MetaD-DT: A Reference Architecture Enabling Digital Twin Development for Complex Engineering Equipment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Technical Requirements for Engineering Equipment Digital Twins

2.1. Core Challenges and Architectural Implications

- 1.

- Modeling Complexity

- 2.

- Harsh Operating Conditions

- 3.

- System Reliability

- 4.

- Intelligent Adaptability

- 5.

- Differentiated Customization

2.2. Foundational Architectural Requirements

- Digital Modeling with Mechanism–Data Fusion

- 2.

- Real-time Computing and Data Synchronization

- 3.

- Data Assimilation and Digital Twin Evolution

- 4.

- Predictive Maintenance and Intelligent Decision-making

- 5.

- Multi-dimensional Human–Computer Interaction

3. The MetaD-DT Architecture and Core Functions

3.1. MetaD-DT Architectural Hierarchy

- 1.

- Resource layer

- 2.

- Development layer

- 3.

- Function layer

- 4.

- Application layer

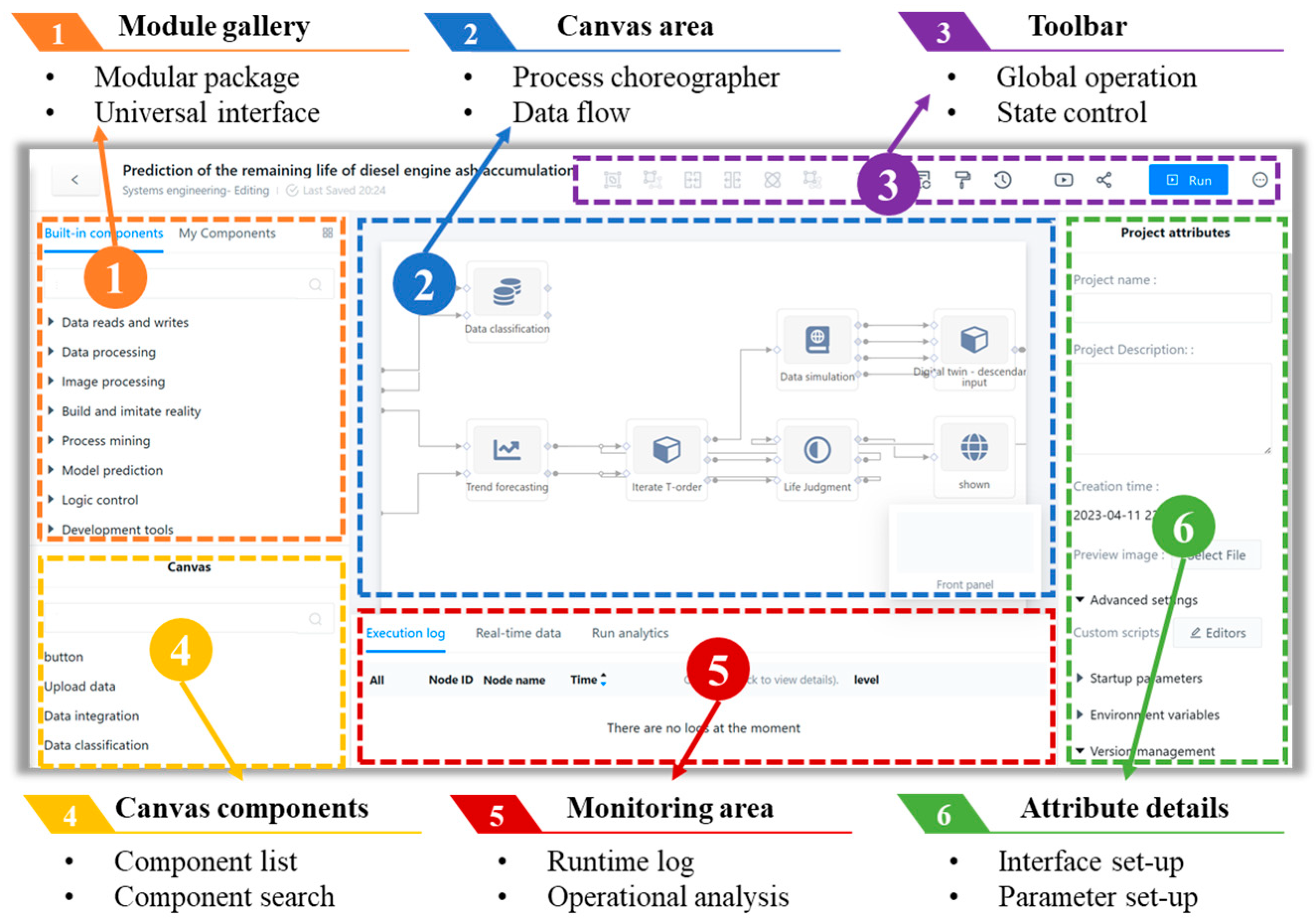

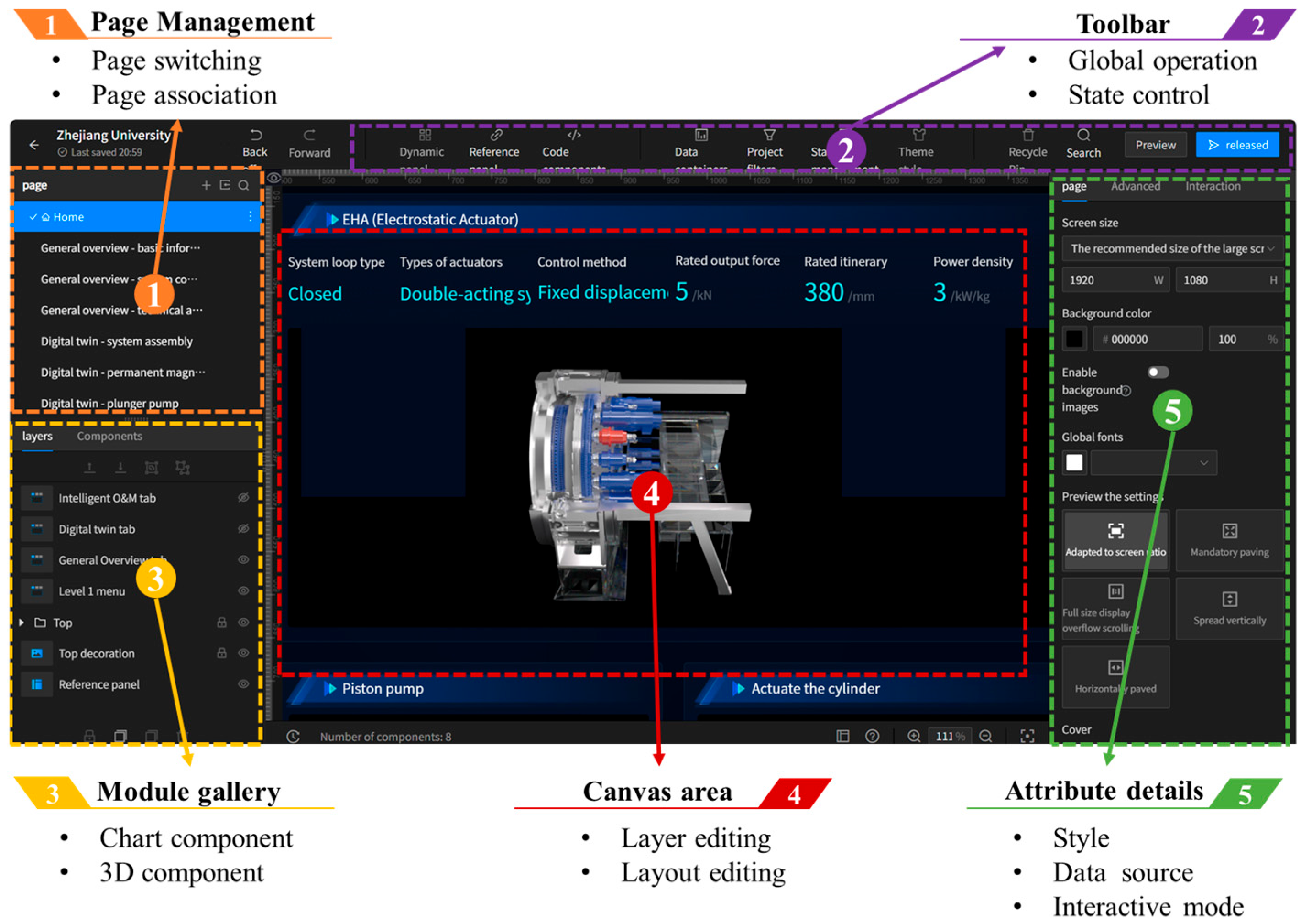

