1. Introduction

As one of the implementation carriers of intelligent manufacturing systems, industrial robots are gradually becoming the core component of intelligent production lines. Compared with traditional human operation, modern industrial robots have higher precision, stronger adaptability, and wider application fields. They play an irreplaceable role in various industrial scenarios such as assembly, welding, and handling, greatly improving production efficiency and reducing labor costs. Multi-robot assembly is an important application scenario in intelligent manufacturing. Multiple robots can work together to complete complex assembly tasks, which solves the problem of low efficiency caused by manual operation in high-precision scenes to a certain extent.

To complete the assembly task efficiently and safely, we must pay attention to the problem of the robot compliance control. Compliance control of robot refers to the dynamic adjustment of the motion state of the robot under certain perceptual feedback conditions, to improve the interaction ability of the robot in performing tasks and the adaptability to uncertain interference. In general, the compliance control of robots can be divided into two categories: passive compliance [

1,

2,

3] and active compliance [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Passive compliance usually refers to the design of mechanical devices to achieve compliance with the environment. Active compliance relies on control strategies and algorithms to dynamically adjust the state variables of the robot to adapt to sudden environmental changes.

At present, most of the research is to achieve active compliance control through force sensing feedback. There are two widely developed force control algorithms, which are force/position hybrid control [

9] and impedance control [

10]. The impedance control method models the robot as a second-order system with mass-damping-spring properties, to establish the dynamic relationship between the force deviation and the position deviation of the system.

Figure 1 is the control block diagram of motion-based impedance control (hereinafter referred to as admittance control). The control structure is composed of a force control external loop and a position control internal loop, which realizes the mapping from generalized force to generalized position. At the same time, admittance control does not require the dynamic model of the robot. These characteristics make it more convenient for engineering applications.

Liu et al. [

11] used visual methods to identify the posture of components and realize the assembly of building components. Hu et al. [

12] designed an adaptive variable impedance controller to realize the stone slab installation task on the wall by carrying the dual-arm robots on the mobile platform. In Wang et al. [

13], a passive compliance device was designed. Based on the characteristics of the device, a pin-in-hole strategy was designed so that no force sensor was required. However, this method still has challenges in the application of pin-in-hole assembly with complex shapes. In Park et al. [

14], a control method was designed without a force sensor for robot shaft hole assembly. By estimating the contact conditions, the compliant control of the assembly process was realized. The effect of this method is usually highly related to the accuracy of the model.

Zhou et al. [

15] used a force/position hybrid control algorithm to reduce the impact of the algorithm when switching between free space and constrained space by estimating the initial position and direction of the threaded hole. In Shen et al. [

16], the visual system based on P2HNet is used that can identify more complex shapes to cooperate with spiral search to realize the peg-in-hole assembly with irregular cross section. However, the intelligent control method combined with machine learning is more uncertain than traditional control. In Zhao et al. [

17], by using the reversible dynamic movement primitives method, combined with the compliance control to optimize the trajectory, the force of the shaft hole assembly process is reduced. In Liu et al. [

18], a screw motion strategy was designed to reduce the axial friction of the peg-in-hole assembly.

The above research method shows the key and difficult points of the assembly system, i.e., the alignment problem between the assembly parts and the compliance of the system to the force during assembly. For the alignment problem, the existing main solution is to use the visual system for error compensation, but the normal operation of the visual system is inseparable from the suitable light source environment, and it brings cost problems to the design. For the problem of force control in the assembly process, most of the existing methods use active compliance methods or do not consider them. In addition, the addition of the dual robot system also brings more flexibility to the assembly system. However, the related methods do not take these problems into account at the same time. In this paper, a dual-arm robot’s threaded assembly system is designed. The system does not use a visual method, but uses force sensors to estimate the relative position of two workpieces. At the same time, the sensor is also responsible for sensing the force of assembly and the external environmental force of the system during the assembly process. In this paper, the assembly process of the thread is segmented, and a phased controller is designed based on this, so that the system not only pays attention to the force of assembly, but also adapts to the force of the external environment.

