Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping: An Interpretable Visualization Framework for MRI-Based Brain Age Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Experiments

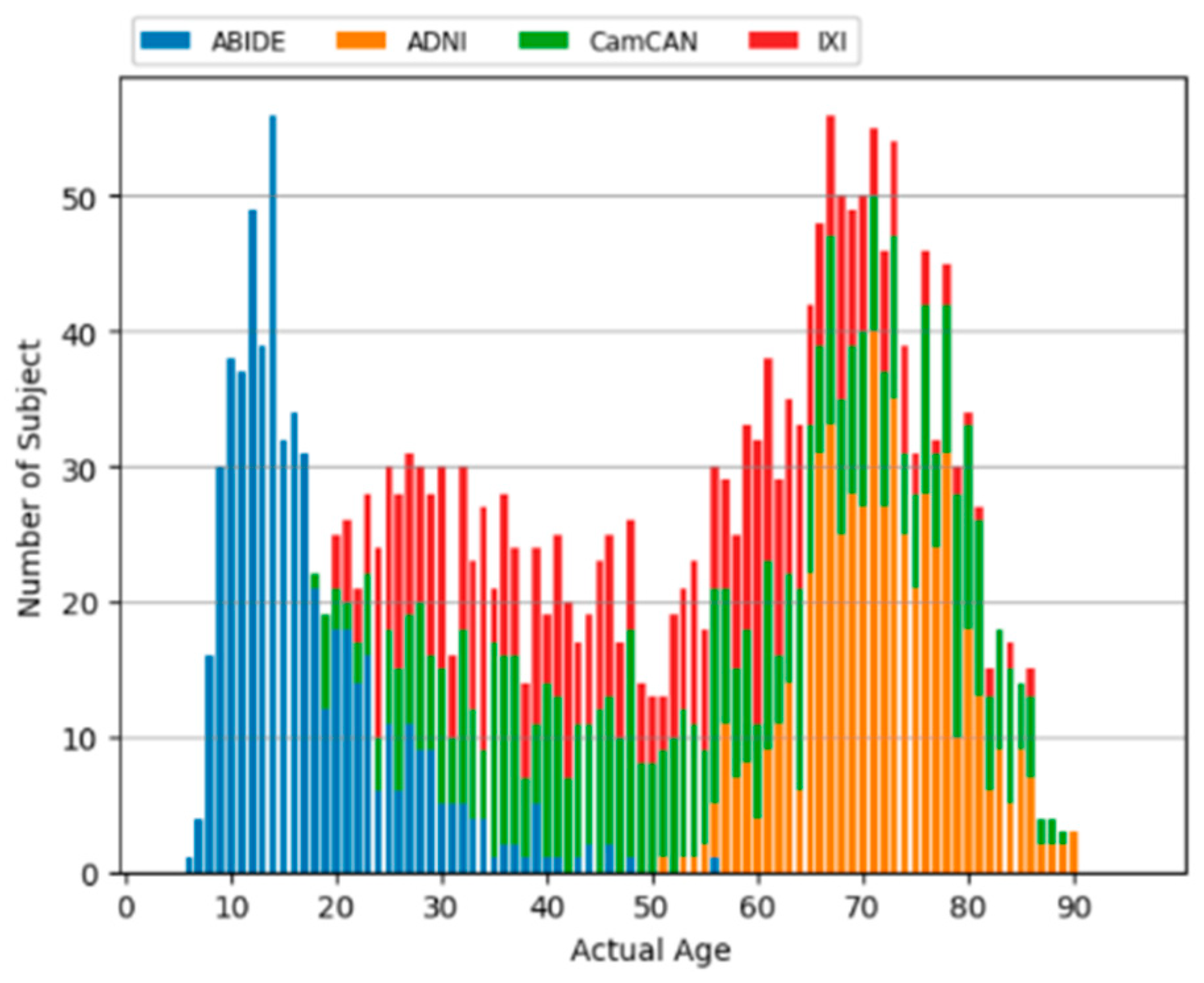

3.1. Data Sets

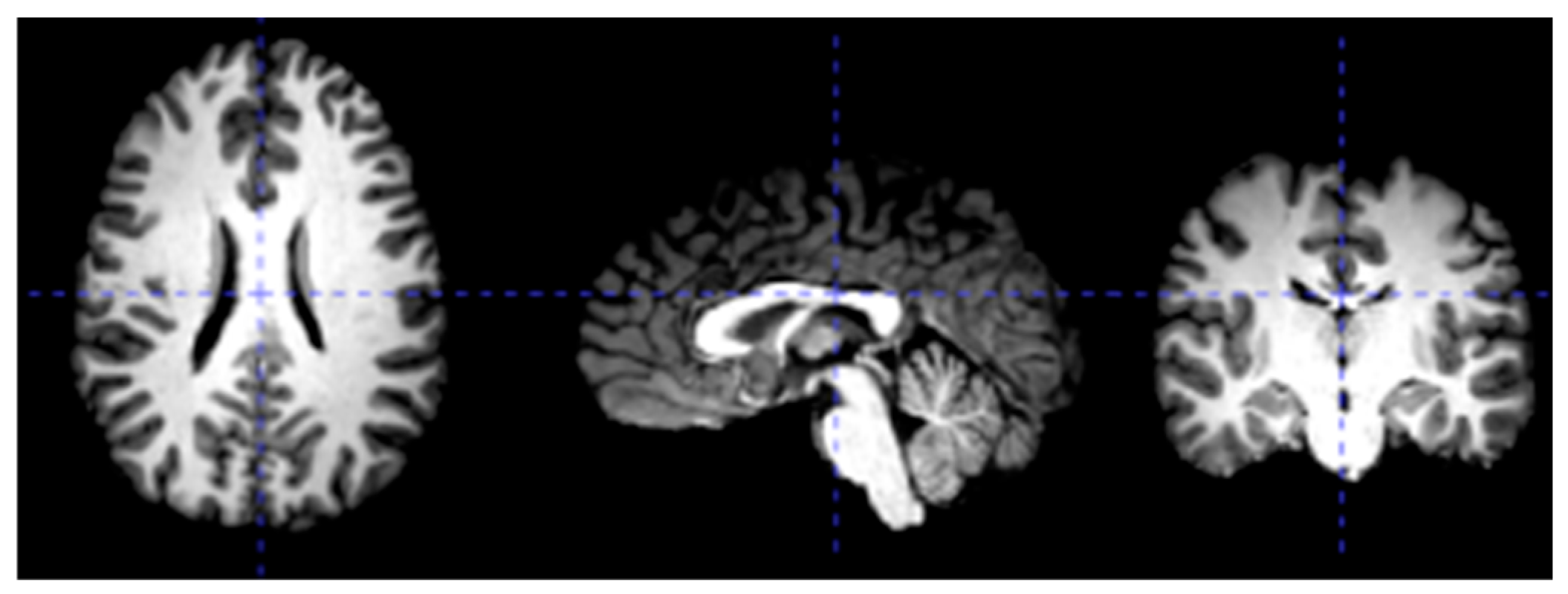

3.2. Data Preprocessing

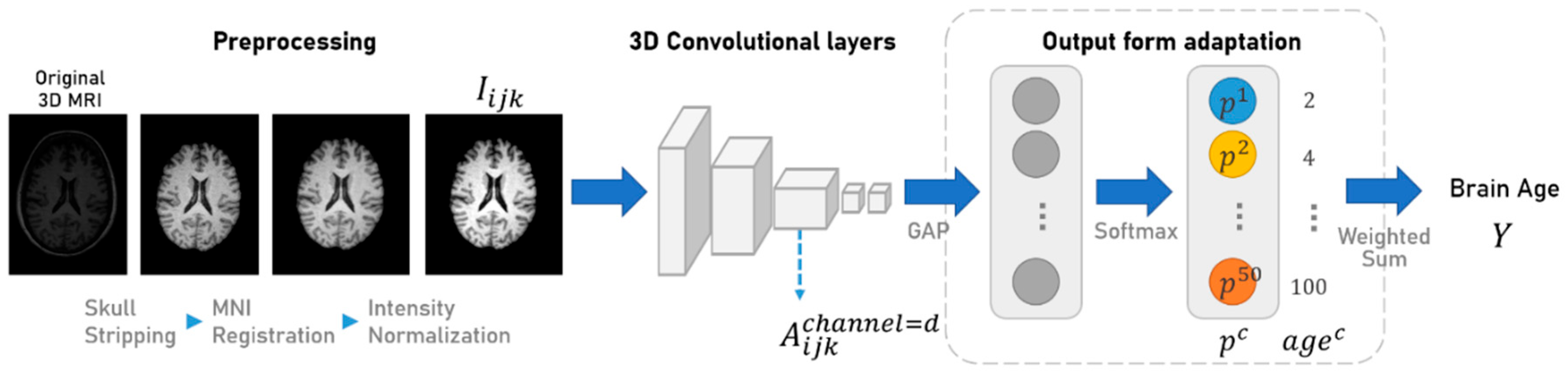

3.3. Model Architecture Design

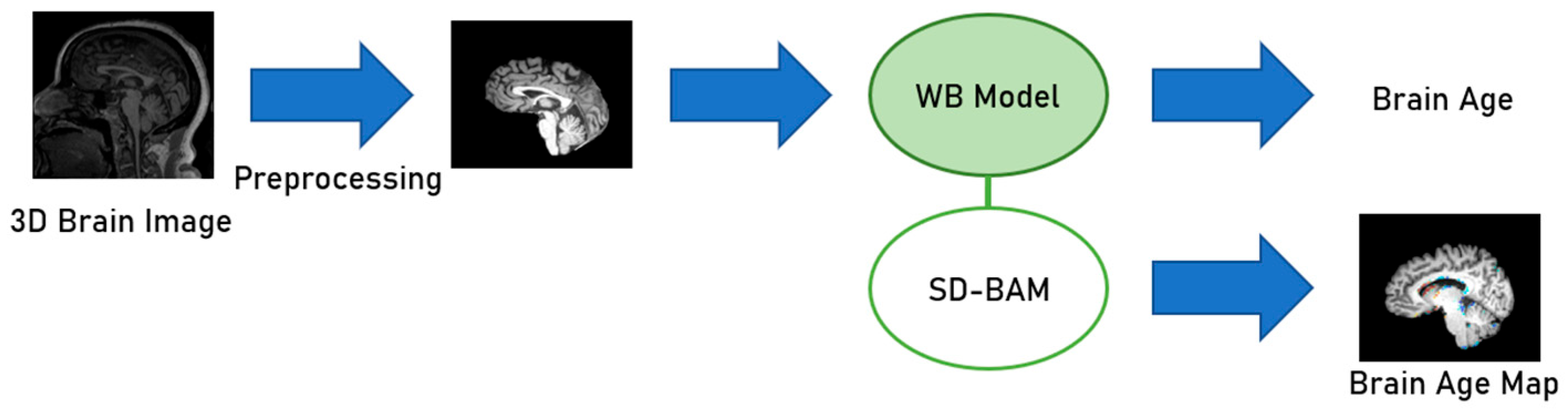

3.4. Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping

3.5. Training Method

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Models Evaluation Methods

4.2. SD-BAM Evaluation Method

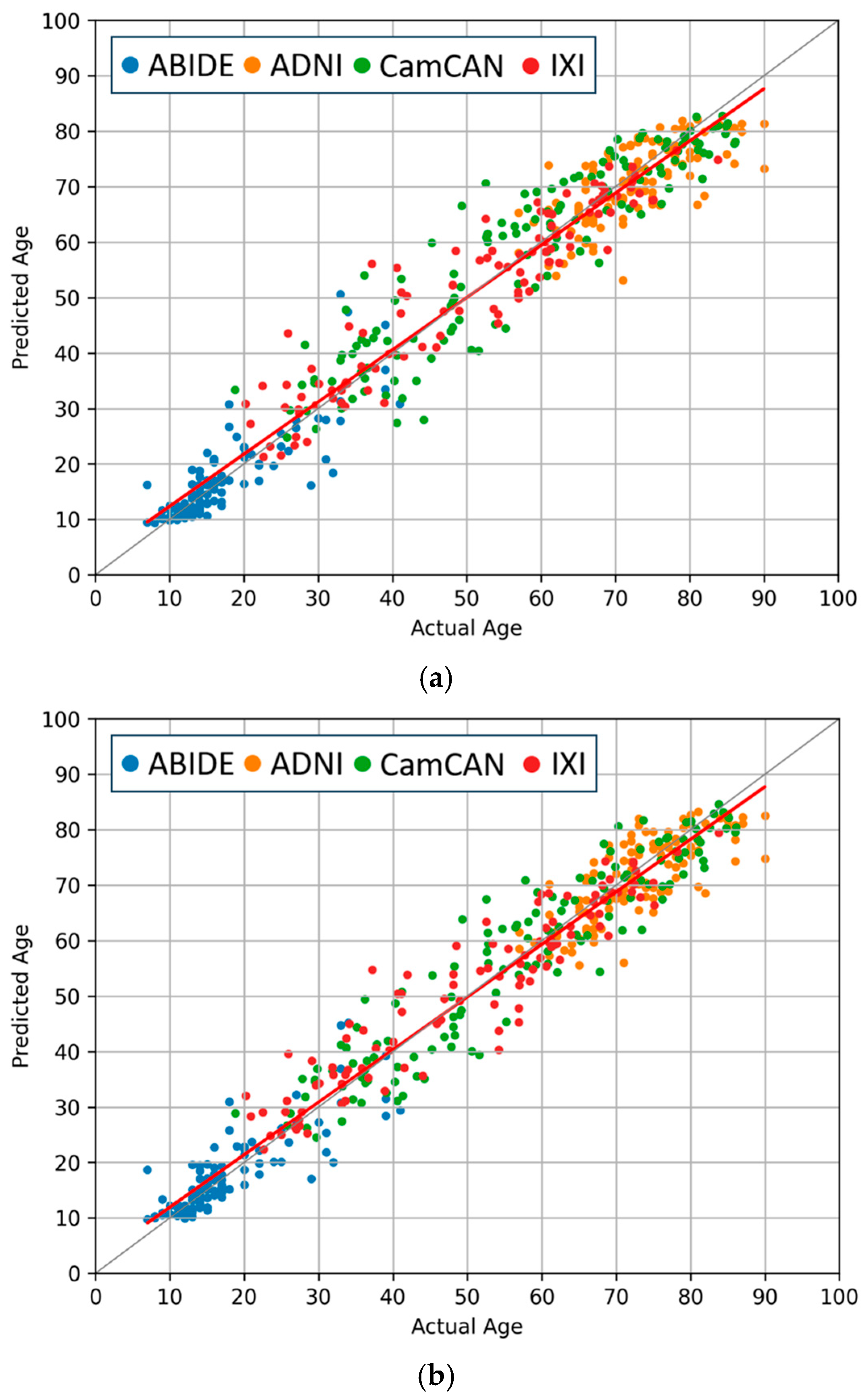

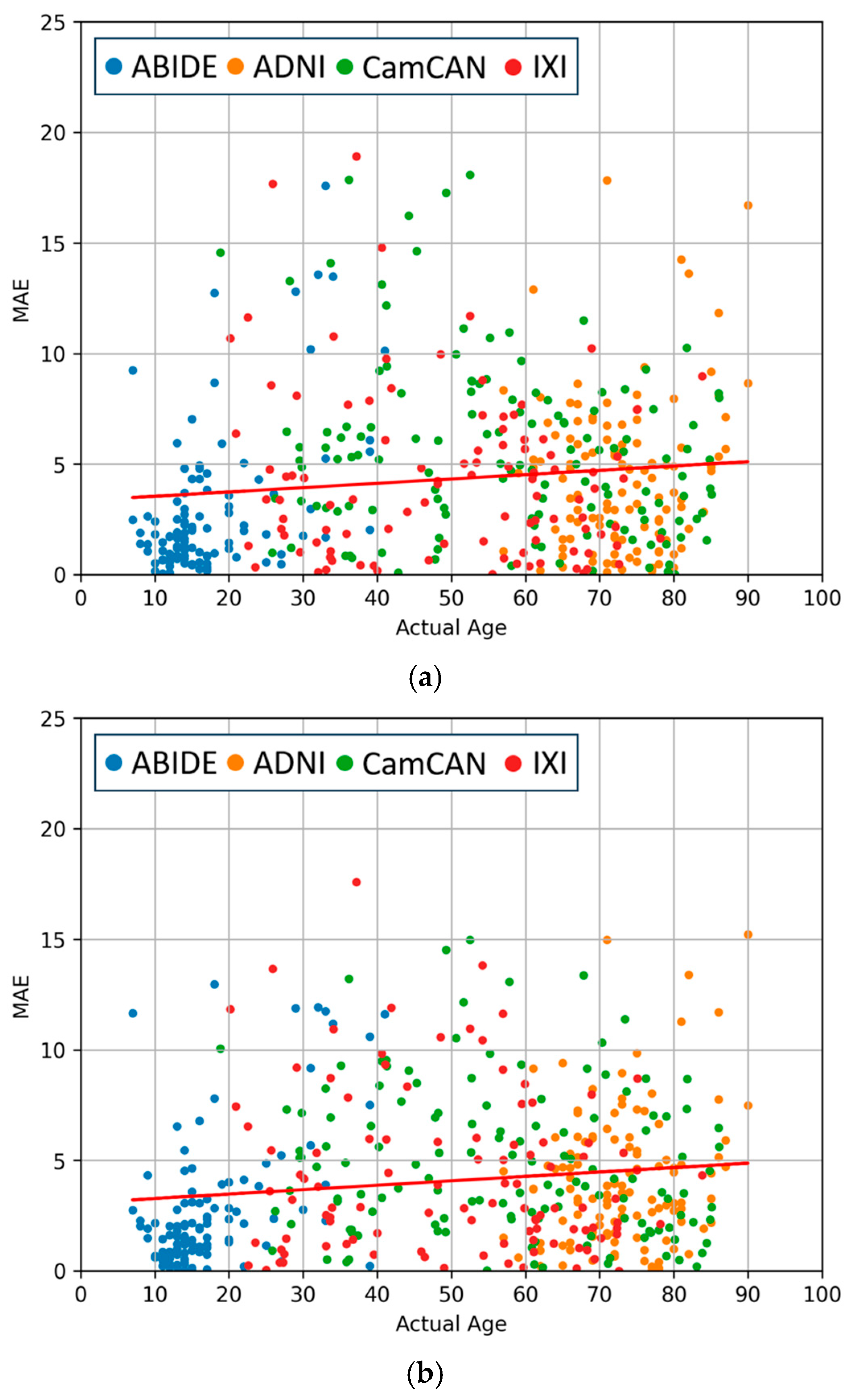

4.3. Comparisons of Regression and Softmax Performance

4.4. Evaluation of Data Augmentation

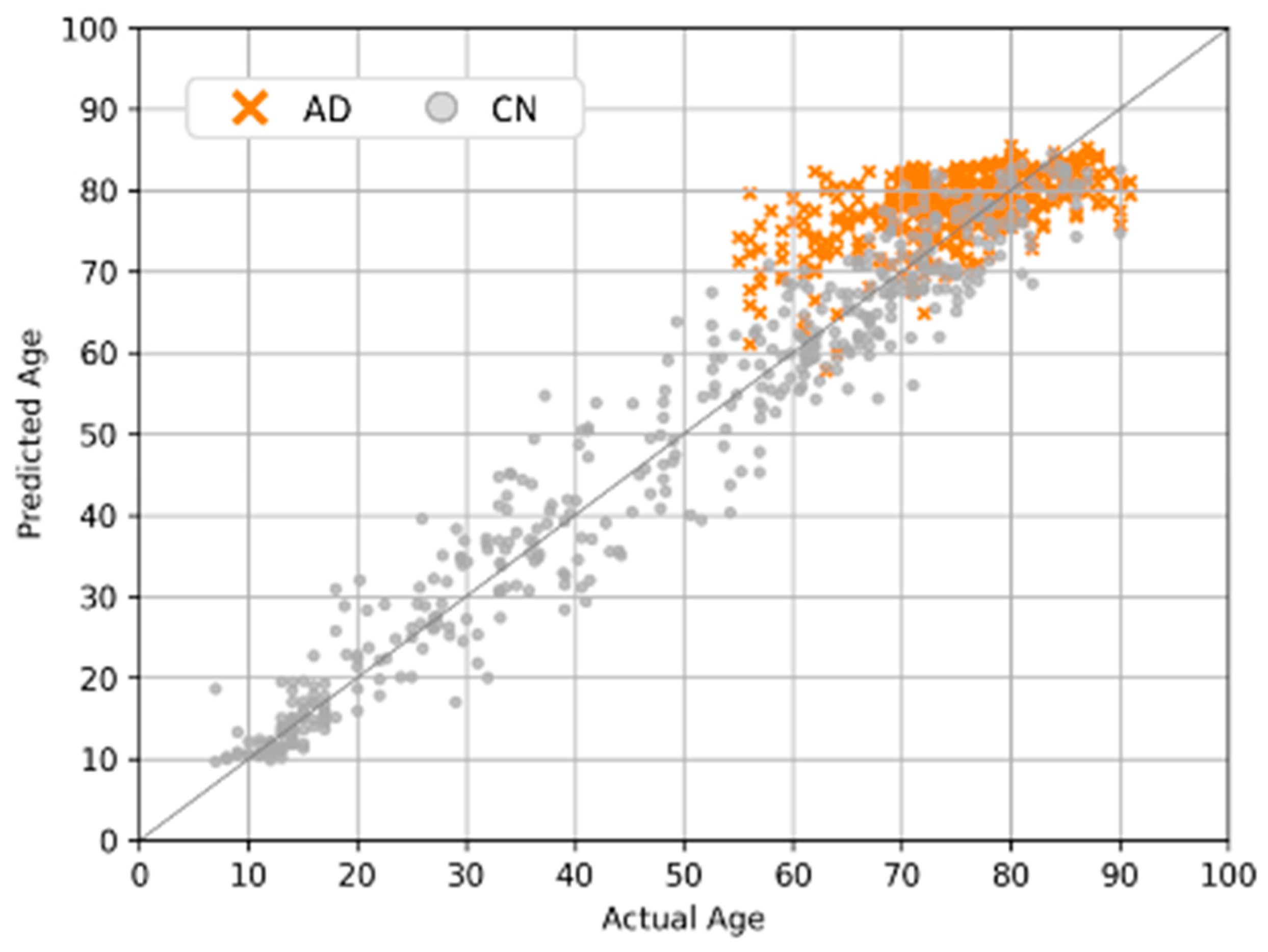

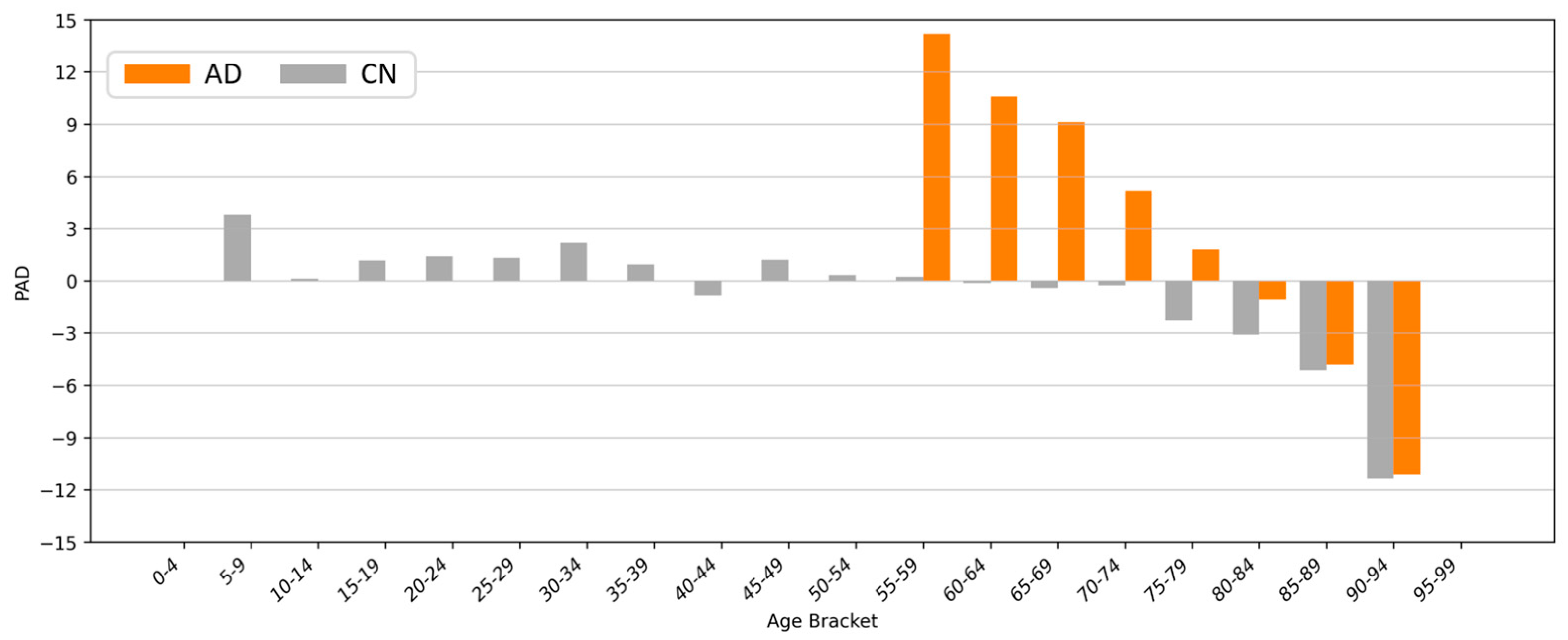

4.5. Clinical Applications and Efficacy Assessment

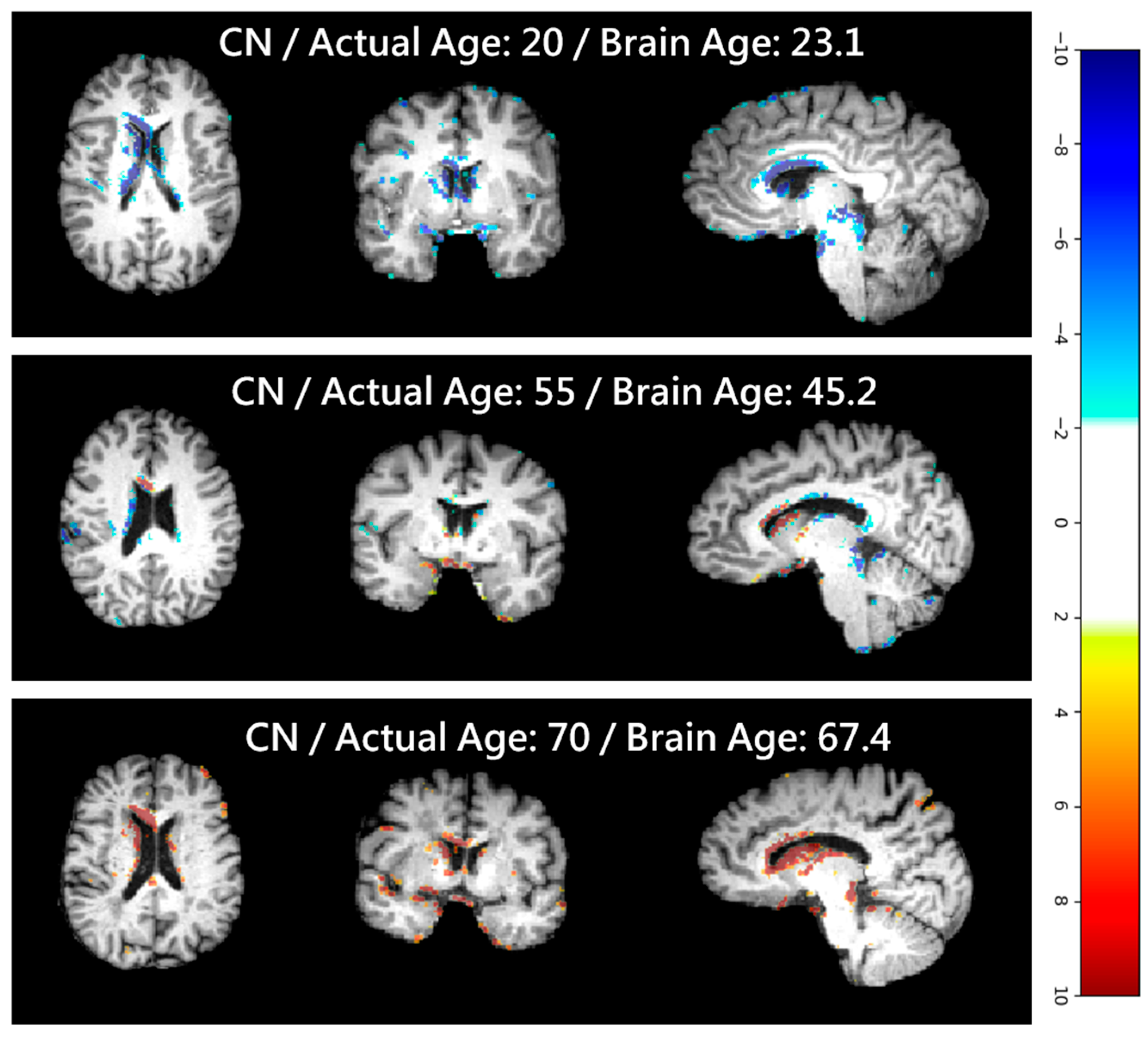

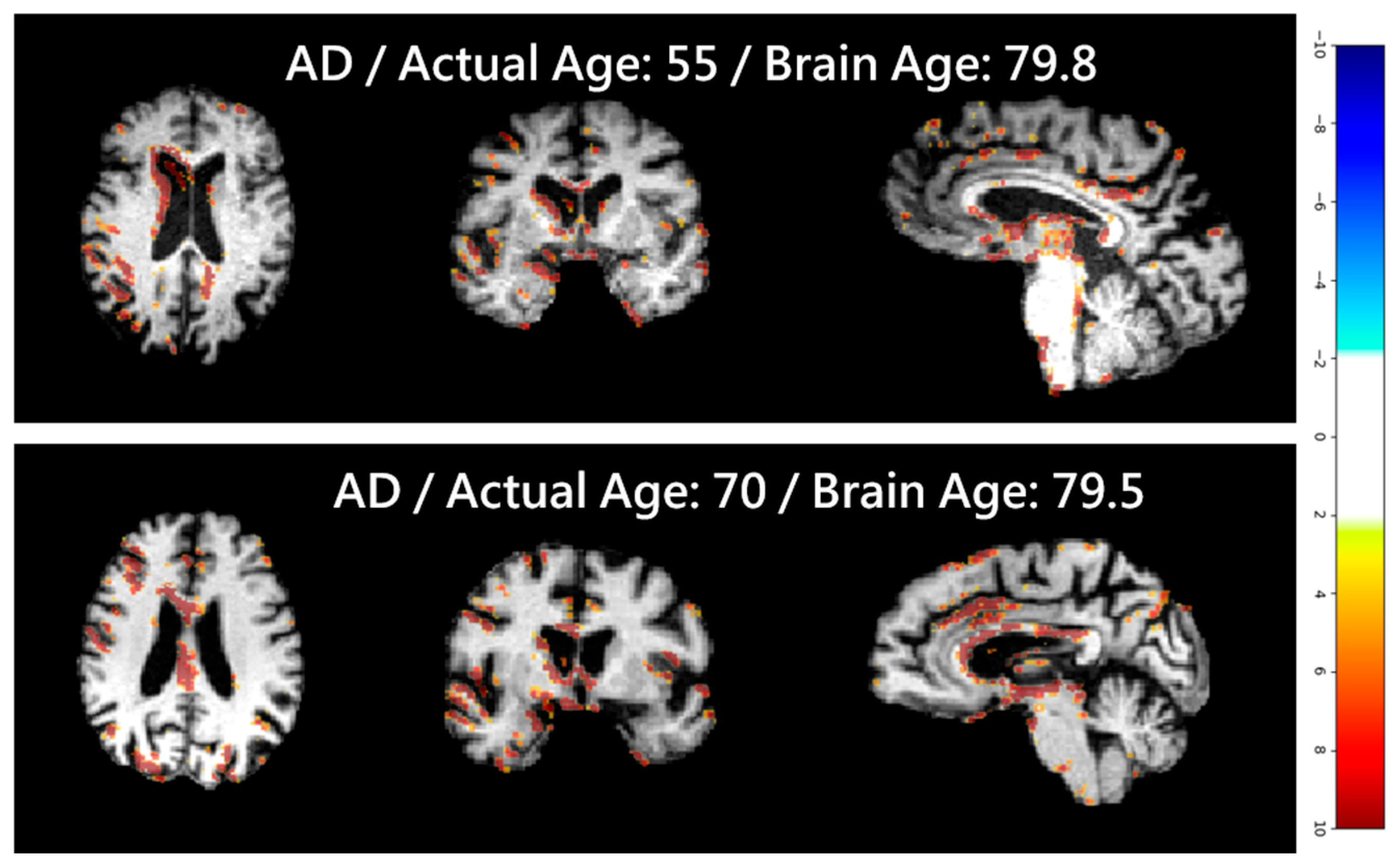

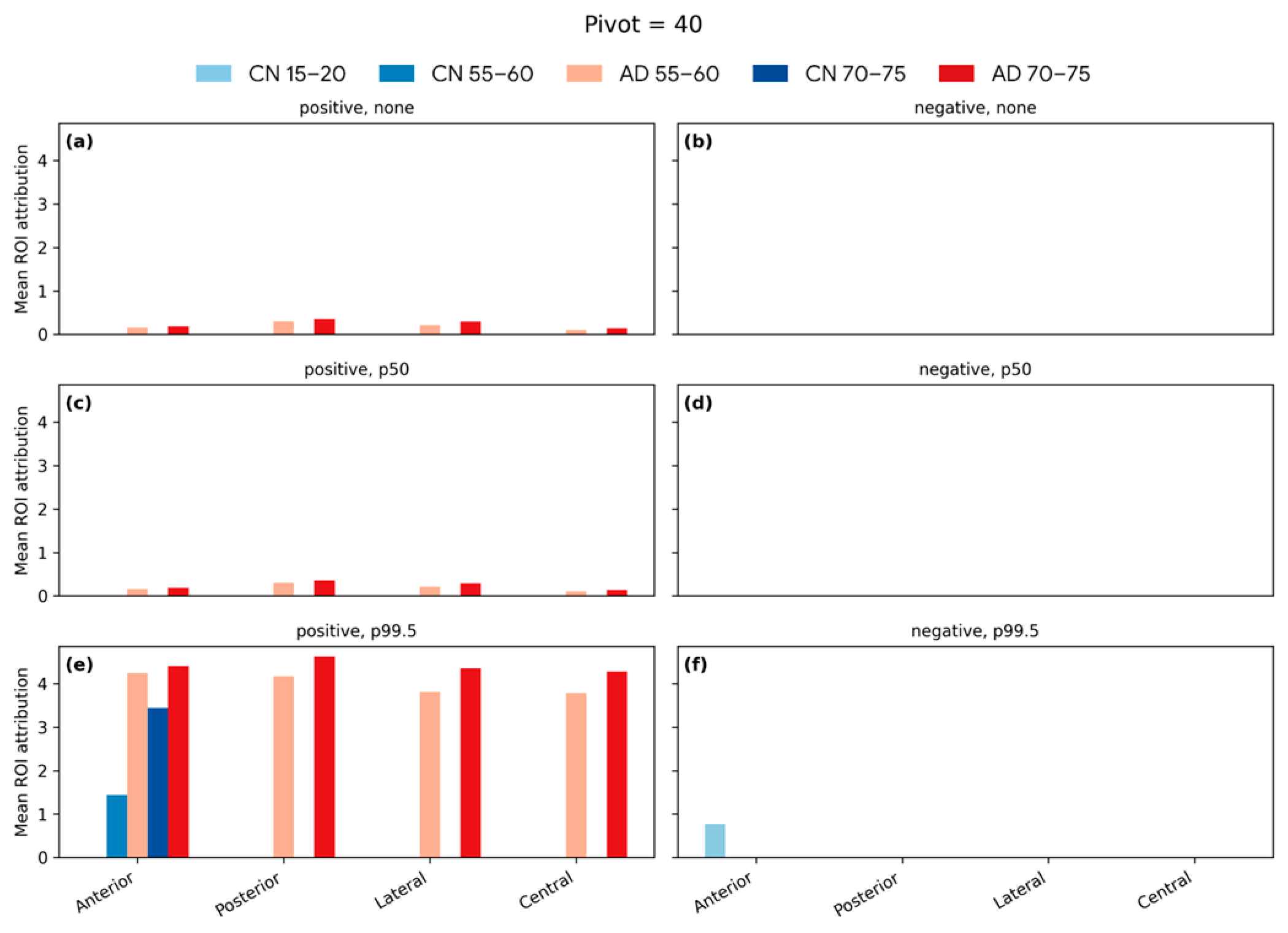

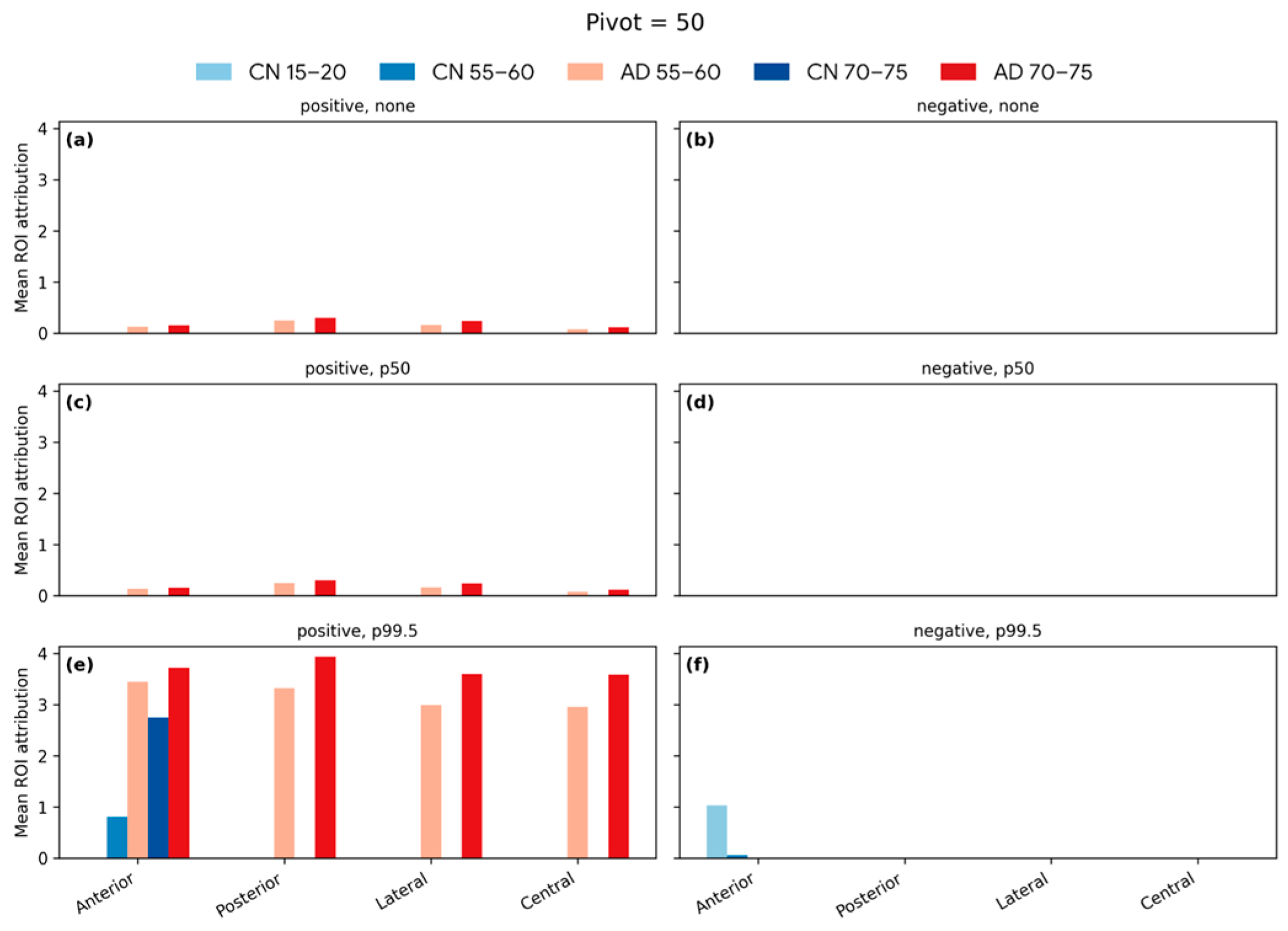

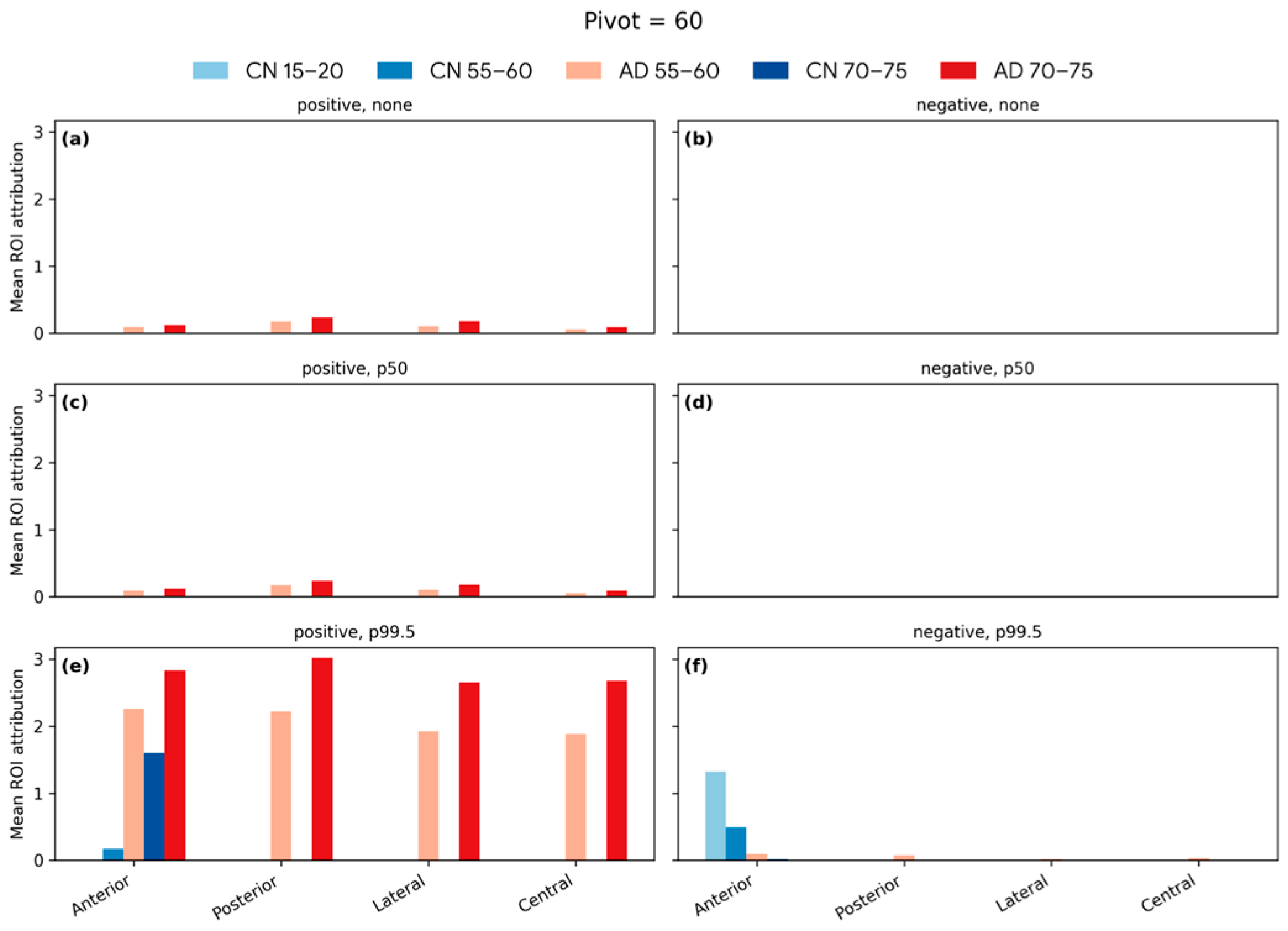

4.6. Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping Analysis

4.7. Limitations and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franke, K.; Luders, E.; May, A.; Wilke, M.; Gaser, C. Brain maturation: Predicting individual BrainAGE in children and adolescents using structural MRI. NeuroImage 2012, 63, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, B.A.; Bjornsdottir, G.; Thorgeirsson, T.E.; Ellingsen, L.M.; Walters, G.B.