3.2. Core Functional Modules of the Function Layer

- Basic Library

- 2.

- Model Module

- 3.

- Algorithm Module

- 4.

- Data Module

- 5.

- Computing Engine

- 6.

- Communication Module

- 7.

- Interaction Module

- 8.

- Visualization Module

- 9.

- Deployment Module

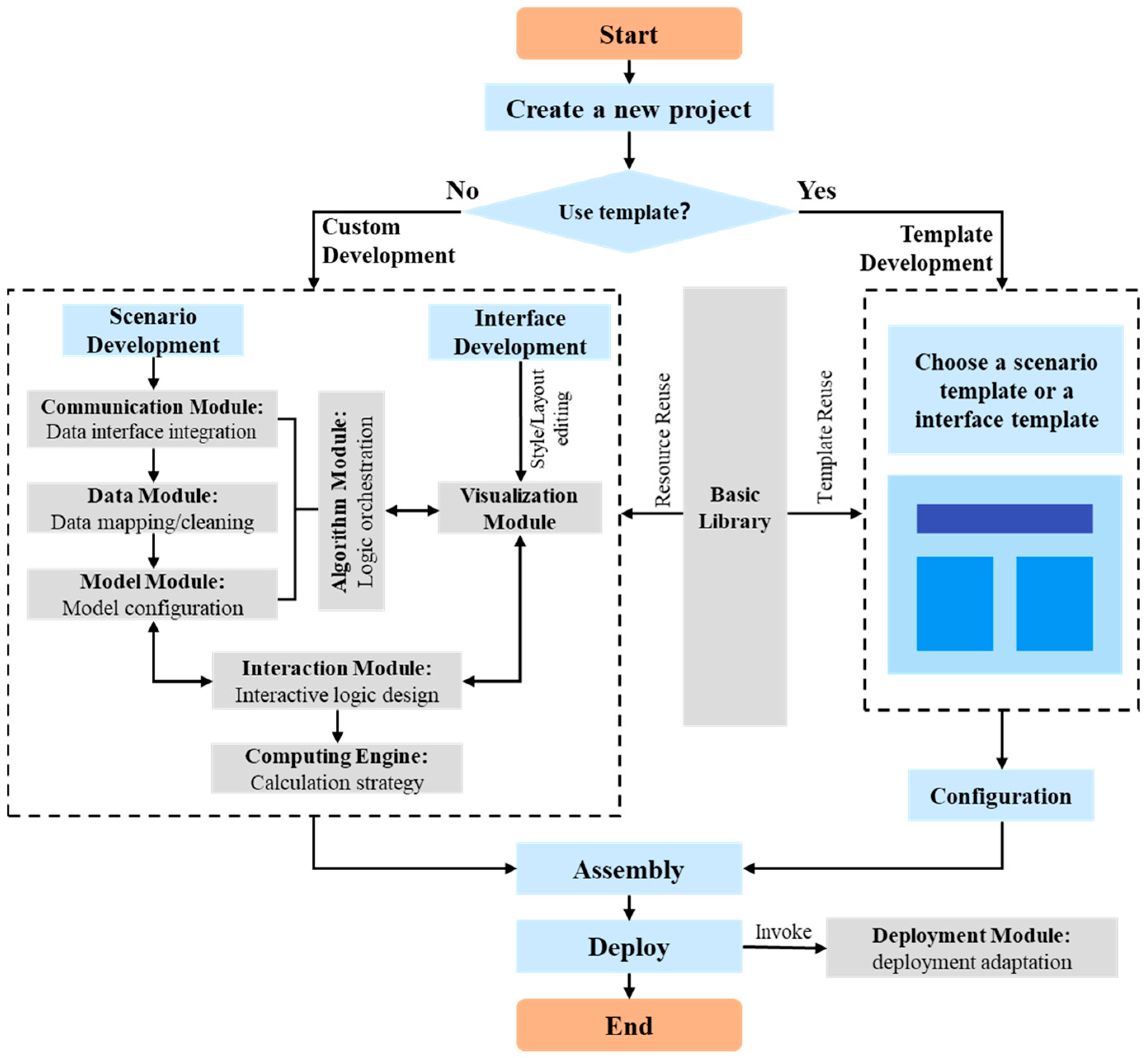

3.3. Workflow Based on MetaD-DT

- Template-based Development: This mode leverages the MetaD-DT’s existing template library and is particularly suitable for scenarios where the target digital twin application exhibits a high degree of similarity to pre-existing templates.

- Custom Development: This mode is designed for users with highly specialized or customized scenarios, allowing for the creation of unique application services beyond the scope of standard templates.

- Model editing is performed by calling the Model Module.

- Algorithm editing utilizes the Algorithm Module.

- The Data Module handles data editing and mapping.

- IoT access editing involves configuring the Communication Module.

