Intelligent Routing Optimization via GCN-Transformer Hybrid Encoder and Reinforcement Learning in Space–Air–Ground Integrated Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Vision and Driving Forces of the Integrated Air Space Network (SAGIN)

1.2. Core Challenges of SAGIN Routing: High Dynamics and Strong Heterogeneity

1.3. Core Challenges of SAGIN Routing

- (1)

- Failure of OSPF (Open Shortest Path First): In LEO networks, the high-speed movement of satellites transforms topology changes from “occasional events” into “the norm,” continuously triggering Link State Advertisement (LSA) floods from OSPF nodes. Existing research indicates that as node scale expands, both LSA volume and routing overhead increase exponentially. Maintaining topology synchronization alone may consume over 12% of onboard bandwidth [14]. More critically, while control messages are still propagating through the network, the next wave of link switches arrives: routing tables are marked “outdated” before they can converge, triggering periodic oscillations, loops, and severe performance degradation [9].

- (2)

- Lag of BGP (Border Gateway Protocol): BGP’s distributed path discovery mechanism reveals critical shortcomings in highly dynamic inter-satellite topologies. Whenever a link switch occurs, BGP must undergo a lengthy cycle of “path discovery–revocation–rediscovery,” with convergence times often reaching tens of seconds or even minutes. During this period, the data plane is forced to adopt suboptimal or invalid routes, causing prolonged connection interruptions and high latency. For SAGIN real-time services demanding end-to-end latency below a low threshold, this “disconnect-then-reconnect” behavior is clearly unacceptable [15].

- (3)

- In addition to high dynamics and strong heterogeneity, centralized routing schemes also face non-negligible overhead challenges. The bandwidth resources of satellite networks are scarce (especially for satellite-ground links), and the uplink and downlink transmission delays are non-negligible. The processes such as state data interaction and routing rule issuance between the Centralized Control Center (G-CCC) and satellites, UAVs, and ground nodes will generate communication overhead. At the same time, the spatiotemporal prediction and reinforcement learning decision-making of G-CCC will generate computational overhead. If these overheads are not reasonably controlled, they may occupy a large amount of satellite bandwidth or prolong the uplink and downlink response time, making the centralized scheme infeasible. It has been confirmed that the LSA flooding of traditional protocols (such as OSPF) will consume more than 12% of the onboard bandwidth [14], while existing intelligent routing schemes (such as DQN and DDPG) have not been specially optimized for the overhead of centralized architectures, which is also a key issue that needs to be supplemented and is discussed in this paper.

1.4. Evolution of Intelligent Routing: From Q-Routing to DRL

- (1)

- Phase 1: Classical reinforcement learning (Q-Routing): Early Q-Routing introduced distributed reinforcement learning into the network layer, enabling each node to maintain a Q-value table so that packets “learn” optimal paths while being forwarded [18]. However, this tabular storage faced a dimensionality disaster in SAGIN, where node scale and state space expanded dramatically—Q-table size grew exponentially with the number of states and actions. Experiments show that when satellite counts exceed dozens, algorithm convergence time extends from seconds to minutes, with near-complete loss of generalization capability for unseen topologies [19]. Consequently, Q-Routing remains limited to small-scale static scenarios and cannot adapt to highly dynamic, large-scale air–ground–space networks.

- (2)

- Phase 2: Deep reinforcement learning (DRL): To overcome the dimensionality catastrophe, deep reinforcement learning replaces Q-tables with deep neural networks, achieving end-to-end abstraction of high-dimensional states. DQN pioneered the integration of convolutional networks with Q-learning, enabling direct action value outputs on continuous vectors like delay and queue length [12,20,21,22]. Policy gradient methods such as PPO and A2C further enhanced training stability and sample efficiency by constraining step size and advantage estimation [23,24]. Nevertheless, existing DRL routing still follows the passive “perception–action” paradigm: agents make decisions based solely on instantaneous features like current queue and link delay. They cannot predict satellite handover 10 min in advance or reserve bandwidth for sudden traffic surges, thus failing to exploit potential gains from SAGIN’s orbital periodicity and traffic predictability [25,26].

1.5. Contributions of This Paper: Deep Reinforcement Learning Based on Spatiotemporal Prediction

- (1)

- Spatiotemporal state prediction: The network state of SAGIN (latency, bandwidth, load) is essentially high-dimensional spatiotemporal graph data. To achieve proactive perception of network status, some studies treat SAGIN’s latency, bandwidth, and load as high-dimensional spatiotemporal graph signals and propose a “GCN-Transformer” hybrid encoder: first, a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) aggregates multi-hop neighbor features on the topological snapshot at each time step, extracting the spatial coupling relationships between satellite–satellite and satellite–ground links [30,31,32,33,34]; subsequently, the node embedding sequence output by the GCN is fed into the Transformer encoder, which captures the dynamic evolution of traffic and link quality over extended time spans through multi-head self-attention [35,36]. The two components are end-to-end concatenated to predict the entire network state for the next K time steps in a single pass, providing reliable “preview” input for subsequent routing decisions [27,34,37].

- (2)

- Hyperparameter optimization (PSO): For such a complex hybrid encoder, its hyperparameters (e.g., number of GCN layers, number of Transformer heads) are difficult to tune manually. This paper innovatively introduces the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to automatically search for the optimal hyperparameter combination with the goal of minimizing the prediction Mean Squared Error (MSE), avoiding local optima.