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Stefansson, H.; Stefansson, K.; Ulfarsson, M.O. Brain age prediction using deep learning uncovers associated sequence variants. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Kynast, J.; Beyer, F.; Masouleh, S.K.; Huntenburg, J.M.; Lampe, L.; Rahim, M.; Abraham, A.; Craddock, R.C.; et al. Predicting brain-age from multimodal imaging data captures cognitive impairment. NeuroImage 2017, 148, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.H.; Poudel, R.P.K.; Tsagkrasoulis, D.; Caan, M.W.A.; Steves, C.; Spector, T.D.; Montana, G. Predicting brain age with deep learning from raw imaging data results in a reliable and heritable biomarker. NeuroImage 2017, 163, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.A.; Kafiabadi, S.; Busaidi, A.A.; Guilhem, E.; Montvila, A.; Lynch, J.; Townend, M.; Agarwal, S.; Mazumder, A.; Barker, G.J.; et al. Accurate brain-age models for routine clinical MRI examinations. NeuroImage 2022, 249, 118871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springenberg, J.T.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T.; Riedmiller, M. Striving for Simplicity: The All Convolutional. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartora, C.; Marseglia, A.; Mårtensson, G.; Rukh, G.; Dang, J.; Muehlboeck, J.S.; Wahlund, L.O.; Moreno, R.; Barroso, J.; Ferreira, D.; et al. A deep learning model for brain age prediction using minimally preprocessed T1w images as input. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1303036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Knol, M.J.; Tiulpin, A.; Dubost, F.; de Bruijne, M.; Vernooij, M.W.; Adams, H.H.H.; Ikram, M.A.; Niessen, W.J.; Roshchupkin, G.V. Gray matter age prediction as a biomarker for risk of dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21213–21218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Gong, W.; Beckmann, C.F.; Vedaldi, A.; Smith, S.M. Accurate brain age prediction with lightweight deep neural networks. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 68, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Jia, X.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Dong, D.; Zeng, W. Multi-center brain age prediction via dual-modality fusion convolutional network. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 101, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltashani, F.; Parreno-Centeno, M.; Cole, J.H.; Papa, J.P.; Costen, F. Brain age prediction using a lightweight convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 6750–6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Zhao, H.; Liang, P. Brain age prediction based on brain region volume modeling under broad network field of view. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 265, 108739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Xia, Z.; Gao, X. Predicting brain age using Tri-UNet and various MRI scale features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Ding, J.; Ji, Q.; Jia, X.; Li, X.; Lee, Z.; et al. Brain age prediction using interpretable multi-feature-based convolutional neural network in mild traumatic brain injury. NeuroImage 2024, 297, 120751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xifra-Porxas, A.; Ghosh, A.; Mitsis, G.D.; Boudrias, M.