1. Introduction

The automatic navigation system has become a core technology for the intelligentization of agricultural equipment and for achieving large-scale yield improvement in China’s grain and oil crops. Path-tracking control stability is a key performance indicator for unmanned agricultural operations, which rely on navigation perception and decision-making to guide machinery along predetermined trajectories with high precision, thereby reducing labor intensity and improving operational consistency [

1]. The farmland environment is characterized by surface undulations and low soil adhesion coefficients, where tire slip and vehicle sideslip make path-tracking control more complex than autonomous driving of vehicles on paved roads. The centroid sideslip angle reflects the degree of deviation caused by steering or lateral forces during vehicle motion and is an important state variable indicating lateral stability and wheel–ground interaction [

2,

3]. With the increasing adoption of unmanned agricultural machinery, improving the scenario adaptability of navigation control systems has garnered significant attention.

While classical path-tracking methods like PID, pure pursuit, and Stanley perform adequately on flat terrain or at low speeds [

4,

5], their performance degrades under more demanding conditions. This is largely because their fundamental assumption of negligible sideslip fails in complex field environments, often resulting in substantial lateral tracking errors or even instability, particularly on paths with high curvature. Existing approaches to enhance the adaptability of path-tracking control primarily include robust controller design and sideslip identification. Sliding mode control (SMC) offers advantages such as fast response and strong disturbance rejection. To address the chattering issue of SMC, Huang et al. proposed an SMC improved with fuzzy rules based on the kinematic model of agricultural machinery [

6]. Zhang et al. integrated feedforward PID with a preview Ackermann algorithm, proposing a three-point turn method, and validated its robustness in scenarios involving large-width combine harvesters [

7]. To tackle yaw and lateral offset for tracked sprayer robots in soft clay and inter-row space, Li et al. established a multi-body dynamics model for track–soil interaction and designed the path-following control based on variable structure sliding mode [

8]. Zhang et al. employed model linearization and robust adaptive SMC, designing a disturbance observer to compensate for external disturbances and model uncertainties [

9]. Experimental results demonstrated that the proposed methods maintain small tracking errors and good stability in the presence of significant disturbances and terrain variations. Lenain et al. established an extended kinematic model after estimating the slip angles based on the duality principle between observation and control, achieving a path-tracking error of less than 20 cm for agricultural vehicles under slip conditions [

10]. Jing et al. proposed a robust control method with slip compensation to solve the stable tracking-control problem for tractor-scrapers [

11]. Their method incorporates estimated sideslip values into the steering angle calculation for motion control, with field tests validating the effectiveness of the approach. Although the methods discussed enhance robustness in the presence of disturbances, their achievable precision is compromised by inaccuracies in the dynamic model and latency in estimating sideslip angles from sensor data. In order to address the model prediction error in tracked robots, Zhao et al. established a kinematic model incorporating slip and utilized both an extended Kalman filter (EKF) and an improved sliding mode observer for online estimation of slip parameters, providing more accurate slip estimation and future trajectory prediction with significantly reduced prediction errors compared to EKF [

12].

Model predictive control (MPC) has gradually become a mainstream solution for high-precision path-tracking control in constrained scenarios, owing to its capabilities in temporal prediction and explicit handling of state constraints. To address posture interference in paddy field transplanters, He et al. designed a position correction algorithm to improve model state accuracy and developed an MPC controller based on a kinematic model, achieving a maximum straight-line path-tracking error of less than 15 cm [

13]. For articulated steering tractors with high-precision requirements, Zhou et al. employed a genetic algorithm to optimize the prediction horizon and control horizon parameters of the MPC. The effectiveness of the algorithm was verified both through simulations and field tests [

14]. In the context of continuously varying speeds for articulated dump trucks, Shahirpour et al. incorporated cylinder dynamics and sideslip angle effects into the MPC prediction model, enabling efficient control decisions for both speed and steering angle [

15]. To further enhance path-tracking accuracy and reliability, the integration of MPC with other intelligent algorithms has gained significant attention, leveraging MPC’s constraint-handling capability and receding horizon characteristics. For instance, Kim et al. treated the look-ahead distance of the pure pursuit method as an online optimization variable in MPC, combining the simplicity of geometric tracking with MPC’s constraint management [

16]. For tractor-trailer systems subject to constraints and disturbances, Yue et al. applied MPC and adaptive fuzzy control for steering angle and speed decisions, respectively, improving control stability and robustness [

17]. Lu et al. proposed a dual-loop control framework where steering control uses MPC and dynamic control employs SMC, supplemented by a nonlinear disturbance observer for total disturbance compensation [

18]. Falcone et al. compared nonlinear MPC (NMPC) and linear time-varying MPC (LTV-MPC) in terms of computational load and application performance. They pointed out that the model-solving architecture of NMPC is difficult to deploy in high-speed vehicle control scenarios [

19]. To further reduce the computational burden of MPC, Zhou et al. analyzed the event-triggered MPC versus time-triggered MPC in both straight-line and lane-change scenarios. They highlighted that by setting appropriate event-triggered thresholds, the computational load of MPC can be effectively reduced while maintaining acceptable accuracy [

20].

Unmanned agricultural machinery is characterized by low operating speeds and high stability requirements. Moreover, different operational trajectories and speeds demand tailored optimization of path-tracking control methods. Mondal et al. compared the performance boundaries of MPC controllers based on vehicle kinematic and dynamic models in path tracking. Their study showed that kinematic models are sufficient and easier to implement at low speeds with small sideslip angles, whereas dynamic models perform better at high speeds, under large curvatures, or in the presence of significant tire nonlinearities [

21]. Wang et al. compared vehicle kinematic and dynamic models, noting that kinematic models typically ignore the interaction forces between tires and the ground, making them inadequate for handling sideslip angle disturbances at higher speeds. They employed a particle swarm optimization algorithm to tune the prediction and control horizons of the MPC [

22]. MPC based on vehicle dynamics requires the real-time identification of numerous parameters, posing significant challenges for implementation in complex field environment. As a result, simplified models are often adopted for practical MPC deployment, which, however, often struggles to maintain stable lateral control accuracy under complex road conditions such as low adhesion and large curvature. A key gap in the existing literature is the lack of analysis regarding sideslip angle effects under the characteristic speeds and path conditions of agricultural field operations. Addressing this gap forms the primary motivation for our work.

This paper proposes a kinematic MPC path-tracking model that incorporates the sideslip angle. By explicitly modeling the sideslip within the kinematic framework, the approach more accurately captures vehicle motion under low-adhesion and high-curvature field conditions. We validated the algorithm on representative agricultural paths via a Carsim–Simulink co-simulation. The testing was conducted on both the U-shaped paths (common in spraying operations) and the rectangular paths with sequential same direction turns (typical in harvesting) at different speeds to evaluate performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vehicle Kinematic Model

An extended kinematic model that considers the sideslip angle at the vehicle’s center of gravity (CG) is used for path-tracking control, where the following modeling assumptions are made:

- (1)

The left and right wheels on each axle are assumed to have identical steering angles and rotational speeds at any time, so that the two wheels on each axle can be lumped into a single equivalent wheel.

- (2)

The vehicle is assumed to operate at low to moderate speeds, and the longitudinal load transfer between the front and rear axles is neglected.

- (3)

Both the vehicle body and the suspension system are treated as rigid.

