Knowledge-Enhanced Zero-Shot Graph Learning-Based Mobile Application Identification

Abstract

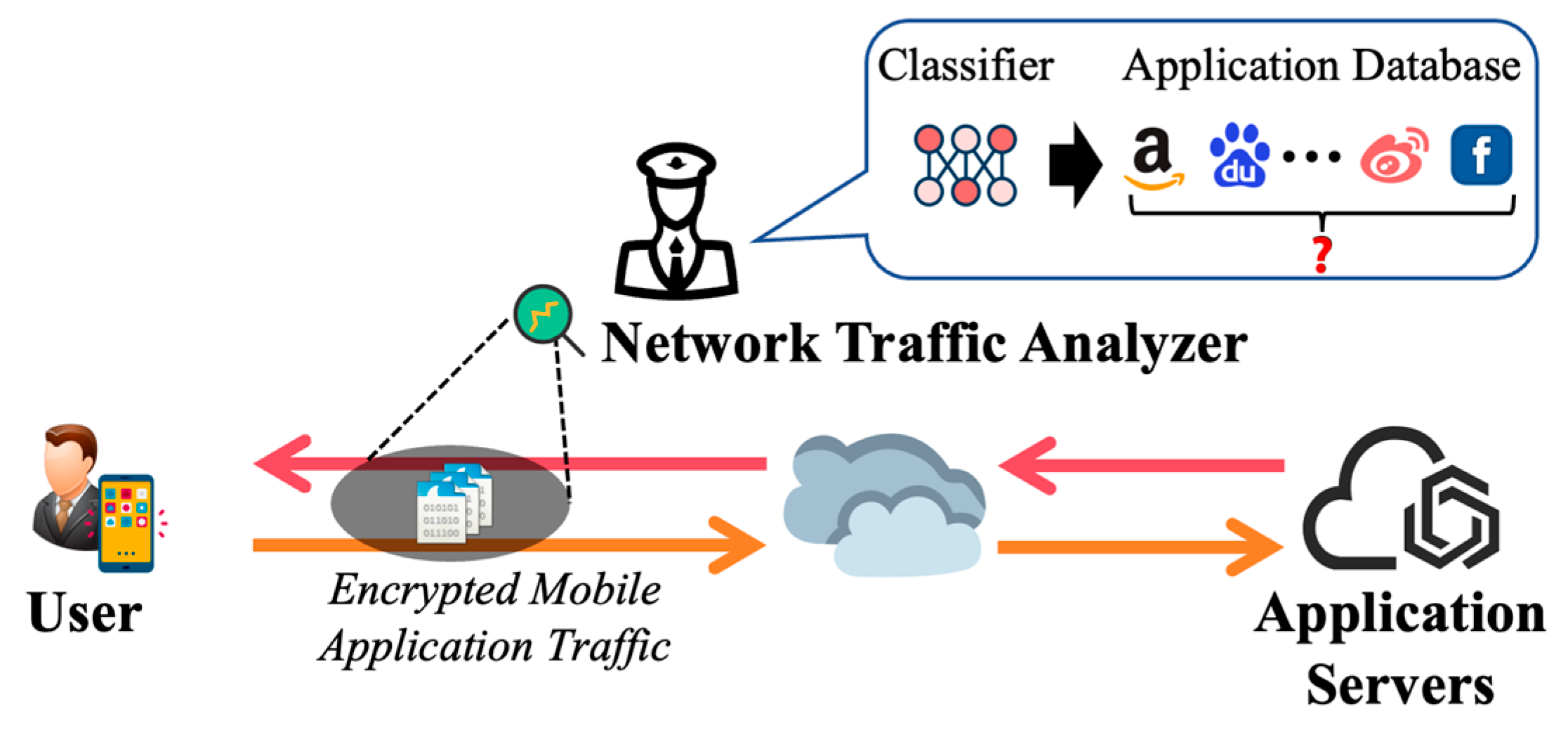

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We present KZGNN, a knowledge-enhanced zero-shot graph learning framework for mobile application identification that supports recognition of categories absent during training. Its core novelty lies in constructing and exploiting a unified cross-view knowledge graph that tightly integrates semantic metadata with dynamic traffic behaviors through explicit relational alignment. KZGNN preserves structural dependencies across views and aligns heterogeneous representations at the entity, relation, and attribute levels. This cross-view relational foundation enables the model to reason jointly over semantic context and communication behavior, achieving robust generalization to previously unseen applications.

- (2)

- We design a zero-shot graph neural network that incorporates two key algorithmic innovations: a relation-aware dual-channel propagation mechanism and a structure-preserving semantic alignment module. The dual-channel design separates semantic and behavioral relations into dedicated propagation pathways, applies edge attribute-aware weighting, and adaptively fuses complementary information through attention. The alignment module maps node embeddings and category semantics into a unified embedding space while preserving global semantic structure, yielding discriminative and transferable representations for previously unseen categories.

- (3)

- We conduct a comprehensive evaluation on a real-world dataset comprising 160 mobile applications to validate the robustness and generalization capability of KZGNN. The classification results show that KZGNN consistently outperforms nine state-of-the-art baselines, achieving a 5.2% improvement in unknown application category identification accuracy. These results show that knowledge-enhanced graph modeling and zero-shot semantic alignment provide substantial benefits for recognizing emerging and previously unseen mobile applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Known Application Identification

2.2. Unknown Application Identification

3. Preliminary

3.1. Threat Model

3.2. Basic Element of the Knowledge Graph

4. Proposed Method

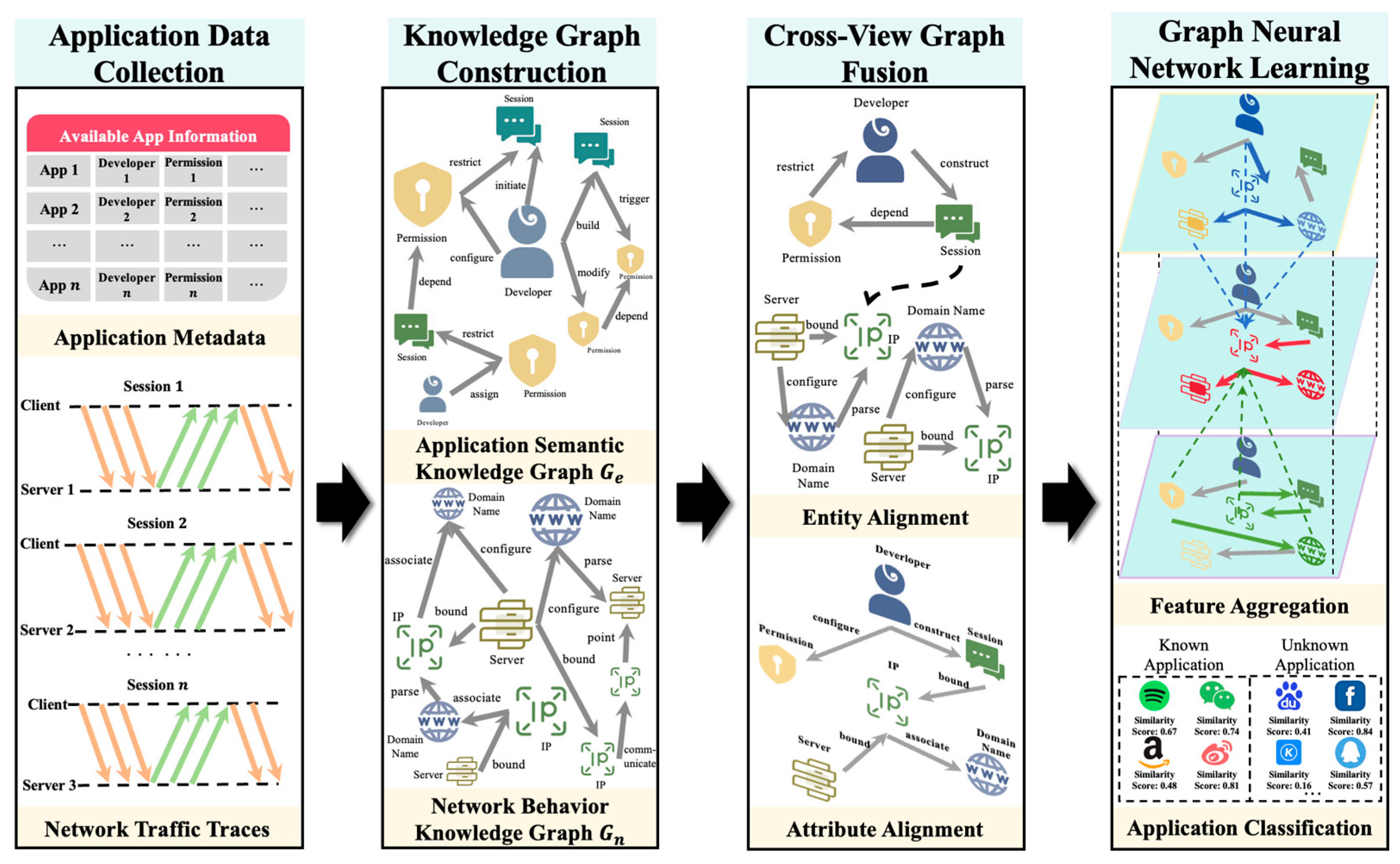

4.1. Overview

4.2. Mobile Application Knowledge Graph Construction

4.3. Cross-View Knowledge Graph Fusion

4.4. Zero-Shot Graph Neural Network Design

5. Experiment Results and Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Dataset

5.1.2. Baselines for Performance Evaluation

5.1.3. Performance Metrics

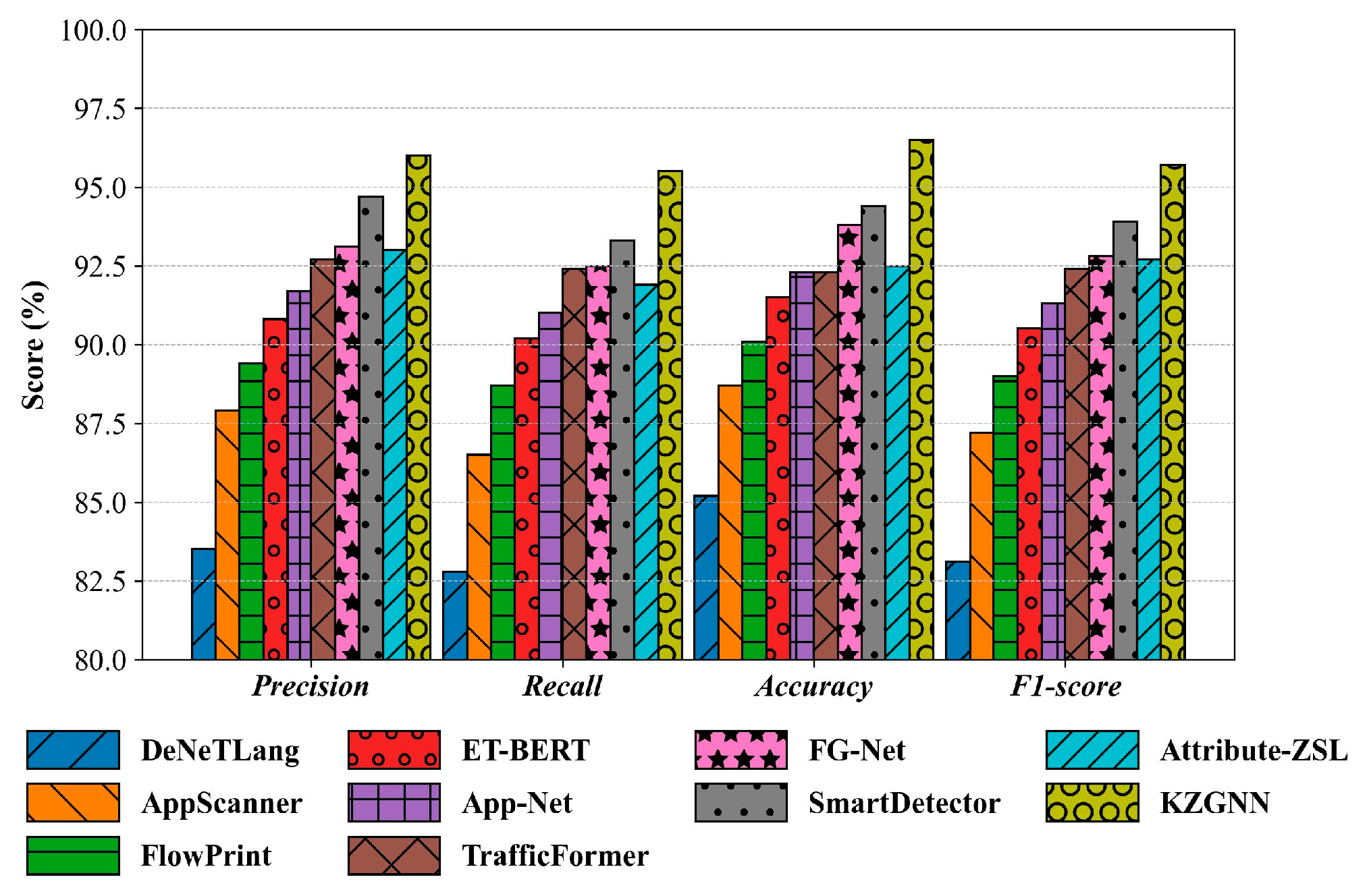

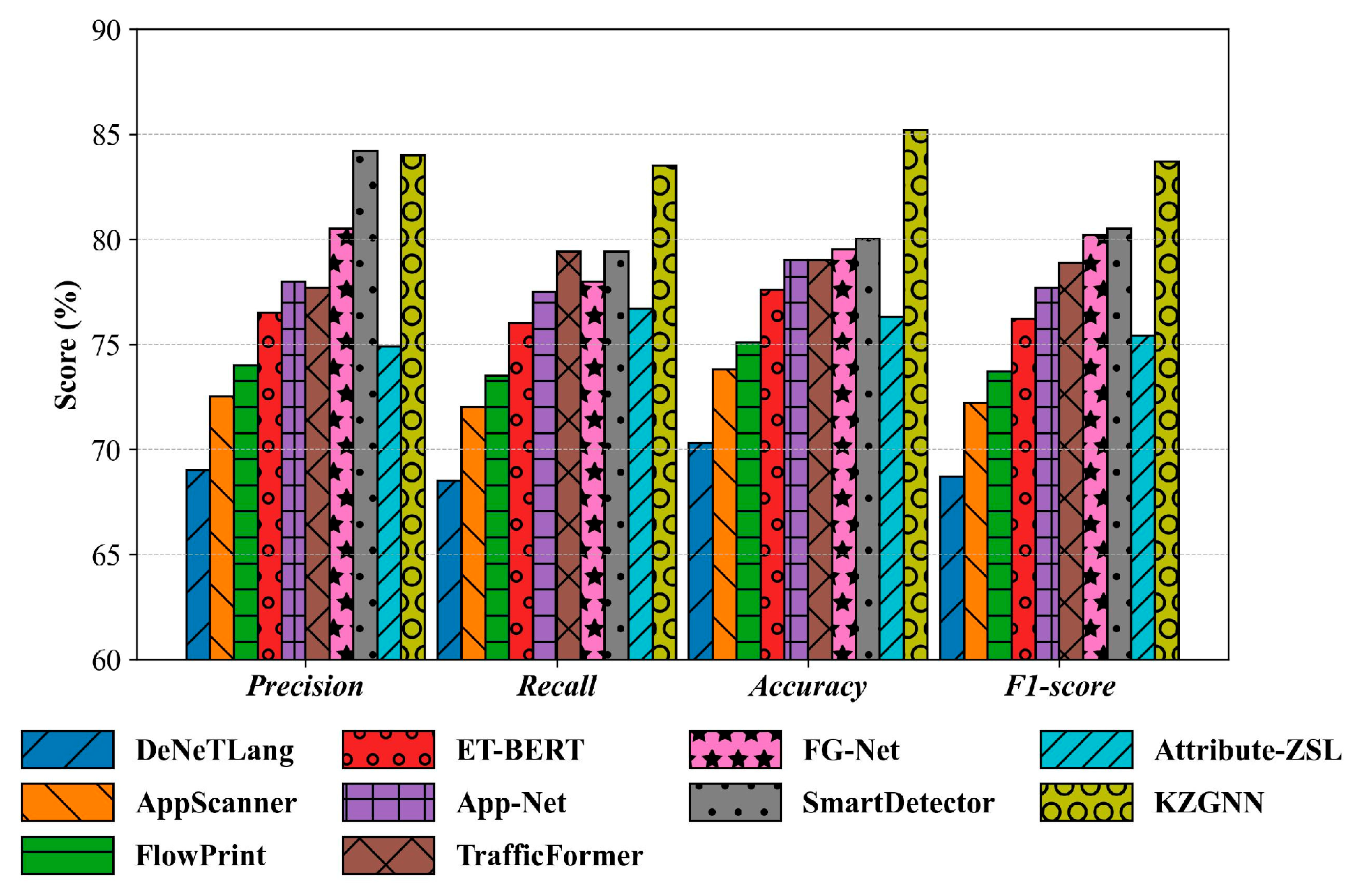

5.2. Unknown Application-Aware Classification Experiments

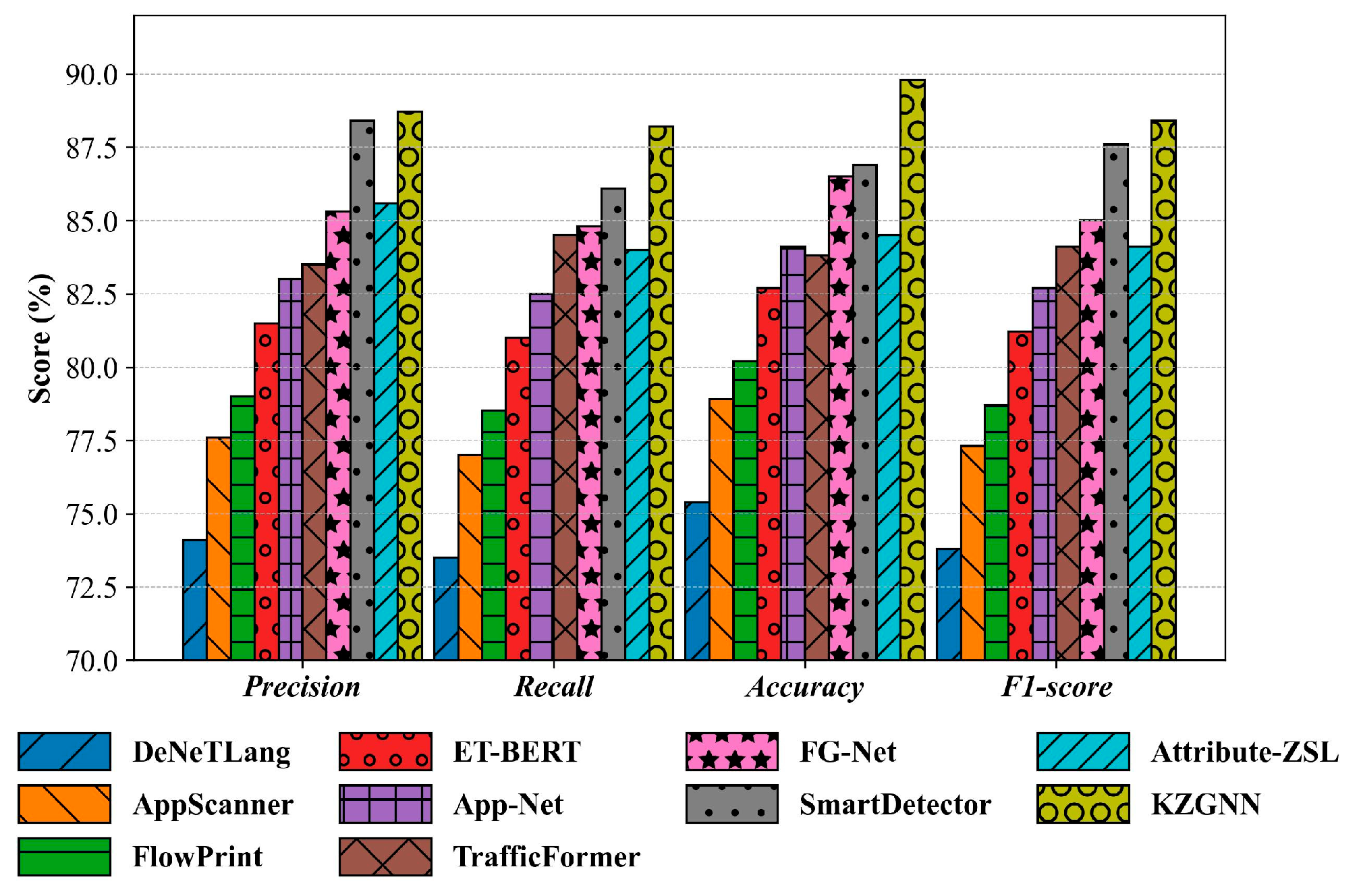

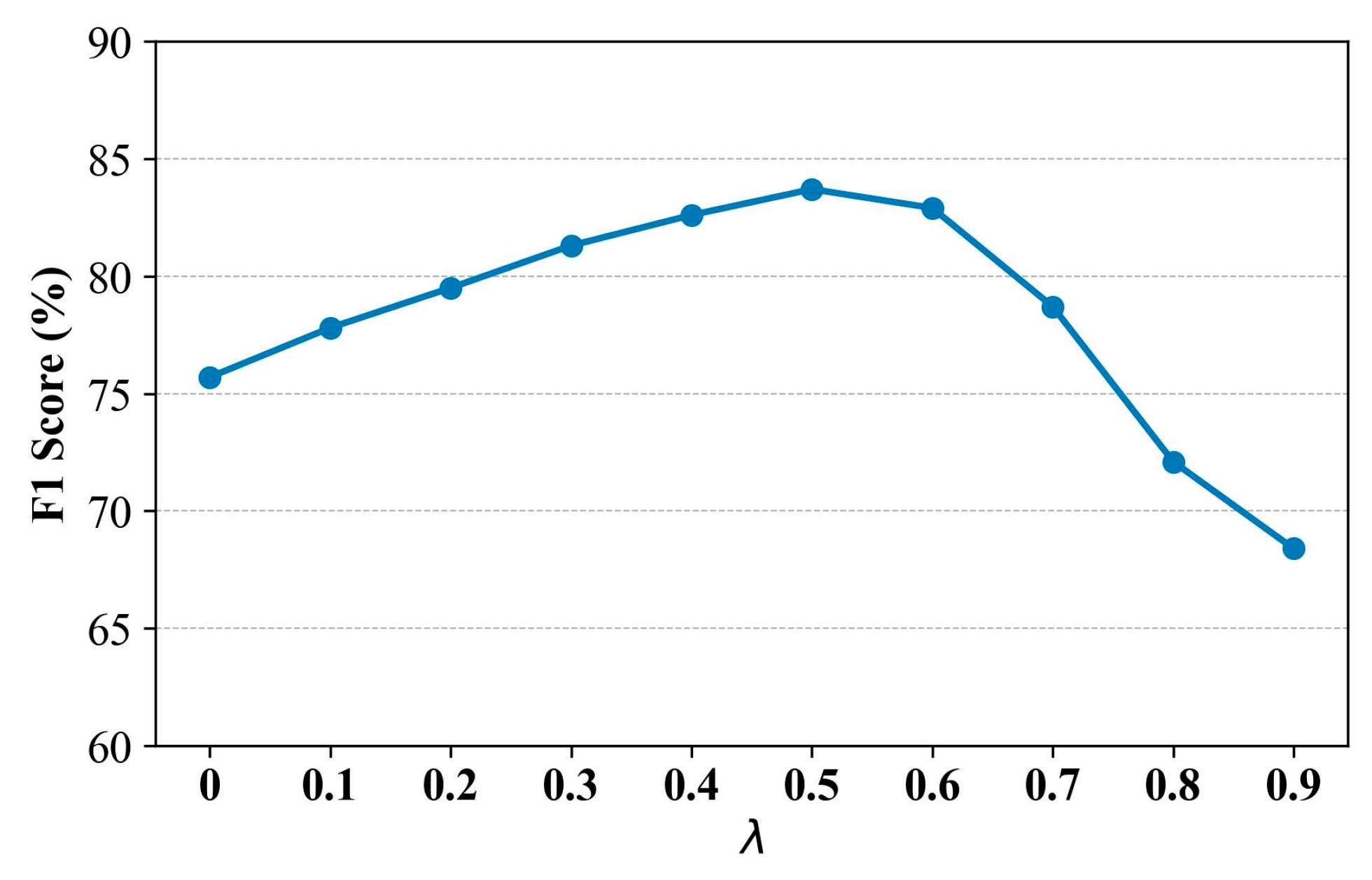

5.3. Unknown Application Type-Aware Classification Experiments

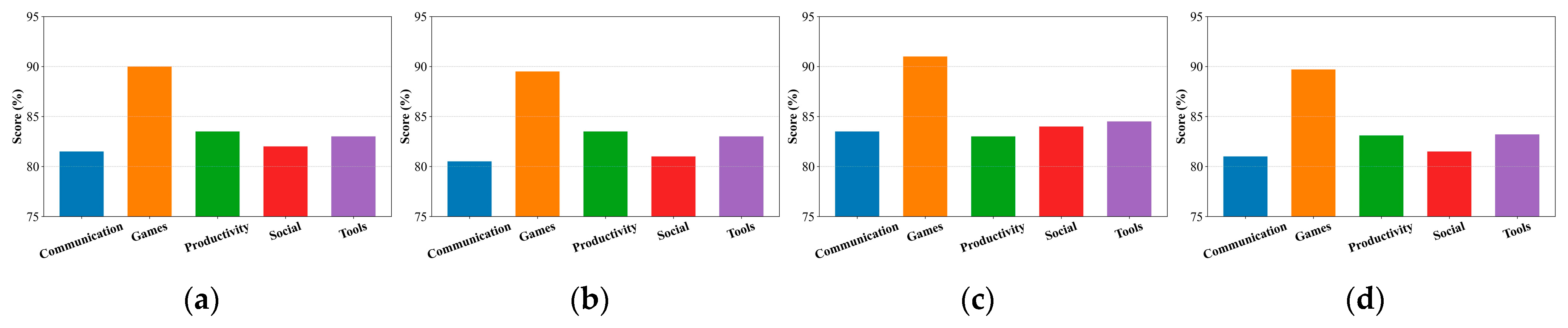

5.4. Unknown Application Label-Aware Classification Experiments

5.5. Temporal Drift Experiments

5.6. Ablation Experiments

5.7. Computing Efficiency Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tauqeer, M.; Gohar, M.; Koh, S.; Alquhayz, H. Use of QUIC for mobile-oriented future Internet. Electronics 2024, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Chandra, B. Two decades of M-commerce consumer research: A bibliometric analysis using R biblioshiny. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU. Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures. 2025. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/facts-figures-2025/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Azab, A.; Khasawneh, M.; Alrabaee, S.; Choo, K.; Sarsour, M. Network traffic classification: Techniques, datasets, and challenges. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Ye, K.; Hu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, C. A novel multimodal deep learning framework for encrypted traffic classification. IEEE/ACM Trans. Net. 2023, 31, 1369–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Ye, K.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Kang, J.; Yu, S.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. Machine learning-powered encrypted network traffic analysis: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, Q.; Song, Q.; Duan, C. Fine-grained encrypted traffic classification using dual embedding and graph neural networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.; Bortolameotti, R.; Continella, A.; Ren, J.; Dubois, D.; Lindorfer, M.; Choffnes, D.; Van, M.; Peter, A. Flowprint: Semi-supervised mobile-app fingerprinting on encrypted network traffic. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2020; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenzi, G.; Monda, D.; Montieri, A.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. Few shot learning approaches for classifying rare mobile-app encrypted traffic samples. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 20 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, G.; Chen, W.; Jiang, B. Attribute-based zero-shot learning for encrypted traffic classification. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 4583–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Gu, Z.; Bai, J.; Li, Z.; Xiong, G.; Gou, G.; Yao, S.; Chen, X. Few-shot encrypted traffic classification: A survey. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers, Dalian, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 646–652. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Yu, J.; Lin, X.; Gou, G.; Xiong, G. Deep learning and pre-training technology for encrypted traffic classification: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 128444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskovic, S.; Lee, G.; Liao, Y.; Baldi, M. Appprint: Automatic fingerprinting of mobile applications in network traffic. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Passive and Active Network Measurement, New York, NY, USA, 19–20 March 2015; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, V.; Spolaor, R.; Conti, M.; Martinovic, I. Appscanner: Automatic fingerprinting of smartphone apps from encrypted network traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy, Saarbruecken, Germany, 21–24 March 2016; pp. 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, V.; Spolaor, R.; Conti, M.; Martinovic, I. Robust smartphone app identification via encrypted network traffic analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Montieri, A.; Pescapé, A. Multi-classification approaches for classifying mobile app traffic. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 103, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D. Identify what you are doing: Smartphone apps fingerprinting on cellular network traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications, Athens, Greece, 5–8 September 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, S.; Kroencke, B.; Liu, X. Large-scale mobile app identification using deep learning. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Montieri, A.; Pescapè, A. MIMETIC: Mobile encrypted traffic classification using multimodal deep learning. Comput. Netw. 2019, 165, 106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Su, J. App-net: A hybrid neural network for encrypted mobile traffic classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 424–429. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Su, J. Automatic mobile app identification from encrypted traffic with hybrid neural networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 182065–182077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Su, J. Real network traffic collection and deep learning for mobile app identification. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2020, 2020, 4707909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Montieri, A.; Pescapé, A. Toward effective mobile encrypted traffic classification through deep learning. Neurocomputing 2020, 409, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, T.; Shavitt, Y. FlowPic: A generic representation for encrypted traffic classification and applications identification. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xiong, G.; Gou, G.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Yu, J. Et-bert: A contextualized datagram representation with pre-training transformers for encrypted traffic classification. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Xu, K.; Du, X. Accurate decentralized application identification via encrypted traffic analysis using graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 2367–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Ho, T.; Truong, T.; Cao, T.D.; Truong, H.L. Mappgraph: Mobile-app classification on encrypted network traffic using deep graph convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, Virtual, 6–10 December 2021; pp. 1025–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Li, Z.; Fu, P.; Cai, W.; Cui, M.; Xiong, G.; Gou, G. Accurate mobile-app fingerprinting using flow-level relationship with graph neural networks. Comput. Netw. 2022, 217, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huoh, T.; Luo, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, T. Flow-based encrypted network traffic classification with graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 20, 1224–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Gao, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Q.; Zang, T.; Chen, F. FusionTC: Encrypted app traffic classification using decision-level multimodal fusion learning of flow sequence. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2023, 2023, 9118153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzani, F.; Ghassemi, F.; Sabahi, Z.; Van, T.; Van, M. Mobile app fingerprinting through automata learning and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IFIP Networking Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 12–15 June 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Li, S.; Cheng, Z.; Qin, R.; Xie, J.; Sun, P. Trafficgcn: Mobile application encrypted traffic classification based on gcn. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 891–896. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Cui, M.; Liu, C.; Gou, G.; Xiong, G.; Li, Z. Zero-relabelling mobile-app identification over drifted encrypted network traffic. Comput. Netw. 2023, 228, 109728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenzi, G.; Monda, D.; Montieri, A.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. META MIMETIC: Few-shot classification of mobile-app encrypted traffic via multimodal meta-learning. In Proceedings of the 35th International Teletraffic Congress, Turin, Italy, 3–5 October 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tong, Y.; Hwee, G.; Cao, Q.; Razul, S.; Lin, Z. Encrypted mobile traffic classification with a few-shot incremental learning approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE 18th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, Ningbo, China, 18–22 August 2023; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, S.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Z.; Su, J. Identifying known and unknown mobile application traffic using a multilevel classifier. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 9595081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, T.; Zhan, X.; Ma, X. FOAP: Fine-grained open-world android app fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 1579–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, S.; Zhou, H.; Luo, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X. Packet-level open-world app fingerprinting on wireless traffic. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Guo, Z.; Qin, Z.; Ren, K. SnWF: Website fingerprinting attack by ensembling the snapshot of deep learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2022, 17, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Hao, Z.; Liu, A. Reliable open-set network traffic classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 2313–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamo, J.; Guaman, D.; Balmori, B.; Diez, A. Privacy assessment in android apps: A systematic mapping study. Electronics 2021, 10, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabahi, Z.; Ghassemi, F. An encrypted traffic classifier via combination of deep learning and automata learning. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 13443–13460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. Trafficformer: An efficient pre-trained model for traffic data. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 May 2025; pp. 1844–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Wu, J.; Ye, K.; Xu, K.; Xiong, G.; Zhu, L. Robust detection of malicious encrypted traffic via contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 4228–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Representative Mobile Application Names (Available Online: https://play.google.com/store/games, Accessed on 12 December 2025) |

|---|---|

| Social | Facebook, TikTok, X (Twitter), Reddit, Instagram |

| Communication | WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, Skype, Zoom |

| Games | Fortnite, EA SPORTS FC Mobile, PUBG Mobile, LifeAfter, Age of Empires Mobile |

| Tools | Google Chrome, Google Maps, Microsoft Authenticator, Google Drive, ES File Explorer |

| Productivity | Microsoft Outlook, Notion, Trello, Slack, Google Docs |

| Comparison | 95% CI | Wilcoxon p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KZGNN vs. FG-Net | +3.50% | [2.02, 4.98] | 0.031 |

| KZGNN vs. SmartDetector | +3.24% | [2.46, 4.02] | 0.031 |

| KZGNN vs. TrafficFormer | +4.82% | [2.35, 7.29] | 0.031 |

| Method | DeNeTLang | AppScanner | FlowPrint | ET-BERT | App-Net | TrafficFormer | FG-Net | SmartDetector | Attribute-ZSL | KZGNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | 24.0 | 32.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 20.0 | 48.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 32.0 | 68.0 |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KZGNN w/o KG/ZSL | 77.5 ± 0.4 | 77.0 ± 0.4 | 78.5 ± 0.3 | 77.2 ± 0.3 |

| KZGNN w/o KG | 80.0 ± 0.3 | 79.5 ± 0.3 | 81.0 ± 0.2 | 79.7 ± 0.2 |

| KZGNN w/o ZSL | 81.7 ± 0.3 | 81.2 ± 0.3 | 82.8 ± 0.2 | 81.4 ± 0.1 |

| KZGNN | 84.0 ± 0.2 | 83.5 ± 0.2 | 85.2 ± 0.1 | 83.7 ± 0.1 |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KZGNN w/TF-IDF | 71.3 ± 0.3 | 67.1 ± 0.4 | 68.6 ± 0.4 | 64.6 ± 0.4 |

| KZGNN w/BERT | 79.3 ± 0.1 | 81.0 ± 0.0 | 80.9 ± 0.1 | 80.2 ± 0.0 |

| KZGNN w/RoBERTa | 76.3 ± 0.2 | 81.8 ± 0.1 | 80.7 ± 0.1 | 78.8 ± 0.1 |

| KZGNN w/Sentence-BERT | 80.1 ± 0.1 | 82.5 ± 0.1 | 84.7 ± 0.1 | 80.2 ± 0.1 |

| KZGNN | 84.0 ± 0.2 | 83.5 ± 0.2 | 85.2 ± 0.1 | 83.7 ± 0.1 |

| Method | DeNeTLang | AppScanner | FlowPrint | ET-BERT | App-Net | TrafficFormer | FG-Net | SmartDetector | Attribute-ZSL | KZGNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATC (ms) | 28.6 | 31.6 | 47.7 | 974.6 | 54.8 | 983.7 | 55.6 | 132.6 | 285.8 | 207.7 |

| AIC (ms) | 3.5 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 43.5 | 5.5 | 44.0 | 7.1 | 19.5 | 24.8 | 28.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Huang, J.; Tian, M.; Guan, L. Knowledge-Enhanced Zero-Shot Graph Learning-Based Mobile Application Identification. Electronics 2026, 15, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010126

Zhang D, Huang J, Tian M, Guan L. Knowledge-Enhanced Zero-Shot Graph Learning-Based Mobile Application Identification. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dongfang, Jianan Huang, Manjun Tian, and Lei Guan. 2026. "Knowledge-Enhanced Zero-Shot Graph Learning-Based Mobile Application Identification" Electronics 15, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010126

APA StyleZhang, D., Huang, J., Tian, M., & Guan, L. (2026). Knowledge-Enhanced Zero-Shot Graph Learning-Based Mobile Application Identification. Electronics, 15(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010126