Research Progress and Design Considerations of High-Speed Current-Mode Driver ICs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background and Progress

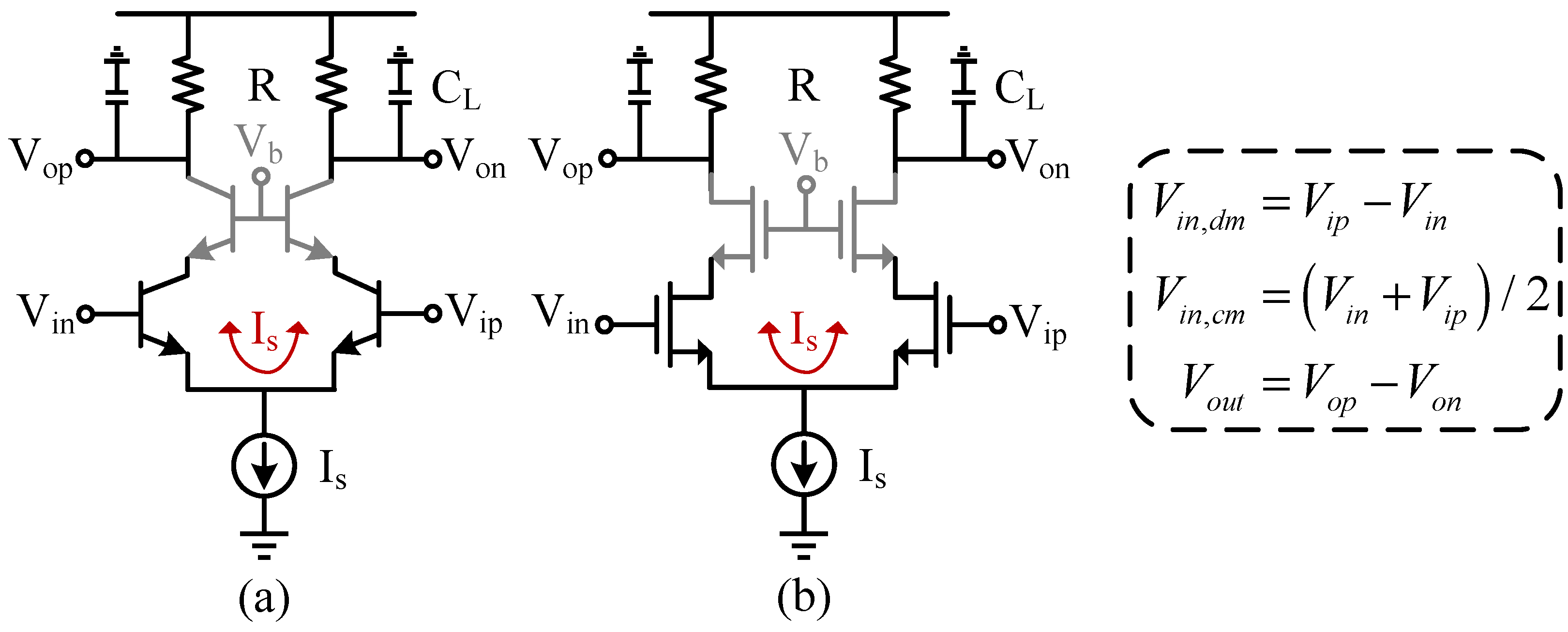

2.1. CML Circuit Principles

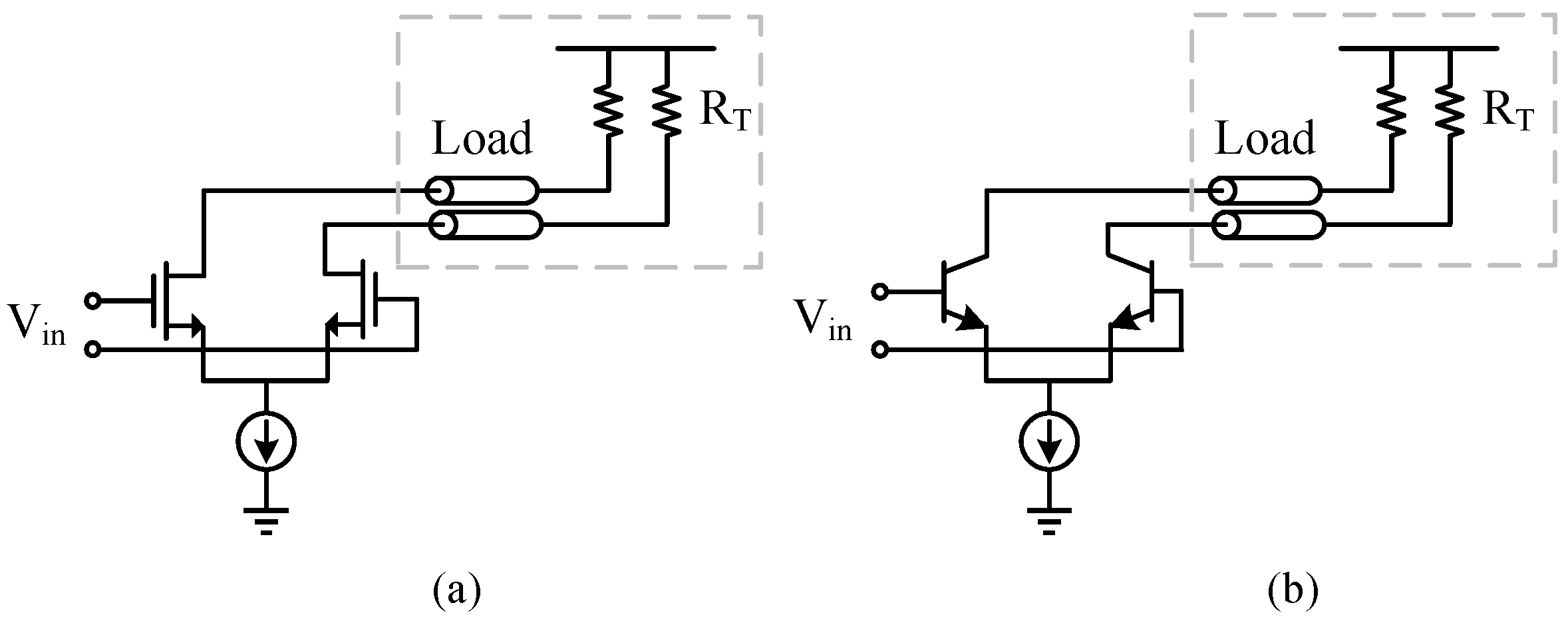

2.2. Various Load Characteristics of CML Drivers

- Coupling: DC or AC. If the driver is directly coupled to the load, it is necessary to set the output DC operating point according to the load characteristics. Open-drain (OD) or open-collector (OC) structures can be adopted to place the terminating resistors at the far-end. If not, the circuit can be self-biased at a proper level. For optical transmitter applications, emerging silicon photonics (SiPh) technologies heterogeneously integrate photonic devices and electronic devices on the same substrate. As a consequence, the driver output can be directly coupled to the optical modulator without the need for DC block and packaging wires, which increases the integration, power efficiency, and signal quality.

- Wiring: single-ended or differential. If the load is single-ended, only one terminal is connected out, which is not conducive to the balance of current signals flowing across differential branches. Integrating a dummy load to another terminal is a feasible solution. An unbalanced CML structure can also be adopted to fit the DC point and AC performance with a specific load [9,10]. For CMOS technologies scaling down to 7 nm or below, differential connection is more essential given the limited voltage headroom below 0.8 V.

- Impedance matching. Regardless of the coupling and wiring method, it is crucial to maintain the continuity of the characteristic impedance on the signal transmission link. For a standard circuit system, the terminating resistor R is fixed to 50 , and the output amplitude is determined by the tail current. But drivers used for optical modulators and other non-electrical devices have a non-standard load impedance. For load characteristic impedance higher than 50 , the terminating resistor R can be set higher to match output load and lower tail current while maintaining the same output amplitude [11]. If the characteristic impedance is very low, on the other hand, the implementation of high-swing CML drivers is very power-consuming. Optimized structures such as push–pull CML can be adopted to improve the driving strength. The driver structures suitable for different load characteristics are described in Section 5.

2.3. Research Progress

