1. Introduction

In recent years, deep learning (DL) has advanced at an extraordinary pace and has been successfully deployed across a wide spectrum of application domains [

1,

2,

3]. These advancements are largely driven by the intrinsic flexibility of deep learning models and their strong capability for hierarchical feature representation. Although architecture fundamentally governs model performance, designing optimal structures remains a challenge. It entails the meticulous specification of hyperparameters—including layer types and dimensions—that dictate the model’s efficiency and generalization capabilities. As neural networks become increasingly deep and complex, the design of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) requires accounting for an expanding set of considerations, while the availability of large-scale datasets such as ImageNet [

4] further amplifies the cost of manual trial-and-error exploration. Against this backdrop, neural architecture search (NAS) has emerged as a promising research direction and has garnered substantial attention within the deep learning community [

5,

6,

7]. The central aim of NAS is to automate the construction of neural network architectures, thereby reducing human intervention and discovering architectures that surpass those crafted through manual design.

Popular NAS approaches typically construct a predefined search space that enumerates all candidate architectures, and then employ heuristic search strategies to identify an optimal design. Early mainstream methods largely relied on evolutionary algorithms (EAs) and reinforcement learning (RL) as the primary optimization paradigms.

By optimizing an recurrent neural network (RNN) controller with reinforcement learning, Zoph et al. [

8] achieved a remarkable 96.35% accuracy on CIFAR-10. Other notable RL-based contributions include MetaQNN by Baker et al. [

9], which adopts greedy search, and BlockQNN by Zhong et al. [

10], which focuses on block-structured spaces.

In the domain of evolutionary algorithms, NasNet [

11] systematically eliminates underperforming architectures during the search process. In addition, So, D et al. [

12] introduced an evolutionary Transformer framework, and Real et al. [

13] ensured population diversity through regularized evolution.

However, traditional architecture search strategies employing Bayesian optimization [

14], evolutionary computation, or reinforcement learning invoke prohibitive computational costs. For instance, obtaining a state-of-the-art architecture may require 2000 GPU-days using reinforcement learning [

15] or 3150 GPU-days using evolutionary algorithms [

13]. To address the issue of computational cost, Liu. et al. proposed Differentiable architecture search [

16] (DARTS). DARTS relaxes the discrete architecture representation into a continuous search space and optimizes validation performance directly via gradient descent, slashing the computational overhead from thousands of GPU-days to merely a few GPU-hours.

In recent years, DARTS has rapidly established itself as a mainstream paradigm for the automated design of deep neural network architectures [

17]. Despite its remarkable efficiency, subsequent studies have identified several limitations of DARTS.

Depth Gap Problem: K. Yu et al. [

18] pointed out that the discrepancy in network depth between the search phase (shallow) and the evaluation phase (deep) can lead the original DARTS to perform no better than, and sometimes even worse than, random search.

Performance Collapse and Skip-Connection Dominance: Studies have shown that due to the cumulative advantage of parameter-free operations, the final architectures are often dominated by skip connections, resulting in severe performance degradation [

19].

To address these issues, researchers have proposed various solutions, including mitigating the dominance of skip connections [

20]. By introducing a regularization term, S. Movahedi et al. [

21] aimed to mitigate collapse through the harmonization of cell operations. Similarly, a collaborative competition technique was employed by Xie, W.S. et al. [

22] to improve perturbation-based architecture selection. Additionally, Huang et al. [

23] investigated the efficacy of DARTS in super-resolution scenarios. Luo et al. [

24] introduced hardware-aware SurgeNAS to alleviate memory bottlenecks, while Li et al. [

25] employed a polarization regularizer to discover more effective models.

Although DARTS represents a major breakthrough in search efficiency, it still faces severe memory bottlenecks when dealing with high-dimensional search spaces. To further enhance search efficiency and reduce dependence on hardware resources, extensive research has focused on lightweight design and memory optimization. To address the issue of excessive memory consumption, PC-DARTS [

26] introduced a Partial Channel Connections strategy. By sampling and selecting operations on only a subset of channels during the search process, this method significantly improves memory utilization efficiency [

27]. Such a design not only greatly reduces computational cost but also enables the use of larger batch sizes under the same hardware constraints, thereby improving search stability. To mitigate the potential information loss caused by channel sampling, Y. Xue et al. [

28] incorporated the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [

29] into the architecture search. Shu Li et al. proposed DLW-NAS [

30], which designs a differentiable sampler on top of a super-network to avoid exhaustively enumerating all possible sub-networks [

27].