4. Application Case of Engineering Equipment Digital Twin Based on MetaD-DT

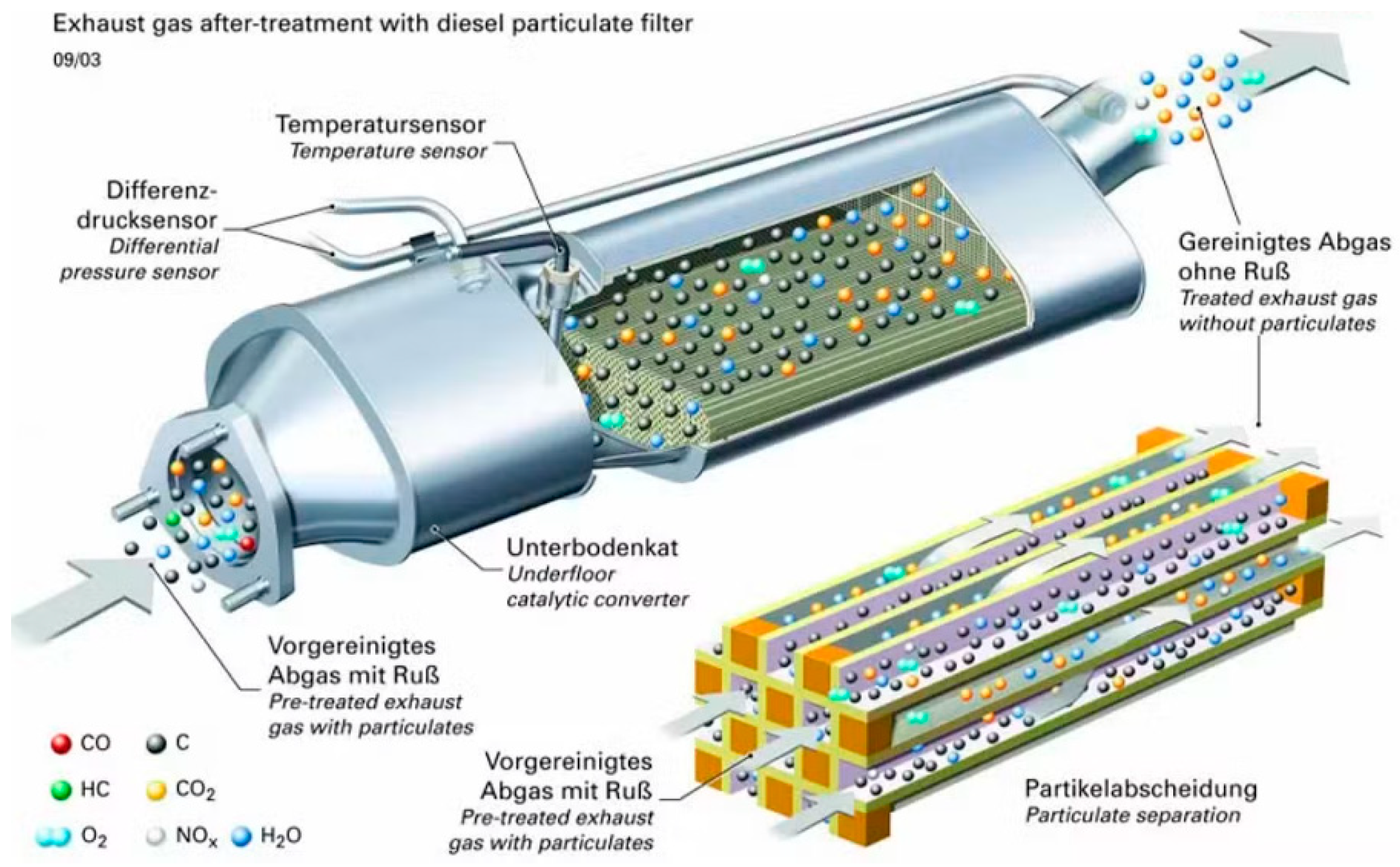

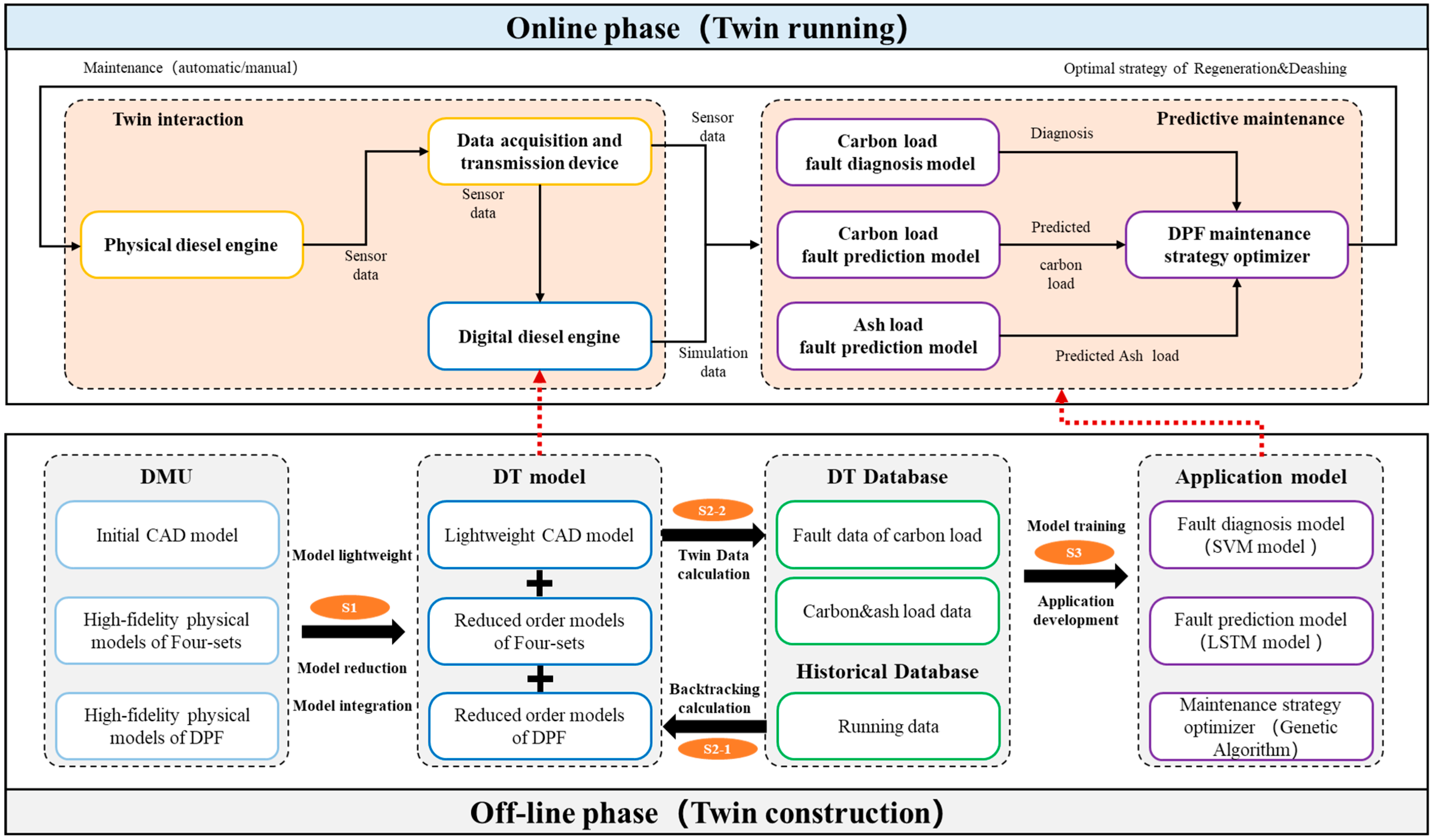

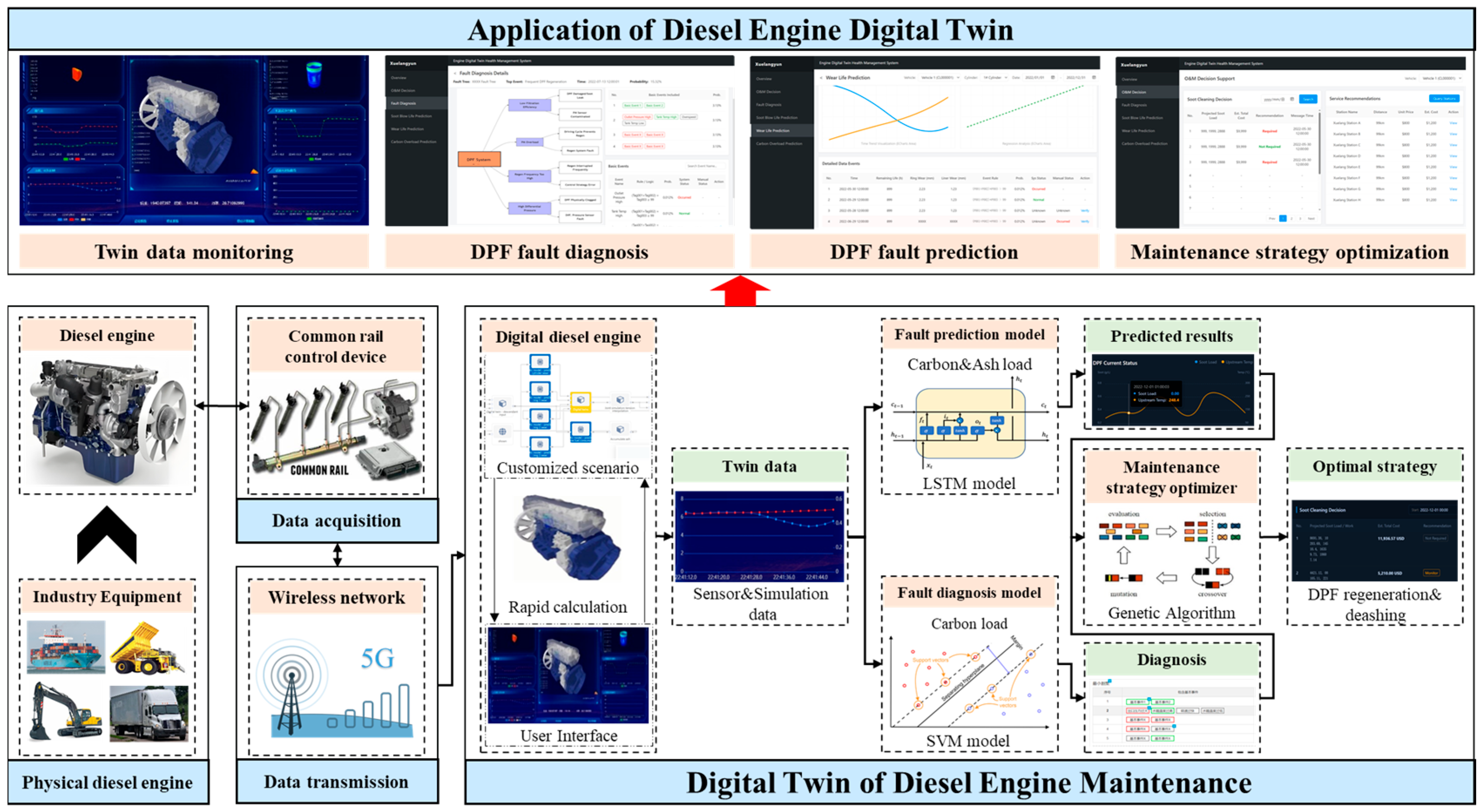

4.1. Case Study 1: Digital Twin-Based DPF Maintenance Optimization for Diesel Engines

4.1.1. Problem Description

4.1.2. Digital Twin Construction Route

- S1 Digital Twin Model Construction

- S2 Twin Data Generation

- S3 Predictive Maintenance Model Construction:

