1. Introduction

With the rapid rise in the low-altitude economy and the continuous development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, UAV communication has become a significant research topic in the field of wireless communication [

1,

2]. However, due to the openness of wireless channels, UAV communication is highly susceptible to malicious jamming, especially random pulse jamming in the time domain. Moreover, the rapid time-varying characteristics of wireless channels further amplify the destructive impact of pulse jamming, posing severe challenges to the stability and reliability of UAV communication links [

3].

Traditional anti-jamming techniques, such as direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) [

4] and frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) [

5], mitigate jamming by spreading the signal spectrum to disperse the jammer’s power. However, these methods are ineffective in suppressing or avoiding highly dynamic jamming patterns such as arandom pulse jamming, and they often require large time–frequency resources to achieve sufficient processing gain, thereby significantly reducing spectral efficiency [

6,

7].

To overcome these limitations, intelligent anti-jamming technologies have emerged. By leveraging machine learning to realize dynamic policy optimization, these methods provide new insights for adaptive anti-jamming communication. For instance, ref. [

8] extended a proximal policy optimization (PPO)-based intelligent anti-jamming algorithm was proposed to formulate the anti-jamming problem as a Markov decision process and achieve fast adaptation in dynamic jamming environments [

8]; ref. [

9] applied Q-learning to fact with the environment and learn optimal anti-jamming strategies in static scenarios; ref. [

8] proposed the Slot-Cross Q-Learning (SCQL) algorithm, enabling parallel sensing and learning of multiple jamming patterns within a single timeslot, which effectively reduced learning latency and improved anti-jamming performance in rapidly changing environments. Moreover, ref. [

10] integrated Q-learning with online learning to design a dynamic power control policy that significantly reduced bit error rates and accelerated convergence; ref. [

11] introduced a Time-Domain Anti-Pulse Jamming Algorithm (TDAA), which discriminated temporal jamming patterns and adapted strategies accordingly, improving system performance under random pulse jamming. Additionally, ref. [

12] proposed the Double Q-Learning algorithm, which employed a dual Q-table structure to alleviate overestimation in conventional Q-learning, thereby stabilizing the learning process and enhancing convergence performance.

However, most of the aforementioned studies are based on the ideal channel assumption and do not fully consider the influence of the time-varying characteristics of the channel on the decision-making performance of Q-learning in the high-speed movement scenario of unmanned aerial vehicles. In high-mobility scenarios, the channel fading formed by multipath effects has a particularly significant impact on signals, which significantly reduces the effectiveness of existing anti-jamming methods when dealing with rapidly changing channel conditions [

13]. Especially when unmanned aerial vehicles collect data along prescribed routes, due to the existence of channel masking effects and multipath effects related to trajectories, the channel state changes periodically to a certain extent. Therefore, studying anti-jamming methods applicable to multipath fading in mobile communication environments is of great significance for enhancing the reliability and effectiveness of wireless communication systems.

The channel characteristics in mobile communication scenarios usually need to be characterized by using channel models. Ref. [

14] revealed that, based on the relevant two-path Rician model, multipath delay propagation would disrupt signal orthogonality, thereby leading to a significant increase in bit error rate. Reference [

15] further points out that in a time-varying channel environment, the statistical characteristics of the received signal will change rapidly over time, which leads to a decline in the reliability of jamming detection methods based on energy efficiency or spectral features, thereby increasing the modeling difficulty of intelligent anti-jamming algorithms in dynamic scenarios. For the Q-learning algorithm, the time-varying nature of the channel may bring two challenges: Firstly, the key parameters such as the amplitude and phase of the received signal fluctuate rapidly and randomly due to the multipath effect, resulting in the distortion of the state space representation based on historical data and making the convergence of the Q-table difficult; Secondly, the traditional Q-learning anti-jamming methods usually only classify the states based on “whether there is jamming”, without considering the dynamic changes in the channel. As a result, in the case where time-varying fading and random pulse jamming coexist, the communication strategy does not match the actual environment, leading to problems such as an increase in transmission failure rate and slow convergence. It can be seen from this that how to design an intelligent anti-jamming method with higher robustness on the basis of considering the influence of channel fading has become an urgent problem to be solved at present.

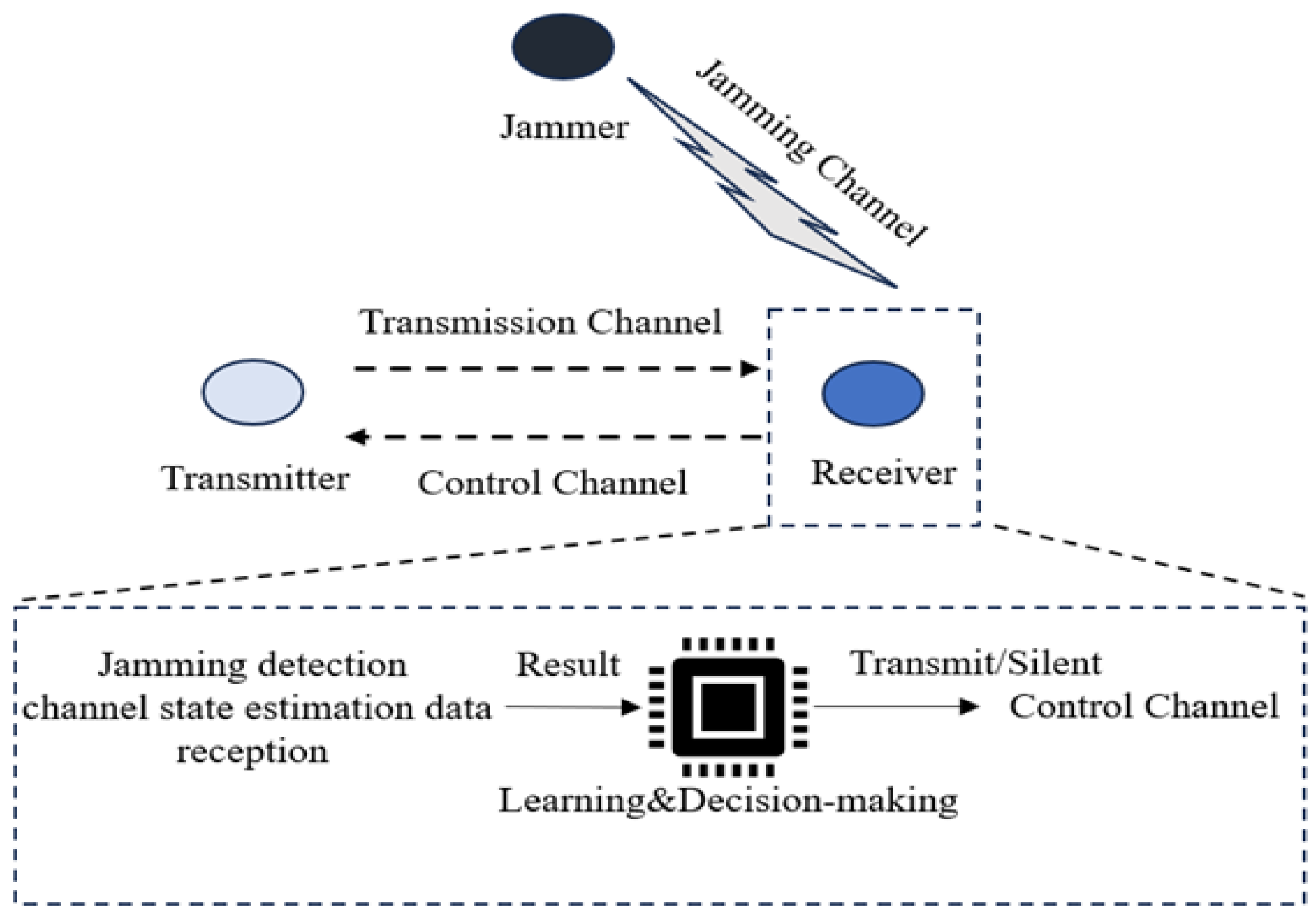

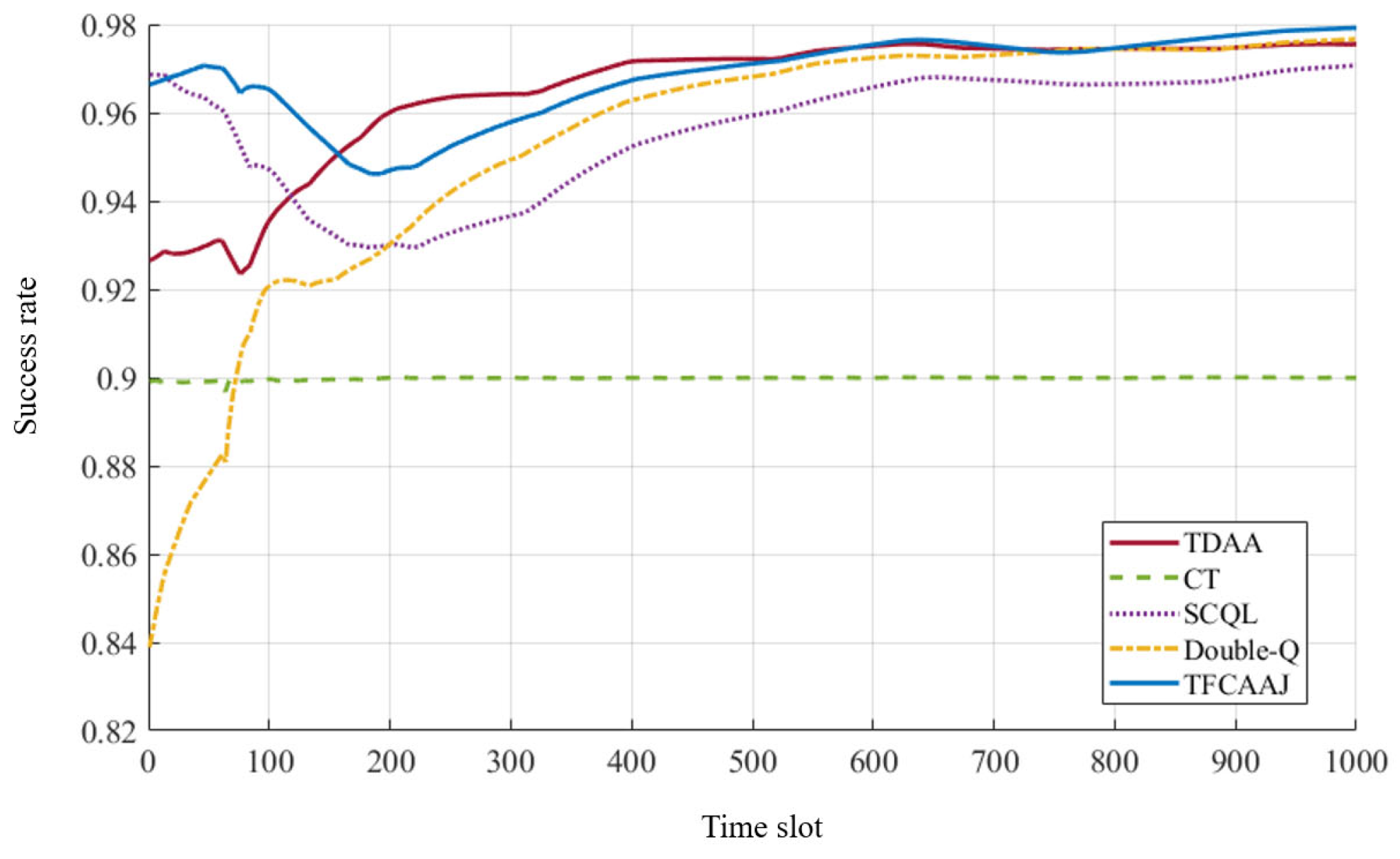

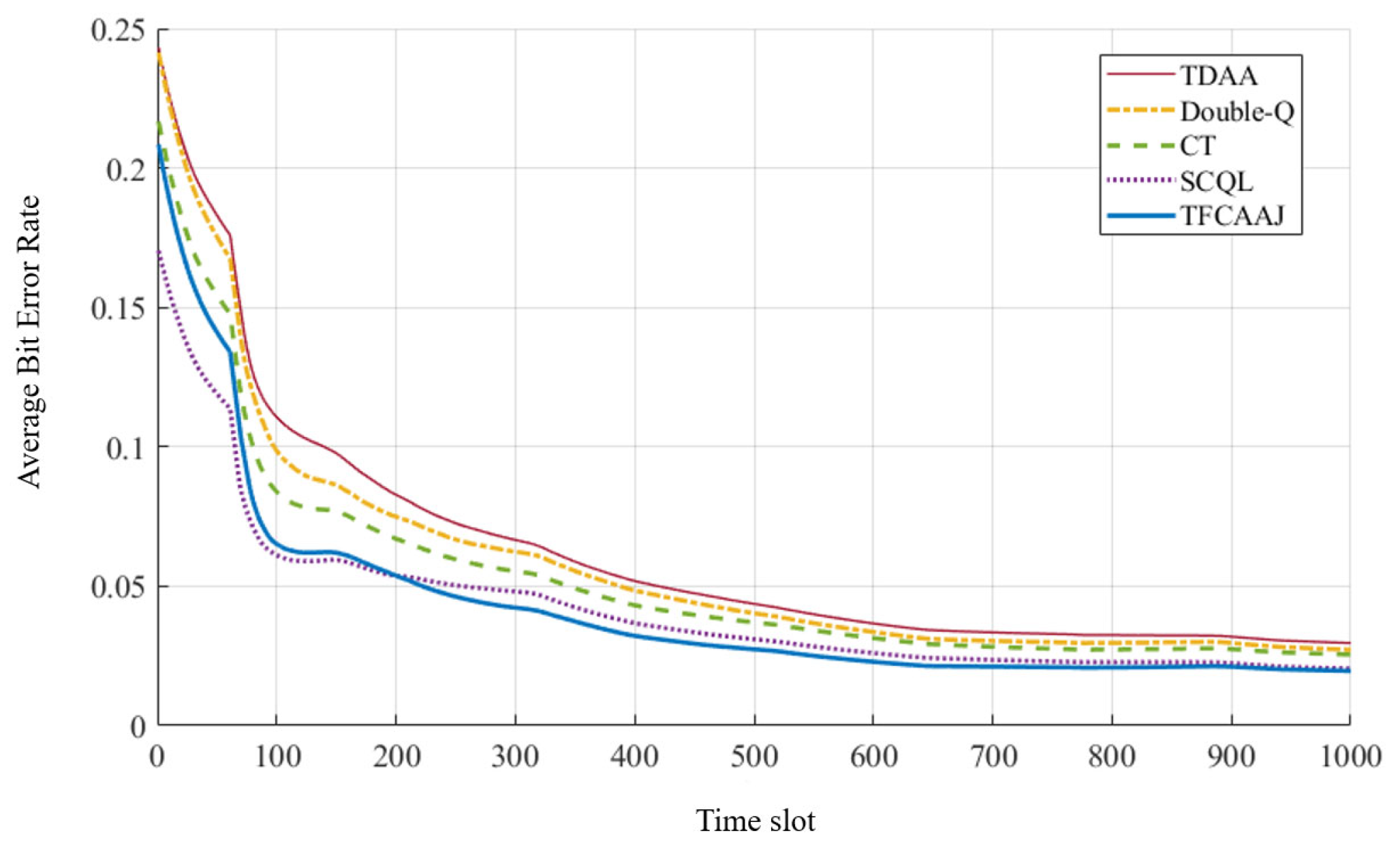

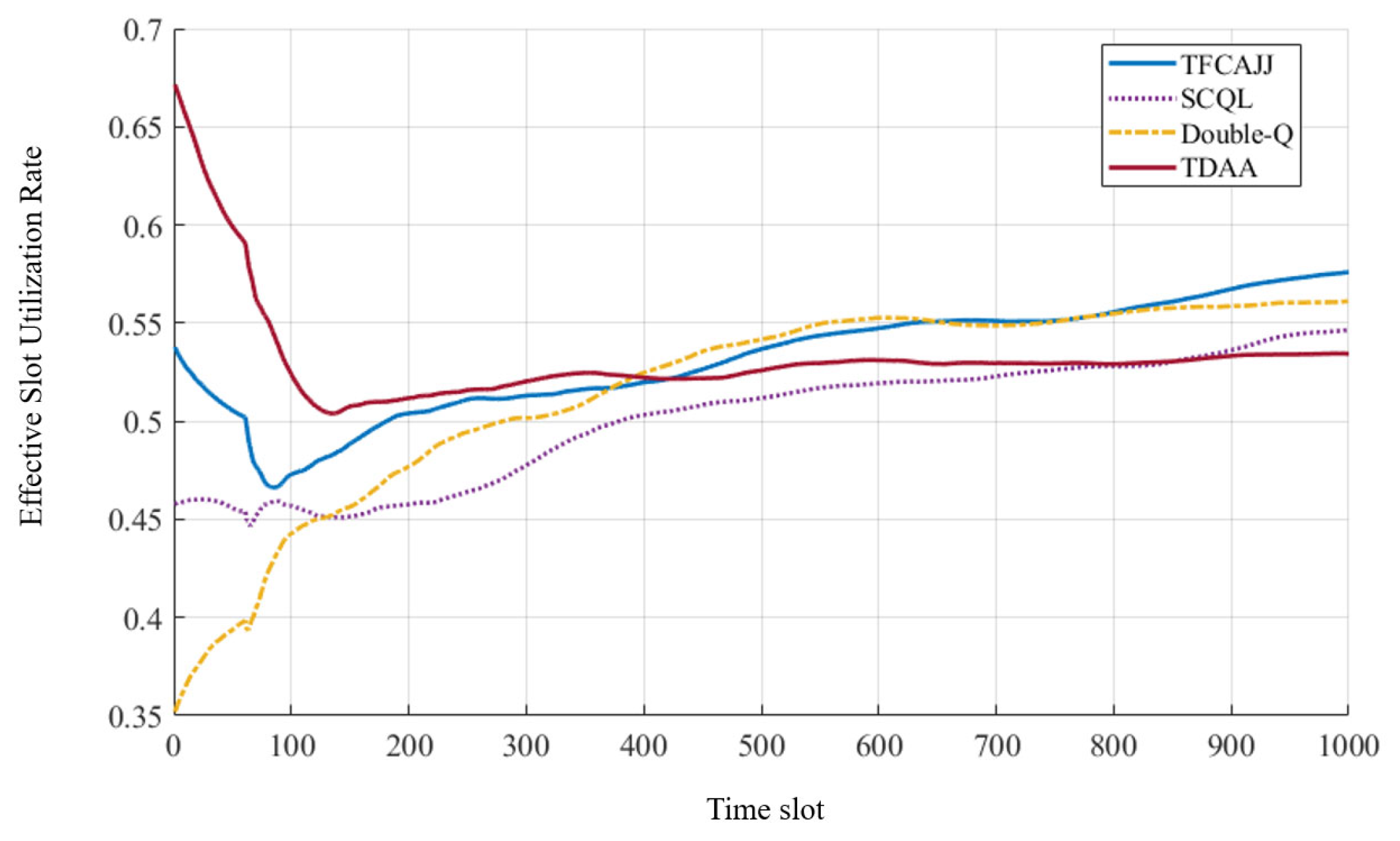

To address this issue, this paper proposes an Anti-Jamming algorithm based on Time-varying Fading Channel-Awareness (TFCAAJ). This algorithm combines the characteristics of time-domain signals with Q-learning algorithms to output a “silent/transmission” strategy, which can effectively enhance transmission reliability and improve transmission energy efficiency while ensuring the successful transmission rate of the system. The contribution of this paper includes the following two aspects:

Put forward a method based on channel perception of random pulse jamming. The Q-learning state space was optimized. By introducing the channel gain variable, the problem of transmission strategy adaptation when channel fading and random pulse jamming coexist in unmanned aerial vehicle communication was effectively solved.

Based on the optimized Q-learning decision loop, a reward function combined with channel quality and jamming characteristics was designed, which effectively suppressed ineffective communication in deep decay channels, improved the accuracy of action value estimation, accelerated the convergence speed, and enhanced the adaptability and robustness of the system in time-varying jamming environments.

3. Problem Modeling

In traditional Q-learning anti-jamming methods, the communication strategy is usually determined by simply judging whether there is jamming in each time slot. This method may be effective in a static environment or when the channel conditions are relatively ideal, but it is not reasonable enough in a complex dynamic environment, especially when there are time-varying channels. Traditional Q-learning methods usually ignore the influence of channel fading. This method ignores the fact that the time-frequency characteristics of the jamming signal change with the variation in the channel. In fact, wireless signals are affected by multipath effects through their propagation paths, causing rapid fluctuations in channel gain and signal quality over time. Therefore, the influence of jamming signals not only depends on their presence or absence but is also closely related to the fading characteristics of the channel, which makes the existing methods ineffective when dealing with dynamic channels.

For instance, when a channel encounters deep fading, even if there are jamming signals, their impact on the wireless communication link may be greatly weakened, and they may not even be correctly perceived by the wireless communication system. Traditional Q-learning methods usually overlook this point, which may lead to false alarms or missed detections in the system’s perception of jamming, thereby making incorrect anti-jamming decisions. Take pulse jamming as an example. It is assumed that there is a significant multipath delay spread in the transmission channel. When the pulse jamming signal passes through the channel, its time-domain waveform is shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that the multipath effect in the channel causes the originally steep pulse waveform to have obvious time-domain expansion and tailing effects, and the amplitude also undergoes deep random fading, which is manifested as the expansion of the jamming signal in time. This indicates that in scenarios with channel fading, if the anti-jamming decision-making method based on static assumptions is still adopted, there will be problems such as an increase in the probability of anti-jamming decision-making errors and a decrease in spectral utilization due to false alarms or missed detections of jamming.

The transmit or silent decision of the transmitter in random jamming and time-varying fading channels is modeled as a Markov decision process with a discount factor, denoted as . Here, S represents the state space, A represents the action space, P represents the probability of state transition, and R represents the reward function.

To represent both jamming and channel fading simultaneously, the state space is defined as:

In this model, each time slot is identified by an integer as its position in the current jamming period. The jamming marker indicates whether any jamming has been detected during the cycle—it is initialized to 0 at the first time slot of the cycle (i.e., ). Once a pulse is detected via the perception function in any time slot, for that slot and all subsequent slots remain set to 1 until reset at the cycle end. Simultaneously, to characterize the time-varying Rician fading channel, the envelope gain is sampled at the center of each time slot, and its amplitude follows the Rician distribution, whereas the temporal correlation between the sample is determined by the Jakes fading process and its Doppler spectrum, rather than by the marginal Rician distribution itself.” Therefore, the state triplet can fully reflect the information of time slot position, the history of jamming occurrence, and the current channel quality.

The action space includes two types: “silent” and “transmission”, which are defined as

Among them,

indicates that the transmitter takes a “silent” action. The transmitter does not transmit any signals at all during this time slot; It only performs measurement of the channel and the jamming level, and updates the corresponding state parameters.

indicates that the transmitter takes the “transmission” action. The transmitter transmits data at a fixed power

within this time slot and is simultaneously affected by possible jamming and channel fading.

In this system model, the baseband signal observed by the receiving end at each time slot is defined as follows:

Among them,

is the legitimate transmitted signal,

is additive white Gaussian noise, and

hℓ(t) denotes the time-varying complex gain of the

-th path with relative delay

, and

is the random jamming. In our simulations we consider a three-path channel (

) whose delays and average gains are given in

Table 1. We use a binary process

to mark whether there is jamming at the time slot center (1 indicates yes). Channel gain

is generated using the classic Jake model to reflect the rapid amplitude and phase changes caused by multipath propagation. At the center time

of the

t time slot, take an envelope sample of

:

Here,

represents the amplitude operator. Because the air-ground channel of unmanned aerial vehicles generally has direct paths and a large number of independent multipath components superimposed, the statistical characteristics of

follow the Rician distribution in the absence of specular component and the Rayleigh distribution in the presence of specular component. Performing arithmetic averaging over multiple consecutive time slots for

can effectively filter out short-term sharp fluctuations caused by multipath jamming, thereby reflecting the overall availability and reliability of the channel in link quality estimation and adaptive control.

The state transition from the current time slot state

to the next time slot state

is determined as follows. First, the time slot number

in the next time slot state is solely dependent on the current time slot number

, and is independent of jamming indicators or channel conditions. The specific transition is as follows:

The transfer of the jamming indicator

is influenced by the current jamming indicator

and jamming detection result

, where

indicates jamming detected in the current time slot and

indicates no jamming detected, the following holds:

During the first time slot of each jamming cycle (

), the jamming flag is initialized to 0. If jamming is first detected in any subsequent time slot (

), the jamming flag

is set to 1 starting from that slot, and remains at 1 for all subsequent time slots within that jamming cycle. This state persists until the end of the jamming cycle (

), at which point the jamming flag is reset to 0 at the start of the next cycle. Finally, the channel state

for the next time slot depends on the Rayleigh fading statistics of the channel and is independent of the current slot number and jamming identifier. It follows a Rician distribution with parameter

:

In summary, the conditional probability density function for the system to move from state

to state

after executing action

is:

Thus, the transition probability is the integral of the Rician PDF over the corresponding interval of:

The immediate reward for the transmitter executing action

a in state

s primarily encompasses the following scenarios: ① During an jamming cycle, if jamming has been detected, the data will definitely be successfully transmitted when the transmitter performs the “transmit” action in the subsequent cycle, yielding a system benefit; ② If jamming has not yet been detected, the transmission will also definitely succeed when the “transmit” action is performed, yielding a benefit; ③ If jamming is detected in the current time slot and the channel gain is

, transmission in that slot fails, resulting in system loss

; ④ When the transmitter is silent, the reward is set to 0. Based on this, the reward mechanism of the TFCAAJ algorithm is defined as follows:

Among these,

and

represent reward and penalty values dynamically calculated based on channel gain

. Specifically, the calculation formulas for

and

are as follows:

Here,

and

are the given reward and penalty values, and

is the channel gain threshold values, which are set to a fixed value.

The objective of solving Markov decision process (MDP) is to find the optimal strategy

π that can maximize the long-term cumulative reward. The state-action value function (also known as the Q value) can be expressed as:

Here,

represents the future cumulative reward obtained by starting from state

s at moment

t, first executing action

a, and then continuing to execute action according to strategy

π. This cumulative reward is composed of the weighted sum of all rewards

starting from time

t + 1, with the weights controlled by the discount factor

γ, which is typically used to represent the relative importance of future rewards. Specifically,

is the weighted expected value of all future rewards that can be obtained through strategy

π under the given current state

s and action

a conditions. When the optimal Q value corresponding to each pair of state-action combinations can be found, the optimal strategy π can be derived. This method is based on dynamic programming or other reinforcement learning algorithms and aims to maximize long-term returns by gradually optimizing the Q value. Therefore, by optimizing the Q value of each state-action pair, we can ultimately obtain a strategy that selects the optimal action in each state, thereby ensuring the maximum cumulative reward.

4. TFCAAJ Algorithm Based on Q-Learning

This paper proposes a time-domain fading channel-aware anti-jamming (TFCAAJ) algorithm based on Q-learning. In response to the above issues, this article proposes the following improvements:

State representation optimization: In traditional Q-learning methods, states are usually simply represented as a fixed state space without fully considering the dynamic changes in the channel and the complexity of jamming patterns. To solve this problem, we optimized the design of the state space, integrating the characteristics of time-varying Rician fading channels and the time-frequency characteristics of jamming. In each time slot, the status not only includes the current position of the time slot, but also the jamming-aware identification and channel gain, which can describe the changes in the environment more comprehensively. Specifically, the state triples are updated in real time within each time slot, fully reflecting the coupling relationship among the time slot position, historical jamming information, and the current channel quality. In this way, the algorithm can more accurately perceive the jamming and channel conditions in the current environment and optimize the decision-making process.

Reward function remodeling: In traditional Q-learning, the design of the reward function is relatively simple, usually only providing a fixed reward value based on the presence or absence of jamming. However, in a time-varying channel environment, relying solely on the existence of jamming is insufficient to reflect the actual system performance. To better cope with this environment, we have designed a dynamic reward function based on jamming and channel state. In this model, the reward not only takes into account whether the data is successfully transmitted, but also incorporates the jamming intensity and channel gain into the reward calculation. Specifically, when the jamming signal is strong and the channel quality is poor, transmission failure will bring a relatively high penalty. Conversely, if the jamming signal is weak or the channel quality is good, the transmission will be successful and the corresponding reward will be obtained. This improvement enables the reward function to be dynamically adjusted to adapt to the time-frequency variations in channel fading and jamming, better meeting the requirements in actual communication.

At each time slot, the transmitter selects to perform the “transmission” or “silent” action based on the current status and updates the status according to the received jamming feedback. Through the Q-learning mechanism, the transmitter constantly adjusts its strategy to maximize the transmission success rate under the influence of interfering signals and avoid unnecessary collisions and failures. Initially, the algorithm randomly initializes the Q-values for each time slot. Subsequently, in each time slot, the transmitter performs transmission based on the current state

and the selected action

, while the receiver updates the state

and instant reward

based on the jamming perception feedback. The receiver then uses the Q-value update formula to optimize the current action and selects the action

for the next time slot:

In the Q-learning update,

denotes the learning rate that controls how strongly new observations override old estimates.

The algorithm process is as follows (Algorithm 1):

| Algorithm 1 Time-varying Fading Channel-Awareness (TFCAAJ) |

| 1: Initialization: ; For any ,. |

| 2: for do. |

| 3: The transmitter performs the decision action or initial action of the previous time slot and calculates the channel condition . |

| 4: Detect whether jamming exists in the current environment during the perception sub-slot . |

| 5: The receiver calculates the immediate reward and the next state based on the jamming perception result and the channel state . |

| 6: The receiver updates the Q value according to Formula (14). |

| 7: The receiver infers the next action based on the update criterion, which is as follows: |

|

| 8: The receiver generates a new strategy and passes the new strategy to the transmitter. |

| 9: end for |