- Technology. CMOS is the most common technology, where the feature size of MOSFET plays the major role in the cut-off frequency . For SiGe HBT, GaAs pHEMT, and InP DHBT, is determined by many device properties aside from feature size. The breakdown voltage of the transistors limits the driver’s maximum swing.

- Data rate. Basically, the maximum achievable data rate is limited by the transistor’s cut-off frequency , unless numerous bandwidth extension techniques are adopted, whereas PAM4 and PAM8 signal modulation reduce bandwidth demand with minimal increases in circuit complexity, thereby improving power efficiency (FoM).

- Output swing, power supply, and FoM. Generally, the higher the required signal amplitude, the greater the power supply and power consumption, and the more difficult it is to achieve high linearity. Typically, driver ICs in CMOS technology have better FoM because of the advantageous structures and low power supply.

- Application. For serial links, high data rate and power efficiency are the top priorities, so CMOS technologies are most commonly chosen. For EOMs such as MZM and MRM, the load characteristic impedance is not the standard 50 , and high electrical amplitude is required to achieve high optical modulation amplitude (OMA), so SiGe BiCMOS, InP DHBT, and pHEMT technologies are more advantageous for their high , , and breakdown voltage. Especially, direct modulation lasers such as VCSEL and DFB are single-ended current-driven modulators, so the corresponding driver has a relatively low voltage swing and high power consumption.

- Architecture and technique. Some driver ICs only amplify the input signal, so their structures typically comprise VGA, EQ, PreAmp, and output driver. Some transmitter ICs incorporate additional functions such as multiplexing and PAM4 encoding, so their architectures include serializers. Most designs focus on innovations in equalization, bandwidth expansion, gain control, and termination strategies, resulting in improvements in equalizer tuning range, driver linearity, data rate, and power efficiency. Notably, equalizers have become essential in modern communication systems to extend the system-level channel capacity. Among the diverse equalizer architectures, CTLE and FFE are most commonly integrated in CML drivers and transmitters. Structured as a digital or analog high-pass finite impulse response (FIR) filter, FFE increases complexity, power, and area compared to CTLE, but it can be precisely tuned to counteract the loss of a known channel without amplifying noise.