To address the aforementioned issues, we propose an efficient and lightweight differentiable architecture search method (EL-DARTS). In the design of the search space, redundant operations in DARTS are removed and a partial-channel strategy is adopted to reduce memory consumption, thereby substantially improving search efficiency. During architecture modeling, Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy is introduced to enhance the stability of the architecture parameters, alleviate the overuse of skip connections, and ensure fair competition among different candidate operators. In addition, an entropy-based regularization term is incorporated into the loss function to sharpen the distribution of architecture parameters, which accelerates search convergence and reduces the risk of becoming trapped in suboptimal local minima. Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

A lightweight neural architecture search algorithm is presented that preserves accuracy while substantially reducing parameter count and search time.

A FLOP-, parameter-, and latency-driven pruning strategy streamlines the conventional DARTS search space by removing redundant and computationally expensive operators, yielding a more compact operation set that improves both search efficiency and stability.

A Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy is employed to suppress the early dominance of skip connections—resulting from their parameter-free nature—and to promote fair competition among all candidate operators.

A progressively enhanced entropy-based regularization term is incorporated to sharpen the distribution of architecture parameters, accelerating operator differentiation, stabilizing structure selection during discretization, and reducing final accuracy degradation.

EL-DARTS effectively mitigates the excessive dominance of skip connections, accelerates operator differentiation, and achieves a superior balance between efficiency and performance compared with DARTS on both CIFAR-10 and ImageNet. Specifically, we achieved an error rate of 2.47% within less than 0.1 GPU-days (approximately 1.8 h) on a single GTX 1080 Ti, substantially surpassing the 3.15% error rate reported by DARTS, which requires 1.0 GPU-day for its search process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Principle of DARTS

DARTS [

16] formulates the neural architecture search space as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where edges represent candidate operations from a predefined set

. To enable gradient-based optimization, the discrete selection of operations is relaxed into a continuous search space using a SoftMax distribution over learnable architecture parameters

. For an edge

, the mixed operation

is computed as:

where

is the input feature map, and

denotes a candidate operation from the search space

.

The search process is modeled as a bilevel optimization problem, where the goal is to find the optimal

that minimizes the validation loss

, subject to the constraint (denoted as

) that the

denotes the network weights, and

represents the optimal weights obtained by minimizing the training loss

:

After the search phase, the final discrete architecture is derived by selecting the operation with the highest value for each edge. While efficient, this standard formulation suffers from memory bottlenecks and instability, which we address in the following sections.

2.2. Lightweight Methods

2.2.1. More Efficient Search Space

The conventional DARTS search space typically includes eight fundamental operators. To clarify the notations used in this paper, we define the shortcuts used for these operations: none represents the zero operation (indicating no connection between nodes), max_pool denotes Max Pooling, avg_pool denotes Average Pooling, skip_connect represents an identity mapping (direct connection), sep_conv stands for Depthwise Separable Convolution, and dil_conv refers to Dilated Convolution. The suffixes (e.g., 3 × 3, 5 × 5) indicate the kernel size. The complete set includes: none, max_pool_3 × 3, avg_pool_3 × 3, skip_connect, sep_conv_3 × 3, sep_conv_5 × 5, dil_conv_3 × 3, and dil_conv_5 × 5. Although these operators offer diverse combinatorial possibilities for network architecture design, they exhibit substantial functional redundancy. In particular, the multiple SepConv operators with different kernel sizes, together with pooling-based operators, provide only limited differences in representational capability while significantly increasing the redundancy of the search space. Moreover, the computational costs of candidate operators exhibit significant disparities. For instance, parameter-free operations like skip connections and pooling incur negligible overhead, whereas large-kernel convolutions require substantially higher FLOPs and latency. This asymmetry skews the search process toward low-cost operators, destabilizing the optimization of architectural parameters and leading to degenerate solutions, typically networks dominated by skip-connections.

For mobile or lightweight application scenarios, the practical benefits of certain operators are limited, and some may even increase inference latency and energy consumption. As described in VGG [

31], two 3 × 3 convolutions require fewer parameters and FLOPs than a single 5 × 5 convolution, while yielding comparable performance. Moreover, NAS-Bench-201 [

32], a standard benchmark suite in the neural architecture search (NAS) field, also excludes 5 × 5 and 7 × 7 convolutional operations. Therefore, following the design principles adopted in VGG and NAS-Bench-201, we discard the high-FLOP operators used in DARTS. After measuring the latency of each operator on the target platform (as shown in

Figure 1) and making an overall assessment, we select

sep_conv_3 × 3,

max_pool_3 × 3,

skip_connect, and

dil_conv_3 × 3 as the fundamental operators. This reduces redundancy in the search space and improves search efficiency.

The overall framework is illustrated in

Figure 2. On the left, input1 and input2 denote the input nodes of the cell, while output represents the cell’s output node, and Node0–Node3 are the intermediate nodes. The black edges indicate mixed operations, with each edge containing four candidate operators (

skip_connect,

sep_conv_3 × 3,

max_pool_3 × 3, and

dil_conv_3 × 3). The direction of the arrows reflects the flow of information (i.e., the inputs to Nodes 0–3). The four blue lines represent the channel concatenation that forms the final output of the cell. The diagram on the right depicts the macro-level architecture during the search phase, where the green arrows indicate that the outputs of preceding cells serve as the inputs to subsequent cells.

2.2.2. More Efficient Training Process

To improve training efficiency in terms of GPU memory utilization, this study adopts the partial channel connection strategy proposed in PC-DARTS [

26]. Specifically, to effectively reduce memory overhead and computational cost while maintaining high search performance, the feature channels c of each edge are divided into two separate branches. One subset of channels is directed to the Operation Selection Block, where different candidate operations are evaluated during the architecture search. The remaining channels—referred to as the masked part—are directly propagated to the output, preserving the input feature information through an identity mapping and thereby maintaining feature consistency across layers.

After the operation selection process, the outputs from both branches are concatenated and processed by a Channel Shuffle operation to facilitate inter-channel information exchange and feature fusion. This operation effectively mitigates the information fragmentation problem introduced by channel partitioning, ensuring that the resulting architecture maintains strong complementarity and connectivity in feature representation.

Unlike conventional DARTS, which performs operation selection over all feature channels, PC-DARTS and our method apply the search process only to a subset of channels, significantly reducing computational and memory demands during the search phase. This improvement enables neural architecture search to scale to larger networks and more complex datasets. Meanwhile, the channels excluded from the search still participate in feature propagation via identity mapping, which enhances training stability and generalization capability, preventing performance degradation caused by over-optimization.

2.3. Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy

In the original DARTS framework, each edge performs a SoftMax normalization over the architecture parameters corresponding to all candidate operations, forming a mixed operation. However, this mechanism introduces a clear unfair competition problem during optimization. Specifically, the skip-connection tends to dominate the search process due to its parameter-free nature, shorter gradient propagation path, and higher sensitivity to training loss reduction. Consequently, it rapidly accumulates advantages in the early search stages, leading to significantly larger SoftMax weights compared to other operations. This phenomenon, known as skip-connection dominance, causes the searched architectures to become overly simplified in later stages, thereby limiting their representational capacity.

Moreover, DARTS implicitly assumes that all incoming edges to a given node contribute equally to feature aggregation. In practice, however, the importance of different edges varies dynamically throughout training. When all edges are treated with equal importance, potentially valuable connections may suffer from persistent gradient disadvantages, preventing them from being adequately activated. As a result, the diversity and robustness of the final genotype are substantially reduced.

To address these issues, we propose a Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy (DCSS) that introduces learnable, dynamically adjusted weighting coefficients at the edge level. This mechanism enables adaptive modeling of the relative importance of different input edges. By decoupling these dynamic coefficients from the architecture parameters during optimization, the proposed strategy allows the model to flexibly adjust edge importance according to the training dynamics.

Specifically, for all incoming edges

connected to a node

within a cell, we first initialize a set of random coefficients

drawn from a uniform distribution:

These coefficients serve as the initial dynamic weights that reflect the relative importance of each edge. Subsequently, a SoftMax normalization is applied to obtain the normalized weight of each edge

:

The output of a node

can be expressed:

Here, denotes the set of candidate operations. This design introduces a two-level learnable weighting mechanism: the outer-level coefficient is used to adjust the relative importance of different edges, while the inner-level is applied to differentiate among the candidate operators within each edge.

During the training phase, is dynamically updated through the back-propagation of the loss function. In the initial stages, the edge weights exhibit minimal variance, which enables the model to adequately explore diverse connectivity patterns within a broad search space. As training progresses, the edge weights gradually reflect their actual contribution to task performance, leading to the attenuation of weights corresponding to ineffective or redundant connections, while reinforcing those with robust feature transmission capabilities.

The primary benefit of this approach is achieved by explicitly introducing a normalized edge weight between nodes. Consequently, the contribution of the skip operation no longer solely relies on its parameter-free nature; instead, it must compete with other operators under the same distribution, thereby mitigating the issue of unbounded growth typically associated with skip connections. Simultaneously, the dynamic adjustment opportunities afforded to different input edges during training result in a more balanced operator distribution, which effectively reduces the oscillation and collapse phenomena observed in the architectural parameter . This dynamic coefficient enhances the network’s exploratory capacity during the early training phase, leading to the generation of a greater number of differentiated yet performance-similar candidate architectures during the discretization stage, ultimately improving the model’s transferability across various tasks.

It is noteworthy that, unlike strategies such as Fair-DARTS [

33] which enforce fairness through gradient clipping or weight projection, the proposed method achieves a “soft constraint” balance via the adaptive evolution of

, eliminating the need for explicit modifications to the architectural parameter gradients. This characteristic results in minimal computational overhead and facilitates easy implementation. Furthermore, the dynamic coefficient scheduling mechanism and the subsequent entropy regularization term are complementary in their optimization granularity: the former regulates the balance of feature flow at the edge level, while the latter promotes the sharpening of operator weights at the operation level. The synergistic effect of these two components collectively enhances the convergence and stability of the search process.

2.4. Entropy Regularization

In the late stages of the search, the tendency of the multi-operator weight distribution to become smooth may result in the discarding of potentially effective operations during the final discretization phase (i.e., genotype extraction). This ambiguity often leads to performance degradation and instability in the derived model. To mitigate this issue, we introduce an Entropy Regularization term. This mechanism is designed to constrain the distribution entropy of the operator weights on each edge, compelling it to gradually decrease during the latter part of training.

To further control this sharpening process effectively, we incorporate a Temperature Annealing strategy. Instead of utilizing the standard SoftMax function, we formulate the entropy calculation based on a temperature-scaled probability distribution. For the architectural parameters

associated with a single edge, the temperature-scaled probability

is defined as:

where

is the temperature coefficient that controls the sharpness of the distribution. Based on this probability distribution, the entropy

for a given edge is formally defined as:

A higher

yields a softer distribution (high entropy) suitable for broad exploration in the early phase, while a lower

leads to a sharper distribution (low entropy) for precise exploitation in the later phase. To achieve a progressive sharpening effect, we employ an exponential decay schedule for

with a lower bound limit:

where

denotes the current epoch,

= 5.0 is the initial temperature,

= 0.95 is the decay factor, and

= 0.5 serves as the clipping threshold to prevent numerical instability.

Let

denote the network weights. Given the original validation loss

, the total loss function

incorporating the temperature-aware entropy regularization is formulated as:

where

is the regularization weight coefficient. In our experiments,

is set to a constant value of 0.001 to maintain a consistent regularization strength. This combined strategy forces the model to gradually favor deterministic architectural selection, thereby mitigating the randomness and the risk of overfitting during the search phase. Conceptually, this approach resonates with the inverse of the Maximum Entropy Principle in information theory, where certainty in model decisions is reinforced by minimizing entropy. Furthermore, relevant studies [

34] have demonstrated that reducing the entropy of the architectural parameters effectively enhances structural consistency and search reproducibility during the discretization phase.

Finally, incorporating the efficient search space, dynamic coefficient scheduling, and entropy regularization, the overall training procedure of EL-DARTS during the search phase is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: EL-DARTS Search Phase Optimization |

Input: Training data

Initialize weights , parameters , , temperature while not converged do:

Update according to

For each mini-batch do

and generate channel mask M.

searches for the best structure

and generate channel mask M.

trains for that structure using .

End for

End while

Output: Derive the final discrete architecture (Genotype) |

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Setup and Datasets

The experiments were conducted on an environment running Ubuntu 22.04 (Canonical Ltd., London, UK) and utilizing an NVIDIA GTX 1080 Ti GPU(NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The programming environment was Python 3.10 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA), powered by the PyTorch 2.1.0 (Meta Platforms Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) deep learning framework (on Ubuntu 22.04). Two standard datasets commonly used for evaluating Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods—CIFAR-10 and ImageNet [

4]—were employed for image classification.

CIFAR-10: This dataset contains 10 object classes with 6000 images per class, amounting to 60,000 images in total. All images are RGB formatted with a resolution of 32 × 32. We follow the standard split, utilizing 50,000 images for model training and the remaining 10,000 for evaluation.

ImageNet: The ImageNet dataset serves as a large-scale benchmark, covering 1000 distinct object classes. It provides a training set of approximately 1.28 million images and a validation set of 50,000 images. The dataset features high-resolution data that is maintained with a roughly balanced distribution among the categories.

Consistent with the standard practice of DARTS, the architecture search process was carried out on CIFAR-10, and the derived architecture was subsequently evaluated on both CIFAR-10 and ImageNet. For the ImageNet evaluation, we adopt the Mobile Setting, where the input image size is fixed at 224 × 224 and the total number of Multi-Add Operations (often denoted as MACs or FLOPs) is constrained to less than 600 M. A comprehensive set of experiments was performed to assess the proposed method, utilizing Test Error (%), the number of Parameters (Param), and Search Cost (GPU-Days) as the primary evaluation metrics.

3.2. Results on CIFAR-10

Our training configurations largely adhere to the settings established by DARTS. During the architecture search stage, we build a supernet consisting of eight cells (two reduction and six normal cells), where each cell contains = 6 nodes. The search process runs for 50 epochs with an initial channel width of 16. To perform bi-level optimization, we partition the 50,000 CIFAR-10 training images into two equal halves: the first half is utilized to optimize the model weights (w), while the second is reserved for updating the architecture parameters (). We adopt the partial connection strategy, setting the sampling ratio to K = 4, meaning only 1/4 of the operations are sampled for feature transmission on each edge. Due to the high memory consumption of full channel connections, the original DARTS is limited to a batch size of 64. In contrast, our memory-efficient strategy allows us to increase the search phase batch size to 256, which improves the stability of the optimization process. The network weights (w) are optimized using SGD with momentum (0.9), an initial learning rate of 0.1 (annealed to zero using a cosine schedule without restarts), the entropy regularizer is initialized with a coefficient of 0.001, and a weight decay of 3 × 10−4. Benefiting from the increased batch size, the entire search process takes only 1.8 h on a single NVIDIA GTX 1080 Ti GPU for CIFAR-10.

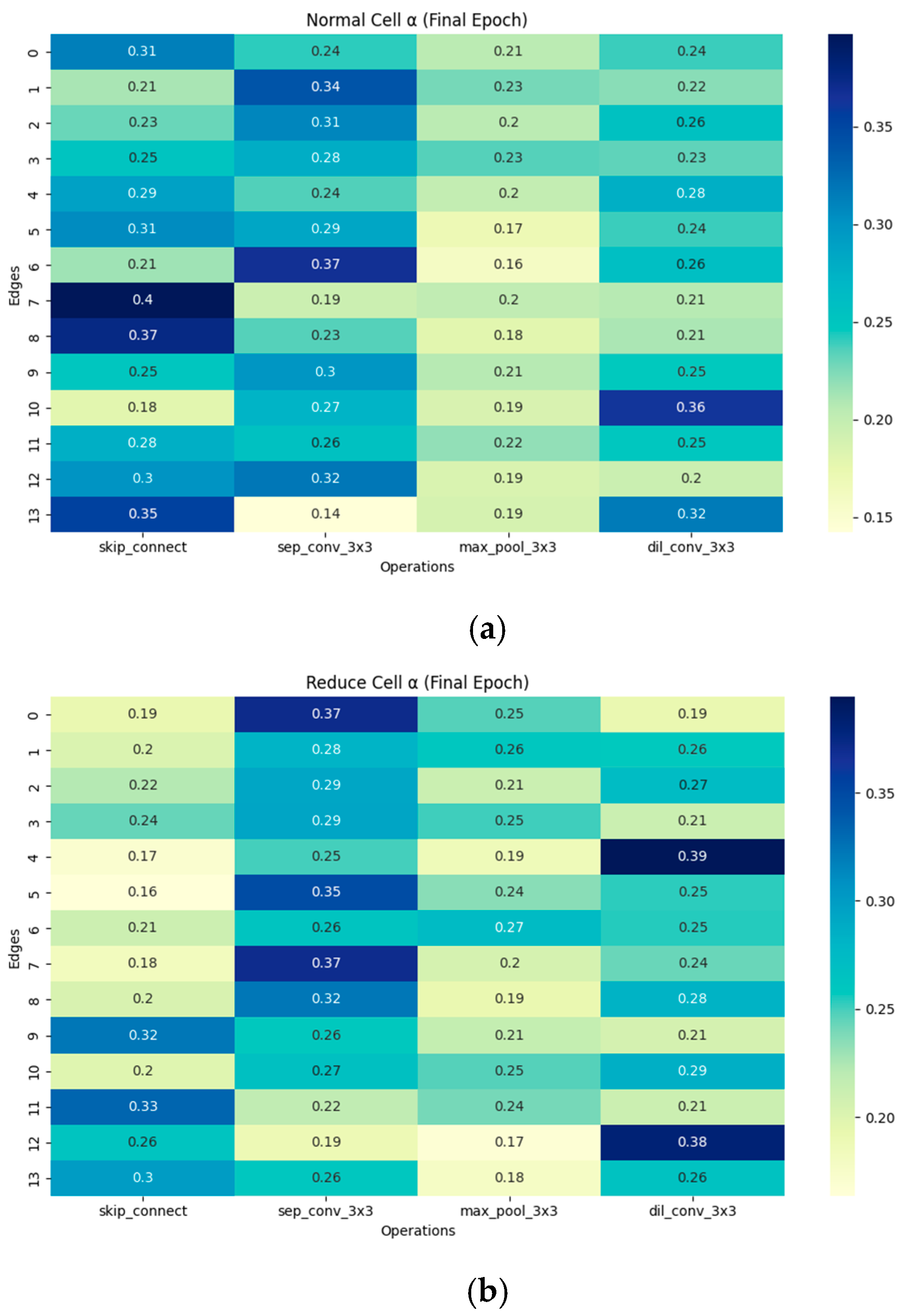

Regarding the results obtained from the search conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset, the heatmap of the architectural parameters

is presented in

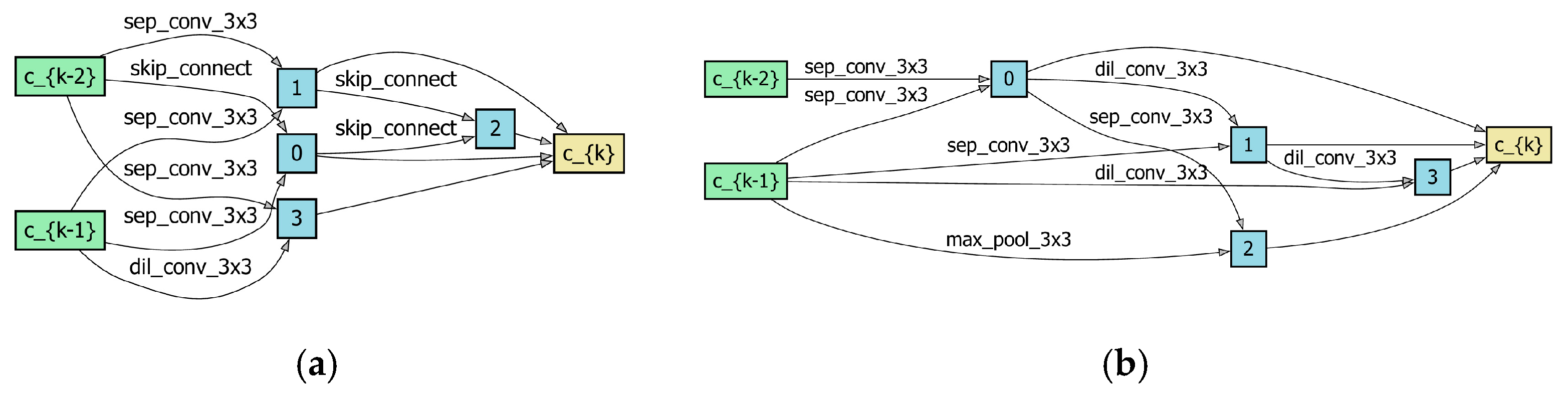

Figure 3, and the resulting cell architectures (Normal and Reduction Cells) are displayed in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, the final normal cell contains only 2 skip-connections out of 8 edges. This stands in contrast to collapsed architectures often observed in standard DARTS, where skip-connections can occupy the majority of the edges. This structural balance confirms that our Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy effectively alleviates skip-connection dominance.

To ensure a fair comparison, our evaluation phase adheres strictly to the standard DARTS framework. The constructed network comprises a stack of 20 cells, consisting of 18 Normal Cells and 2 Reduction Cells, where all cells of a given type employ the same discovered topology. We set the initial channel count to 36 and train the model from scratch for 600 epochs using the complete set of 50,000 training images. We employ the SGD optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.025 (annealed to zero via a cosine schedule without restarts), a momentum of 0.9, and a weight decay of 3 × 10

−4. The comparative results are presented in

Table 1.

Note: #ops denotes the number of candidate operations. The reported Search Cost represents the GPU-days required for the architecture search phase only. It does not include the cost of the final retraining (evaluation) phase.

Analysis of the CIFAR-10 search results demonstrates that EL-DARTS achieves a superior performance–cost balance. Most notably, its search cost is the lowest among all compared algorithms at just 0.075 GPU days, representing a twofold acceleration over the PC-DARTS baseline. Despite this extreme efficiency, EL-DARTS maintains highly competitive performance, yielding a test error of 2.47%, which is superior to leading methods like DARTS and PC-DARTS. Furthermore, the resulting architecture is highly compact, featuring only 3.1 M parameters. Collectively, these results confirm that EL-DARTS successfully pushes the efficiency frontier of differentiable architecture search while ensuring top-tier performance.

3.3. Results on ImageNet

To validate the transferability of the discovered architecture, we further conducted evaluation experiments on ImageNet. The evaluation network was constructed in a manner consistent with the DARTS algorithm, specifically: the network depth d was set to 14, the initial number of channels

to 48, and the network was trained for 250 epochs. Adhering to the constraints of the DARTS algorithm, we selected models for comparison that meet the mobile device operational requirements, specifically those architectures where the number of multiply–accumulate operations (MACs) is less than 600 M when the input resolution is 224 × 224. The performance of our architecture, along with the architectures obtained by comparison algorithms, is presented in

Table 2.

Analysis of the ImageNet evaluation results demonstrates that EL-DARTS achieves a superior performance–efficiency trade-off compared to its peers. Most notably, its search cost is the absolute lowest among all comparison architectures, requiring only 0.075 GPU days. This represents a significant acceleration over its gradient-based baselines, such as PC-DARTS (0.1 GPU days) and the original DARTS (4.0 GPU days). Concurrently, EL-DARTS yields a competitive Top-1 error rate of 26.2% and a Top-5 error rate of 8.0%, surpassing the performance of both DARTS (26.7%) and NASNet-A (26.0%).

3.4. Ablation Study

To rigorously validate the independent contribution and synergistic effect of our three proposed innovative components on the final architectural performance and search efficiency, we conduct a detailed ablation study on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Our full proposed method is built upon the established Partial Connection baseline (X) derived from PC-DARTS, integrating the following three novel points:

A: Efficient Search Space (ESS).

B: Dynamic Coefficient Scheduling Strategy (DCSS).

C: Entropy Regularization (ER).

Our ablation focuses on systematically removing each novel component from the Full Model to quantify its specific impact on the key performance metrics. Each algorithm was run three times on CIFAR-10, and the results are summarized in

Table 3. When all three components are disabled, the model exhibits the worst performance. As the components are progressively enabled, the test error decreases consistently. Notably, activating components A and B together, or enabling all components (A, B, and C), leads to substantial accuracy gains, with the full configuration achieving the lowest test error of 2.47%. Moreover, incorporating additional components does not significantly increase the search cost, which remains around 0.075 GPU days for most settings. These results indicate that the proposed designs improve performance while maintaining high search efficiency. Overall, each component contributes positively to performance, and their combined effect yields the best results.