Simultaneously Captures Node-Level and Sequence-Level Features in Parallel for Cascade Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Loose requirements for data: Traditional cascade prediction methods often require a lot of data sets to achieve decent prediction results, and have very strict requirements for datasets. For example, CasCN [4] requires that the training and prediction data sets must be cascade graphs with no more than 100 cascades within the observation time. DeepHawkes [3] needs to introduce time parameters in order to greatly improve the performance of the model compared with DeepCas [2] and other traditional cascade prediction models. However, the model we proposed in this paper only needs a small amount of training data and the datasets do not need time parameters for training a good performance model.

- Accurately capturing local and global features of nodes: Traditional cascade prediction methods simply use recurrent neural networks or graph convolutional neural networks, which can only capture the embedding relationship between nodes and their adjacent nodes, and cannot directly capture the embedding relationship between nodes and all nodes in the sequence. The proposed cascade prediction framework introduces a Transformer, which can capture the embedding relationship between each node in the sequence and all other nodes in the sequence.

- Accurately capturing the multi-dimensional features of nodes: Traditional cascade prediction frameworks, such as DeepCas [2], and Deephawkes [3], obtain the embedding of the entire sequence by summing weighted sequence nodes, and the weight parameters are difficult to learn. The proposed cascade prediction framework introduces a dynamic routing algorithm to directly capture the multi-dimensional embedding of the entire sequence, and it makes the obtained sequence embedding more usable.