| Technology | Year | Data Rate & Modulation | Swing () | Power Supply (V) | FoM (pJ/bit) | Application | Architecture & Technical Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 nm CMOS | 2020 [15] | 112 Gb/s PAM4 | 0.72 (Dif.) | 1.2 | 2.17 | Serial link | Serializer + linearity-optimized driver with fractional-spaced FFE |

| 40 nm CMOS | 2025 [16] | 96 Gb/s PAM8 | 1.6 (Dif.) | 1.2 & 2.2 | 3.64 | Serial link | Serializer + cascode driver with variable FFE |

| 28 nm CMOS | 2019 [17] | 40 Gb/s PAM4 | 0.9 (Dif.) | 0.9 | 0.5 | Serial link | Serializer + SST-CML driver with 3-tap hybrid-path FFE |

| 28 nm CMOS | 2025 [18] | 50 Gb/s PAM4 | 1.07 (Dif.) | 1 & 1.1 | 1.45 | Serial link | Serializer + two-type hybrid driver + pre-emphasis EQ |

| 65 nm CMOS | 2017 [19] | 80 Gb/s PAM4 | 2 (Dif.) | 2.5 | 2.25 | EOMs | VGA + variable EQ + OD driver |

| 150 nm 110 GHz GaAs pHEMT | 2021 [20] | 30 Gb/s PAM4 | 3 | -5.2 | 40.9 | Laser Diode | Two-slice CML driver with back-termination |

| 65 nm CMOS | 2024 [21] | 32 Gb/s NRZ | / | 12 | DFB | CTLE + buffer + Output driver with active back-termination | |

| 65 nm CMOS | 2023 [9] | 25 Gb/s NRZ | 0.4 | 2.2 | 0.83 | VCSEL | Unbalanced CML driver |

| 28 nm CMOS | 2017 [22] | 40 Gb/s NRZ | / | 1 & −1.1 | 0.5 | VCSEL | Tunable EQ + CML driver |

| 14 nm CMOS | 2017 [23] | 42 Gb/s NRZ | 0.6 | / | 1.94 | VCSEL | Unbalanced driver + edge detector with differentiator |

| 130 nm 250 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2023 [24] | 25 Gb/s NRZ | 0.32 | 1.8 & 2.5 & 3.3 | 5.49 | VCSEL | CML drivers with pre-equalization |

| 130 nm 250 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2016 [25] | 40 Gb/s NRZ | 2 (Dif.) | 2.5 | 2.25 | MRM | Cascaded drivers with current-density optimization |

| 250 nm 220 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2021 [26] | 25 Gb/s NRZ | 3 (Dif.) | 2.5 & 4.5 | 13.16 | MRM | Cascaded CML buffers |

| 250 nm 190 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2022 [27] | 37 Gb/s NRZ | 7.6 (Dif.) | 6.4 | 39 | MZM | CML OC driver with negative capacitor |

| 180 nm 290 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2024 [28] | 4 × 112 Gb/s PAM4 | 3 (Dif.) | 3.3 | 4.8 | MZM | Active feedback CTLE + VGA + OC driver |

| 55 nm 300 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2017 [29] | 168 Gb/s PAM8 | 3.8 (Dif.) | 2.5 & 3.3 & 6 | 4.88 | MZM | PreAmp + SSEFPP driver |

| 90 nm 310 GHz SiGe BiCMOS | 2024 [30] | 80 Gb/s PAM4 | 3.2 (Dif.) | 3.3 & 6.5 | 13.75 | MZM | VGA + CTLE + SEFPP driver with asymmetric T-coil peaking |

| 250 nm 400 GHz InP DHBT | 2016 [31] | 112 Gb/s PAM4 | 1.8 (Dif.) | 5 | 7.5 | MZM | VGA + distributed CML Bufs |

| 500 nm 350 GHz InP DHBT | 2025 [32] | 200 Gb/s PAM4 | 4 (Dif.) | −5.2 | 4.3 | EOMs | PreAmp + OC driver with R-C base ballast |