2. Related Work

2.1. Admittance Control Principle

In the classical theory of admittance control [

10], in Cartesian space, the admittance model of the robot is a second-order system. Assuming that the position controller can completely track the corrected trajectory, the admittance relationship is as follows:

Among them, are the virtual positive definite mass matrix, damping coefficient matrix, and stiffness coefficient matrix of the system. are the reference trajectory and the modified trajectory (which is also the actual trajectory), and are their velocity and acceleration, respectively. is the actual contact force/torque, is the expected contact force/torque.

2.2. Task Object Modeling

The assembly workpiece is modeled as a threaded connector, as shown in

Figure 2. They are external thread workpieces and internal thread workpieces, respectively. Without loss of generality, it is simplified as a workpiece with uniform mass distribution in the radial direction. According to the description in reference [

19], the tightening torque

T of thread pretension is composed of thread friction torque

and bearing surface friction torque

as follows:

Equation (

1) References from Reference [

19].

is the lead angle,

F is the axial preload, and

is the bearing surface friction diameter of the contact surface.

and

are the friction coefficients of the bearing surface and thread respectively.

In this paper, the thread assembly process is divided into three stages: grasping, alignment, and tightening. Since the workpiece has a central symmetry in the radial direction, it can be assumed that the axes of the two components are in the same plane, thus simplifying the three-dimensional assembly into a two-dimensional plane assembly process. The simplified assembly process can be represented as

Figure 3.

The key to the success of thread assembly has two parts. The first is whether the workpieces can be correctly aligned, which is the premise of the correct fit of the thread. If it cannot be aligned, it may cause the internal and external threads to be unable to mesh. If the tightening direction is not perpendicular to the axial direction of the workpiece during assembly, there will be a blocking phenomenon, as shown in

Figure 4, resulting in thread locking.

Secondly, the tightening torque needs to be controlled when the thread is tightened, especially for some brittle workpieces; the tightening needs to be completed within the specified tightening torque range. In addition, the slow rotation of the workpiece should be controlled when the workpieces are aligned to avoid excessive torque damage to the workpiece when the blocking occurs.

2.3. Dual Robot System Modeling

The kinematics modeling of the dual-robot system is shown in

Figure 5.

,

represent the workpiece coordinate system fixed at the center of mass

of the workpiece.

,

represent the

i-th axis coordinate system of the left and right robots;

and

are the tool coordinate system of the robots;

and

represent the base coordinate system of the robots; and

is the world coordinate system.

and

describe the transformation matrix of the dual-robot tool coordinate system for the base coordinate system.

In this paper, UR series robots are used. The DH parameters of this series of robots are known (see the part of the corresponding model product in the official DH parameter support file), and the distribution of joint links is shown in

Figure 6. According to the DH modeling method, the transformation matrices

and

from the base coordinate system of each robot to the sixth joint coordinate system of each robot are obtained:

The motion trajectory of each workpiece can be described as the trajectory of the workpiece coordinate system

relative to the world coordinate system

, which can be obtained by the following Equation (

3):

3. Design of Dual Robot Cooperative Control System

The flow chart of the dual-robot cooperative control algorithm is shown in

Figure 7. The whole system is mainly composed of five core modules: assembly strategy module, data processing module, admittance control module, dual-robot cooperative module, and stepper motor control module.

Among them, the assembly strategy module is equipped with a set task flow framework, and the data processing module is responsible for decomposing and calculating the expected driving force of each robot according to the real-time feedback force sensor value. The admittance module is responsible for maintaining the flexibility of the assembly process according to the actual force. The dual-robot cooperation module decomposes the expected assembly trajectory and expected assembly force of the workpiece, and combines the intelligent admittance module to calculate the real trajectory information of the dual robot in each assembly stage. The stepper motor control module provides tightening torque during the workpiece tightening process.

