Mouse Data Defence Technology Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on the WM_INPUT Message

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This paper analyzes existing mouse data attack methods using machine learning, based on prior research and datasets used in these attacks, and proposes a GAN-based technology to protect mouse data. The proposed technology reduces the success rate of mouse data attacks, thereby ensuring the safer protection of user authentication information.

- The paper uses CTGAN (Conditional Tabular GAN), a type of GAN, to generate 2D data and analyzes the protection method for mouse data. This approach is novel and unique in the context of mouse data protection.

- In prior research, the maximum success rate of machine learning-based mouse data attacks was 99%. However, the defence technology proposed in this paper reduced the attack success rate by up to 37%. This means the attacker now only achieves a 63% success rate, and since mouse data involves continuous coordinates, if the attacker cannot capture consecutive coordinates, they cannot succeed in authenticating, thus enhancing security.

2. Related Research and Research Motivation

3. Proposed Technology and Dataset

3.1. Pre-Validation of the Proposed Technology

3.2. Structure of the Proposed Defence Technology

Dataset Configuration of Experiments

4. Experimental Results

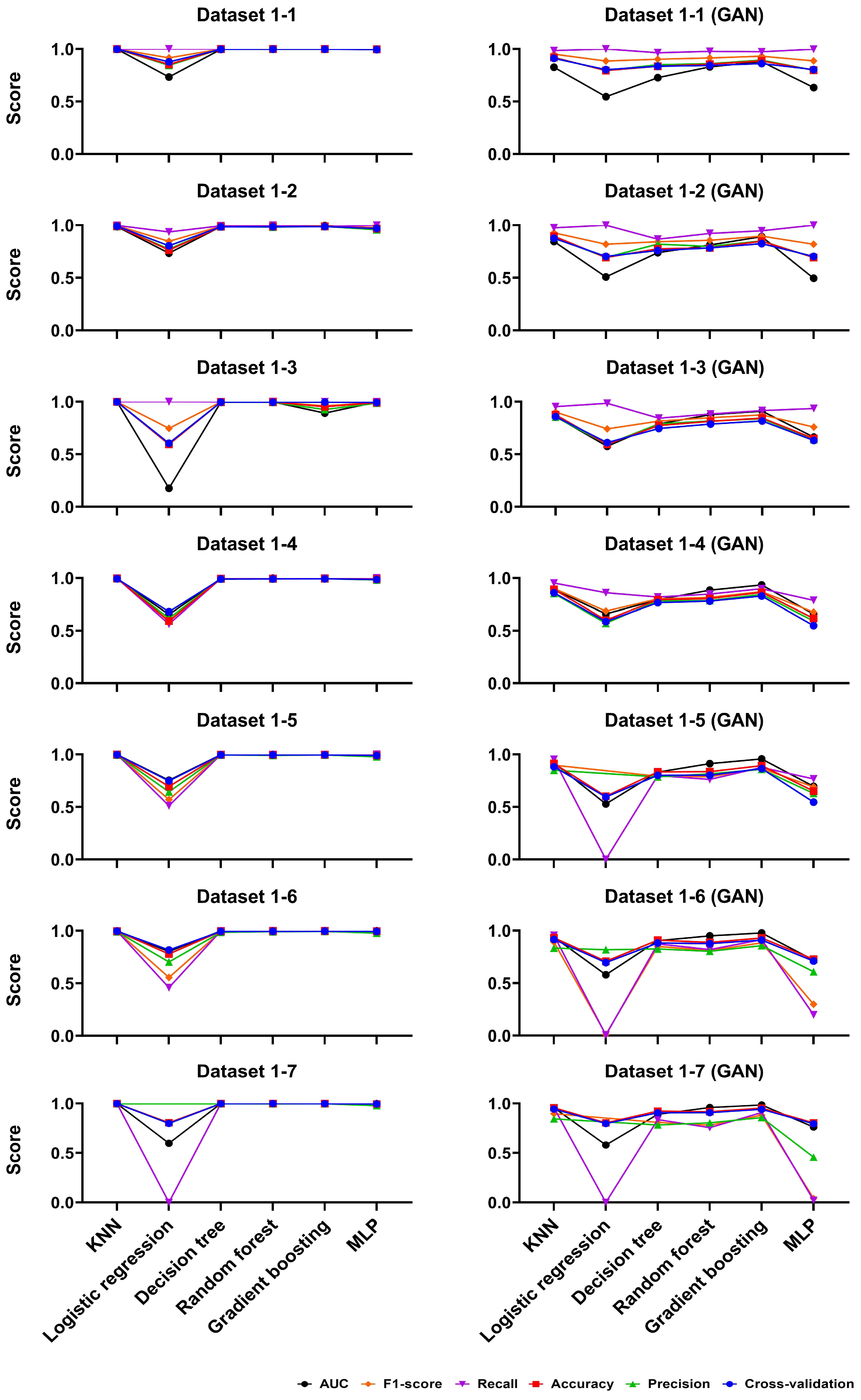

4.1. First Experiment Results of the Mouse Data Defence Technology

4.2. Second Experiment Results of the Mouse Data Defence Technology

4.3. Third Experiment Results of the Mouse Data Defence Technology

4.4. Overall Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Mouse Data Defence Technology According to Feature Sets and Datasets

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation Results Based on Performance Changes

5.2. Overall Performance Change Rate Analysis by Model for the Proposed Mouse Data Defence Technology

5.3. Discussion of the Use and Utilization of Synthetic Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NIA. Survey on the Internet Usage. Available online: https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=99870&bcIdx=26523&parentSeq=26523 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Baig, A.F.; Eskeland, S. Security, Privacy, and Usability in Continuous Authentication: A Survey. Sensors 2021, 21, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavya, C.; Suganya, R. Survey on keystroke logging attacks. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts (IJCRT) 2021, 9, 503–508. Available online: https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2104074.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- MSDN. WM_INPUT Message. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/inputdev/wm-input (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- MSDN. GetCursorPos Function (winuser.h). Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/ko-kr/windows/win32/api/winuser/nf-winuser-getcursorpos (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Quang, D.; Martini, B.; Raymond, C.K. The role of the adversary model in applied security research. Comput. Secur. 2019, 81, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.; Lee, K.; Yim, K. A Protection Technique for Screen Image-based Authentication Protocols Utilizing the SetCursorPos function. In Proceedings of the 18th International Workshop on Information Security Applications (WISA), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 24–26 August 2017; pp. 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- MSDN. SetCursorPos Function (winuser.h). Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/winuser/nf-winuser-setcursorpos (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Chong, P.; Elovici, Y.; Binder, A. User Authentication Based on Mouse Dynamics Using Deep Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Study. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 15, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S. Improved Practical Vulnerability Analysis of Mouse Data According to Offensive Security based on Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication. Entropy 2020, 22, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Ling, Z.; Pingley, A.; Yu, W.; Zhang, N.; Fu, X. How privacy leaks from bluetooth mouse? In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Raleigh, NC, USA, 16–18 October 2012; pp. 1013–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, M.; Egyed-Zsigmond, E. Intrusion Detection Using Mouse Dynamics. IET Biometrics 2019, 8, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Niu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y. An Insider Threat Detection Approach Based on Mouse Dynamics and Deep Learning. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 3898951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, S.; Assery, N.; Roy, K. An Empirical Evaluation of Online Continuous Authentication and Anomaly Detection Using Mouse Clickstream Data Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Hong, S.; Lee, K. Mouse Data Attack Technique Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on a Defense Technique Using the WM_INPUT Message. Electronics 2024, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulwahab, S.; Kim, Y.; Seo, A.; Son, Y. Generating Synthetic Dataset for ML-Based IDS Using CTGAN and Feature Selection to Protect Smart IoT Environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Figueira, A. On the Quality of Synthetic Generated Tabular Data. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgeldawi, E.; Sayed, A.; Galal, A.; Zaki, A.M. Hyperparameter Tuning for Machine Learning Algorithms Used for Arabic Sentiment Analysis. Informatics 2021, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Luo, Y.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, D. Exploring the Pedestrian Route Choice Behaviors by Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Geo-Inf. (ISPRS) 2024, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapaty, M.; Ray, A.; Padhy, N. A Decision Support System for Crop Recommendation Using Machine Learning Classification Algorithms. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelcenia, E.; Prakoonwit, S. Effective Feature Engineering and Classification of Breast Cancer Diagnosis: A Comparative Study. BioMedInformatics 2023, 3, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergni, L.; Todisco, F. A Random Forest Machine Learning Approach for the Identification and Quantification of Erosive Events. Water 2023, 15, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvanidi, A.; Katsoulas, N. Performance of Gradient Boosting Learning Algorithm for Crop Stress Identification in Greenhouse Cultivation. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Oviedo, A.; Ortega, N.; Orozco, E.; Gómez, A.; Londoño, J.M. Machine-Learning-Based Predictive Models for Compressive Strength, Flexural Strength, and Slump of Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, K.; Sallan, J.M. Study of Delay Prediction in the US Airport Network. Aerospace 2023, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Generation Period | Total Data | Real Mouse Data | Fake Mouse Data | Ratio (Real:Fake) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 50 ms | 20,000 | 16,003 | 3997 | 8:2 |

| 1-2 | 14,009 | 5991 | 7:3 | ||

| 1-3 | 12,005 | 7995 | 6:4 | ||

| 1-4 | 10,282 | 9718 | 5:5 | ||

| 1-5 | 8011 | 11,989 | 4:6 | ||

| 1-6 | 6000 | 14,000 | 3:7 | ||

| 1-7 | 4004 | 15,996 | 2:8 | ||

| 4-1 | 500 ms | 20,000 | 16,042 | 3958 | 8:2 |

| 4-2 | 14,080 | 5920 | 7:3 | ||

| 4-3 | 12,021 | 7979 | 6:4 | ||

| 4-4 | 10,009 | 9991 | 5:5 | ||

| 4-5 | 8319 | 11,681 | 4:6 | ||

| 4-6 | 6068 | 13,932 | 3:7 | ||

| 4-7 | 4049 | 15,951 | 2:8 |

| Model | Hyperparameters | Training Score | Validation Score | Test Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN (K-Nearest Neighbors) | n_neighbors = 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Logistic Regression | C = 1000, penalty = L2 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Decision Tree | max_depth = 13 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Random Forest | n_estimators = 10 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Gradient Boosting | max_depth = 15, learning_rate = 0.1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) | max_iter = 100, alpha = 1 × 10−5 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Performance | Generation Interval | Dataset | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Performance | 50 ms | 1-2 | MLP |

| 500 ms | 4-2 | Logistic Regression | |

| Lowest Performance | 50 ms | 1-3 | Logistic Regression |

| 500 ms | 4-6 | Gradient Boosting |

| Performance | Generation Interval | Dataset | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Performance | 50 ms | 1-6 | MLP |

| 500 ms | 4-2 | Logistic Regression | |

| Lowest Performance | 50 ms | 1-3 | Gradient Boosting |

| 500 ms | 4-4 | Gradient Boosting |

| Performance | Generation Interval | Dataset | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Performance | 50 ms | 1-6 | MLP |

| 500 ms | 4-2 | Logistic Regression | |

| Lowest Performance | 50 ms | 1-7 | Gradient Boosting |

| 500 ms | 4-6 | Gradient Boosting |

| Performance | Generation Interval | Experiment | Features | Dataset | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Performance | 50 ms | Third Experiment | Timestamp, X coordinate, Y coordinate, X distance, Y distance | 1-7 | Gradient Boosting |

| 500 ms | Third Experiment | Timestamp, X coordinate, Y coordinate, X distance, Y distance | 4-7 | Gradient Boosting | |

| Lowest Performance | 50 ms | Third Experiment | Timestamp, X coordinate, Y coordinate, X distance, Y distance | 1-5 | Logistic Regression |

| 500 ms | Third Experiment | Timestamp, X coordinate, Y coordinate, X distance, Y distance | 4-2 | Logistic Regression |

| Dataset/ Interval | Model | Data | AC | ± | P | ± | R | ± | F | ± | AU | ± |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-5/ 50 ms | KNN | D | 0.998 | −6% | 0.996 | −12% | 0.999 | −2% | 0.998 | −7% | 0.998 | −6% |

| GAN | 0.936 | 0.872 | 0.982 | 0.924 | 0.943 | |||||||

| Logistic Regression | D | 0.692 | −13% | 0.641 | - | 0.51 | - | 0.568 | - | 0.758 | −30% | |

| GAN | 0.601 | Nan | 0 | Nan | 0.532 | |||||||

| Decision Tree | D | 0.998 | −9% | 0.996 | −12% | 0.999 | −9% | 0.998 | −11% | 0.998 | −9% | |

| GAN | 0.912 | 0.874 | 0.911 | 0.892 | 0.912 | |||||||

| Random Forest | D | 0.998 | −6% | 0.996 | −8% | 0.999 | −7% | 0.998 | −8% | 0.999 | −2% | |

| GAN | 0.938 | 0.917 | 0.93 | 0.923 | 0.979 | |||||||

| Gradient Boosting | D | 0.999 | −4% | 0.996 | −7% | 1 | −4% | 0.998 | −5% | 0.999 | −1% | |

| GAN | 0.957 | 0.93 | 0.964 | 0.947 | 0.989 | |||||||

| MLP | D | 0.998 | −37% | 0.996 | −46% | 0.999 | −55% | 0.998 | −51% | 0.998 | −30% | |

| GAN | 0.629 | 0.542 | 0.452 | 0.493 | 0.697 | |||||||

| 1-7/ 50 ms | KNN | D | 0.999 | −3% | 0.998 | −13% | 0.999 | −2% | 0.998 | −8% | 0.999 | −3% |

| GAN | 0.966 | 0.846 | 0.98 | 0.918 | 0.971 | |||||||

| Logistic Regression | D | 0.806 | - | nan | - | 0 | - | nan | - | 0.597 | −2% | |

| GAN | 0.805 | nan | 0 | nan | 0.586 | |||||||

| Decision Tree | D | 1 | −4% | 1 | −13% | 1 | −10% | 1 | −11% | 1 | −6% | |

| GAN | 0.956 | 0.873 | 0.905 | 0.888 | 0.936 | |||||||

| Random Forest | D | 0.999 | −3% | 1 | −8% | 0.996 | −7% | 0.998 | −7% | 0.999 | −1% | |

| GAN | 0.971 | 0.919 | 0.931 | 0.925 | 0.992 | |||||||

| Gradient Boosting | D | 1 | −2% | 0.999 | −6% | 1 | −3% | 0.999 | −5% | 1 | - | |

| GAN | 0.98 | 0.935 | 0.966 | 0.95 | 0.995 | |||||||

| MLP | D | 0.997 | −19% | 0.989 | −40% | 0.997 | −89% | 0.993 | −81% | 0.999 | −19% | |

| GAN | 0.812 | 0.592 | 0.112 | 0.188 | 0.808 |

| Dataset/ Interval | Model | Data | AC | ± | P | ± | R | ± | F | ± | AU | ± |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-2/ 500 ms | KNN | D | 0.998 | −8% | 0.999 | −9% | 0.998 | −1% | 0.999 | −6% | 0.998 | −12% |

| GAN | 0.919 | 0.905 | 0.987 | 0.944 | 0.874 | |||||||

| Logistic Regression | D | 0.997 | −26% | 0.997 | −27% | 0.998 | - | 0.998 | −16% | 0.996 | −42% | |

| GAN | 0.734 | 0.724 | 0.999 | 0.84 | 0.581 | |||||||

| Decision Tree | D | 0.999 | −11% | 0.999 | −9% | 0.999 | −6% | 0.999 | −7% | 0.997 | −13% | |

| GAN | 0.89. | 0.908 | 0.941 | 0.925 | 0.867 | |||||||

| Random Forest | D | 0.998 | −9% | 0.998 | −10% | 0.999 | −2% | 0.999 | −6% | 0.999 | −5% | |

| GAN | 0.906 | 0.898 | 0.75 | 0.935 | 0.948 | |||||||

| Gradient Boosting | D | 0.998 | −7% | 0.999 | −8% | 0.999 | −2% | 0.999 | −5% | 0.999 | −3% | |

| GAN | 0.926 | 0.919 | 0.98 | 0.949 | 0.97 | |||||||

| MLP | D | 0.998 | −22% | 0.997 | −23% | 0.999 | −2% | 0.998 | −14% | 0.998 | −24% | |

| GAN | 0.783 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.863 | 0.758 | |||||||

| 4-7/ 500 ms | KNN | D | 0.999 | −3% | 0.997 | −13% | 0.998 | −3% | 0.998 | −8% | 0.998 | −3% |

| GAN | 0.965 | 0.87 | 0.969 | 0.917 | 0.966 | |||||||

| Logistic Regression | D | 0.997 | −20% | 0.987 | −58% | 0.997 | −97% | 0.992 | −94% | 0.998 | −3% | |

| GAN | 0.799 | 0.41 | 0.034 | 0.063 | 0.693 | |||||||

| Decision Tree | D | 0.999 | −4% | 0.999 | −12% | 0.998 | −8% | 0.999 | −10% | 0.998 | −5% | |

| GAN | 0.958 | 0.879 | 0.916 | 0.897 | 0.946 | |||||||

| Random Forest | D | 0.999 | −3% | 0.998 | −7% | 0.999 | −6% | 0.999 | −7% | 0.999 | −1% | |

| GAN | 0.973 | 0.926 | 0.941 | 0.933 | 0.993 | |||||||

| Gradient Boosting | D | 0.999 | −2% | 0.998 | −5% | 0.999 | −4% | 0.999 | −5% | 0.999 | - | |

| GAN | 0.981 | 0.946 | 0.958 | 0.952 | 0.996 | |||||||

| MLP | D | 0.997 | −14% | 0.987 | −26% | 0.997 | −52% | 0.992 | −42% | 0.998 | −9% | |

| GAN | 0.862 | 0.734 | 0.478 | 0.579 | 0.904 |

| Dataset | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-5 | −37% | −46% | −55% | −51% | −30% | MLP |

| 1-7 | −19% | −40% | −89% | −81% | −19% | MLP |

| 4-2 | −26% | −27% | − | −16% | −42% | Logistic Regression |

| 4-7 | −20% | −58% | −97% | −94% | −31% | Logistic Regression |

| 50 ms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | t-Statistic | Confidence Interval (95%) | p-Value (One-Tailed) |

| F1 | 3.978 | 0.049~0.226 | 5.278 × 10−3 |

| F2 | 4.541 | 0.077~0.277 | 3.081 × 10−3 |

| F3 | 2.907 | 0.011~0.184 | 1.675 × 10−2 |

| 500 ms | |||

| Feature | t-Statistic | Confidence Interval (95%) | p-Value (One-Tailed) |

| F1 | 3.825 | 0.043~0.217 | 6.154 × 10−3 |

| F2 | 10.350 | 0.142~0.236 | 7.247 × 10−5 |

| F3 | 2.984 | 0.015~0.203 | 1.532 × 10−2 |

| 50 ms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | KL(Genuine || GAN) | KL (GAN || Genuine) | JS Divergence |

| TIME | 1.008621 | 12.555358 | 0.242797 |

| X | 0.175021 | 1.415825 | 0.048420 |

| Y | 0.586104 | 2.276023 | 0.132121 |

| DIFFPOSX | 0.011696 | 0.045298 | 0.003040 |

| DIFFPOSY | 0.028258 | 0.068322 | 0.006867 |

| 500 ms | |||

| Feature | KL(Genuine || GAN) | KL (GAN || Genuine) | JS Divergence |

| TIME | 0.804133 | 9.186281 | 0.214075 |

| X | 0.289566 | 1.075720 | 0.073465 |

| Y | 0.283905 | 1.347653 | 0.068019 |

| DIFFPOSX | 0.007561 | 0.026126 | 0.001935 |

| DIFFPOSY | 0.030696 | 0.069390 | 0.007558 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jung, W.; Kim, J.; Lee, K. Mouse Data Defence Technology Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on the WM_INPUT Message. Electronics 2026, 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010016

Jung W, Kim J, Lee K. Mouse Data Defence Technology Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on the WM_INPUT Message. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Wontae, Jinwook Kim, and Kyungroul Lee. 2026. "Mouse Data Defence Technology Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on the WM_INPUT Message" Electronics 15, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010016

APA StyleJung, W., Kim, J., & Lee, K. (2026). Mouse Data Defence Technology Using Machine Learning in Image-Based User Authentication: Based on the WM_INPUT Message. Electronics, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010016