may influence the long-term psychological well-being of BC survivors. |

| (Stagl, Bouchard et al., 2015) [72] | Experimental group: 51 Control group: 49 | 0–IIIB | The patients had received surgery, chemotherapy, RT, and hormone therapy 8 to 15 years after enrolment in the study. | Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with a cut off ≥16 [74]. | Does not specify. | A 10-week CBSM intervention group programme for women undergoing treatment for BC that combined CBT and relaxation techniques to reduce stress and negative mood was implemented. The control group received a 1-day psychoeducational seminar that provided information about BC but did not include structured stress management practises. | The participants assigned to the CBSM reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression and those that received CBSM after surgery for early-stage BC reported lower depression symptoms than the control group up to 15 years later. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mafla-España, M.A.; Cauli, O. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing the Symptoms of Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Diseases 2025, 13, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030080

Mafla-España MA, Cauli O. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing the Symptoms of Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Diseases. 2025; 13(3):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030080

Chicago/Turabian StyleMafla-España, Mayra Alejandra, and Omar Cauli. 2025. "Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing the Symptoms of Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials" Diseases 13, no. 3: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030080

APA StyleMafla-España, M. A., & Cauli, O. (2025). Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing the Symptoms of Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Diseases, 13(3), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030080