-H. Estimating brain age from structural MRI and MEG data: Insights from dimensionality reduction techniques. NeuroImage 2021, 231, 117822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, J.L.; Lorenz, R.; Leech, R.; Cole, J.H. Bayesian optimization for neuroimaging pre-processing in brain age classification and prediction. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufumier, B.; Gori, P.; Battaglia, I.; Victor, J.; Grigis, A.; Duchesnay, E. Benchmarking CNN on 3D anatomical brain MRI: Architectures, data augmentation and deep ensemble learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.01132. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.L.; Adkins, D.J.; Bacas, E.; Zhou, P. Examining the reliability of brain age algorithms under varying degrees of participant motion. Brain Inform. 2024, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R.; Williams, N.; Cusack, R.; Auer, T.; Shafto, M.A.; Dixon, M.; Tyler, L.K.; Henson, R.N.; Consortium, C.-C.A. The Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience (Cam-CAN) data repository: Structural and functional MRI, MEG, and cognitive data from a cross-sectional adult lifespan sample. NeuroImage 2017, 144, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafto, M.A.; Tyler, L.K.; Dixon, M.; Taylor, J.R.; Rowe, J.B.; Cusack, R.; Calder, A.J.; Marslen-Wilson, W.D.; Duncan, J.; Dalgleish, T.; et al. The Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience (Cam-CAN) study protocol: A cross-sectional, lifespan, multidisciplinary examination of healthy cognitive ageing. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustison, N.J.; Cook, P.A.; Holbrook, A.J.; Johnson, H.J.; Muschelli, J.; Devenyi, G.A.; Duda, J.T.; Das, S.R.; Cullen, N.C.; Gillen, D.L.; et al. The ANTsX ecosystem for quantitative biological and medical imaging. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Shen, X.; Huang, J.; Ju, H.; Chen, Y.; Yin, T. Brain age prediction based on resting-state functional MRI using similarity metric convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57071–57082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1608.06993. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 839–847. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.; Beckmann, C.F.; Vedaldi, A.; Smith, S.M.; Peng, H. Optimising a simple fully convolutional network for accurate brain age prediction in the PAC 2019 challenge. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 627996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, S.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T. Regularizing brain age prediction via gated knowledge distillation. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. (PMLR) 2022, 172, 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Abdullah-Al-Wadud, M.; Al-Quaderi, G.D.; Shoyaib, M. An adaptive gamma correction for image enhancement. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2016, 2016, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky, S.J.; Willcox, B.J.; Demetrius, L.; Beltrán-Sánchez, H. Implausibility of radical life extension in humans in the twenty-first century. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautherot, M.; Kuchcinski, G.; Bordier, C.; Sillaire, A.R.; Delbeuck, X.; Leroy, M.; Leclerc, X.; Pruvo, J.