Abstract

Deep learning and image processing technology continue to evolve, with YOLO models widely used for real-time object recognition. These YOLO models offer both blazing fast processing and high precision, making them super popular in fields like self-driving cars, security cameras, and medical support. Most YOLO models are optimized for RGB images, which creates some limitations. While RGB images are super sensitive to lighting conditions, infrared (IR) images using thermal data can detect objects consistently, even in low-light settings. However, infrared images present unique challenges like low resolution, tiny object sizes, and high amounts of noise, which makes direct application tricky in regard to the current YOLO models available. This situation requires the development of object detection models designed specifically for thermal images, especially for real-time recognition. Given the GPU and memory constraints in edge device environments, designing a lightweight model that maintains a high speed is crucial. Our research focused on training a YOLOv8 model using infrared image data to recognize humans. We proposed a YOLOv8s model that had unnecessary layers removed, which was better suited to infrared images and significantly reduced the weight of the model. We also integrated an improved Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) module to boost IR image precision and applied depth-wise convolution filtering to maintain the processing speed. The proposed model achieved a 2% precision improvement, 75% parameter reduction, and 12.8% processing speed increase, compared to the original YOLOv8s model. This method can be effectively used in thermal imaging applications like night surveillance cameras, cameras used in bad weather, and smart ventilation systems, particularly in environments requiring real-time processing with limited computational resources.

1. Introduction

Recently, Object Localization and Object Classification have emerged as key research topics in computer vision. Object detection methods are broadly categorized into 1-Stage Detectors (e.g., YOLO [1], SSD [2]) and 2-Stage Detectors (e.g., R-CNN [3], Faster R-CNN [4]). While 2-Stage Detectors provide high accuracy, their slow processing speed limits real-time applications. In contrast, 1-Stage Detectors like YOLO (You Only Look Once) [1] are widely used in various fields, such as autonomous driving, security surveillance, and medical assistance, due to their fast speed and high accuracy [5]. However, most current object detection models, including YOLO, are designed and trained based on conventional RGB image data. On the other hand, infrared (IR) images with thermal detection capabilities are particularly useful in poor or insufficient lighting conditions. However, IR images typically have a lower resolution, noise issues, and smaller object sizes. Therefore, research and development in terms of specialized object detection models for infrared image data is necessary. Current research on IR object detection focuses on two main approaches. The first approach involves noise filtering methods to improve image quality [6,7,8]. However, these techniques only address noise reduction, without fully resolving resolution and object size issues. Another approach uses super-resolution techniques to enhance image resolution [6,9]. However, implementing both super-resolution and object detection simultaneously increases computational complexity, making real-time processing challenging, especially on devices with limited computing power. These limitations create the need for the development of specialized object detection models for infrared images that can process images efficiently in low-light conditions. In particular, deep learning-based object detection methods for processing infrared images have been widely used across various fields to improve detection performance [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Many approaches have been used to enhance detection performance and implement real-time applications by applying methods from the YOLO4 to YOLO8 series. However, to achieve fast processing speeds and good detection performance in resource-constrained environments like edge computing, a more suitable optimized model is needed for thermal images.

For this purpose, we propose a YOLOv8s model that has unnecessary layers removed, which is better suited to infrared images and significantly reduces the weight of the model. To help increase the processing speed, this paper applies and enhances the Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) for thermal images, while maintaining the model’s processing speed by replacing standard convolution with depth-wise convolution. This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces related work on object detection, Section 3 describes the proposed model architecture, Section 4 presents the experimental results, and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work in Object Detection

2.1. Traditional Thermal Object Detection

Thermal object detection techniques primarily use thermal cameras or infrared sensors to detect objects based on thermal differences. Traditional thermal image processing techniques include thresholding [20], edge detection [21], and region segmentation [22].

In thermal imaging, temperature distribution information is more crucial than color information. The thresholding method identifies objects by setting specific temperature values and classifying pixels above or below these values as objects. However, this method may face challenges when object temperatures are similar to the background or when objects are small. Edge detection is a technique that identifies object boundaries by locating points with rapid temperature changes in the image. Points with sudden temperature changes often correspond to object boundaries. However, this method is sensitive to image noise and can result in false detections, particularly when object boundaries are unclear or blurry.

Region segmentation is a technique that divides the image into multiple regions and identifies objects by grouping pixels with similar temperatures within each region. However, this method may encounter difficulties when object temperatures are not evenly distributed or when multiple objects overlap. Additionally, calculations can become complex when dealing with large images or multiple objects.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Object Detection

Object detection methods are broadly categorized into 2-Stage Detectors and 1-Stage Detectors. The R-CNN family of models exemplifies 2-Stage Detectors. The term “2-stage” derives from the process structure: the first stage proposes regions of interest (Region Proposal), and the second stage trains detectors based on these regions. Specifically, detection occurs through classification, to verify object presence, and regression, to predict accurate boundary boxes. This method’s evolution is demonstrated through a series of models: R-CNN, Fast R-CNN [23], Faster R-CNN, and, finally, Mask R-CNN [24].

While 2-Stage Detectors perform classification and location estimation sequentially during detector training, 1-Stage Detectors typically use dense grids at various positions and of various sizes across the entire input image, simultaneously performing classification and regression on anchors for object detection. This makes them faster than using the 2-stage approach. The 1-stage approach has evolved through the use of various algorithms, from YOLO-v1 to SSD, Retina-Net [25], and Efficient Det [26]. Notably, successive versions of the YOLO model have achieved not only faster processing, but also higher accuracy. As a result, YOLO-based object detection is widely used, even in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the aviation industry [27], autonomous vehicles, and more, where it has been proven to be highly effective. Among these, YOLOv8 [28] is currently one of the most advanced object recognition models, designed for fast and accurate object location identification and classification, making it suitable for applications requiring high speeds.

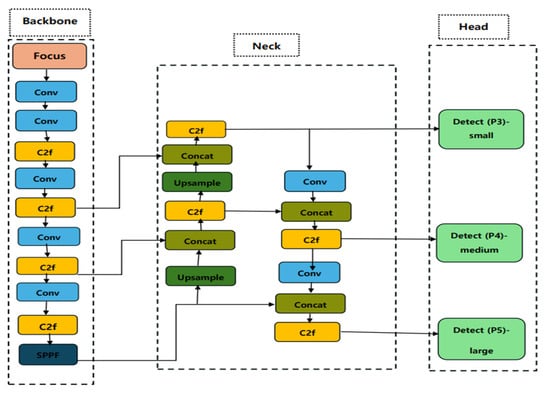

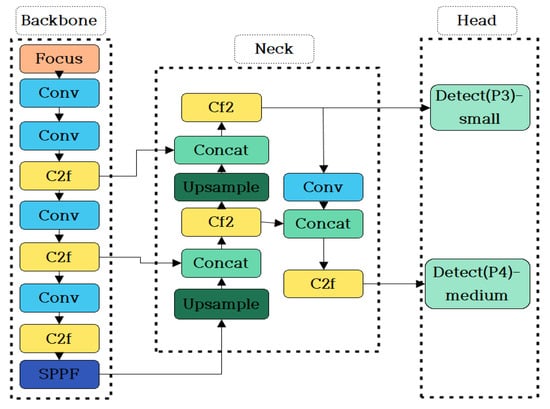

The YOLOv8 architecture (Figure 1) consists of three parts: the backbone, neck, and head. The backbone, based on an improved version of CSP Darknet, extracts feature maps from images. The neck connects the backbone and head, collecting feature maps from the backbone to assist in detecting objects of various sizes. The head locates objects based on the extracted feature maps. YOLOv8’s head consists of three parts, P3, P4, and P5_for detecting objects of different sizes. P3 (Prediction3) is best suited for small objects, P4 (Prediction4) for medium-sized objects, and P5 (Prediction5) provides high-resolution feature maps ideal for detecting large objects, effectively detecting large and distant objects.

Figure 1.

The architecture of YOLOv8.

In regard to IR images, deep learning-based thermal image recognition methods can be broadly divided into three main directions, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The first direction involves directly applying deep learning models to IR images. For example, YOLOv8-9 adapts well to various infrared spectra [10], YOLOv7 achieved a mAP of 82.4% based on the FLIR dataset [11], and YOLOv4 can detect humans, with a precision of over 95%, in smoky environments [12]. Using a CNN to detect people from infrared CCTV footage at night also falls into this category [13]. However, these methods often struggle with small objects or images with high levels of noise. These methods still require the use of many parameters and significant processing time. The second direction combines RGB and IR images to overcome these limitations and improve precision [14,15]. While this approach yields good results, it requires two separate cameras, increasing the system’s cost and complexity. The third direction focuses on improving network structures. For instance, YOLO-FIRI significantly reduces the amount of parameters (89%) and size (94%), compared to YOLOv4, while improving the mAP50 by 21% based on the KAIST dataset, but its processing speed decreases by 62% [16]. Monocular IR detection achieves a processing speed of 40 fps, but has lower precision when recognizing specific objects like bicycles (66%) [17]. Infra-YOLO, which uses MSAM and FFAFPM modules, has a complex structure, making it difficult to deploy on devices with limited resources [18]. Therefore, developing a model that can effectively handle the characteristics of thermal images, such as high amounts of noise, small objects, and low resolution, while being lightweight enough for deployment on memory-constrained devices and ensuring an adequate processing speed for real-time applications, remains a challenge that needs to be addressed.

2.3. Lightweight Techniques

While deep learning models show excellent performance in regard to image analysis, they typically require a large memory capacity and significant computational resources, which can create efficiency issues in mobile environments. Hardware limitations of robots, autonomous vehicles, and smartphones make it difficult to load and compute large models. Therefore, model optimization is essential for applying deep learning technology in real-world environments. Model optimization methods can be broadly divided into two categories.

First, Lightweight Algorithm Design involves developing lightweight model structures from scratch. For example, Res Net [29] uses shortcut connections to maintain precision, while reducing network depth, and Dense Net [30] combines feature maps from multiple layers to enhance performance. Squeeze Net [31] replaces 3 × 3 filters with 1 × 1 filters to reduce the parameter count and improve computational efficiency. Additionally, efficient filtering techniques like depth-wise convolution and pointwise convolution are used to reduce parameter counts and compress feature maps, increasing the computation speed.

Second, Algorithm Compression focuses on compressing trained models to reduce the size and improve the computation speed. This includes Pruning techniques to remove unnecessary parameters, and Quantization, which converts 32-bit floating-point values into 8-bit integers to reduce the model’s size and improve computational efficiency. Finally, Knowledge Distillation helps transfer knowledge from a large model (Teacher) to a smaller model (Student), enabling the smaller model to maintain the performance of the larger model.

2.4. Attention Mechanism

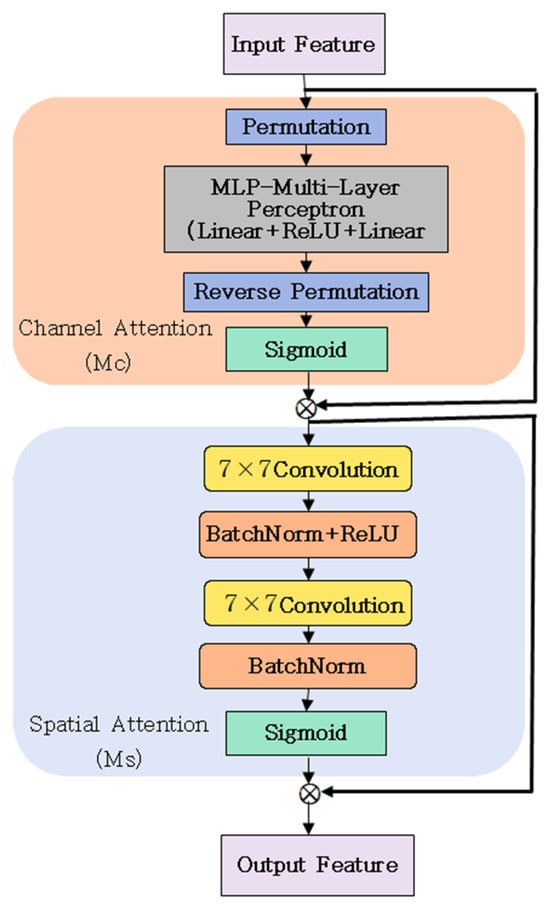

Not all information input data is equally important. The attention mechanism helps models “focus” on important parts during the learning process, similar to how humans pay attention to important details when receiving information. Particularly for input data with high levels of noise and low resolution, like thermal images, incorporating attention mechanisms into models can improve the model’s performance and accuracy by helping the model focus on important aspects of the input data. Types of attention mechanisms include Soft Attention [32], Hard Attention [33], the SE Module [34], CBAM [35], and GAM [36], with GAM showing the best performance [36]. The structure of GAM is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The architecture of GAM.

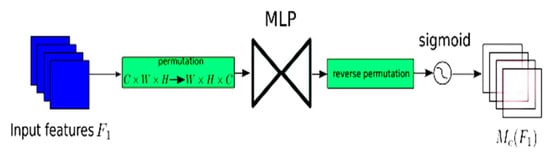

The GAM (Global Attention Mechanism) is an improved version of the CBAM module structure, aiming to minimize information loss and expand inter-dimensional interactions. The GAM consists of two main components: channel attention and spatial attention. In regard to channel attention, the GAM uses 3D permutation and a 2-layer MLP to effectively model channel and spatial information [36]. The structure of the channel attention component of GAM is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The channel attention component of the GAM.

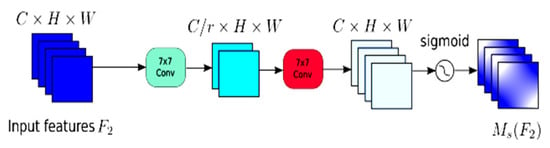

In regard to spatial attention, the GAM uses two 7 × 7 convolution layers to integrate spatial information and removes max-pooling operations to maintain more information [26]. It employs 3D permutation in the channel attention module, which enhances the ability to maintain more information from the input and improves the learning capability in terms of the inter-dimensional interaction characteristics. These improvements make the GAM a more effective attention mechanism compared to other methods, more effectively maintaining and processing information. The structure of the spatial attention component of GAM is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The spatial attention component of the GAM.

3. The Proposed System

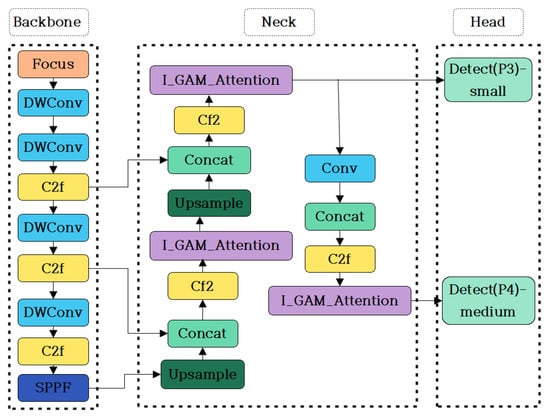

As mentioned in the previous chapter, while deep learning-based IR image recognition methods have their own advantages, designing a model that achieves both fast processing speeds and high precision for object detection using deep learning, suitable for processing IR images on resource-constrained edge devices, remains a challenge. To solve this problem, the first requirement is to create a lightweight model that aligns with the characteristics of thermal images. To achieve this, we utilized the YOLO model, particularly the latest version, YOLOv8, which offers high precision, with fast processing speeds. We propose removing the P5 layer, which is one of three layers responsible for detecting large objects, from YOLOv8’s head section. We also removed layers related to large object detection from the backbone and neck portions. This is described in Figure 5. Since P5 was originally designed for the detection of large objects and high resolutions, it is unnecessary for object detection involving infrared images.

Figure 5.

The lightweight architecture of YOLOv8.

The head section is responsible for locating objects, and since the layer for detecting large objects has been removed, the remaining layers must work harder to compensate for the deleted layer. After removing the large object detection layer, finding nearby objects also becomes more challenging, because nearby objects still occupy many pixels in infrared images. This increases the computational load and inevitably reduces the model’s precision. To improve precision and better match infrared image characteristics, we propose adding an improved GAM module structure. To maintain fast processing speeds and reduce the computational load, this paper proposes replacing the backbone’s regular convolution with depth-wise convolution. The details of adding the GAM and depth-wise convolution are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The architecture of YOLOv8, with improved GAM and depth-wise convolution applied.

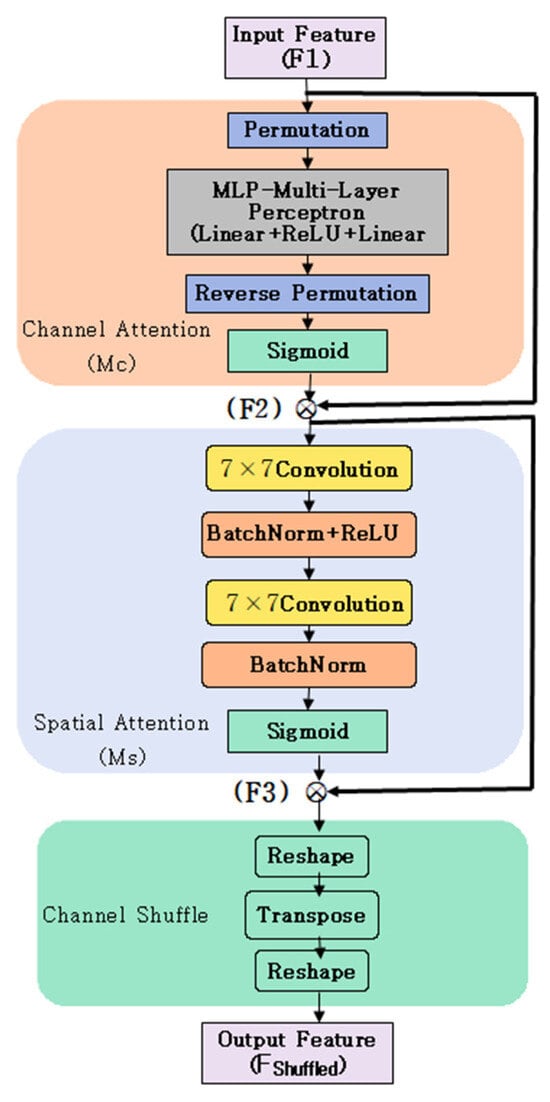

In CNN models, the attention mechanism helps the model focus on important features of the objects that need to be detected, aiding in efficient information extraction. In particular, the GAM preserves more information and improves inter-dimensional interactions compared to other attention methods. The reason for adding the GAM to the neck portion is that the neck connects the backbone and head, collecting feature maps extracted from the backbone to help detect objects of various sizes. Adding the GAM structure can improve the model’s ability to process various feature maps. However, the existing GAM structure was trained using RGB images, and compared to RGB images, thermal images have a lower resolution, contrast, and limited texture information. This makes the effective combination of information between the channel attention and spatial attention components crucial in regard to the GAM structure. Particularly, thermal images contain only single grayscale channel information, making it more important to maximize the use of this limited information. Therefore, we propose inserting channel shuffle [37] into the existing GAM structure.

Channel shuffle is a technique introduced into the Shuffle Net [26] architecture to strengthen the interaction between channel groups in convolutional neural networks. Channel shuffle is integrated into the GAM to improve the model’s learning efficiency. The process is as follows:

First, the input is the feature map F1, where F1 ∈ . Here, C represents the number of channels, H is the height, and W is the width. After applying the channel attention mechanism, the intermediate state F2 is calculated as:

where Mc is the channel attention map and Mc(F1) generates the channel attention map from F1. Moreover, ⊗ represents element-wise multiplication.

F2 = Mc(F1) ⊗ F1

Second, the spatial attention mechanism is applied to generate F3:

where Ms is the spatial attention map and Ms(F2) generates the spatial attention map from F2. F3 is the output after applying both channel and spatial attention.

F3 = Ms(F2) ⊗ F2

Third, after applying both channel and spatial attention, the channel shuffle technique is applied to strengthen the interaction between the channel groups. First, tensor F3 is reshaped into multiple channel groups. Then, each channel group is transposed, allowing information to mix between the groups. Finally, the tensor is reshaped back to its original size, as follows:

The details of the GAM structure revision are shown in Figure 7 as follows:

Figure 7.

The improved GAM architecture.

This process allows information from different channel groups to mix, enabling the network to learn more diverse and rich features, while maintaining computational efficiency and improving its generalization ability. Particularly in thermal image processing, this integration can improve the model’s overall precision and performance by detecting better patterns and features.

Meanwhile, depth-wise convolution differs from regular convolution. Instead of applying convolution to the entire feature map at once, depth-wise convolution separates the feature map according to the channel and applies small convolution filters to each channel individually. This method significantly reduces the number of parameters required and the computational load compared to regular convolution. The reason for replacing regular convolution with depth-wise convolution in the backbone is to improve the efficiency and processing speed in regard to the backbone, which accounts for the largest portion of computational load and parameters in the model. Through this replacement, we can improve the overall efficiency of the model and create a structure more suitable for real-time processing.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experiment Implementation Details

In this paper, the proposed lightweight YOLOv8-based attention model for real-time thermal image object detection on edge devices was trained on a Linux-based Ubuntu 18.04 LTS server, with an Intel Xeon Gold 640R CPU @ 2.40 GHz and a GeForce RTX 3090 24 GB. After training, the system was tested using a thermal camera, a QuantemRed VR, mounted on an edge device, an NVIDIA Jetson Orin AGX (Figure 8 and Table 1). The experimental data were collected directly using the QuantemRed VR thermal camera system (Figure 9 and Table 2). The dataset consists of a single class, namely a “Person”, focused on detecting humans.

Figure 8.

QuantemRed VR.

Table 1.

NVIDIA Jetson Orin AGX developer kit specifications.

Figure 9.

NVIDIA Jetson Orin AGX developer kit. (Manufacturer: NVIDIA; City: Santa Clara; Country: United States).

Table 2.

QuantemRed VR specifications.

The dataset comprises 768 thermal images, with a resolution of 640 × 480, divided into 590 images for training, 118 for validation, and 60 for testing. These images were captured in various lighting and environmental conditions, specifically targeting human detection. Figure 10 shows the data collection environment. The images were collected from laboratory interiors, hallways, classrooms, and school areas, with the camera height ranging from 1 m to 30 m. Figure 11 shows examples from the dataset.

Figure 10.

Dataset collection environment.

Figure 11.

Dataset examples.

In this paper, the proposed system was trained in regard to the following learning hyperparameters: learning rate, decay, channels, epochs, batch size, and optimizer. The specific hyperparameter settings for the experiment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter settings.

4.2. Evaluation Indicators and Results

We evaluated the performance of the models based on the following evaluation metrics: number of parameters, computational load (GFLOPs, Giga Floating-Point Operations Per Second), FPS (Frames Per Second), precision, and (Mean Average Precision) [38,39].

The number of parameters used in the deep learning model affects its complexity and deployability on resource-constrained devices.

The GFLOPs is calculated based on the number of floating-point operations required for matrix multiplications, convolutions, and other computations. It reflects the computational workload, helping evaluate energy efficiency and suitability for real-time applications.

The FPS refers to the number of frames processed per second. In deep learning and computer vision, FPS is used to measure the processing speed of models, such as object detection systems, indicating how many frames a model can analyze per second.

The mAP (Mean Average Precision) is a widely used evaluation metric for object detection tasks, calculated as:

where represents the average precision (the area under the precision–recall curve) for the i-th category and n is the number of categories. In this paper, we use mAP@0.5 to evaluate our model, which represents the average of the APs across all the categories when the Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold is set to 0.5 [38].

Precision represents the reliability of positive predictions, which is particularly important in applications demanding high precision [39,40]. It is calculated according to Equation (5).

where TPs (True Positives) are correctly predicted positive instances and FPs (False Positives) are incorrectly predicted positive instances. In deep learning, precision is a metric used to evaluate the performance of a classification model; especially in cases of imbalanced datasets, it measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances among all the instances predicted as positive.

The following is a performance evaluation of YOLOv8s, the lightweight YOLOv8s, the lightweight YOLOv8s with the conventional GAM structure, and our proposed model, based on the test dataset. As shown in Table 4, after removing the large object detection layer from YOLOv8s to suit thermal images, the model became significantly lighter. The number of parameters decreased from 10 million to 2.66 million, improving the processing speed from 49.5 fps to 52.35 fps, although the computational load increased and the model precision decreased. When considering mAP@0.5, the stripped-down model maintained its performance at 95.9%, slightly lower than the 97% achieved by the original YOLOv8s model. After adding the conventional GAM structure to the lightweight model, the precision significantly improved from 88.2% to 93.3%, while maintaining the mAP@0.5 at 96%. After adding channel shuffle into the existing GAM structure, the precision reached 95.3%, with a processing speed of 54.05 fps and an mAP@0.5 of 96.1%. However, the computational load was highest at 41.2 GFLOPs. To balance the precision, processing speed, and computational load, we proposed adding depth-wise convolution into the backbone, which reduced the computational load from 41.2 GFLOPs to 38.4 GFLOPs. Our final model achieved impressive results, with 96% precision (a 2% improvement over the original YOLOv8s model), an mAP@0.5 of 96.9%, an increase in the FPS from 49.5 to 55.86, and a reduction in the parameter count of approximately 75%. Therefore, our final model has a very small number of parameters, while achieving high precision and a high mAP@50, enabling it to detect objects accurately and quickly.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of the existing models and the proposed model.

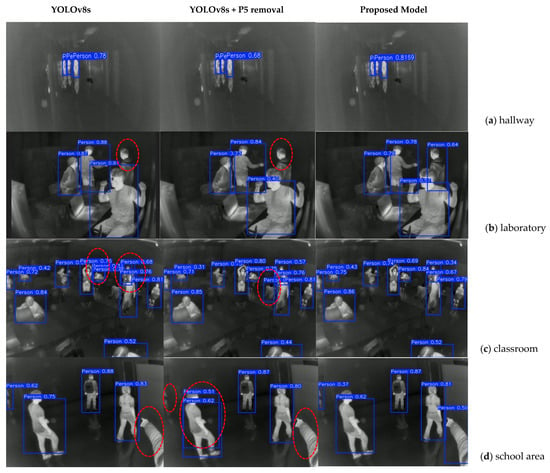

Figure 12 presents a comparison of the confidence scores [41] between the original YOLOv8s model, the lightweight model, and our proposed model using images taken in (a) a hallway, (b) a laboratory, (c) a classroom, and (d) a school area. In Figure 12a, in conditions with small and distant objects in hallways, our proposed model demonstrates a higher confidence score compared to the original YOLOv8s model. Specifically, while the YOLOv8s model detects three people, with a 0.78 confidence score, our proposed model also detects three people, but with a higher confidence score of 0.8169. Unsurprisingly, the YOLOv8s + P5 removal model has the lowest confidence score, at only 0.68. In Figure 12b, concerning the image taken in a laboratory, our proposed model achieves the best results, by accurately identifying all the individuals in the image. Specifically, our proposed model correctly identifies four people in the image, while the other two models only detect three out of the four individuals. In Figure 12c, concerning the image taken in a classroom with 10 people, the original YOLOv8s and lightweight YOLOv8s models show overlapping detections and misidentifications (highlighted with red circles), whereas our proposed model accurately detects all 10 individuals. In Figure 12d, concerning the image taken in a school area, our proposed model more precisely identifies the number and positions of the individuals compared to the other two models. Specifically, the YOLOv8s model only detects four out of five people (the red circle highlights the missed detection), while the YOLOv8s + P5 removal model shows overlapping detections and misses two people (we have marked the incorrect and missed detections with red circles).

Figure 12.

Model comparison result I. Comparison between the performance of the original YOLOv8s model, YOLOv8s + P5 removal, and proposed model using images taken in the following areas: (a) hallway, (b) laboratory, (c) classroom, and (d) school area.

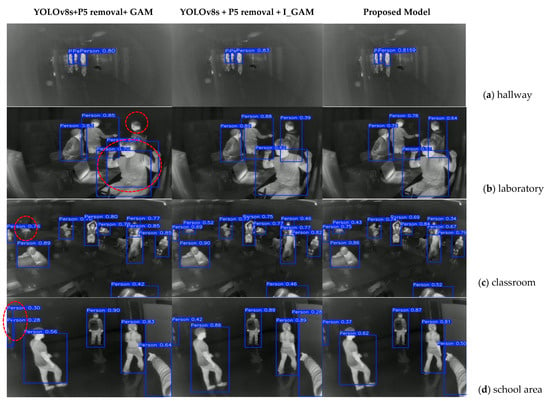

Figure 13 compares the results of the YOLOv8s + P5 removal + GAM model, the YOLOv8s + P5 removal + I_GAM model, and our proposed model. Applying I-GAM to the YOLOv8s model achieves higher recognition confidence scores compared to the model using the conventional GAM. In Figure 13a, the models using I_GAM and I_GAM + DW show confidence scores of 0.83 and 0.8169, respectively, which are higher than that achieved by the model using only the GAM (0.8). In Figure 13b, the YOLOv8s + P5 removal + GAM model shows overlapping detections and only identifies three out of four individuals. The YOLOv8s + P5 removal + I_GAM model and our proposed model demonstrate similar results in terms of detecting the number of individuals. In Figure 13c, the YOLOv8s + P5 removal + GAM model only detects nine out of ten individuals (the red circle highlights the missed detection), while the other two models correctly identify all ten individuals. In Figure 13d, the YOLOv8s + P5 removal + GAM model also shows overlapping detections (highlighted with red circles), whereas the other two models accurately and fully detect all the individuals in the image.

Figure 13.

Model comparison result II. Comparison between the performance of the (YOLOv8s + P5 removal + GAM) model, the (YOLOv8s + P5 removal+ I_GAM) model, and the proposed model using images taken in the following areas: (a) hallway, (b) laboratory, (c) classroom, and (d) school area.

From the results shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13, we evaluate that both YOLOv8s + P5 removal + I_GAM and YOLOv8s + P5 removal + I_GAM + DW models have similar confidence scores, with no overlapping detections or missed objects. Another notable point is that the first three models, 1. Yolov8s, 2. Yolov8s + P5 removal, and 3. Yolov8s + P5 removal + GAM, tend to miss objects or excessively detect incorrect objects. Over-detection typically appears in two forms: multiple bounding boxes overlapping a single object and false positives, marking areas without objects as if they contained objects. This is clearly demonstrated in Figure 12 and Figure 13. In contrast, our proposed model has very balanced precision (96%) and mAP (96.9%) values, showing that this model detects objects more accurately and minimizes the over-detection problem. Furthermore, when considering the processing speed from the results in Table 4, we can see that our proposed model not only achieves high precision and a good mAP@50 with very few parameters, but also maintains good confidence scores in regard to the images and a fast processing speed, enabling accurate and efficient object detection.

5. Conclusions

Object detection using deep learning is currently a hot area of research and is used in widespread practical applications. While most research centers on RGB images, this approach has significant limitations in low-light conditions, like nighttime or poorly lit environments. This creates a need for research into object recognition models that use thermal imaging for use in challenging lighting conditions. Real-time object detection typically needs high-end GPUs, but devices like smartphones and tablets have limited memory and GPU capabilities. This makes it crucial to develop lightweight models that are both optimized for thermal imaging and can maintain high precision without sacrificing processing speeds.

In this paper, we streamlined the existing YOLOv8s model for thermal object detection, while boosting both its precision and speed through the use of an enhanced GAM module and depth-wise convolution. Specifically, we trimmed down the YOLOv8s model by reducing the number of layers in the head from three to two. To optimize infrared detection and boost precision, we implemented an improved GAM module, while maintaining quick processing speeds through the application of depth-wise convolution. Our results show a 96% precision rate, which is a 2% improvement, along with a 12.8% increase in the FPS, while cutting down the parameter count by roughly 75%. This approach has potential applications across various fields that use thermal imaging, from nighttime surveillance cameras to self-driving cars. It is particularly valuable in situations that demand real-time processing, with limited computational resources.

However, this paper only focuses on research in laboratory environments, schools, and human class detection. To make it applicable in real-world scenarios, the research scope needs to be expanded to other environments beyond schools, such as residential areas and roads, etc., with a wider variety of object classes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-T.K. and H.T.D.; methodology, E.-T.K. and H.T.D.; software, H.T.D.; validation, H.T.D.; formal analysis, H.T.D.; investigation, H.T.D.; resources, E.-T.K.; data curation, H.T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.D.; writing—review and editing, E.-T.K.; visualization, H.T.D.; supervision, E.-T.K.; project administration, E.-T.K.; funding acquisition, E.-T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the project for Industry–University–Research Institute platform cooperation R&D funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups in 2022 (S3312736).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study was developed through a government-funded research project in collaboration with industry partners. These data will be available based on requests considering the proprietary and confidentiality requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Washington, DC, USA, 23 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.-S.; Kim, E.-T. YOLOv5-based Lightweight Methodology for Real-time Thermal Image Object Detection for Edge Devices. J. Broadcast Eng. 2024, 29, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Shao, W. Infrared image denoising based on the variance-stabilizing transform and the dual-domain filter. Digit. Signal Process. 2021, 113, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tong, Y.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Z. Infrared image enhancement algorithm based on improved wavelet threshold function and weighted guided filtering. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Engineering (EICE 2023), Guangzhou, China, 13–15 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Q. Super-resolution reconstruction of infrared images based on a convolutional neural network with skip connections. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2021, 146, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehar, R.; Vancea, F.; Marita, T.; Vancea, C.; Nedevschi, S. Object Detection in Infrared Images with Different Spectra. In Proceedings of the IEEE 15th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 7–9 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aboalia, H.; Hussein, S.; Mahmoud, A. Infrared Multi-Object Detection Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEENG), Cairo, Egypt, 21–23 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P.-F.; Liao, C.-H.; Yuan, S.-M. Using Deep Learning with Thermal Imaging for Human Detection in Heavy Smoke Scenarios. Sensors 2022, 22, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Chen, J.; Cho, Y.K.; Kang, D.Y.; Son, B.J. CNN-Based Person Detection Using Infrared Images for Night-Time Intrusion Warning Systems. Sensors 2020, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banuls, A.; Mandow, A.; Vazquez-Martın, R.; Morales, J.; Garcıa-Cerezo, A. Object Detection from Thermal Infrared and Visible Light Cameras in Search and Rescue Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 4–6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, K.; Subramanian, A. Enhancing Object Detection in Adverse Conditions using Thermal Imaging. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.13551v1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, X. YOLO-FIRI: Improved YOLOv5 for Infrared Image Object Detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 141861–141875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehar, R.; Vancea, F.; Marita, T.; Vancea, C.; Nedevschi, S. Object Detection in Monocular Infrared Images Using Classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 5–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Geng, A.; Jiang, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, D. Infra-YOLO: Efficient Neural Network Structure with Model Compression for Real-Time Infrared Small Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07455v1. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H.S.; Kim, E.T. Lightweight YOLOv5-based Attention Model for Real-Time Thermal Image Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Korea Institute of Communications and Information Sciences (KICS) Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–8 September 2023; pp. 753–754. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, V.A.; Veleva, P.K.; Sgurev, V.S. An adaptive method for image thresholding. In Proceedings of the 11th IAPR International Conference on Pattern Recognition. Vol. III. Conference C: Image, Speech and Signal Analysis, Hague, The Netherlands, 30 August–1 September 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Sun, C. Recent advances on image edge detection: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2022, 503, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutuk, Z.; Algan, G. Semantic Segmentation for Thermal Images: A Comparative Survey. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Microsoft Research. Fast R-CNN. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.08083v2. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1703.06870v3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ren, F. Light-Weight RetinaNet for Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.10011v1. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Google Research Brain Team. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.09070v7. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, K.-C.; Lau, J.; Hidayat, M. Aircraft Skin Damage Visual Testing System Using Lightweight Devices with YOLO: An Automated Real-Time Material Evaluation System. AI 2024, 5, 1793–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YOLOv8. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385v1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1608.06993v5. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360v4. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S.K.; Shaikh, M.A.; Srihari, S.N.; Gao, M. Soft-Attention Improves Skin Cancer Classification Performance. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03358v3. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, M.; Doersch, C.; Santoro, A.; Battaglia, P. Learning Visual Question Answering by Bootstrapping Hard Attention. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.00300v1. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S.K.; Shaikh, M.A.; Hu, S.N.S.J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N. Global Attention Mechanism: Retain Information to Enhance Channel-Spatial Interactions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.01083v2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, B.; Tian, H.; Jiang, D.; Sun, X. Line-YOLO: An Efficient Detection Algorithm for Power Line Angle. Sensors 2025, 25, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Tan, J.; Yan, K.; Feng, S. Lightweight UAV Landing Model Based on Visual Positioning. Sensors 2025, 25, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Developers. Classification: Accuracy, Recall, Precision, and Related Metrics|Machine Learning|Google for Developers. Available online: https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/crash-course/classification/accuracy-precision-recall?hl=zh-cn (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Datadocs. Available online: https://polakowo.io/datadocs/docs/deep-learning/object-detection#yolov3 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).