The model is presented in

Figure 1, where the shaded area represents the front and rear tires of the vehicle bicycle model. Based on geometric relationships, the kinematic equations of the vehicle in the CG coordinate system can be derived as follows:

where

denote the position of the vehicle’s center of gravity in the global coordinate frame,

is the heading angle,

is the velocity at the center of gravity,

is the sideslip angle at the CG, and

represents the distance from the CG to the rear axle.

The relationship between the CG sideslip angle

and the front-wheel steering angle

is given by:

where

is the wheelbase and

is the distance from the rear axle to the CG.

Accordingly, the system state variables can be selected as

, and the control variables as

. By performing a Taylor series expansion at the reference point, neglecting higher-order terms, and calculating the Jacobian matrix, the linearized error-state equations can be written as

where

By explicitly including the sideslip angle at the vehicle’s CG, the proposed model achieves greater accuracy than conventional kinematic models in capturing behavior during steering and lateral sliding. This enhancement lays a solid foundation for the subsequent design of an MPC-based path-tracking controller.

After establishing the kinematic model that incorporates the CG sideslip angle, the system is transformed into a discrete-time form suitable for MPC-based optimization control. The forward Euler method is employed to discretize the error-state equations. The discrete error-state model of the system is as follows:

where

denotes the sampling time and

Through this modeling approach, the original nonlinear kinematic model is converted into a linear discrete-time state-space form that is well-suited for prediction and optimization. By incorporating historical control inputs, this formulation allows constraints on input increments, forming the basis for the MPC path-tracking control law derived later.

2.2. Design of MPC Controller

An augmented state vector is introduced by incorporating historical control variables information into the original state variables. This augmentation enables the input increment to be explicitly treated as a new optimization variable, thereby allowing the controller to simultaneously consider both the system state and the previous control action:

where

represents the original state variables of the vehicle, and

denotes the control variables at the previous time step.

Substituting this definition into the state-space equation yields the augmented state-space and output equations as follows:

where

. The corresponding new output equation is:

where

,

, and

represent the dimensions of the state and control vectors, respectively;

is the identity matrix,

is the zero matrix, and

denotes the new output vector.

By expanding the augmented state-space equation over the prediction horizon, an explicit relationship between the future outputs, the current state, and the future control input sequence can be derived. Let the prediction horizon be

and the control horizon be

(

). After mathematical derivation, the predicted system output can be expressed as:

where

,

,

The above matrix formulation not only clearly characterizes the system’s dynamic response but also transforms the predicted output into a linear function of the control input increments. Consequently, the path-tracking problem can be reformulated as a standard quadratic programming (QP) optimization problem, enabling the controller to achieve optimal tracking performance while satisfying system constraints. In order to balance the tracking error and the control variables variations, and to ensure that the autonomous vehicle follows the reference path both rapidly and smoothly, it is necessary to incorporate optimization terms for both the state deviation and the control effort. The objective function is defined as:

where

,

, and

are the weight matrices,

is the weight coefficient,

is the relaxation factor, and

is the reference output at time

. The objective function can be expressed in matrix form as:

where

and

are the augmented state-weight and control-weight matrices, which can be written as

For computational convenience, the objective function can be further transformed into the standard quadratic form:

where

,

.

,

,

, and

denote the state- and control-weighting matrices, respectively.

2.3. Design of MPC Constraint Conditions

In solving the QP problem, it is necessary to consider both the control variables constraints and the control increment constraints. The control variables constraint can be expressed as:

And the control increment constraint as:

By recursively expanding Equations (11) and (12) over the control horizon, the following matrix form can be derived:

Combining Equations (11) and (12) yields:

where

and

denote the sequences of minimum and maximum control variables within the control horizon, respectively.

The above expression can be rewritten in the standard inequality constraint form:

At each control cycle, the standard quadratic programming problem is solved to obtain an optimal sequence of control input increments within the control horizon:

The first element of this optimal sequence is then applied to the system as the actual control increment:

In the next control cycle, the prediction and optimization processes are repeated, thereby forming a receding-horizon control loop that continuously adjusts the control inputs to achieve accurate and stable vehicle path tracking.

