1. Introduction

Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are flying vehicles capable of executing flight missions without the need for a human pilot. Initially, they were designed for military purposes [

1], such as reconnaissance, surveillance, and combat. However, the recent development of low-cost, high-efficiency, and highly mobile UAVs [

2] has broadened their use across numerous civil and industrial fields [

3], including agricultural irrigation [

4], forestry detection [

5], ocean monitoring [

6], topographic mapping [

7], cargo delivery [

8], rescue missions [

9], and traffic planning [

10]. Autonomous UAVs are particularly desirable for replacing humans in high-risk, long-duration, or precision-critical operations.

A UAV system typically consists of three main subsystems: the sensing subsystem, the path planning subsystem, and the execution subsystem. Among them, the path planning module acts as the “brain” of the UAV, enabling autonomous navigation by computing feasible and collision-free routes based on sensor feedback. Given a defined start and goal position, an efficient path planning algorithm determines a trajectory that satisfies mission-specific optimization criteria [

11]—for instance, minimizing time, distance, or energy consumption. However, real-time path planning often imposes heavy computational demands on onboard embedded systems, leading to increased power consumption and reduced flight endurance.

Classical and intelligent path planning algorithms have been extensively studied to mitigate this challenge [

12]. Early approaches such as the Dijkstra algorithm provided optimal shortest paths but suffered from high computational costs. The A* algorithm improved upon this by introducing heuristic functions for faster convergence; nevertheless, it still required substantial memory and computation time [

13,

14]. The potential field method introduced by Khatib [

14] employed attractive and repulsive forces to navigate around obstacles, and subsequent studies—such as the bacterial potential field [

15] and multi-degree potential field methods [

16]—sought to overcome the local minimum problem.

In contrast, the Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithm offers a more computationally feasible alternative. Originally designed for high-dimensional motion planning, RRT is recognized for its efficient space exploration and low complexity. Yet, its paths are often irregular and discontinuous, which limits their suitability for smooth flight trajectories. The RRT* algorithm proposed by Karaman and Frazzoli [

17] addressed part of this issue by improving asymptotic optimality, leading to widespread adoption in robotic and UAV applications [

18].

Recent advancements continue to refine RRT-based frameworks for dynamic and resource-constrained systems. For example, Zhao et al. [

19] proposed the Dynamic RRT algorithm, which balances convergence time and path length when planning feasible paths in environments with randomly distributed obstacles, while Dong et al. [

20] employed a hybrid PSO–RRT planner to generate collision-free three-dimensional UAV trajectories in complex low-altitude urban airspace. Despite these innovations, most implementations assume powerful onboard processors or external computation units, which are often impractical for lightweight UAVs using low-power embedded hardware.

To bridge this technological gap, this study presents the design and implementation of an improved RRT algorithm on an STM32-based onboard embedded system, emphasizing low-power computation and real-time feasibility. Unlike simulation-only approaches, our work performs all path planning tasks—including path pruning, Bézier curve smoothing, and iterative optimization—directly on a 32-bit STM32 microcontroller. To manage computational constraints, the UAV’s navigation task is formulated as a 2.5D path planning problem, where trajectory generation occurs on the horizontal plane with altitude stabilized via the flight controller’s barometric feedback. This simplification enables efficient onboard computation without sacrificing trajectory accuracy. The subsequent sections detail the system implementation, algorithmic optimization, and in-flight validation results, confirming the viability of executing a refined RRT-based path planner entirely within a constrained embedded UAV platform.

This study aims to bridge the gap between theoretical path planning algorithms and their practical implementation on computationally limited onboard embedded systems. The primary contribution of this work is not the introduction of a novel algorithm, but the successful adaptation, optimization, and in-flight validation of an enhanced RRT-based framework implemented directly on a 32-bit STM32 microcontroller. To effectively balance computational complexity, memory footprint, and power efficiency, the navigation problem is formulated as a 2.5D path planning model, where trajectory generation is conducted on a two-dimensional plane at a fixed altitude. Altitude stability is independently maintained by the flight controller’s onboard barometer, enabling the computationally intensive RRT–Bézier hybrid planner to focus exclusively on the XY-plane. The following sections describe the detailed algorithmic design, onboard optimization strategies for low-power computation, and the experimental validation results that confirm the feasibility of achieving autonomous flight using a constrained STM32-class embedded platform.