3. Bandwidth Expansion Techniques

3.1. Shunt Inductive and T-Coil Peaking Technique

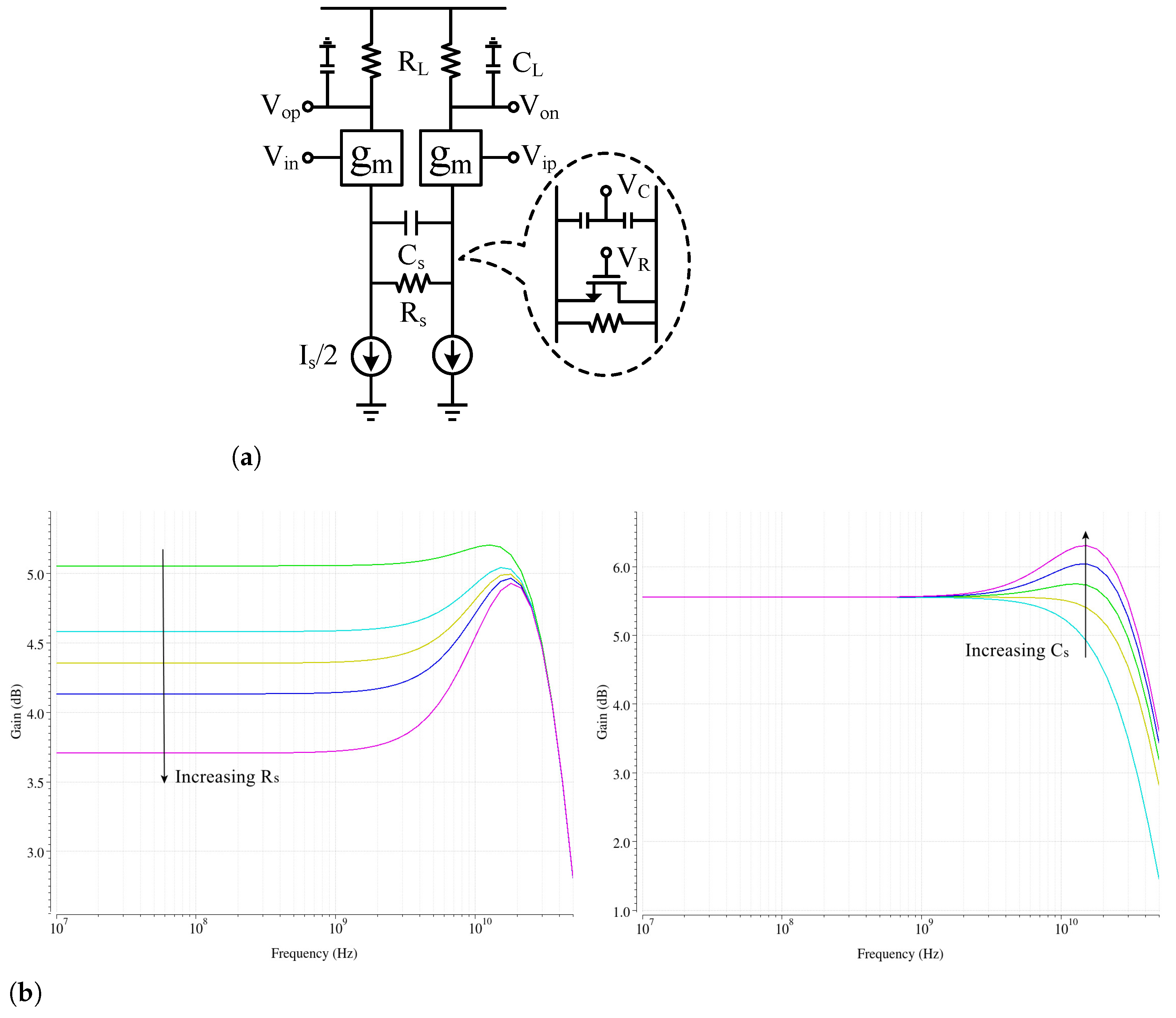

3.2. Capacitor and Resistor Degeneration Technique

3.3. Negative Capacitor Technique

3.4. Doubling Technique

4. Amplitude and DC Level Adjustment Techniques

4.1. Manual Control

4.1.1. Basic Ideas

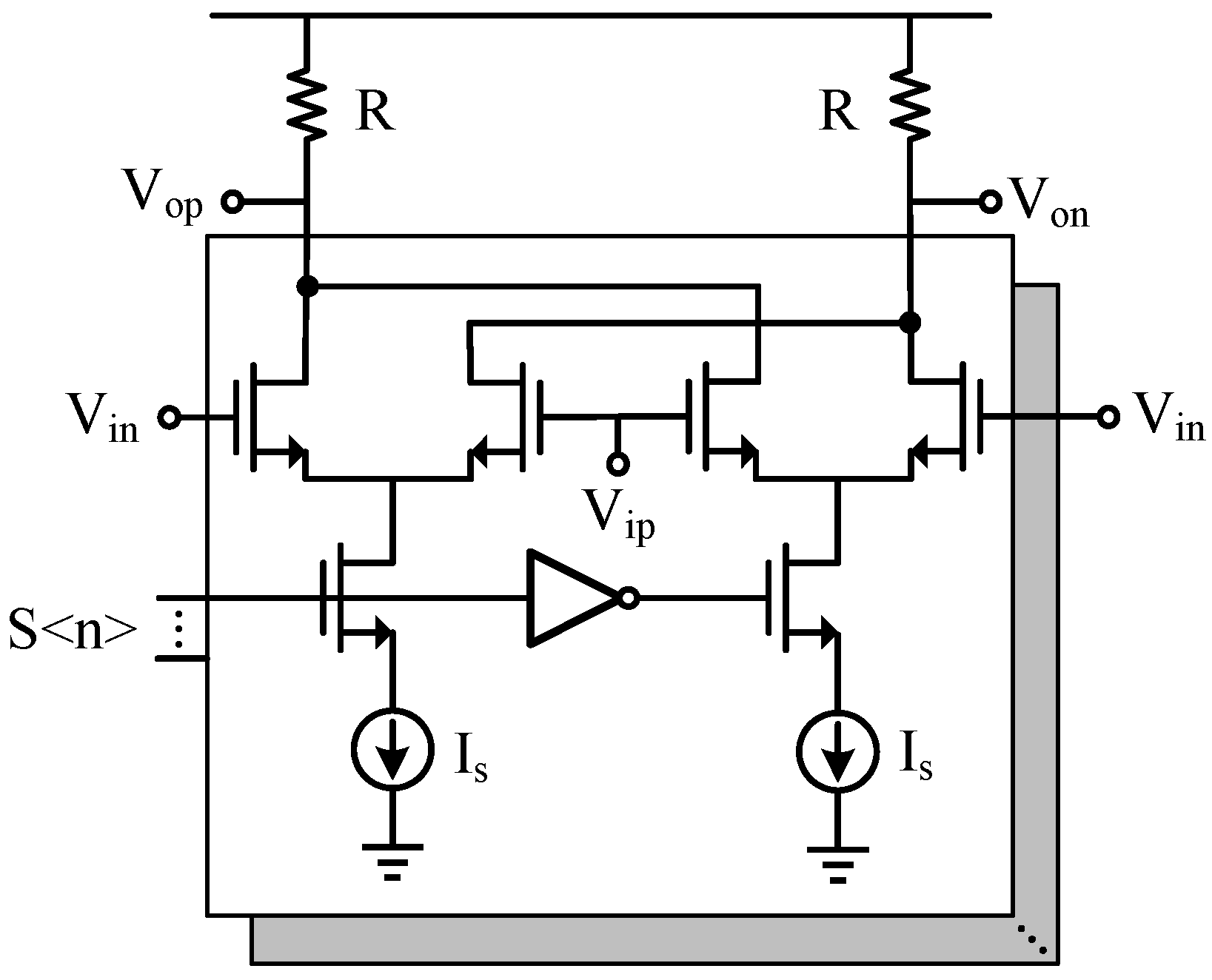

4.1.2. Cross-Coupled Pair Arrays

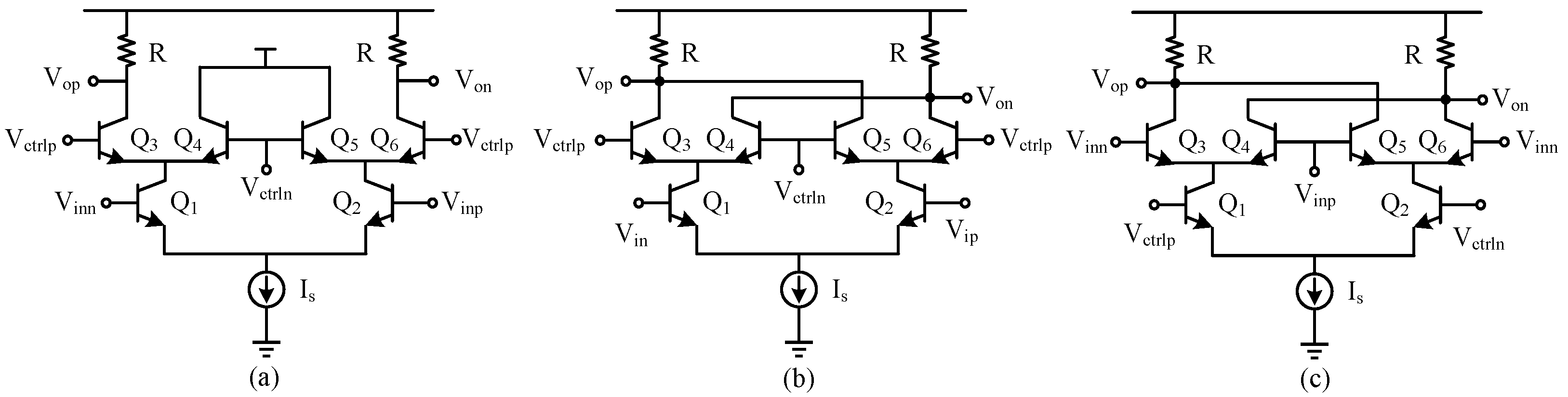

4.1.3. Gilbert Cell

4.2. Automatic Control Loop

4.2.1. Automatic Gain Control (AGC)

4.2.2. DC Offset Cancellation

5. CML Variants for Different Applications

5.1. CML Circuits for High-Order Modulation Signal Combination

5.2. Open-Drain (Open-Collector) Driver

5.3. Push–Pull CML Driver

5.4. Stacked and Unstacked Tailless CML Driver

5.5. CML-SST Hybrid Driver

6. Key Design Considerations for High-Speed High-Swing CML Circuits

6.1. General Design Rules

- The DC current and voltage of transistors in the high-speed path should be biased at peak based on device models. Technology non-ideal characteristics and reliability issues should be considered during layout and post simulation according to technology design guidelines, such as latch-up, hot carrier degradation, and MOSFET well proximity effect.

- Differential high-speed interconnects should be as short and symmetrical as possible, and isolated from other low-speed modules. During parasitics extraction, parasitic inductance should be extracted and simulated more accurately by electromagnetic tools such as ADS and EMX in addition to RC extraction tools such as xRC, qRC, and StarRC.

- The resistance of on-die power grids and package-level interconnects causes a localized reduction in the effective seen by internal circuits, which is an increasingly severe issue with the relentless scaling of CMOS processes to 7 nm and below. Advanced chip fabrication technologies such as backside power delivery network effectively improve localized power delivery [57], but they require co-design of crosstalk reduction, thermal management, and mechanical stress protection. For chip-level design, power supply and ground wires can be meshed with multiple metal layers to reduce wiring resistance and increase filtering capacitance through power-ground parasitics. Electromigration and IR-drop (EMIR) simulations should be conducted to ensure power integrity.

6.2. Cascode Structure for High-Swing Drivers

6.3. Input and Output Interface

7. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Gentili, F.; Urbani, L.; Bianchi, G.; Pelliccia, L.; Sorrentino, R. p-i-n-Diode-Based Four-Channel Switched Filter Bank with Low-Power TTL-Compatible Driver. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2014, 62, 3333–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.W.; Lin, T.H. A 0.3V, 625Mbps LVDS Driver in 0.18μm CMOS Technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Semiconductor Electronics (ICSE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28–29 July 2020; pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakkel, N.; Mortazavi, M.; Overwater, R.W.J.; Sebastiano, F.; Babaie, M. A Cryo-CMOS DAC-Based 40-Gb/s PAM4 Wireline Transmitter for Quantum Computing. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2024, 59, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Choudhary, B.; Saha, R.; Rajput, D.S. Analysis, Design and Optimization of Current Mode Logic: A State-of-the Art Review. IETE Tech. Rev. 2025, 42, 682–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioto, M.; Palumbo, G. Modeling and optimized design of current mode MUX/XOR and D flip-flop. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Analog. Digit. Signal Process. 2000, 47, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, C. Cryo-CMOS Dual-Qubit Homodyne Reflectometer Array with Degenerate Parametric Amplification. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2024, 59, 3290–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansen, W.M.C. Analog Design Essentials; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, B. Design of Analog CMOS Integrated Circuits, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, D.; Takahashi, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Inoue, T.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kishine, K. 4-ch 25-Gb/s Small and Low-power VCSEL Driver Circuit with Unbalanced CML in 65-nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2023 20th International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 25–28 October 2023; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, B.; Christoph Scheytt, J. 40 Gb/s VCSEL driver IC with a new output current and pre-emphasis adjustment method. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–22 June 2012; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, G.; Szilagyi, L.; Henker, R.; Jörges, U.; Ellinger, F. Design of a 56 Gbit/s 4-level pulse-amplitude-modulation inductor-less vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser driver integrated circuit in 130 nm BiCMOS technology. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 2015, 9, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperman, M. High speed current mode logic for LSI. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 1980, 27, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, G.; Lin, S.; Shang, H.; Lin, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, P.; Lin, C.; Yu, K.; Lee, W.; et al. 2nm Platform Technology Featuring Energy-Efficient Nanosheet Transistors and Interconnects Co-Optimized with 3DIC for AI, HPC and Mobile SoC Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–11 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Chen, K.N.; Goel, S.K.; Li, H.; Marinissen, E.J. Guest Editorial 2.5D/3D Chiplet Circuits and Systems, EDA, Advanced Packaging, and Test—Part I. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2025, 15, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ding, H.; Zhao, F.; Wu, D.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J.; Lv, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. A 50–112-Gb/s PAM-4 Transmitter with a Fractional-Spaced FFE in 65-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2020, 55, 1864–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Yang, J.; Song, E.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Han, J. A 96-Gb/s 1.6-Vppd PAM-8 Transmitter with High-Swing and Low-Loading Cascaded Driver in 40-nm CMOS Technology. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2025, 33, 2084–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Yu, W.H.; Mak, P.I.; Martins, R.P. A 40-Gb/s PAM-4 Transmitter Using a 0.16-pJ/bit SST-CML-Hybrid (SCH) Output Driver and a Hybrid-Path 3-Tap FFE Scheme in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2019, 66, 4850–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Sim, C.; Choi, J.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, C. A 50 Gb/s PAM-4 Transceiver with High-Swing Driver, Dual-Loop Analog Equalizer, and Integrator-Based Baud-Rate Linear CDR for Short-Reach Links. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Nagatani, M.; Nogawa, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Tsuzuki, K.; Nosaka, H. A 2.25-mW/Gb/s 80-Gb/s-PAM4 linear driver with a single supply using stacked current-mode architecture in 65-nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on VLSI Circuits IEEE, Kyoto, Japan, 5–8 June 2017; pp. C322–C323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, A.; Cheng, L.; Lin, F. A 15 Gbps-NRZ, 30 Gbps-PAM4, 120 mA laser diode driver implemented in 0.15-μm GaAs E-mode pHEMT technology. J. Semicond. 2021, 42, 072401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, T.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Lin, Y.; Peng, H.; et al. A 32Gb/s NRZ Low-Bias DFB Driver with Frequency Boosting for High Efficiency Data Transmission. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Singapore, 19–22 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Bakhtiar, A.; Lee, M.G.; Carusone, A.C. A 40-Gbps 0.5-pJ/bit VCSEL driver in 28nm CMOS with complex zero equalizer. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–3 May 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafaji, M.; Pliva, J.; Henker, R.; Ellinger, F. A 42-Gb/s VCSEL Driver Suitable for Burst Mode Operation in 14-nm Bulk CMOS. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2018, 30, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, W.; Zhu, E.; Xu, J. A 25Gb/s VCSEL driver with overshoot suppression in 0.13μm SiGe BiCMOS technology. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2023, 115, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Klar, H.; Gerfers, F.; Kissinger, D. A 40 Gbps Micro-Ring Modulator Driver Implemented in a SiGe BiCMOS Technology. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Compound Semiconductor Integrated Circuit Symposium (CSICS), Austin, TX, USA, 23–26 October 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, M.H.; Jo, Y.; Kim, H.K.; Lischke, S.; Mai, C.; Zimmermann, L.; Choi, W.Y. Silicon electronic–photonic integrated 25 Gb/s ring modulator transmitter with a built-in temperature controller. Photonics Res. 2021, 9, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuglea, A.; Belfiore, G.; Khafaji, M.M.; Henker, R.; Ellinger, F. A 37-Gb/s Monolithically Integrated Electro-Optical Transmitter in a Silicon Photonics 250-nm BiCMOS Process. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 2080–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Lu, D.; He, J.; Li, G.; Liu, M.; Dang, Z.; Xiao, X.; et al. A 4×112 Gb/s PAM-4 Silicon-Photonic Transmitter and Receiver Chipsets for Linear-Drive Co-Packaged Optics. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2024, 59, 3263–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, A.; Schvan, P.; Voinigescu, S.P. Linear Large-Swing Push–Pull SiGe BiCMOS Drivers for Silicon Photonics Modulators. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2017, 65, 5355–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhu, E. A 56-GBaud lumped linear push–pull driver for Mach–Zehnder modulator in 130-nm SiGe technology. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2024, 66, e34148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakita, H.; Nagatani, M.; Kurishima, K.; Ida, M.; Nosaka, H. An over-67-GHz-bandwidth 2 Vppd linear differential amplifier with gain control in 0.25-μm InP DHBT technology. In Proceedings of the IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–27 May 2016; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersent, R.; Blache, F.; Jorge, F.; Nodjiadjim, V.; Davy, N.; Mismer, C.; Riet, M.; Iotti, L.; Rylyakov, A.; Konczykowska, A.; et al. High-Efficiency >110-GHz-Bandwidth 4-Vppd InP-DHBT Linear Modulator Driver for Beyond-200-GBd Optical Transceivers. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE BiCMOS and Compound Semiconductor Integrated Circuits and Technology Symposium (BCICTS), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–15 October 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, M.S.; Wu, J.M.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, F.T.; Chiu, C.T.; Hsu, S.S. A 10-Gb/s CML I/O circuit for backplane interconnection in 0.18-μm CMOS technology. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2009, 17, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, B. The Bridged T-Coil [A Circuit for All Seasons]. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 2015, 7, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.-K.; Lee, B.-J.; Jeong, D.-K. Design Optimization of On-Chip Inductive Peaking Structures for 0.13-μm CMOS 40-Gb/s Transmitter Circuits. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2009, 56, 2544–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H. A 56-Gbps PAM-4 Wireline Receiver with 4-Tap Direct DFE Employing Dynamic CML Comparators in 65 nm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2022, 69, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, C. A 30Gbps power-efficient dual-loop adaptive equalizer in 0.13μm SiGe BiCMOS technology. Microelectron. J. 2020, 100, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Guo, D.; Chen, Q.; Fang, N.; Gan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Yi, L. A 25 Gbps VCSEL driving ASIC: An attempt for ultra-high-speed front-end readout applications. J. Instrum. 2022, 17, C01040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knochenhauer, C.; Scheytt, J.C.; Ellinger, F. A Compact, Low-Power 40-GBit/s Modulator Driver with 6-V Differential Output Swing in 0.25-μm SiGe BiCMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2011, 46, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Hella, M.M. A 30–75 dBΩ 2.5 GHz 0.13-μm CMOS Receiver Front-End with Large Input Cap. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2016, 63, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Huang, S.; Li, Z.; Yin, P.; Zang, J.; Fu, D.; Tang, F.; Bermak, A. A 5-13.5 Gb/s multistandard receiver with high jitter tolerance digital CDR in 40-nm CMOS process. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2020, 67, 3378–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, C.; Zhu, E. 4-channel, 224Gb/s PAM-4 optical transmitter with group delay compensation in 130-nm BiCMOS technology. IEICE Electron. Express 2023, 20, 20230386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammei, E.; Loi, F.; Radice, F.; Dati, A.; Bruccoleri, M.; Bassi, M.; Mazzanti, A. Analysis and Design of a Power-Scalable Continuous-Time FIR Equalizer for 10 Gb/s to 25 Gb/s Multi-Mode Fiber EDC in 28 nm LP CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2014, 49, 3130–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awny, A.; Nagulapalli, R.; Kroh, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Runge, P.; Micusik, D.; Fischer, G.; Ulusoy, A.C.; Ko, M.; Kissinger, D. A Linear Differential Transimpedance Amplifier for 100-Gb/s Integrated Coherent Optical Fiber Receivers. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2018, 66, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangerow, C.V.; Goettel, B.; Awny, A.; Kissinger, D.; Zwick, T. Broadband variable gain amplifier with low group delay variation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 18th Topical Meeting on Silicon Monolithic Integrated Circuits in RF Systems (SiRF), Anaheim, CA, USA, 14–17 January 2018; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, F.; Gao, Y.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y. A 1GHz CMOS variable gain amplifier with 70dB linear-in-magnitude controlled gain range for UWB systems. In Proceedings of the 2009 15th Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications, Shanghai, China, 8–10 October 2009; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Xuan, Z.; Li, H.; Kim, T.; Kumar, R.; Sakib, M.N.; Hsu, C.M.; Ma, C.; Rong, H.; Balamurugan, G.; et al. Silicon Photonic Microring-Based 4 × 112 Gb/s WDM Transmitter with Photocurrent-Based Thermal Control in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2022, 57, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chiang, P.C.; Peng, P.J.; Chen, L.Y.; Weng, C.C. Design of 56 Gb/s NRZ and PAM4 SerDes Transceivers in CMOS Technologies. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2015, 50, 206–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, H.S.; Do, H.; Jeong, G.S.; Koh, D.; Park, S.H.; Jeong, D.K. 4-Channel Push-Pull VCSEL Drivers for HDMI Active Optical Cable in 0.18-μm CMOS. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design, Seattle, WA, USA, 23–25 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Jeong, G.S.; Bae, W.; Park, J.E.; Yoon, C.S.; Yoon, J.M.; Joo, J.; Kim, G.; Jeong, D.K. A 32 Gb/s, 201 mW, MZM/EAM Cascode Push–Pull CML Driver in 65 nm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2018, 65, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak-Deniz, Z.; Dickson, T.O.; Cochet, M.; Proesel, J.; Bulzacchelli, J.F.; Ainspan, H.; Brändli, M.; Morf, T.; Beakes, M.; Meghelli, M. A 0.88pJ/bit 112Gb/s PAM4 Transmitter with 1Vppd Output Swing and 5-Tap Analog FFE in 7nm FinFET CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–20 June 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.U.; Chae, J.H. A Single-Ended PAM-4 Transmitter Using Unstacked Tailless CML Driver and Coefficient-Corrected FFE for Memory Interfaces. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 6306–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Im, H.; Yang, J.; Song, E.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Shin, T.; Han, J. A 100-Gb/s PAM-8 Transmitter with 3-Tap FFE and High-Swing Hybrid Driver in 40-nm CMOS Technology. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 2936–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, R.; Lv, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Yuan, L.; Xin, K.; Huang, H.; Ding, H.; Lai, M. A 0.9 pJ/Bit 56Gb/s High-Swing Tri-Mode Wireline Transmitter with 6-Bit DAC Controlled Tailless-CML Driver and Impedance Calibration Loop. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium—IMS 2025, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2025; pp. 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, M.; Radice, F.; Bruccoleri, M.; Erba, S.; Mazzanti, A. A High-Swing 45 Gb/s Hybrid Voltage and Current-Mode PAM-4 Transmitter in 28 nm CMOS FDSOI. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2016, 51, 2702–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L. A 56-Gb/s 0.11-pJ/bit/dB energy-efficient PAM-4 transmitter using push-pull current-mode driver and DDJ-suppressed multiplexer. IEICE Electron. Express 2025, 22, 20250110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.G.; Lim, S.K. BS-PDN-Last: Towards Optimal Power Delivery Network Design With Multifunctional Backside Metal Layers. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rito, P.; López, I.G.; Awny, A.; Ulusoy, A.C.; Kissinger, D. A DC-90 GHz 4-Vpp differential linear driver in a 0.13 μm SiGe:C BiCMOS technology for optical modulators. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), Honololu, HI, USA, 4–9 June 2017; pp. 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, B.; Niknejad, A.M. X/Ku Band CMOS LNA Design Techniques. In Proceedings of the IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference 2006, San Jose, CA, USA, 10–13 September 2006; pp. 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.L.; Coen, C.T.; Shankar, S.; Cressler, J.D. Best practices to ensure the stability of SiGe HBT cascode low noise amplifiers. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Bipolar/BiCMOS Circuits and Technology Meeting (BCTM), Portland, OR, USA, 30 September–3 October 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.; Meister, T.; Rest, M.; Rein, H.M. SiGe driver circuit with high output amplitude operating up to 23 Gb/s. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 1999, 34, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, M.S.; Chen, F.T.; Hsu, Y.H.; Wu, J.M. 20-Gb/s CMOS EA/MZ Modulator Driver with Intrinsic Parasitic Feedback Network. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2014, 22, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettrich, H.; Moller, M. Linear low-power 13GHz SiGe-Bipolar modulator driver with 7 Vpp differential output voltage swing and on-chip bias tee. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Bipolar/BiCMOS Circuits and Technology Meeting (BCTM), Coronado, CA, USA, 28 September–1 October 2014; pp. 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, R.; Dong, Z.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Cops, W.F.; Chen, T.; Liu, L.; Qi, N. A 224-Gb/s PAM-4 Linear Distributed Driver for Silicon-Photonic Modulators in SiGe BiCMOS. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium (RFIC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–17 June 2025; pp. 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, S.; Razavi, B. Broadband esd protection circuits in CMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2003, 38, 2334–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TTL | CMOS | LVDS | ECL PECL LVPECL | CML | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level range (V) | 0∼5 | 0∼VCC | 0.85∼1.55 | −1.72∼−0.88 3.28∼4.12 1.58∼2.42 | VCC-0.4 ∼VCC |