2. Related Work

2.1. Cascade Prediction

2.1.1. Methods Based on Random Point Process

2.1.2. Methods Based on Feature Engineering

2.1.3. Methods Based on Deep Learning

2.2. Multi-Head Self-Attention Mechanism

2.3. Dynamic Routing Mechanism

3. Method

3.1. Relevant Definition

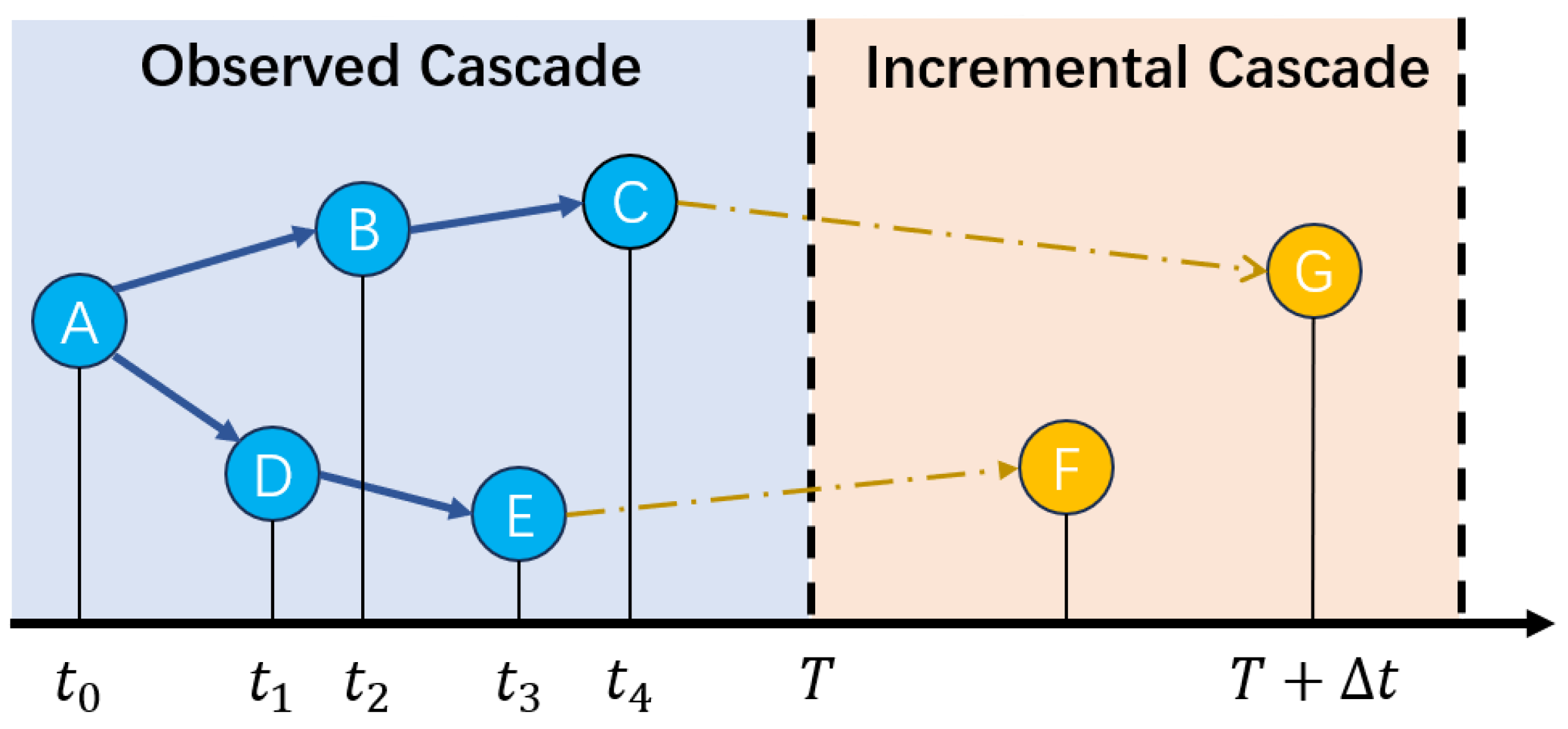

- Cascade Graph: Suppose we have a total of M message propagation paths, denoted as . For each message , we use a cascade graph to record the diffusion process of message , where is a subset of nodes in V, and is the set of edges, as shown in Figure 2. A node in represents a cascade participant, such as a citation relationship in a paper citation network or a user involved in message reposting in a social network. An edge represents an interaction between nodes u and v.

- Cascade Prediction: Given the information propagation processes and paths within the observation time window [0, T), our objective is to predict the incremental popularity between the observed popularity and the final popularity of each cascade graph . This represents the popularity of the information beyond the observation time. To avoid the inherent correlation between the final popularity and the observed popularity, we choose to predict the incremental popularity,

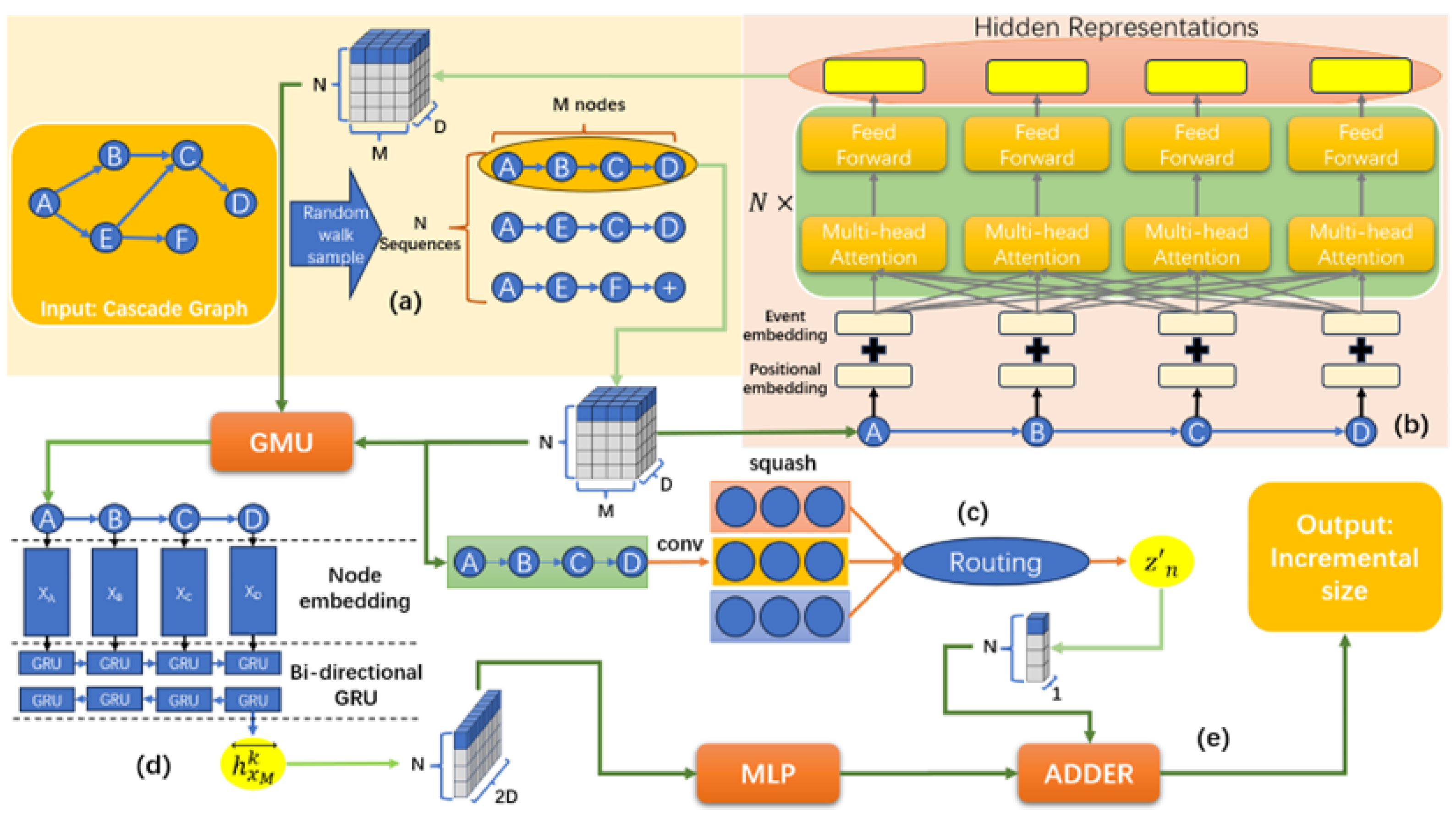

3.2. Proposed Model

- Embedding Initialization: Traverse the cascade graphs observed within the observed time, convert them into sequences, and transform the nodes in the sequences into vectors of predefined dimensions.

- Learning micro-level features between nodes: By leveraging the inter-node self-attention mechanism, we capture the hidden features of the target node and all other nodes in the sequence at a micro-level. This allows us to update the embedding of the target node.

- Learning meso-level features in a sequence: By utilizing multiple parallel one-dimensional convolutional layers, we obtain sequence-wide features from different dimensions at a meso-level. We then use the dynamic routing algorithm to aggregate weighted sums of sequence features from different dimensions, thereby updating the sequence features.

- Path Encoding and Sum Pooling: Use GRU to extract the embedding relationship features between nodes in the sequence and their neighboring nodes, and sum them to obtain the features of the entire cascading graph.

- Prediction Module: Utilize dense fully connected layers to output the predicted cascade size .

3.3. Embedding Initialization

3.4. Learning Meso-Level Features in a Sequence

3.4.1. Positional Encoder

3.4.2. Multi-Head Attention

3.4.3. Position-Wise Feed-Forward Networks

3.4.4. Compression Encoder

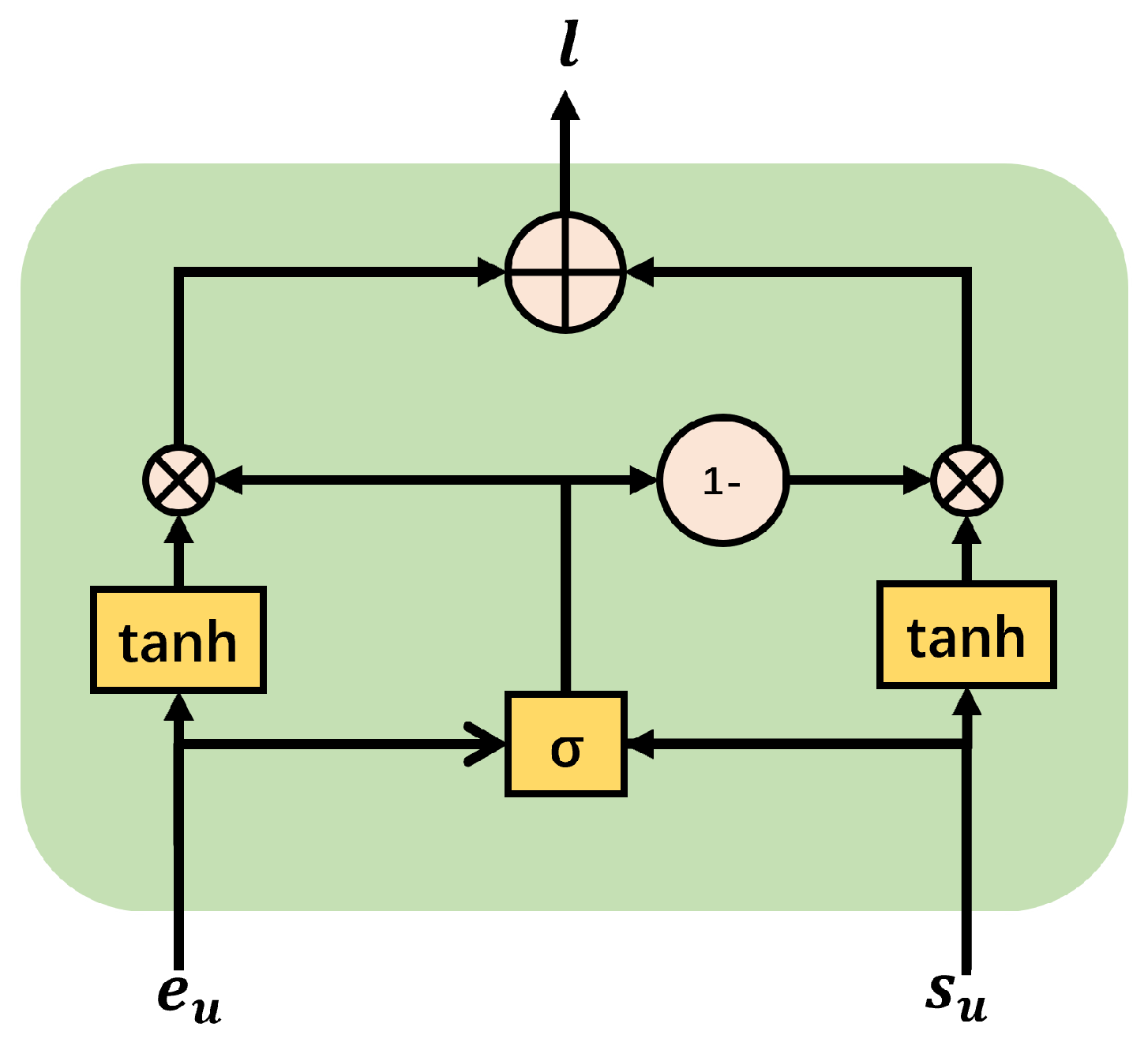

3.4.5. Gated Multi-Modal Units

3.5. Learning Micro-Level Features Between Nodes

| Algorithm 1: Dynamic Routing Process |

|

3.6. Path Encoding and Sum Pooling

3.7. Prediction Module

3.8. Framework Operational Mechanism

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Baseline Methods

4.3. Experimental Setup

4.4. Performance Comparison

4.5. Ablation Study

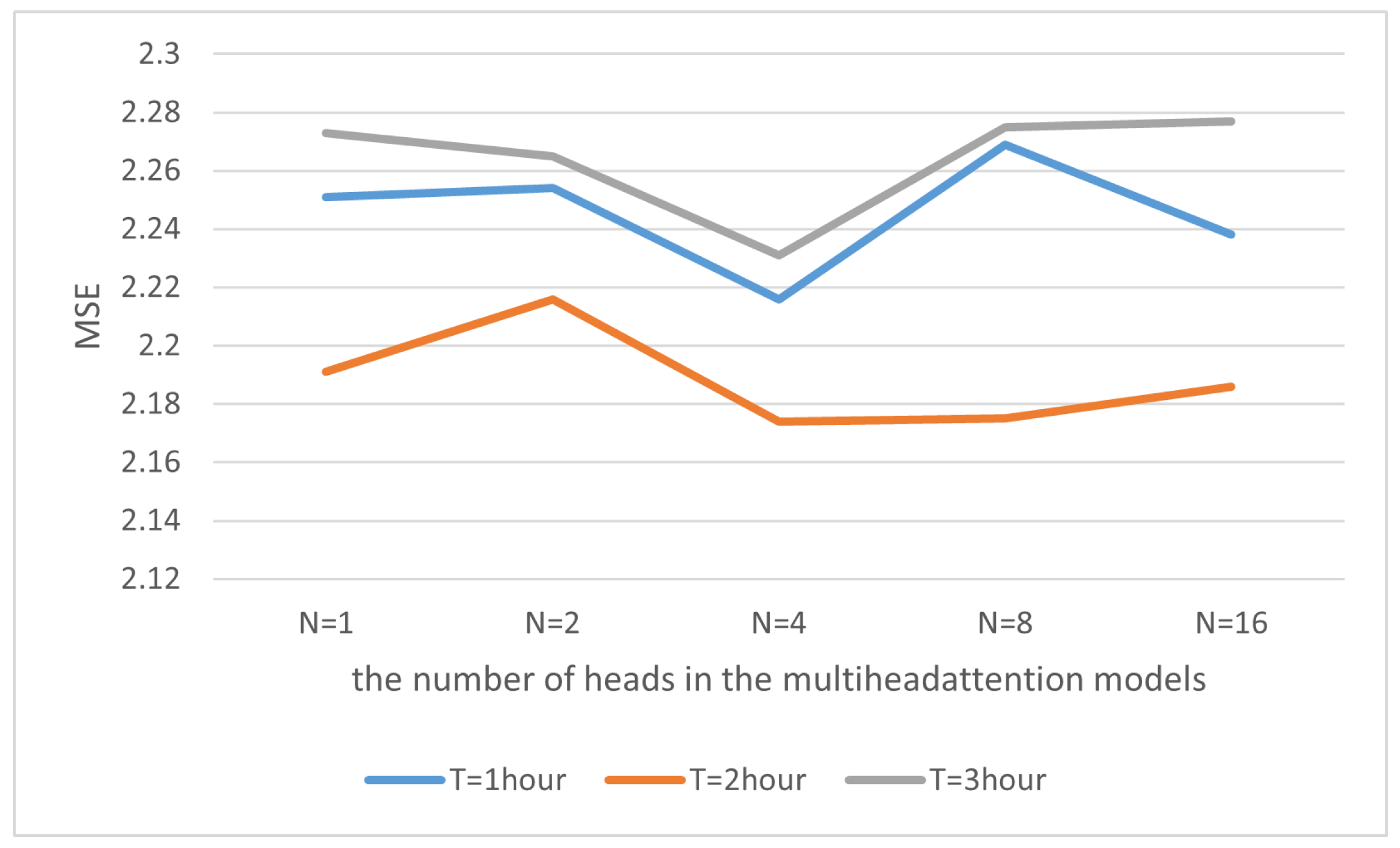

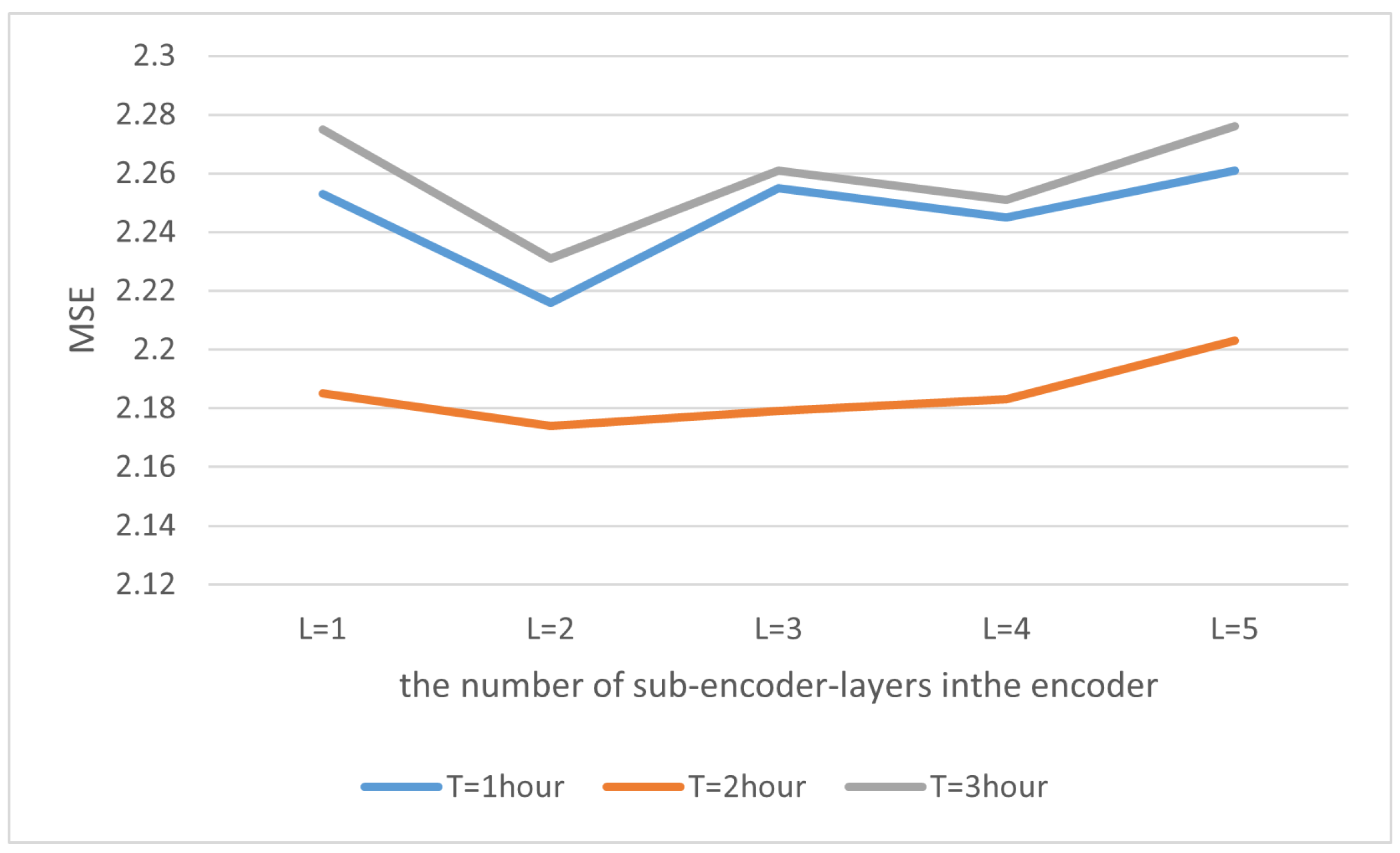

4.6. Analysis of Sensitivity to Hyper-Parameters

4.6.1. The Number of Heads in the Multi-Head Attention Models

4.6.2. The Number of Sub-Encoder-Layers in the Encoder

4.7. Computational Complexity and Scalability

5. Conclusions

Practical Implications and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouarara, H.A. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to Analyse Mental Behaviour in Social Media. Int. J. Softw. Sci. Comput. Intell. 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, J.; Guo, X.; Mei, Q. DeepCas: An End-to-end Predictor of Information Cascades. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’17), Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Shen, H.; Cen, K.; Ouyang, W.; Cheng, X. DeepHawkes: Bridging the Gap between Prediction and Understanding of Information Cascades. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM ’17), Singapore, 6–10 November 2017; pp. 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, K.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, F. Information Diffusion Prediction via Recurrent Cascades Convolution. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 35th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Macao, China, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Bao, P.; Yan, R.; Li, J.; Li, X. A Graph Temporal Information Learning Framework for Popularity Prediction. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022 (WWW ’22), Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wang, D.; Song, C.; Barabási, A. Modeling and Predicting Popularity Dynamics via Reinforced Poisson Processes. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Québec City, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, T.; Zang, C.; Cui, P.; Song, C.; Zhu, W. Collective Human Behavior in Cascading System: Discovery, Modeling and Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Singapore, 17–20 November 2018; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, S.; Chan, K.S.; Swami, A.; Korniss, G.; Szymanski, B.K. Information Cascades in Feed-Based Networks of Users with Limited Attention. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2017, 4, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, Z.; Yi, L.; K.S., N.; Qu, H.; Ma, X. WeSeer: Visual Analysis for Better Information Cascade Prediction of WeChat Articles. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Rizoiu, M.A.; Xie, L. Modeling Information Cascades with Self-exciting Processes via Generalized Epidemic Models. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM ’20), Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zheng, T. Pattern dynamics analysis and application of west nile virus spatiotemporal models based on higher-order network topology. Bull. Math. Biol. 2025, 87, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ding, Y.; Shen, S. Green behavior propagation analysis based on statistical theory and intelligent algorithm in data-driven environment. Math. Biosci. 2025, 379, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hu, B.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y. A group behavior prediction model based on sparse representation and complex message interactions. Inf. Sci. 2022, 601, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, M. Users’ mobility enhances information diffusion in online social networks. Inf. Sci. 2021, 546, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Chan, J.; Chen, L.; Sellis, T.; Zhang, Y. Event Popularity Prediction Using Influential Hashtags From Social Media. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 4797–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, J. User behavior prediction via heterogeneous information in social networks. Inf. Sci. 2021, 581, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Feature Generalization Framework for Social Media Popularity Prediction. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’20), Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 4570–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alweshah, M.; Khalaileh, S.A.; Gupta, B.B.; Almomani, A.; Hammouri, A.I.; Al-betar, M.A. The monarch butterfly optimization algorithm for solving feature selection problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 34, 11267–11281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, Y.; Neves, L.; Woodford, O.; Jiang, M.; Shah, N. Data augmentation for graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 11015–11023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, X. Time sensitivity-based popularity prediction for online promotion on Twitter. Inf. Sci. 2020, 525, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, S.M.; Podda, A.S.; Recupero, D.R.; Saia, R.; Usai, G. Popularity Prediction of Instagram Posts. Information 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Huang, W.; Liu, W.; Li, J. Popularity Prediction on Online Articles with Deep Fusion of Temporal Process and Content Features. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, D.; Xiong, F. Information cascades prediction with attention neural network. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, D.; Peng, Z.J.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. RNe2Vec: Information diffusion popularity prediction based on repost network embedding. Computing 2020, 103, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Li, Q.; Ma, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, A.; Chen, H. Knowledge-based Temporal Fusion Network for Interpretable Online Video Popularity Prediction. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022 (WWW ’22), Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, J.; Shi, P.; Deng, W.; Wang, H. Multimodal Deep Learning for Social Media Popularity Prediction with Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’20), Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 4580–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, B.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Yu, Z. App Popularity Prediction by Incorporating Time-Varying Hierarchical Interactions. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2022, 21, 1566–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Le, Q.V.; Salakhutdinov, R. Transformer-XL: Attentive Language Models Beyond a Fixed-Length Context. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.02860. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, M.; Smola, A.J. Language Models with Transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zuo, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, T.; Zha, H. Transformer Hawkes Process. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; Volume 119, pp. 11692–11702. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.07436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabour, S.; Frosst, N.; Hinton, G.E. Dynamic routing between capsules. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3859–3869. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasekara, H.; Jayasundara, V.; Athif, M.; Rajasegaran, J.; Jayasekara, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Rodrigo, R. TimeCaps: Capturing Time Series Data With Capsule Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:1911.11800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalwagy, A.; Kalganova, T. Multi-Channel LSTM-Capsule Autoencoder Network for Anomaly Detection on Multivariate Data. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; He, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; Ye, Y. GCRec: Graph-Augmented Capsule Network for Next-Item Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 10164–10177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, T.; Minervini, P.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. Convolutional 2D Knowledge Graph Embeddings. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1707.01476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Menczer, F.; Ahn, Y.Y. Virality Prediction and Community Structure in Social Networks. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, G.; Huberman, B.A. Predicting the popularity of online content. Commun. ACM 2010, 53, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.A. Association for computing machinery (ACM). In Encyclopedia of Computer Science; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, K.; Liu, S.; Trajcevski, G. CasFlow: Exploring Hierarchical Structures and Propagation Uncertainty for Cascade Prediction. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 3484–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Xiong, F.; Pan, S.; Wang, L.; Xiong, X. Hierarchical attention neural network for information cascade prediction. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Sina Weibo | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Cascades and Nodes in Different Observation Settings | ||

| Train (1 h/1 day) | 831 | 9639 |

| Val (1 h/1 day) | 178 | 2066 |

| Test (1 h/1 day) | 178 | 2066 |

| Nodes in | 56,065 | 271,792 |

| Train (2 h/2 day) | 908 | 12,739 |

| Val (2 h/2 day) | 194 | 2730 |

| Test (2 h/2 day) | 194 | 2730 |

| Nodes in | 66,422 | 370,947 |

| Train (3 h) | 927 | |

| Val (3 h) | 198 | |

| Test (3 h) | 198 | |

| Nodes in | 70,516 | |

| Model | Sina Weibo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Time | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 1 day | 2 day | |||||

| MSE | MAPE | MSE | MAPE | MSE | MAPE | MSE | MAPE | MSE | MAPE | |

| Feature-Linear | 3.655 | 0.322 | 3.211 | 0.276 | 3.123 | 0.271 | 9.326 | 0.520 | 6.758 | 0.459 |

| DeepCas | 3.468 | 0.311 | 2.899 | 0.256 | 2.698 | 0.233 | 7.438 | 0.485 | 6.357 | 0.500 |

| DeepHawkes | 3.338 | 0.306 | 2.721 | 0.241 | 2.392 | 0.211 | 7.216 | 0.587 | 5.788 | 0.536 |

| CasCN | 2.976 | 0.266 | 2.643 | 0.232 | 2.376 | 7.183 | 0.547 | 5.561 | 0.525 | |

| GTGCN | 2.421 | 0.227 | 2.378 | 2.322 | 0.215 | 6.988 | 0.472 | 5.172 | 0.377 | |

| CasFLow | 2.289 | 0.212 | 2.198 | 0.222 | 2.278 | 0.234 | 6.954 | 0.455 | 5.143 | 0.361 |

| CasHAN | 2.287 | 0.211 | 2.193 | 0.221 | 2.275 | 0.272 | 6.999 | 0.459 | 5.132 | 0.356 |

| CasNS-node | 2.419 | 0.221 | 2.210 | 0.220 | 2.318 | 0.239 | 6.977 | 0.452 | 5.134 | 0.362 |

| CasNS-sequence | 2.491 | 0.226 | 2.326 | 0.221 | 2.351 | 0.242 | 6.982 | 0.442 | 5.156 | 0.353 |

| CasNS | 0.223 | 0.249 | ||||||||

| Model | Training Time/Epoch (Minutes) | Inference Latency/Cascade (ms) | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepCas | ∼12 min | ∼7 ms | 0.893 |

| Our Model | ∼40 min | ∼24 ms | 0.928 () |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luo, G.; Zhao, N.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y. Simultaneously Captures Node-Level and Sequence-Level Features in Parallel for Cascade Prediction. Electronics 2026, 15, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010159

Luo G, Zhao N, Chen X, Gao Y. Simultaneously Captures Node-Level and Sequence-Level Features in Parallel for Cascade Prediction. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010159

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Guorong, Nan Zhao, Xiaoyu Chen, and Yi Gao. 2026. "Simultaneously Captures Node-Level and Sequence-Level Features in Parallel for Cascade Prediction" Electronics 15, no. 1: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010159

APA StyleLuo, G., Zhao, N., Chen, X., & Gao, Y. (2026). Simultaneously Captures Node-Level and Sequence-Level Features in Parallel for Cascade Prediction. Electronics, 15(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010159