2.4. Simulation Platform and Verification Scheme

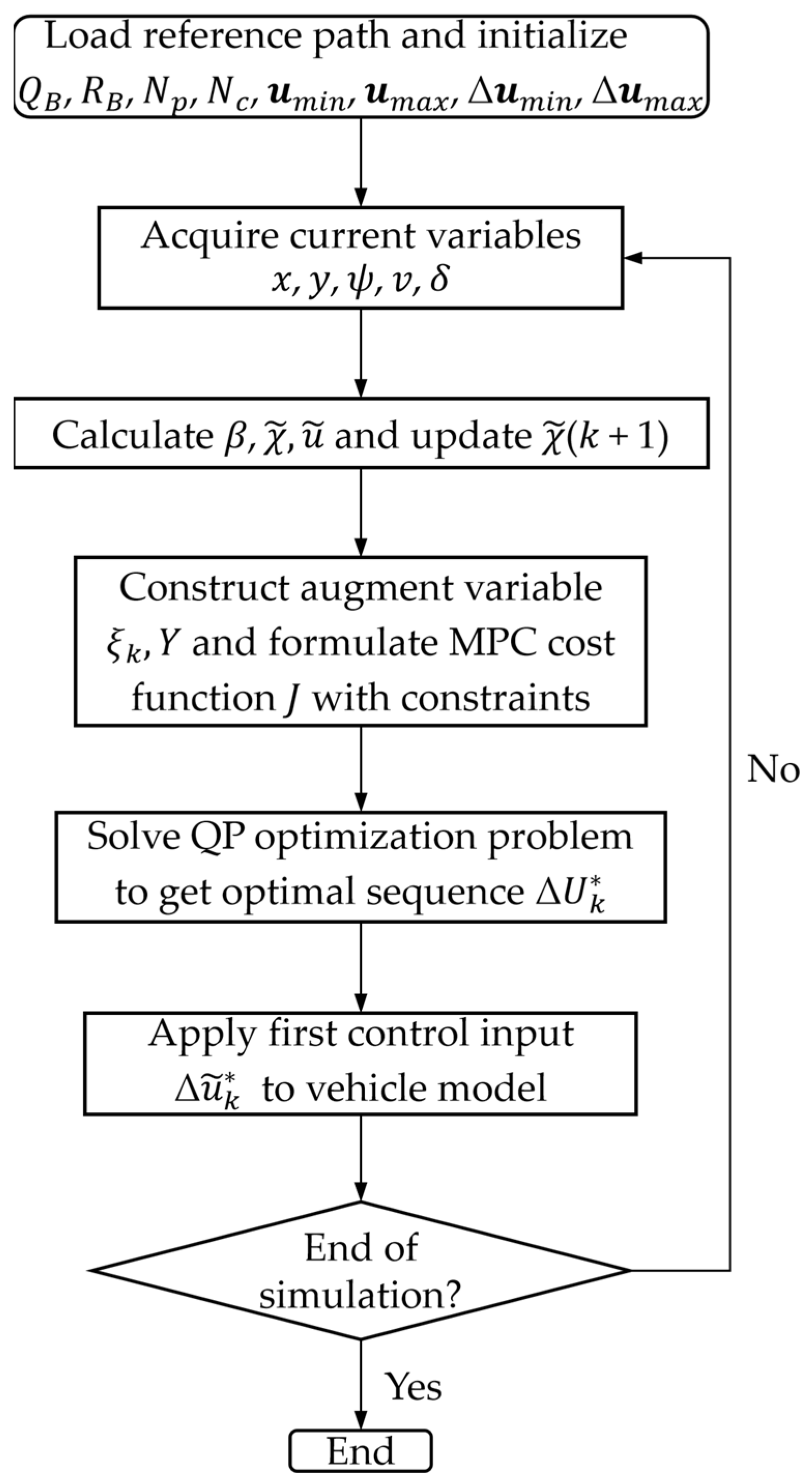

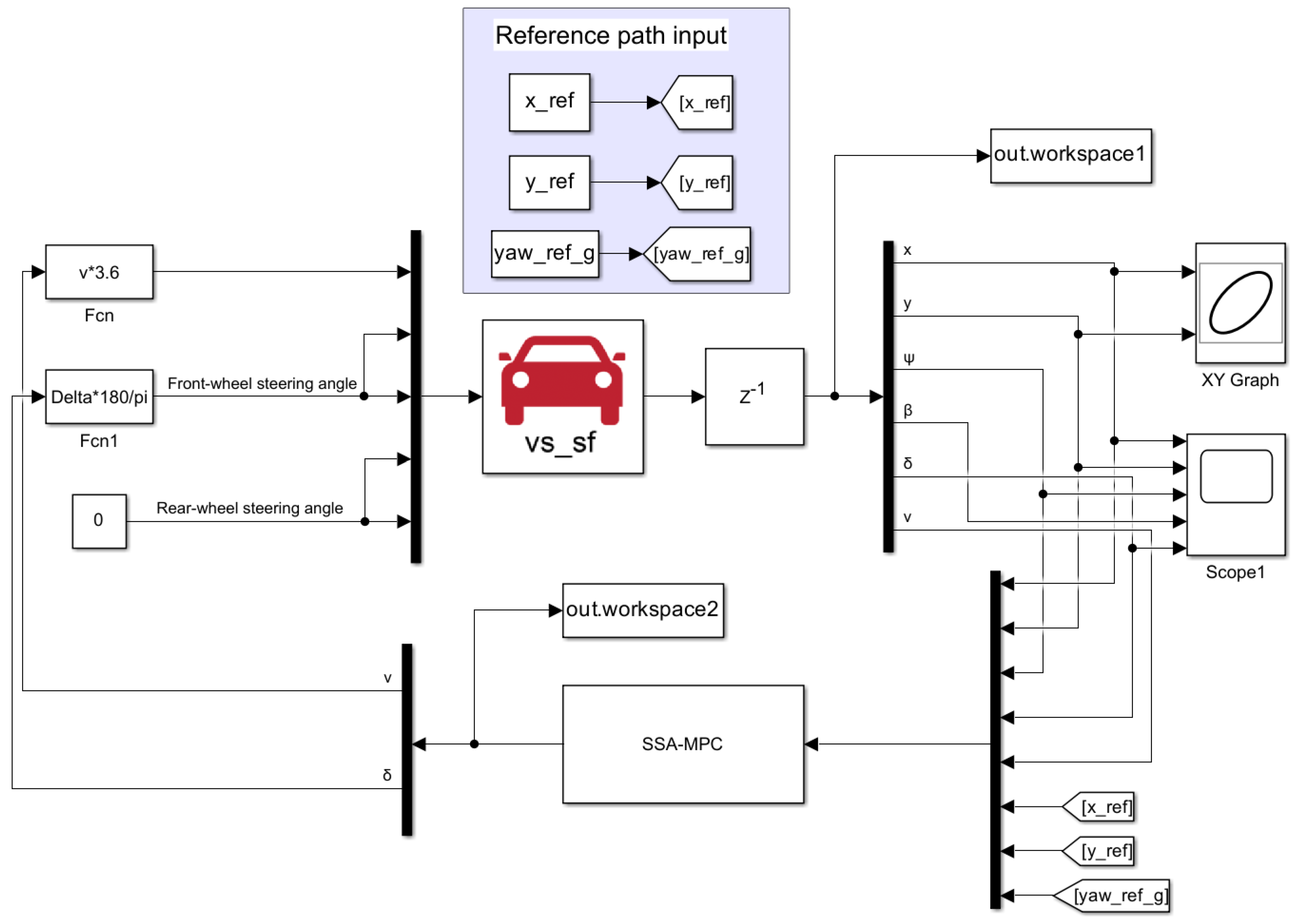

In this study, the tractor model is established in CarSim (with Version 2020.0), as CarSim is capable of accurately analyzing vehicle dynamic performance and supports data interaction with various external software platforms. The overall algorithmic flow of the proposed path-tracking controller is summarized in

Figure 2, and the CarSim–Simulink (with Version 10.6) co-simulation environment of the path-tracking system is illustrated in

Figure 3. At each period, the MPC controller receives the previous-step state variables

from the CarSim module, solves the optimization problem to obtain the optimal control variables

for the next step, and sends this input back to CarSim. CarSim then updates the vehicle motion accordingly, and this closed-loop interaction is repeated to accomplish path-tracking control.

In typical agricultural operations, the traveling speed of agricultural machinery is generally below 3 m/s. Therefore, in the simulation experiments, the vehicle speed is set to 3 m/s for straight-line operation. To analyze the tracking performance under different speeds along curved paths, different speed settings are applied to the curved trajectories. The road adhesion coefficient of dry soil road is usually 0.68. The road surface type is selected as “off-road”. The

matrix regulates the convergence rate of the tracking process, while the

matrix adjusts the stability of the control inputs. The first two diagonal elements of the

matrix reflect the sensitivity of the control system to the lateral tracking error, while the third diagonal element reflects its sensitivity to the heading error. The first diagonal element of the

matrix represents the sensitivity of the control input to changes in the longitudinal velocity, and the second diagonal element represents the sensitivity of the control input to changes in the front-wheel steering angle. By trial and error for the required performance, these matrices are chosen as follows:

After extensive simulation trials and comparative evaluations, the final set of MPC parameters (excluding parameters that are adaptively adjusted) is selected as listed in

Table 1. In order to verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, a Dongfanghong 1104 tractor (provided by YTO Group Corporation, Luoyang, China) was selected as the controlled vehicle whose parameters are listed in

Table 2. Based on these parameters, a CarSim-/Simulink-based simulation environment for agricultural machinery path tracking is constructed. This environment is used to analyze the factors influencing tracking performance as well as the adaptability of the MPC controller under various operating paths.

3. Results

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed kinematic MPC path-tracking control method that incorporates the sideslip angle at the vehicle’s CG, this section conducts a systematic performance comparison and analysis using the CarSim–Simulink co-simulation platform. Under the mild sideslip condition, the CG sideslip angle can be expressed as [

23,

24]:

where

represents the lateral component of the vehicle velocity and

represents the longitudinal component. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate how the path curvature and vehicle speed influence the CG sideslip angle and the resulting path-tracking performance. In the simulations, the vehicle kinematic model serves as the control plant, and two controllers are constructed for comparison as follows: an MPC controller without considering the CG sideslip angle, and an improved MPC controller that explicitly incorporates the CG sideslip angle constraint. The real-time vehicle sideslip angle output by the CarSim is also computed based on this formulation.

Spraying and harvesting are two of the most common operations in agricultural production. The U-shaped path is widely used for spraying operations, whereas the rectangular path is commonly adopted for harvesting. Accordingly, these two paths are selected as reference trajectories to evaluate the performance of the proposed control method in typical field environments. Both controllers are operated under identical path and speed conditions to compare their path-tracking performance across different operating scenarios. For ease of analysis, the MPC controller that incorporates the sideslip angle is simplified and denoted as SSA-MPC, while the conventional MPC is denoted as MPC. In the following simulations, the same parameters are employed for the MPC and SSA-MPC to make a fair comparison.