-P.; Pasquier, F.; Lopes, R. Longitudinal analysis of brain-predicted age in amnestic and non-amnestic sporadic early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 729635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papouli, A.; Cole, J.H. Brain age prediction from MRI scans in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2025, 38, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, D.; Shu, N.; et al. Accelerated brain aging in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Relationships with individual cognitive decline, risk factors for Alzheimer disease, and clinical progression. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, e200171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestor, S.M.; Rupsingh, R.; Borrie, M.; Smith, M.; Accomazzi, V.; Wells, J.L.; Fogarty, J.; Bartha, R.; The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Ventricular enlargement as a possible measure of Alzheimer’s disease progression validated using the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Brain 2008, 131, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, H.; Goldman, A.L.; Sambataro, F.; Verchinski, B.A.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Weinberger, D.R.; Mattay, V.S. Normal age-related brain morphometric changes: Nonuniformity across cortical thickness, surface area and grey matter volume? Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 617.e1–617.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, S.; Patil, K.R.; Dahnke, R.; Hopkins, W.D.; Sherwood, C.C.; Caspers, S.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Hoffstaedter, F. The uniqueness of human vulnerability to brain aging in great ape evolution. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhovd, K.B.; Fjell, A.M.; Reinvang, I.; Lundervold, A.; Dale, A.; Eilertsen, D.E.; Quinn, B.T.; Salat, D.; Makris, N.; Fischl, B. Age-related changes in brain volumes across the adult lifespan and their relations to declarative memory: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, M.; Yang, J.; Gui, J.; Zhang, S. From Simple to Complex Scenes: Learning Robust Feature Representations for Accurate Human Parsing. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5449–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Xia, Z.; Ma, B.; Shi, Y.-Q. Light-Field Image Multiple Reversible Robust Watermarking Against Geometric Attacks. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 5861–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Articles | Dataset (n) | Training/Test (n) | Test Set Age Range (Years) | MAE (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | DeCODE (1469) a, IXI (440), UK biobank (12,395) | 1909/12,395 a | 45–80 | 3.63 |

| [3] | LIFE (2354) | 1177/1177 | 19–82 | 4.29 |

| [4] | BAHC (2001) b | 1601/200 | 18–90 | 4.16 |

| [11] | CamCAN (483) | - | 18–88 | 5.47 |

| [12] | ABIDE I (228), ABIDE II (505), BNU (328), Berlin (142), Cleveland Clinic (150), IXI (544), ADNI (219), Train-39 (135) | 1801/225 | 6–90 | 3.56 |

| [13] | Healthy Group (1182) c | 850/332 | 19–84 | 4.60 |

| [14] | CamCAN (651) | 521/130 | 18–89 | 7.46 |

| [15] | IXI (459), CoRR (266), OASIS (264) ABIDE I (258), ABIDE II (217), Local Centers (118) | 1464/118 | 18–94 | 3.08 |