This architectural choice intentionally prioritizes computational stability and energy efficiency over sub-second responsiveness. By constraining the planner to a 2.5D formulation and accepting a planning latency of approximately 0.958 s per cycle, the system achieves a practical balance between low-power embedded execution and long-endurance flight in static ground-obstacle environments. This represents a deliberate engineering trade-off rather than a limitation of the RRT algorithm itself.

2. An Improved RRT Algorithm

In this study, the term ‘Improved RRT’ refers to a hybrid architectural optimization specifically designed for constrained embedded systems, rather than a modification of the fundamental sampling theory. While algorithms like RRT* provide asymptotic optimality, their ‘rewiring’ operations are computationally expensive and memory-intensive for microcontrollers with limited SRAM (e.g., 20 KB on STM32F103). Therefore, our proposed framework integrates the standard RRT for rapid exploration with a lightweight post-processing pipeline: Greedy Path Pruning and Golden-Ratio Bézier Smoothing. This approach shifts the computational burden from global tree optimization to local path refinement, ensuring real-time feasibility without exceeding hardware memory limits.

Rapidly-Exploring Random Trees (RRT) in a matrix space (S) plans a route from a starting point (Sstart, Sstart ⊂ S) to a destination (Sdest, Sdest ⊂ S) by exploring the free space (Sfree, Sfree ⊂ S), and avoids obstacles (Sobst, Sobst ⊂ S). Both Sstart and Sdest are points in this three-dimensional space. The RRT algorithm starts with Sstart and generates a random sampling point (Srand, Srand ⊂ S) in the matrix space to search for the node which is nearest the Srand in the tree as Snear (Snear, Snear ⊂ S).

S

near then extends a shortest distance based on Euclidean distance toward S

rand as a new node S

new and ensures the distance is limited in every expansion. When S

near ⊂ S

free and does not intersect with S

obst, S

new will be added into the tree and repeating the process until it reaches the destination.

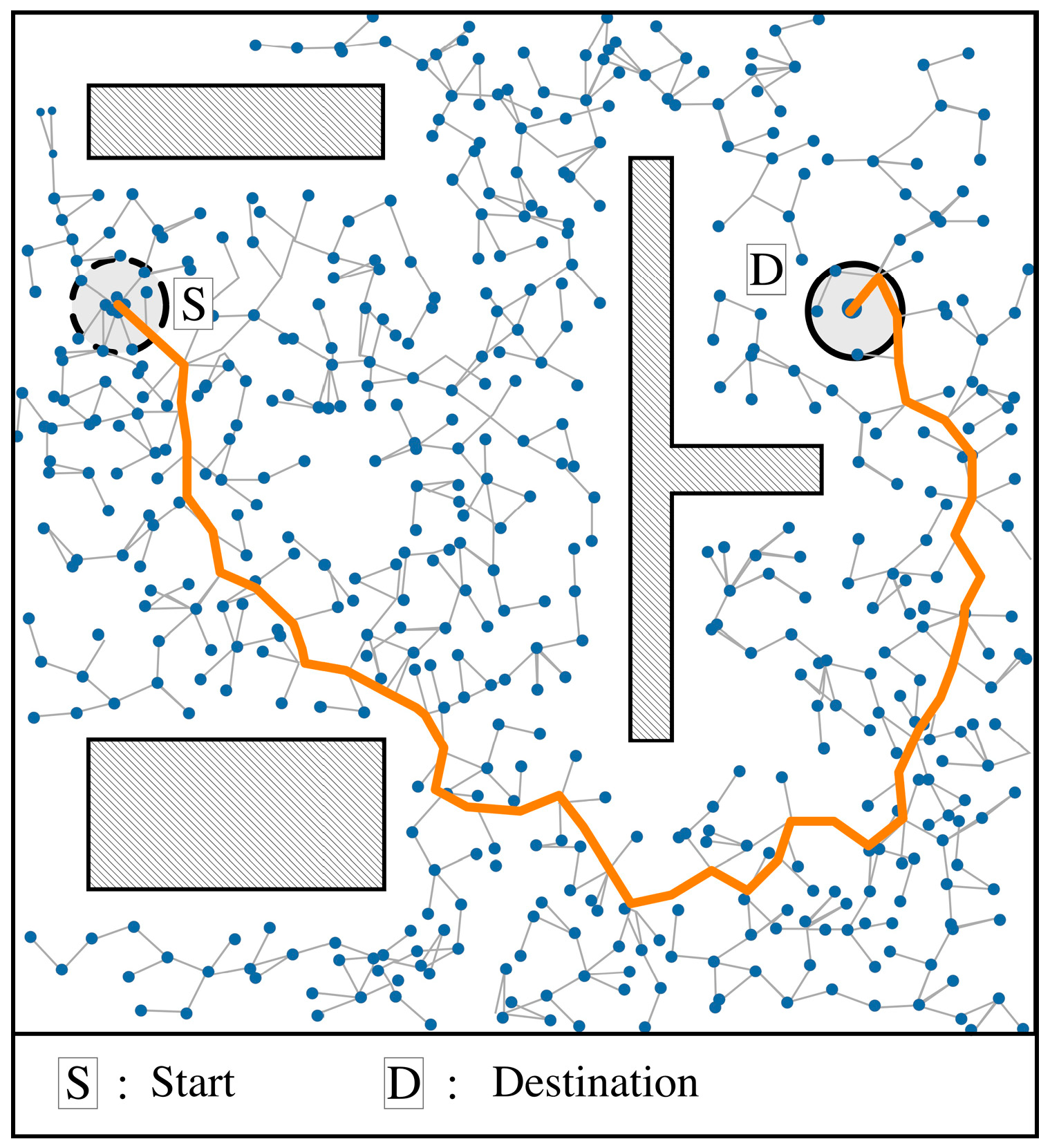

Figure 1 illustrates a save path generated by RRT algorithm. Because of the randomness of the path, many redundant turning points will be produced during the process, which could lead to inefficient path planning.

2.1. Pruning and Obstacle Detection

Since the paths generated by the RRT algorithm are often zigzag and difficult for UAVs to execute, path pruning is thus essential. The pruning process is illustrated in

Figure 2. By removing unnecessary points, a collision-free path can be produced. Starting with the initial point, three consecutive points are chosen for pruning. If the first and third nodes can be connected without colliding with any obstacles, the second node is redundant and will be removed. Otherwise, the second node is retained. This process continues until the shortest path is achieved. As illustrated in

Figure 2a, when considering points

P1,

P2, and

P3, connecting

P1 and

P3 results in a collision with the obstacle; so,

P2 must be retained. However, when considering points

P3,

P4, and

P5, connecting

P3 and

P5 results in no collision, making

P4 redundant and eligible for pruning. During the pruning process, removing redundant nodes shall generate a more efficient path, as shown in

Figure 2b.

In path planning, it is necessary to detect collisions to determine whether the path between two points intersects with any obstacles. Polygonal modeling for collision detection is usually complex, time-consuming, and computationally intensive. Simplifying the geometry of obstacles can improve efficiency. The boundaries of obstacles can be set as rectangular by a distance d

s, where d

s is half of the UAV’s width, as shown in

Figure 3a. During collision checking, if both points are on the same side of the obstacle, as shown in

Figure 3b, the path is safe. Otherwise, further verification is required by the conditions:

where

Aco1 and

Aco3 are the angles between

P1 and the edge of obstacle, and

Acp is the angle of the path between two check points. Equation (1) indicate

P1 is on the left side of the obstacle, and Equation (2) indicate

P3 is on the right side of the obstacle, as shown in

Figure 3c. This detection ensures any point on the path will not collide with the obstacles. After pruning and obstacle detection, the number of nodes decrease significantly by about 99%. This pruning not only shortens the path length but also reduces the number of turning points.

