COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Risk of Anxiety and Depression among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural West Bengal, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

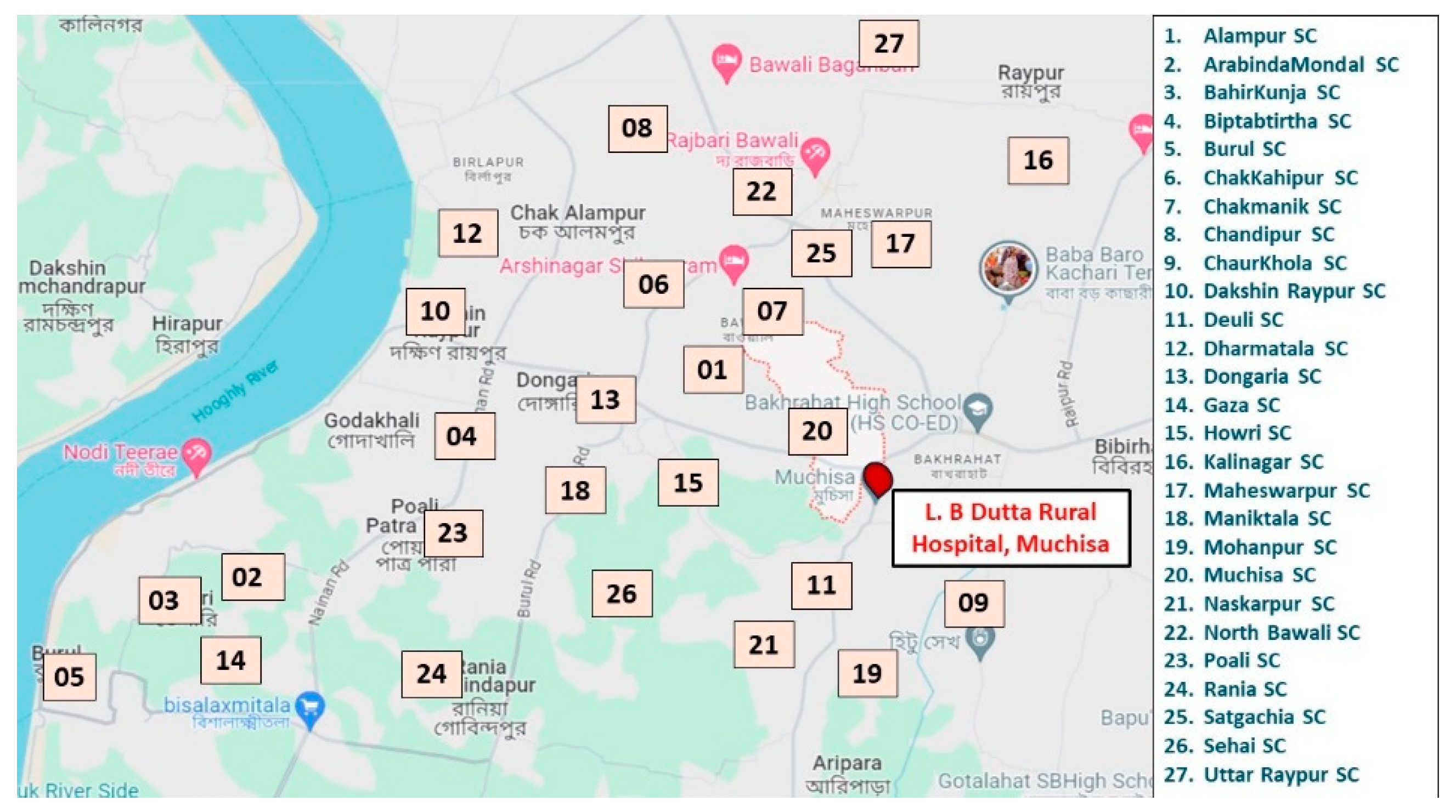