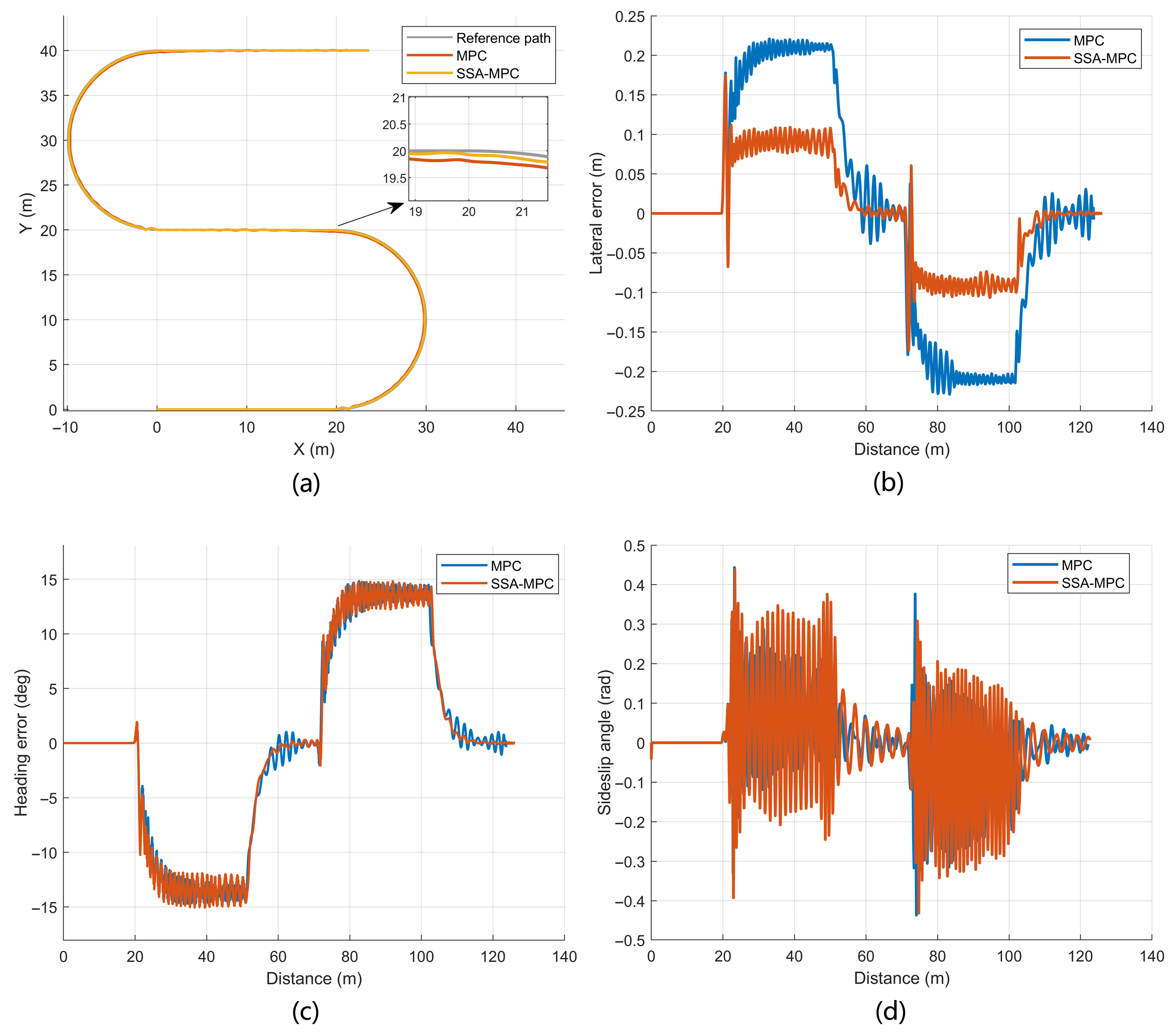

3.1. Path Tracking Under U-Shaped Path

The reciprocating U-shaped path is selected as the reference path. This path consists of multiple straight segments and two 10 mradius turns, making it suitable for evaluating the controller’s stability and response characteristics during repeated steering and re-alignment maneuvers. The initial vehicle speed is set to 3 m/s, and the speed in the curved sections is limited to 1 m/s. The total simulation duration is 120 s, and the sampling time of the controller is 0.05 s. The path-tracking results are shown in

Figure 4, and the specific error details are listed in

Table 3.

Figure 4a shows that both controllers are able to complete the U-shaped path and keep the actual trajectory close to the reference path. When the vehicle enters the two curved sections, the lateral and heading errors increase and oscillate within a certain range, and then rapidly decay on the subsequent straight segment, as seen in

Figure 4b,c. Over the whole path, the absolute lateral error of SSA-MPC does not exceed 0.174 m, whereas that of MPC reaches 0.234 m, according to

Table 3. The absolute heading error remains within 14.766° for SSA-MPC and 14.936° for MPC. The sideslip angle shown in

Figure 4d stays close to zero on most straight sections and exhibits noticeable peaks mainly at the transitions between straight and curved segments.

The quantitative comparison in

Table 3 highlights the improvement brought by SSA-MPC. For the lateral error, the absolute mean value, standard deviation, and absolute maximum value of SSA-MPC are 0.0611 m, 0.074 m, and 0.174 m, respectively, compared with 0.148 m, 0.169 m, and 0.234 m for MPC, corresponding to reductions of 58.7%, 56.2%, and 25.6%. For the heading error, the absolute mean value, standard deviation, and absolute maximum value are reduced from 9.391°, 10.892°, and 14.936° under MPC to 8.579°, 10.458°, and 14.766° under SSA-MPC, i.e., by 8.6%, 4.0%, and 1.1%, respectively. Overall, under the U-shaped path, SSA-MPC achieves higher path-tracking accuracy and tighter control of the vehicle’s yaw motion than the conventional MPC.