3.1. Design of Dual Robot Controller for Grasping and Alignment Stage

The control block diagram of the workpiece grasping and alignment stage is shown in

Figure 8. There is no collision between the robots in the grasping stage, which is free movement. The robots grab workpieces, respectively, through trajectory

and

.

In the alignment stage, the two workpiece ends will collide. In this paper, an asymmetric dual-robot compliance controller is proposed: the right robot shows rigidity to the collision, while the left robot shows flexibility to the collision. For the right robot, only the closed-loop position control is performed. For the left robot, the admittance control is used for compliant control to compensate for the end face distance error between the workpieces (reserved distance to adapt to different types of workpieces). Based on the assumption of Equation (

4), there is the following:

is the reference trajectory of the left robot, is the value of the left force sensor, is the expected contact force between the workpieces, and is the robot trajectory corrected by admittance control until the contact force of the two workpieces reaches , The left robot stops axially approaching the right robot.

When the contact force is generated, the values

and

of the two sensors can be read. By calculating the generated torque, it is judged whether the axial equivalent assembly force of the workpiece coincides with the axis of the workpiece, to determine whether the workpiece is aligned, as shown in

Figure 9.

If the alignment is not completed, the arm will always exist.

Figure 9 shows that when the end faces of the workpieces are in contact, the workpiece is subjected to the axial extrusion force imposed by the other side and produces a torque. It can be seen from the diagram that the axial distance between the workpieces is equal to half of the difference between the force arms of the equivalent force points of the workpieces. The X and Y axis torque values of the force sensor can be obtained by the following formula:

are the torque values of each sensor in the X and Y axes, , are the components of the friction force generated by contact in the X and Y directions. If are known, the shaft spacing can be obtained as , which is compensated as an error to obtain the corrected trajectory of the right robot on the tangent plane. When the shaft spacing is small enough, the internal thread workpiece enters the chamfer of the external thread workpiece. At this time, the flexibility of the right robot in the position can compensate for the remaining coaxiality error.

After admittance compensation and shaft spacing compensation,

can be expressed as follows:

is also input into the robot in the form of joint angle through the closed-loop position controller.

3.2. Design of Controller in Tightening Stage

In the tightening stage, the thread assembly has been partially connected, and there is indirect coupling between the ends of the robot [

20]. The system control block diagram is shown in

Figure 10. At this time, we design the external loop compliance control of the closed chain system for the contact force of the external environment. That is, it is necessary to reflect the flexibility of the unknown external environmental interference, but also to reflect the flexibility of the workpiece assembly process.

is regarded as the centroid trajectory moving due to thread meshing. If the assembly is regarded as a whole, when the external environment acts on it, the two robots will produce a modified trajectory that conforms to the external force. Furthermore, the force control is divided into the external loop force control for the environmental force and the internal loop force control for the assembly force.

For the thread meshing process, the two mutually engaged workpieces should meet the thread meshing constraint conditions shown in Equation (

8):

Thread tightening begins at . represents the homogeneous transformation matrix between the right robot and the left robot’s tool coordinate system. is the expression of the origin of the left robot tool coordinate system in the right robot tool coordinate system, represents the thread pitch, and represents the angular velocity in the screwing direction of the thread. represents the relative rotation between the two robot tools when the thread is engaged.

Under the condition that

s determined, the trajectory of the right robot can be obtained as follows:

Then the trajectory of the left robot is obtained by combining the inherent constraints

of the thread meshing in the following Equation (

8):

Figure 11 is the schematic diagram of the workpiece force in the tightening process. Where

is the assembly internal force equivalent to the center of mass. The external force

comes from the environment. And after it is equivalent to the center of mass,

can be obtained.

,

are set of forces applied by the dual robots.