4.1.3. Digital Twin Application Effectiveness

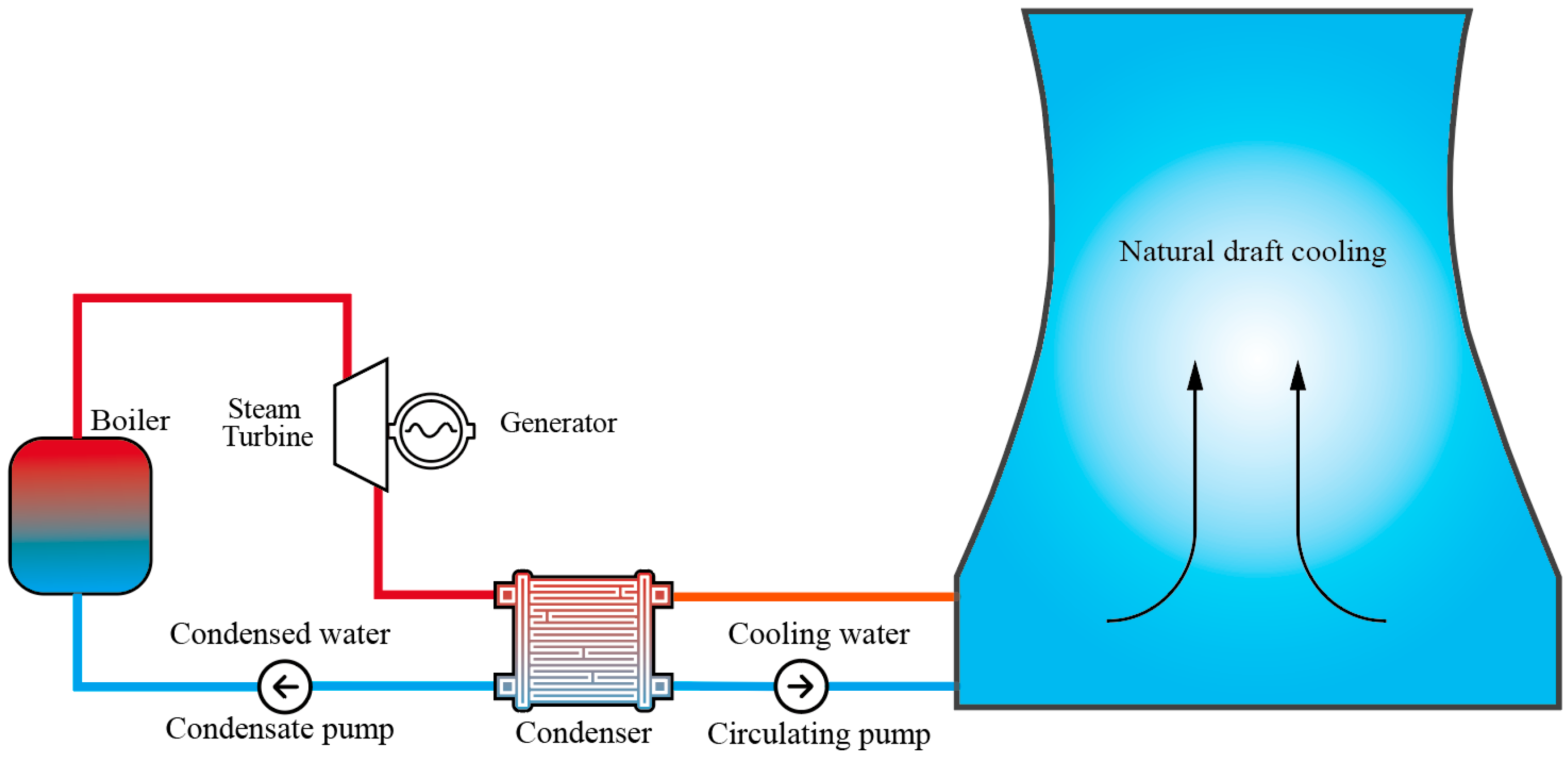

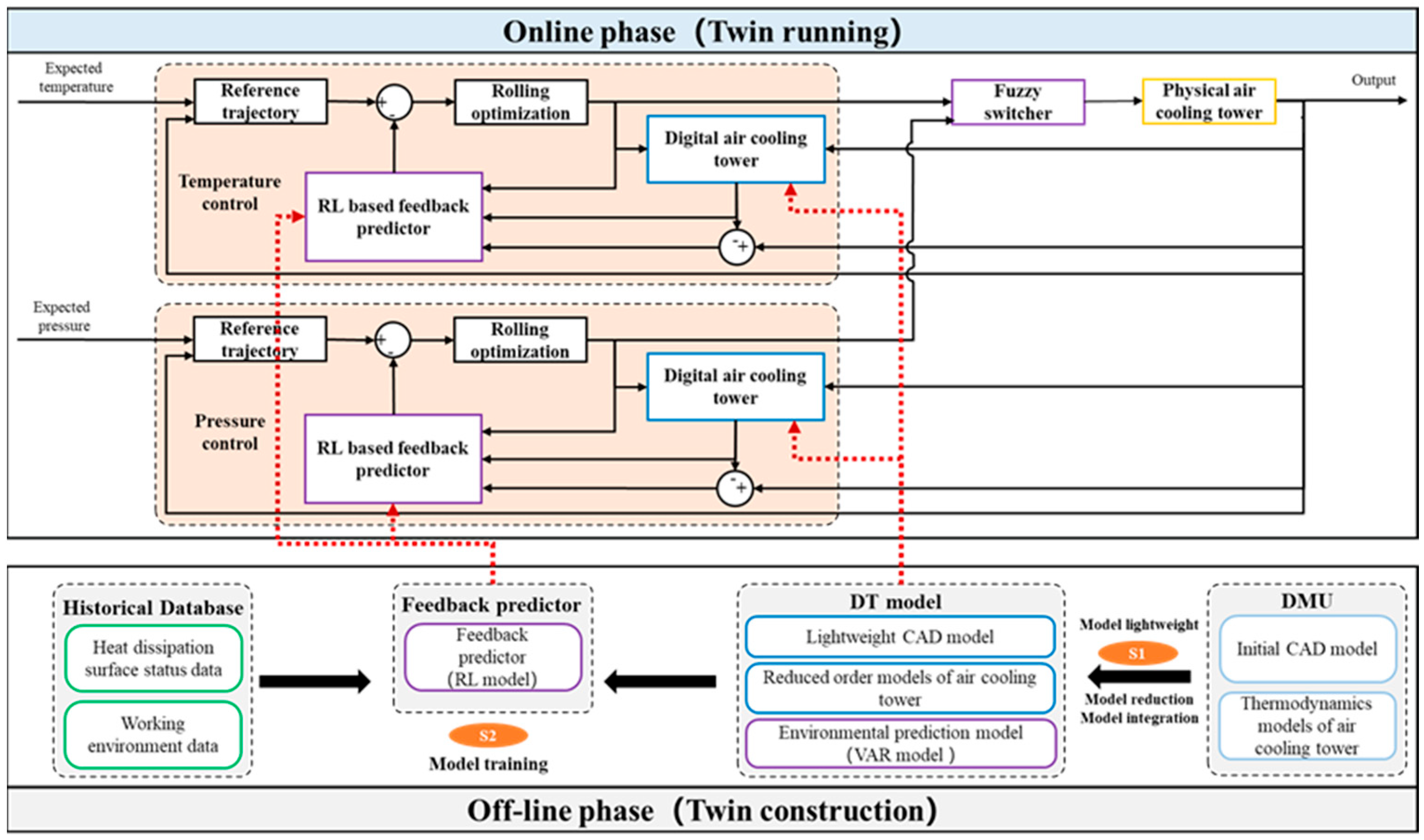

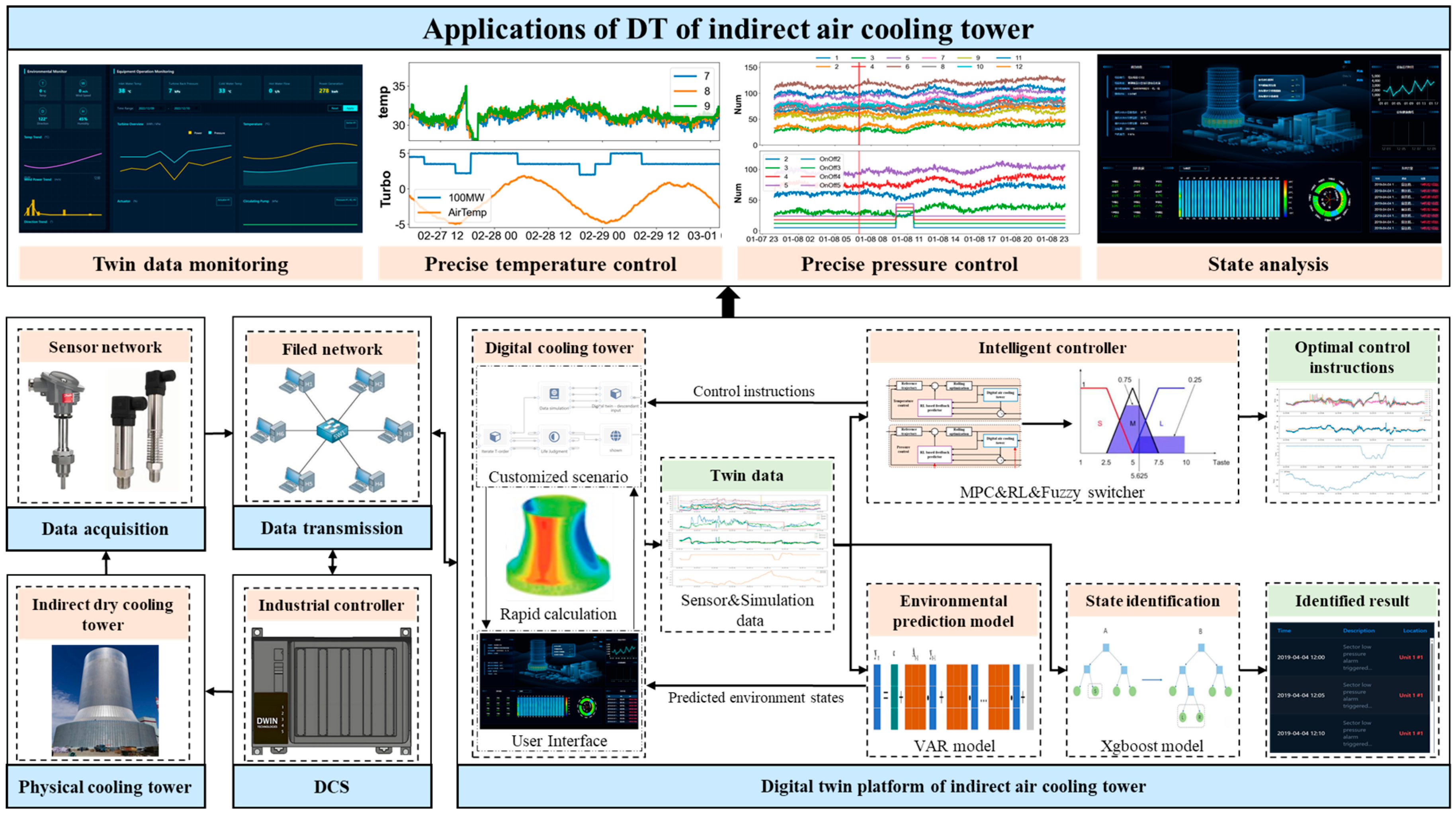

4.2. Case Study 2: Digital Twin-Based Control Optimization of IAC Towers for Thermal Power Plants

4.2.1. Problem Description

4.2.2. Digital Twin Construction Route

- Fundamental Control Architecture based on MPC:

- Digital Twin-based Hybrid Prediction Model:

- Reinforcement Learning-based Feedback Predictor:

4.2.3. Digital Twin Application Effectiveness

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CAE | Computer-Aided Engineering |

| CAN | Controller Area Network |

| DCS | Distributed Control System |

| DMOM | Design, Manufacturing, Operation, and Maintenance |

| DPF | Diesel Particulate Filter |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GEO-FNO | Geometry-Aware Fourier Neural Operator |

| GPU | Graphic Processing Unit |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| IAC | Indirect Air-Cooled |

| IDE | Integrated Development Environment |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NASEM | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, And Medicine |

| OPC UA | Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| POD | Proper Orthogonal Decomposition |

| O&M | Operation And Maintenance |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| ROM | Reduced-Order Model |

| SINDy | Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics |

| SSL | Secure Sockets Layer |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| WebGL | Web Graphics Library |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XR | Extended Reality |

References

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, C. Digital Twin Modeling Enabled Machine Tool Intelligence: A Review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tao, F.; Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Freiheit, T. Smart Manufacturing and Intelligent Manufacturing: A Comparative Review. Engineering 2021, 7, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, L.; Tan, Y.; Qiao, F. Engineering Management for High-End Equipment Intelligent Manufacturing. Front. Eng. Manag. 2018, 5, 420–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongming, G. High-Performance Manufacturing. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 2024, 6, 60201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baladeh, A.E.; Taghipour, S. Dynamic Multilevel Redundancy Allocation Optimization under Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2023 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Orlando, FL, USA, 23–26 January 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vrolijk, A.-P.; Deng, Y.; Olechowski, A. Connecting Design Iterations to Performance in Engineering Design. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doellken, M.; Zimmerer, C.; Matthiesen, S. Challenges Faced by Design Engineers When Considering Manufacturing in Design—An Interview Study. Proc. Des. Soc. Des. Conf. 2020, 1, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Hu, T.; Dong, L.; Ma, S. Digital Twin-Driven Manufacturing Equipment Development. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 83, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.I.-K.; Huang, H.; Xu, X. Digital Twin-Driven Smart Manufacturing: Connotation, Reference Model, Applications and Research Issues. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 61, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, J.F.; Afolalu, S.A.; Monye, S.I.; Adaramola, B.A. Overview of Maintenance Scope and Reliability in the Manufacturing Sector. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Driving Sustainable Development Goals (SEB4SDG 2024), Omu-Aran, Nigeria, 2–4 April 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ni, J.; Singh, J.; Jiang, B.; Azamfar, M.; Feng, J. Intelligent Maintenance Systems and Predictive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek, M.; Gola, A. Maintenance 4.0 Technologies for Sustainable Manufacturing—An Overview. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M. Origins of the Digital Twin Concept. 2016. Available online: https://www.spaceis.cn/nd.jsp?id=78 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. ISBN 978-3-319-38756-7. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Engineering; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate; Board on Life Sciences; Computer Science and Telecommunications Board; Committee on Applied and Theoretical Statistics; Board on Mathematical Sciences and Analytics; Committee on Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins. Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-0-309-70042-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tuegel, E.J.; Ingraffea, A.R.; Eason, T.G.; Spottswood, S.M. Reengineering Aircraft Structural Life Prediction Using a Digital Twin. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2011, 2011, 154798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaessgen, E.; Stargel, D. The Digital Twin Paradigm for Future NASA and U.S. Air Force Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 April 2012; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phanden, R.K.; Sharma, P.; Dubey, A. A Review on Simulation in Digital Twin for Aerospace, Manufacturing and Robotics. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. The Increasing Potential and Challenges of Digital Twins. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, Q.; Tao, F. A Multi-Scale Modeling Method for Digital Twin Shop-Floor. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, Z. Self-Learning Time-Varying Digital Twin System for Intelligent Monitoring of Automatic Production Line. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2456, 12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Intelligent Digital Twin (iDT) for Supply Chain Stress-Testing, Resilience, and Viability. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 263, 108938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Miao, T.; Liu, J.; Xiong, H. The Connotation of Digital Twin, and the Construction and Application Method of Shop-Floor Digital Twin. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 68, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.; Mikkelsen, P.H.; Gomes, C.; Larsen, P.G. Survey on Open-Source Digital Twin Frameworks–A Case Study Approach. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2024, 54, 929–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, S.; Martín, C.; Robles, J.; Rubio, B.; Díaz, M.; Perea, R.G.; Montesinos, P.; Poyato, E.C. Integrating FMI and ML/AI Models on the Open-Source Digital Twin Framework OpenTwins. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2024, 54, 1470–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fur, S.; Heithoff, M.; Michael, J.; Netz, L.; Pfeiffer, J.; Rumpe, B.; Wortmann, A. Sustainable Digital Twin Engineering for the Internet of Production. In Digital Twin Driven Intelligent Systems and Emerging Metaverse; Karaarslan, E., Aydin, Ö., Cali, Ü., Challenger, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 101–121. ISBN 978-981-99-0252-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Sun, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; et al. makeTwin: A Reference Architecture for Digital Twin Software Platform. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, H.; Cui, L. Frequency-Chirprate Synchrosqueezing-Based Scaling Chirplet Transform for Wind Turbine Nonstationary Fault Feature Time–Frequency Representation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 209, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Niu, Y.; Ma, L.; Wu, H.; Shen, H.; Wang, T. Local Entropy Selection Scaling-Extracting Chirplet Transform for Enhanced Time-Frequency Analysis and Precise State Estimation in Reliability-Focused Fault Diagnosis of Non-Stationary Signals. Eksploat. Niezawodn.-Maint. Reliab. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H.; Xu, C. Review of Digital Twin about Concepts, Technologies, and Industrial Applications. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. Complex Product Manufacturing and Operation and Maintenance Integration Based on Digital Twin. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falekas, G.; Karlis, A. Digital Twin in Electrical Machine Control and Predictive Maintenance: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. Energies 2021, 14, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wan, J.; Deng, P. Machine-Learning-Driven Digital Twin for Lifecycle Management of Complex Equipment. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2022, 10, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingyu, L.; Weixi, J.; Chen, C.; Su, X. Maintenance Architecture Design of Equipment Operation and Maintenance System Based on Digital Twins. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B 2024, 238, 1971–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Hu, W.; Liao, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, J. A High-End Equipment Real-Time Virtual-Real Interaction Implementation Based on Digital Twin. In Advances in Mechanical Design, Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Mechanical Design (2021 ICMD), Changsha, China, 11–13 August 2021; Tan, J., Liu, Y., Huang, H.-Z., Yu, J., Wang, Z., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1949–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lai, X.; He, X.; Qiu, Y.; Song, X. Building a Trustworthy Product-Level Shape-Performance Integrated Digital Twin With Multifidelity Surrogate Model. J. Mech. Des. 2022, 144, 031703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, F.; Lloyd, A.L.; Flores, K.B. Hybrid Modeling and Prediction of Dynamical Systems. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Gong, Y.; Luo, D.; Yue, L. Improved Multi-Fidelity Simulation-Based Optimisation: Application in a Digital Twin Shop Floor. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 1016–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, S.; Lv, Z.; Wang, F.; Olofsson, T. Application of Digital Twins and Metaverse in the Field of Fluid Machinery Pumps and Fans: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, J.; Sun, G.; Wu, T.; Yu, L.; Zhao, X. A Novel Digital Twin Approach Based on Deep Multimodal Information Fusion for Aero-Engine Fault Diagnosis. Energy 2023, 270, 126894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ding, G.; Xie, J.; Li, Z.; Qin, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K. Multi-Stage Cyber-Physical Fusion Methods for Supporting Equipment’s Digital Twin Applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 5783–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C. Advancements and Challenges of Digital Twins in Industry. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsakin, R.; Mehandjiev, N.; Marin, C.A. Towards Adaptive Digital Twins Architecture. Comput. Ind. 2023, 149, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. A New Perspective on Digital Twin-Based Mechanical Design in Industrial Engineering. Innov. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sui, F. Digital Twin-Driven Product Design, Manufacturing and Service with Big Data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Jian, H.; Shi, Y. Digital Twin Technologies for Turbomachinery in a Life Cycle Perspective: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muctadir, H.M.; Manrique Negrin, D.A.; Gunasekaran, R.; Cleophas, L.; van den Brand, M.; Haverkort, B.R. Current Trends in Digital Twin Development, Maintenance, and Operation: An Interview Study. Softw. Syst. Model. 2024, 23, 1275–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Fang, H.; Liu, H.; Tong, Y.; Yang, D.; Ouyang, X. Physics-Informed Neural Network for Solving Hydrodynamic Lubrication Characteristics of Piston Pump Slipper Pair; River Publishers: Aalborg, Denmark, 2025; ISBN 978-87-438-0825-1. [Google Scholar]

- Söderäng, E.; Hautala, S.; Mikulski, M.; Storm, X.; Niemi, S. Development of a Digital Twin for Real-Time Simulation of a Combustion Engine-Based Power Plant with Battery Storage and Grid Coupling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 266, 115793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Liu, Q.; Pi, S.; Xiao, Y. Real-Time Machining Data Application and Service Based on IMT Digital Twin. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.E.B. Real-Time Event-Based Platform for the Development of Digital Twin Applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 116, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monek, G.D.; Fischer, S. Expert Twin: A Digital Twin with an Integrated Fuzzy-Based Decision-Making Module. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2025, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, K.; Segundo, B. The Role of Computational Science in Digital Twins. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, C.; Ma, S. Edge Computing-Based Real-Time Scheduling for Digital Twin Flexible Job Shop with Variable Time Window. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, T.; Abonyi, J. Integration of Real-Time Locating Systems into Digital Twins. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 20, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuts, V.; Otto, T.; Tähemaa, T.; Bondarenko, Y. Digital Twin Based Synchronised Control and Simulation of the Industrial Robotic Cell Using Virtual Reality. J. Mach. Eng. 2019, 19, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipper, H. Real-Time-Capable Synchronization of Digital Twins. IFAC-Pap. 2021, 54, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Data Assimilation for Simulation-Based Real-Time Prediction/Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 Annual Modeling and Simulation Conference (ANNSIM), San Diego, CA, USA, 18–20 July 2022; pp. 404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, L.; Galletti, C.; Parente, A. Self-Updating Digital Twin of a Hydrogen-Powered Furnace Using Data Assimilation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvetti, D.; Mêda, P.; Hjelseth, E.; de Sousa, H. Incremental Digital Twin Framework: A Design Science Research Approach for Practical Deployment. Autom. Constr. 2025, 170, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X. Learn to Update Digital Twins with Incremental Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Networked AI Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Yongqi, Z.; Huaxin, Z.; Dragoslav, S.; Maosen, C. Digital Twin-Driven Intelligent Construction: Features and Trends. Sdhm Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 2021, 15, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, X. Predictive Maintenance for Switch Machine Based on Digital Twins. Information 2021, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Song, X.; Xu, D. State Perception and Prediction of Digital Twin Based on Proxy Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 36064–36072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, E.V. Design Technology and AI-Based Decision Making Model for Digital Twin Engineering. Future Internet 2022, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.; Varshney, P.K. Human-Machine Collaboration for Smart Decision Making: Current Trends and Future Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th International Conference on Collaboration and Internet Computing, CIC 2022, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–16 December 2022; pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, P.; Hegedűs-Kuti, J.; Szőlősi, J.; Farkas, G. Real-Time Data Visualization of Welding Robot Data and Preparation for Future of Digital Twin System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Han, Z.; Zheng, R. Digital Twin in Smart Manufacturing: Remote Control and Virtual Machining Using VR and AR Technologies. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2022, 65, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, J.; Guo, Y.; Dang, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Exploring Geospatial Digital Twins: A Novel Panorama-Based Method with Enhanced Representation of Virtual Geographic Scenes in Virtual Reality (VR). Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 2301–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Singh, S.; Uddin, R. Rizwan-uddin XR and Digital Twins, and Their Role in Human Factor Studies. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1359688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tu, X.; Autiosalo, J.; Ala-Laurinaho, R.; Mattila, J.; Salminen, P.; Tammi, K. Extended Reality Application Framework for a Digital-Twin-Based Smart Crane. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.; Lobov, A.; Lanz, M. Emotions-Aware Digital Twins for Manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Cai, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Chen, P.; Zheng, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, J. Investigation of Diesel Particulate Filter Performance under Typical Failure Conditions. Energy 2024, 311, 133337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is a Diesel Particulate Filter, or DPF? Available online: https://www.drive.com.au/news/what-is-a-diesel-particulate-filter-or-dpf/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Park, G.; Park, S.; Hwang, T.; Oh, S.; Lee, S. A Study on the Impact of DPF Failure on Diesel Vehicles Emissions of Particulate Matter. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Nan, S. A Comprehensive Review of Predictive Control Strategies in Heating, Ventilation, and Air-Conditioning (HVAC): Model-Free VS Model. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 110013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Simulation Platforms (e.g., Ansys Twin Builder) | IoT Platforms (e.g., Siemens MindSphere) | MetaD-DT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | High-fidelity Physics (CAE) | Data Connectivity & Visualization | Mechanism–Data Fusion & O&M |

| Model Support | Strong in Physics | Strong in Data | Hybrid: Native support for ROMs and AI models |

| Customization | Low: Closed ecosystem; hard to modify core algorithms. | Medium: Standard widgets; limited algorithmic flexibility. | High: Specific for engineering equipment customization (also template-based) |

| Deployment | Workstation/Server-based | Cloud-based (SaaS) | Edge–Cloud Collaborative (Containerized) |

| Requirement | Key Modules | Implementation Mechanism | Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism–Data Fusion Modeling | Model Module Algorithm Module | Embedded ROM Engine: Fuses physics-based constraints with data-driven correction layers using standardized FMU interfaces. | Prediction Accuracy Convergence Speed Generalization Error |

| Real-time Computing & Synchronization | Computing Engine Communication Module | Edge–Cloud Scheduling: Offloads training to cloud while executing inference on edge via GPU-accelerated containers; employs event-driven synchronization. | End-to-End Latency Synchronization Error Throughput |

| Data Assimilation & Evolution | Data Module Algorithm Module | Rolling-Window Update: Continuously assimilates new sensor data into the historical database to trigger online parameter tuning of the digital twin. | Update Frequency Data Completeness Model Drift Rate |

| Predictive Maintenance & Decision | Algorithm Module Interaction Module | Optimization Solver: Integrates Rule Engines to generate maintenance strategies based on predicted states. | False Alarm Rate Decision Confidence O&M Cost Reduction |

| Human–Computer Interaction | Visualization Module Interaction Module | Scene Graph Rendering: Decouples backend logic from WebGL-based 3D frontend; supports bi-directional command transmission via WebSocket. | Rendering Frame Rate Interaction Response Time Usability Score |

| Model Name | Algorithm Strategy | Input Variables | Output | Accuracy 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soot Oxidation Rate Model | POD-RBF |

| Residual Soot Mass | Train: 99.99% Test: 99.99% |

| Cylinder Liner Wear Model | POD-RBF |

| Liner Wear Amount | Train: 99.75% Test: 99.51% |

| DPF Pressure Drop Model | GEO-FNO |

| DPF Pressure Drop | Train: 99.57% Test: 90.51% |

| DPF Temperature Field Model | GEO-FNO |

| Temperature Distribution Field | Train: 98.28% Test: 96.50% |

| Performance Metric | Segmented Control: PID + Manual | MetaD-DT: MPC + RL + Fusion Model |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cooling Water Outlet Temperature Stability | Unstable in Harsh Conditions: Stable weather: ±1∼±2 °C Complex weather (Winter/Gale): ±2∼±5 °C Extreme cases: >±8 °C | High Precision: Consistently maintained within ±0.5 °C across varying load and weather conditions. |

| 2. Sector Surface Temperature Difference (Thermal Uniformity) | High Variance: Stable weather:<5 °C Complex weather: 8 °C∼15 °C Extreme cases: >20 °C (High freezing risk) | High Uniformity: Temperature difference reduced by approx. 8 °C, Significantly lower risk of tube bundle freezing. |

| 3. System Critical Low Temperature (Anti-freezing Threshold) | Conservative (Energy Waste): Setpoint must be kept >7 °C to prevent freezing, reducing turbine efficiency. | Optimized (Energy Saving): Threshold lowered by 5 °C. Safe operation achievable at 1∼2 °C. |

| 4. Labor Dependency | High: Heavy reliance on manual tuning during weather changes; high workload and operator stress. | Low: Fully automated closed-loop control; manual intervention is rarely required. |

| 5. Technical Complexity & Cost | Low: Simple mechanism; mature technology; directly deployed on Edge Controllers (PLC). | High: Requires high-fidelity modeling, massive data for RL training, and cloud–edge deployment coordination. |

| 6. Overall Economic Benefit | Standard: Limited by conservative operation margins. | High: Significant energy savings and extended equipment lifespan. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, T.; Gu, Y. MetaD-DT: A Reference Architecture Enabling Digital Twin Development for Complex Engineering Equipment. Electronics 2026, 15, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010038

Gao H, Wang F, Zhao T, Gu Y. MetaD-DT: A Reference Architecture Enabling Digital Twin Development for Complex Engineering Equipment. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Hanyu, Feng Wang, Taoping Zhao, and Yi Gu. 2026. "MetaD-DT: A Reference Architecture Enabling Digital Twin Development for Complex Engineering Equipment" Electronics 15, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010038

APA StyleGao, H., Wang, F., Zhao, T., & Gu, Y. (2026). MetaD-DT: A Reference Architecture Enabling Digital Twin Development for Complex Engineering Equipment. Electronics, 15(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010038