2.2. Smoothing and Optimization

After pruning, a more concise path is obtained, as shown in

Figure 2b. However, the path is not continuously differentiable, thus may reduce the navigation efficiency. Bézier curves are applied to make the path continuously differentiable. One advantage of Bézier curves is their low computational cost, allowing UAVs to avoid obstacles while maintaining kinematic feasibility. A Bézier curve requires only three control points to generate a transition curve that connects two line-segments [

21]. Bézier curves have also been used for collision-free path planning in lane-change maneuvers [

22] and vehicle tracking [

23]. The equation of a quadratic Bézier curve is

where

Pi+1 is the control points of Bézier curve and

is

A quadratic Bézier curve (

n = 2) requires three control points. To define these, set the first control point at the turning point, and move forward and backward along the path for a specific distance to determine the other two control points. This specific distance is based on the golden ratio 0.382 (by Fibonacci number) to the length of the line segment. Two sets of control points are shown in

Figure 4a, and the resulting smooth Bézier curve is obtained after calculation, as shown in

Figure 4b. Low-order Bézier curves offer excellent efficiency with minimal computational cost.

The choice of the 0.382 ratio, instead of a symmetric midpoint at 0.5, is motivated by the golden-section principle. Placing the control points at the golden section helps to distribute curvature more evenly along the quadratic Bézier transition, thereby reducing abrupt heading changes and instantaneous jerk during turns. In our experiments, this setting produced smoother yaw profiles and maintained a safer lateral clearance from nearby obstacles compared with symmetric control-point placement. As a result, the low-order Bézier smoothing achieves both computational simplicity and practically adequate kinematic feasibility for embedded flight control. The pseudocode of the improved RRT pipeline—including standard RRT exploration, greedy path pruning, and golden-ratio Bézier smoothing—is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Improved RRT for Embedded UAV |

Input: Start, Goal, Map, Max_Iterations = 10

Output: Optimized_Path

1: Best_Path_Cost ← Infinity

2: Best_Path ← NULL

3: for i ← 1 to Max_Iterations do

4: // Stage 1: Standard RRT (Low Memory Usage)

5: Raw_Path ← Run_Standard_RRT(Start, Goal, Map)

6: if Raw_Path is found then

7: // Stage 2: Greedy Pruning (Local Optimization)

8: Pruned_Path ← Greedy_Prune(Raw_Path)

9: Cost ← Calculate_Cost(Pruned_Path)

10: if Cost < Best_Path_Cost:

11: Best_Path_Cost = Cost

12: Best_Path = Pruned_Path

13: end if

14: Clear_Memory() // Crucial for limited SRAM

15: end if

16: end for

17: if Best_Path == NULL then

18: return FAILURE

19: end if

20: // Stage 3: Kinematic Smoothing

21: Final_Path ← Bezier_Smoothing(Best_Path, Ratio = 0.382)

22: return Final_Path |

As shown in Algorithm 1, the control points are placed at 38.2% and 61.8% along each adjacent segment, which corresponds to the golden-section ratio. The randomness of the RRT algorithm allows it to find the paths in a complex space, and there are often multiple possible paths. The path could extend upward or downward, as shown in

Figure 5a, where the downward path is clearly inefficient. Therefore, it is crucial to discover the nearest or shortest path. By repeating the path planning process, the shortest path can be identified.

Table 1 lists the success rate of finding the shortest path and the computation time when repeating the path planning process 1, 5, and 10 times. The success rate for a single execution is 56%, requiring 0.09 s. The success rate for 5 repeated path planning is 74% with computation time of 0.42 s. For 10 path planning, the success rate increases to 96%, requiring 0.9 s. These results indicate that increasing the number of repeated planning improves the success rate of finding the shortest path. With advancements in chip technology (STM32) as described in the coming section, this result is acceptable.

Figure 5b shows that, after repeating the planning process 10 times, the shortest path for the autonomous UAV can be found.

The results show that after pruning and optimization as illustrated in

Figure 5b, the path length decreases approximately by half, significantly increasing flight efficiency. Path length can be viewed as an indicator of the effectiveness of path planning.

The choice of 10 repetitions is a deliberate engineering trade-off between path optimality and system latency. As summarized in

Table 1, increasing the number of planning runs from 1 to 10 raises the success rate of finding a shortest-path candidate from 56% to 96%. In principle, running 100 iterations could further reduce the path cost; however, it would also increase the planning latency to roughly 9 s, which is incompatible with the real-time operational constraints of the UAV. Consequently, 10 iterations (approximately 0.90 s in total) represent a practical operating point where the planner achieves statistically reliable performance within a one-second time budget.

The data indicates that the original path length generated by the RRT algorithm is 1043 units. After pruning, the path length is reduced to 776 units, a 34% decrease. Following curve fitting, the path length is further reduced to 583 units, another 33% reduction compared to the pruned path.

Figure 6 illustrates the paths generated by the improved RRT algorithm in environments with various obstacles. It is evident that this improved algorithm provides an efficient and safe path for UAVs.

2.3. Onboard Implementation Challenges and Optimizations

Porting the refined RRT framework from a desktop environment to a resource-constrained microcontroller such as the STM32F103C8T6 introduces several practical challenges. The available hardware resources are limited to 20 KB of SRAM, 64 KB of Flash, and a 72 MHz ARM Cortex-M3 core without a floating-point unit (FPU). Under these constraints, both memory management and arithmetic efficiency become critical design considerations.

To ensure deterministic memory behavior, all RRT nodes are allocated from a statically defined memory pool instead of using dynamic allocation (e.g., malloc). Each node stores its Cartesian coordinates, parent index, and cost value in 16-bit precision, leading to an effective memory usage of roughly 12 bytes per node when auxiliary bookkeeping variables are included. Accounting for additional system buffers, the usable memory budget for the tree is approximately 18 KB, which translates to a maximum node capacity of about Nmax ≈ 1500 nodes. Once this limit is reached, tree expansion is halted, guaranteeing that the planner never exceeds the SRAM capacity and avoiding fragmentation over long missions.

Arithmetic operations were also carefully optimized. In distance and collision-checking routines, comparisons are performed on squared Euclidean distances to avoid expensive square-root computations. The firmware is compiled with high-level optimizations (−O3), which reduces the instruction count and improves throughput on the Cortex-M3 pipeline. Together, these optimizations are essential for enabling the complete three-stage planner—tree generation, path pruning, and Bézier smoothing—to execute reliably within the timing and energy budgets of the STM32-based onboard platform.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the quantitative results from the in-flight validation experiments. The performance of the onboard planner is evaluated in terms of trajectory tracking accuracy, computational efficiency on the STM32 microcontroller, and a comparative analysis of its power consumption and positioning within the broader landscape of path planning algorithms.

4.1. Flight Trajectory Validation

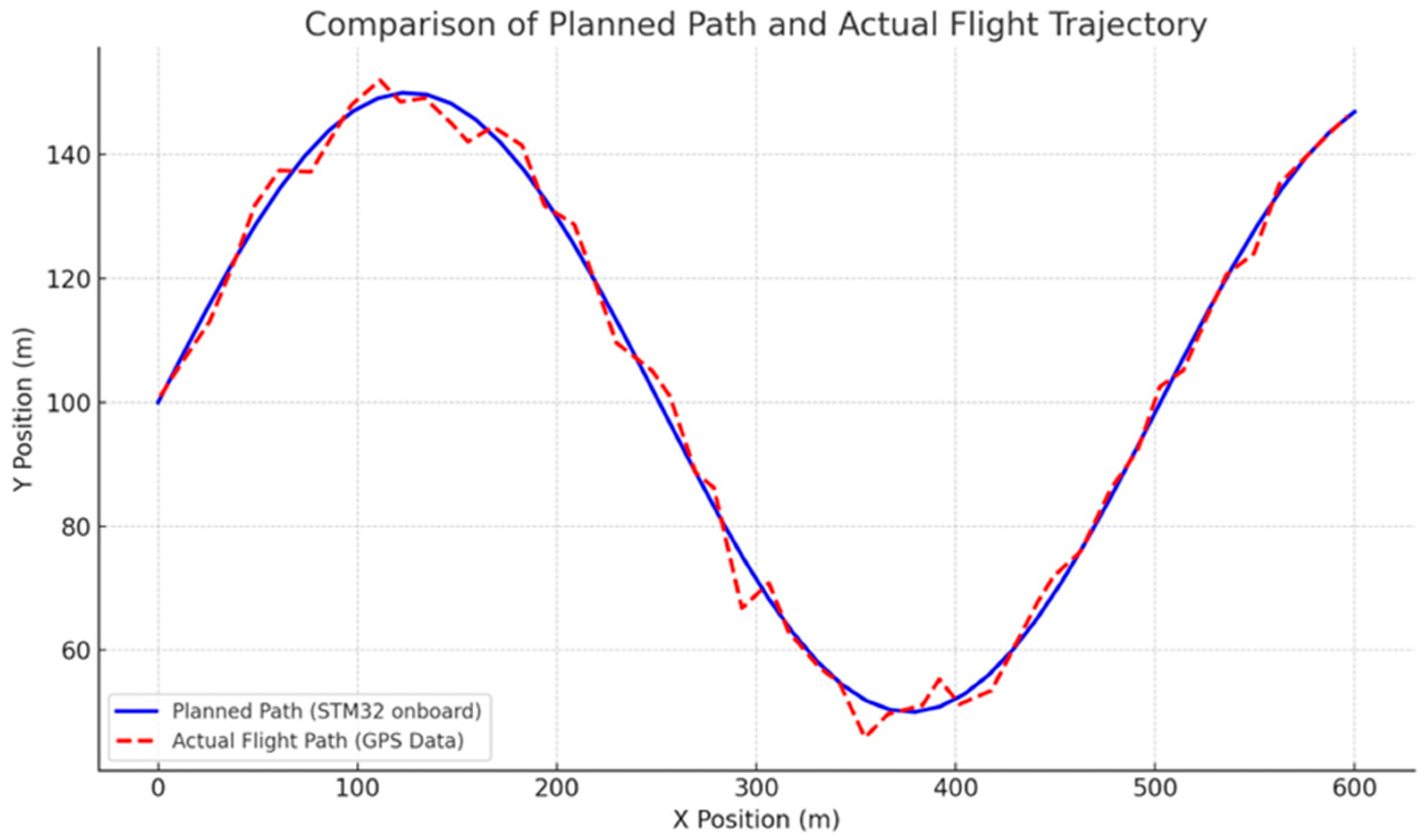

To validate the system’s real-world effectiveness, the planned path generated by the STM32 was executed by the UAV, and the actual flight trajectory was recorded via GPS telemetry.

Figure 11 provides a visual comparison between the optimized path computed onboard and the actual trajectory flown by the UAV. The figure clearly shows that the UAV closely followed the planned route, with only minor deviations attributed to wind disturbances and waypoint-tracking latency. This confirms the robustness of the proposed planner in maintaining trajectory accuracy under real-world flight conditions.

A quantitative analysis of the flight performance is presented in

Table 2. The experiment was repeated five times to ensure statistical reliability, and the presented values are the averages of these runs. The results show a high degree of correspondence between the planned and executed paths, with an average tracking error of only 1.25 m.

The discussion of these results reveals several insights. The slight increase in actual path length and flight time can be attributed to external factors such as wind gusts and the inherent limitations of the lower-layer flight controller’s PID loop in perfectly tracking waypoints. The average tracking error of 1.25 m is well within the expected tolerance for a standard civilian GPS module and confirms that the generated path is not only collision-free in theory but also safely executable in practice.

4.2. Power Consumption and Comparative Analysis

A key claim of this study is the real-time capability of the planner on the STM32 platform. To substantiate this, the execution time of each stage of the algorithm was measured directly on the microcontroller using its internal timers.

Table 3 details the average processing time required for a complete planning cycle, based on 10 optimization runs as described in

Section 2.2.

The total planning time of just under one second is a critical result. While this may not be sufficient for highly dynamic environments requiring sub-second replanning, it is perfectly acceptable for pre-flight mission planning in static or semi-static environments, which was the target application for this study. This performance benchmark validates that the STM32 microcontroller, despite its constraints, possesses adequate computational power for this complex task, directly addressing the critique of insufficient computational analysis.

4.3. Onboard Computational Performance

The choice of the STM32 was motivated by its low power consumption. During the planning phase (full computational load at 72 MHz), the current drawn by the STM32F103C8T6 was measured to be approximately 30 mA at a supply voltage of 3.3 V, resulting in a power consumption of about 99 mW. This is significantly lower than more powerful single-board computers like a Raspberry Pi, which can consume several watts, making our approach highly suitable for battery-powered UAVs where endurance is paramount.

To contextualize the contribution of this work,

Table 4 provides a comparative analysis against other state-of-the-art RRT-based methods based on literature. This comparison highlights the trade-offs between algorithmic optimality, environmental adaptability, and hardware feasibility.

This analysis makes the contribution of our paper clear: while other methods achieve higher levels of path optimality or adaptability, they do so at the cost of computational resources that make them unsuitable for direct implementation on low-cost microcontrollers. Our work fills a crucial gap by demonstrating a complete, validated solution that prioritizes resource efficiency and practical embeddability, thereby confirming the viability of advanced path planning on hardware platforms that are accessible and widely used in the UAV industry.

To summarize the key performance indicators and highlight directions for future optimization,

Table 5 consolidates the main metrics discussed in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3, including success rate, path length, planning latency, and energy consumption.

5. Conclusions

This paper has successfully demonstrated the practical implementation and in-flight validation of a refined RRT-based path-planning framework on a UAV platform equipped with a resource-constrained STM32 microcontroller. The primary contribution of this work is not the development of a novel algorithm but rather a comprehensive engineering case study that confirms the feasibility of executing a sophisticated multistage planning process—including path pruning, Bézier-curve smoothing, and iterative optimization—entirely within an onboard embedded system.

Our experimental results provide clear evidence that the system is effective in real-world conditions. The UAV autonomously computed and accurately followed collision-free trajectories in an environment with static ground obstacles. By framing the navigation task as a 2.5D path-planning problem, in which trajectory generation is performed on a two-dimensional plane while altitude is maintained by an onboard barometer, the computational workload was effectively contained within the low-power STM32 processor. The resulting planning latency of approximately 958 ms per cycle represents an intentional balance between computational stability, energy efficiency, and operational endurance. This latency is a deliberate engineering trade-off designed for low-power, long-duration missions rather than a limitation of the RRT algorithm itself. Consequently, the framework demonstrates that even with constrained hardware resources, a high degree of autonomous capability can be achieved.

Looking forward, the current system serves as a robust foundation for future enhancements. Its present limitation lies in the reliance on a predefined static map. The next logical step is to integrate real-time environmental-perception sensors, such as cameras or LiDAR, to enable dynamic obstacle detection and avoidance. This evolution would transition the current planner from a purely deliberative framework into a reactive and adaptive onboard system, thereby extending its applicability to more complex and uncertain operational scenarios while maintaining its low-power and high-endurance design philosophy.