The distance between the center of mass and the grasping point of the robot is set to be

, and

is the antisymmetric matrix of

. According to Newton’s second law of motion, the resultant force formula of the workpiece can be obtained. Since the movement of the system is slow, the acceleration is approximately zero.

and

can be obtained by the sensor. Therefore, the internal force and external force can be decoupled from the actual force as follows:

The obtained internal and external force values flow into the internal and external force control loops, respectively, and the compliance control of the system relative to the environmental force and relative to the workpiece force is carried out.

As shown in

Figure 10,

and

first enter the external loop admittance controller. By decomposing the measured value of the sensor to obtain the external force

, we can obtain the following:

For the right robot, the trajectory corrected by the external loop admittance will flow directly into the position controller. For the left robot, compliance control of the internal forces is still required to provide the axial preload as follows:

4. Simulation Experiment

Matlab R2022b is used for simulation verification, and Matlab Robotic Toolbox is used for visual demonstration. In the simulation, UR10e and UR16e are used to build a dual robot system. The external force sensor at the end of the robot is connected to the two-finger gripper. The task target is designed as the assembly of a pair of M48 threaded tubes. To simplify the simulation, the thread meshing process is simplified into a fixed speed shaft-in-hole process. The task scene is shown in

Figure 12. The left robot is UR16e, which grabs the external thread workpiece; the right robot is UR10e, grabbing the internal thread workpiece.

In the task, there is an initial distance between the workpieces, and the axes of the workpieces do not coincide. The expected assembly force is set to be in the Z direction of the sensor coordinate system, the expected environmental contact force is 0 N, the two forces in different directions, and the possible torque caused by their offset will eventually be decoupled into six-dimensional force/torque in the sensor. The allowable error of alignment is 0.001 m. The admittance coefficient matrix needs to be designed as a symmetric positive definite matrix to ensure the stability of the system.

The simulation takes 5.76 s. Among them, at 3.66–3.91 s, a vertical downward environmental constant force Fe = −80 N is applied at the entity with an offset of 0.5 m from the center of mass of the workpiece.

Figure 13 shows the assembly process. In the simulation, the grasping process of the workpiece is omitted, and the aligning and tightening processes are demonstrated.

Figure 13a–c represent the alignment process of the workpiece. It is assumed that there is an axis spacing in the Z direction between the robots due to the position tracking error of the robot. UR16e is first close to UR10e, and contact force is generated. At this time, the distance between the axes of the robots can be calculated by the force arm, to correct it.

Figure 13d–h shows the tightening process of the workpiece. Among them,

Figure 13e–g is the trajectory correction of the dual robot in response to the external force when the external force of the environment is generated.

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the trajectory of the dual robot end in the world coordinate system and the contact force between the workpieces during the task. It can be seen from the figure that the workpieces are in contact at 2.12 s, resulting in contact force. Under the control of the internal loop admittance algorithm, the force quickly converges to the expected value. At the same time, the workpiece starts to align, the shaft spacing error is continuously corrected, and the alignment is completed at 2.67 s. After the alignment condition is satisfied, the workpiece starts the thread meshing with a length of 0.006 m with −5 N as the desired axial assembly force. In the process of thread tightening, due to the inherent constraints of meshing, the assembly force will not change significantly.

Figure 16 is the torque diagram generated by the external force at the two contact points during the thread tightening process. In the simulation, the offset external force is equivalent to the center of mass of the workpiece, and then Equation (

11) is used to determine the force and moment of the external force at the center of mass equivalent to the action point of the robots. The force and torque are adaptively controlled by the external loop admittance algorithm. It can be seen from

Figure 14 that at 3.65–3.9 s, the dual robots have different degrees of deviation in the Z and X directions of the world coordinate system.

Figure 17 shows the torque change detected when the thread is preloaded. According to Equation (

1), the tightening torque can be determined by the axial preload, i.e., the axial assembly force and other parameters. When the Z axis torque of the sensor is detected to be greater than the expected tightening torque, the signal is emitted. At this time, the stepper motor is controlled to turn over a specific angle [

21], and the thread is tightened.

5. Experiment

As shown in

Figure 18, the UR robots are used to build the platform of the dual robot cooperative assembly system. The right robot is UR10e, and the left robot is UR16e. Due to the external tightening device, the actuator of the UR16e does not coincide with the axis of the robot body. In addition to thread alignment, the robot is also responsible for generating tightening torque.

The workpiece to be assembled is set as a certain type of thread model, which is similar to the simulation, and the thread length is 5 mm. In practical applications, due to the existence of interference and noise, as well as the inherent accuracy of the equipment, we only limit the index to the maximum allowable value of the project. The allowable error of alignment is set to 1 mm. In order not to damage the workpiece model, the expected contact force in the Z direction is set to be −4 N, and the expected tightening torque is −1 N·m. For safety reasons, no external environmental force is set in the experiment.

Firstly, the dual robot system is grasping, as shown in

Figure 19. The left robot clamps the external thread workpiece, and the right robot clamps the internal thread workpiece, and moves to the assembly site along the predetermined trajectory in a suitable pose.

Figure 20 is the pose of the end of the robot after the clamping is completed.

Figure 21 shows the process of thread alignment and tightening. The left robot first slowly approaches the right robot and produces a small misalignment that is difficult to observe by the human eye. However, the repetitive positioning accuracy of the UR robot is small enough to make the small misalignment within the allowable deviation range.

Figure 22 shows the force of UR10e in the sensor coordinate system. From

Figure 22a, at about 13.97 s, the end faces of the workpieces begin to contact, and the peak value of the generated force is −13.32 N, and then gradually returns to −4 N. After that, as the thread gradually meshed, the force in the Z direction fluctuated, with a fluctuation range of about 5.2 N, until the tightening was completed. At this time, the force in the Z direction was stable at about −4.1 N. In the process of tightening, the robot is also subjected to fluctuating force in the X and Y directions. This is due to the existence of errors in actual operation, which lead to the failure of the axis of the workpieces to be fully aligned and produce periodic force in the process of thread tightening.

It can be seen from

Figure 22b that the periodically changing contact force in each direction generates a periodically changing torque, and the extrusion force generated in the Z direction will generate torque in the X and Y axes. The torque of the Z axis is more stable, and only the tightening torque is detected when the thread is tightened. At this time, the stepper motor stopped rotating, so that the torque stays within the established range, and the maximum Z-axis torque value detected is −1.02 N·m.