| [6] | Local Hospital (19,807) | 15,146/4661 | 18–95 | 2.97 |

| [16] | CamCAN (613) | - | 18–88 | 4.88 |

| [9] | Rotterdam Study (8768) | 5865/550 | 46–96 | 4.45 |

| [17] | BAHC (2003) d, CamCAN (648) | - | 18–88 | 5.08 |

| Articles | Preprocessing Methods | Data Augmentations | Model Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | GM/WM segmentation, bias correction, skull stripping, rigid registration, Jacobian maps | Rotation of 0–40°, Translation of 10 voxels. | ResNet WB, Jacobian maps, GM and WM combination model (10-fold cross-validation). |

| [3] | Skull stripping, linear registration, filtering, nonlinear registration, mcflirt, GM/WM segmentation, bias correction, denoising | SVR + Random Forest Multimodal stacking model (connectivity matrix 197, connectivity matrix 444, cortical thickness, cortical surface area, subcortical volumes) | |

| [4] | GM segmentation, motion artifact removal, nonlinear registration, resampling include modulation, spatial smoothing | Rotation of 0–40°, Translation of 10 pixels. | CNN GM normalized volume map model |

| [11] | T1-MRI: GM/WM/CSF segmentation, skull stripping, linear registration, spatial normalization, bias correction rs-fMRI: Removal of initial volumes, slice-timing correction, motion correction, rigid-body registration, spatial normalization, Gaussian smoothing, denoising, temporal filtering | BrainDCNw Dual-modality (weighted rs-fMRI functional connectivity + weighted T1 brain volume) model. (10-fold cross-validation). | |

| [12] | Skull stripping, linear registration, GM segmentation, resample and align | Weighted MAE Loss (assign higher importance to samples from underrepresented age groups). | Lightweight CNN GM model. |

| [13] | Brain region segmentation, skull stripping, affine registration, volume normalization | RFBLSO Brain region normalized volume feature model. | |

| [14] | Bias correction, skull stripping, affine registration, spatial smoothing, spatial normalization | Tri-UNet WB model. | |

| [15] | GM/WM segmentation, skull stripping, linear registration | Rotation of 0–40°, Translation of 10 voxels. | VGG-13 WB, GM and WM combination model (10-fold cross-validation). |

| [6] | Cropping to the same size, intensity normalization e | DenseNet121 WB (non-skull-stripped) model. | |

| [16] | MRI: GM/WM/CSF segmentation, cortical segmentation, skull stripping, nonlinear registration, Z-score normalization MEG: Filtering, resampling, denoising, leakage correction, source localization, brain region segmentation | CCA+GPR MRI-MEG feature stacking model (10-fold cross-validation) | |

| [9] | GM/WM/CSF segmentation, nonlinear registration, spatial modulation | Single-subject longitudinal model (one subject with one or multiple MRI scans from different time). | CNN GM density map model. |

| [17] | GM/WM segmentation, smoothing, affine registration, nonlinear registration, spatial normalization, modulation, bias correction | SVR GMV and WMV combination model. |

| Samples | Average Age ± Standard Deviation | Age Range | Female (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE | 561 | 17.1 ± 7.7 | 6–56 | 17.6% |

| ADNI | 562 | 71.5 ± 7.2 | 51–90 | 59.4% |

| CamCAN | 653 | 54.8 ± 18.6 | 18–89 | 50.5% |

| IXI | 563 | 48.7 ± 16.5 | 20–86 | 55.6% |

| Layer Configuration | Input → Output (Channels) |

|---|---|

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 1 → 32 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 32 → 64 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 64 → 128 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 128 → 256 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 256 → 256 |

| Conv (1 × 1 × 1) → BN → Pool → ReLU | 256 → 64 |

| Global Average Pooling | - |

| Dropout | - |

| Conv (1 × 1 × 1) | 64 → 1 |

| Article | Model Architecture | Parameter Counts |

|---|---|---|

| Ours | Ours | 2,953,586 |

| [25] | ResNet-18 (3D) | 33,186,546 |

| [26] | DenseNet-121 (3D) | 11,293,874 |

| Layer Configuration | Input → Output (Channels) |

|---|---|

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 1 → 32 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 32 → 64 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 64 → 128 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 128 → 256 |

| Conv → BN → Pool → ReLU | 256 → 256 |

| Conv (1 × 1 × 1) → BN → Pool → ReLU | 256 → 64 |

| Global Average Pooling | - |

| Dropout | - |

| Conv (1 × 1 × 1) | 64 → 50 |

| Softmax | - |

| Weighted Sum | 50 → 1 |

| Output of the Softmax Layer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel | 1 | 2 | 3 | … | 48 | 49 | 50 |

| Age Class | 2 | 4 | 6 | … | 96 | 98 | 100 |

| Probability | p1 | p2 | p3 | … | p48 | p49 | p50 |

| Model | Optimizer | Dropout Rate | Training Set MAE | Test Set MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | SGD | 0 | 1.19 | 4.66 |

| Adam | 0 | 1.19 | 4.34 | |

| Adam | 0.2 | 1.42 | 4.38 | |

| Softmax | SGD | 0 | 1.13 | 4.43 |

| Adam | 0 | 1.12 | 4.38 | |

| Adam | 0.2 | 1.06 | 4.33 | |

| Adam | 0.5 | 1.26 | 4.35 |

| Test Set with Data Augmentation | Test Set Without Data Augmentation | |

|---|---|---|

| ABIDE | 2.85 | 2.77 |

| ADNI | 4.33 | 4.14 |

| CamCAN | 5.53 | 4.90 |

| IXI | 4.34 | 4.33 |

| Whole Test Set | 4.33 | 4.08 |

| Articles | Training/Test (Images) | Test Set Age Range (Years) | Test Set MAE (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 1871/468 | 6–90 | 4.08 |

| Ours | 1871/110 a | 6–56 | 2.77 |

| [12] | 1801/225 | 6–90 | 3.56 |

| [13] | 850/332 | 19–84 | 4.60 |

| [15] | 1464/118 | 18–94 | 3.08 |

| [6] | 15,146/4661 | 18–95 | 2.97 |

| [9] | 5865/550 | 46–96 | 4.45 |

| [2] | 1909/12,395 | 45–80 | 3.63 |

| [3] | 1177/1177 | 19–82 | 4.29 |

| [4] | 1601/200 | 18–90 | 4.16 |

| Model | Training/Test (n Images) | Test Set MAE (Years) |

|---|---|---|

| [11] | - | 5.47 |

| [14] | 521/130 | 7.46 |

| [16] (MRI + MEG) | - | 4.88 |

| [16] (MRI only) | - | 5.33 |

| [17] | 2003/648 | 5.08 |

| Ours | 1871/135 | 4.90 |

| Age Group | CN (Images) | AD (Images) |

|---|---|---|

| 15–20 | 34 | - |

| 55–65 | 27 | 15 |

| 70–75 | 56 | 116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chang, T.-A.; Yan, S.-Y.; Wang, K.-C.; Hung, C.-W. Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping: An Interpretable Visualization Framework for MRI-Based Brain Age Prediction. Electronics 2026, 15, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010220

Chang T-A, Yan S-Y, Wang K-C, Hung C-W. Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping: An Interpretable Visualization Framework for MRI-Based Brain Age Prediction. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010220

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ting-An, Shao-Yu Yan, Kuan-Chih Wang, and Chung-Wen Hung. 2026. "Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping: An Interpretable Visualization Framework for MRI-Based Brain Age Prediction" Electronics 15, no. 1: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010220

APA StyleChang, T.-A., Yan, S.-Y., Wang, K.-C., & Hung, C.-W. (2026). Softmax-Derived Brain Age Mapping: An Interpretable Visualization Framework for MRI-Based Brain Age Prediction. Electronics, 15(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010220