2.1. Study Population and Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Sample Size Estimation

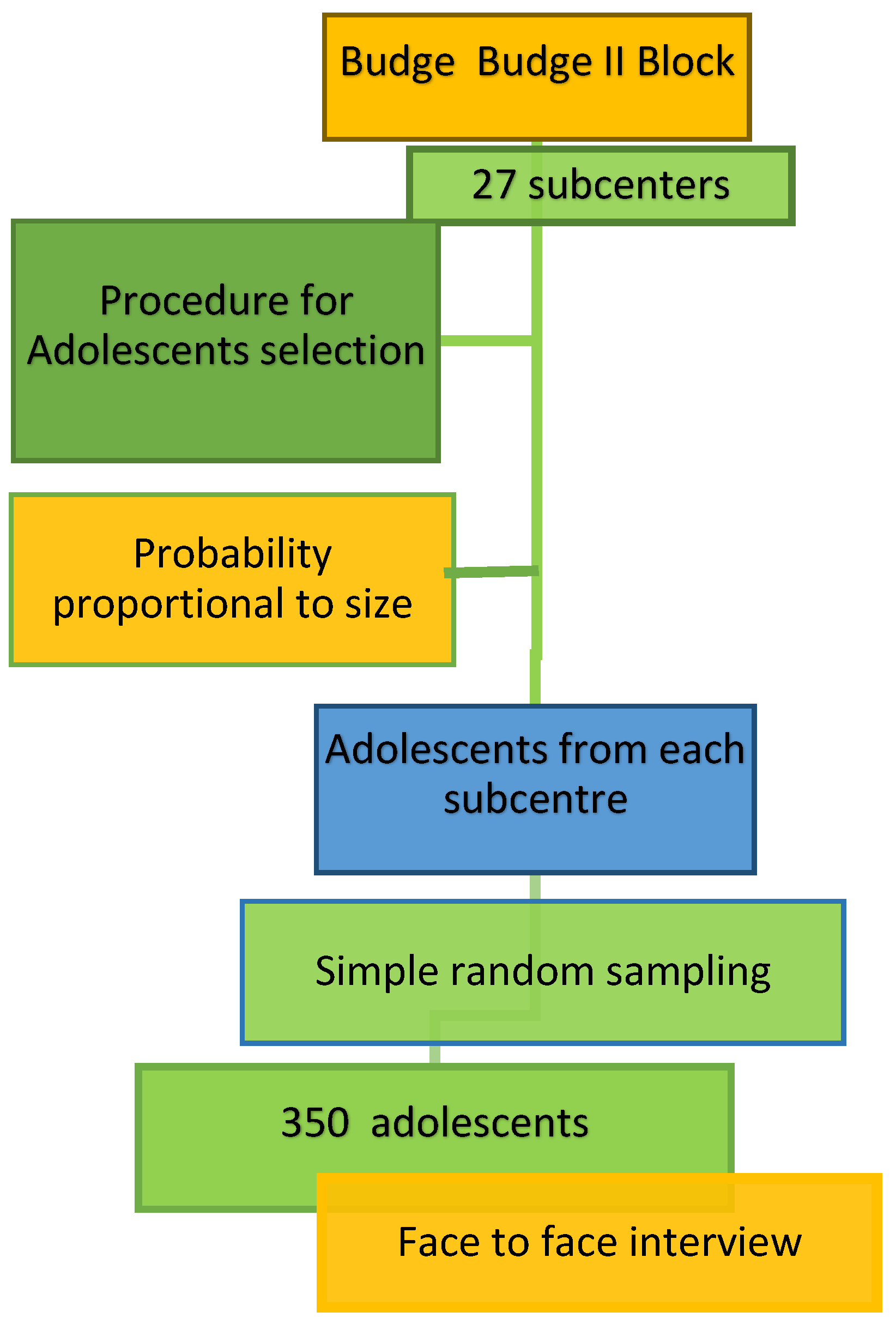

2.4. Sampling Technique

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Study Tools and Techniques

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. COVID-19 and General Health

3.2. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression

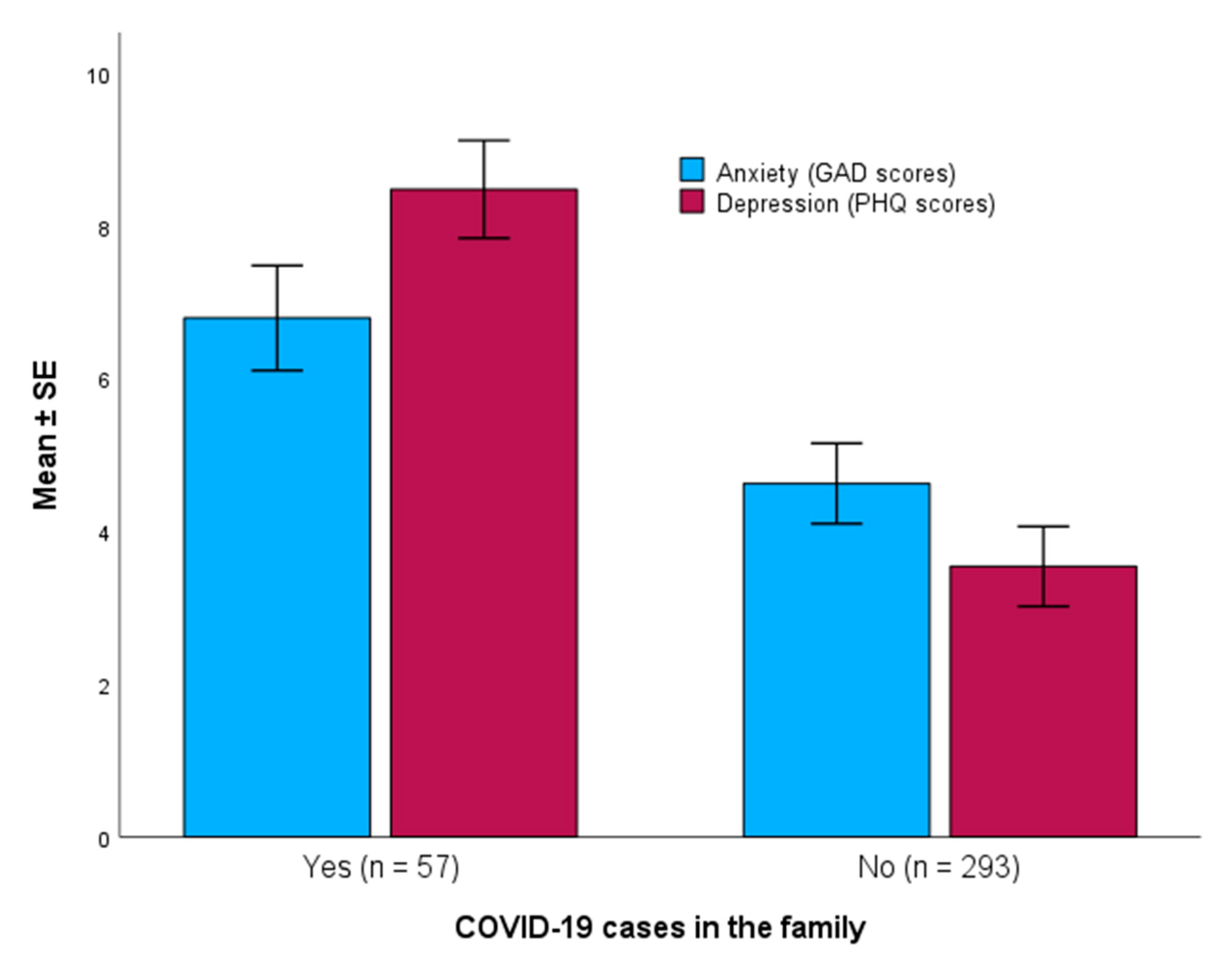

3.3. Association between COVID-19 Cases in the Family with Anxiety and Depression

3.4. Association between COVID-19 Death in the Family with Anxiety and Depression

3.5. Association between Anxiety and Depression with Demographic Variables and COVID-19

3.6. Multivariate Analysis of the Predictors of Anxiety

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents

4.2. Gender Differences

4.3. Determinants of Anxiety and Depression

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Families: Encourage open communication to facilitate healthy decision-making and provide supervision to prevent antisocial activities.

- Schools: Develop and implement specific training modules to help students cope with emergencies and their aftermath. Train teachers and staff to build a safe and supportive environment.

- Healthcare providers: Clinicians and nurses can provide coaching and counseling and educate students on self-care and coping skills. Community-based health workers should be trained to provide early interventions for adolescent mental health and encourage positive parenting practices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- GAD-7 Anxiety Scale

| Over the Last 2 Weeks, How Often Have You Been Bothered by Any of the Following Problems? | NOT AT ALL | SEVERAL DAYS | MORE THAN HALF THE DAYS | NEARLY EVERY DAY | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| Total Score: __________ | |||||||

| |||||||

| Not difficult at all ○ 0 | Somewhat difficult ○ 1 | Very difficult ○ 2 | Extremely difficult ○ 3 | ||||

Appendix B

- PHQ-9 Depression Scale

| Over the Last 2 Weeks, How Often Have You Been Bothered by Any of the Following Problems? | NOT AT ALL | SEVERAL DAYS | MORE THAN HALF THE DAYS | NEARLY EVERY DAY | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| ○ 0 | ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | |||

| Total Score: __________ | |||||||

| |||||||

| Not difficult at all ○ 0 | Somewhat difficult ○ 1 | Very difficult ○ 2 | Extremely difficult ○ 3 | ||||

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Zhang, Z.; Mitra, A.K.; Schroeder, J.A.; Zhang, L. The prevalence of and trend in drug use among adolescents in Mississippi and the United States: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) 2001–2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld, M.R.; Torregrossa, M.M. Consequences of adolescent drug use. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Bhattad, D. Immediate and short-term prevalence of depression in COVID-19 patients and its correlation with continued symptoms experience. Indian J. Psychiatry 2022, 64, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Worldometer. COVID-Coronavirus Statistics. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. New Surgeon General Advisory Raises Alarm about the Devastating Impact of the Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation in the United States. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/03/new-surgeon-general-advisory-raises-alarm-about-devastating-impact-epidemic-loneliness-isolation-united-states.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Ornell, F.; Schuch, J.B.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahia, I.V.; Blazer, D.G.; Smith, G.S.; Karp, J.F.; Steffens, D.C.; Forester, B.P.; Tampi, R.; Agronin, M.; Jeste, D.V.; Reynolds, C.F., III. COVID-19, mental health and aging: A need for new knowledge to bridge science and service. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavira, D.A.; Ponting, C.; Ramos, G. The impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health and treatment considerations. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 157, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, B.; Lyne, J.; McNicholas, F. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health in the Southeast Asia Region. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Balarajan, Y.; Selvaraj, S.; Subramanian, S.V. Health care and equity in India. Lancet 2011, 377, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.M.; Karpaga, P.P.; Panigrahi, S.K.; Raj, U.; Pathak, V.K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent health in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5484–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Roy, D.; Sinha, K.; Parveen, S.; Sharma, G.; Joshi, G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, S.; Dorji, N.; Kar, S.; Maria Sunny, A.; Deb, S.; Ghosh, S.; Chakraborty, S. COVID-19 and stress of Indian youth: An association with background, on-line mode of teaching, resilience and hope. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 12, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 10th ed.; Danielle, W.W., Cross, C.L., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; 192p. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Levis, B.; Riehm, K.E.; Saadat, N.; Levis, A.W.; Azar, M.; Rice, D.B.; Krishnan, A.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. The accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 algorithm for screening to detect major depression: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D.; McMillan, D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelani, A.; Dkhar, S.A.; Quansar, R.; Khan, S.M.S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among school-going adolescents in Indian Kashmir valley during COVID-19 pandemic. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.; Carducci, B.; Klein, J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e010713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Noh, Y.; Seo, J.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kim, M.H.; Won, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Adolescent Students in Daegu, Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Drakos, A.; Zuo, Q.K.; Huang, E. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.J.; Zhang, L.G.; Wang, L.L.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, J.C.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.X. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seedat, S.; Scott, K.M.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Berglund, P.; Bromet, E.J.; Brugha, T.S.; Demyttenaere, K.; De Girolamo, G.; Haro, J.M.; Jin, R.; et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009, 66, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Gillham, J.E.; Seligman, M.E. Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2009, 29, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, H.; Richards, M.; Yang, S.; Liang, H.; Chen, X.; Fu, C. Study problems and depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: Poor parent-child relationship as a vulnerability. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, W.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.T. Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhai, A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, C.; Duan, S.; Zhou, C. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in Shandong Province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 570096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 15.59 ± 1.93 | |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 182 (52) | |

| Female | 168 (48) | |

| Number of family members, mean ± SD (range) | 5.0 ± 0.7 (4–7) | |

| Family income (Rupees) (1 US $ = 83.95 Rupees; n = 349) | ||

| <25,000 | 136 (39.0) | |

| 25,000–50,000 | 156 (44.7) | |

| 50,001–90,000 | 46 (13.2) | |

| ≥90,001 | 11 (3.2) | |

| Smoking habit of the participant | ||

| Current smoker | 9 (2.6) | |

| Occasional | 12 (3.4) | |

| Never smoked | 329 (94.0) | |

| Family history of COVID-19 | ||

| Did anybody have COVID-19 (Yes) | 57 (16.3) | |

| Did anybody die of COVID-19 in your family (Yes) | 8 (2.3) | |

| Did you suffer from COVID-19 (Yes) | 5 (1.4) | |

| Are you currently having any symptoms (Yes) | 27 (7.7) | |

| Do you have symptoms of anxiety or depression (such as feeling sad or anxious, feeling easily frustrated or restless, having trouble sleeping, or others) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Who did you consult for your current illnesses (n = 27) | ||

| Qualified medical doctor | 4 (14.8) | |

| Pharmacy medicine seller | 16 (59.3) | |

| Self-medication | 4 (14.8) | |

| None | 3 (11.1) | |

| How do you rate your current health (n = 326) | ||

| Very good | 287 (88.0) | |

| Good or moderate | 31 (9.5) | |

| Bad or very bad | 8 (2.5) | |

| GAD Categories | Total | Male | Female | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (0–4) | 225 (64.3) | 145 (79.7) | 80 (47.6) | <0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 47 (13.4) | 28 (15.4) | 19 (11.3) | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 67 (19.1) | 3 (1.6) | 64 (38.1) | |

| Severe (≥15) | 11 (3.1) | 6 (3.3) | 5 (3.0) | |

| Total | 350 (100) | 182 (100) | 168 (100) |

| PHQ Categories | Total | Male | Female | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None to Minimal (0–4) | 245 (70.0) | 145 (79.7) | 100 (59.5) | <0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 53 (15.1) | 28 (15.4) | 25 (14.9) | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 44 (12.6) | 3 (1.6) | 41 (24.4) | |

| Moderately Severe (15–19) | 7 (2.0) | 5 (2.7) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Severe (20–27) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 350 (100) | 182 (100) | 168 (100) |

| Variable | Male (n = 182) | Female (n = 168) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score: Median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 5 (3–12) | <0.001 |

| Depression score: Median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 4 (1–10) | <0.001 |

| Age | Gender | Income Group | COVID Cases | COVID Death | Depression | Anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | 1 | 0.064 | −0.224 | 0.015 | −0.142 | −0.022 | 0.123 |

| p | 0.231 | <0.001 | 0.781 | 0.008 | 0.677 | 0.022 | ||

| n | 350 | 349 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 | ||

| Gender (male = 1; female = 2) | r | 1 | −0.127 | −0.010 | 0.070 | 0.246 | 0.376 | |

| p | 0.018 | 0.853 | 0.189 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| n | 349 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 | |||

| Income group | r | 1 | 0.098 | 0.060 | −0.272 | −0.292 | ||

| p | 0.067 | 0.265 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| n | 349 | 349 | 349 | 349 | ||||

| COVID cases | r | 1 | −0.067 | −0.399 | −0.185 | |||

| p | 0.208 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| n | 350 | 350 | 350 | |||||

| COVID death | r | 1 | −0.432 | −0.377 | ||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| n | 350 | 350 | ||||||

| Depression | r | 1 | 0.856 | |||||

| p | <0.001 | |||||||

| n | 350 | |||||||

| Anxiety | 1 | |||||||

| Independent Variable | β-Coefficient | SE | p-Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| (Constant) | 29.32 | 2.68 | |||

| COVID death in the family (1 = yes, 2 = no) | −11.68 | 1.23 | <0.001 | −14.09 | −9.27 |

| COVID cases in the family (1 = yes, 2 = no) | −2.21 | 0.50 | <0.001 | −3.18 | −1.23 |

| Gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | 3.25 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 2.53 | 3.98 |

| Income groups (Rupee) 1 | −1.12 | 0.24 | <0.001 | −1.58 | −0.65 |

| Independent Variable | β-Coefficient | SE | p-Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| (Constant) | 47.07 | 3.16 | |||

| COVID death in the family (1 = yes, 2 = no) | −14.88 | 1.19 | <0.001 | −17.22 | −12.53 |

| COVID cases in the family (1 = yes, 2 = no) | −5.04 | 0.48 | <0.001 | −5.98 | −4.10 |

| Gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | 2.38 | 0.36 | <0.001 | 1.68 | 3.08 |

| Income groups (Rupee) 1 | −1.19 | 0.23 | <0.001 | −1.65 | −0.73 |

| Age | −0.35 | 0.09 | <0.001 | −0.53 | −0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitra, A.K.; Dutta, S.; Mondal, A.; Rashid, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Risk of Anxiety and Depression among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural West Bengal, India. Diseases 2024, 12, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100233

Mitra AK, Dutta S, Mondal A, Rashid M. COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Risk of Anxiety and Depression among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural West Bengal, India. Diseases. 2024; 12(10):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100233

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitra, Amal K., Sinjita Dutta, Aparajita Mondal, and Mamunur Rashid. 2024. "COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Risk of Anxiety and Depression among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural West Bengal, India" Diseases 12, no. 10: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100233

APA StyleMitra, A. K., Dutta, S., Mondal, A., & Rashid, M. (2024). COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Risk of Anxiety and Depression among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural West Bengal, India. Diseases, 12(10), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100233