| Max. rate level (Hz) | 100 M | 100 M | 1 G | 10 G | 10 G |

| Power level | High | Low | Low | High | Medium |

| Single/differential | Single | Single | Dif. | Dif. | Dif. |

| Coupling | AC | DC | DC | DC/AC | DC/AC |

| Techniques | Simplicity | Bandwidth Improvement | Additional Power | Area Cost | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shunt inductive & T-coil peaking | +++ | ∼1.8×, 2.8× | - | +++ | Inductor SRF; Consistency between simulation and measurement |

| Capacitor and resistor degeneration | +++ | vary by R, C | - | + | Lowered gain |

| Cross-coupled negative capacitor | + | ∼1.3× | ✓ | ++ | Capacitor value selection; layout symmetry |

| Negative Miller capacitor | ++ | ∼1.3× | - | + | Capacitor value selection; layout symmetry |

| doubling | + | ∼2× | ✓ | ++ | Higher output capacitance; layout symmetry |

| Structure | Simplicity | Power Efficiency | Output Swing | Matching Methods | Preferred Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cascode) differential pair | +++ | + | +++ | Internal resistors | Widely applicable |

| OC/OD | +++ | ++ | +++ | External resistors | Need external termination |

| Push–pull | ++ | ++ | ++ | Parallel transistors | Low load resistance |

| Tailless | ++ | +++ | + | Internal resistors | In CMOS technology, low power supply |

| CML-SST hybrid | + | +++ | + | Internal series resistors + parallel transistors | In CMOS technology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, J. Research Progress and Design Considerations of High-Speed Current-Mode Driver ICs. Electronics 2026, 15, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020405

Chen Y, Chen Y, Wu C, Chen J. Research Progress and Design Considerations of High-Speed Current-Mode Driver ICs. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020405

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yinghao, Yingmei Chen, Chenghao Wu, and Jian Chen. 2026. "Research Progress and Design Considerations of High-Speed Current-Mode Driver ICs" Electronics 15, no. 2: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020405

APA StyleChen, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, C., & Chen, J. (2026). Research Progress and Design Considerations of High-Speed Current-Mode Driver ICs. Electronics, 15(2), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020405