- (3)

- Intelligent routing decision (PPO): Some studies deploy Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) agents within the Ground Centralized Control Center (G-CCC), introducing “predict-then-decide” as a core innovation: the input to the Actor–Critic network is no longer the current instantaneous state but rather the future K-step network profile generated by the GCN-Transformer. This enables policy updates based on impending topological and traffic changes. To further compress the high-dimensional state space, the Actor network incorporates a spatiotemporal attention module: in the spatial dimension, it automatically focuses on predicting congested nodes and high-SNR links; in the temporal dimension, it prioritizes upcoming load peak windows. This enables a single output of forward-looking end-to-end routing policies, achieving simultaneous improvements in QoS and network utilization [38,39,40,41].

- (4)

- Summary of Contributions: This paper proposes a GCN-Transformer hybrid encoder to achieve high-precision spatiotemporal prediction of SAGIN network states. By introducing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for automatic search of encoder hyperparameters, prediction errors are significantly reduced. Building upon this, a PPO-based routing agent is designed, driven by “predicted information + spatiotemporal attention” to make forward-looking QoS decisions. Finally, leveraging real-world datasets from CelesTrak, CAIDA, and CRAWDAD, we establish a parameterized experimental platform. Through comparative, ablation, scalability, and robustness experiments, we validate that our proposed solution outperforms OSPF, Q-Routing, and standard DQN-Routing algorithms [21,23,24], offering a novel intelligent routing paradigm for integrated air–ground networks.

2. Problem Modeling

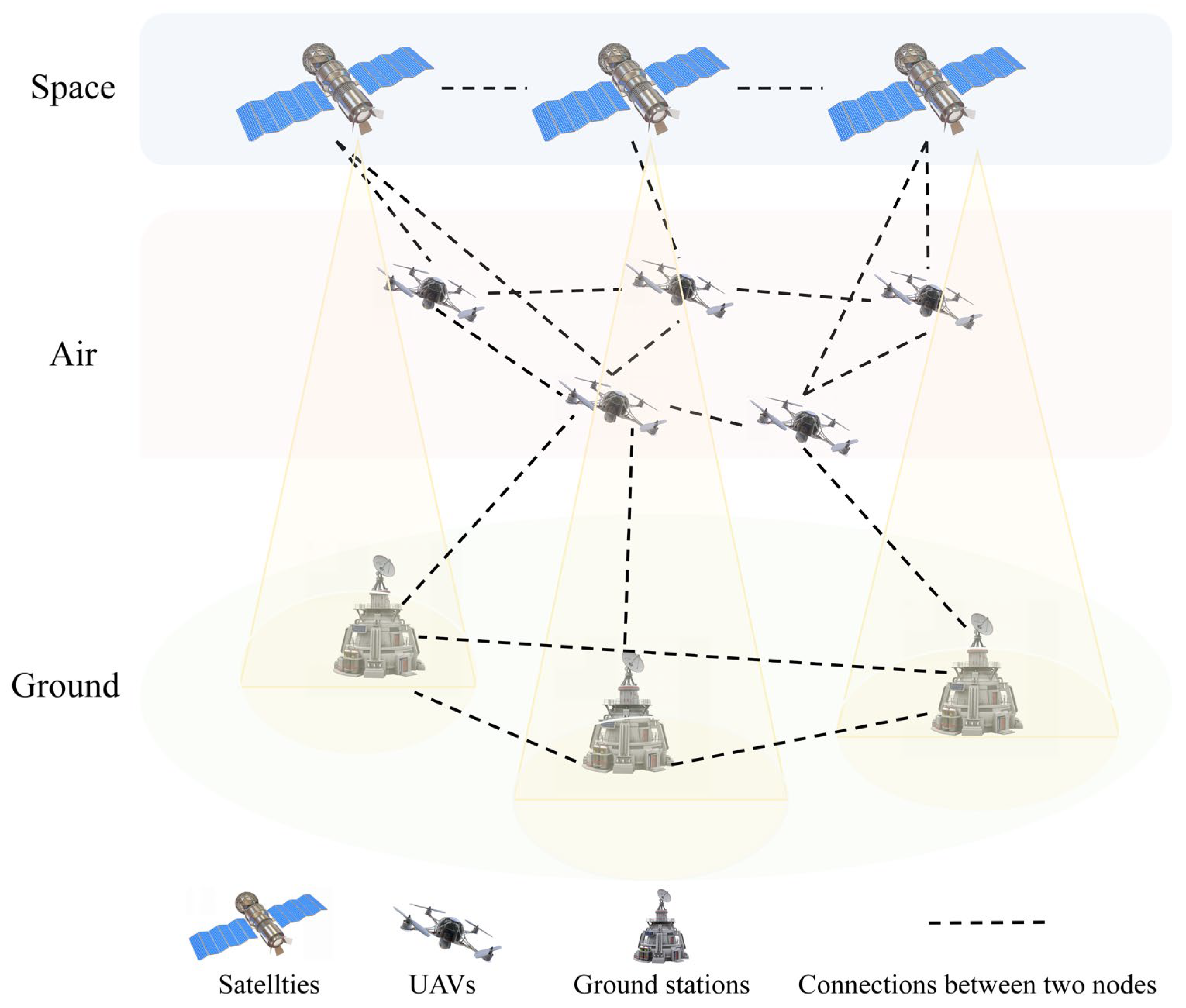

2.1. Network Model

2.2. Optimization Objective

2.3. Challenge Modeling

- Heterogeneity: Networks at different layers have distinct link characteristics and node capabilities, leading to the complexity of cross-domain link scheduling and resource allocation.

- Dynamics: The high-speed movement of satellites and UAVs results in rapid time-varying topological structures, requiring routing algorithms to have high adaptability.

- High-dimensional spatiotemporal data: The combination of spatial (node) and temporal (historical) dimensions leads to a huge data scale , which places extremely high demands on the representation capability and computational efficiency of algorithms.

- In actual deployment, SAGIN may encounter unpredictable sudden anomalies, such as link interruptions caused by extreme weather or temporary satellite failures.

2.4. Symbol Meaning

3. Adopted Methods

3.1. Network State Prediction Model (GCN + Transformer + PSO)

- (1)

- Hybrid encoder framework: We adopt a GCN + Transformer hybrid encoder to process high-dimensional spatiotemporal data and achieve high-precision prediction.

- GCN (spatial dependence): The GCN adopted in this paper belongs to the Spatial Graph Convolutional Network (Spatial GCN). Its core convolution operator is “neighborhood feature weighted aggregation”, and the specific definition is as follows:

- Transformer (temporal dependence): The output of GCN is regarded as a time-series input and fed into the Transformer encoder. The multi-head self-attention mechanism of the Transformer can capture the long-term temporal dependence of indicators such as traffic load and link quality:

- Hybridization and output: The embedding of the GCN is fused with the positional encoding of the Transformer, and finally, the predicted values of latency, bandwidth, and packet loss rate for the next k steps are output through a fully connected layer.

| Algorithm 1 Network state prediction using GCN + Transformer |

| Require: Historical network states , where Ensure: Predicted states 1: Initialize GCN layers and Transformer encoder 2: for each time step to do 3: Compute spatial embeddings: 4: end for 5: Form time-series input: 6: Add positional encoding to 7: Compute temporal dependencies: 8: Predict future states: // latency, bandwidth, packet loss 9: Return predicted graphs from |

- (2)

- The specific configuration of PSO in this paper is designed for high-dimensional mixed search spaces (including integer- and continuous-value parameters), with details as follows:

3.2. Intelligent Routing Algorithm (PPO + Spatiotemporal Attention)

- State space (): Includes the predicted network state results for the next k steps from Section III-A, current service QoS requirements, and global load distribution.

- Action space (): Probability distribution of the next-hop node (discrete) or routing path (continuous).

- Reward function (): Designed as a weighted sum of multi-objective QoS, incentivizing the agent to select paths with low latency, high bandwidth, and low packet loss while considering load balancing u:

- Spatial attention: Enables the agent to focus on important nodes and links in the current topology (e.g., links with high SNR and high remaining bandwidth):

- 2.

- Temporal attention: Enables the agent to focus on key time steps in the prediction sequence (e.g., upcoming peak load moments).

| Algorithm 2 Intelligent routing using PPO with spatiotemporal attention |

| Require: Predicted states , QoS requirements Ensure: Optimal routing policy 1: Initialize Actor network πθ and Critic network 2: while not converged do 3: Collect trajectories using current policy 4: Compute advantages 5: Embed spatiotemporal attention in Actor: 6: for each state in trajectory do 7: Compute spatial attention weights 8: Compute temporal attention over predictions 9: Update action probabilities 10: end for 11: Update policy with clipped surrogate objective: 12: Update Critic with MSE loss 13: end while 14: Return optimized policy |

3.3. Centralized Control and Execution Architecture

- Data collection: G-CCC periodically collects state telemetry data from all network nodes (satellites, UAVs, ground stations) through standard network management protocols to form a spatiotemporal graph database.

- State prediction: G-CCC uses its powerful ground computing resources to run the GCN-Transformer + PSO model in Section III-A to generate the global state prediction graph for the next K steps.

- Routing decision (training): The PPO agent on G-CCC performs reinforcement learning training in an offline or quasi-online manner, using predicted data and reward functions to continuously optimize its Actor–Critic network.

- Policy Execution: After training convergence, G-CCC calculates the optimal path (or routing policy) for carrying QoS services and issues explicit routing rules (e.g., source routing paths or updated forwarding table entries) to key nodes along the path (such as the entry ground station and core satellite nodes) for execution, realizing real-time adjustment of global routing and QoS guarantee.

3.4. Improvement Points

- Spatiotemporal hybrid encoding: Compared with traditional Transformers (only sequence modeling) or GCNs (only spatial modeling), this scheme introduces GCN-Transformer hybrid encoder, which captures both graph structure dependencies and time-series dependencies, significantly improving the representation and prediction ability of SAGIN heterogeneous time-varying topology protocols (such as gRPC telemetry) to form a spatiotemporal graph database.

- PSO automatic optimization: Introducing the PSO algorithm to optimize complex hybrid encoder hyperparameters, replacing tedious and inefficient manual parameter tuning. This helps to avoid the model falling into local optima and improves the generalization ability of the prediction model (expected test set error reduction of 15–20%).

- PPO fusion spatiotemporal attention: Improved the standard PPO algorithm. The spatiotemporal attention mechanism enables agents to automatically filter irrelevant feature interference from high-dimensional spatiotemporal data, focusing on future key nodes and time windows, improving the accuracy and efficiency of decision-making (expected computational complexity reduced by 20–30%).

- Global forward-looking optimization: Different from the local and passive optimization of protocols such as OSPF, as well as the reactive optimization of standard DRL, this solution is based on the global perspective and predictive information of G-CCC, achieving joint and forward-looking optimization across the sky–air–ground three layers, and improving overall resource utilization (expected to increase by 25%).

- Frontier of the scheme: This scheme draws on the latest research results of NeurIPS 2023 on a Dynamic Network Graph Transformer (GNN + Transformer) and IEEE JSAC 2024 on an Evolutionary Algorithm Optimization Transformer, ensuring the forefront of the scheme.

4. Experimental Evaluation and Result Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment and Dataset Setup

- (1)

- Experimental platform and framework: The experimental environment is built based on Python 3.10.

- Core framework: PyTorch (3.10) is used as the deep learning framework to implement the GCN, Transformer, and PPO algorithms.

- Topology generation: The satgenpy library and PyEphem library are utilized. satgenpy can parse TLE (Two-Line Element) data, calculate satellite orbital positions, and generate time-stamp-varying adjacency matrices of satellite networks.

- Graph analysis: NetworkX is used for network graph modeling, path calculation of benchmark algorithms (e.g., OSPF’s Dijkstra), and analysis of network metrics.

- Design reference: The design of the experimental platform refers to the ideas of public satellite network research tools such as StarPerf and Hypatia.

- The manual parameter tuning process: The number of GCN layers was varied across {2~5}, the number of Transformer heads was varied across {4~16}, and the learning rate was varied across

- The combination yielding the minimum validation set MSE was ultimately selected (GCN = 3 layers, Transformer = 8 heads, lr = 1 × 10−3).

- (2)

- Parameterization of SAGIN network topology: We constructed the SAGIN topology based on real constellation and mobility model parameters:

- 1.

- Space tier:

- Constellation model: Walker–Delta constellation based on the Iridium constellation.

- Parameters: 66 satellites, distributed in 6 orbital planes with 11 satellites per plane.

- Orbit: Orbital altitude of 780 km and an inclination of 86.4° (polar orbit).

- Data source: Orbital parameters are initialized using Iridium TLE data provided by CelesTrak.

- Links: Inter-Satellite Laser (ISL) links are set with a bandwidth of 10 Gbps.

- 2.

- Air tier:

- Model: A swarm of 20 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) covering a 10 km × 10 km hot-spot area.

- Mobility: Adopting the 2D random walk (RW) mobility model commonly used in the CRAWDAD dataset.

- Parameters: UAV speeds randomly vary between 5 m/s (low speed) and 20 m/s (high speed).

- 3.

- Ground tier: 50 ground gateways. To realistically simulate large-scale backhaul traffic between the space-based network and the ground-based Internet backbone, we set 50 ground gateway nodes. According to the definition in (IETF RFC 9717), these gateways are core hubs connecting satellite networks and ground wired networks. The positions of these nodes are not randomly distributed but correspond to the locations of 50 major global Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and core data center clusters (e.g., Frankfurt, Ashburn, Singapore, Tokyo, etc.). This ensures that the simulated traffic model (see Section IV-A3) reflects real-world global “satellite–ground gateway” connectivity and stress-tests the algorithm’s performance under “backhaul bottlenecks” (a key challenge identified earlier). The G-CCC (Ground Centralized Control Center) is deployed at one of the major gateway nodes.

- (3)

- Traffic load and QoS model: Traditional network evaluation often uses Poisson distribution to model service arrivals. However, numerous studies have confirmed that real-world Internet traffic (e.g., WAN and LAN traffic) exhibits “bursty” and “self-similar” characteristics, manifested as a “heavy-tailed” distribution. The Poisson model fails to capture such burstiness, leading to over-optimistic evaluations of algorithm performance.

- Average end-to-end delay: For a set of N packets, the average delay is computed as

- Packet loss rate: The ratio of lost packets to the total sent packets:

- QoS satisfaction rate: For real-time video services, the proportion of packets that meet the delay requirement (e.g., delay ≤ 100 ms) is defined as

4.2. Baseline Algorithms

- OSPF (Open Shortest Path First): Serves as the baseline for traditional Interior Gateway Protocol (IGP). In the experiments, it represents a greedy algorithm based on the instantaneous shortest delay path. Under the scenario with 50 ground gateways and highly dynamic topology, its performance is expected to collapse due to the Link State Advertisement (LSA) flooding overhead.

- DDPG-Routing (Advanced DRL Baseline): It is a deep reinforcement learning algorithm based on the Actor–Critic (AC) architecture. Different from DQN which handles discrete Q-values, DDPG (Deep Deterministic Policy Gradients) utilizes a policy network (Actor) to directly output deterministic continuous actions (or high-dimensional discrete actions), making it more expressive than DQN in the high-dimensional and continuous state space of SAGIN (such as precise delay and bandwidth values). Similar to our method, it runs on G-CCC but is essentially reactive, i.e., making decisions based on the current state.

- D2-RMRL (SOTA Meta-RL Baseline): It is a state-of-the-art meta-reinforcement learning (Meta-RL) routing algorithm specifically designed for satellite networks. The core idea of D2-RMRL (Distributed and Distribution-Robust Meta-Reinforcement Learning) is “learn to learn”: it is trained through meta-learning under various network topologies and traffic patterns, enabling it to fast adapt to unseen topology changes or sudden traffic encountered in real SAGIN. This makes it the ultimate test for the robustness and adaptability of our “predictive” model.

- Graph-Mamba-Routing (SOTA GNN Baseline): To fairly compare the effectiveness of our GCN-Transformer encoder, we introduce a baseline based on the 2024 SOTA GNN architecture. This algorithm uses a Graph-Mamba encoder instead of our GCN-Transformer. Mamba (a state space model, SSM) is a major competitor of the Transformer in long sequence modeling, theoretically having equivalent sequence modeling capability and higher computational efficiency. The decision-making end of this baseline also uses PPO to ensure fair comparison, thereby isolating the performance differences of encoders (GCNT vs. Graph-Mamba).

- The proposed method (GCN-T-PPO): The proposed complete scheme. It runs on G-CCC, based on spatiotemporal prediction of a GCN-Transformer and proactive decision-making of PPO.

4.3. Performance Comparison and Analysis

- (1)

- Scenario 1: Performance under different network loads (Poisson traffic):

- Experimental setup: Under the environment, Poisson traffic is injected into the network, with the total load increasing from 10% (low load) to 90% (high congestion).

- Evaluation metrics: (1) Average end-to-end delay (ms); (2) packet loss rate (%).

- (2)

- Scenario 2: QoS satisfaction under bursty traffic (Pareto):

- Experimental setup: Fix the total network load at 70%, and generate bursty traffic using the aforementioned Pareto traffic model. The X-axis represents the burst intensity (the larger the value, the stronger the burst), and the Y-axis represents the QoS satisfaction rate of real-time video services (i.e., the proportion of packets with delay < 100 ms).

4.4. Ablation Study

- (1)

- Experimental setup: Use scenarios with high load and high burstiness. Compare the proposed method with five “incomplete” variants:

- W/o PSO (Remove PSO): Use manually tuned GCN-T hyperparameters. The manual parameter tuning process: The number of GCN layers was varied across {2, 3, 4}, the number of Transformer heads was varied across {4, 6, 8}, and the learning rate was varied across {1 × 10−4, 5 × 10−4, 1 × 10−2}. The combination yielding the minimum validation set MSE was ultimately selected (GCN = 3 layers, Transformer = 8 heads, lr = 5 × 10−4).

- W/o GCN (Transformer Only): Only use Transformer to process sequence data, ignoring topology.

- W/o Transformer (GCN Only): Only use GCN to process instantaneous snapshots, ignoring temporal dependencies.

- W/o Spatiotemporal Attention (Standard PPO): The Actor network of PPO uses standard fully connected layers.

- W/o Predictor (RL Only): i.e., the DQN-Routing baseline, without prediction capability.

- The MSE of W/o PSO is relatively high (0.11), demonstrating the effectiveness of PSO automatic hyperparameter optimization.

- The MSE of W/o GCN is very high (0.25), demonstrating that spatial topology is key information for predicting delay, and time series alone cannot capture the influence of neighboring nodes.

- The MSE of W/o Transformer is the highest (0.32), demonstrating that historical temporal dependencies are also critical, and the current GCN snapshot alone cannot predict congestion trends.

- The reward of W/o Spatiotemporal Attention (Standard PPO) is relatively low (0.80), which demonstrates the value of spatiotemporal attention. The Actor network of standard PPO is overwhelmed by high-dimensional states and cannot distinguish key information. In contrast, the attention mechanism helps PPO focus on the “future congestion points” predicted by GCN-T, leading to more accurate decisions.

- The reward of W/o Predictor (i.e., DQN-Routing) is the lowest (0.65), which again demonstrates that “predictive” decision-making is superior to “reactive” decision-making.

4.5. Scalability Test

- (1)

- Experimental setup: Vary the network scale with the total number of nodes N = {50, 100, 200, 500}. (Small scale corresponds to Iridium, and large scale corresponds to Starlink.)

- (2)

- Evaluation metrics: (1) Computational overhead of GCCC (CPU load %); (2) algorithm convergence time (s).

- D2-RMRL has the longest initial training time (850.5 s when N = 50) because it needs to learn “how to learn”. However, once trained, it demonstrates the hallmark advantage of Meta-RL when facing new topologies (N = 100, 200): extremely fast adaptation time (≤30 s).

- DDPG and Graph-Mamba, as standard DRL/GNN, have their training convergence time increase significantly with N.

- The proposed method (GCN-T-PPO) maintains the fastest and most stable growth in training convergence time across all scales (only 510.9 s when N = 500). This benefits from the inductive learning capability of GNN and the high sample efficiency of PPO (compared to DDPG).

- Computational overhead: When the number of network nodes scales from 50 to 500, the CPU load of this scheme increases nearly linearly (which is lower than the exponential growth of other algorithms). This indicates that the parameter sharing of the GCN and the sample efficiency of PPO effectively control the computational overhead, making it suitable for the limited computing resources of satellite networks.

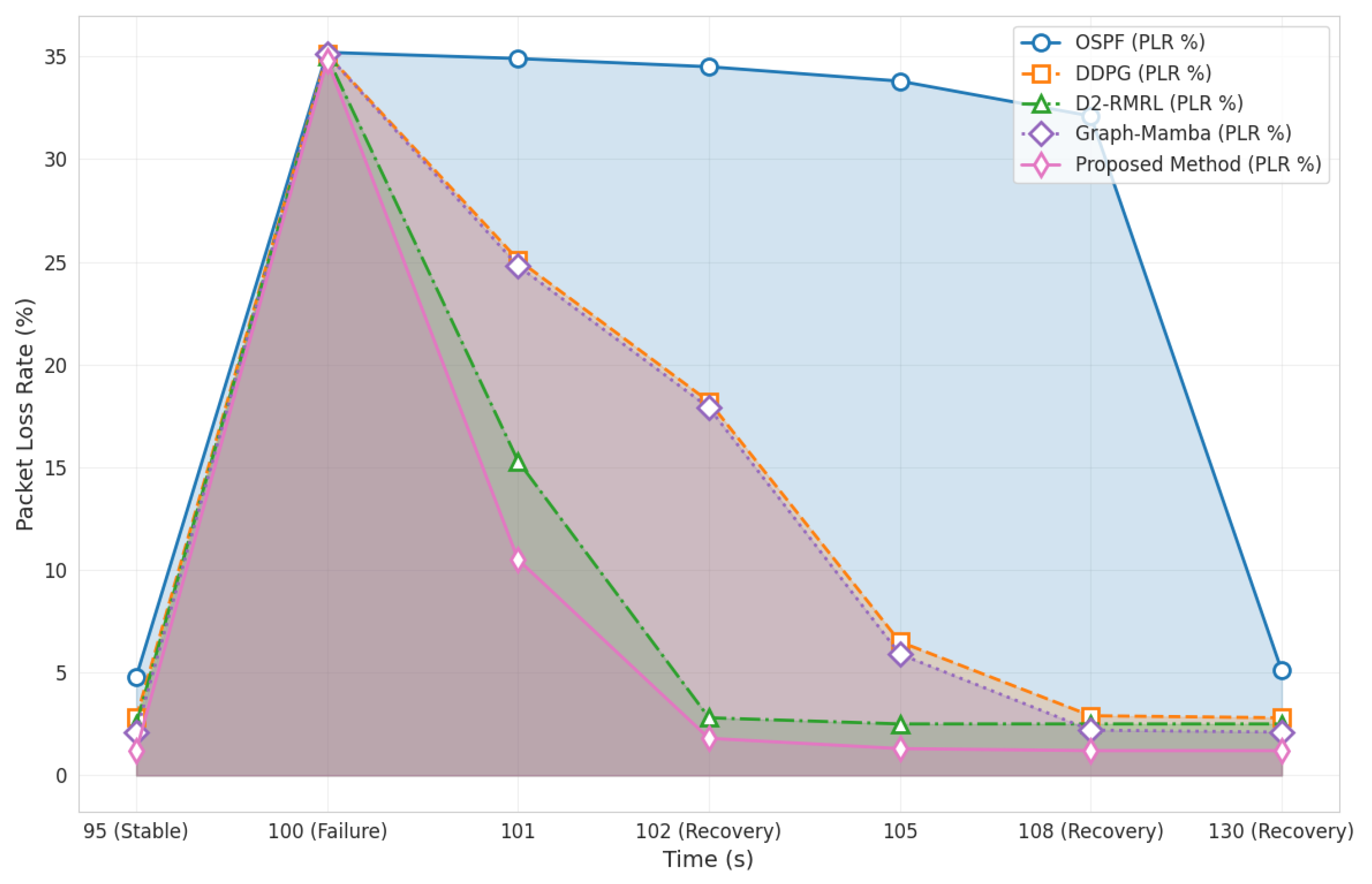

4.6. Robustness Test

- (1)

- Experimental setup: In experiments running stably under high load (80%), at T = 100 s, 10% of Inter-Satellite Links (ISL) in the network fail simultaneously at random.

- (2)

- Evaluation metric: Packet Loss Rate (PLR) over time.

- T = 100 s (failure): With 10% ISL links failing, the PLR of all algorithms surges instantaneously.

- T > 100 s (recovery period):

4.7. Complexity–Performance Trade-Off Optimization

- (1)

- Definition of core parameters:

- Comprehensive QoS performance score : Integrate the three core indicators of delay, packet loss rate, and bandwidth utilization, with weights consistent with the optimization objectives ():

- Computational complexity : It represents the number of floating-point operations per unit time (FLOPs/s) and is decomposed into three major modules:

- Communication complexity : It represents the control signaling overhead (bits/s), which consists of two parts: state reporting and policy issuance:

- (2)

- Weighted complexity metric final formula:

- (3)

- Results and analysis:

5. Conclusions

- Comprehensive performance: In extreme scenarios with high load (80%) and high burstiness (Pareto), the proposed scheme (GCN-T-PPO) significantly outperforms all SOTA baselines in all key QoS metrics. Compared with the suboptimal Graph-Mamba algorithm based on the SOTA GNN, the proposed scheme reduces the average delay (68.9 ms) by 18.6% and the packet loss rate (1.0%) by 73.6%, and it improves the QoS satisfaction rate (91.5%) by 12.7%.

- Component effectiveness: Ablation experiments prove that the combination of the GCN (spatial) and Transformer (temporal) is crucial for prediction accuracy. More importantly, the “spatiotemporal attention” mechanism is the key for the proposed scheme to outperform the Graph-Mamba-PPO baseline, improving the PPO decision efficiency (convergence reward) by about 18.8%.

- Scalability: Thanks to the parameter sharing and inductive capability of the GNN, when the network scale expands, the proposed scheme exhibits SOTA-level computational overhead (CPU load %) and training convergence time (510.9 s, N = 500), significantly outperforming DDPG and D2-RMRL. Additionally, GCN-T-PPO demonstrates superior convergence performance compared to other algorithms.

- Robustness: When facing a sudden failure of 10% of links, the recovery time of the proposed scheme (2 s) is comparable to that of the SOTA Meta-RL algorithm D2-RMRL (2 s), and both are much faster than other reactive baselines (5 s), demonstrating extremely strong network resilience. Moreover, the hyperparameter sets optimized by PSO exhibit strong robustness and generalization capabilities, effectively isolating the inherent advantages of the model architecture itself. This ensures fair performance comparisons across different experimental scenarios.

- Complexity–performance trade-off: This paper further validates the practical value of the GCN-T-PPO algorithm by introducing a weighted complexity metric: under high load (80%) + burst traffic scenarios, the normalized trade-off metric of this algorithm is 1.21, demonstrating a significant improvement over other algorithms.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, F.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M.; Kato, N. The roadmap of com-munication and networking in 6g for the metaverse. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2022, 29, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, N.; He, J.; Yin, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wu, H.; Lyu, F.; Zhou, H.; Shen, X. 6G service-oriented space-air-ground integrated network: A survey. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, J.; Geng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhang, N.; Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Cao, X. Space-air-ground integrated network (SAGIN) for 6G: Requirements, architecture and challenges. China Commun. 2022, 19, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Jamalipour, A.; Zhang, P.; Kim, D.I. Generative AI for space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2024, 31, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tang, F.; Zhao, M.; Kato, N. Outage probability, performance, fairness analysis of space-air-ground integrated network (sagin): Uav altitude and position angle. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 24, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tang, F.; Zhao, M.; Kato, N. Performance analysis of space-air-groun integrated network (sagin): Uav altitude and position angle. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC), Dalian, China, 10–12 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yin, B.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y. Topology aware deep learning for wireless network optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 9791–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arani, A.H.; Hu, P.; Zhu, Y. HAPS-UAV-enabled heterogeneous networks: A deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2023, 4, 1745–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Xiong, X.; Wang, J. Dynamic routings in satellite networks: An overview. Sensors 2022, 22, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Sheng, M.; Li, J. Efficient Air-ground Collaborative Routing Strategy for UAV-assisted MANETs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Wu, Y.; Liao, T.; Cao, Z.; Guo, H.; Sartoretti, G.; Wu, G. Deep reinforcement learning for UAV routing in the presence of multiple charging stations. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 5732–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Mao, B.; Tang, F.; Akashi, O.; Inoue, T.; Mizutani, K. The deep learning vision for heterogeneous network traffic control—Proposal, challenges, and future perspective. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2016, 24, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, F.; Yao, X.; Zhao, M.; Kato, N. Differentiated federated reinforcement learning based traffic offloading on space-airground integrated networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 11000–11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Mao, B.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Kato, N.; Akashi, O.; Inoue, T.; Mizutani, K. On removing routing protocol from future wireless networks: A real-time deep learning approach for intelligent traffic control. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2018, 25, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, Y.; Hwang, S.-H. Guard band protection for coexistence of 5G base stations and satellite earth stations. ICT Express 2023, 9, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Kawamoto, Y.; Kato, N.; Liu, J. Future intelligent and secure vehicular network toward 6g: Machine-learning approaches. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, X.; Ni, W.; Hossain, E.; Wang, X. Distributed machine learning for wireless communication networks: Techniques, architectures, and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1458–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kong, J.H.; Moore, T.J.; Dagefu, F.T. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Routing for Heterogeneous Multi-Hop Wireless Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.14884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Harikrishnan, R.; Kotecha, K. Adaptive routing in wireless mesh networks using hybrid reinforcement learning algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 107961–107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M.A.; Henarejos, P.; Pappalardo, I.; Grechi, E.; Fort, J.; Gil, J.C.; Lancellotti, R.M. Machine learning for satellite communications operations. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahrouj, H.; Liu, S.; Alouini, M.-S. Machine learning-based user scheduling in integrated satellite-HAPS-ground networks. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, C. Task assignment of UAV swarms based on deep reinforcement learning. Drones 2023, 7, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ren, P.; Du, Q. Reinforcement learning routing in space-air-ground integrated networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP), Changsha, China, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Tang, F.; Kato, N. Routing for space-air-ground integrated network with gan-powered deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 11, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Hofner, H.; Kato, N.; Kaneko, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Hangai, M. A deep reinforcement learning-based dynamic traffic offloading in space-air-ground integrated networks (sagin). IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 40, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.S.R.S. Reinforcement learning in dynamic environments: Challenges and future directions. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Data Sci. Mach. Learn. 2025, 6, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xin, X.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, H.; Wang, X.; Tian, Q.; Tian, F. Transformer-Based Spatio-Temporal Traffic Prediction for Access and Metro Networks. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 5204–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Meng, W.; Quek, T.Q.S.; Chen, S. Multi-tier hybrid offloading for computation-aware IoT applications in civil aircraft-augmented SAGIN. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 41, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiko, K.; Kawamoto, Y.; Kato, N.; Ariyoshi, M.; Sugyo, K.; Funada, J. Efficient Coverage Area Control in Hybrid FSO/RF Space-Air-Ground Integrated Networks. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2024–2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 8–12 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.; Song, W.C. Intent-Based Network Resource Orchestration in Space-Air-Ground Integrated Networks: A Graph Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 185057–185077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, A.; Han, C.; Xu, X.; Liang, X.; An, K.; Zhang, Y. Grlr: Routing with graph neural network and reinforcement learning for mega leo satellite constellations. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 3225–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Tonchev, K.; Poulkov, V.; Manolova, A.; Neshov, N.N. Graph-based resource allocation for integrated space and terrestrial communications. Sensors 2022, 22, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, P.; Ros, S.; Song, I.; Kang, S.; Kim, S. A survey of intelligent end-to-end networking solutions: Integrating graph neural networks and deep reinforcement learning approaches. Electronics 2024, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P. An approach to combine the power of deep reinforcement learning with a graph neural network for routing optimization. Electronics 2022, 11, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xiong, R.; Shen, D.; Luo, J. Enhancing Network Traffic Prediction by Integrating Graph Transformer with a Temporal Model. In Proceedings of the 9th Asia-Pacific Workshop on Networking, Shanghai, China, 7–8 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, L.; Yu, M.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Miao, Y.; Yuan, H. Network traffic prediction: Apply the transformer to time series forecasting. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8424398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Liu, G.; Sun, G.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, W.; Niyato, D.; Kim, D.I. Joint AoI and Handover Optimization in Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.12716. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Kumar, N.; Chen, N.; Hsu, C.-H.; Barnawi, A. Distributed deep reinforcement learning assisted resource allocation algorithm for space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 20, 3348–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Ye, Z.; Song, G.; Jiang, X.; Manolova, A.; Neshov, N.N. Space-Air-Ground Integrated Mobile Crowdsensing for Partially Observable Data Collection by Multi-Scale Convolutional Graph Reinforcement Learning. Entropy 2022, 24, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Cheng, P.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, W.; Vucetic, B.; Li, Y. Graphic Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Resource Allocation in Space-Air-Ground Integrated Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2024, 43, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Alnajjar, K.A.; Majzoub, S.; Almajali, E.; Jarndal, A.; Bonny, T.; Hussain, A.; Mahmoud, S. Attention-Enhanced Hybrid Automatic Modulation Classification for Advanced Wireless Communication Systems: A Deep Learning-Transformer Framework. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 105463–105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miuccio, L.; Panno, D.; Riolo, S. A flexible encoding/decoding procedure for 6G SCMA wireless networks via adversarial machine learning techniques. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 3288–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Dynamic spatiotemporal graph | |

| Node set (satellites, UAVs, ground nodes) | |

| Edge set (communication links) | |

| Time dimension | |

| Adjacency matrix at time | |

| Node feature matrix at time | |

| Set of all routing paths | |

| End-to-end latency of path | |

| Normalized minimum bandwidth of path | |

| Cumulative packet loss rate of path | |

| Weights for multi-objective optimization | |

| Node embeddings at GCN layer | |

| Normalized adjacency matrix | |

| Query, key, value matrices in attention | |

| Dimension of keys in attention | |

| Velocity of particle at iteration in PSO | |

| Position of particle at iteration in PSO | |

| State space in reinforcement learning | |

| Action space in reinforcement learning | |

| Reward function | |

| Spatial attention weight between nodes and |

| Category | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental platform | Core framework Topology generation | Python 3.10 + PyTorch satgenpy, NetworkX |

| Space-tier network | Constellation Orbital altitude/inclination TLE data source Inter-satellite link (ISL) | Iridium-like (Walker 66/6/11) 780 km/86.4° CelesTrak (2025 data) Gbps (Laser) |

| Air-tier network | Number of nodes Mobility odel Mobility speed Data source | 20 UAVs Random walk (RW) 5–20 m/s CRAWDAD mobility statistics |

| Ground-tier network | Number of nodes Topology role | 50 ground gateways (IXPs) Global backhaul gateway |

| Traffic model | Traffic arrival Traffic burstiness Traffic Characteristics | Poisson distribution Pareto distribution CAIDA 100G link statistics |

| Algorithm model | Predictor (GCN) Predictor (Transformer) Reinforcement learning Training epochs Optimizer Discount factor (γ) PPO clipping parameter (ε) Hardware | 3 layers 4 layers, 8 heads PPO (clipped) 1000 epochs Adam 0.95 0.2 NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU |

| Network Load (%) | OSPF (ms) | DDPG-Routing (ms) | D2-RMRL (ms) | Graph-Mamba (ms) | Proposed Method (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 36.1 | 42.1 | 41.5 | 38.2 | 35.9 |

| 30 | 42.5 | 49.8 | 48.9 | 45.1 | 40.3 |

| 50 | 115.3 | 70.2 | 64.8 | 58.9 | 50.2 |

| 70 | 240.8 | 105.6 | 85.3 | 74.5 | 61.5 |

| 90 | 410.2 | 160.4 | 125.1 | 98.8 | 80.4 |

| Experimental Variant | Predictor Mean Squared Error |

|---|---|

| W/o PSO (Manual Tuning) | 0.11 |

| W/o GCN (Transformer Only) | 0.25 |

| W/o Transformer (GCN Only) | 0.32 |

| Proposed Method (GCN-T + PSO) | 0.04 |

| Experimental Variant | Final Convergence Average Reward |

|---|---|

| W/o Spatiotemporal Attention | 0.80 |

| W/o Predictor | 0.65 |

| Proposed Method | 0.95 |

| Total Number of Nodes (N) | OSPF (CPU %) | DDPG (CPU %) | D2-RMRL (CPU %) | Graph-Mamba (CPU %) | Proposed Method (CPU %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 18.5 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| 100 | 22.1 | 18.1 | 40.2 | 8.3 | 9.6 |

| 200 | 48.9 | 38.5 | 85.1 (OOM) | 13.5 | 15.7 |

| 500 | 85.3 | 80.2 | Failed | 26.1 | 29.8 |

| Total Number of Nodes (N) | OSPF (s) | DDPG (s) | D2-RMRL (s) | Graph-Mamba (s) | Proposed Method (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 5.2 | 410.1 | 850.5 (Training) | 320.4 | 305.1 |

| 100 | 12.8 | 980.2 | 25.1 (Adaptation) | 410.8 | 380.6 |

| 200 | 30.1 | 1850.6 | 28.3 (Adaptation) | 501.2 | 450.3 |

| 500 | 80.5 | 4100.3 | 35.8 (Adaptation) | 620.5 | 510.9 |

| Total Number of Nodes (N) | PSO Optimized Hyperparameters (MSE) | Manually Tuned Hyperparameters (MSE) | Random Hyperparameters (MSE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.038 | 0.105 | 0.286 |

| 100 | 0.042 | 0.112 | 0.295 |

| 200 | 0.045 | 0.128 | 0.312 |

| 500 | 0.048 | 0.142 | 0.338 |

| Average MSE | 0.043 | 0.122 | 0.308 |

| Experimental Variant | ||

|---|---|---|

| OSPF | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| DDPG-Routing | 0.65 | 0.14 |

| D2-RMRL | 0.78 | 0.10 |

| Graph-Mamba | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| Proposed Method | 0.92 | 1.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J. Intelligent Routing Optimization via GCN-Transformer Hybrid Encoder and Reinforcement Learning in Space–Air–Ground Integrated Networks. Electronics 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010014

Liu J, Li S, Li X, Zhang F, Wang J. Intelligent Routing Optimization via GCN-Transformer Hybrid Encoder and Reinforcement Learning in Space–Air–Ground Integrated Networks. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jinling, Song Li, Xun Li, Fan Zhang, and Jinghan Wang. 2026. "Intelligent Routing Optimization via GCN-Transformer Hybrid Encoder and Reinforcement Learning in Space–Air–Ground Integrated Networks" Electronics 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010014

APA StyleLiu, J., Li, S., Li, X., Zhang, F., & Wang, J. (2026). Intelligent Routing Optimization via GCN-Transformer Hybrid Encoder and Reinforcement Learning in Space–Air–Ground Integrated Networks. Electronics, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010014