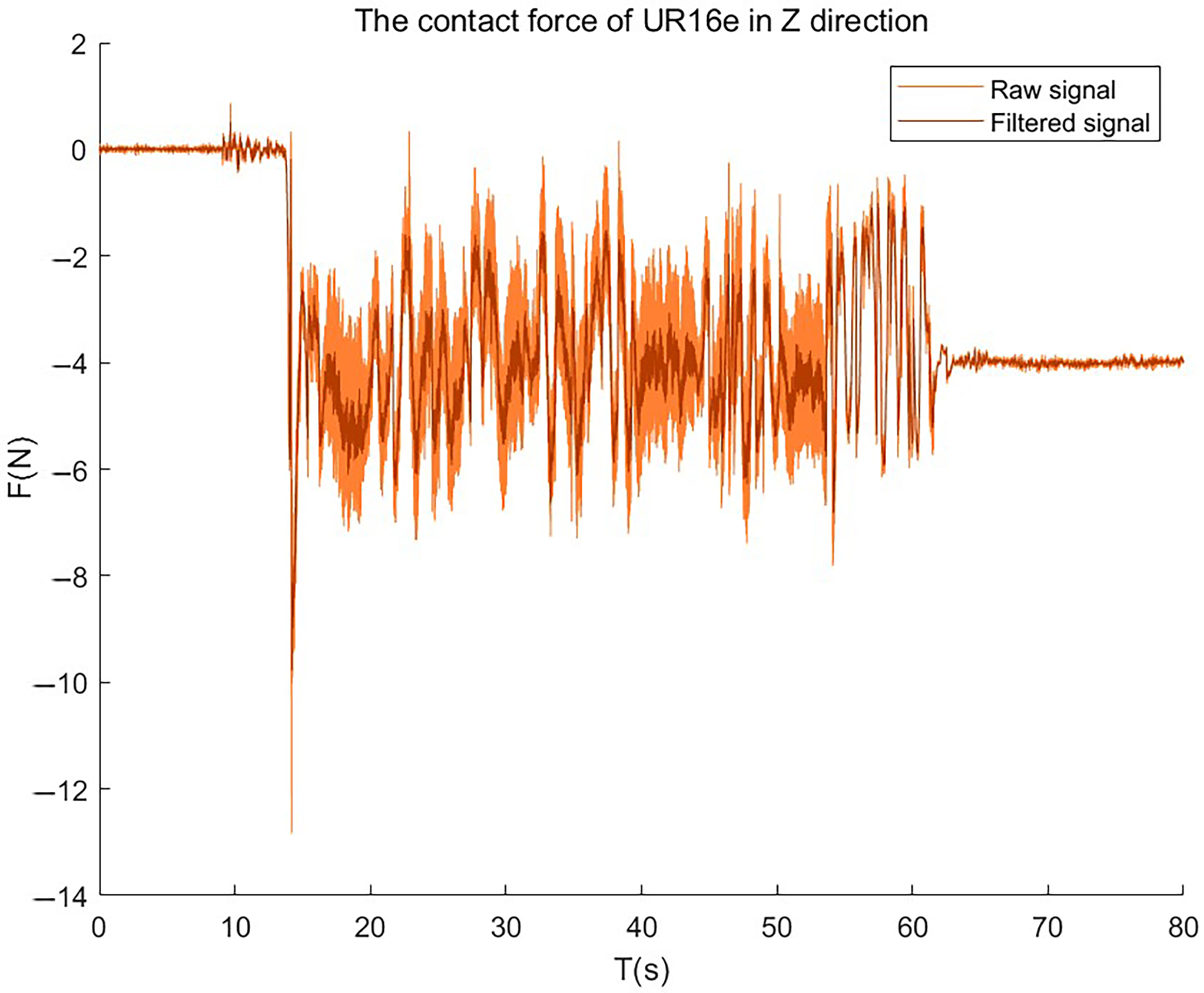

Figure 23 shows the force of UR16e in the sensor coordinate system. Since the UR16e motion brings a small vibration, the overall vibration of its measured value is significantly larger than that of the UR10e. To reduce the influence of force error caused by vibration, it is necessary to filter the measured value of the UR16e end sensor.

Figure 24 shows the effect comparison of the Z-direction force measurement value of the UR16e sensor before and after Kalman filtering.

Figure 25 shows the change of the end pose of the robots in the world coordinate system during the assembly process. It can be seen from the figure that UR16e began to approach UR10e under the action of admittance control at about 8.14 s. At about 13.97 s, the workpieces contacted and collided with each other to produce force overshoot, which caused the vibration of the end in the Y direction.

Subsequently, the robot tracked the expected contact force within 1 s and tested the coaxiality of the workpieces within the allowable error range, marking the completion of the alignment phase. Then, enter the tightening phase. After the tightening is completed, the stepper motor stops running and the task ends.

In this experiment, the dual robot system only takes about 48.54 s to complete the 5mm thread assembly task and can accurately track the assembly force in the Z direction, and its characteristics are basically in line with the simulation results. However, there are fluctuating assembly forces and moments in the X and Y directions, which are caused by the allowable error of the coaxiality of the workpieces.

In addition, the experiment shows that in the alignment stage, the excessive axis spacing between the workpieces is not an inevitable phenomenon. Different attributes such as workpiece size and weight, different experimental equipment, or accidental collision with the environment during the task may lead to a decrease in the positioning accuracy of the robot, which may affect the alignment results. At this time, the alignment algorithm is needed to compensate for the error.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a control system for thread workpiece assembly is proposed. The kinematics modeling of the dual-robot system is carried out. The thread workpiece in the meshing is regarded as the whole of the continuous movement of the center of mass. So it is proposed that the dual-robot system will experience the process of forming a closed chain from an open chain during the assembly process. Based on force feedback, a simple control algorithm is designed to realize the compliance control of workpiece alignment and assembly processes. Based on the constraints of the dual-robot closed chain system, the position change and force situation of the dual-robot cooperative work process are analyzed. The internal and external force decomposition strategy is designed for the assembly system, and then combined with the admittance control algorithm, the closed chain system can track the assembly’s internal force and adapt to the possible environmental external force interference, and an asymmetric dual robot controller is designed, so that the dual robot system is regarded as a closed chain system. The force of the robot is decomposed into assembly internal force and environmental external force by a force decomposition algorithm, so that the system can not only track the expected assembly force, but also adapt to the sudden environmental force.

The assembly simulation experiment of the M48 thread workpiece is carried out by Matlab. The simulation results show that the robots can align the workpiece by force, track the expected assembly force, and adapt to the external force of the environment. It is proved that the dual robot system has theoretical feasibility in the main task of thread assembly.

Finally, the UR10e and UR16e platforms were used for further verification. The experiment successfully completed the thread assembly task in about 48.54 s. The results verify the correctness of the simulation to a certain extent and also verify the feasibility of the scheme proposed in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.; methodology, X.H. and A.X.; software, X.H.; validation, B.J., X.H. and A.X.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L., M.Z. and X.Z.; resources, B.J.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H., A.X. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, A.X.; visualization, A.X., L.L., M.Z. and X.Z.; supervision, B.J.; funding acquisition, B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant number 20230201097GX).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tawk, C.; Sariyildiz, E.; Alici, G. Force control of a 3D printed soft gripper with built-in pneumatic touch sensing chambers. Soft Robot. 2022, 9, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Ding, H. Robotic compliant grinding of curved parts based on a designed active force-controlled end-effector with optimized series elastic component. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AboZaid, Y.A.; Aboelrayat, M.T.; Fahim, I.S.; Radwan, A.G. Soft robotic grippers: A review on technologies, materials, and applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 372, 115380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Chen, G.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, H. An adaptive robust hybrid force/position control for robot manipulators system subject to mismatched and matched disturbances. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42264–42278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, D. Adaptive variable impedance force/position hybrid control for large surface polishing. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2024, 51, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K. The improved force/position hybrid control system for multi joint humanoid multi fingered dexterous hand. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 4343–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, N.; Liu, J.; Jia, Y. Dynamic modeling and control of deformable linear objects for single-arm and dual-arm robot manipulations. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, L.; Xu, P.; Shen, Y.; Tang, Q. A task-adaptive deep reinforcement learning framework for dual-arm robot manipulation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raibert, M.H.; Craig, J.J. Hybrid position/force control of manipulators. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1981, 102, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N. Impedance control: An approach to manipulation. In Proceedings of the 1984 American Control Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–8 June 1984; pp. 304–313. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Gu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z. Automatic assembly of prefabricated components based on vision-guided robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Cao, J. Adaptive variable impedance control of dual-arm robots for slabstone installation. ISA Trans. 2022, 128, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, G.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z. A robotic peg-in-hole assembly strategy based on variable compliance center. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167534–167546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, J.; Lee, D.H.; Park, J.H.; Baeg, M.H.; Bae, J.H. Compliance-Based Robotic Peg-in-Hole Assembly Strategy without Force Feedback. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 6299–6309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Research on assembly method of threaded fasteners based on visual and force information. Processes 2023, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, R.; Huang, Z.; Chen, G. Learning-based visual servoing for high-precision peg-in-hole assembly. Actuators 2023, 12, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Ding, H. Robotic peg-in-hole assembly based on reversible dynamic movement primitives and trajectory optimization. Mechatronics 2023, 95, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Song, L.; Hou, Z.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.; Xu, J. Screw insertion method in peg-in-hole assembly for axial friction reduction. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 148313–148325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T. Bolted Joint Engineering: Fundamentals and Applications; Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, M.H.; Zhou, W.Y. Research on Industrial Robot Cooperative Control Technology for Automatic Drilling and Riveting System. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 20, 87–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Preload control method of threaded fasteners: A review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Principle diagram of admittance control.

Figure 1.

Principle diagram of admittance control.

Figure 2.

Simplified workpiece model.

Figure 2.

Simplified workpiece model.

Figure 3.

Thread assembly process. (a) Thread Gripping; (b) Thread Contact; (c) Thread Alignment; (d) Thread Tightening.

Figure 3.

Thread assembly process. (a) Thread Gripping; (b) Thread Contact; (c) Thread Alignment; (d) Thread Tightening.

Figure 5.

Dual robot open chain coordinate system distribution.

Figure 5.

Dual robot open chain coordinate system distribution.

Figure 6.

Joint-link coordinate system distribution of UR10e robot.

Figure 6.

Joint-link coordinate system distribution of UR10e robot.

Figure 7.

Flow chart of control system.

Figure 7.

Flow chart of control system.

Figure 8.

Controller for grasping and aligning stage.

Figure 8.

Controller for grasping and aligning stage.

Figure 9.

Force analysis in alignment process.

Figure 9.

Force analysis in alignment process.

Figure 10.

The controller in tightening stage.

Figure 10.

The controller in tightening stage.

Figure 11.

Force decomposition diagram of assembly process.

Figure 11.

Force decomposition diagram of assembly process.

Figure 12.

Task scenario.

Figure 12.

Task scenario.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of assembly process (a–i).

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of assembly process (a–i).

Figure 14.

The position change of the end of the dual robot.

Figure 14.

The position change of the end of the dual robot.

Figure 15.

The change of y axial contact force of robot.

Figure 15.

The change of y axial contact force of robot.

Figure 16.

The torque change caused by the external force of the two robots.

Figure 16.

The torque change caused by the external force of the two robots.

Figure 17.

Fastening torque detection.

Figure 17.

Fastening torque detection.

Figure 18.

Dual-arm Collaborative Assembly Task Site.

Figure 18.

Dual-arm Collaborative Assembly Task Site.

Figure 19.

Robots grab the workpiece.

Figure 19.

Robots grab the workpiece.

Figure 20.

Workpiece to be aligned.

Figure 20.

Workpiece to be aligned.

Figure 21.

Thread alignment and tightening process (a–d).

Figure 21.

Thread alignment and tightening process (a–d).

Figure 22.

The force change of the end of the UR10e.(a) Force conditions in the X, Y, and Z directions. (b) Moment conditions about the X, Y, and Z axes.

Figure 22.

The force change of the end of the UR10e.(a) Force conditions in the X, Y, and Z directions. (b) Moment conditions about the X, Y, and Z axes.

Figure 23.

The force change of the end of the UR16e. (a) Force conditions in the X, Y, and Z directions. (b) Moment conditions about the X, Y, and Z axes.

Figure 23.

The force change of the end of the UR16e. (a) Force conditions in the X, Y, and Z directions. (b) Moment conditions about the X, Y, and Z axes.

Figure 24.

Z-direction force filtering of UR16e.

Figure 24.

Z-direction force filtering of UR16e.

Figure 25.

Trajectory change in Y direction at the end of dual robot.

Figure 25.

Trajectory change in Y direction at the end of dual robot.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |