1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of emerging technologies, the demand for high-capacity and high-speed transmission continues to grow [

1,

2,

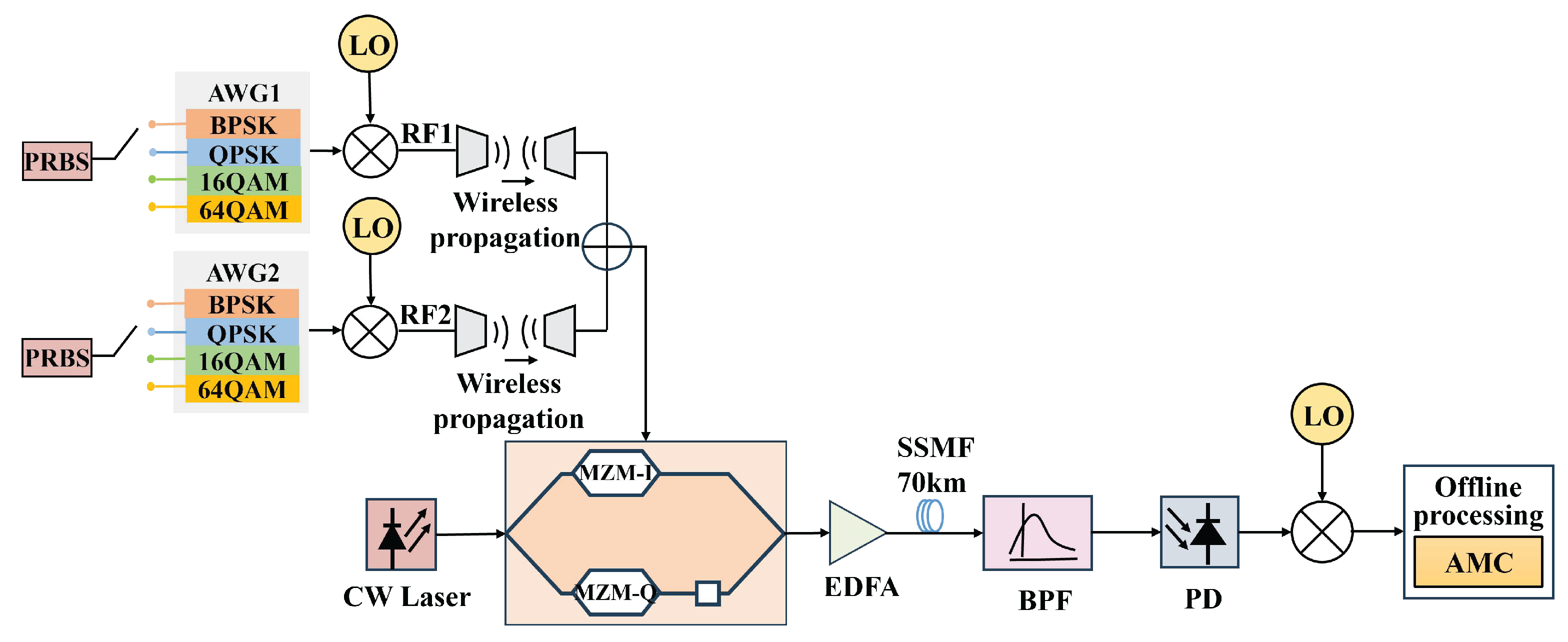

3]. However, the spectrum below 6 GHz is becoming increasingly congested, while the millimeter-wave (mmWave) band from 30 to 300 GHz, despite its vast potential, remains underutilized. Owing to its short wavelength, high propagation loss, and severe multipath effects, mmWave communication suffers from a limited transmission range in wireless channels, posing challenges to achieving large scale and reliable connectivity. Radio-over-fiber (RoF) technology provides a promising solution by integrating the flexible access of wireless communication with the high bandwidth and low attenuation of optical fiber links. This combination not only extends the transmission distance of mmWave signals and reduces system cost but also enables Gbps-level high-speed data transmission. Consequently, RoF offers a feasible pathway for constructing next generation wireless networks with high capacity and broad coverage.

On the basis of efficient transmission of the RoF system, accurate identification of signal modulation formats in complex environments has become a key challenge for further improving communication performance. Automatic modulation classification (AMC) is a promising technology with wide ranging applications, playing a critical role in both modern military communications and civilian electromagnetic monitoring. Typical applications include intercepted signal demodulation and recovery, spectrum surveillance, and related tasks [

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, AMC has been the focus of extensive researches, giving rise to a variety of methods that can generally be classified into two categories: likelihood-based (LB) decision theoretic approaches, which rely on likelihood ratio tests, and feature-based (FB) statistical pattern recognition approaches, which rely on feature extraction. Compared with LB methods, FB approaches have attracted more attention in recent years due to their advantages of lower computational complexity and more stable performance [

7]. For instance, a novel feature derived from fourth-order and sixth-order cumulants was proposed in [

8], where a neural network classifier was employed to distinguish nine modulation formats, including ASK, PSK, and MSK. Similarly, nonlinear power transformation techniques have been applied for the classification of M-ary PSK and QAM signals [

9]. More recently, deep learning-based AMC methods have gained significant traction, leveraging models such as deep neural networks (DNNs) [

10,

11], residual neural networks (ResNets) [

12,

13], convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

14,

15], and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) [

16,

17].

In RoF systems, complex optical impairments such as phase noise, chromatic dispersion, and fiber nonlinearities significantly challenge the performance of traditional AMC algorithms originally designed for wireless communication environments, highlighting the urgent need for targeted improvements and optimization. To address this issue, an autoencoder neural network was proposed for automatic feature extraction and classification in RoF systems [

18]. Meanwhile, with the widespread deployment of diverse devices such as radar, communication, navigation, and broadcasting, multiple signals from different sources are often received simultaneously, leading to increasingly severe time–frequency aliasing. In such environments, conventional AMC methods designed for single-signal scenarios are no longer sufficient for practical applications. Consequently, recent research has shifted toward AMC algorithms for mixed signals. For example, a mixed-signal recognition method based on cyclic spectral projection and deep neural network is proposed, using gray projection on the two-dimensional cyclic spectrum for feature enhancement, achieving effective recognition of mixed signals [

19]. A multi-signal modulation classification method based on sliding window detection and a frequency-domain complex CNN is proposed. The overlapping time-domain signals are transformed via FFT, segmented by energy detection, and classified accurately using the CNN [

20]. However, these methods still do not consider the influence of complex optical impairment effects such as laser phase noise, dispersion, and nonlinear effects on the performance of mixed-signal AMC. Therefore, the development of a high-efficiency mixed-signal AMC technique for RoF system is both necessary and highly anticipated.

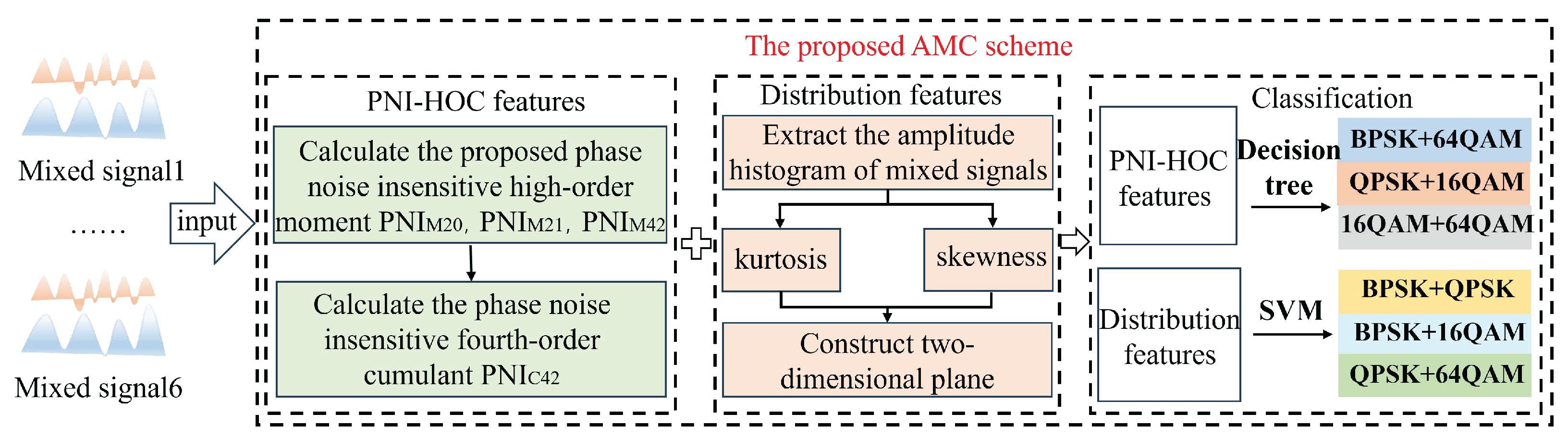

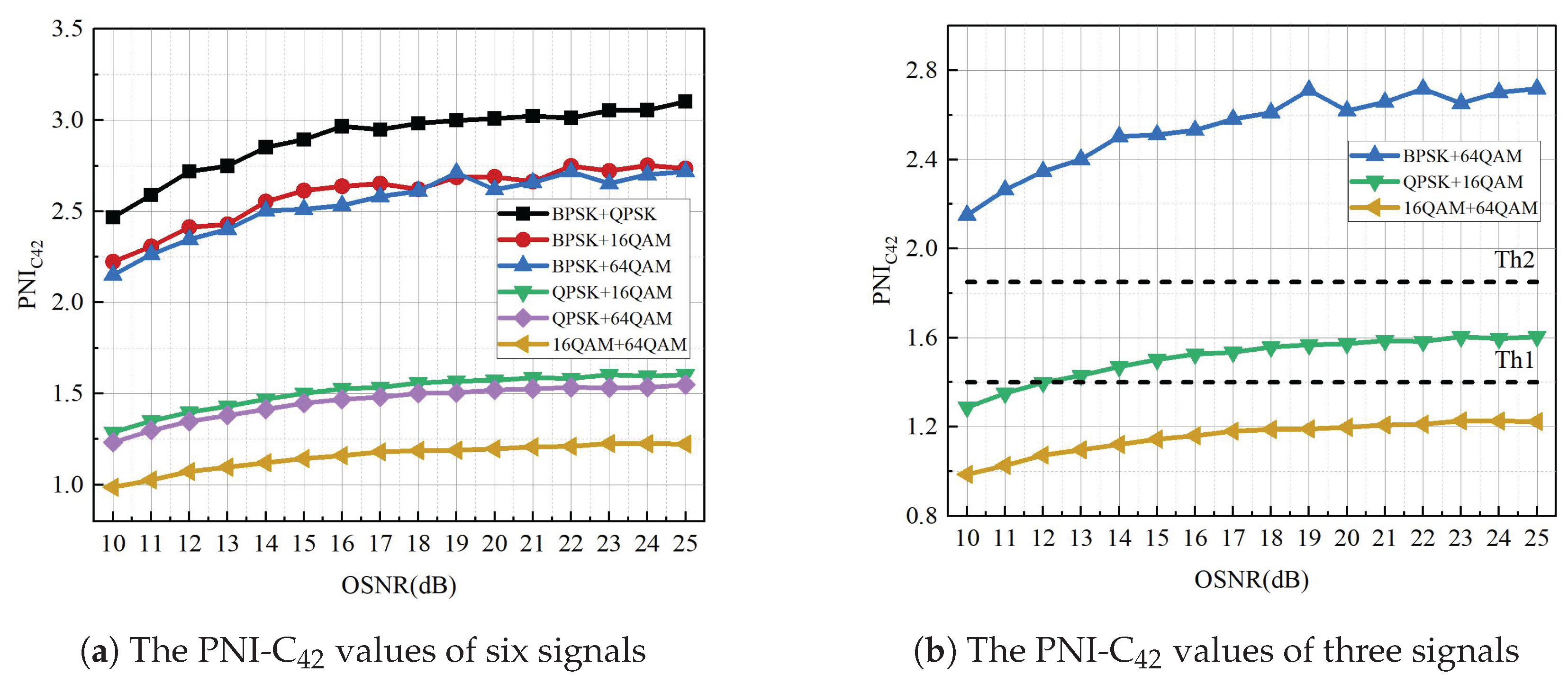

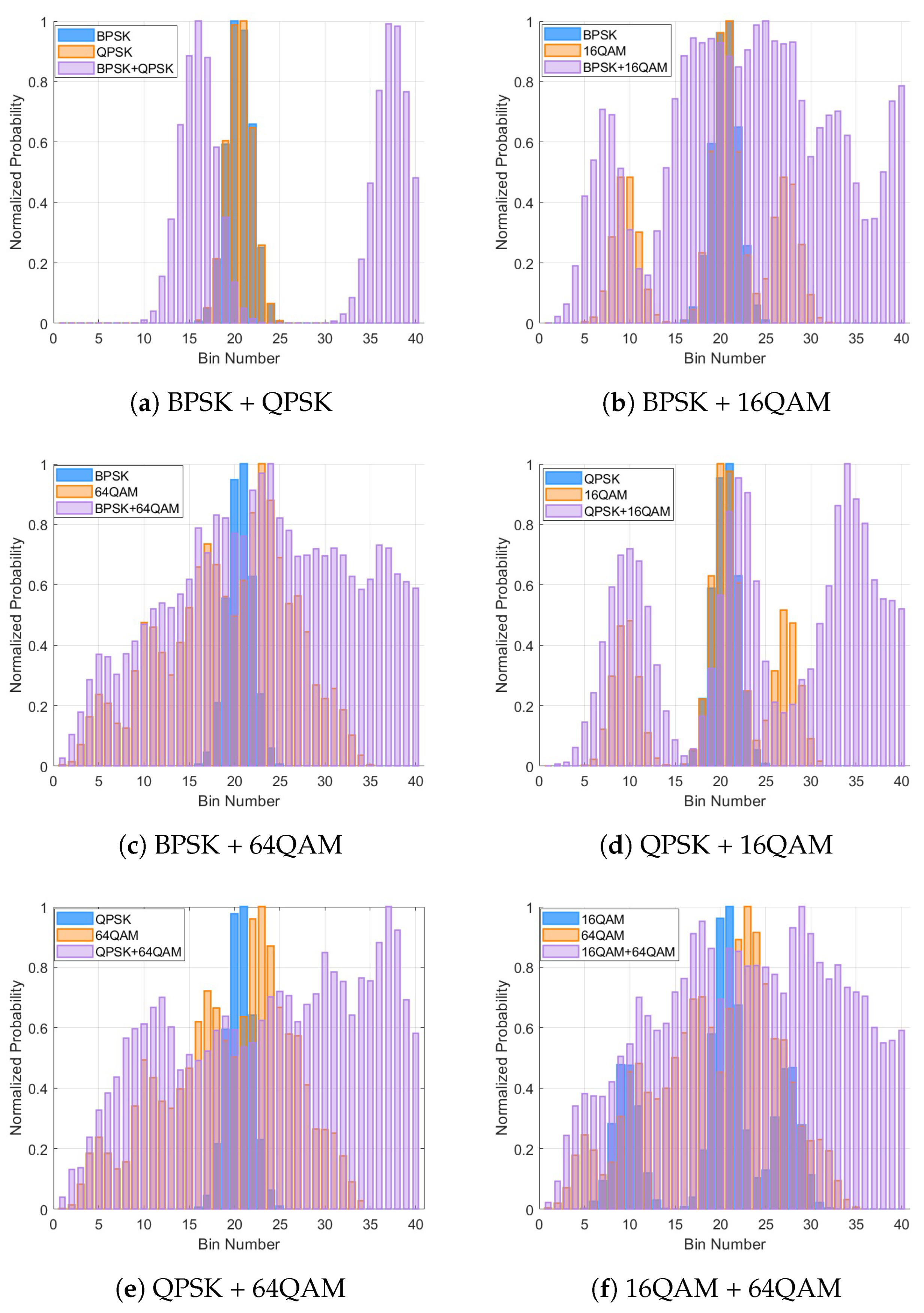

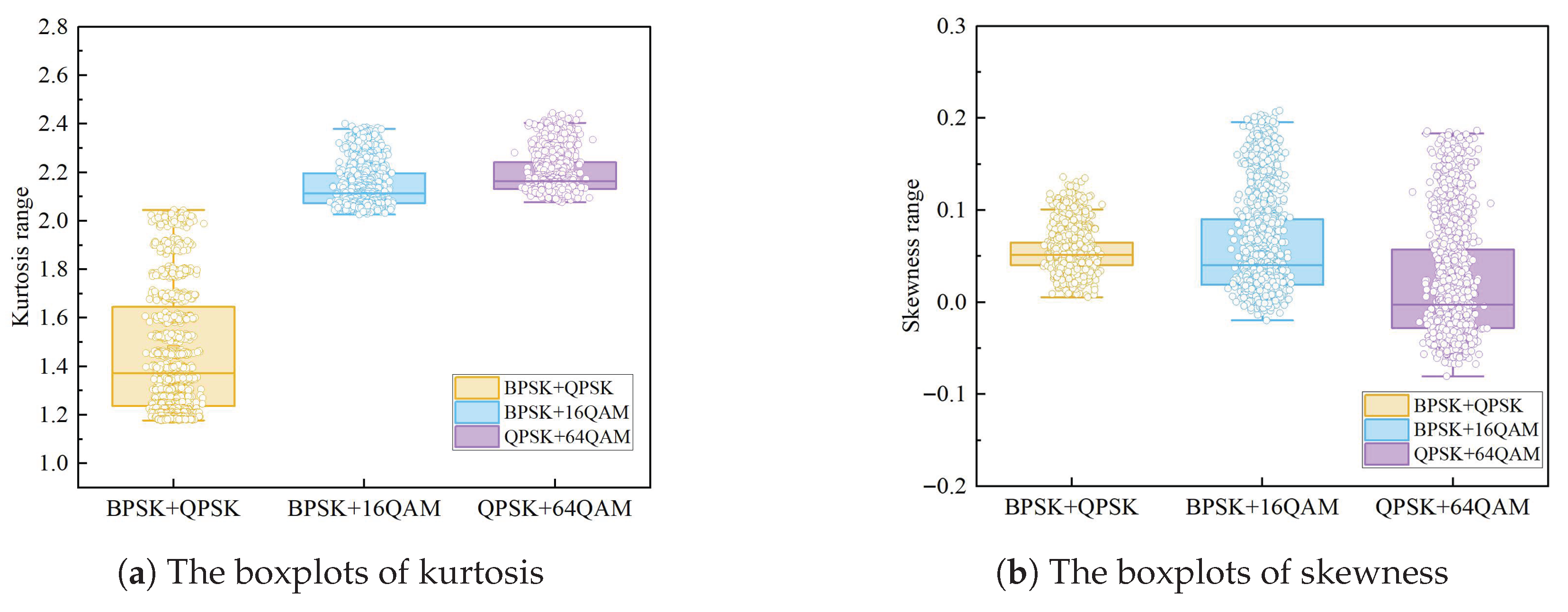

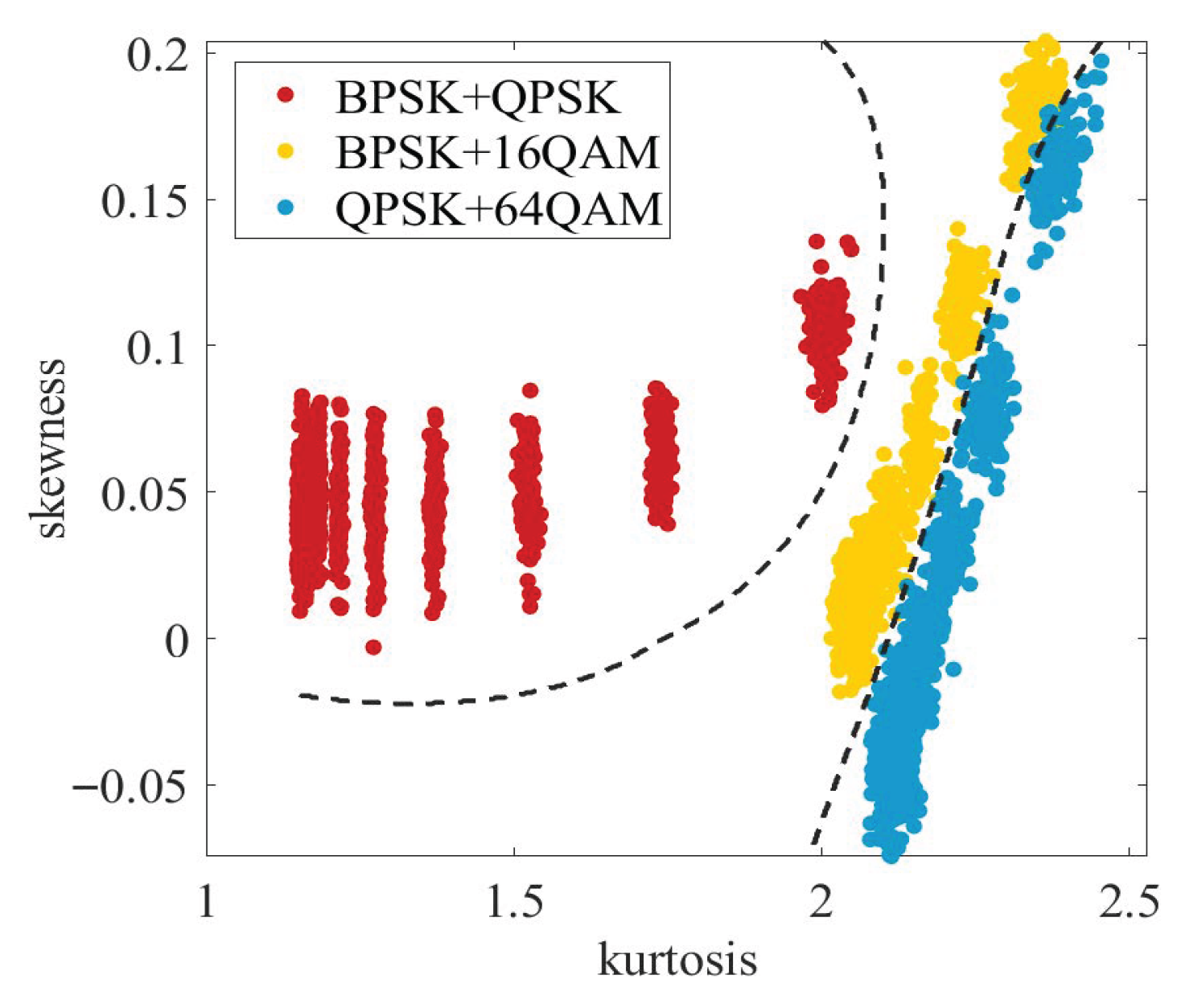

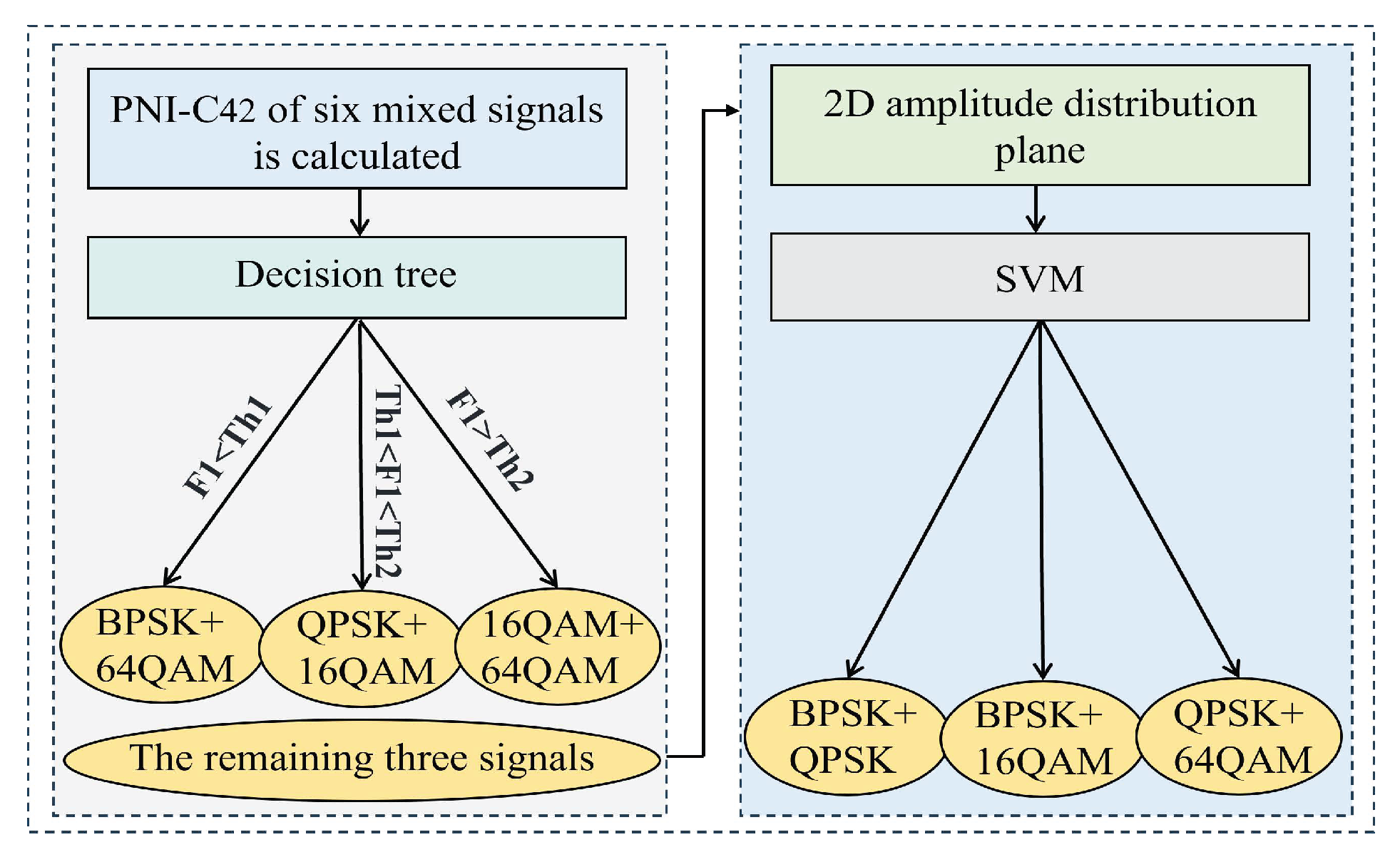

In this paper, a mixed-signal AMC method based on PNI-HOC and distribution characteristics in ROF system is proposed, which can accurately identify the mixed modulation formats. Firstly, a PNI-HOC algorithm is proposed and its value for the mixed signal is calculated. Then, the distribution characteristics kurtosis and skewness of the signal histogram are extracted to construct a two-dimensional plane. These characteristics are subsequently input into decision tree and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers for modulation classification. The proposed method effectively compensates for the influence of laser phase noise on high-order cumulants and achieves reliable identification of mixed modulation formats. To validate its effectiveness, a 10 GBaud RoF system with a 70 km fiber link is simulated, with the OSNR varied from 10 dB to 25 dB in 1 dB increments. The AMC scheme determines the six mixed signals composed of PSK signals and QAM signal, namely BPSK + QPSK, BPSK + 16QAM, BPSK + 64QAM, QPSK + 16QAM, QPSK + 64QAM, and 16QAM + 64QAM. To demonstrate the feasibility and superiority of this scheme, simulation results show that, compared with the conventional high-order cumulant method, the approach solely based on amplitude histogram distribution characteristics and the scheme based on the deep neural network (DNN) classifier using histogram characteristics, the proposed scheme achieves superior classification performance at low OSNR. In particular, when the fiber length is 70 km and the OSNR is ≥16 dB, the recognition accuracy of the six mixed signals remains consistently at 100%.

4. Simulation Results and Discussions

To validate the superiority and feasibility of the proposed scheme, simulations are conducted over a 70 km transmission link using the optimal configuration of training samples and symbols. Specifically, each modulation format sample contained 16,384 symbols, with 80% of the total samples allocated for training and the remaining 20% reserved for testing.

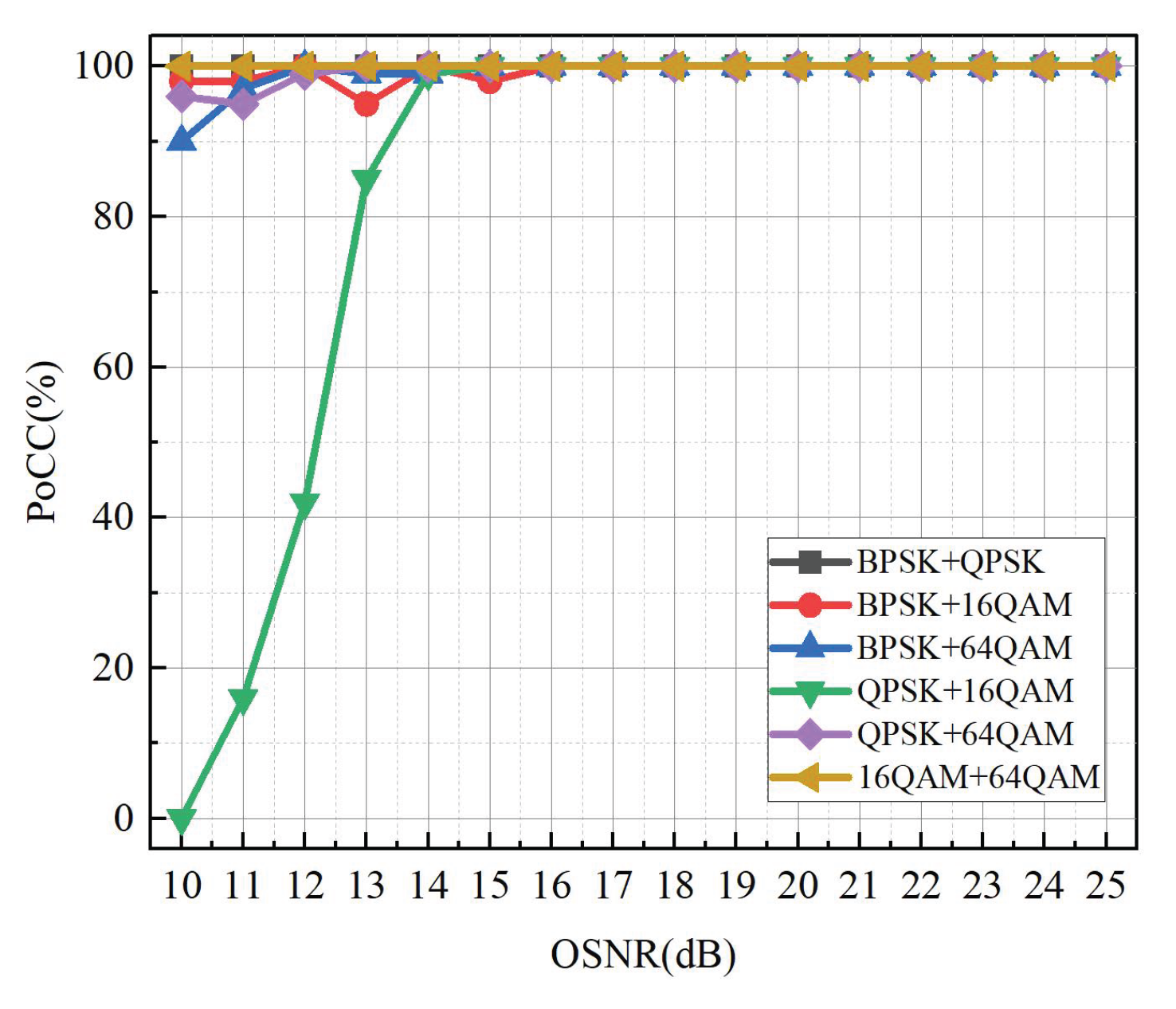

Figure 9 presents the probability of correct classification (PoCC) for the six mixed signals under OSNR conditions ranging from 10 to 25 dB. The OSNR values at which the PoCC of BPSK + QPSK, BPSK + 16QAM, BPSK + 64QAM, QPSK + 16QAM, QPSK + 64QAM, and 16QAM + 64QAM reaches 100% and remains stable are 10 dB, 16 dB, 15 dB, 15 dB, 13 dB, and 10 dB, respectively. When the OSNR is relatively low, the received signal quality deteriorates due to increased noise, which can cause partial overlap of constellation points and lead to classification errors. However, even under lower OSNR conditions (<16 dB), the proposed scheme can still maintain a relatively high PoCC, with most mixed signals achieving accuracy above 90%. These results confirm that the proposed AMC method maintains high classification accuracy and demonstrates strong robustness, even under low OSNR conditions.

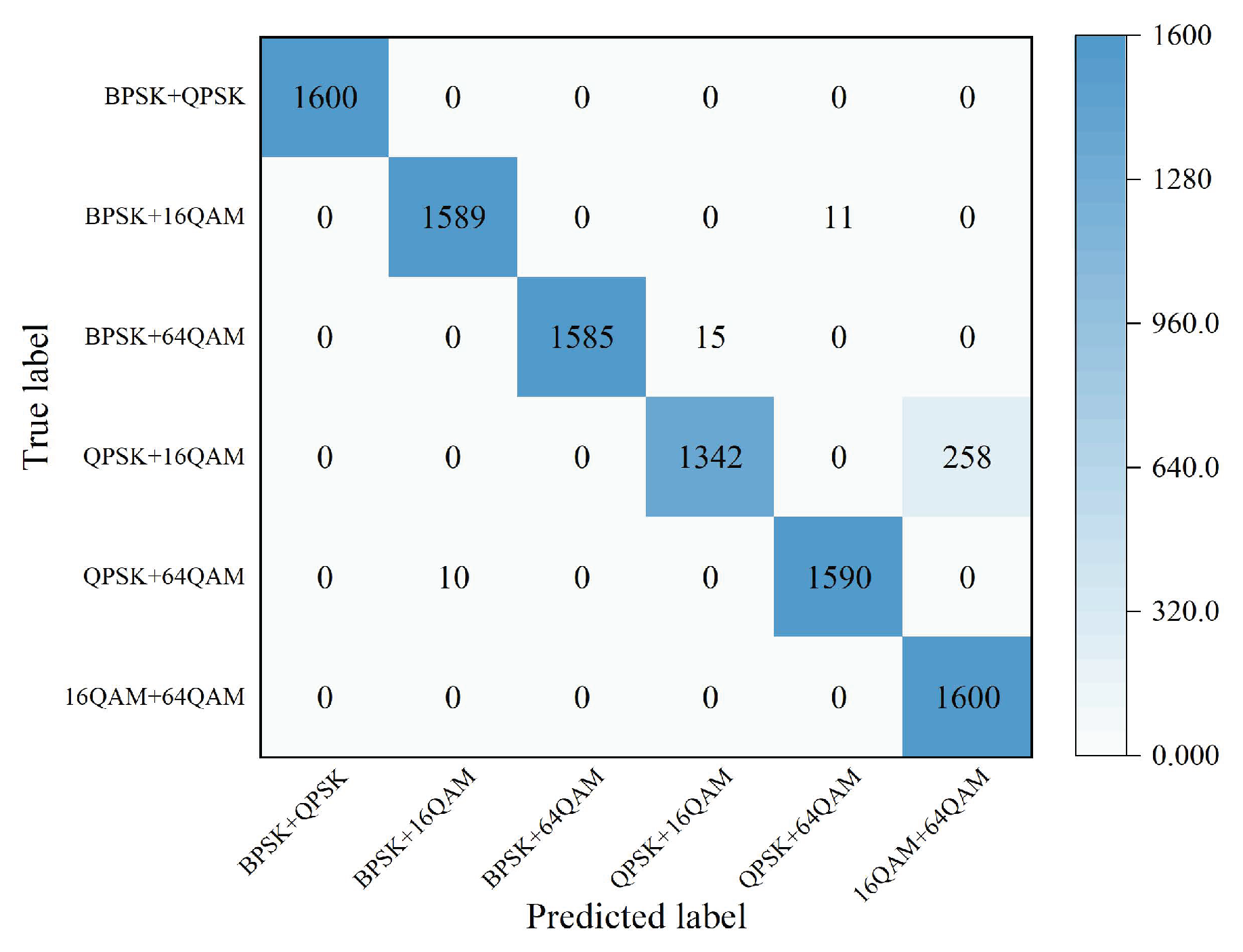

Figure 10 shows the confusion matrix for six mixed signals under the proposed scheme. In the matrix, the horizontal axis denotes the predicted class and the vertical axis denotes the true class. The diagonal entries indicate the numbers of correctly classified samples. Across the examined OSNR range, the average PoCC for BPSK + QPSK, BPSK + 16QAM, BPSK + 64QAM, QPSK + 16QAM, QPSK + 64QAM, and 16QAM + 64QAM are 100.0%, 99.3%, 99.1%, 83.9%, 99.4%, and 100.0%, respectively. Overall, the confusion matrix demonstrates that the proposed method achieves excellent performance in distinguishing the six mixed signals, validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

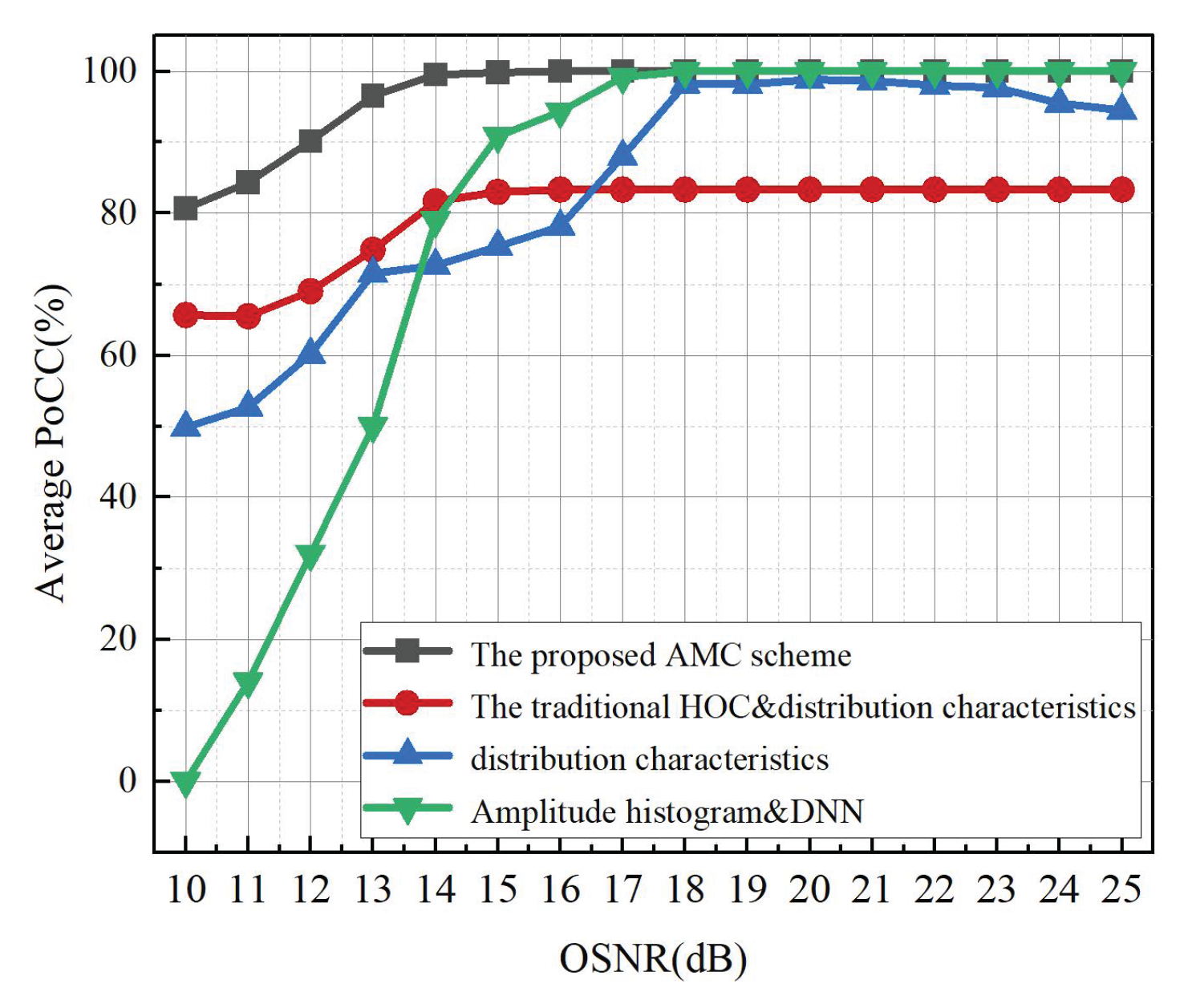

To further demonstrate the superiority of the proposed AMC scheme, its performance is compared with several alternative approaches under a 100 kHz laser linewidth. As shown in

Figure 11, the proposed scheme maintains 100% average PoCC for OSNR ≥ 16 dB. In contrast, the DNN-based histogram method reaches 94.3% at 16 dB and achieves 100% only when the OSNR is ≥18 dB. The traditional HOC combined with amplitude distribution characteristics attains 83.3% at 16 dB with no improvement at higher OSNRs, while the method based solely on amplitude distributions yields 78.1% at 16 dB and peaks at 98.8% at 20 dB. Overall, these results demonstrate that the proposed AMC scheme provides significantly higher accuracy and stronger robustness across a broad OSNR range.

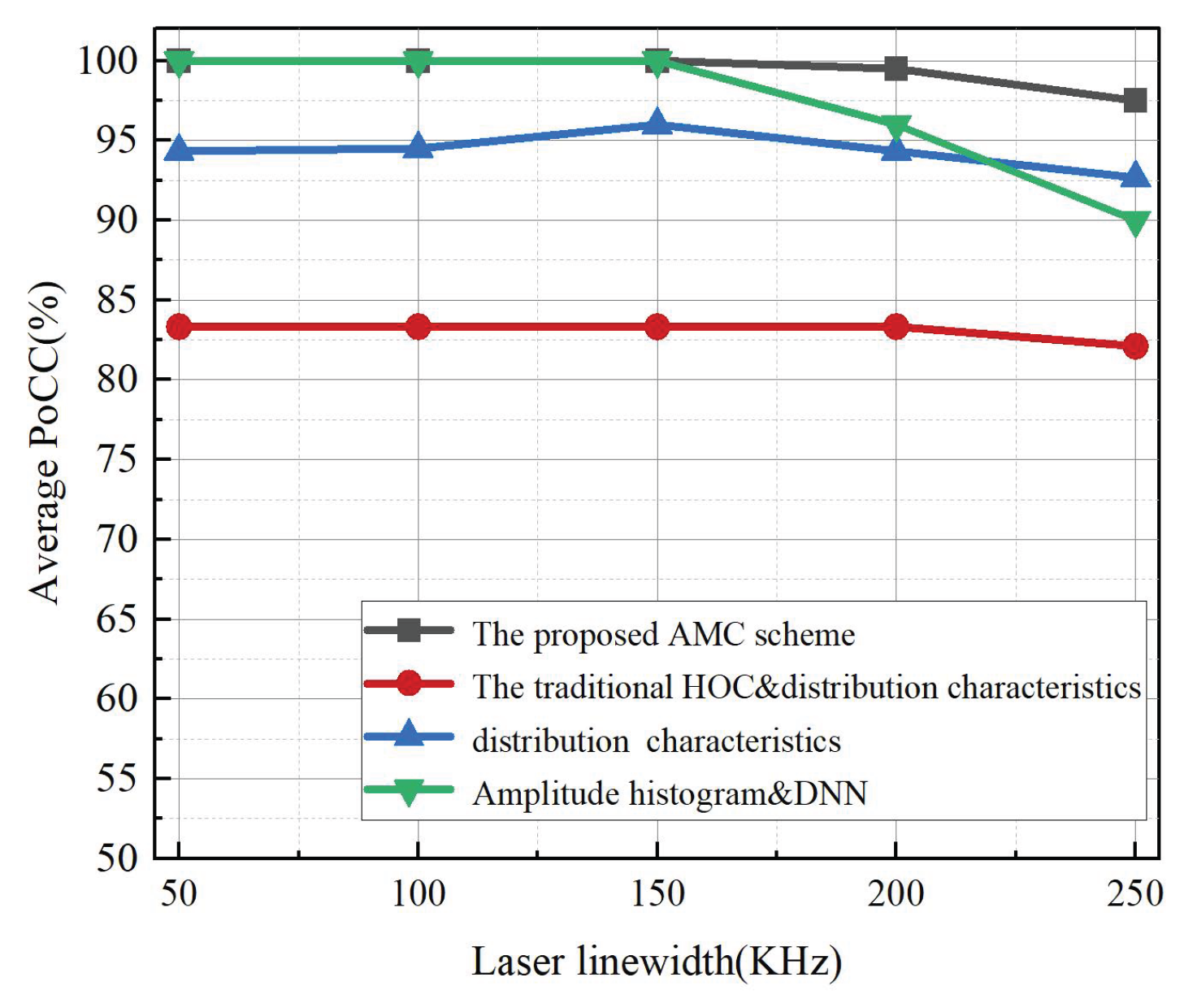

To further assess the tolerance of different AMC schemes to laser phase noise,

Figure 12 shows their performance at an OSNR of 25 dB under linewidths of 50 kHz, 100 kHz, 150 kHz, 200 kHz, and 250 kHz. When the linewidth is 50 kHz, 100 kHz, or 150 kHz, both the proposed scheme and the DNN-based scheme maintain a stable 100% average PoCC. In contrast, the traditional HOC combined with distribution characteristics remains at 83.3%, while the scheme using only distribution characteristics peaks at 96%. As the linewidth increases to 200 kHz, the proposed method shows only a slight decrease to 99.5%, whereas the other three schemes drop to 83.3%, 94.3%, and 96%. At 250 kHz, the proposed scheme still achieves 97.5%, while the alternatives fall to 82.1%, 92.6%, and 90%. These results indicate that although laser phase noise degrades AMC performance, the proposed method maintains strong robustness and high accuracy across practical linewidth conditions.

To further assess the robustness of the proposed AMC scheme under multipath fading, we extend the analysis to Rician fading channels.

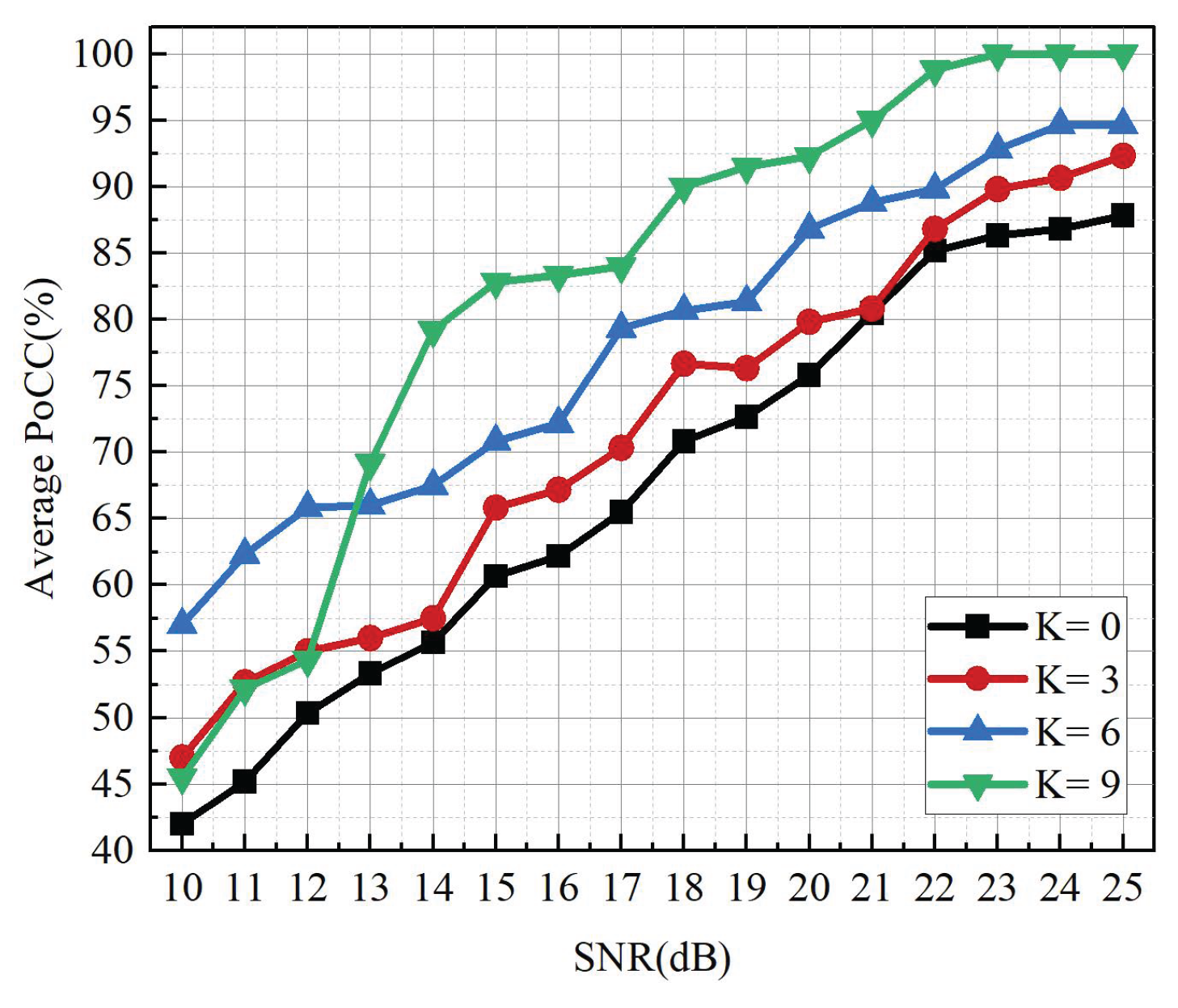

Figure 13 shows the average PoCC of the six mixed signals under a four-path Rician channel with different K factors, K = 0, 3, 6, and 9. The K factor represents the power ratio between the LOS component and scattered multipath components, where a larger K indicates weaker fading. The results show that the proposed AMC scheme maintains 100% average PoCC for SNR ≥ 23 dB when K = 9. For K = 6 and K = 3, the maximum average PoCC reaches 94.7% and 92.3%, respectively. Under the most severe fading, K = 0, the average PoCC is about 85% at high SNR, with a peak of 87.8%. These results indicate that the proposed AMC algorithm maintains stronger robustness even in the presence of pronounced multipath fading.

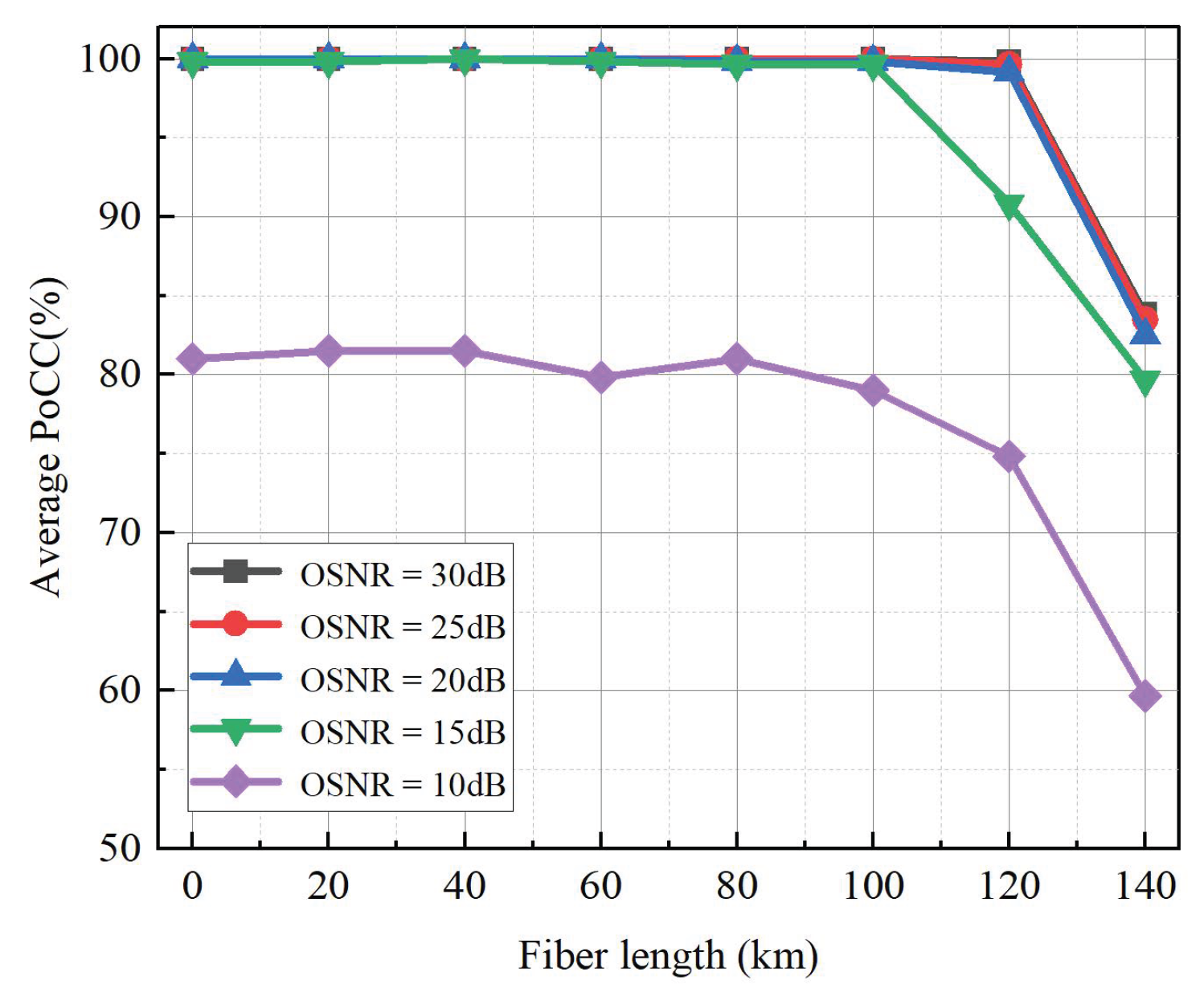

Figure 14 illustrates the relationship between the performance of the proposed scheme and fiber lengths under OSNR values of 10 dB, 15 dB, 20 dB, 25 dB, and 30 dB. The fiber length ranges from 0 to 140 km in steps of 20 km, and each OSNR condition is simulated using 100 sets of 16,384 symbols. The results show that at OSNR values of 25 dB and 30 dB, the average PoCC reaches 100% in the fiber length range of 0 to 100 km, and when the fiber length is 140 km, the average PoCC is 83.8% and 83.5%. When the OSNR is 15dB, the average PoCC reaches 100% in the fiber length range of 0 to 60 km, and 82.5% when the fiber length is 140 km. However, at 10 dB OSNR, the performance degrades more rapidly, with the PoCC dropping to 79% at 100 km.

The observed performance degradation beyond approximately 120 km can be attributed to three impairments: CD accumulation, nonlinear phase shift, and OSNR degradation. In standard single-mode fiber (SSMF), CD accumulates with distance and introduces pulse broadening, which distorts the received signal constellation. Nonlinear phase shift gradually accumulates as the length of the optical fiber increases and introduces additional phase perturbations to the modulated signal. In addition, OSNR gradually decreases because fiber attenuation and the EDFA introduces amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise, ultimately affecting the signal quality.

It is worth noting that the proposed system employs optical single-sideband (OSSB) modulation, which effectively mitigates CD fading compared with optical double-sideband (ODSB) modulation. By suppressing one optical sideband, OSSB avoids the strong frequency-selective fading caused by the interference between upper and lower sidebands in ODSB systems. As a result, it better preserves the amplitude and phase of the received RF signal over longer distances, improving robustness against CD-induced distortions and enabling more reliable classification.

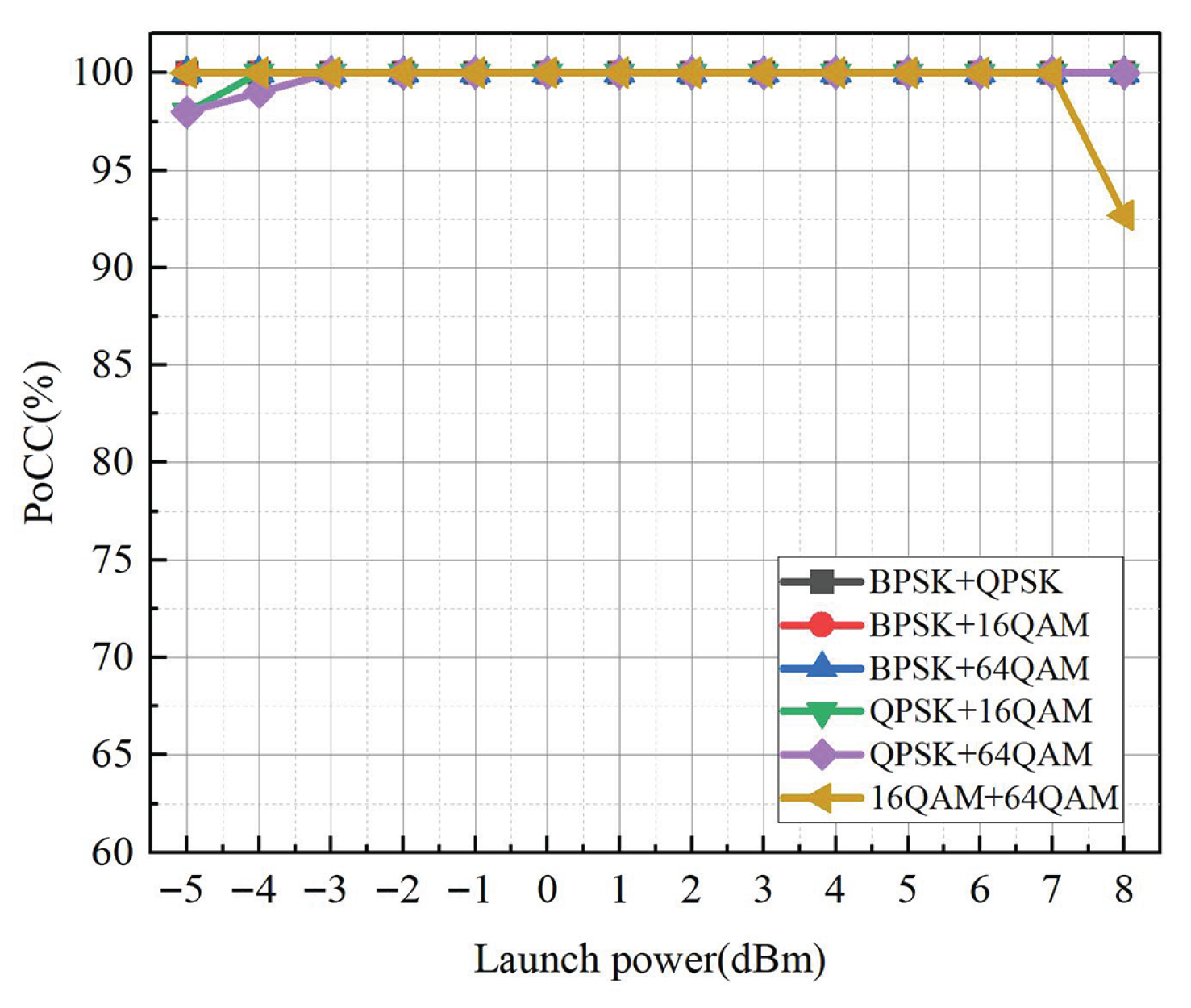

To further demonstrate the robustness of the proposed scheme towards nonlinear effects, the relationship between the PoCC and launch powers ranging from −5 dBm to 8 dBm of the mixed signals is shown in

Figure 15. The results indicate that the PoCC remains 100% for all mixed signals between −3 dBm and 7 dBm. However, at 8 dBm launch power, the PoCC for the 16QAM + 64QAM signal decreased to 92.7%, while the remaining five mixed signals maintained 100%. This outcome is anticipated, as higher-order modulation formats exhibit denser constellations that are more susceptible to nonlinear effects. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves excellent recognition over a wide range of launch power, exhibiting favorable robustness to nonlinearities.

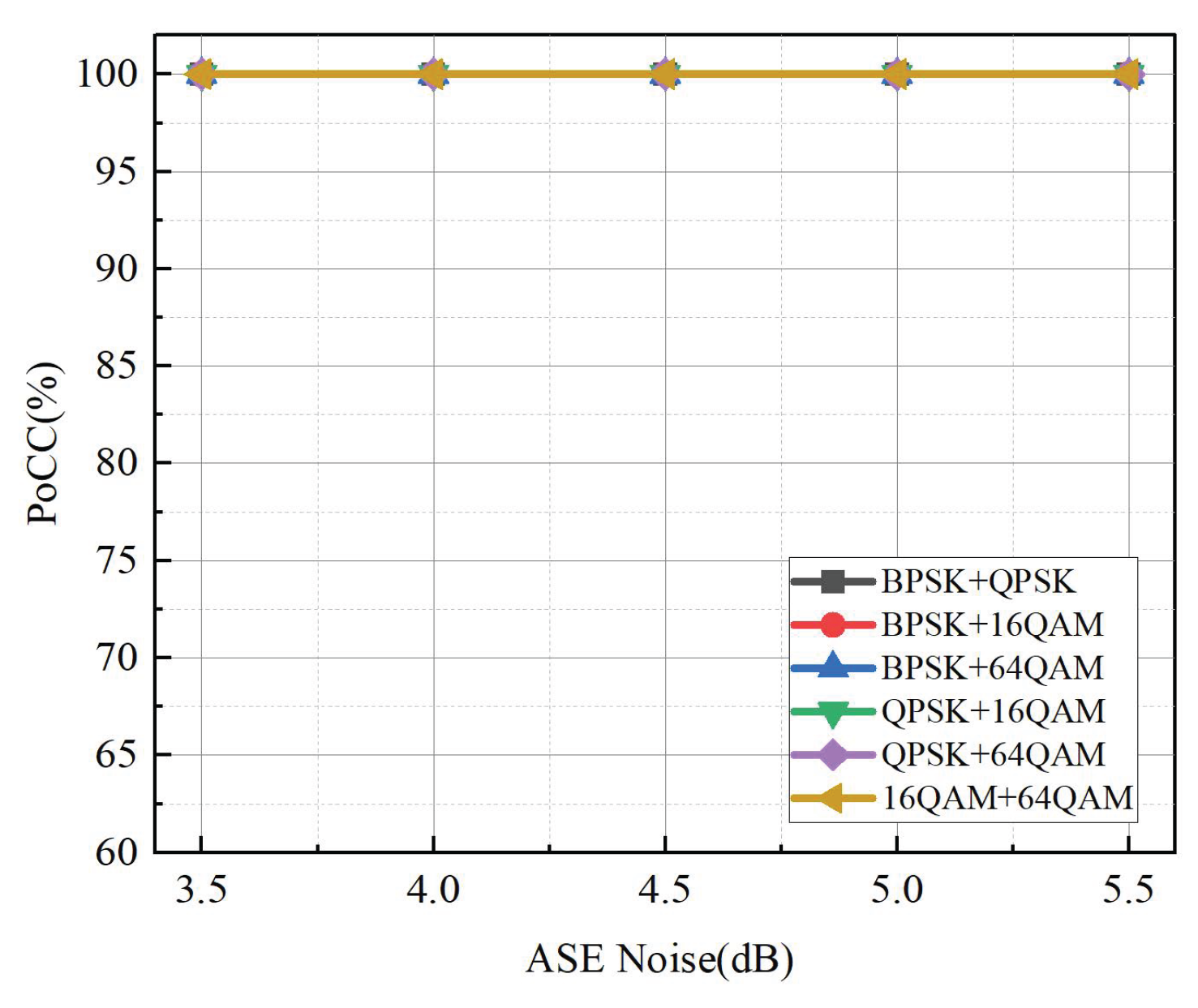

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed AMC scheme against ASE noise, the relationship between the PoCC and ASE noise variations for the six mixed signals is illustrated in

Figure 16. The ASE noise level is varied from 3.5 dB to 5.5 dB. The results indicate that the PoCC of all six mixed signals remains at 100% across the entire ASE noise range, demonstrating the strong robustness of the proposed method against ASE noise fluctuations.

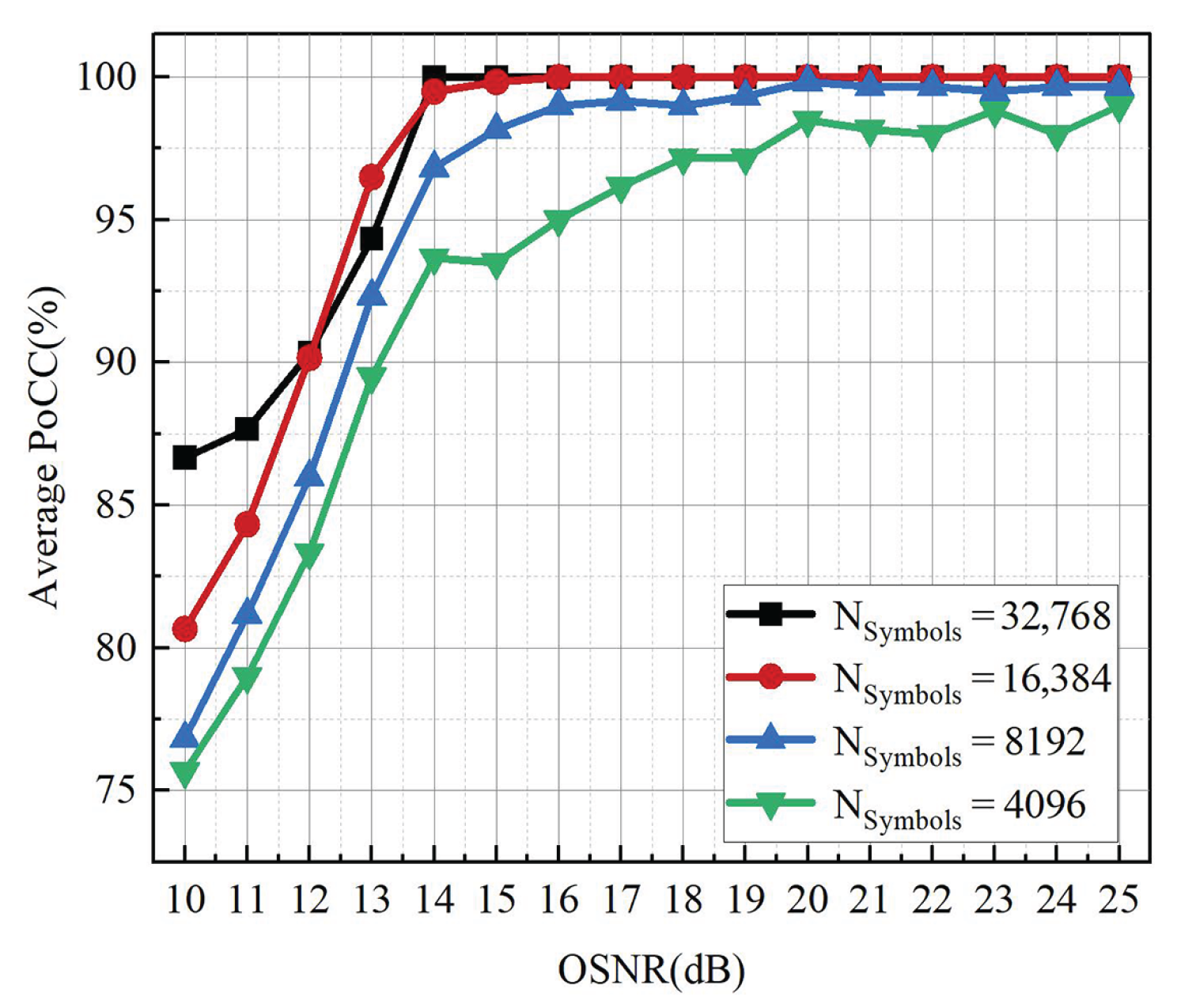

Figure 17 illustrates the impact of symbol numbers on the average PoCC of six mixed signals over a 70 km fiber link. Specifically, when the symbol numbers are 32,768 and the OSNR is ≥14 dB, the average PoCC of the six mixed signals reaches and stabilizes at 100%. With 16,384 symbols, the PoCC also achieves 100% when the OSNR is ≥16 dB. For 819 symbols, the PoCC reaches 99% at 16 dB and fluctuates around 99.5% for OSNR values above 20 dB. When the symbol numbers are further reduced to 4096, the PoCC decreases to 95% at 16 dB and only approaches a maximum of about 99% at 30 dB. These results clearly demonstrate that the numbers of symbols have a significant effect on recognition performance, with differences being particularly evident at lower OSNR levels.

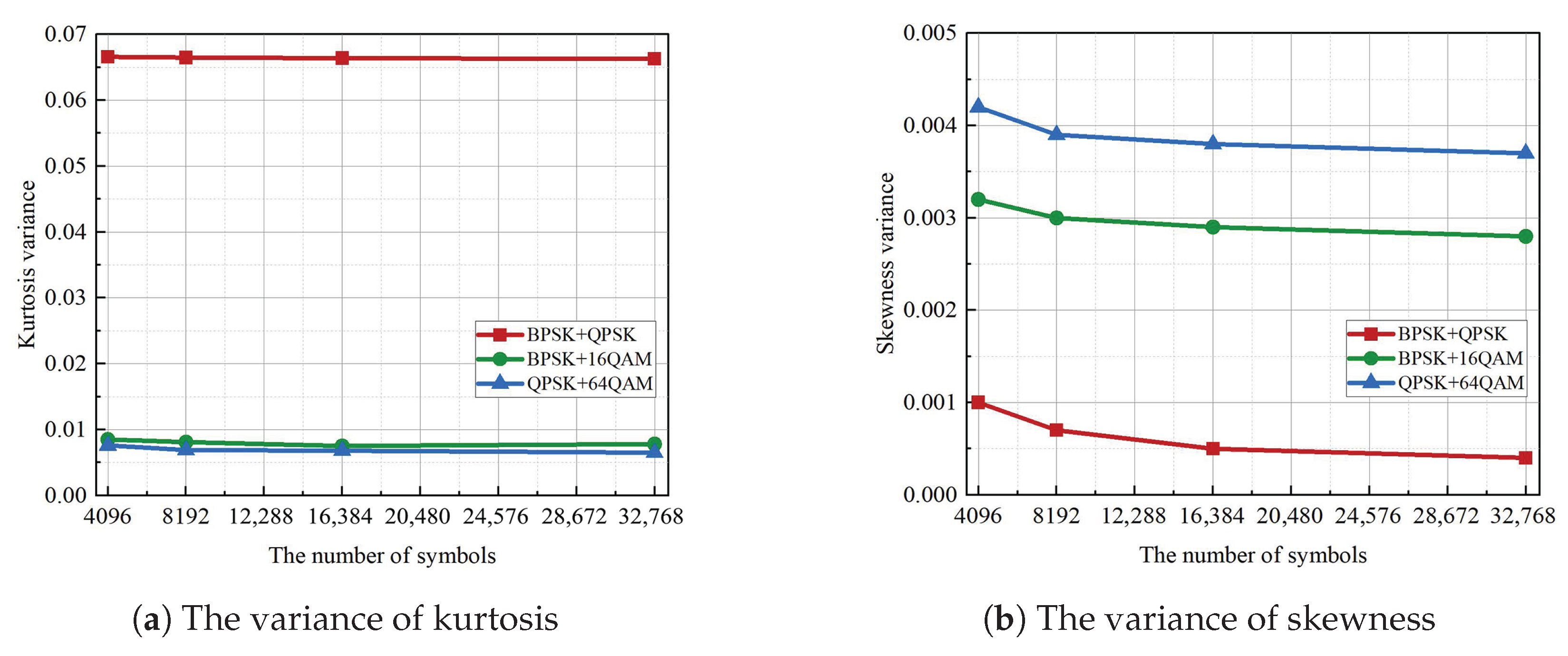

The improvement in the PoCC with increasing symbol numbers can be attributed to two main factors. First, a larger sample size effectively mitigates the influence of random noise and inter-signal interference, thereby reducing the variance of the PNI-HOC statistics. Second, when more symbols are used to estimate the amplitude distribution characteristics, these characteristics become more stable and distinct, which enhances the accuracy and robustness of feature extraction and ultimately improves the PoCC. Although employing 32,768 symbols provides slightly better performance than 16,384 symbols at certain OSNR values, the computational complexity of feature extraction increases approximately linearly with the number of symbols. To balance recognition accuracy and computational efficiency, 16,384 symbols are used in this work, which already ensures a stable PoCC of 100% when the OSNR exceeds 16 dB.

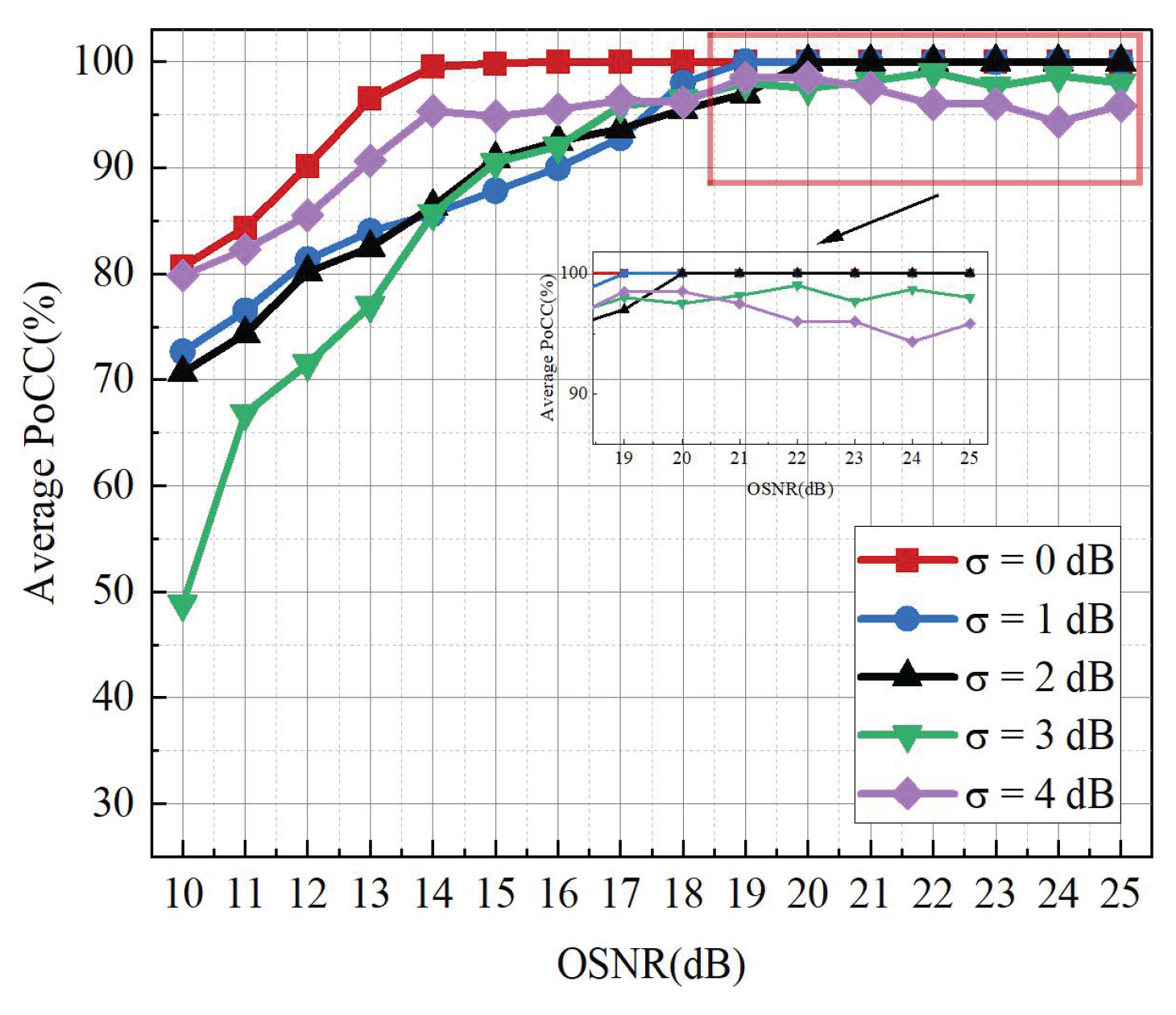

Figure 18 shows the average PoCC of mixed signals as a function of OSNR when the powers of

and

are unequal. The power difference, denoted as

, is set to 0 dB, 1 dB, 2 dB, 3 dB, and 4 dB. The results show that classification is optimal when the signals have equal power, with average PoCC remaining at 100% for OSNR ≥ 16 dB. For small power differences of 1 dB and 2 dB, the deviation in the

distribution is minor, and average PoCC maintains 100% for OSNR ≥ 19 dB and 20 dB, respectively. As the power difference increases to 3 dB and 4 dB, the higher-power signal dominates the statistical characteristics, which significantly weakens the amplitude information of the lower-power signal, causing larger deviation in the

distribution. In this case, average PoCC reaches approximately 95% at high OSNR, with maximum PoCC across the OSNR range of 98.7% and 98.5%. These results demonstrate that even under significant power imbalances, the proposed AMC method maintains reliable classification performance.

Although the proposed AMC scheme are evaluated through numerical simulations, the system architecture and parameter settings employed in this work are closely aligned with those used in practical experimental system. The simulation framework incorporates realistic device characteristics and fiber link impairments, thereby ensuring that the modeled system behavior is representative of an actual experimental environment. This alignment supports the practical feasibility of implementing the proposed scheme beyond simulation. In our future work, we plan to further validate the proposed scheme under actual transmission conditions.

5. Complexity Analysis

To assess the feasibility of the proposed AMC algorithm in practical systems, its computational complexity is analyzed. The overall complexity consists of two stages: feature extraction and classification. In the feature extraction stage, the complexity of the traditional high-order cumulant algorithm is O(N), where N is the number of signal samples. The introduced phase noise correction term has a complexity of O(1). Therefore, the overall complexity of the proposed PNI-HOC algorithm is O(N). The subsequent extraction of amplitude histogram characteristics, specifically kurtosis and skewness, also has a complexity of O(). In the classification stage, the decision operation simply compares the PNI-HOC values to corresponding thresholds, resulting in a complexity of O(1). For the SVM classifier using the RBF kernel, the theoretical time complexity of the training process is approximately O(m3), where m is the number of training samples. However, the training process is an offline stage and does not affect the online recognition in practical applications. The dimension of the testing process is approximately O(s*d), since O(s*d) is at the constant level (d = 2, s is the number of finite support vectors), it can be ignored. Therefore, the overall online complexity of the proposed scheme remains O().

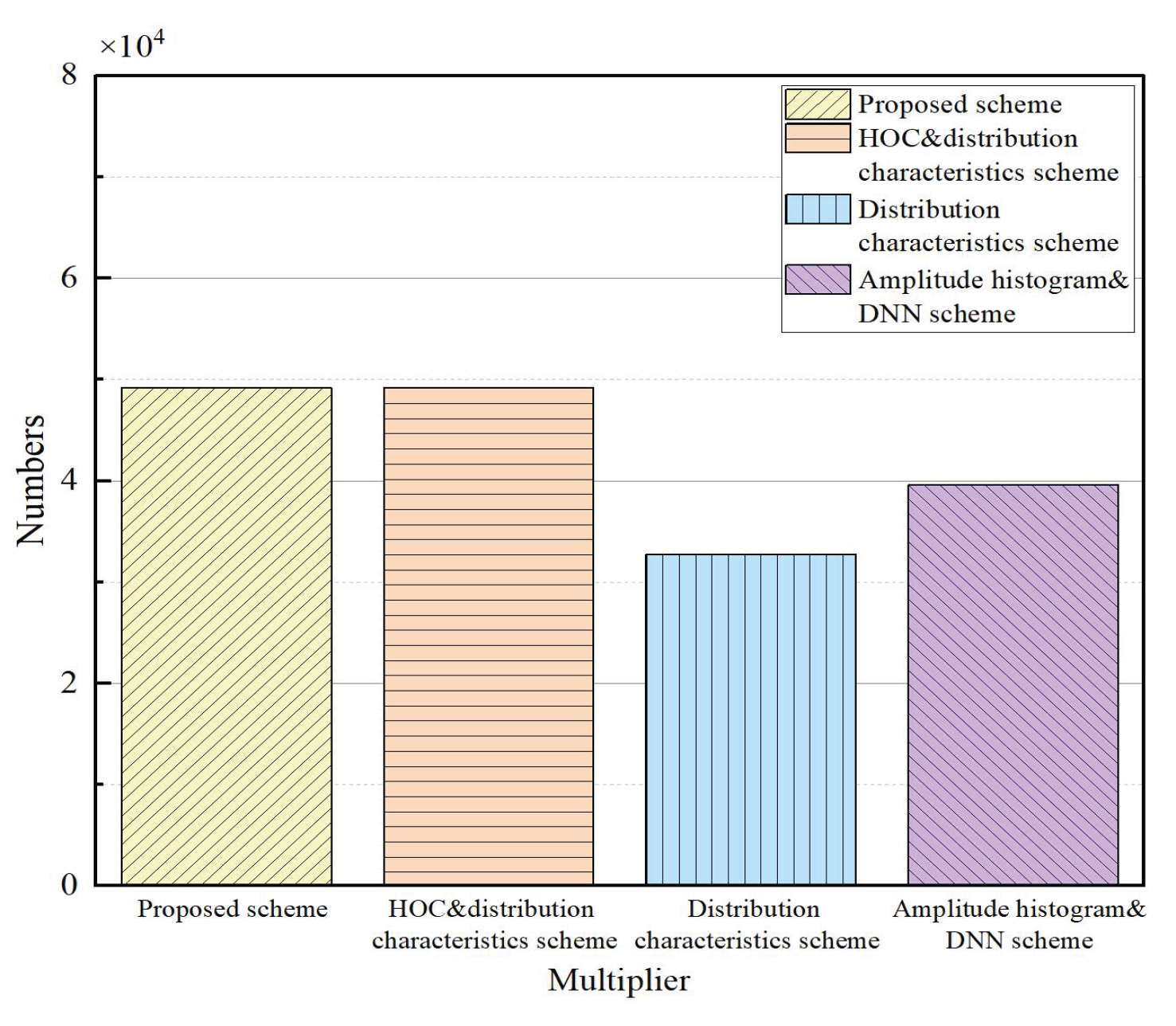

To further evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed algorithm, a comparative analysis of computational complexity among several schemes is conducted under the same sample length

N = 16,384. The complexity comparison chart is shown in

Figure 19. The traditional HOC combined with distribution characteristics and the proposed PNI-HOC combined with distribution characteristics require

= 49,152 multiplications, since the phase noise correction in PNI-HOC adds only constant-order operations. When only distribution characteristics are used, the multiplication complexity is reduced to

, i.e., 32,768 multiplications. For the scheme combining amplitude histograms with DNN classification, the complexity includes histogram generation and the forward computation of DNN. With the network configuration

= 128,

= 64,

= 32, and C = 6, the DNN requires

= 128,

= 64,

= 32, and C = 6, where B is the number of histogram bins, while

,

,

and C represent the number of neurons in the first hidden layer, the second hidden layer, the third hidden layer, and the output layer, respectively. Thus, the total multiplication count becomes

N + (100 × 128 + 128 × 64 + 64 × 32 + 32 × 6), which equals 39,616.

These results show that the proposed PNI-HOC scheme maintains the same online computational order as the traditional HOC algorithm while substantially improving robustness under severe phase noise. Compared with both the scheme based on distribution characteristics and the DNN-based approach, it achieves higher recognition accuracy with only minimal additional computational cost. In future work, we will continue to explore strategies that further reduce implementation complexity.