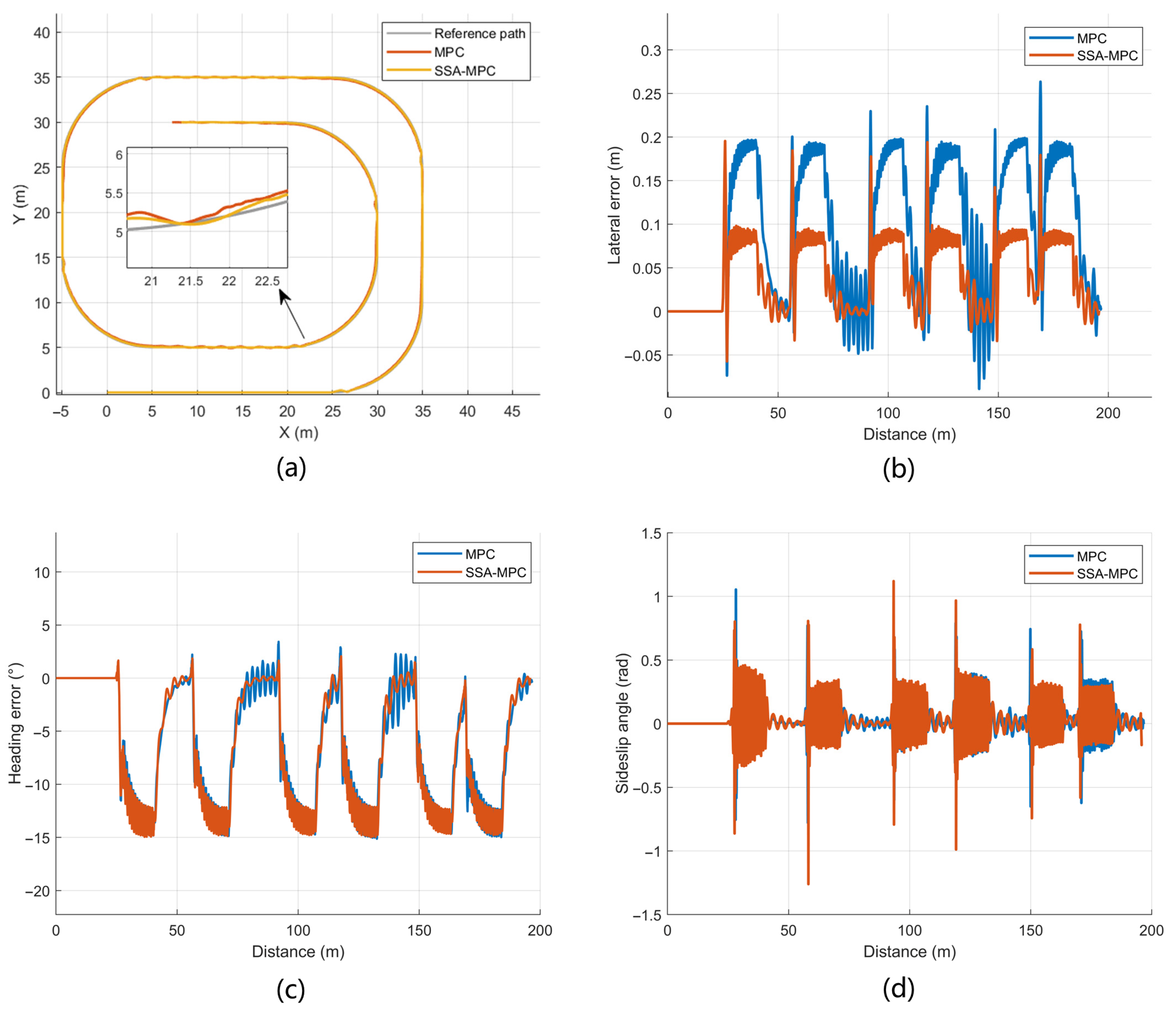

3.2. Path Tracking Under Rectangular-Shaped Path

To evaluate the controller performance under scenarios involving continuous same-direction turns, a rectangular-shaped path is selected as the reference trajectory. The path consists of several 8 m radius cornering sections connected by straight segments. The initial vehicle speed is set to 3 m/s; the curved-path speed is reduced to 1 m/s. The control sampling period is 0.05 s, and the total simulation duration is 160 s. The path-tracking results are shown in

Figure 5, and the specific error details are listed in

Table 4.

The lateral error curves in

Figure 5b exhibit a periodic pattern, with one prominent peak produced at each cornering segment. Over the entire 200 m path, the lateral error of SSA-MPC remains within 0.194 m, whereas the maximum lateral error of MPC reaches 0.263 m. The corresponding heading error responses in

Figure 5c also show periodic variations that are synchronized with the cornering sections, and the absolute maximum heading errors are 15.062° for SSA-MPC and 15.069° for MPC. The sideslip angle in

Figure 5d presents repeated peaks around the corners and small oscillations on the straight segments; in each loop, the peak sideslip amplitude and the oscillation level of SSA-MPC are smaller than those of MPC.

The quantitative indices in

Table 4 further compare the two algorithms. For the lateral error, the mean value, standard deviation, and maximum value of SSA-MPC are 0.063 m, 0.036 m, and 0.194 m, respectively, whereas those of MPC are 0.138 m, 0.077 m, and 0.248 m, corresponding to reductions of 54.3%, 53.2%, and 21.8%. For the heading error, the mean values of SSA-MPC and MPC are 8.635° and 8.885°, while the standard deviation and maximum value decrease from 5.165° and 15.084° under MPC to 5.038° and 15.062° under SSA-MPC, i.e., by 2.5% and 0.2%, respectively. Overall, under the rectangular-shaped path, SSA-MPC achieves smaller lateral error and better convergence of heading error than MPC, while maintaining a comparable level of sideslip angle. These results indicated that the proposed SSA-MPC enhances lateral stability and sideslip suppression in rectangular-shaped, harvesting-like operations, while maintaining smoother control inputs and higher path-tracking precision.

3.3. Path Tracking at Different Turning Speed

Since turning speeds during headland maneuvers are generally lower than straight-line travel speeds in field operations, it is therefore pertinent to assess path-tracking performance across a relevant speed range. A medium speed of 3 m/s and a low speed of 1 m/s were selected for evaluation in this section.

3.3.1. Result of U-Shaped Paths

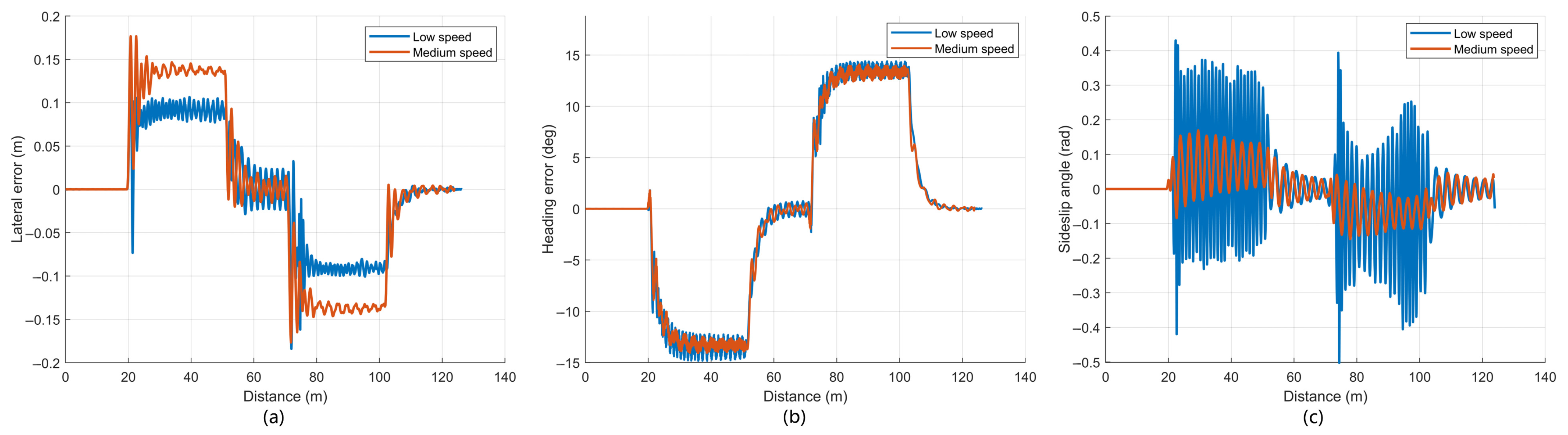

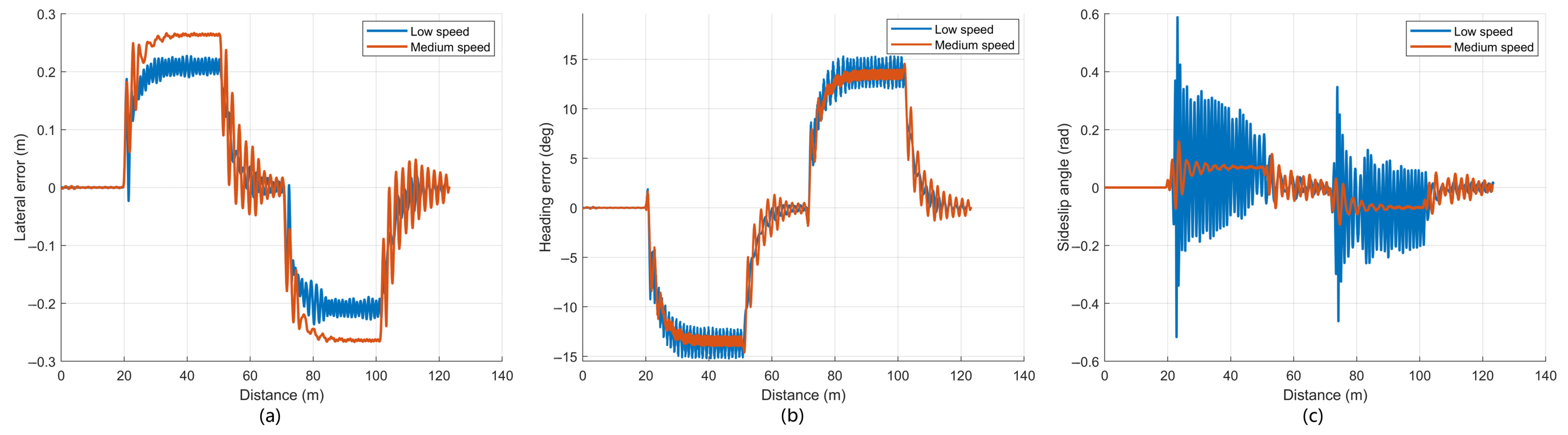

The U-shaped path is reused to evaluate the influence of turning speed on path-tracking performance, while the path geometry and other simulation settings remain unchanged. For each controller and each speed, the lateral error, heading error, and sideslip angle along the traveled distance are obtained. The results for SSA-MPC are shown in

Figure 6; those for MPC are shown in

Figure 7.

Table 5 summarizes the absolute mean value, standard deviation, and the absolute maximum value of lateral error.

For SSA-MPC in

Figure 6, the lateral and heading error curves at the two speeds exhibit similar evolution patterns, with error peaks concentrated in the curved sections and small residual errors on the straight segments. According to

Table 5, when the turning speed is low, the absolute mean lateral error, standard deviation, and absolute maximum values are 0.061 m, 0.074 m, and 0.183 m, respectively. At the medium speed, the corresponding values are 0.074 m, 0.068 m, and 0.221 m. For MPC in

Figure 7, the lateral and heading errors also show periodic peaks at each turn. The absolute mean, standard deviation, and absolute maximum lateral errors are 0.145 m, 0.172 m, and 0.226 m at low speed, and 0.136 m, 0.182 m, and 0.276 m at medium speed. In both controllers, the sideslip angle remains close to zero for most of the trajectory and exhibits pronounced fluctuations mainly in the curved segments, with larger amplitudes at the higher speed.

A direct comparison of the two controllers at the same speed indicates that SSA-MPC achieves consistently smaller lateral errors. At low speed, the absolute mean, standard deviation, and absolute maximum lateral errors of SSA-MPC are 0.061 m, 0.074 m, and 0.183 m, which are all smaller than those of MPC. At medium speed, the same trend is observed: 0.074 m, 0.068 m, and 0.221 m for SSA-MPC versus 0.136 m, 0.182 m, and 0.276 m for MPC. The sideslip angle curves in

Figure 6c and

Figure 7c further show that, at both speeds, SSA-MPC achieves smaller sideslip amplitudes and faster attenuation after each turn than MPC. Overall, for U-shaped paths, curve-velocity reduction benefits both controllers, and SSA-MPC maintains a clear advantage over MPC in terms of lateral error and sideslip suppression at both low and medium curving speeds.

3.3.2. Result of Rectangular-Shaped Paths

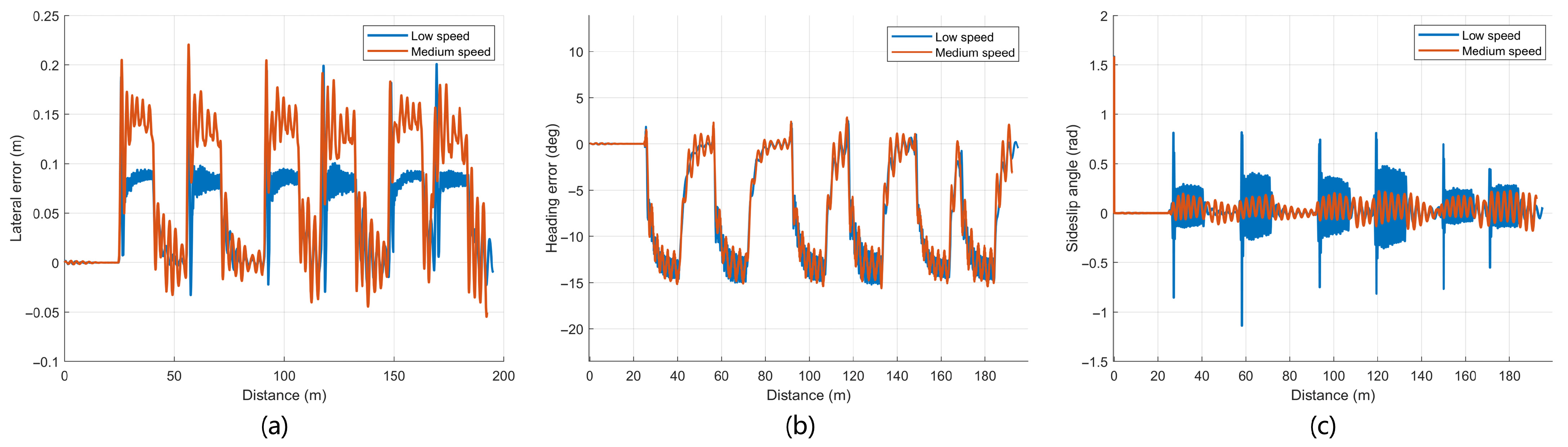

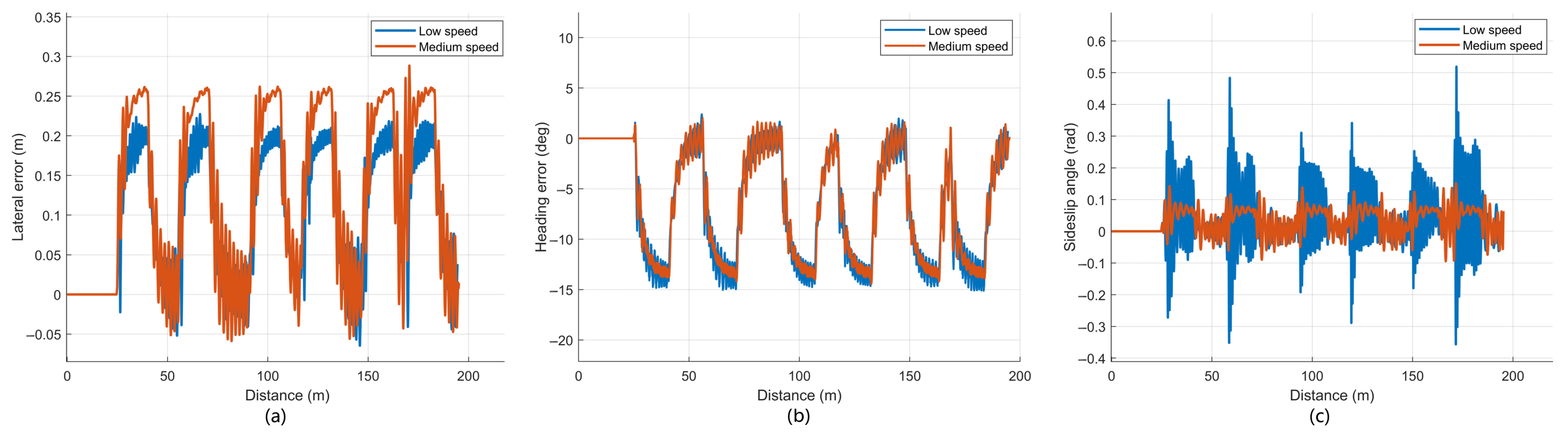

The rectangular-shaped path is further used as the reference path to evaluate the tracking performance in continuous same-direction turning scenarios under different turning speeds, while the path geometry and other simulation parameters remain unchanged. For each speed, the SSA-MPC and MPC controllers are applied under identical conditions. The responses of lateral error, heading error, and sideslip angle for SSA-MPC are shown in

Figure 8, those for MPC in

Figure 9, and the statistical indices of the lateral error are summarized in

Table 6.

Figure 8a and

Figure 9a show that, for both speeds and both controllers, the lateral error exhibits periodic peaks at each turn and small residual errors on the straight segments. According to

Table 6, for SSA-MPC, the mean value, standard deviation, and maximum value of the lateral error at low speed are 0.064 m, 0.036 m, and 0.204 m, respectively, and they increase to 0.074 m, 0.068 m, and 0.221 m at medium speed. For MPC, the corresponding indices are 0.135 m, 0.076 m, and 0.233 m at low speed and 0.131 m, 0.111 m, and 0.285 m at medium speed. The heading error curves in

Figure 8b and

Figure 9b follow a similar periodic pattern and the oscillate frequency of the heading error in SSA-MPC is smaller from the figure. The sideslip angle curves in

Figure 8c and

Figure 9c present repeated peaks around the cornering sections and smaller oscillations along the straight segments.

A quantitative comparison based on

Table 6 shows that SSA-MPC achieves consistently smaller lateral errors than MPC at both speeds. At low speed, the mean value, standard deviation, and maximum value of the lateral error with SSA-MPC are 0.064 m, 0.036 m, and 0.204 m, which were reduced by 52.6%, 52.6%, and 12.4%, respectively, compared to MPC with 0.135 m, 0.076 m, and 0.233 m. At medium speed, the corresponding reductions are 43.5%, 38.7%, and 22.5% derived from 0.074 m, 0.068 m, and 0.221 m versus 0.131 m, 0.111 m, and 0.285 m. The sideslip angle plots further show smaller peak amplitudes and faster attenuation for SSA-MPC than for MPC at both curving speeds. Overall, on the rectangular-shaped path, curve-velocity reduction benefits both controllers, and SSA-MPC maintains clear advantages in limiting lateral error and sideslip over the entire trajectory.

4. Discussion

The CG sideslip angle characterizes the deviation between the vehicle velocity vector and the body heading. Conventional kinematic models usually assume these two directions to be identical, an assumption that breaks down in tight corners or on low-adhesion surfaces. The simulation results indicate that, near the exits of bends on both U-shaped and rectangular-shaped paths, the conventional MPC exhibits pronounced understeer and oscillatory lateral error. By explicitly introducing the CG sideslip angle into the state equations, SSA-MPC enables the prediction model to represent more accurately the geometric relationship between the velocity direction and the heading angle. As a result, the vehicle tracks the reference path more tightly within the curves and eliminates steady-state offsets more rapidly after exiting the bends. The corresponding sideslip angle trajectories further show that SSA-MPC not only reduces the peak sideslip angle in most operating conditions, but also yields smoother convergence, indicating enhanced lateral stability while maintaining high path-tracking accuracy. This trend is consistent with recent dynamics-based studies that explicitly model tire sideslip to improve vehicle stability. The present work shows that even within a simplified kinematic framework, explicitly incorporating the CG sideslip angle into the model and state equations allows SSA-MPC to better capture the geometry between the velocity vector and vehicle heading, thereby realizing more accurate and more stable path tracking.

The simulations under different turning speeds further clarify the coupling among speed, sideslip angle, and model fidelity. It is generally accepted that reducing speed in curves improves safety and decreases instantaneous lateral deviation. Our results confirm that simply decreasing speed can significantly reduce peak lateral error and the overall error level. However, its effect on the average lateral error is limited when the model still neglects sideslip. When speed reduction is combined with explicit sideslip modeling, both the peak and overall lateral errors are further reduced. This indicates that, in large-curvature path tracking for agricultural machinery, poor field head-turning performance is caused not only by high speed but also by the mismatch between the simplified kinematic model and the actual vehicle dynamics. According to (22), even if remains constant, a reduction in increases the magnitude of the sideslip angle. The simulation results show that at low speed, the mean and standard deviation of the sideslip angle are higher than those at medium speed, yet the SSA-MPC still maintains smaller sideslip fluctuations, better convergence, and more accurate path tracking than the conventional MPC. This indicates that SSA-MPC exhibits stronger robustness and superior performance when sideslip effects are pronounced.

It should be noted that all simulations in this study are conducted for typical low-speed agricultural operations with forward velocities up to 3 m/s on level ground and with a spatially uniform tire–soil adhesion coefficient. These conditions match the validity range of the kinematic model with CG sideslip angle adopted here. At substantially higher speeds or on slippery and uneven terrain where strong load transfer, vertical dynamics, and rapid changes in tire forces occur, the assumptions underlying the kinematic model become less accurate. In such scenarios, the SSA-MPC framework is expected to remain applicable at the algorithmic level, but the prediction model would need to be upgraded to a dynamic vehicle model with nonlinear tire characteristics, and additional constraints related to tire forces may be required. Given that the proposed controller explicitly regulates the CG sideslip angle, it is anticipated to be particularly beneficial when sideslip effects are amplified by high speed or poor road conditions. However, this expectation must be confirmed by dedicated dynamic simulations and field tests under those operating conditions.

Regarding the transferability of the present results to real-field conditions, it should be noted that the controller is evaluated in a high-fidelity CarSim environment that captures vehicle dynamics and nonlinear tire behavior, but still assumes level terrain, homogeneous soil properties, and low-to-moderate operating speeds. Therefore, the quantitative values of lateral error and sideslip angle reported here cannot be directly extrapolated to practical field scenarios. However, the relative trend that SSA-MPC consistently achieves smaller lateral errors and reduced sideslip fluctuations than the conventional kinematic MPC is expected to remain valid in actual agricultural fields, where tire–soil interaction and sideslip effects are often more pronounced.

Several limitations of this study also point to directions for future work. In real vehicles, the CG sideslip angle cannot be measured directly and must be estimated online using integrated navigation sensors and state observers. Tufano et al. developed a nonlinear Kalman filter-based interacting multiple model (IMM) estimator to obtain accurate vehicle sideslip angle estimates under abrupt road-surface conditions change, using only low-cost onboard sensors [

25]. Integrating sideslip angle estimation methods, such as Kalman filtering or sliding-mode observers into the MPC loop, and systematically evaluating how estimation errors affect path-tracking performance and stability will be further studied. In addition, the effectiveness of the proposed controller has been demonstrated on a simulation platform, without fully accounting for nonlinear effects such as terrain undulation and load variations in actual fields. Deploying the proposed control scheme on embedded controllers of real agricultural machinery and conducting real-time performance assessment and field trials will be essential to verify its engineering feasibility.

5. Conclusions

This study tests the hypothesis that explicitly incorporating the vehicle’s center-of-gravity sideslip angle into the kinematic model improves path-tracking performance for agricultural vehicles. CarSim–Simulink co-simulation results demonstrate that, for both the U-shaped path typical of spraying operations and the rectangular path with sequential same-direction turns common in harvesting, the MPC formulation integrating the sideslip angle (referred to as SSA-MPC) consistently achieves visibly superior tracking accuracy compared to the MPC based on a conventional kinematic model that neglects sideslip (referred to as MPC), particularly during headland turns scenarios. Specifically, on the U-shaped path, SSA-MPC reduces the standard deviation of lateral error by 56.2% compared to MPC; on the rectangular path, the reduction is 53.2%. Tests at different speeds further confirm the effectiveness of SSA-MPC. For the U-shaped path, as speed increases, the standard deviation of lateral error decreases by 8.1% under SSA-MPC, while it increases by 5.8% under MPC. On the rectangular path, the standard deviation increases by 88.9% for SSA-MPC and by 46.0% for MPC as speed rises.

While previous studies suggest that sideslip may be negligible under small-curvature, high-adhesion conditions, these findings underscore its significant impact in scenarios with varying speeds and curvatures. Although SSA-MPC has demonstrated commendable performance in CarSim–Simulink co-simulation, parameter tuning and computational cost remain substantial challenges in transitioning from simulation to real-world application, which constitutes a key focus of our future work. Moreover, given the expanding application scenarios for autonomous agricultural machinery, it is imperative to improve the stability and precision of path-tracking algorithms under diverse curvature conditions and field-environment constraints. To this end, we are considering deep learning-enhanced MPC as a direction for our next study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and H.L.; methodology, B.C.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L. and Z.M.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, H.L.; data curation, B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, B.C.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, B.C. and Y.Z.; project administration, B.C.; funding acquisition, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32271999; the Frontier Technologies R&D Program of Jiangsu Province (Modern Agriculture), grant number BF2025312; the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, grant number PAPD-2023-87; and Open Funding from the Key Laboratory of Modern Agricultural Equipment and Technology (Jiangsu University), Ministry of Education, grant number MAET202301.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie, B.B.; Jin, Y.C.; Faheem, M.; Gao, W.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Jiang, H.K.; Cai, L.J.; Li, Y.X. Research progress of autonomous navigation technology for multi-agricultural scenes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 107963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Li, Q.S.; Ding, S.H.; Xing, G.Y.; Chen, L.P. Fixed-time generalized super-twisting control for path tracking of autonomous agricultural vehicles considering wheel slipping. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Ding, S.H.; Xia, J.; Xing, G.Y. Adaptive disturbance observer-based fixed time nonsingular terminal sliding mode control for path-tracking of unmanned agricultural tractors. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 246, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.B.; Cui, X.Y.; Wei, X.H.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.F. Design and testing of a tractor automatic navigation system based on dynamic path search and a fuzzy Stanley model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macenski, S.; Singh, S.; Martín, F.; Ginés, J. Regulated pure pursuit for robot path tracking. Auton. Robots 2023, 47, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, A.Z.; Wang, Y.F.; Wei, X.H. Straight-line path tracking control of agricultural tractor-trailer based on fuzzy sliding mode control. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.C.; Liu, Q.S.; Xu, H.H.; Yang, Z.; Hu, X.Y.; Song, Q.; Wei, X.H. Path Tracking Control of a Large Rear-Wheel–Steered Combine Harvester Using Feedforward PID and Look-Ahead Ackermann Algorithms. Agriculture 2025, 15, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Chen, L.Q.; Zheng, Q.; Dou, X.Y.; Yang, L. Control of a path following caterpillar robot based on a sliding mode variable structure algorithm. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 186, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.C.; Wei, X.H.; Liu, C.L.; Ge, J.Y.; Cui, X.Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, A.Z.; Chen, W.M. Adaptive path tracking and control system for unmanned crawler harvesters in paddy fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, R.; Deremetz, M.; Braconnier, J.B.; Thuilot, B.; Rousseau, V. Robust sideslip angles observer for accurate off-road path tracking control. Adv. Robot. 2017, 31, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.P.; Liu, G.; Luo, C.M. Path tracking control with slip compensation of a global navigation satellite system based tractor-scraper land levelling system. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 212, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, E.; Tang, Z.; Luo, C.M.; Xu, L.Z.; Wang, H. Trajectory prediction method for agricultural tracked robots based on slip parameter estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.X.; Man, Z.X.; Tu, T.P.; Yang, L.N.; Li, Y.Y.; Yi, Y.L.; Li, W.C.; et al. Path tracking control method and performance test based on agricultural machinery pose correction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.C.; Su, X.; Yu, H.J.; Guo, W.T.; Zhang, Q. Research on path tracking of articulated steering tractor based on modified model predictive control. Agriculture 2023, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahirpour, A.; Abel, D. Simulation and successive sideslip-compensating model predictive control for articulated dump trucks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3907–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Lee, J.H.; Han, K.S.; Choi, S.B. Vehicle path tracking control using pure pursuit with MPC-based look-ahead distance optimization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Hou, X.Q.; Hou, W.B. Composite path tracking control for tractor–trailer vehicles via constrained model predictive control and direct adaptive fuzzy techniques. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2017, 139, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.; Xue, J.L.; Chen, T.T.; Jiang, S. Robust trajectory tracking control of an autonomous tractor-trailer considering model parameter uncertainties and disturbances. Agriculture 2023, 13, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.; Borrelli, F.; Asgari, J.; Tseng, H.E.; Hrovat, D. Predictive active steering control for autonomous vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2007, 15, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Rother, C.; Chen, J. Event-Triggered Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking: Validation Using CARLA Simulator. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3547–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Rodriguez, A.A.; Manne, S.S.; Das, N.; Wallace, B. Comparison of kinematic and dynamic model based linear model predictive control of non-holonomic robot for trajectory tracking: Critical trade-offs addressed. In Proceedings of the IASTED International Conference on Mechatronics and Control, Anaheim, CA, USA, 6–7 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Niu, C.H.; Wang, Z.F.; Jiang, Y.X.; Jian, J.M.; Tang, X.Y. Model and parameter adaptive MPC path tracking control study of rear-wheel steering agricultural machinery. Agriculture 2024, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevly, D.M.; Ryu, J.; Gerdes, J.C. Integrating INS sensors with GPS measurements for continuous estimation of vehicle sideslip, roll, and tire cornering stiffness. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2006, 7, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Hashemi, E.; Xiong, L.; Khajepour, A.; Xu, N. Autonomous vehicles sideslip angle estimation: Single antenna GNSS/IMU fusion with observability analysis. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 14845–14859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, F.; Lui, D.G.; Battistini, S.; Brancati, R.; Lenzo, B.; Santini, S. Vehicle Sideslip Angle estimation under critical road conditions via nonlinear Kalman filter-based state-dependent Interacting Multiple Model approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 146, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |