Psychological Involvement in the Journey of a Patient with Localized Prostate Cancer—From Diagnosis to Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Introduction Regarding the Incidence of Prostate Cancer

1.2. The Associated Psychological Impact

1.3. Diagnosis, Staging and Psychological Impact

1.4. Available Treatments and Androgen Deprivation Therapy’s (ADT) Position in the Therapeutic Plan

2. Case Presentation

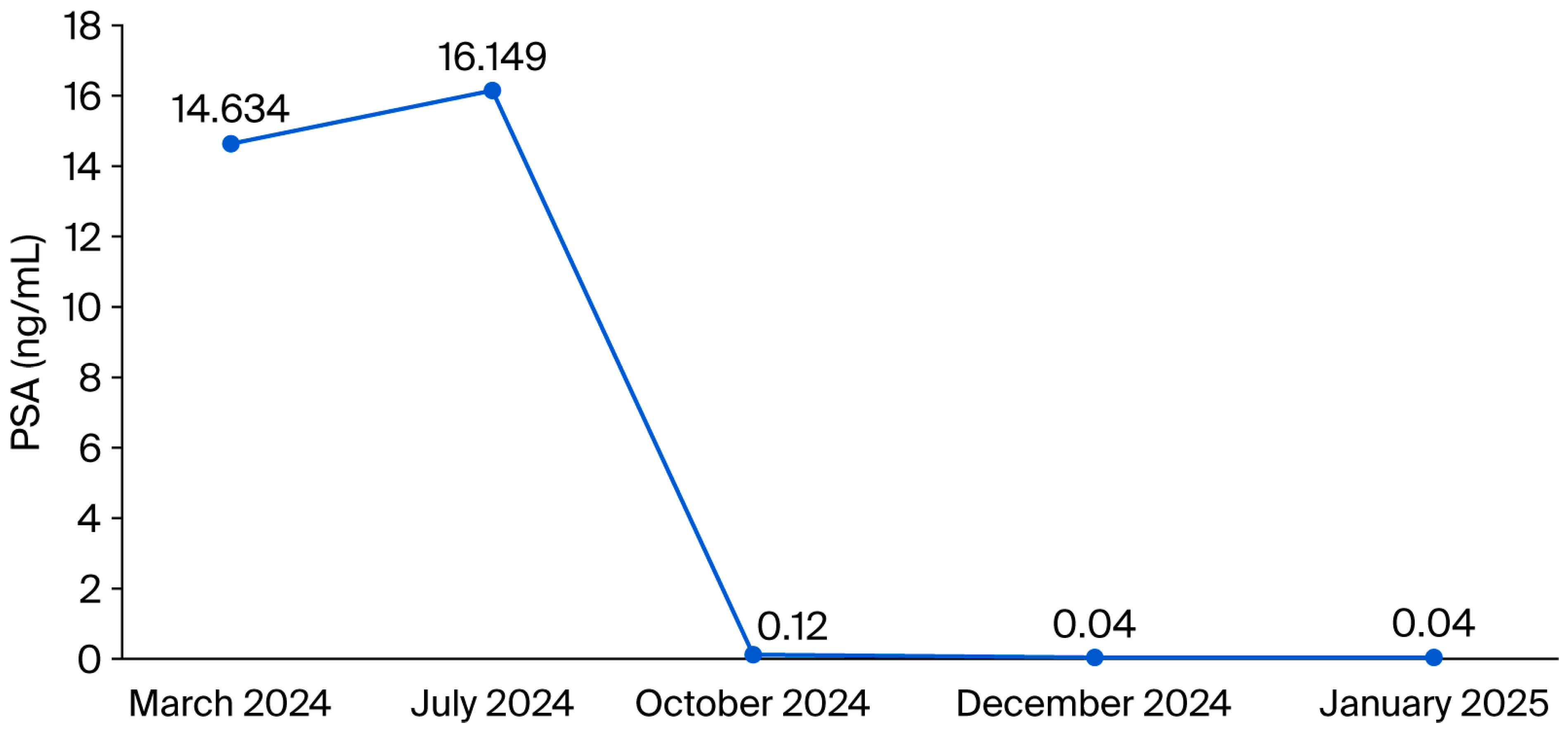

Pretherapeutic Assessment, Staging and Therapeutic Approach

- MAY 2024: CT of the thorax—A pulmonary lump of 1 cm was noticed (right inferior lobe), with recommendation for monitoring

- JULY 2024: Bone scan with 99mTc-HDP

- DECEMBER 2024—Progression of pulmonary lesion and undertaking the transthoracic puncture biopsy

- FEBRUARY 2025—The pathological result and the recommendation for immunohistochemistry

- Classification pTNM: pT4N0

3. Discussion

3.1. Sexual and Systemic Side Effects of ADT

3.2. The Psycho-Sexual Impact and the Importance of Intervention

3.3. The Psychological Impact and the Benefits of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in the Case of Our Study Patient

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | prostate cancer |

| PSA | prostate-specific antigen |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| ACT-ED | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Erectile Dysfunction |

| mpIRM | multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| ADT | androgen deprivation therapy |

| ARPIs | androgen receptor pathway inhibitors |

| TRUS-biopsy | ultrasound-guided transrectal biopsy |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin release hormone |

| LHRH | luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone |

| ESR | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ED | erectile dysfunction |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EM | Enhanced Monitoring |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer [Internet]. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- SEER*Explorer: An Interactive Website for SEER Cancer Statistics [Internet]. Surveillance Research Program. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.; Doveson, S.; Lindqvist, O.; Wennman-Larsen, A.; Fransson, P. Quality of life in men with metastatic prostate cancer in their final years before death–a retrospective analysis of prospective data. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.J.; Penson, D.F. Quality of life with advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 39, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, H. Global Burden of Disease Study. The global, regional, and national prostate cancer burden and trends from 1990 to 2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1553747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhi, Y. Global epidemiological trends in prostate cancer burden: A comprehensive analysis from Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2025, 14, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N'DOw, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on Prostate Cancer: Planning for the Surge in Cases. Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S.K.; Pinnock, C.; Lepore, S.J.; Hughes, S.; O’Connell, D.L. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for men with prostate cancer and their partners. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, e75–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feros, D.L.; Lane, L.; Ciarrochi, J.; Blackledge, J.T. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for improving the lives of cancer patients: A preliminary study. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, J.; Bahnson, R.R.; Boston, B.; Busby, J.E.; D’Amico, A.; Eastham, J.A.; Enke, C.A.; George, D.; Horwitz, E.M.; Huben, R.P.; et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Prostate cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2010, 8, 162–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert-Williams, N.; Storey, L.; Wilson, K. Psychological interventions for patients with cancer: Psychological flexibility and the potential utility of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huggins, C.; Hodges, C.V. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1941, 1, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, E.; Srinivas, S.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Armstrong, A.J.; Bekelman, J.E.; Cheng, H.; D’Amico, A.V.; Davis, B.J.; Desai, N.; Dorff, T.; et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Prostate cancer, version 1.2021. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottet, N.; Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; De Santis, M.; Gillessen, S.; Grummet, J.; Henry, A.M.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Lame, T.B.; Mason, M.D.; et al. RCN. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer Update 2022 [Internet]. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Donovan, K.A.; Gonzalez, B.D.; Nelson, A.M.; Fishman, M.N.; Zachariah, B.; Jacobsen, P.B. Effect of androgen deprivation therapy on sexual function and bother in men with prostate cancer: A controlled comparison. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, H.I.; Halabi, S.; Tannock, I.; Morris, M.; Sternberg, C.N.; Carducci, M.A.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Higano, C.; Bubley, G.J.; Dreicer, R.; et al. Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: Recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidenfeld, J.; Samson, D.J.; Hasselblad, V.; Aronson, N.; Albertsen, P.C.; Bennett, C.L.; Wilt, T.J. Single-therapy androgen suppression in men with advanced prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 132, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, M.A.; Blumenstein, B.A.; Crawford, E.D.; Miller, G.; McLeod, D.G.; Loehrer, P.J.; Wilding, G.; Sears, K.; Culkin, D.J.; Thompson, I.M., Jr.; et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debruyne, F. Hormonal therapy of prostate cancer. Semin. Urol. Oncol. 2002, 20 (Suppl. 1), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, E.D.; Heidenreich, A.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Tombal, B.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; Mendoza-Valdes, A.; Miller, K.; Debruyne, F.M.J.; Klotz, L. Androgen-targeted therapy in men with prostate cancer: Evolving practice and future considerations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvenbag, G.J.; Furr, B.J.; Blackledge, G.R. Receptor affinity and potency of nonsteroidal antiandrogens: Translation of preclinical findings into clinical activity. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1998, 1, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. ENZAMET Trial Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Shore, N.; Tammela, T.L.; Ulys, A.; Vjaters, E.; Polyakov, S.; Jievaltas, M.; Luz, M.; Alekseev, B.; Kuss, I.; et al. ARAMIS Investigators. Darolutamide in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Given, R.; Juárez Soto, Á.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. TITAN Investigators. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, T.M.; Armstrong, A.J.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Loriot, Y.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carles, J.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. PREVAIL Investigators. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.J.; Smith, M.R.; de Bono, J.S.; Molina, A.; Logothetis, C.J.; de Souza, P.; Fizazi, K.; Mainwaring, P.; Piulats, J.M.; Ng, S.; et al. COU-AA-302 Investigators. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; de Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. AFFIRM Investigators. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Saad, F.; Chowdhury, S.; Oudard, S.; Hadaschik, B.A.; Graff, J.N.; Olmos, D.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Lee, J.Y.; Uemura, H.; et al. SPARTAN Investigators. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Azad, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Iguchi, T.; Shore, N.D.; et al. ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Murphy, L.; Clarke, N.W.; Cross, W.; Jones, R.J.; Parker, C.C.; Gillessen, S.; Cook, A.; Brawley, C.; Amos, C.L.; et al. Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy (STAMPEDE) investigators. Abiraterone acetate and prednisolone with or without enzalutamide for high-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of primary results from two randomised controlled phase 3 trials of the STAMPEDE platform protocol. Lancet 2022, 399, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorovic, A.; So, A.I.; Serag, H.; French, C.; Hamilton, R.J.; Izard, J.P.; Nayak, J.G.; Pouliot, F.; Saad, F.; Shayegan, B.; et al. Canadian Urological Association guideline on androgen deprivation therapy: Adverse events and management strategies. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2021, 15, E307–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrgidis, N.; Vakalopoulos, I.; Sountoulides, P. Endocrine consequences of treatment with the new androgen receptor axis-targeted agents for advanced prostate cancer. Hormones 2021, 20, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucci, M.; Leone, G.; Buttigliero, C.; Zichi, C.; Di Stefano, R.F.; Pignataro, D.; Vignani, F.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Di Maio, M. Hormonal treatment and quality of life of prostate cancer patients: New evidence. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2018, 70, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higano, C.S. Management of bone loss in men with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2003, 170 Pt 2, S59–S63, discussion S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.E.; Leslie, W.D.; Czaykowski, P.; Gingerich, J.; Geirnaert, M.; Lau, Y.K. A comprehensive bone-health management approach for men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2011, 18, e163–e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lim, W.; Ridge, C.A.; Nicholson, A.G.; Mirsadraee, S. The 8th lung cancer TNM classification and clinical staging system: Review of the changes and clinical implications. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2018, 8, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnea-Nita, R.-A.; Rebegea, L.-F.; Nechifor, A.; Mareș, C.; Toma, R.-V.; Stoian, A.-R.; Ciuhu, A.-N.; Andronache, L.-F.; Constantin, G.B.; Rahnea-Nita, G. The Complexity of Treatments and the Multidisciplinary Team—A Rare Case of Long-Term Progression—Free Survival in Prostate Cancer until Development of Liver and Brain Metastases. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nave, O. A mathematical model for treatment using chemo-immunotherapy. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnea-Nita, R.A.; Stoian, A.R.; Anghel, R.M.; Rebegea, L.F.; Ciuhu, A.N.; Bacinschi, X.E.; Zgura, A.F.; Trifanescu, O.G.; Toma, R.V.; Constantin, G.B.; et al. The Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Long-Term Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Associated with the Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH). Life 2023, 13, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Filippi, S.; Comelio, P.; Bianchi, N.; Frizza, F.; Dicuio, M.; Rastrelli, G.; Concetti, S.; Sforza, A.; Vignozzi, L.; et al. Sexual function in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2021, 33, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Woo, H.H.; Turner, S.; Leong, E.; Jackson, M.; Spry, N. The influence of testosterone suppression and recovery on sexual function in men with prostate cancer: Observations from a prospective study in men undergoing intermittent androgen suppression. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 2162–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, E.; Wassersug, R.J.; Robinson, J.W.; Matthew, A.; McLeod, D.; Walker, L. How Are Patients with Prostate Cancer Managing Androgen Deprivation Therapy Side Effects? Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 34, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, S.; Sooriyamoorthy, T. Erectile dysfunction. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562253/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- White, I.D.; Wilson, J.; Aslet, P.; Baxter, A.B.; Birtle, A.; Challacombe, B.; Coe, J.; Grover, L.; Payne, H.; Russell, S.; et al. Development of UK guidance on the management of erectile dysfunction resulting from radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health, 28–31 January 2002, Geneva; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Saini, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Mathur, R.; Dwivedi, S.; Saxena, A. Sexual satisfaction and partner distress in couples facing prostate cancer: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Brunckhorst, O.; Hashemi, S.; Martin, A.; George, G.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Dasgupta, P.; Stewart, R.; Ahmed, K. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality in prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Enhancing psychological flexibility in couples coping with prostate cancer: A targeted intervention model. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2025, 29, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, C.J.; Lee, K.; Kissane, D.W.; Schover, L.R.; Heiman, J.R.; Mulhall, J.P. Acceptance and commitment therapy for enhancing adherence to penile injection therapy following radical prostatectomy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Luo, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Effectiveness for Fear of Cancer Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 76, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S.; Love, A.; Macvean, M.; Duchesne, G.; Couper, J.; Kissane, D. Psychological adjustment of men with prostate cancer: A review of the literature. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2007, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sexual Side Effects | Other Systemic Side Effects |

|---|---|

| Erectile dysfunction (ED) | Hot flushes |

| Low libido | Loss of bone mineral density/loss of muscle mass/sarcopenia |

| Penis shrinkage | Cardiovascular effects/dyslipidemia |

| Testicular atrophy | Psychiatric disorders/cognitive disorders |

| Hypogonadism | Weight gain/gynecomastia |

| Delayed orgasm/anorgasmia | Decreased energy/tiredness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mihalcia Ailene, D.; Rahnea-Nita, G.; Nechifor, A.; Andronache, L.F.; Dumitru, M.E.; Rebegea, A.-M.; Stefanescu, C.; Rahnea-Nita, R.-A.; Rebegea, L.-F. Psychological Involvement in the Journey of a Patient with Localized Prostate Cancer—From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diseases 2025, 13, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100319

Mihalcia Ailene D, Rahnea-Nita G, Nechifor A, Andronache LF, Dumitru ME, Rebegea A-M, Stefanescu C, Rahnea-Nita R-A, Rebegea L-F. Psychological Involvement in the Journey of a Patient with Localized Prostate Cancer—From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diseases. 2025; 13(10):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100319

Chicago/Turabian StyleMihalcia Ailene, Daniela, Gabriela Rahnea-Nita, Alexandru Nechifor, Liliana Florina Andronache, Mihaela Emilia Dumitru, Alexandru-Mihai Rebegea, Cristina Stefanescu, Roxana-Andreea Rahnea-Nita, and Laura-Florentina Rebegea. 2025. "Psychological Involvement in the Journey of a Patient with Localized Prostate Cancer—From Diagnosis to Treatment" Diseases 13, no. 10: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100319

APA StyleMihalcia Ailene, D., Rahnea-Nita, G., Nechifor, A., Andronache, L. F., Dumitru, M. E., Rebegea, A.-M., Stefanescu, C., Rahnea-Nita, R.-A., & Rebegea, L.-F. (2025). Psychological Involvement in the Journey of a Patient with Localized Prostate Cancer—From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diseases, 13(10), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100319