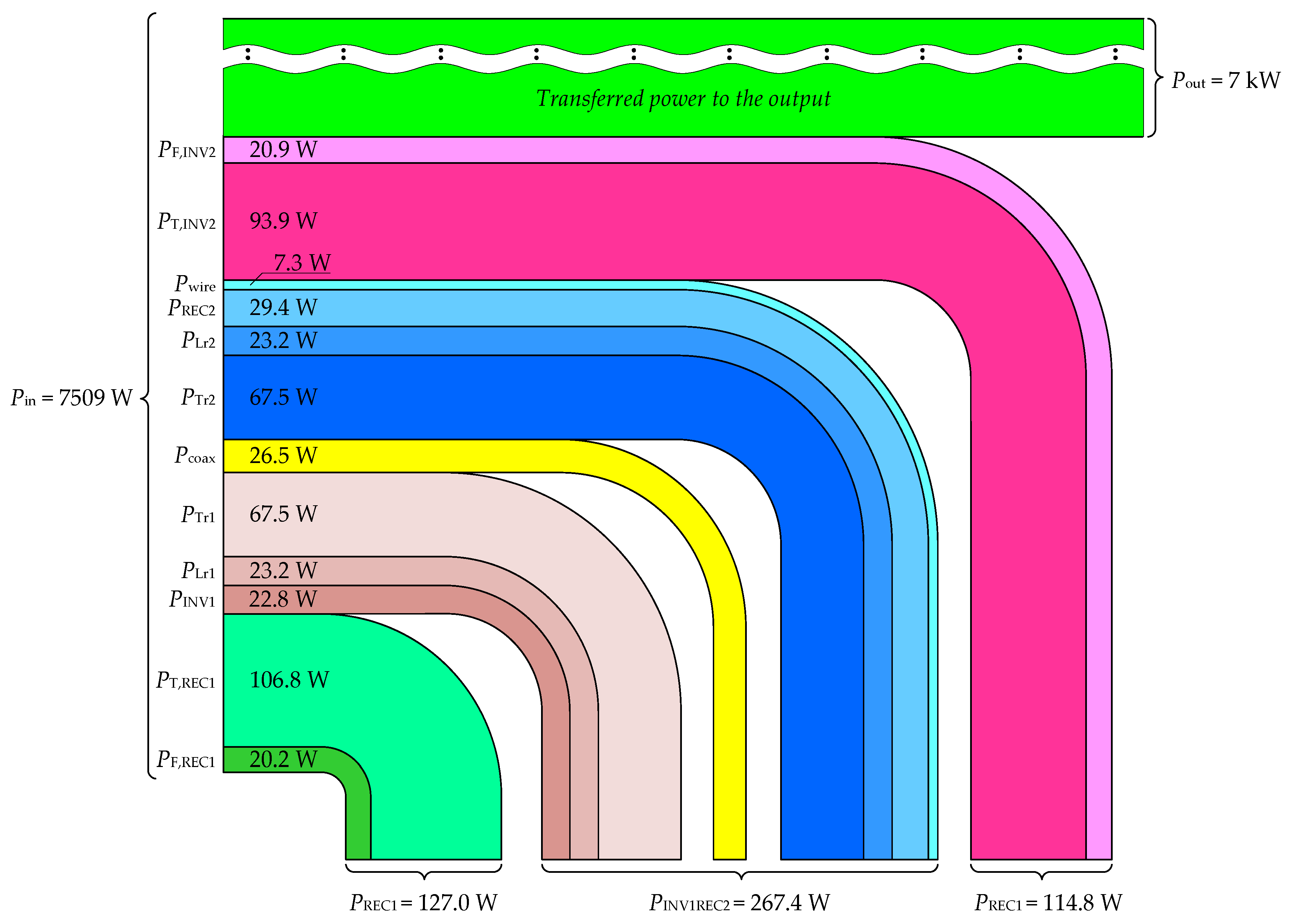

Power Losses of the High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable Energy Transfer System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A complete modeling framework for the medium-frequency energy-transfer system, including all converters and passive components, enabling system-level analysis.

- (2)

- A comprehensive loss analysis covering semiconductors, inductors, transformers, and the medium-frequency cable, identifying dominant loss mechanisms and their impact on natural-cooling operation constraints.

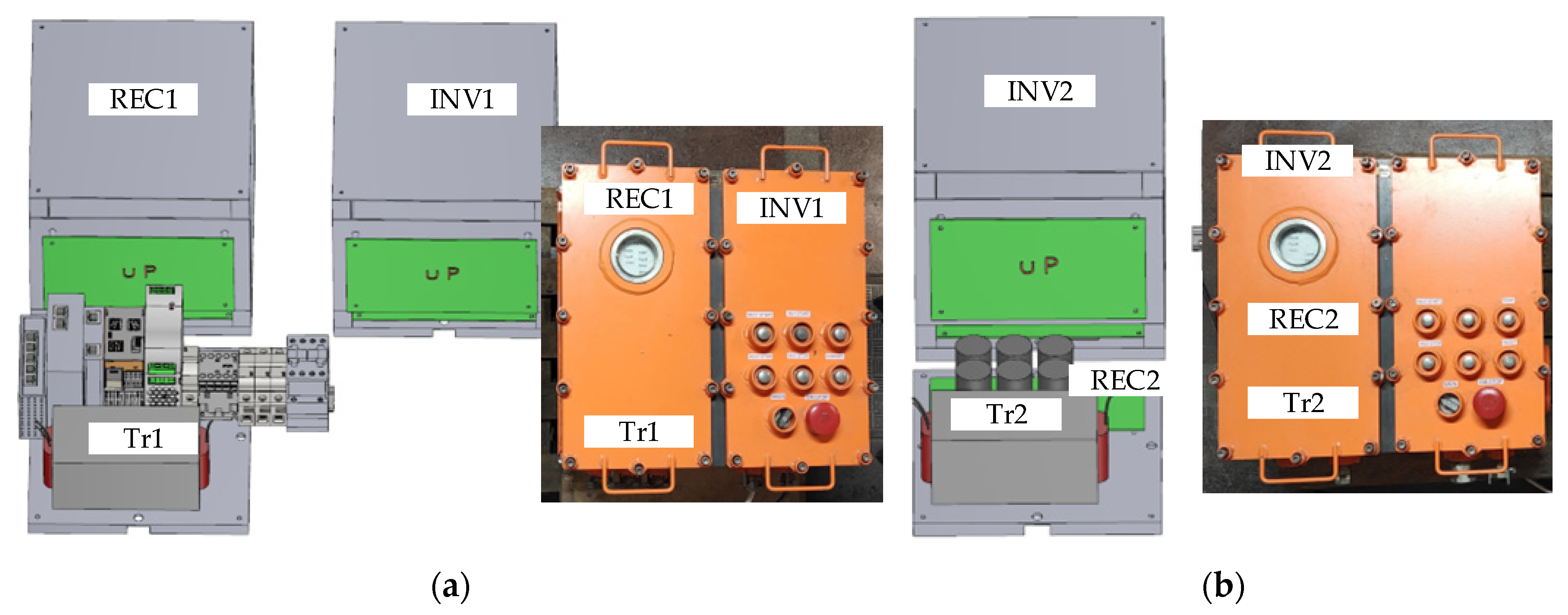

2. Description of the System

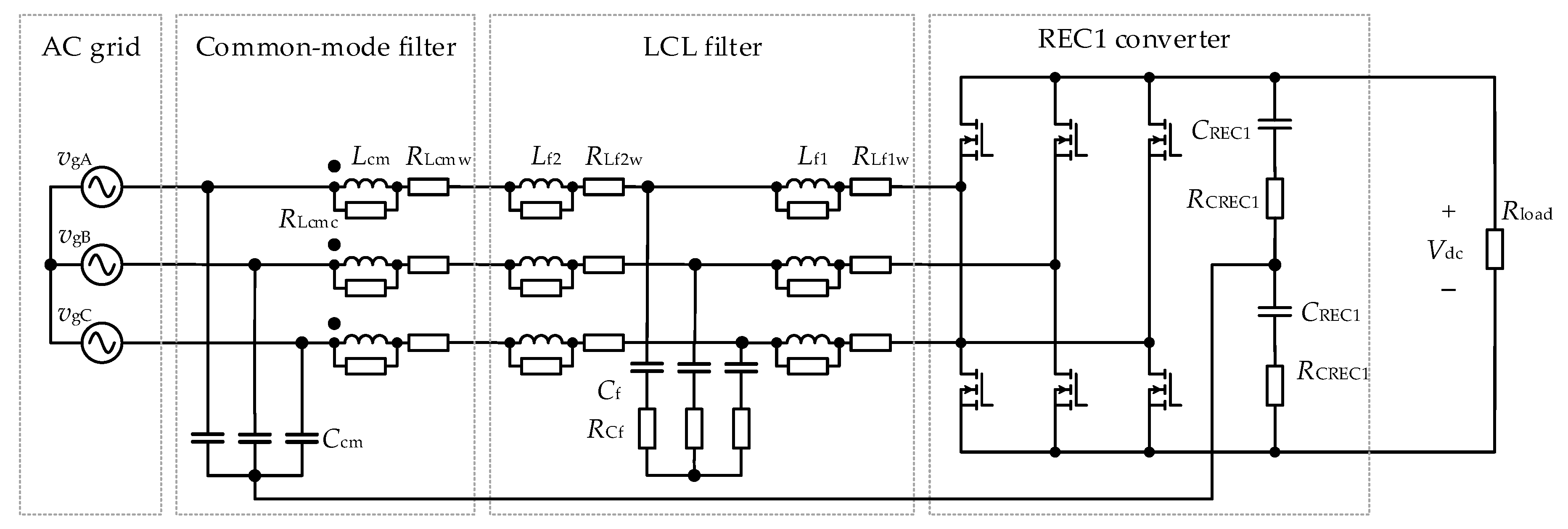

- REC1 is a grid-tied three-phase converter operating as a rectifier with a power factor close to unity. The converter is equipped with an LCL-type AC filter, whose general design principles for grid-connected applications are described in [22,23], while the detailed design methodology of the specific LCL filter used in this work is presented in publication [24]. The converter operates at a switching frequency of 50 kHz. For a grid line-to-line voltage of 500 V, the output DC-link voltage is set to 760 V and can be increased up to 870 V.

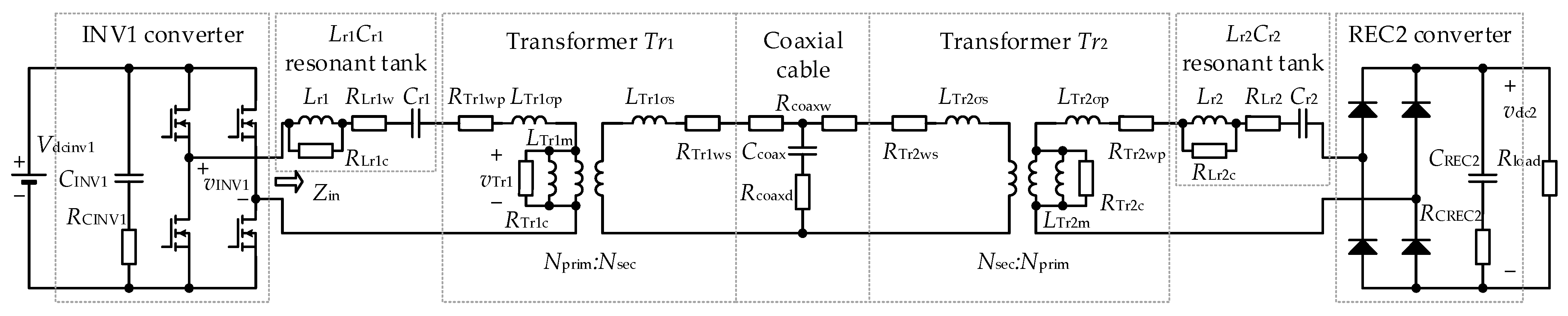

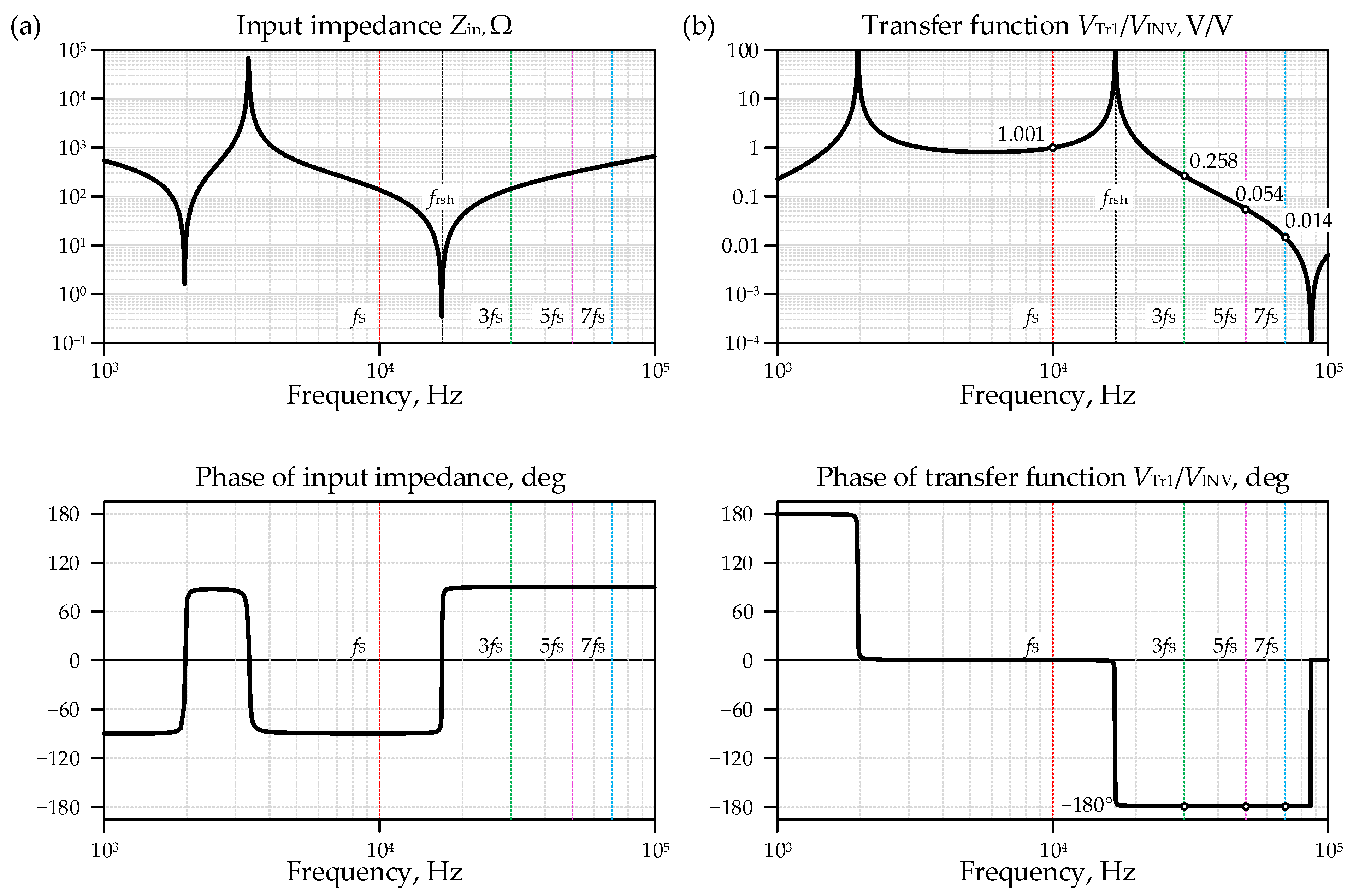

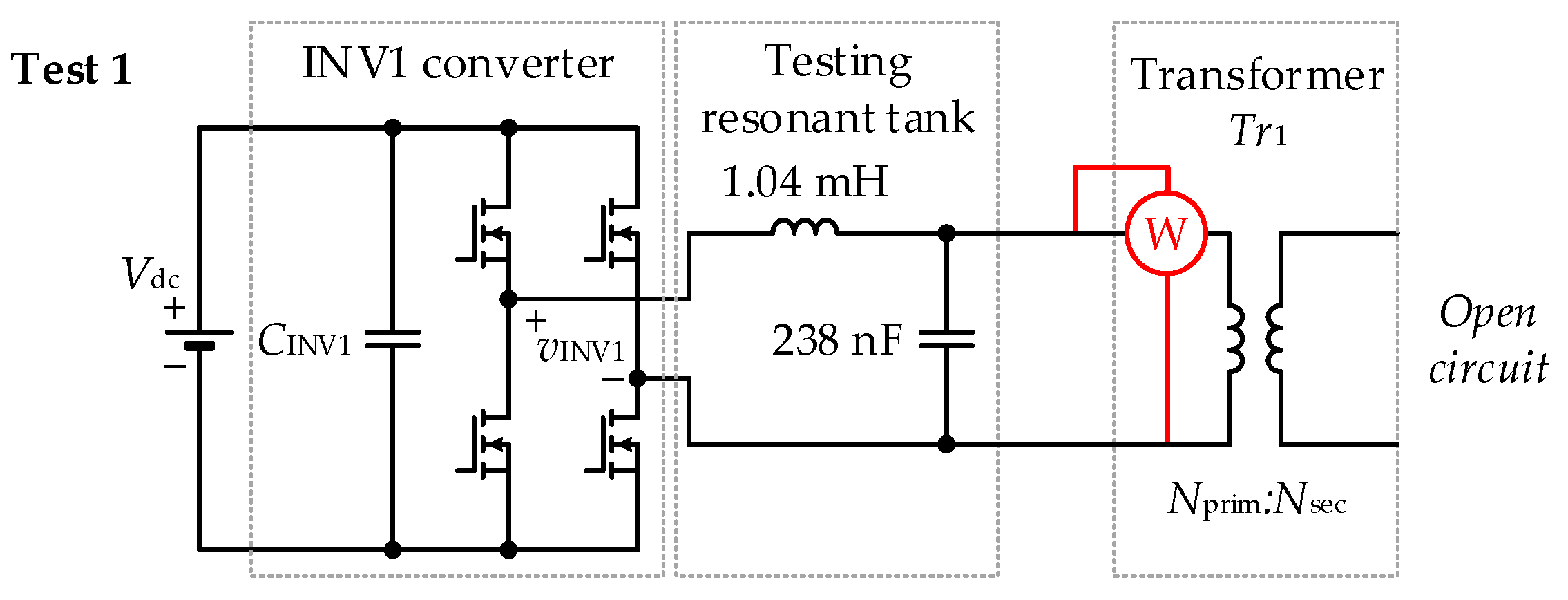

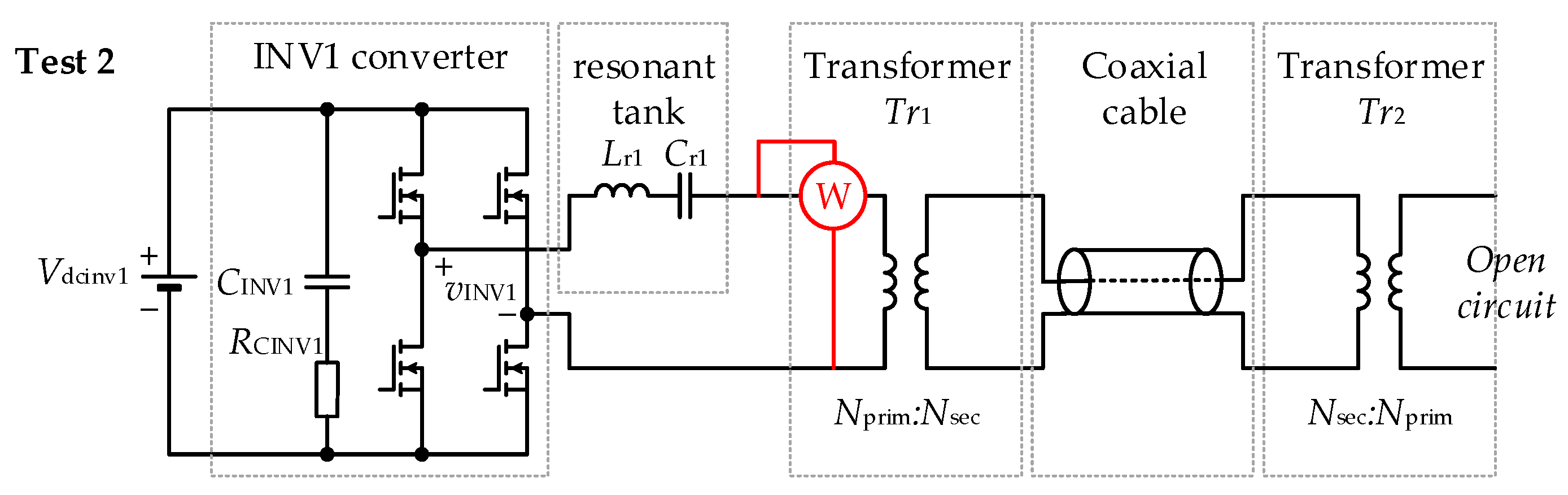

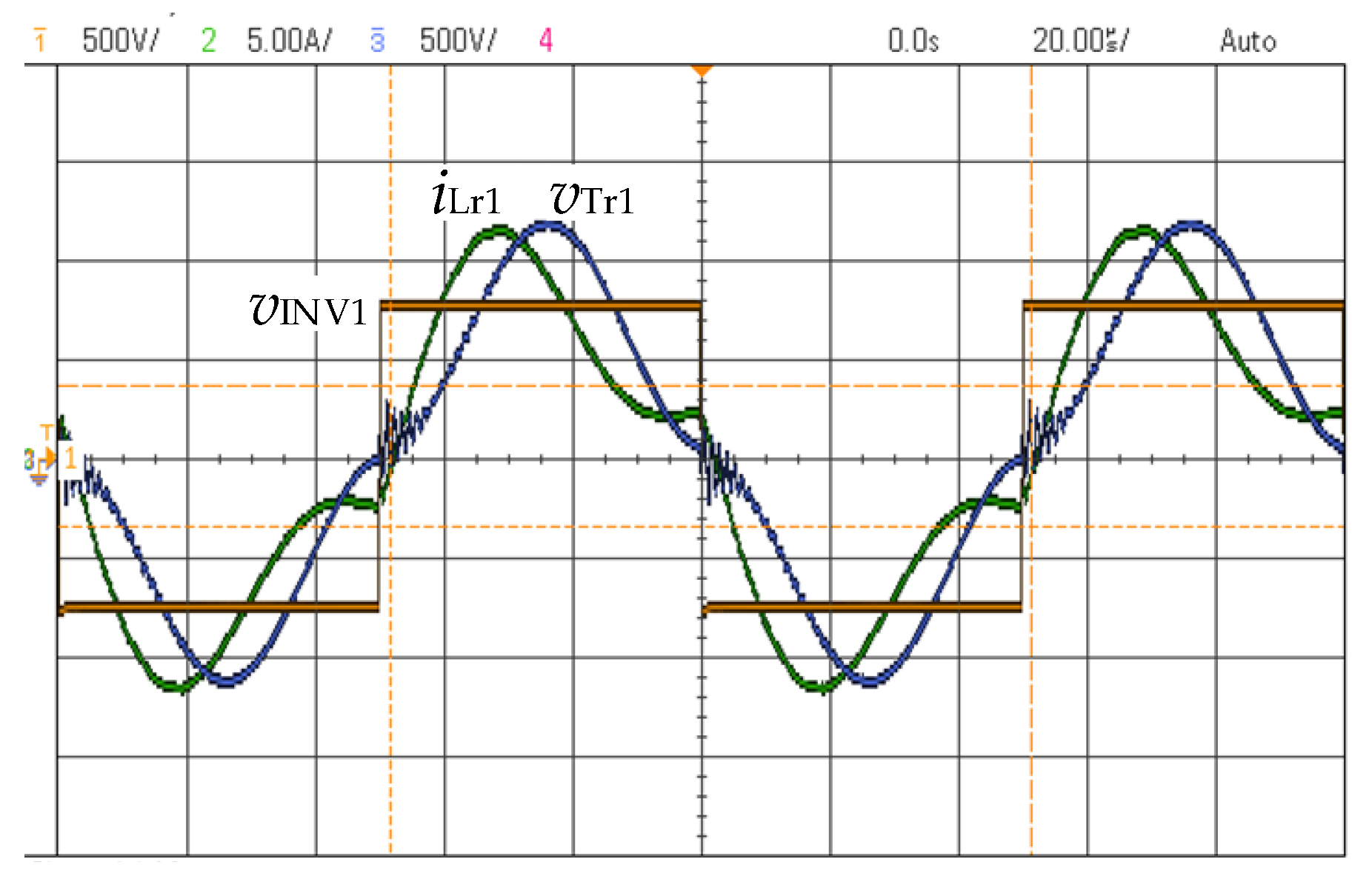

- INV1 is a converter that operates as a resonant inverter to deliver the energy to High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable (HVHFCC) through a resonant tank and the Tr1 transformer. The switching frequency is set to 10 kHz, and the HVHFCC operating voltage is 3.5 kV. The transformer Tr1 is a step-up transformer with the turns ratio Nprim/Nsec = 0.2288.

- A 100 m coaxial cable RG11/U was used as the HVHFCC. The RG11/U cable meets the US Military specification MIL-C-17, with a nominal peak voltage of 5.2 kV and a characteristic impedance of Z = 75 Ω.

- Transformer TR2 with the second resonant tank and REC2 rectifier converts energy from the coaxial cable to a DC output, at which the voltage is varied between 700 V and 870 V. The combination of converters INV1 and REC2, two transformers Tr1 and Tr2, a coaxial cable, and two resonant circuits forms a converter known as the dual-series resonant converter. The transformer TR2 is a step-down transformer with the turns ratio Nsec/Nprim = 4.3703.

- INV2 is a three-phase inverter. Converter INV2 is structurally identical to REC1; however, the direction of power transfer is opposite. In REC1, power flows from the AC side to the DC side, while in INV2, it flows from the DC side to the AC side. The inverter produces a three-phase 500 V, 50 Hz supply. An LCL filter with the same topology as that used in REC1 is connected to the INV2 output. INV2 is controlled using PWM with a switching frequency of 50 kHz, and third-harmonic injection is applied to the modulation signals to increase the available modulation range.

- INV3 is a resonant inverter, which operates as a high-frequency, high-voltage AC source to deliver the energy to the REC4 converter through the TR3 transformer, a capacitive coupler, and TR4. The switching frequency of INV3 is equal to 300 kHz.

- Transformer TR4 with the REC4 is mounted on the moving part of the suspended monorail and converts energy from the capacitive coupler to a 48 V DC voltage. This voltage feeds the battery charger.

3. Power Loss Analysis

3.1. AC Grid Converter Losses

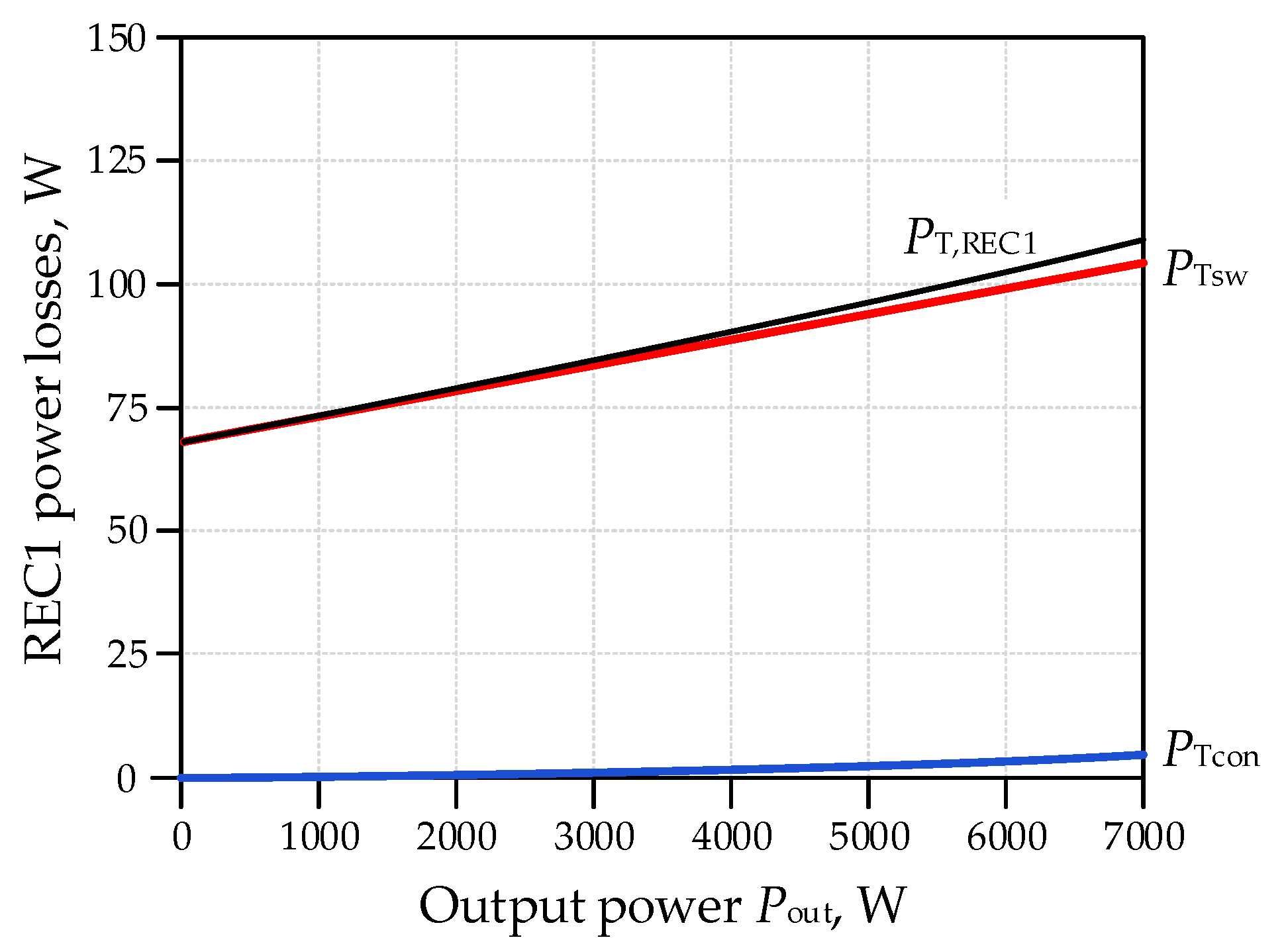

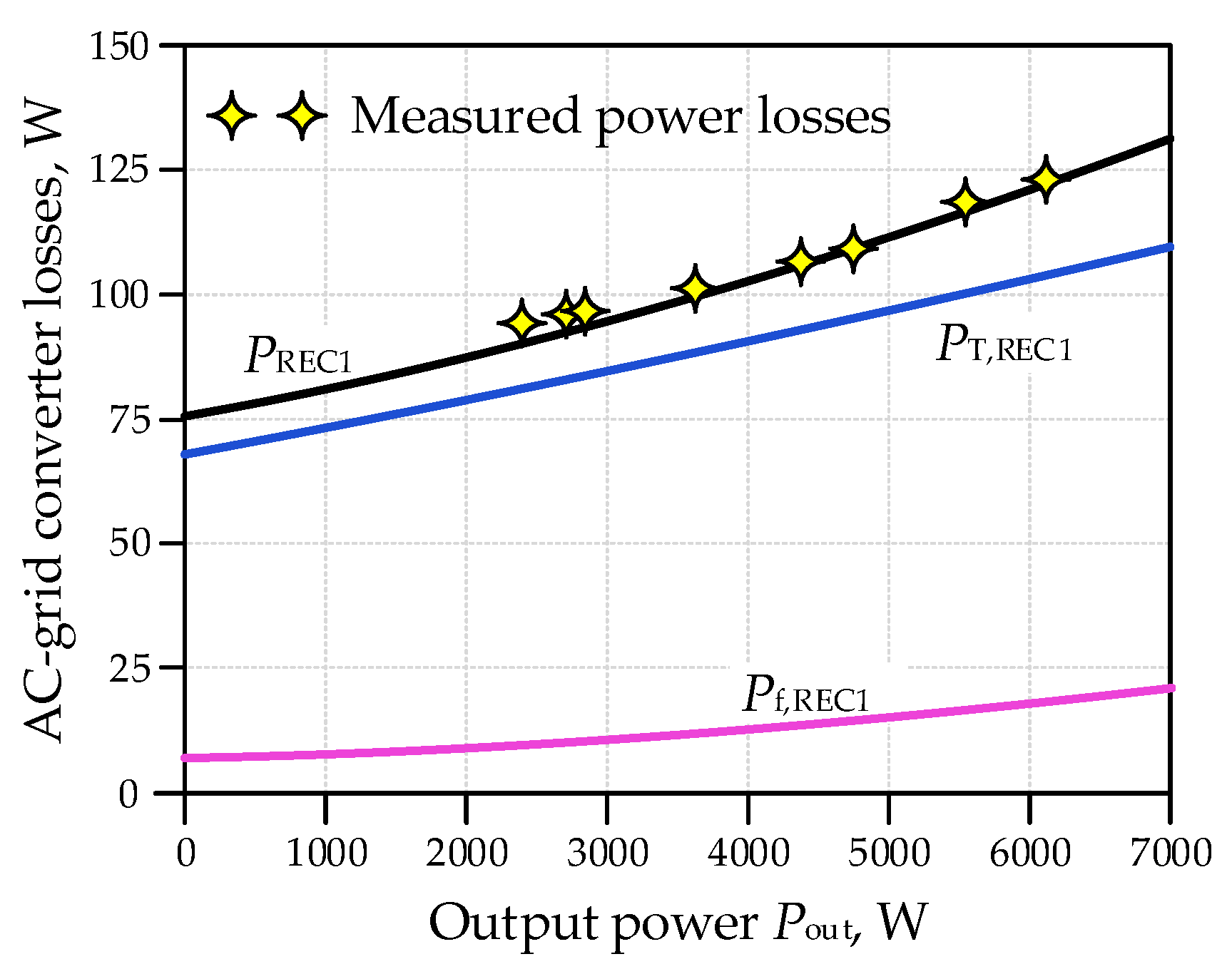

3.1.1. REC1 Converter Losses

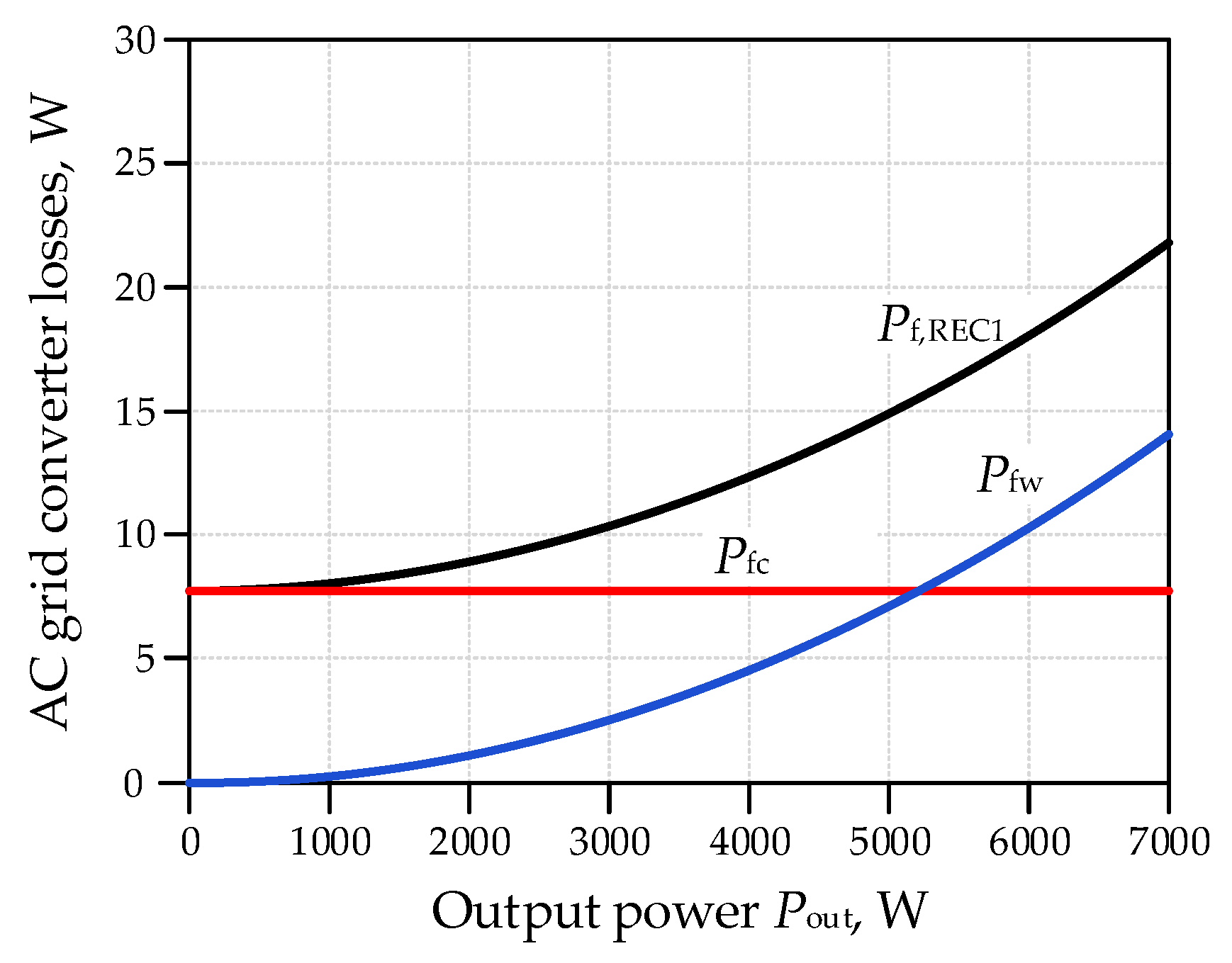

3.1.2. Power Losses Generated in Passive Filters of the AC Grid Converter

3.1.3. Power Losses Generated in the AC Grid Converter

3.2. Dual Resonant Converter Losses

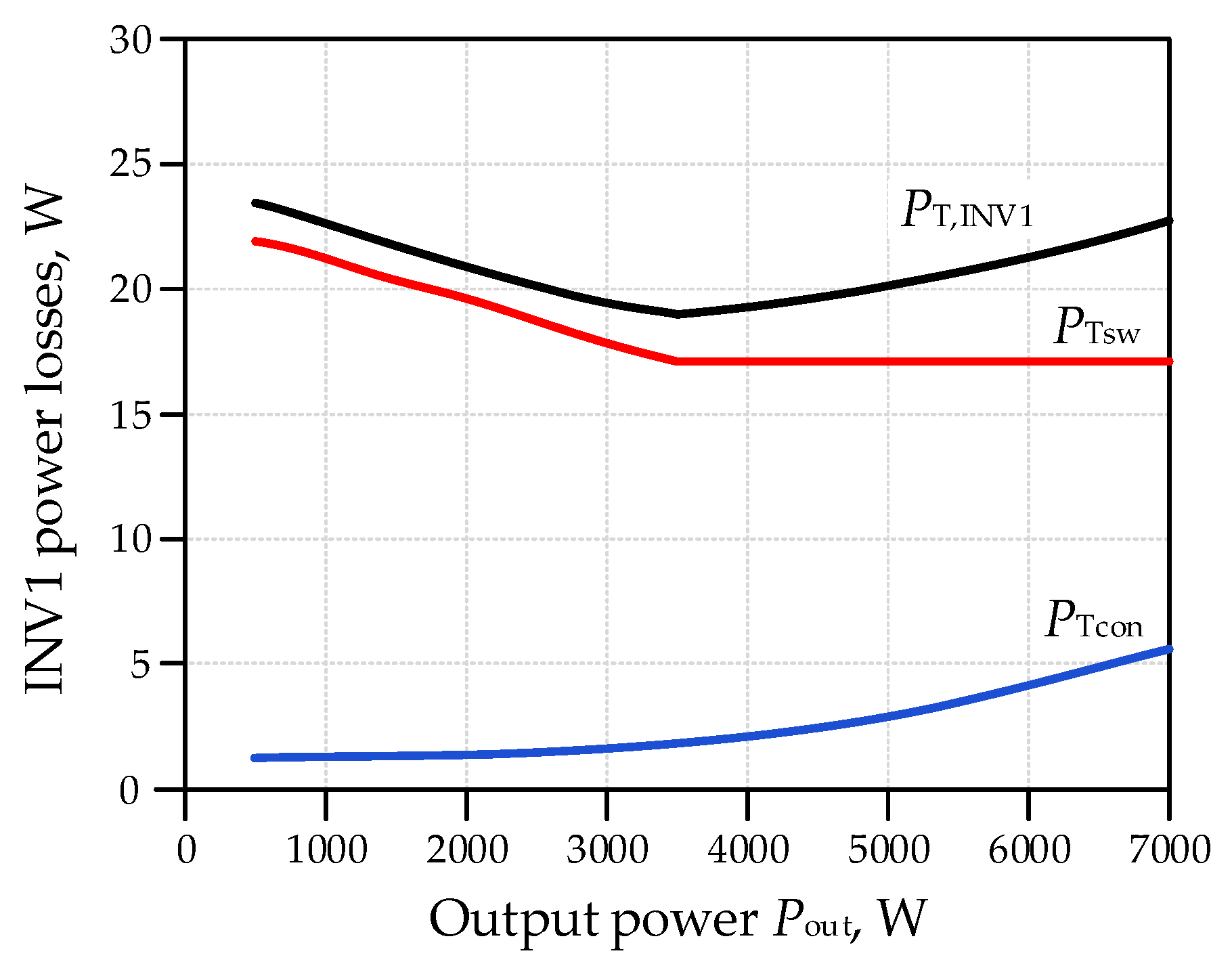

- Conduction and switching losses in INV1 converter transistors, PINV1Tcon, PINV1Tsw.

- Winding losses in Lr1 and Lr2 inductors, PLr1w, PLr2w.

- Core losses in Lr1 and Lr2 inductors, PLr1c and PLr2c.

- Primary winding losses in Tr1 and Tr2 transformers, PTr1wp, PTr2wp.

- Core losses in Tr1 and Tr2 transformers, PTr1c, PTr2c.

- Secondary winding losses in Tr1 and Tr2 transformers, PTr1ws, PTr2ws.

- Wire and dielectric losses in the coaxial cable, Pcoaxw, Pcoaxd.

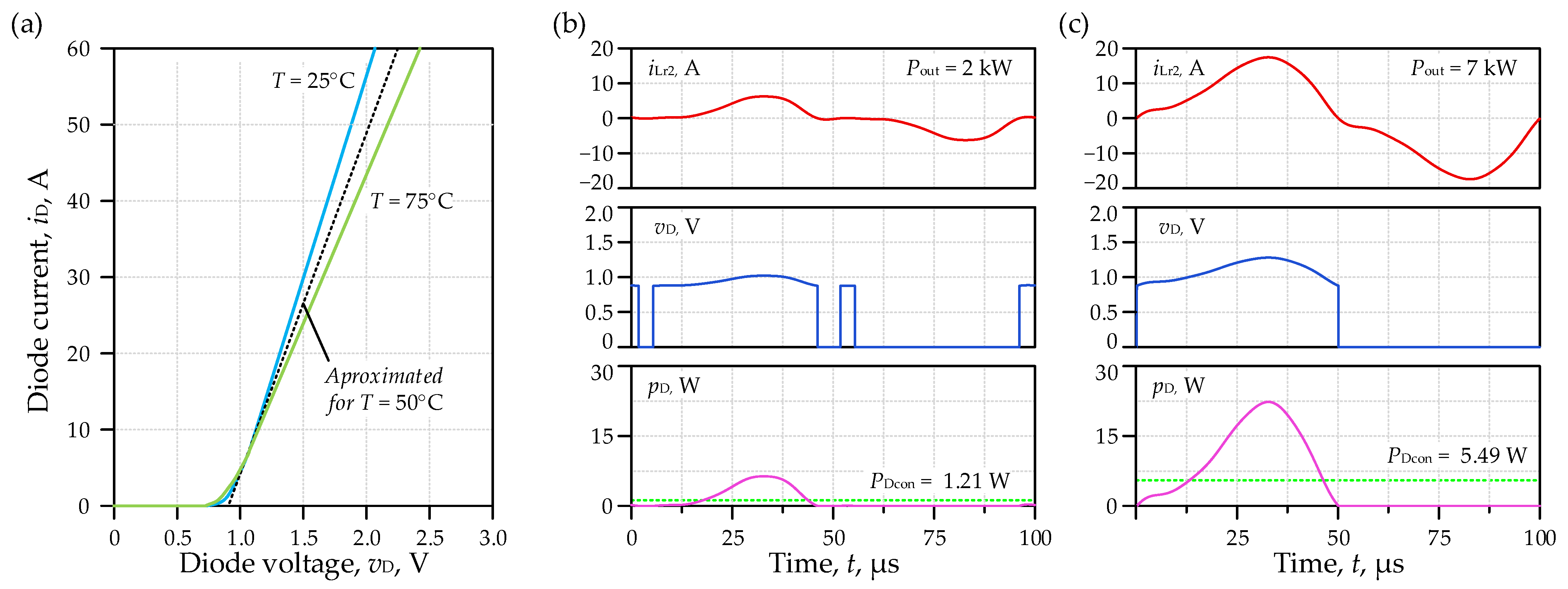

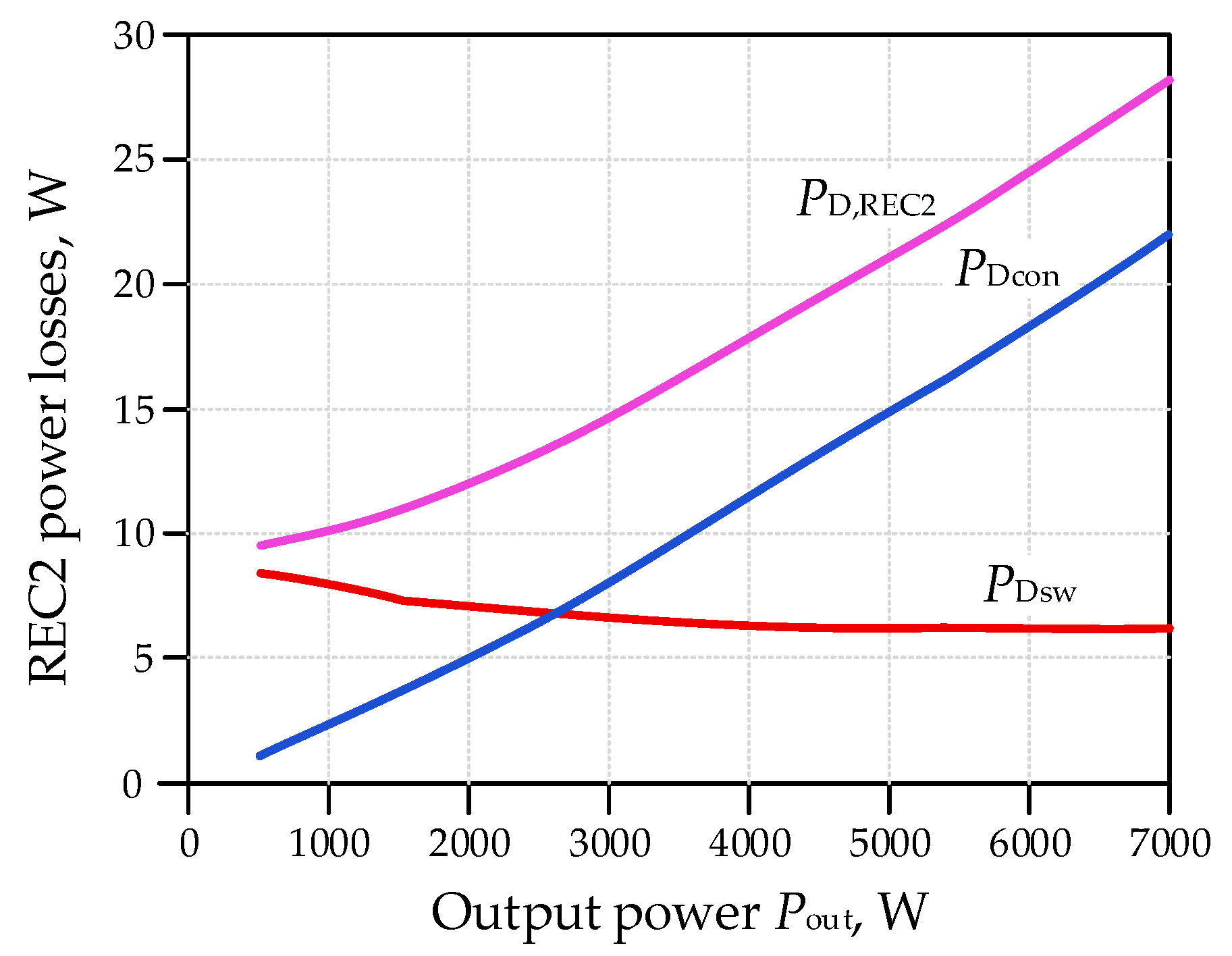

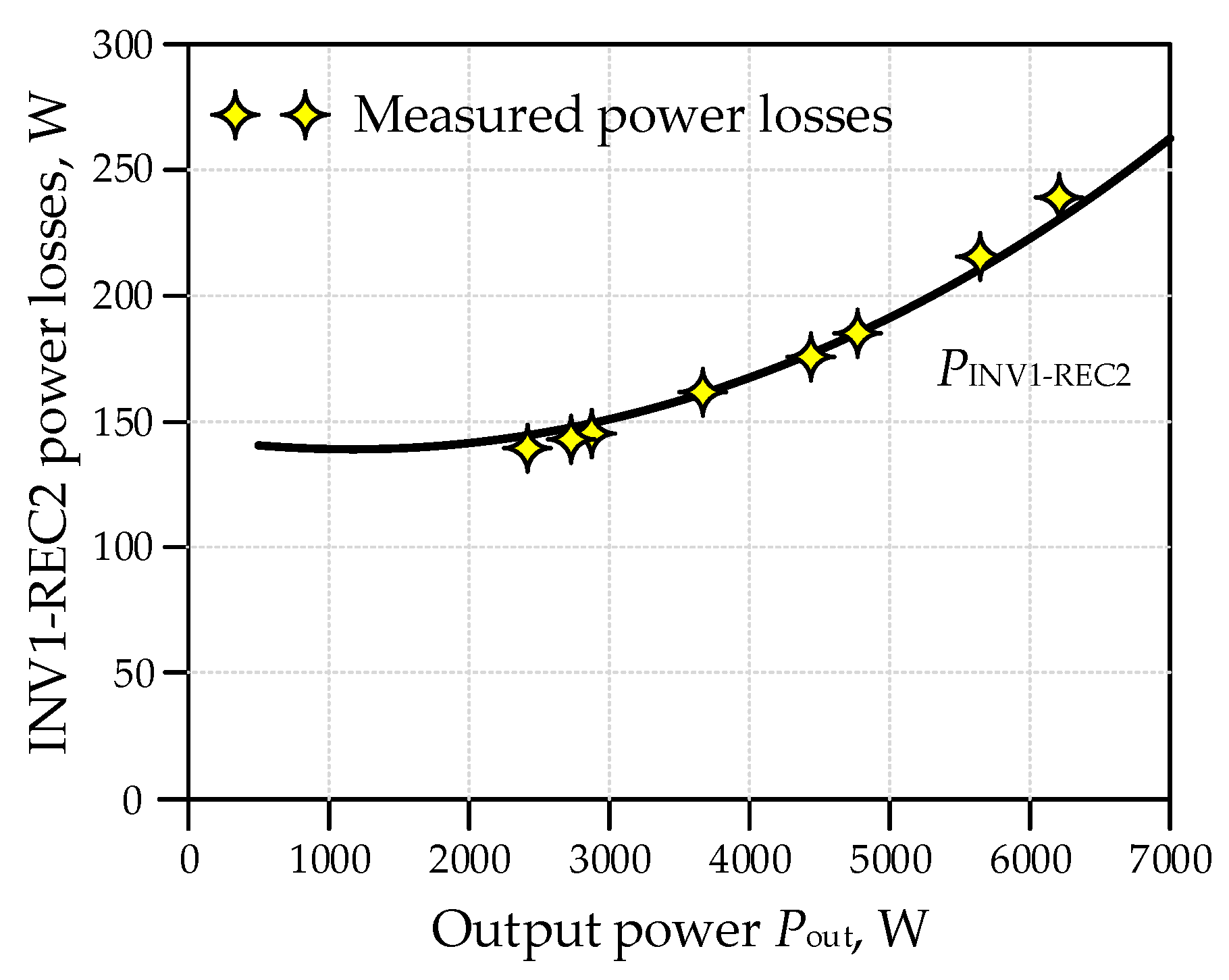

- Conduction and switching losses in REC2 converter diodes, PREC2Dcon, PREC2Dsw.

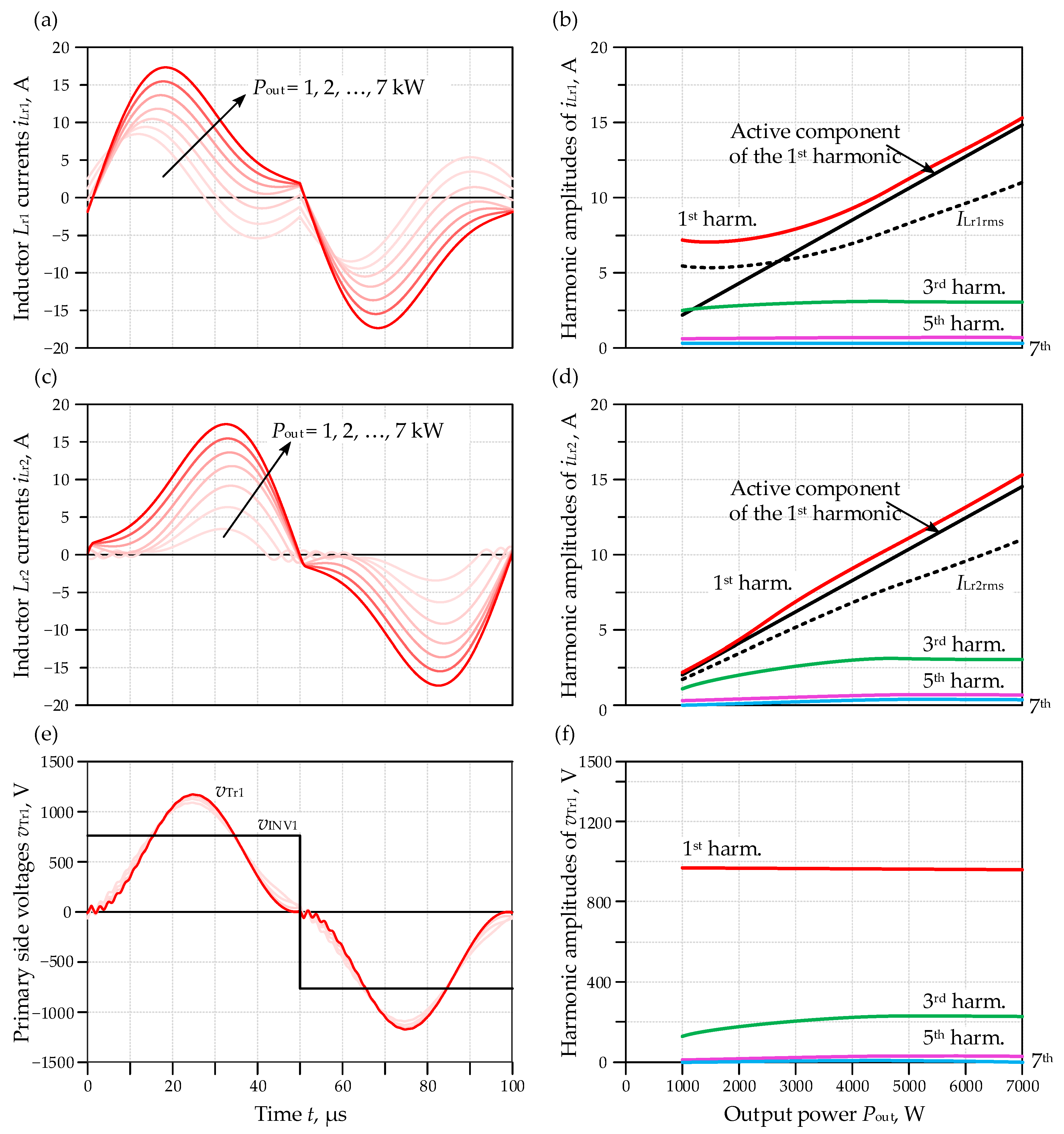

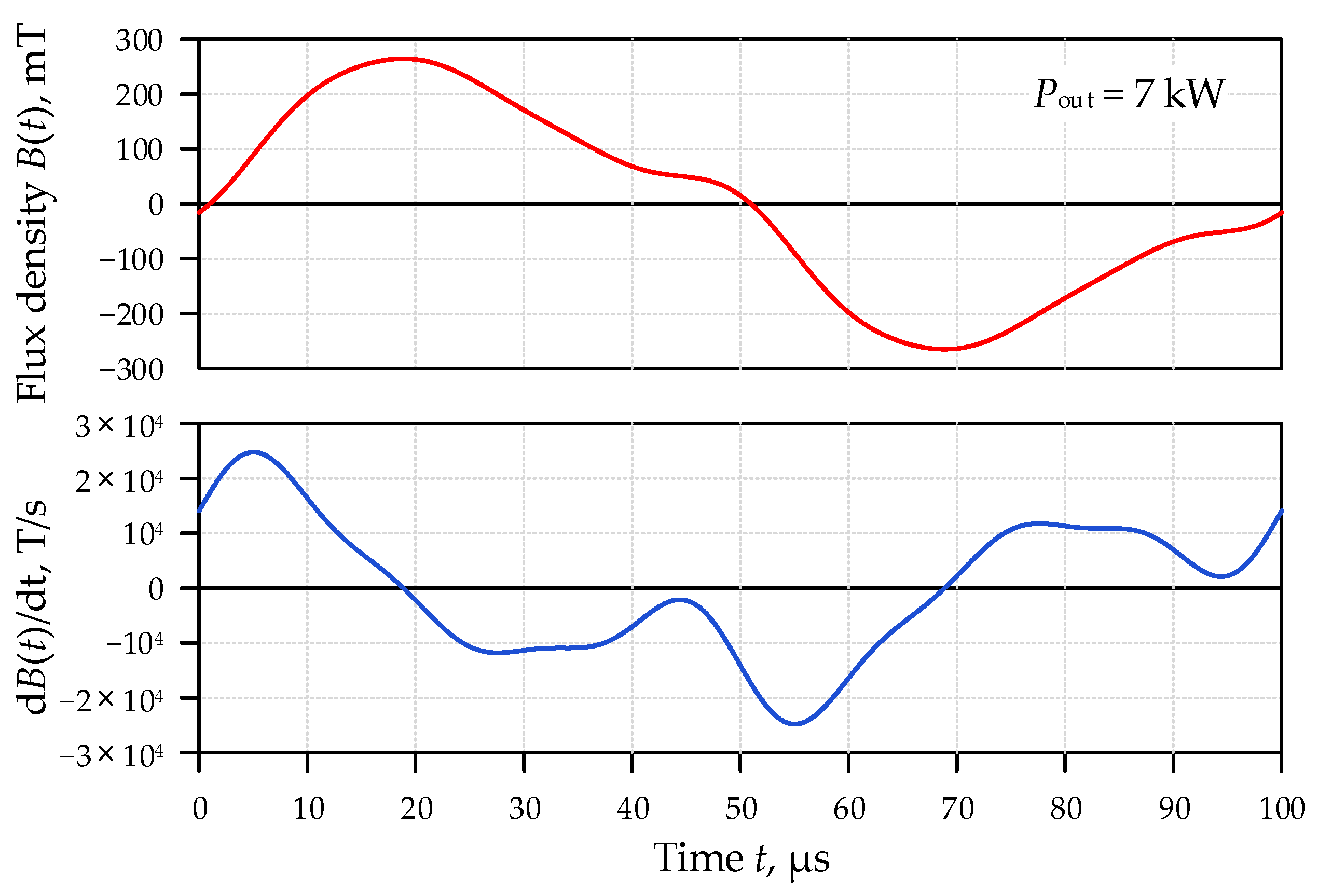

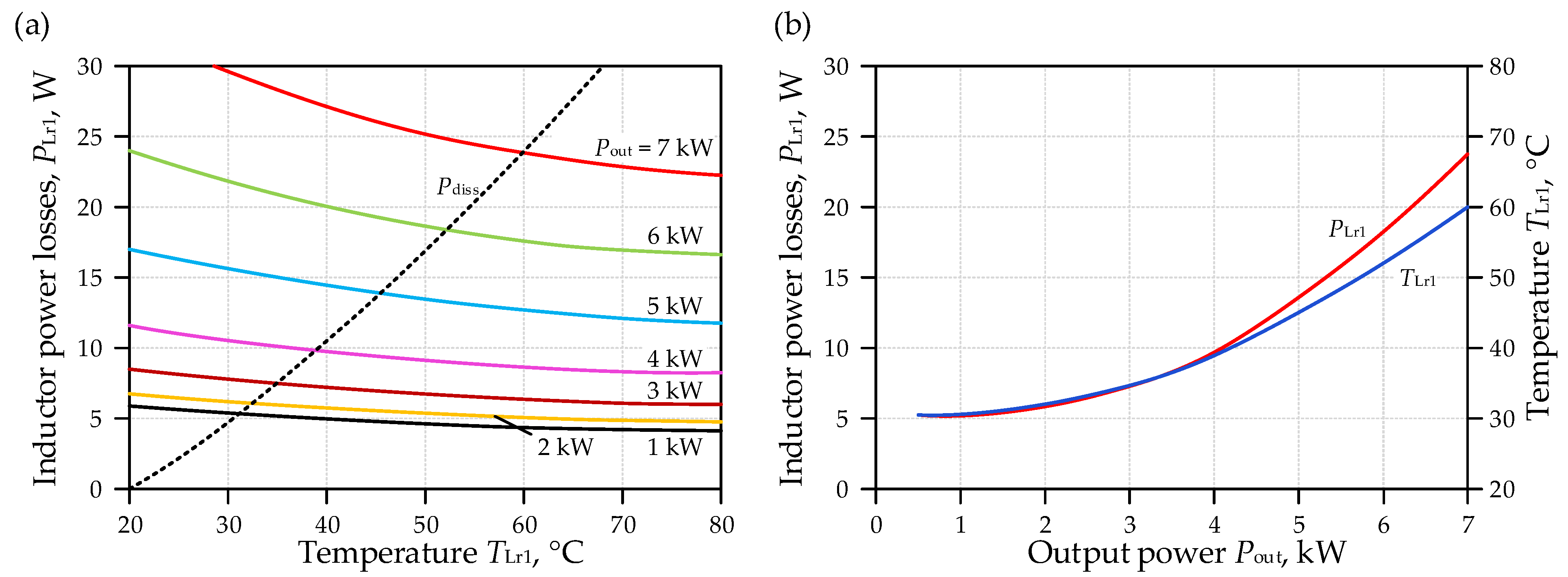

3.2.1. Power Losses in Resonant Inductor Lr1

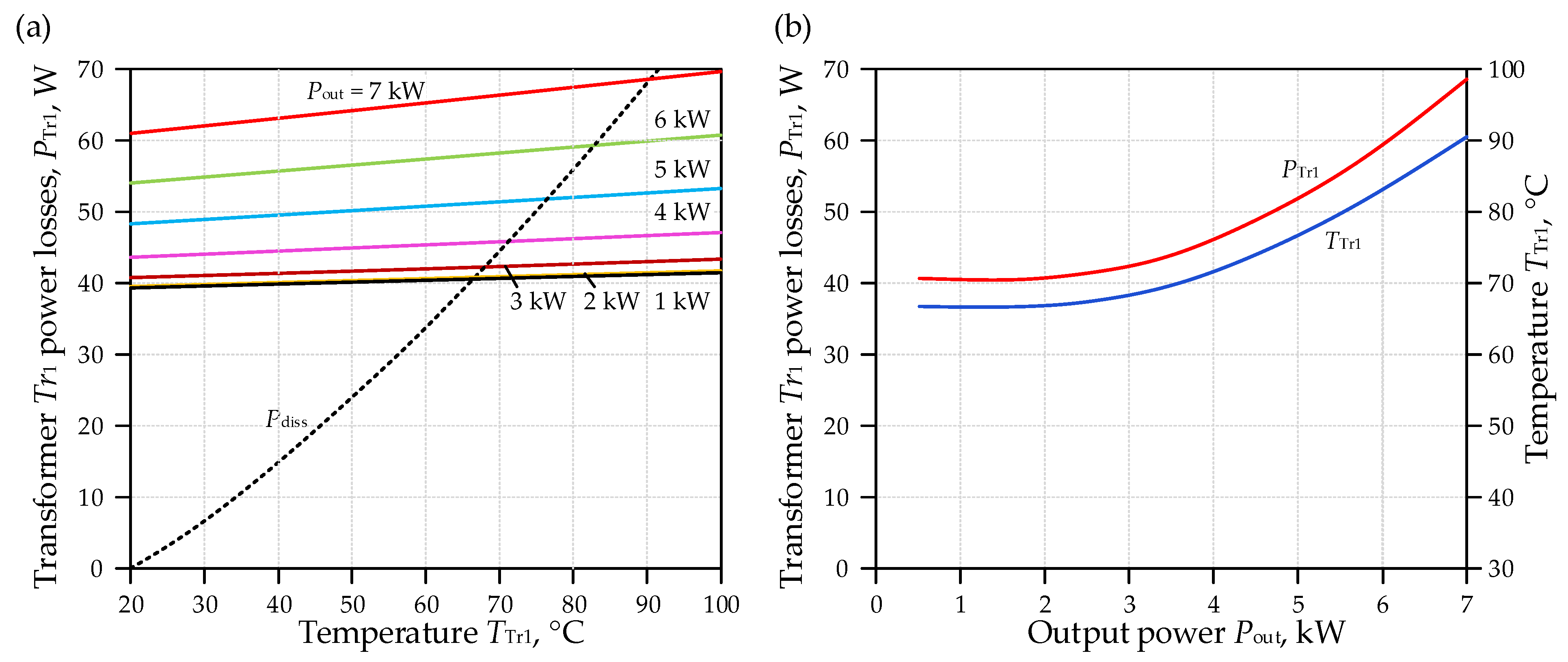

3.2.2. Power Losses in Transformer Tr1

3.2.3. Power Losses in Coaxial Cable

3.2.4. Power Losses in Converter INV1

3.2.5. Power Losses in Converter REC2

3.2.6. Power Losses in Dual Resonant Converter Tracks and Wires

3.2.7. Power Losses Generated in the Dual Resonant Converter

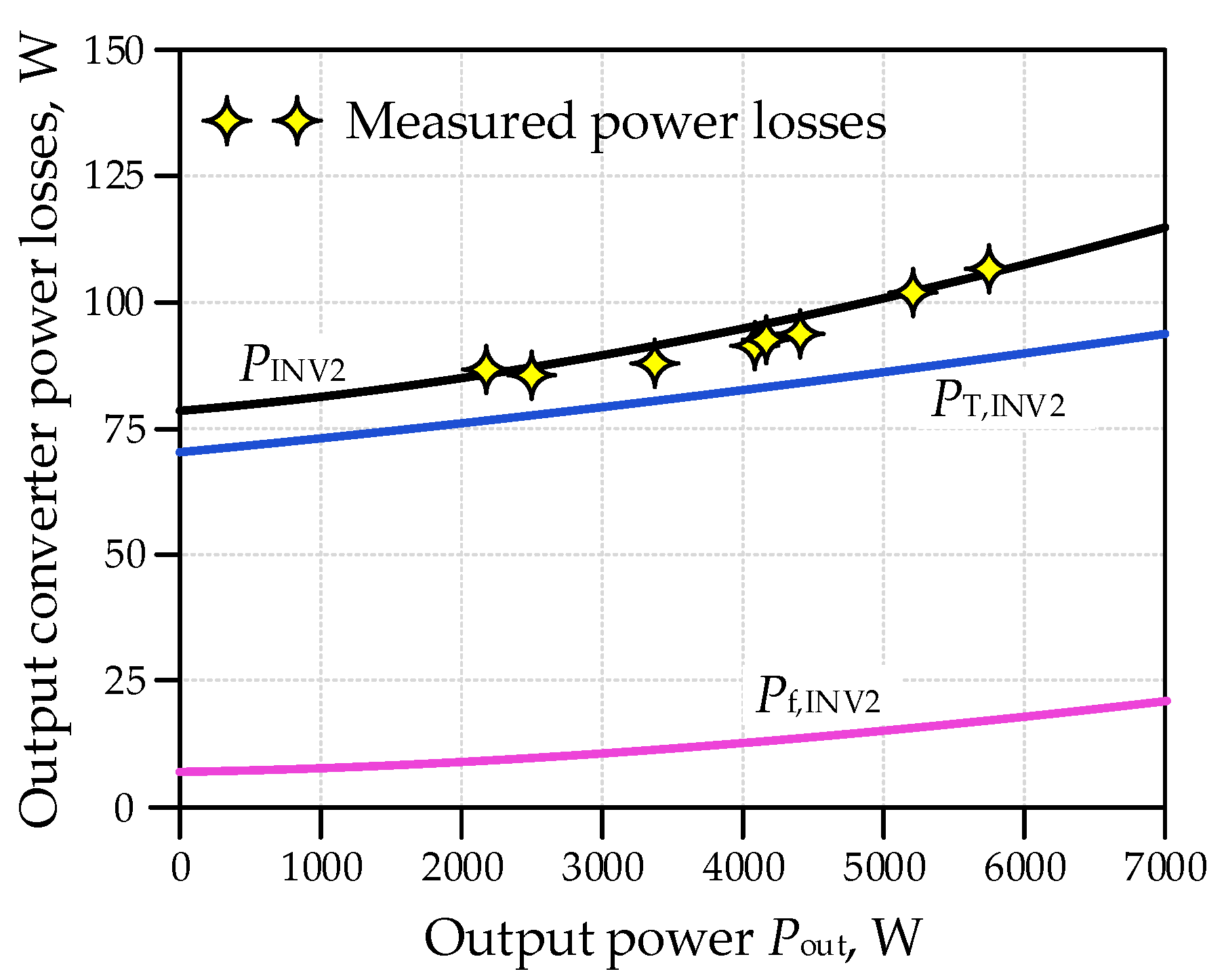

3.3. Output Converter Losses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abramushkina, E.; Zhaksylyk, A.; Geury, T.; El Baghdadi, M.; Hegazy, O. A Thorough Review of Cooling Concepts and Thermal Management Techniques for Automotive WBG Inverters: Topology, Technology and Integration Level. Energies 2021, 14, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, A.; Vinnikov, D.; Lehtla, T. Cooling Methods for High-Power Electronic Systems. Sci. J. Riga Tech. Univ. 2011, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, M.G.; Mirzaeva, G.; Mitchell, S.D.; Gay, D. DC power vs AC power for mobile mining equipment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Industry Application Society Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–9 October 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursiainen, J.; Rekola, J.; Juntunen, R.; Valtee, M.; Peltoniemi, P. DC microgrid concept for mine environment. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’20 ECCE Europe), Lyon, France, 7–11 September 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlązak, N.; Korzec, M.; Cheng, J. Using Battery-Powered Suspended Monorails in Underground Hard Coal Mines to Improve Working Conditions in the Roadway. Energies 2022, 15, 7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuslap, E.; Li, J.; Talehatibieke, A.; Hitch, M. Battery Electric Vehicles in Underground Mining: Benefits, Challenges, and Safety Considerations. Energies 2025, 18, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.A.; Kouro, S.; Perez, M.A.; Echeverria, J. DC–DC MMC for HVdc Grid Interface of Utility-Scale Photovoltaic Conversion Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.M.; Franquelo, L.G.; Bialasiewicz, J.T.; Galvan, E.; Portillo-Guisado, R.C.; Prats, M.A.M.; Leon, J.I.; Moreno-Alfonso, N. Power-Electronic Systems for the Grid Integration of Renewable Energy Sources: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2006, 53, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawder, M.T.; Suthar, B.; Northrop, P.W.C.; De, S.; Hoff, C.M.; Leitermann, O.; Crow, M.L.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Subramanian, V.R. Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) and Battery Management System (BMS) for Grid-Scale Applications. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudalov, A.; Chartouni, D.; Ohler, C. Optimizing a Battery Energy Storage System for Primary Frequency Control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 22, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaramasu, V.; Wu, B.; Sen, P.C.; Kouro, S.; Narimani, M. High-Power Wind Energy Conversion Systems: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 740–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathabadi, H. Novel Maximum Electrical and Mechanical Power Tracking Controllers for Wind Energy Conversion Systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2017, 5, 1739–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, J.; Shi, D.; Wang, Z. Design and Performance Evaluation of the Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC)-based Grid-tied PV-Battery Conversion System. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Portland, OR, USA, 23–27 September 2018; pp. 2649–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, J. MMC-Based PV Grid-Connected System with SMES-Battery Hybrid Energy Storage. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Applied Superconductivity and Electromagnetic Devices (ASEMD), Tianjin, China, 27 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, H.; Yazdani, A. A Hybrid MMC-Based Photovoltaic and Battery Energy Storage System. IEEE Power Energy Technol. Syst. J. 2019, 6, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skóra, M.; Rogala-Rojek, J.; Jendrysik, S.; Stankiewicz, K.; Polnik, B.; Kaczmarczyk, Z.; Kasprzak, M.; Lasek, P.; Przybyła, K. Innovative Capacitive Wireless Power System for Machines and Devices. Energies 2025, 18, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, M.; Kaczmarczyk, Z.; Frania, K.; Kierepka, K.; Przybyla, K.; Zimoch, P. High Voltage High Frequency Single Wire Energy Transfer. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 20th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC), Brasov, Romania, 25 September 2022; pp. 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, X.; Jia, J.; Zhao, H.; Li, X. Shield Reliability Analysis-Based Transfer Impedance Optimization Model for Double Shielded Cable of Electric Vehicle. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5373094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolshev, V.; Yuferev, L.; Vinogradov, A.; Bukreev, A. Single-Wire Transmission Methods: Justification of a Single-Wire Resonant Power Transmission System. Energies 2023, 16, 5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chen, X.; Qi, C.; Mu, X. Modeling and Construction of Single-Wire Power Transmission Based on Multilayer Tesla Coil. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 6682–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczuk, M.K.; Czarkowski, D. Resonant Power Converters, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reznik, A.; Simoes, M.G.; Al-Durra, A.; Muyeen, S.M. LCL Filter Design and Performance Analysis for Grid-Interconnected Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 50, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H. Optimal Design of LCL Filter in Grid–connected Inverters. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmanowski, M.; Jarek, G.; Michalak, J.; Jelen, M. Design of the AC Filter for Two-Level Converter Operating in IT Grids. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 20th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC), Brasov, Romania, 25 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Infineon Technologies AG. FF23MR12W1M1P_B11 EasyDUAL Module with CoolSiC™ Trench MOSFET and PressFIT Datasheet. Available online: https://www.infineon.com/part/FF23MR12W1M1P-B11 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Venkatachalam, K.; Sullivan, C.R.; Abdallah, T.; Tacca, H. Accurate Prediction of Ferrite Core Loss with Nonsinusoidal Waveforms Using Only Steinmetz Parameters. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE Workshop on Computers in Power Electronics, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, 3–4 June 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, J.; Brockmeyer, A.; De Doncker, R.W. Calculation of Losses in Ferro- and Ferrimagnetic Materials Based on the Modified Steinmetz Equation. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the 1999 IEEE Industry Applications Conference. Thirty-Fourth IAS Annual Meeting (Cat. No.99CH36370), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 3–7 October 1999; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 2087–2092. [Google Scholar]

- Undeland, M.; Robbins, W. Power Electronics: Converter Applications and Design, 3rd ed.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stancu, C.; Notingher, P.V.; Panaitescu, D.; Marinescu, V. Dielectric Losses in Polyethylene/Neodymium Composites. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM), Bran, Romania, 22–24 May 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Konecna, Z. Temperature Dependence of Electrical Parameters of Coaxial Cables. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Diagnostics in Electrical Engineering (Diagnostika), Pilsen, Czech Republic, 6–8 September 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki, M.; Tokoro, T.; Nakamori, M.; Nagao, M. High Field Dielectric Dissipation Factor of Polyethylene. In Proceedings of the 1984 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Insulation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–13 June 1984; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Florkowski, M.; Kuniewski, M.; Mikrut, P. Effect of Voltage Harmonics on Dielectric Losses and Dissipation Factor Interpretation in High-Voltage Insulating Materials. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 226, 109973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide, A.M.; Leon, J.I.; Rojas, C.A.; Berger, J.G.; Stowhas-Villa, A.; Wilson-Veas, A.H.; Buticchi, G.; Kouro, S. The Role of Modulation Techniques on Power Device Thermal Performance in Two-Level VSI Converters. Electronics 2025, 14, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datasheet of Zero Recovery Silicon Carbide Schottky Diode MSC030SDA170B. Available online: https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/aemDocuments/documents/PSDS/ProductDocuments/DataSheets/Microsemi_MSC030SDA170B_SiC_Schottky_Diode_Datasheet_A.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Galigekere, V.P.; Kazimierczuk, M.K. Performance of SiC Schottky Diodes. In Proceedings of the 2007 50th Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5 August 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 682–685. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M.; Giziewski, S.; Pietryka, J.; Krzeminski, Z. Performance Comparison of SiC Schottky Diodes and Silicon Ultra Fast Recovery Diodes. In Proceedings of the 2011 7th International Conference-Workshop Compatibility and Power Electronics (CPE), Tallinn, Estonia, 1–3 June 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| AC grid voltage, phase-to-phase rms value | Vg | 500 V |

| REC1 converter DC voltage | Vdc | 760 V |

| Common-mode choke inductance | Lcm | 29 mH |

| Common-mode filter capacitance | Ccm | 100 nF |

| Common-mode choke winding resistance | RLcmw | 10 mΩ |

| LCL filter inductance Lf1 | Lf1 | 500 μH |

| LCL filter inductance Lf2 | Lf2 | 65 μH |

| LCL filter capacitance Cf | Cf | 1 μF |

| Winding resistance of inductor Lf1 | RLf1w | 35 mΩ |

| Winding resistance of inductor Lf2 | RLf2w | 16 mΩ |

| Series resistance in the capacitor path RCf | RCf | 1 Ω |

| The series equivalent resistance of the DC-link capacitors | RCREC1 | 26 mΩ |

| DC-link capacitances | CINV1, CREC2 | 705 μF |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| INV1 converter DC voltage | Vdcin1 | 760 V |

| Resonant tank inductance | Lr1, Lr2 | 1.04 mH |

| Resonant tank capacitance | Cr1, Cr2 | 238 nF |

| Winding resistance of inductor Lr1 @20 °C | RLr1w, RLr2w | 25.5 mΩ |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 primary side voltage | Vprim | 800 V |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 secondary side voltage | Vsec | 3500 V |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 numbers of turns | Nprim/Nsec | 27/118 |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 primary side winding resistance @20 °C | RTr1wp, RTr2wp | 100 mΩ |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 secondary side winding resistance @20 °C | RTr1ws, RTr2ws | 1.2 Ω |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 magnetizing inductance | LTr1m, LTr2m | 35 mH |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 primary side leakage inductance | LTr1σp, LTr2σp | 26 μH |

| Transformer Tr1, Tr2 secondary side leakage inductance | LTr1σs, LTr2σs | 497 μH |

| Coaxial cable length | lcoax | 100 m |

| Coaxial cable wire resistance | Rcoaxw | 2.3 Ω |

| Coaxial cable capacitance | Ccoax | 6.7 nF |

| Input and output capacitances | CINV1, CREC2 | 705 μF |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Inductance | Lr1 | 1.04 mH |

| Type of the core | --- | E65 |

| Number of stacked cores | Nc | 6 |

| Number of turns | N | 21 |

| Cross-sectional area of magnetic cores | Ac | 32.4 cm2 |

| Core material | --- | 3C94 |

| Core size (all cores) | wm × h × l | 65 mm × 65.6 mm × 164.4 mm |

| Core volume (all cores) | Vc | 474 cm3 |

| Winding resistance @20 °C | RLr1w | 25.5 mΩ |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetizing inductance | LTr1m | 35 mH |

| Number of turns | Nprim/Nsec | 27/118 |

| Core size (all cores) | wm × h × l | 80 mm × 76.2 mm × 198 mm |

| Primary winding resistance @20 °C | RTr1wp | 144 mΩ |

| Secondary winding resistance @20 °C | RTr1ws | 1.74 Ω |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Type of coaxial cable | --- | RG11/U |

| Cable length | lcoax | 100 m |

| Characteristic impedance | Z | 75 Ω |

| Cable capacitance | Ccoax | 6.7 nF |

| Cable resistance | Rcoax | 2.26 Ω |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zygmanowski, M.; Bodora, A.; Domoracki, A.; Frania, K.; Hetmańczyk, J.; Jarek, G.; Jeleń, M.; Kaczmarczyk, Z.; Kasprzak, M.; Lasek, P.; et al. Power Losses of the High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable Energy Transfer System. Electronics 2026, 15, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010093

Zygmanowski M, Bodora A, Domoracki A, Frania K, Hetmańczyk J, Jarek G, Jeleń M, Kaczmarczyk Z, Kasprzak M, Lasek P, et al. Power Losses of the High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable Energy Transfer System. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleZygmanowski, Marcin, Aleksander Bodora, Arkadiusz Domoracki, Krystian Frania, Janusz Hetmańczyk, Grzegorz Jarek, Michał Jeleń, Zbigniew Kaczmarczyk, Marcin Kasprzak, Paweł Lasek, and et al. 2026. "Power Losses of the High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable Energy Transfer System" Electronics 15, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010093

APA StyleZygmanowski, M., Bodora, A., Domoracki, A., Frania, K., Hetmańczyk, J., Jarek, G., Jeleń, M., Kaczmarczyk, Z., Kasprzak, M., Lasek, P., Legutko, P., Michalak, J., Polnik, B., Przybyła, K., Skóra, M., & Stankiewicz, K. (2026). Power Losses of the High-Voltage High-Frequency Coaxial Cable Energy Transfer System. Electronics, 15(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010093