1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of industrial automation, the quality inspection of precision components is shifting from manual screening to intelligent discrimination. In critical sectors such as automotive and machinery manufacturing, oil seals serve as core sealing elements. Defects such as scratches, deformations, or bubbles on their surfaces can readily become potential triggers for equipment failure and safety incidents. Particularly for industrial oil seals that are operating perpetually under high temperature and pressure, minor defects can be drastically amplified under extreme conditions. If such defective products enter the market, they can lead to severe equipment failure and safety hazards. Hence, developing accurate and stable intelligent inspection solutions is essential for mitigating such risks and enhancing product quality control.

In the early stages of the development of defect detection technology, computer vision methods based on traditional image processing (e.g., edge detection and morphological operations) dominated. However, these methods are typically only suitable for defects with distinct geometric features and simple, intuitive scenarios; they exhibit weak generalization performance and struggle to meet the complex requirements of modern defect detection. In recent years, the rise of deep learning has greatly advanced the field of defect detection. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), renowned for their powerful features of learning capabilities, have emerged as a highly promising focus in research. Models such as the mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN) [

1], which achieved the best single-model performance in the 2017 COCO challenge through framework innovation and precise design localization, and Transformer [

2], which popularized the attention mechanism and enabled large models to gradually demonstrate cognitive abilities surpassing humans in certain tasks, exemplify this trend. However, the increasing complexity of these models leads to significant computational and memory costs, limiting their deployment for resource-constrained edge devices [

3,

4,

5].

The Ultralytics YOLO series [

6] has gained prominence in the field of single-stage object detection because of its excellent real-time performance and open-source ecosystem. There are numerous classical applications of YOLO for defect detection [

7,

8]. Nonetheless, its earlier versions performed poorly in detecting small defects; according to official YOLO documentation, YOLOv5s achieved an mAP@0.5 of 56.8% on the COCO val2017 dataset, which falls short of the requirements for industrial applications.

To address the low accuracy and weak generalization of traditional methods in detecting minute oil seal defects, we propose YOLOv11n_CDK. While existing lightweight YOLO improvements typically focus on integrating singular advanced modules, our key innovation lies in the synergistic combination of three complementary components that collectively address specific limitations in current YOLOv11n-based defect detection research.

Our work fills critical gaps in recent YOLOv11n research through the following integrated approach:

- (1)

Differentiated Convolutional Design for Dynamic Defects:

Building upon established dynamic convolutions including Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution (ODConv) [

9], Conditionally Parameterized Convolution (CondConv) [

10], and FMDConv [

11], and informed by experimental comparison with structures such as context-mixing dynamic convolution (ContMix) [

12] and the lightweight multireceptive visual mamba network (MobileMamba) [

13], we designed and created three distinct dynamic convolutional structures that integrate Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention [

14]. These replace the C3 module and employ differentiated dynamic kernel generation mechanisms, specifically addressing the limitation of static convolutional kernels in handling varied defect morphologies.

- (2)

Addressing Irreversible Feature Loss:

Current pooling strategies and the original SPPF module typically cause irreversible loss of fine-grained features crucial for small defect recognition. Our Nested Asynchronous Pooling Convolution (NAPConv) module specifically addresses this limitation by decoupling feature fusion from information concentration through nested multi-scale asynchronous pooling, effectively preserving critical spatial details while ensuring robust feature fusion.

- (3)

Enhanced Nonlinear Representation for Small Targets:

Moving beyond the fixed activation functions of conventional CNNs and drawing inspiration from the inception module concept from “Going deeper with convolutions” [

15], we incorporate a customized Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) [

16] at the backbone terminus. This innovative integration enables dynamic, data-driven nonlinear transformations, significantly strengthening complex feature extraction capabilities and substantially improving detection performance for small targets like minute defects.

The coordinated operation of these modules—preserving fine-grained features (NAPConv), enabling adaptive feature extraction (novel dynamic convolutions), and enhancing nonlinear representation (KAN)—constitutes our core innovation. This holistic architectural refinement, validated through preliminary tests, effectively improves oil seal defect detection accuracy for defects including tiny scratches, bubbles, and deformations while maintaining real-time performance. Additionally, we introduce an adaptive defect evaluation metric that quantitatively scores different defects to reduce false-positive and false-negative rates.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the developmental context of key technologies.

Section 3 discusses existing achievements in related fields.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and ablation studies. Finally,

Section 5 and

Section 6 provide the conclusions of the paper, elaborating on the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed method and outlining directions for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Technological Evolution of Industrial Defect Detection

Early machine vision systems for defect detection relied on traditional image processing techniques, in which inspection was achieved by manually extracting features such as edges, shapes, and textures [

17,

18]. While offering basic efficiency, these methods were constrained by bottlenecks related to manual design, making it difficult to achieve performance breakthroughs. In the medium term, the rise of machine learning has injected new momentum into the field, with algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs) being representative examples [

19,

20]. In recent years, the development of deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has revolutionized visual defect detection, leading to groundbreaking progress [

21,

22,

23,

24].

2.2. Key Technologies for Real-Time Object Detection

In industrial inspection scenarios, achieving high-speed inference while maintaining high accuracy is crucial for practical deployment. In recent years, several representative technologies have emerged:

Structural reparameterization: Exemplified by RepVGG [

25], this technique enhances feature extraction by employing multibranch convolutions during training and then fusing them into a single-path architecture during inference. This effectively improves inference speed and reduces deployment difficulty.

- (1)

End-to-end detection transformers: Models such as the real-time detection transformer (RT-DETR) [

26] combine dynamic attention mechanisms with dynamic resolution training. This enables low-latency, end-to-end detection without the need for nonmaximum suppression (NMS).

- (2)

Improved Convolution: Improved Convolution encompasses a range of techniques designed to achieve structural efficiency and lightness. A representative example is Partial Convolution (PConv) [

27], which curbs computational cost by processing only a fraction of input channels, thereby optimizing the model for resource-constrained environments.

In summary, existing research has provided a variety of effective and proven paradigms for the design of real-time detection frameworks. By drawing inspiration from these approaches and leveraging insights from prior work, in this study, we aim to construct an efficient architecture that is more sensitive to minute defects, specifically addressing the challenge of capturing subtle defects during oil seal inspection.

3. Methods

3.1. Quality Assessment Algorithm

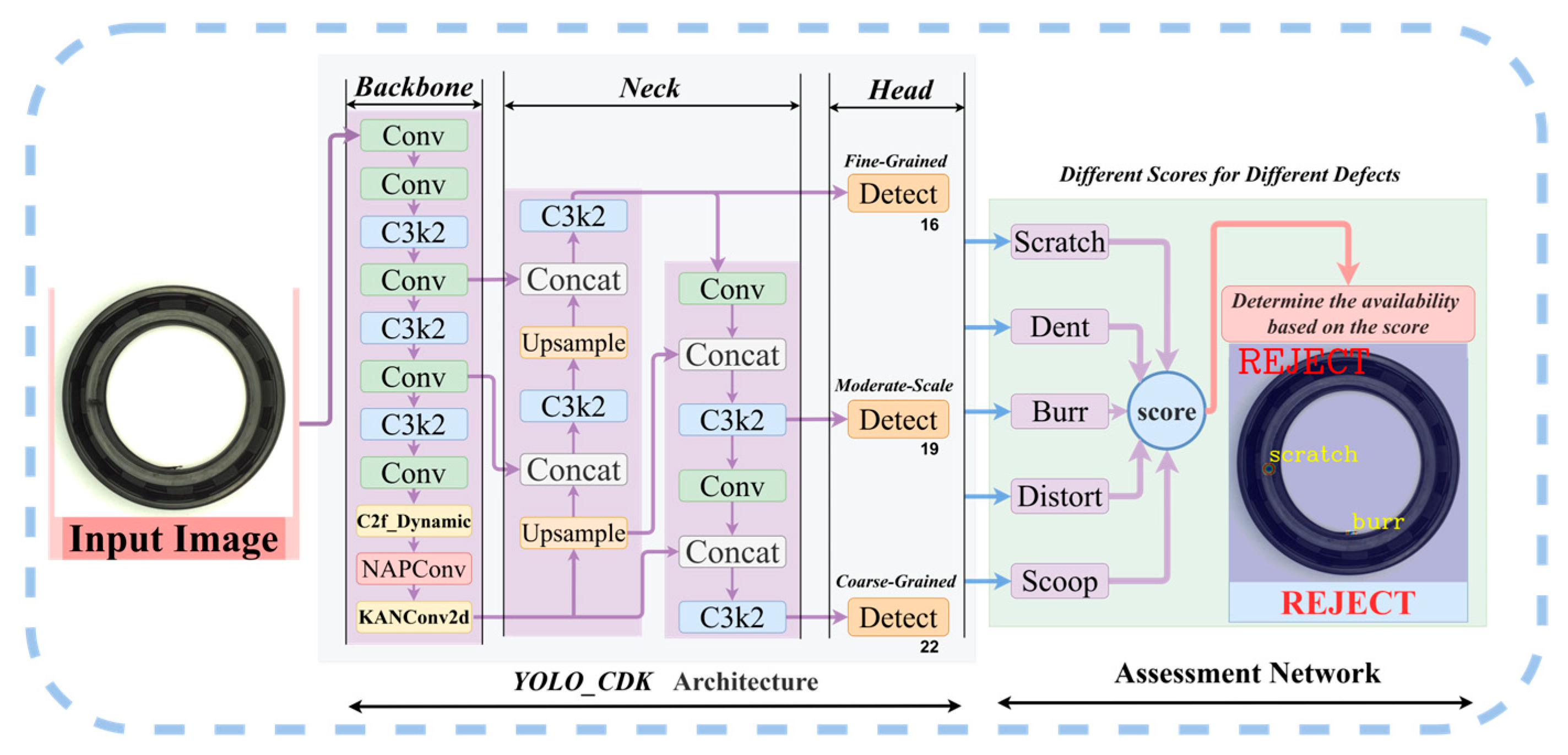

The overall workflow of the proposed algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 1. The system first captures an initial image of an oil seal and inputs it into the enhanced YOLOv11n network for processing. This network extracts multiscale features from the image and computes key target elements related to oil seal defects, including parameters such as defect type, size, and distribution. On the basis of these features, different oil seal samples are subsequently assessed with a defect severity score. Finally, each oil seal’s qualification status is determined by comparing this score against a predefined threshold, thereby achieving automated quality sorting.

The target defects detected in this study are categorized into five classes: Dent, Burr, Distortion, Scratch, and Scoop. The defect scoring rules are established as follows:

Rule 1: Oil seals shall be directly deemed nonconforming products upon detection of any defects categorized as Distortion, Scoop, or Dent.

Rule 2: For defects classified as Burr or Scratch, points shall be accumulated based on their actual occupied area and corresponding weight coefficients.

From Rules 1 and 2, the base score B for a single defect is given by:

Rule 3: In the absence of any defects categorized as Distortion, Scoop, or Dent, all scores of the remaining defects shall be weighted and aggregated into a final composite score

F. If

F is greater than the threshold

(where

is determined via statistical experimental methods based on the specific material of the oil seal, with slight variations across different materials), this result reflects the presence of unacceptable wear and deformation generated during the production process. Such oil seals fail to meet the quality requirements and do not comply with the relevant provisions of the international core standard for oil seals, ISO 6194-1:2007 [

28]. Therefore, they shall be deemed nonconforming products. The formula is as follows:

3.2. Data Augmentation

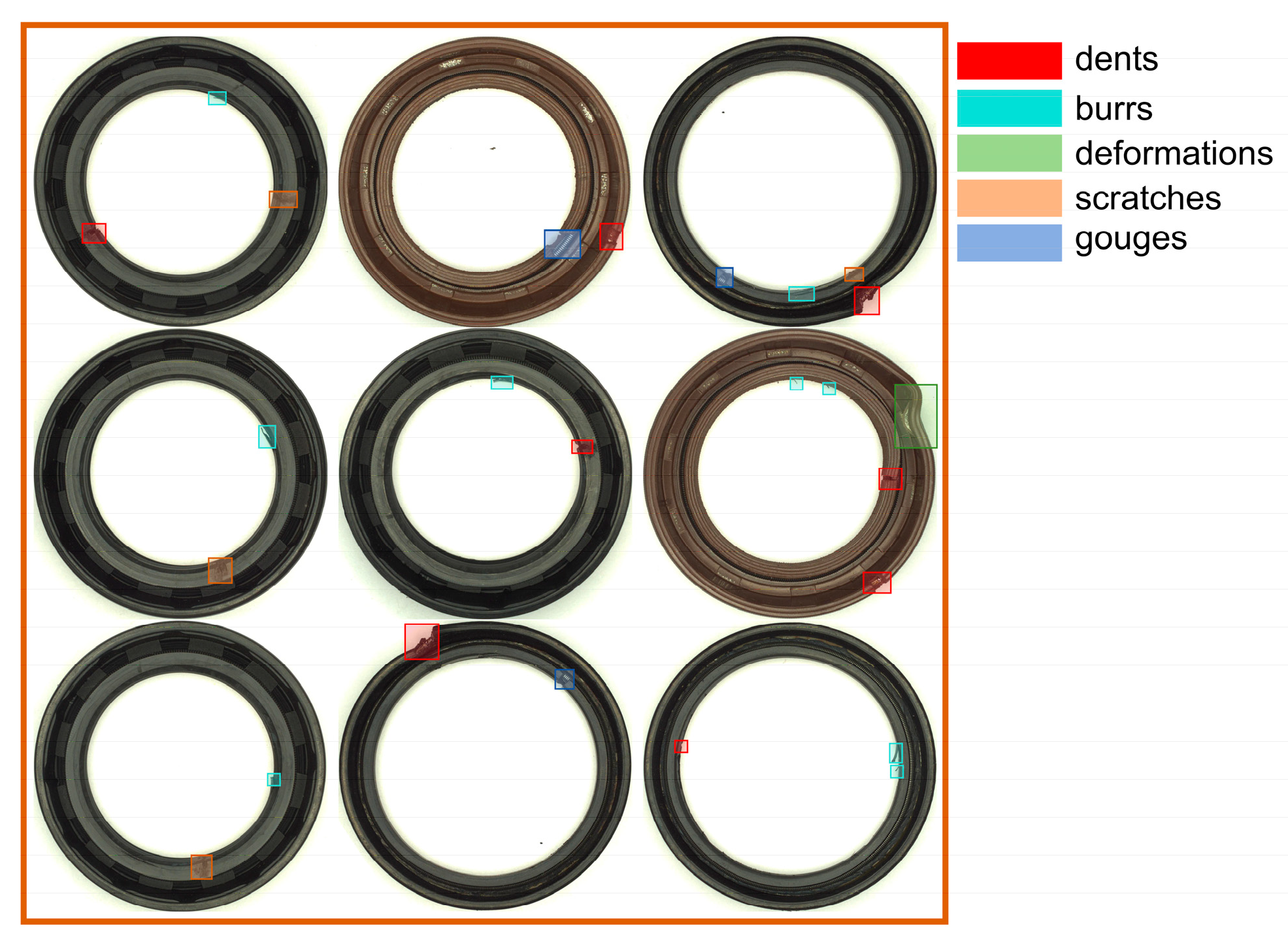

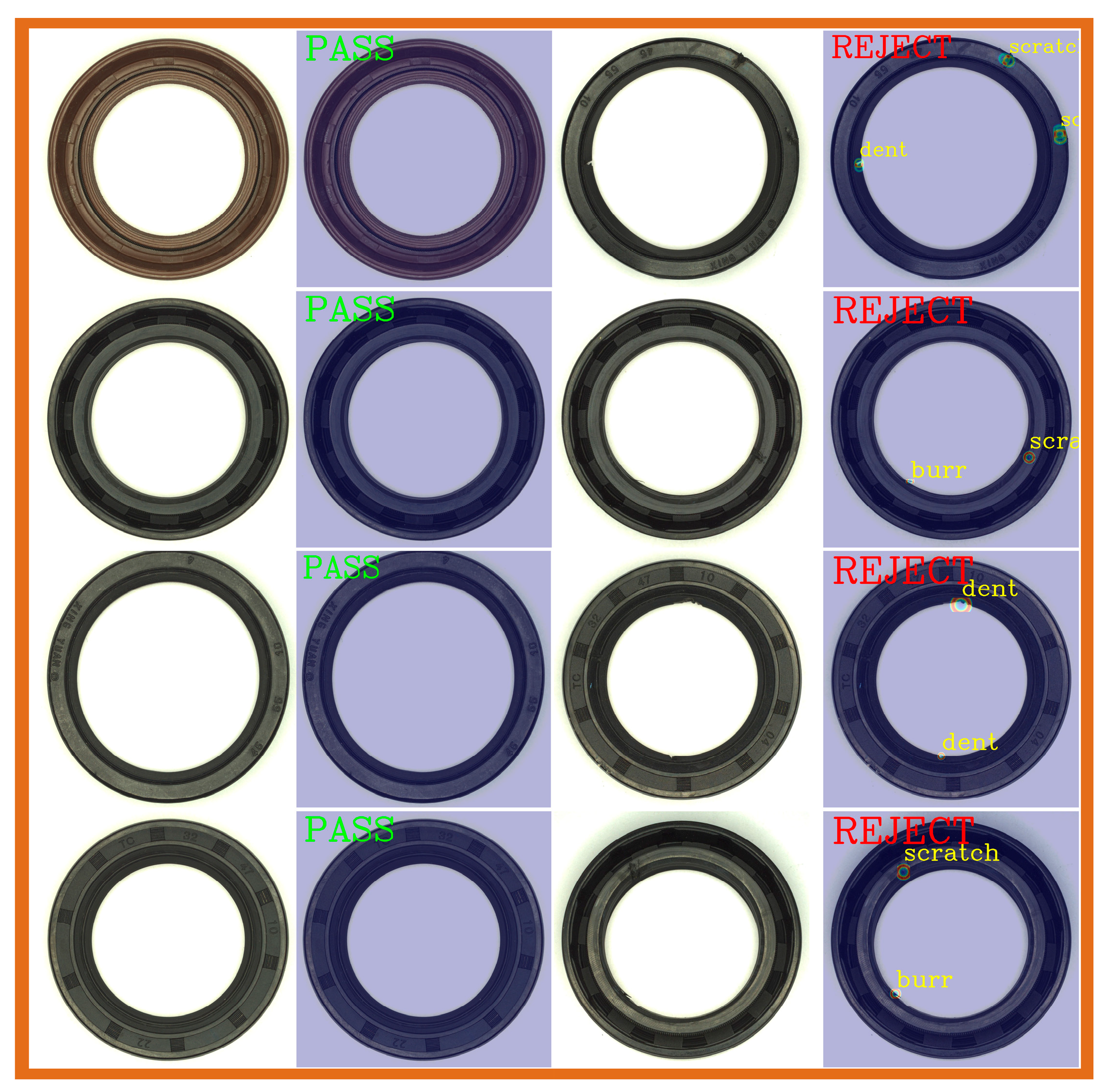

The oil seal samples used in this study were sourced from two manufacturers: Fulingbeike Sealing Components (Kunshan) Co., Ltd. (Kunshan, China), and FANUC Corporation (Yamanashi, Japan). The samples comprised two models with dimensions of 32 × 47 × 10 and 45 × 55 × 10, as shown in

Figure 2. The materials included nitrile rubber (NBR) and fluoroelastomer (FKM) oil seals. A total of 2000 RGB images were captured using a Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) 6-megapixel professional camera under varying angles and lighting conditions. Among these, approximately 1400 images were used as the training set, and approximately 600 were used as the validation set. Each global image contained annotations for 2 to 4 defects, whereas each close-up detail image contained annotations for 1 to 2 defects. All the images were manually annotated, endowing the dataset with advantages in terms of scale diversity and defect variety.

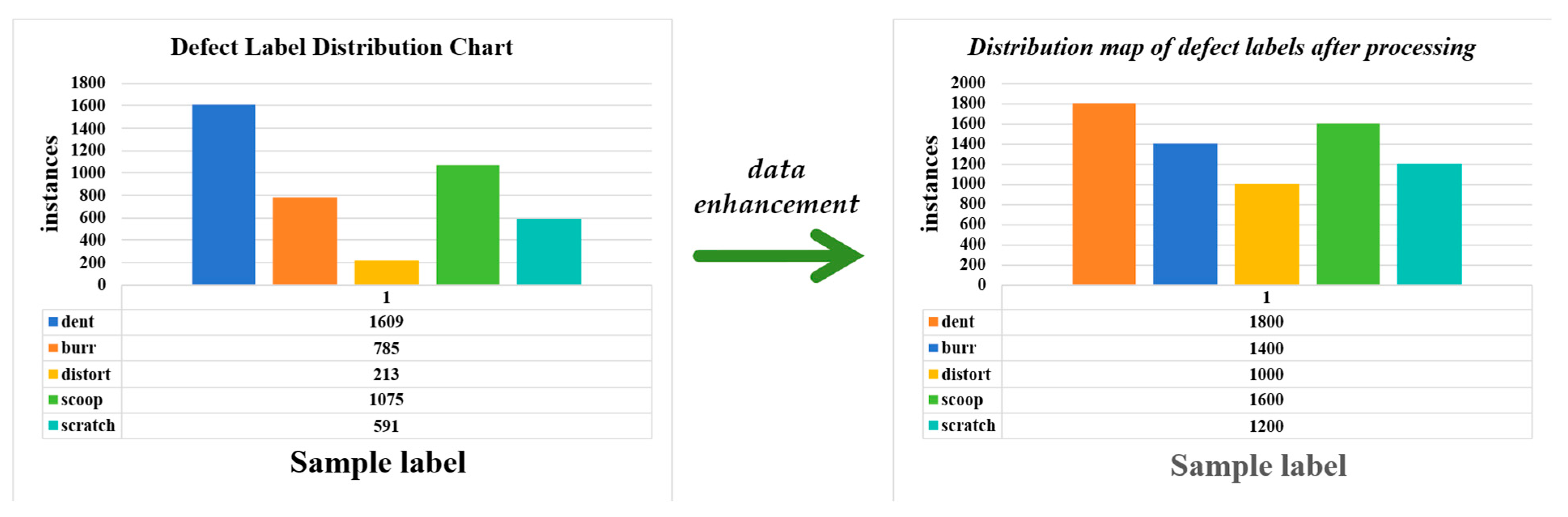

To enhance the robustness and generalizability of the model, we adopted a comprehensive data augmentation strategy [

29]. To address the significant distribution shifts caused by varying sample frequencies and collection difficulties across categories, we applied differentiated data augmentation intensities to the original dataset. This approach effectively mitigates disparities arising from imbalanced sample sizes, as illustrated in

Figure 3. At the image level, Gaussian blur was introduced, and brightness, saturation, and color space were randomly adjusted to simulate lighting variations. At the geometric level, perspective transformation and random rotation were applied to emulate diverse viewing angles and aspect ratios of targets. Furthermore, random occlusion—filling random rectangular regions with specific grayscale values or noise—was incorporated to simulate complex scenarios where targets are partially obscured or subjected to interference, thereby strengthening the model’s anti-interference capability and robustness.

3.3. Improved Algorithm Model Design

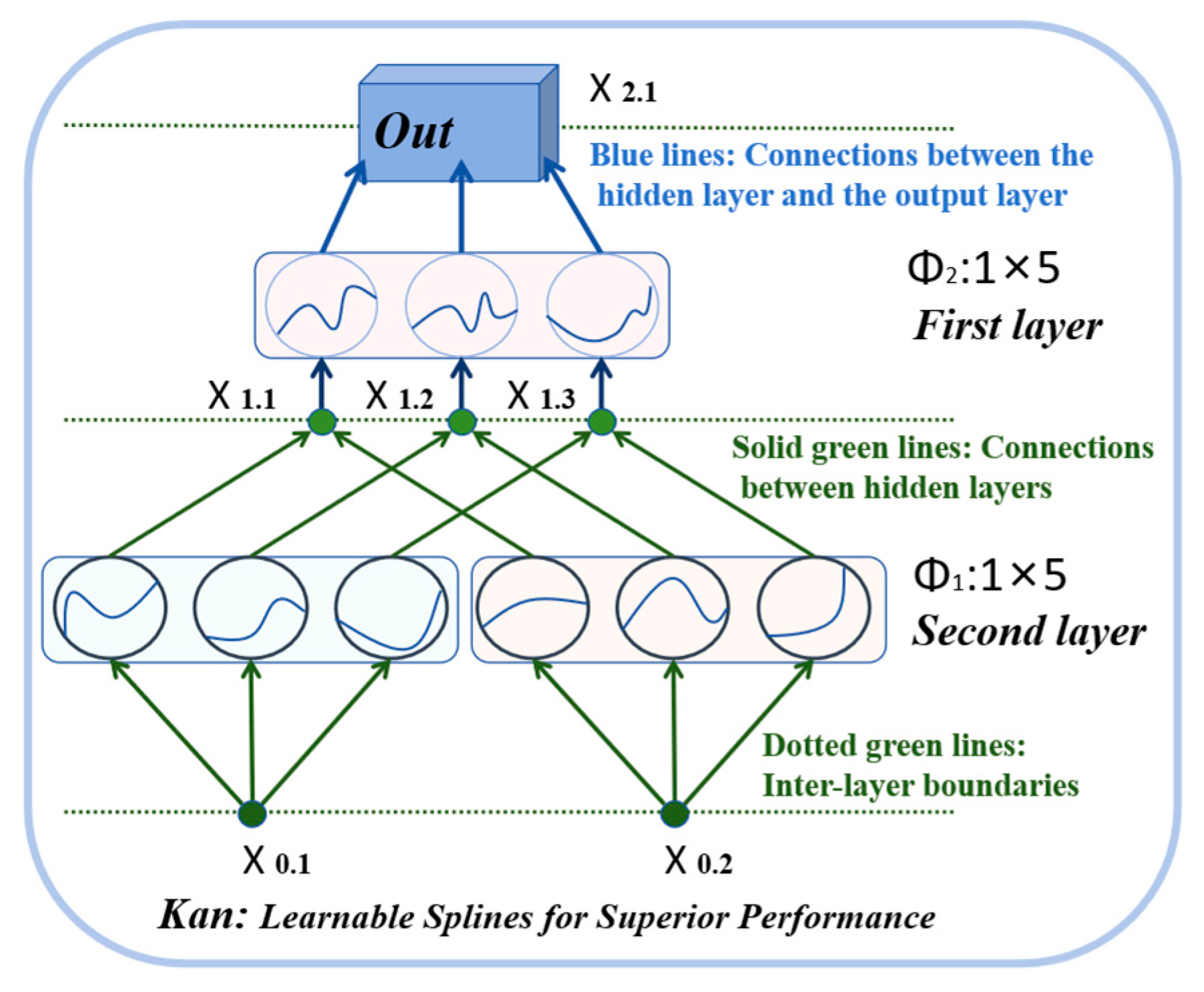

3.3.1. KANConv2d Module

Since the C2PSA structure in the YOLOv11n backbone network is based on an attention mechanism, its computational complexity increases quadratically, leading to excessively long computation times in edge detection environments and difficulty meeting real-time requirements. Defects such as minute black wear and burrs on oil seal surfaces are extremely small in scale and exhibit weak features, making them challenging to capture effectively with existing methods. To address these issues while balancing computational complexity and detection accuracy, we propose integrating an improved 3rd-order KANConv2d network into the YOLOv11n algorithm, leveraging the powerful nonlinear fitting capability of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs). Unlike traditional nonlinear feature extractors such as MLP-Mixer and SIREN, KANs are grounded in the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem, approximating complex functions through linear combinations of learnable univariate spline basis functions (a simplified schematic of this principle is shown in

Figure 4. This unique architecture endows KANs with three key advantages:

- (1)

superior parameter efficiency

KANs achieve comparable or higher fitting accuracy with significantly fewer parameters than MLP-Mixer (which suffers from parameter redundancy due to its linear-weight-based design) and SIREN (which incurs high computational overhead from sinusoidal activation);

- (2)

enhanced representational flexibility

Unlike SIREN’s reliance on fixed periodic sinusoidal activation (limiting its adaptability to non-periodic defect features), KANs’ learnable spline basis functions can model arbitrary nonlinear relationships, enabling more precise capture of weak and tiny defect features;

- (3)

computational efficiency

KANs avoid the quadratic complexity of attention mechanisms and the high arithmetic cost of SIREN, making them more suitable for edge deployment. Through end-to-end learning, KANConv2d concentrates adaptively on tiny defect regions, addressing the trade-off between real-time performance and detection accuracy that plagues existing methods.

3.3.2. NAPConv Module

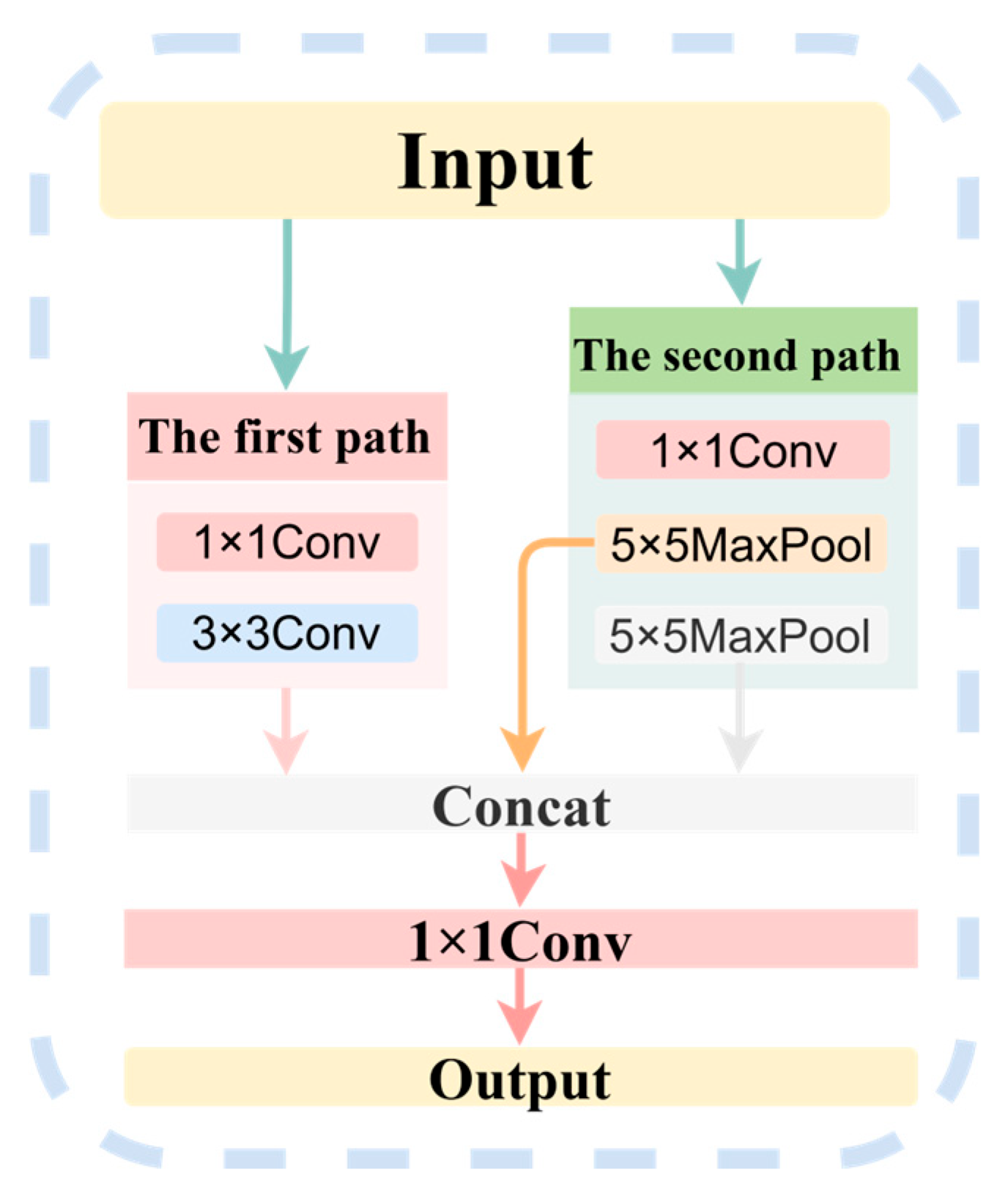

The NAPConv module, illustrated in

Figure 5, is architected around two core principles: an efficient channel dimension management strategy and a heterogeneous multi-path feature extraction mechanism. This dual approach achieves a lightweight design while enhancing the network’s capacity for multi-scale feature integration, thereby effectively accommodating the significant feature heterogeneity inherent to oil seal defects—from small, localized imperfections like dents and burrs to larger, more extensive deformations.

- (1)

Channel Dimension Management Strategy

To curb computational complexity in subsequent processing stages, the module first employs 1 × 1 convolutions to reduce the channel dimensions to 1/4 and 1/2 of the input, respectively. This serves a dual purpose: it is a fundamental step in constructing a lightweight architecture, and it acts as an information bottleneck, forcing the compression and retention of the most critical feature information. This strategic reduction in dimensionality allocates the necessary computational budget for the subsequent incorporation of large-kernel operations, such as 5 × 5 pooling.

- (2)

Construction of the Heterogeneous Multi-Path Feature Extraction Module

This module leverages two distinct paths designed to capture complementary features aligned with different defect characteristics:

Path 1 (Local Fine Feature Path): This path employs a series of 3 × 3 convolutional layers for in-depth spatial feature extraction on the dimension-reduced input. This configuration is specifically designed to capture high-frequency spatial patterns and localized texture details, which are critical for identifying subtle, small-area defects such as dents and burrs. The preservation of high-resolution feature maps throughout this path ensures the precise localization and characterization of such fine-grained anomalies.

Path 2 (High-level Receptive Field Path): In contrast, this branch prioritizes the efficient expansion of the receptive field. It first utilizes 1 × 1 convolutions to model cross-channel dependencies and condense the feature representation. This is followed by two successive 5 × 5 max pooling layers, which systematically abstract larger spatial contexts and enhance salient features while suppressing irrelevant noise. This design yields a feature map rich in semantic information and global context, which is crucial for diagnosing large-area defects such as deformations, as their effective recognition hinges on the perception of overall structural distortions rather than on localized fine-scale textures or color anomalies.

Feature Fusion: The outputs from these two structurally heterogeneous paths are then concatenated and fused through a 1 × 1 convolution. This diversified multi-scale fusion strategy synergistically integrates complementary information: the fine-grained details from Path 1 and the coarse-grained semantic context from Path 2. Consequently, it generates a more robust and discriminative composite representation, effectively mitigating the feature redundancy often encountered in homogeneous-scale fusion approaches.

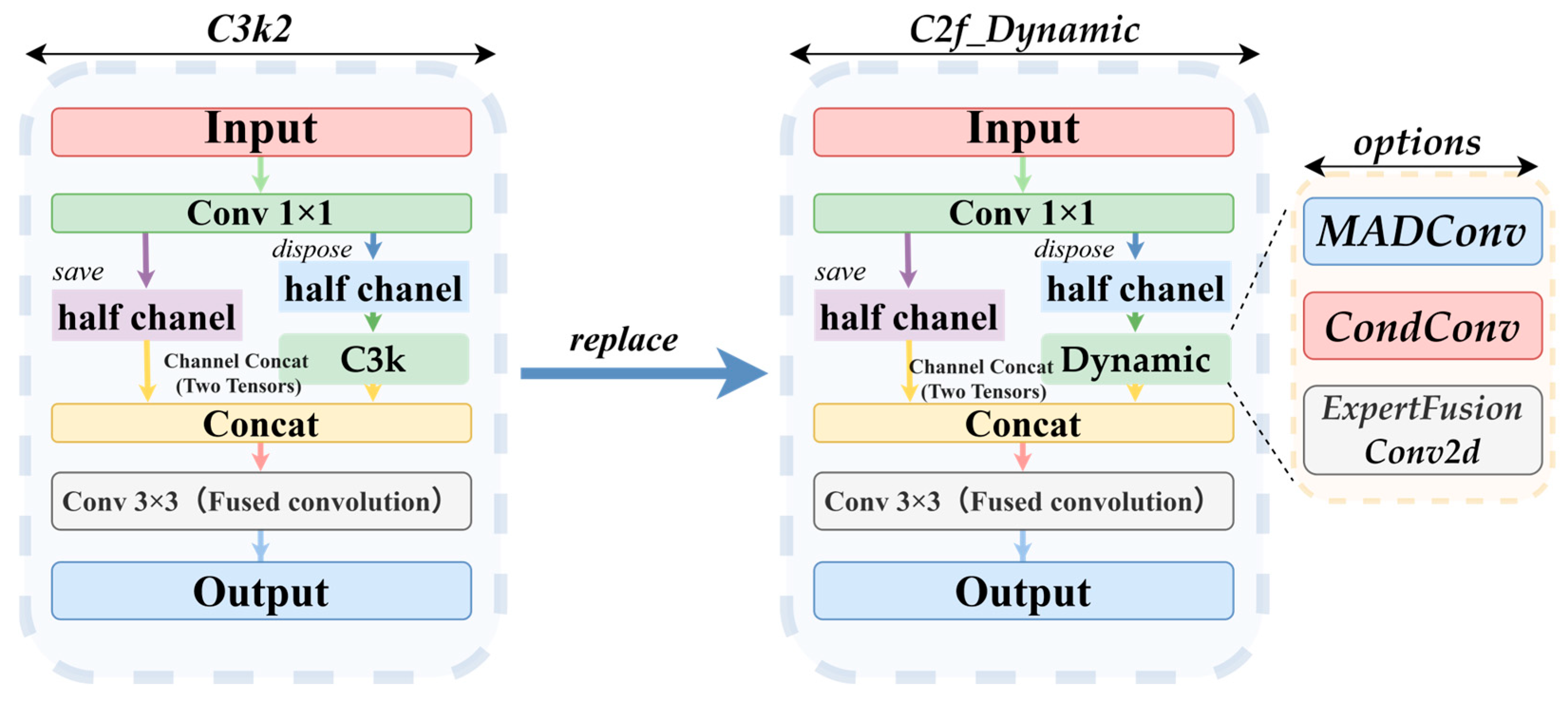

3.3.3. C2f_Dynamic Module

The core idea of the proposed C2f_Dynamic module is to optimize the traditional C3K2 module (

Figure 6) by introducing convolutions with dynamically generated parameters and input-dependent adaptation. In this module, the convolution kernels are no longer fixed; instead, their weights are generated in real time or formed via dynamic weighted fusion by a lightweight subnetwork based on the input feature maps. This enables the kernel parameters to flexibly adjust according to the input content. This design enhances the model’s perception of fine details in minor defects and allows it to dynamically adjust its feature extraction strategy on the basis of the characteristics of different defects. This significantly improves the model’s generalization ability and accuracy in complex multiscale, multicategory defect detection tasks. In this paper, three distinct dynamic convolution variants are designed: MADConv, CondConv, and ExpertFusionConv2d. These variants are analyzed individually in

Section 3.3.4,

Section 3.3.5 and

Section 3.3.6 3.3.4. MADConv Module

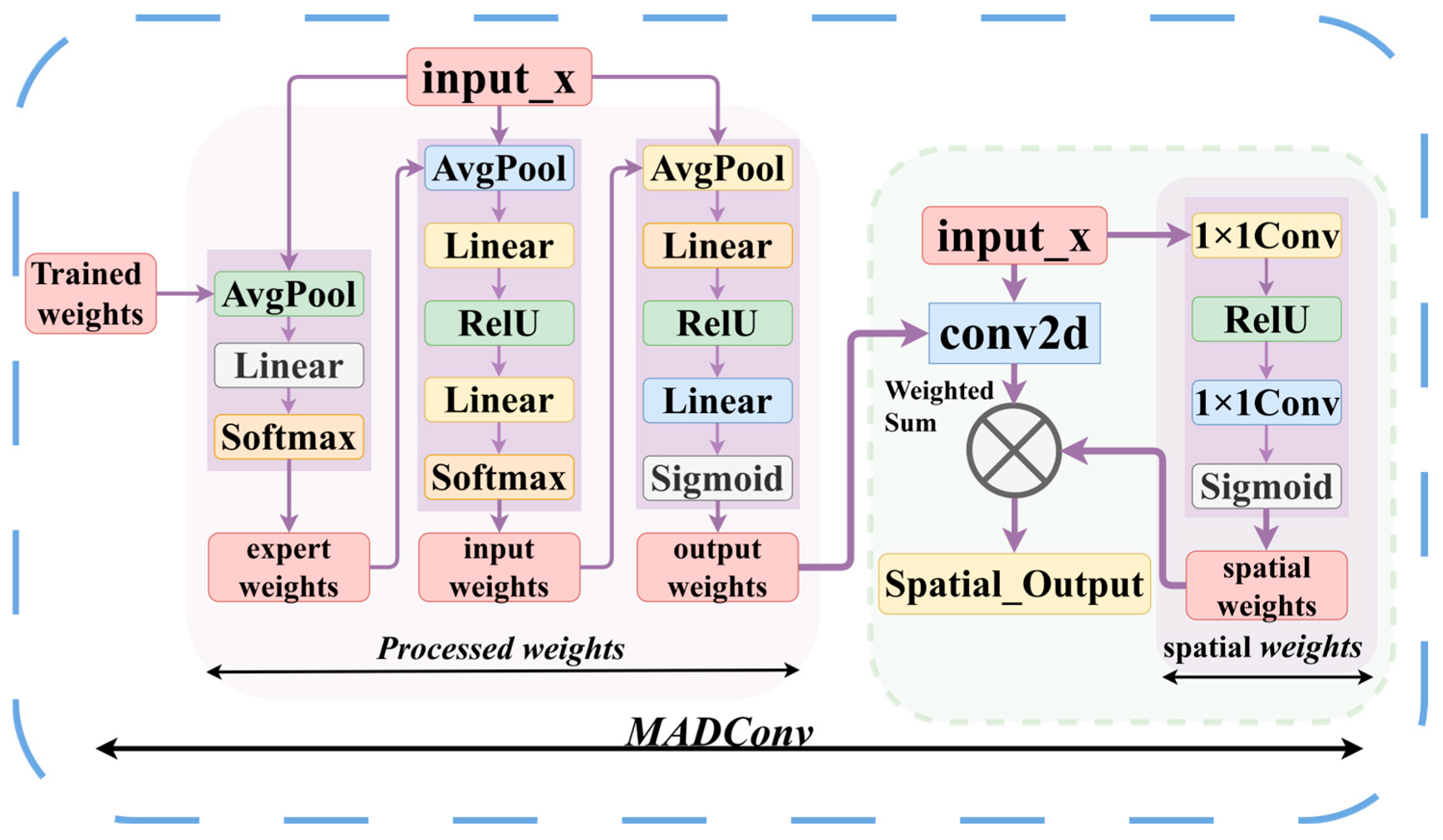

MADConv performs dynamic feature modulation through four sequential attention mechanisms:

Expert Attention: Fuses multiple convolutional kernels using input-dependent weights.

Input Attention: Simultaneously recalibrates both input and output channel dimensions.

Output Processing: Executes independent convolution for each sample via reshaped group convolution.

Spatial Attention: Enhances feature importance across spatial dimensions.

This structured approach enables efficient, input-adaptive convolution across four complementary dimensions, balancing representation power with computational practicality as illustrated in

Figure 7.

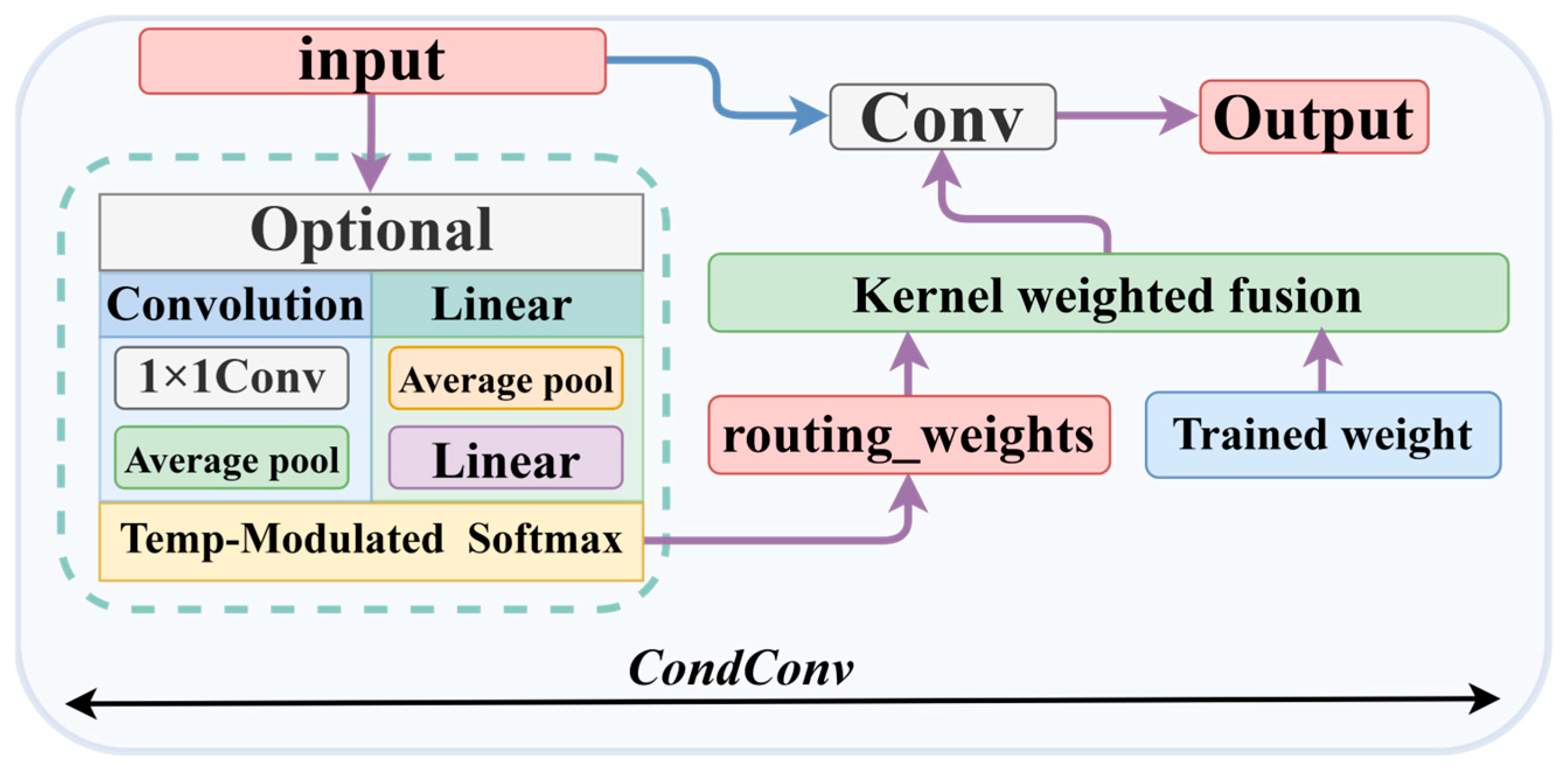

3.3.5. CondConv Module

Inspired by CondConv, this module incorporates a lightweight routing network that dynamically generates convolution weights based on the input image. This allows multiple expert convolution kernels to be adaptively fused into one dedicated set of kernels.

Compared to conventional designs, our improved scheme introduces the following key features:

- (1)

It provides the choice between a convolution-based and a fully connected routing strategy to capture features at different granularities.

- (2)

We replace the traditional sigmoid activation with softmax and introduce a tunable temperature parameter to control the smoothness of the routing weight distribution. This parameter can be adjusted according to the target application. Through extensive preliminary experiments, we set its default value to 0.4. This design enables flexible and dynamic adaptation of the model’s behavior across various scenarios.

- (3)

A number of engineering optimizations are applied, such as grouped convolution implementation, memory layout optimization, and support for mixed-precision and quantization. We also experimentally determine the optimal combination pattern and structural placement of the module. The overall structure is illustrated in

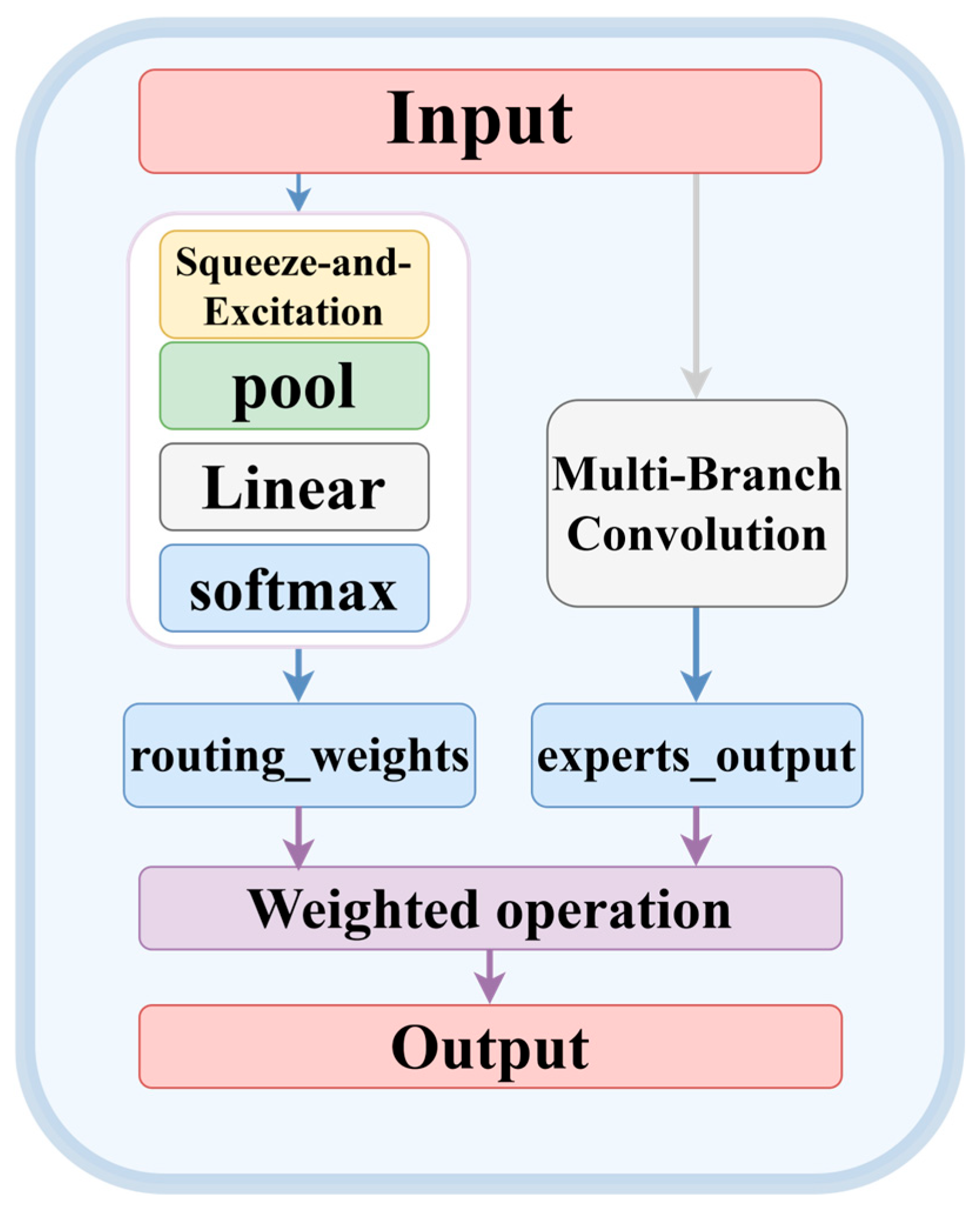

Figure 8.

3.3.6. ExpertFusionConv2d Module

This module adopts a distinct output-fusion strategy, contrasting with CondConv2d’s pre-fusion approach, through the following operational sequence:

Parallel Expert Processing: Executes convolution operations independently and in parallel using all expert kernels.

Output Fusion: Dynamically aggregates the outputs from each expert using attention-derived routing weights.

Independent Expert Bias: Employs dedicated bias parameters for each expert, enhancing representational capacity.

This design inherently improves model interpretability by preserving and making visible the activation patterns of individual experts, thereby providing explicit guidance for subsequent model analysis and refinement. The architecture is detailed in

Figure 9.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

Model training was conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Laptop GPU, with comparative experiments including both DETR [

30] and Faster R-CNN [

31] as benchmark classical architectures. Deployment testing of the optimized model was subsequently performed on a Jetson Nano platform to validate its performance in practical application scenarios. The specific hyperparameter configurations used during the model training phase are detailed in

Table 1.

Furthermore, to ensure a fair performance comparison across different networks, pretrained weights were not utilized. For the C2f_Dynamic module, the number of experts was set to 4. The dgrid_size and spline_order parameters of the KANConv2d module were both set to 3.

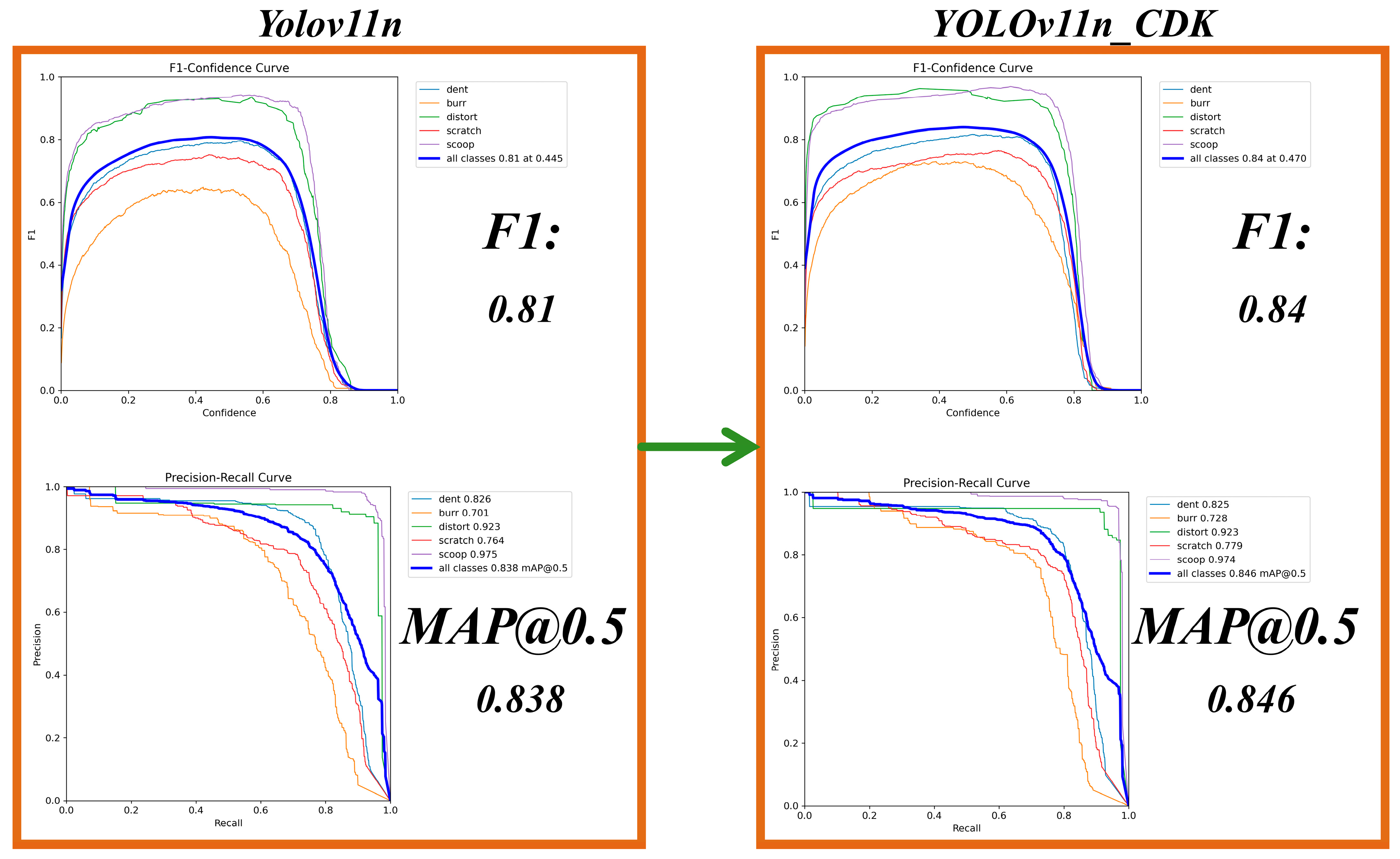

The mean Average Precision (mAP) and the F1 score are adopted as the primary evaluation metrics. Specifically, we report the mAP at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 50% (i.e., mAP@0.5), as well as the maximum F1 score, which reflects the balance between precision and recall.

4.2. Experimentation

4.2.1. Selection of the Basic Network

In this study, modules from YOLOv10n to YOLOv13n and YOLOv10s were selected and compared, and the specific results are detailed in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, while YOLOv11s achieves the highest accuracy among the compared models, its substantial computational cost and large parameter count render it unsuitable for edge deployment. Similarly, both Faster R-CNN and DETR exhibit prohibitively high computational complexity and parameter counts that far exceed practical deployment constraints. Furthermore, these traditional computer vision architectures (such as Faster R-CNN and DETR) fail to demonstrate compensating advantages in detection accuracy for our specific application scenario, with their performance levels falling short of practical requirements. Among the remaining models, YOLOv11n delivers the most favorable performance trade-off, and was therefore selected as the final baseline model.

4.2.2. Adaptation Experiment for Different Versions of C2f_Dynamic

The experiments involved testing and comparisons across several key factors: core variable settings, bottleneck structure variations, and residual connection variations.

Core variable: Three distinct structures—MADConv, CondConv, and ExpertFusionConv2d—along with their different variants, were compared as replacements. Their accuracy, computational complexity, and parameter count were tested, respectively.

- (1)

Bottleneck structure variation: This evaluated the impact of introducing a two-layer bottleneck network (denoted by ‘_B’) into the dynamic convolution and compared it against the standard structure.

- (2)

Residual connection variation: This involved adding residual connections (denoted by ‘_R’) to the dynamic convolution and comparing it with the base version, which lacks such connections. The specific structural configurations are provided in

Table 3.

The introduction of dynamic convolutions generally led to improvements in accuracy metrics such as the F1 score and mAP@0.5, confirming the value of this approach. However, contradicting the conventional belief that “a two-layer structure outperforms a single-layer structure,” the experimental results clearly showed that two-layer dynamic convolution achieved significantly lower accuracy than its single-layer counterpart did. We attribute this to two main reasons. First, multilayer stacking causes an overprojection of the feature space, diluting or interfering with the critical patterns already captured by a single layer and introducing redundant computations. Second, as the network deepens, the dynamic allocation mechanism for expert weights struggles to adapt to more complex feature distribution, leading to decreased efficiency in interlayer feature transformation. Consequently, the model has difficulty converging to a superior solution under limited training resources.

Among the three dynamic convolution structures tested, the introduction of residual connections resulted in performance gains for some models. This indicates relative compatibility between residual connections and the ExpertFusionConv2d architecture. Considering the performance comparison across all experimental schemes, the single-layer ExpertFusionConv2d module with residual connections was ultimately selected.

4.2.3. Ablation Experiments

Ablation studies (

Table 4) reveal distinct module contributions and their synergies. Individually, KANConv2d provided the most significant mAP@0.5 gain (+1.5%), confirming its strength in nonlinear feature transformation. C2f_Dynamic reduced computational costs (GFLOPs: 6.2) while maintaining competitive accuracy, demonstrating efficient dynamic feature extraction. NAPConv improved feature preservation, reflected in its balanced F1-score (0.82).

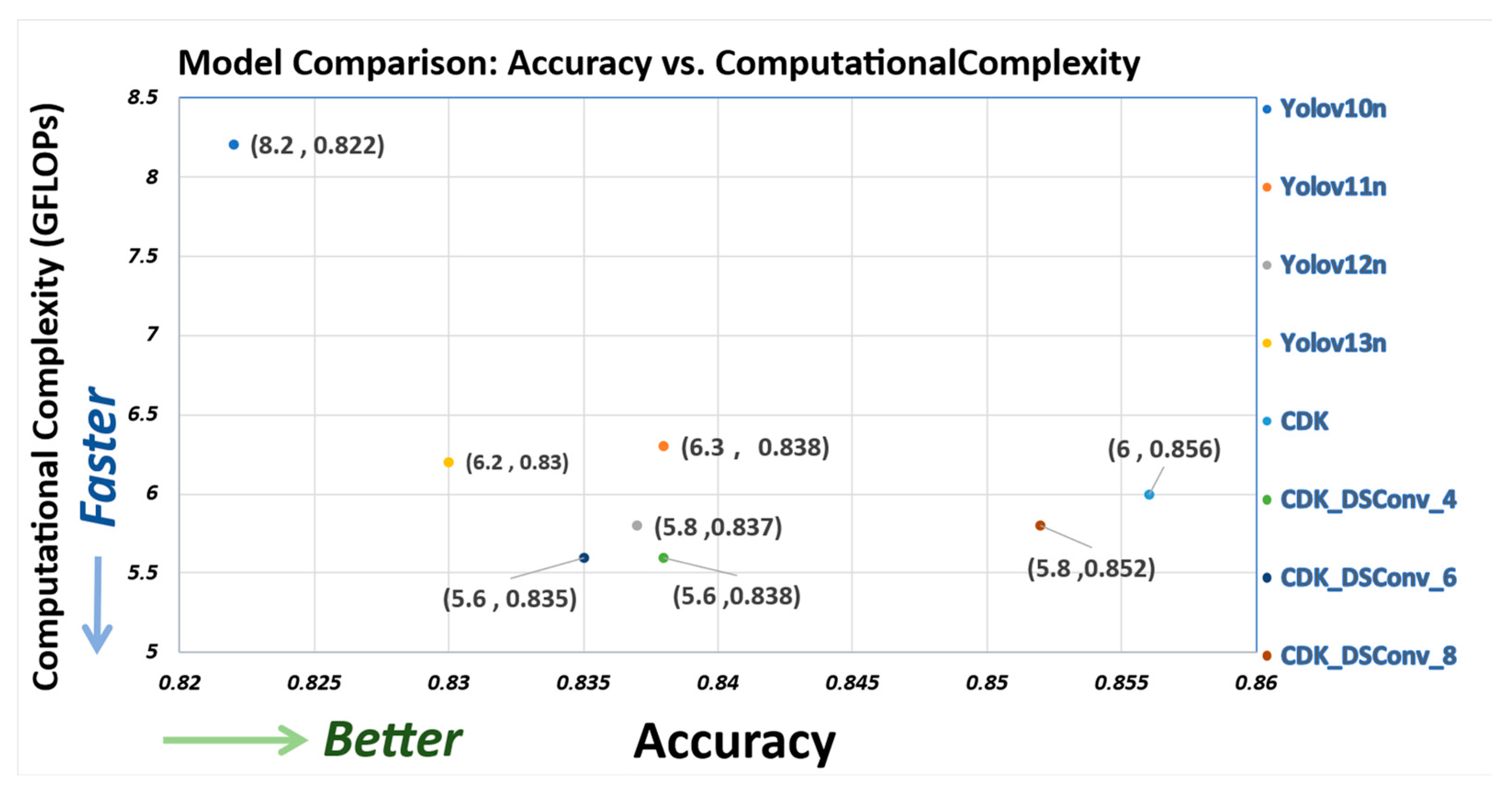

Critically, the full integration (YOLOv11n_CDK) achieved a synergistic effect, attaining the highest F1-score (0.84) and mAP@0.5 (0.856) while simultaneously reducing computational cost to the lowest GFLOPs (6.0). This outcome suggests that the complementary strengths of the modules—dynamic filtering, feature preservation, and enhanced representation—collectively enable a more robust and efficient architecture, which, in our experiments, outperformed all evaluated partial combinations.

4.2.4. Experiment on Adding DSConv

The slight increase in the value of the parameters observed in the YOLOv11n_CDK configuration can be attributed to two main factors: first, each expert in the C2f_Dynamic module requires independent weight parameters; second, the parameters of KANLinear increase in a three-dimensional product manner with the grid size. To address this issue, we introduce the depthwise separable convolution (DSConv) [

32] module in an attempt to reduce the number of parameters. The effects of introducing the modules at different positions are shown in

Table 5.

From the experimental results, the CDK_DSConv_6 and CDK_DSConv_8 models demonstrate unique advantages in reducing both the parameter count and computational complexity.

4.2.5. Dual-Path Ablation Experiments on the NAPConv Module

To quantitatively validate the individual contributions of the two heterogeneous paths in the NAPConv module, three experimental groups are designed with all other network architectures, training hyperparameters, and test datasets kept consistent: the Baseline (YOLOv11n_CDK), Ablation Group_1 (removing Path 1 to verify the impact of fine-grained texture information loss on small defect detection), and Ablation Group_2 (removing Path 2 to assess the necessity of global semantic context for large-area defect recognition), with performance discrepancies between groups quantifying the irreplaceability of each path. The performance differences among different ablation groups are shown in

Table 6.

The ablation study on the dual-path mechanism reveals that disabling either path degrades performance, but to differing extents. Removing the 2-channel path, which utilizes large-kernel convolutions to capture macro-level and global features, causes a more pronounced performance drop. In contrast, disabling the 1-channel path—responsible for extracting fine-grained details—results in a relatively smaller decline. This indicates that the large-kernel macro representations provided by the 2-channel path are more critical to overall model performance, while fine-grained features, though useful, play a secondary role. The results confirm the complementary nature of the two feature extraction pathways.

5. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that the integrated architecture, constructed using the single-layer residual ExpertFusionConv2d, NAPConv, and KANConv2d modules, exhibits effective performance synergy for the current oil seal detection task: while it maintains a lightweight computational overhead suitable for edge deployment, it effectively enhances overall detection accuracy.

Furthermore,

Figure 10 presents typical cases of the final detection and identification results of some defects. Specifically, the left side of

Figure 10 shows a normal oil seal, while the right side shows an defective oil seal. The heat map clearly marks the detected defects and their categories. For defective products, the upper left corner clearly indicates that this oil seal is REJECT.

Figure 11 compares the performance of the CDK, CDK_DSConv_6, and CDK_DSConv_8 models in terms of detection accuracy versus computational complexity. In this plot, a larger value on the horizontal axis corresponds to higher accuracy, and a smaller value on the vertical axis indicates lower complexity (and thus higher efficiency). The CDK model and its variants achieve high scores on the accuracy axis, confirming their superior detection performance. They also score well on the efficiency axis, outperforming the Yolov10n benchmark and demonstrating their practicality for real-world applications.

Figure 12 shows the performance improvements in the F1-score (top) and mAP@50 (bottom). The most significant gain was in the detection of burr defects. Specifically, at a confidence threshold of 0.4, the precision for burr detection rose from approximately 0.61 to 0.65. This improvement enhanced the model’s ability to detect small targets, which was a major factor in the overall performance gain.

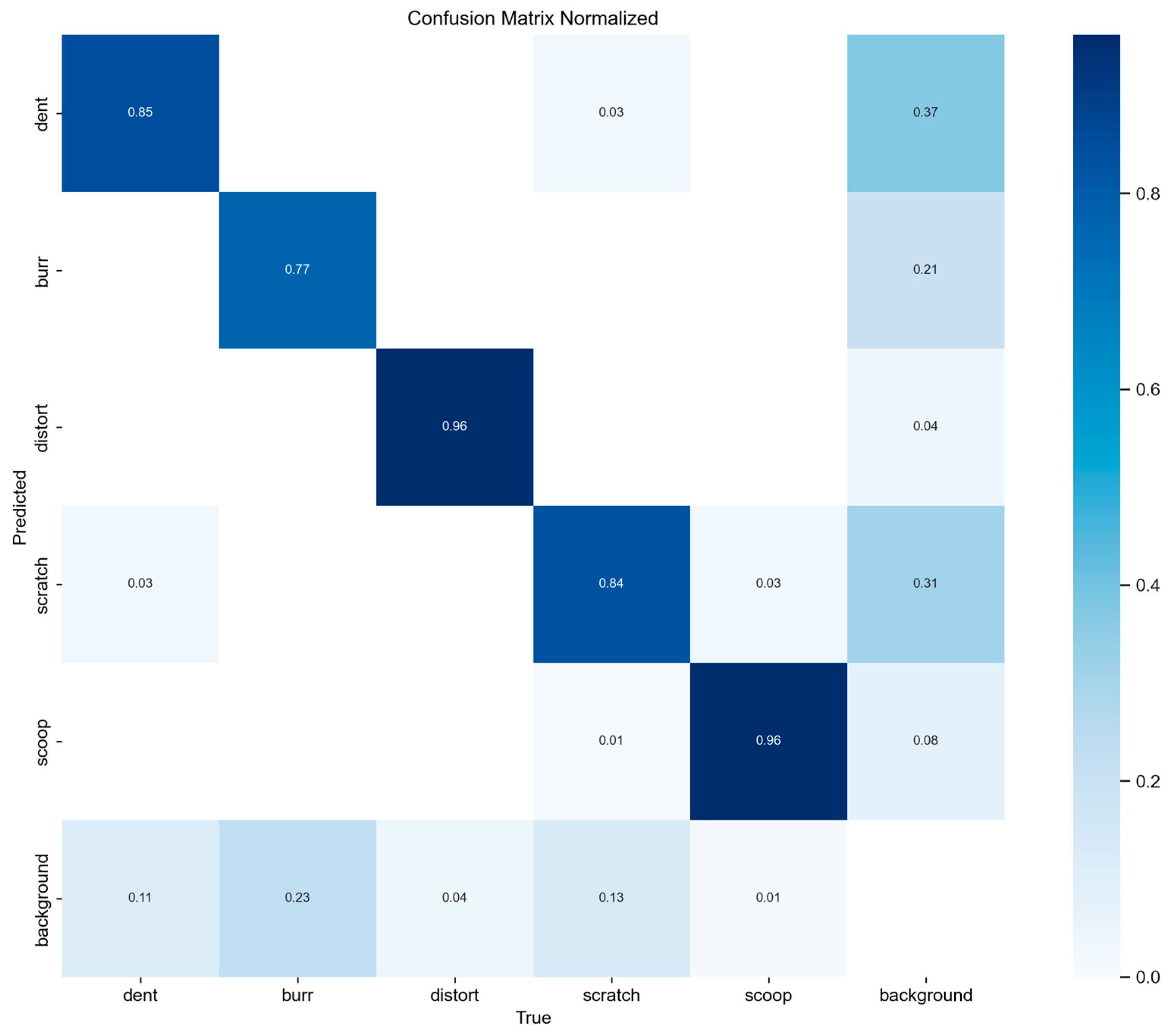

As shown in the confusion matrix (

Figure 13), the YOLOv11n_CDK model maintains high overall accuracy but faces a clear challenge with specific defect types. The primary limitation is the reliable detection of dents and burrs, which, being generally small and indistinct, are frequently confused with the background; this inherent difficulty is a key obstacle to further improvement.

As shown in

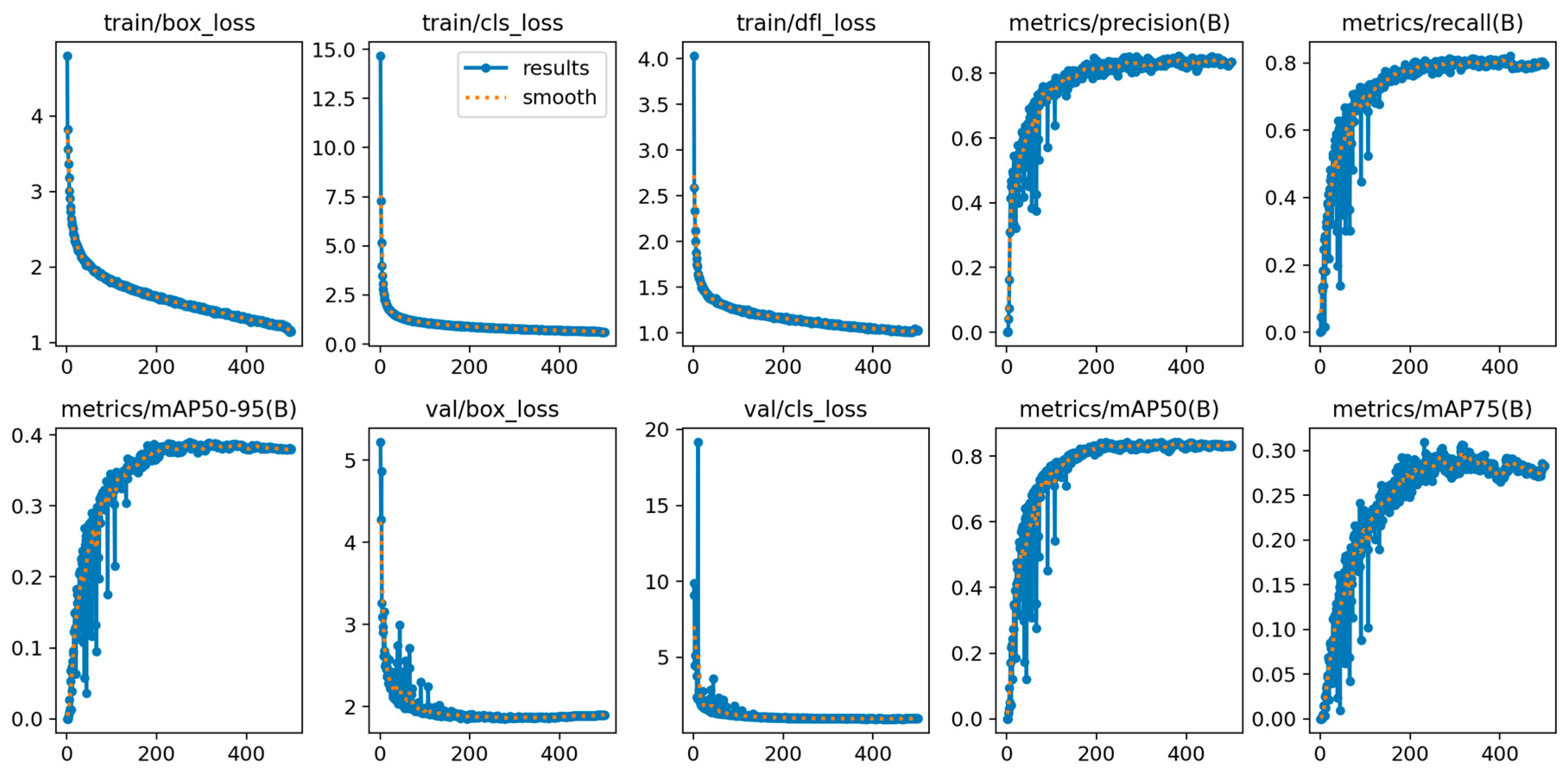

Figure 14, this figure presents the training and validation curves of the proposed model. Training losses (box_loss, cls_loss, dfl_loss) decrease rapidly and stably, converging to low levels with minimal fluctuations. Validation losses (val_box_loss, val_cls_loss) follow a consistent trend, while training metrics (precision, recall, mAP) rise sharply in early epochs and stabilize at high values. These results fully reflect the model’s excellent convergence performance and strong adaptability to the target dataset.

6. Conclusions

In the current field of industrial oil seal quality inspection, numerous visual detection methods have been proposed. However, achieving an optimal balance between real-time performance and detection accuracy remains challenging, primarily because of the intrinsic feature sparsity of oil seals. To address this issue, we propose an enhanced architecture based on YOLOv11n. The core contributions are threefold. First, we propose a backbone optimization strategy that involves replacing the C3K2 module at the 9th layer with a novel, more powerful single-layer residual dynamic convolution named ExpertFusionConv2d. Second, we introduce the NAPConv module for enhanced multifeature extraction and fusion. Third, a new KANConv2d module is employed at the 11th layer to bolster the model’s capacity for capturing complex features.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, comprehensive experiments were conducted on a dedicated oil seal inspection dataset. The results demonstrate that our optimized model achieves a significant performance gain while maintaining high inference efficiency. Specifically, the mAP@0.5 score increased from 0.838 (baseline) to 0.856, and the computational cost was reduced from 6.3 GFLOPs to 6.0 GFLOPs. When deployed on a Jetson Nano embedded system, the model processes a single image in approximately 6.3 milliseconds, achieving a frame rate of 105-110 FPS. These results collectively indicate that our approach successfully balances detection accuracy with operational speed, making it suitable for real-time industrial inspection scenarios.

However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the current model is specifically adapted for the sequential inspection of a single, standard-shaped oil seal and has not yet been fully optimized for scenarios involving non-standard seal geometries or the simultaneous detection of multiple seals. Secondly, the system lacks integrated functionality for the precise measurement of key seal dimensions, focusing solely on defect identification.

Future efforts will be directed towards addressing these limitations through the following research avenues:

Developing simultaneous quality compliance assessment for multiple oil seals by integrating defect detection with instance localization.

Incorporating multisensor technologies (e.g., laser measurement) to develop a fully intelligent inspection system that integrates defect identification with parameter measurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and X.C.; methodology, Y.C. and Y.W.; software, X.W. and Y.W.; validation, Y.C. and W.H.; formal analysis, X.W. and W.H.; investigation, Y.C. and G.H.; resources, X.C.; data curation, X.W. and G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, X.W.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Advanced Manufacturing Industry “Jiebang Guashuai” Project (No. 2025GXZH003), the Hunan Innovative Province Construction Special Project (No. 2025QK2005), and the Regional Joint Fund of Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2025JJ70615).

Data Availability Statement

The oil seal image dataset used to support the findings of this study was captured by the authors and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The main code can be accessed from GitHub:

https://github.com/iMoonLab/yolov13 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

Thanks are also extended to the “Beidou High-Precision Navigation and Positioning Technology Innovation Center” of Hunan Shaofeng Applied Mathematics Research Institute and the School-Enterprise Cooperation Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education Base for Intelligent Railway Equipment Design in Hunan Province for providing research platform support during our affiliation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Menghani, G. Efficient Deep Learning: A Survey on Making Deep Learning Models Smaller, Faster, and Better. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.M.; Abidi, S.M.H.; Masuduzzaman, M.; Shin, S.Y. Lightweight deep learning for visual perception: A survey of models, compression strategies, and edge deployment challenges. Neurocomputing 2025, 656, 131357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvo, M.M.H.; Islam, S.K.; Cheng, J.; Morshed, B.I. Efficient acceleration of deep learning inference on resource-constrained edge devices: A review. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 42–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLO. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Xiong, G.; Zhao, M.; Li, G.; Li, R. Deep learning based online metallic surface defect detection method for wire and arc additive manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 80, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yin, J.; Huang, F.; Li, Q. Surface defect inspection of industrial products with object detection deep networks: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, A.; Yao, A. Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 25 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Bender, G.; Le, Q.V.; Ngiam, J. CondConv: Conditionally parameterized convolutions for efficient inference. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 8 December 2019; pp. 1307–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wan, F.; Duan, H.; Tong, K.W.; Deng, J.; Long, Y. FMDConv: Fast Multi-Attention Dynamic Convolution via Speed-Accuracy Trade-Off. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 317, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, B.; Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, X. OverLoCK: A ConvNet with Context-Mixing Dynamic Kernels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; p. 1–TBD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Gan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Xie, L. MobileMamba: Lightweight multi-receptive visual mamba network. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 4497–4507. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Peng, B.; Al-Huda, Z.; Malik, A.; Zhai, D. An overview of edge and object contour detection. Neurocomputing 2022, 488, 470–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Sun, Z.-J.; Sun, H.-X.; Song, X.-L. Texture feature extraction of steel strip surface defect based on gray level co-occurrence matrix. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), Guangzhou, China, 12–15 July 2015; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Peng, L.; Sun, Z. Defect detection in hot stamping process printed matter by beluga optimized support vector machine with opposition-based learning. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimozhi, I.; Janakiraman, S. An efficient approach for defect detection in pattern texture analysis using an improved support vector machine. Int. J. Bus. Intell. Data Min. 2021, 18, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Yang, M.; Jeong, J. Hybrid-DC: A Hybrid Framework Using ResNet-50 and Vision Transformer for Steel Surface Defect Classification in the Rolling Process. Electronics 2024, 13, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, Z.; He, X.; Chen, H. LA_YOLOx: Effective Model to Detect the Surface Defects of Insulative Baffles. Electronics 2023, 12, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Hsu, C.-C.; Band, S.S. A systematic review of deep learning approaches for surface defect detection in industrial applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.B.; Babiceanu, R.F. Deep CNN-based visual defect detection: Survey of current literature. Comput. Ind. 2023, 148, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Han, J.; Ding, G.; Sun, J. RepVGG: Making VGG-style ConvNets great again. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13728–13737. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.-H.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.-H.; Chan, S.-H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6194-1:2007; Rotary Shaft Lip-Type Seals Incorporating Elastomeric Sealing Elements—Part 1: Nominal Dimensions and Tolerances. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Shi, J.; Ghazzai, H.; Massoud, Y. Differentiable Image Data Augmentation and Its Applications: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 1148–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12346, pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Overall workflow of the proposed YOLOv11n_CDK algorithm.

Figure 1.

Overall workflow of the proposed YOLOv11n_CDK algorithm.

Figure 2.

Examples of oil seal images and annotated defect bounding boxes.

Figure 2.

Examples of oil seal images and annotated defect bounding boxes.

Figure 3.

Original oil seal sample data distribution and sample data distribution after data augmentation.

Figure 3.

Original oil seal sample data distribution and sample data distribution after data augmentation.

Figure 4.

General architectural flowchart of the KAN network.

Figure 4.

General architectural flowchart of the KAN network.

Figure 5.

Implementation flow of the designed NAPConv module.

Figure 5.

Implementation flow of the designed NAPConv module.

Figure 6.

The partial structure of the C3k2 network and its Dynamic variant is presented.

Figure 6.

The partial structure of the C3k2 network and its Dynamic variant is presented.

Figure 7.

Implementation flow of the designed MADConv module.

Figure 7.

Implementation flow of the designed MADConv module.

Figure 8.

Implementation flow of the proposed CondConvadaptive aggregation module.

Figure 8.

Implementation flow of the proposed CondConvadaptive aggregation module.

Figure 9.

Simplified algorithm flow of the ExpertFusionConv2d module.

Figure 9.

Simplified algorithm flow of the ExpertFusionConv2d module.

Figure 10.

Final result obtained from heatmap detection.

Figure 10.

Final result obtained from heatmap detection.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the detection effects of the main models implemented.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the detection effects of the main models implemented.

Figure 12.

The F1-score and mAP@0.5 of the YOLOv11n and YOLOv11n_CDK models vary with the confidence threshold.

Figure 12.

The F1-score and mAP@0.5 of the YOLOv11n and YOLOv11n_CDK models vary with the confidence threshold.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix of the YOLOv11n_CDK model (Confidence = 0.5, NMS IoU = 0.75).

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix of the YOLOv11n_CDK model (Confidence = 0.5, NMS IoU = 0.75).

Figure 14.

Training and validation curves for loss and detection accuracy of the YOLOv11n_CDK model.

Figure 14.

Training and validation curves for loss and detection accuracy of the YOLOv11n_CDK model.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter Configuration of YOLO, Faster R-CNN, and DETR.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter Configuration of YOLO, Faster R-CNN, and DETR.

| Hyperparameters | YOLO | Faster R-CNN | DETR |

|---|

| epochs | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| optimizer | Adam | AdamW (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, weight_decay = 0.0004) | AdamW (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, weight_decay = 0.0001) |

| lr0 | 0.01 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| lrf | 0.0005 | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Image_size | 1024 | 1024 | 1024 |

| dropout | 0.2 | None | 0.1 |

| Batch_size | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| patience | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 2.

Experimental data of the YOLOv10n to YOLOv13n and YOLOv11s frameworks.

Table 2.

Experimental data of the YOLOv10n to YOLOv13n and YOLOv11s frameworks.

| Model | F1 | mAP@0.5 | GFLOPs (B) | Parameters (M) |

|---|

| YOLOv10n | 0.78 | 0.822 | 8.2 | 2.69 |

| YOLOv11n | 0.81 | 0.838 | 6.3 | 2.58 |

| YOLOv11s | 0.83 | 0.851 | 21.4 | 9.39 |

| YOLOv11m | None | None | 182.8 | 20.9 |

| YOLOv11l | None | None | 231.2 | 26.1 |

| YOLOv11x | None | None | 519.1 | 58.8 |

| YOLOv12n | 0.81 | 0.837 | 5.8 | 2.50 |

| YOLOv13n | 0.79 | 0.830 | 6.2 | 2.45 |

| Faster R-CNN | 0.73 | 0.721 | 119.2 | 34.2 |

| DETR | 0.76 | 0.745 | 140.9 | 41.5 |

Table 3.

Performance comparison table of conditional convolution architectures with residual and bottleneck modules.

Table 3.

Performance comparison table of conditional convolution architectures with residual and bottleneck modules.

| Model | F1 | mAP@0.5 | GFLOPs (B) | Parameters (M) |

|---|

| YOLOv11n | 0.81 | 0.838 | 6.3 | 2.57 |

| MADConv | 0.81 | 0.849 | 6.1 | 2.88 |

| MADConv_B | 0.82 | 0.833 | 6.1 | 3.05 |

| MADConv_R | 0.81 | 0.847 | 6.1 | 2.88 |

| CondConv | 0.82 | 0.848 | 6.0 | 3.00 |

| CondConv_B | 0.80 | 0.829 | 6.0 | 3.30 |

| CondConv_R_B | 0.81 | 0.836 | 6.0 | 3.30 |

| ExpertFusionConv2d | 0.83 | 0.853 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

| ExpertFusionConv2d_B | 0.80 | 0.828 | 6.0 | 2.87 |

| ExpertFusionConv2d_R | 0.84 | 0.856 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

| ExpertFusionConv2d_R_B | 0.81 | 0.841 | 6.0 | 2.87 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the replacement effects of different improvement modules.

Table 4.

Comparison of the replacement effects of different improvement modules.

| Model | F1 | mAP@0.5 | GFLOPs (B) | Parameters (M) |

|---|

| YOLOv11n | 0.81 | 0.838 | 6.3 | 2.57 |

| Base_NAPConv | 0.82 | 0.837 | 6.3 | 2.58 |

| Base_C2f_Dynamic | 0.81 | 0.843 | 6.2 | 2.51 |

| Base_KANConv2d | 0.82 | 0.853 | 6.1 | 2.85 |

| Base_NAPConv_KANConv2d | 0.81 | 0.854 | 6.1 | 2.85 |

| Base_C2f_Dynamic_NAPConv | 0.82 | 0.840 | 6.2 | 2.52 |

| Base_C2f_Dynamic_KANConv2d | 0.80 | 0.848 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

| YOLOv11n_CDK | 0.84 | 0.856 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

Table 5.

Comparison of the effects of convolution at different positions and at different depths.

Table 5.

Comparison of the effects of convolution at different positions and at different depths.

| Model | F1 | mAP@0.5 | GFLOPs (B) | Parameters (M) |

|---|

| YOLOv11n | 0.81 | 0.838 | 6.3 | 2.57 |

| YOLOv11n_CDK | 0.84 | 0.856 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

| CDK_DSConv_4 | 0.81 | 0.835 | 5.6 | 2.76 |

| CDK_DSConv_6 | 0.82 | 0.853 | 5.6 | 2.66 |

| CDK_DSConv_8 | 0.81 | 0.852 | 5.8 | 2.53 |

| CDK_DSConv_4_6 | 0.80 | 0.830 | 5.2 | 2.63 |

| CDK_DSConv_6_8 | 0.81 | 0.839 | 5.4 | 2.40 |

Table 6.

The dual-path ablation experiment of the NAPConv module.

Table 6.

The dual-path ablation experiment of the NAPConv module.

| Model | F1 | mAP@0.5 | GFLOPs (B) | Parameters (M) |

|---|

| YOLOv11n | 0.81 | 0.838 | 6.3 | 2.57 |

| YOLOv11n_CDK | 0.84 | 0.856 | 6.0 | 2.79 |

| Group_1 | 0.81 | 0.835 | 5.6 | 2.74 |

| Group_2 | 0.79 | 0.823 | 5.7 | 2.77 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |