Multimodal Mutual Information Extraction and Source Detection with Application in Focal Seizure Localization

Abstract

1. Introduction

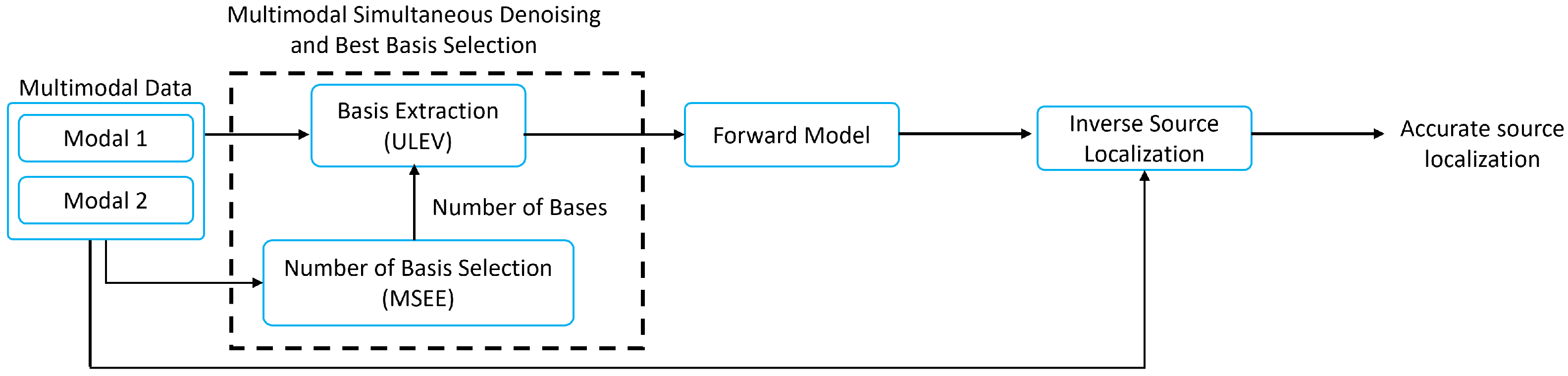

2. Multimodal Information Extraction and Source Localization (MieSoL)

2.1. Multimodal Information Extraction (Mie)

2.1.1. Basis Extraction: Unified Left Eigenvectors (ULeV)

2.1.2. Number of Basis Selection: Mean Squared Eigenvalue Error (MSEE)

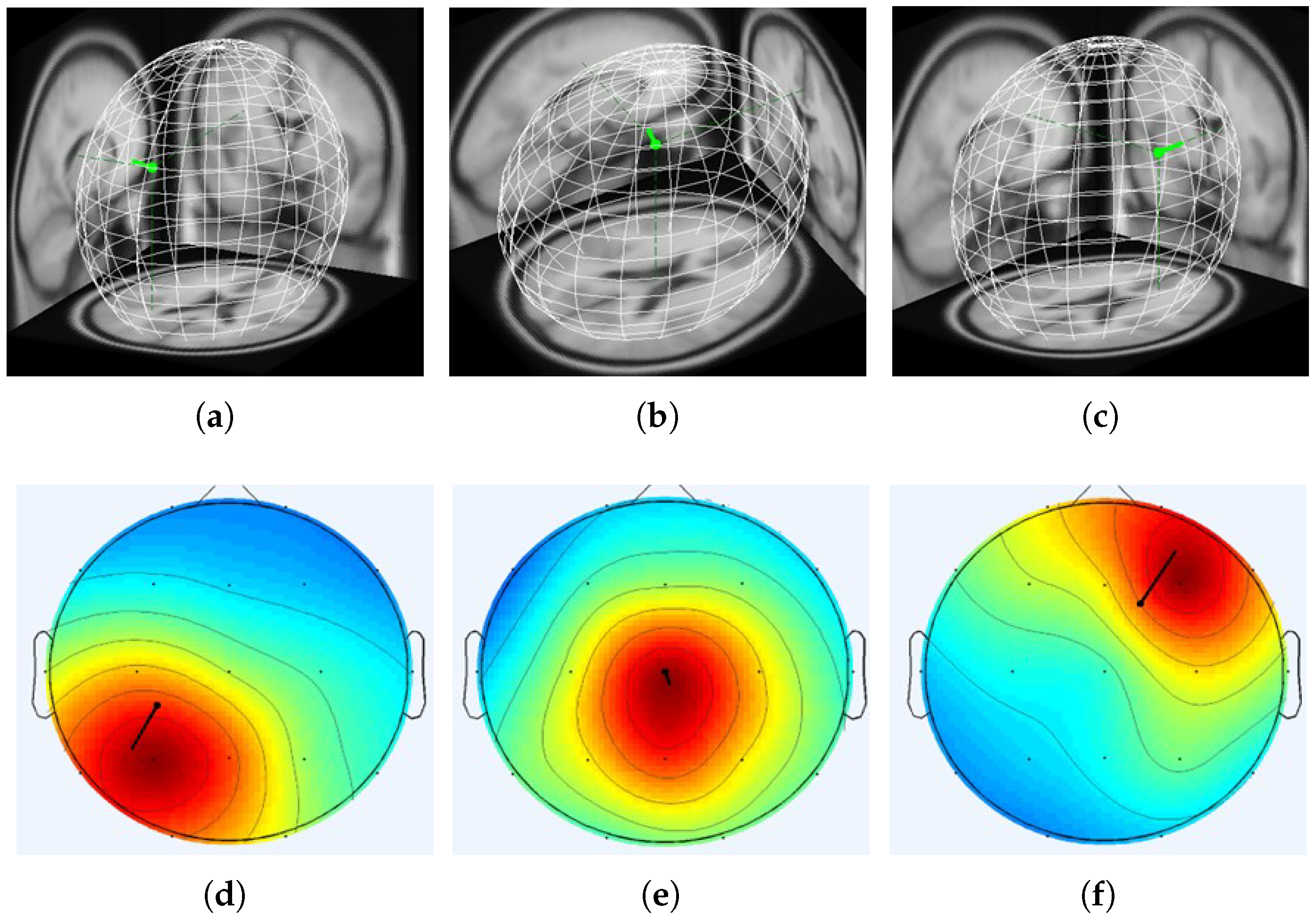

2.2. Efficient Source Localization (ES)

2.2.1. Forward Model

2.2.2. Source Localization: Efficient High-Resolution sLORETA (EHR-sLORETA)

3. Simulation and Results

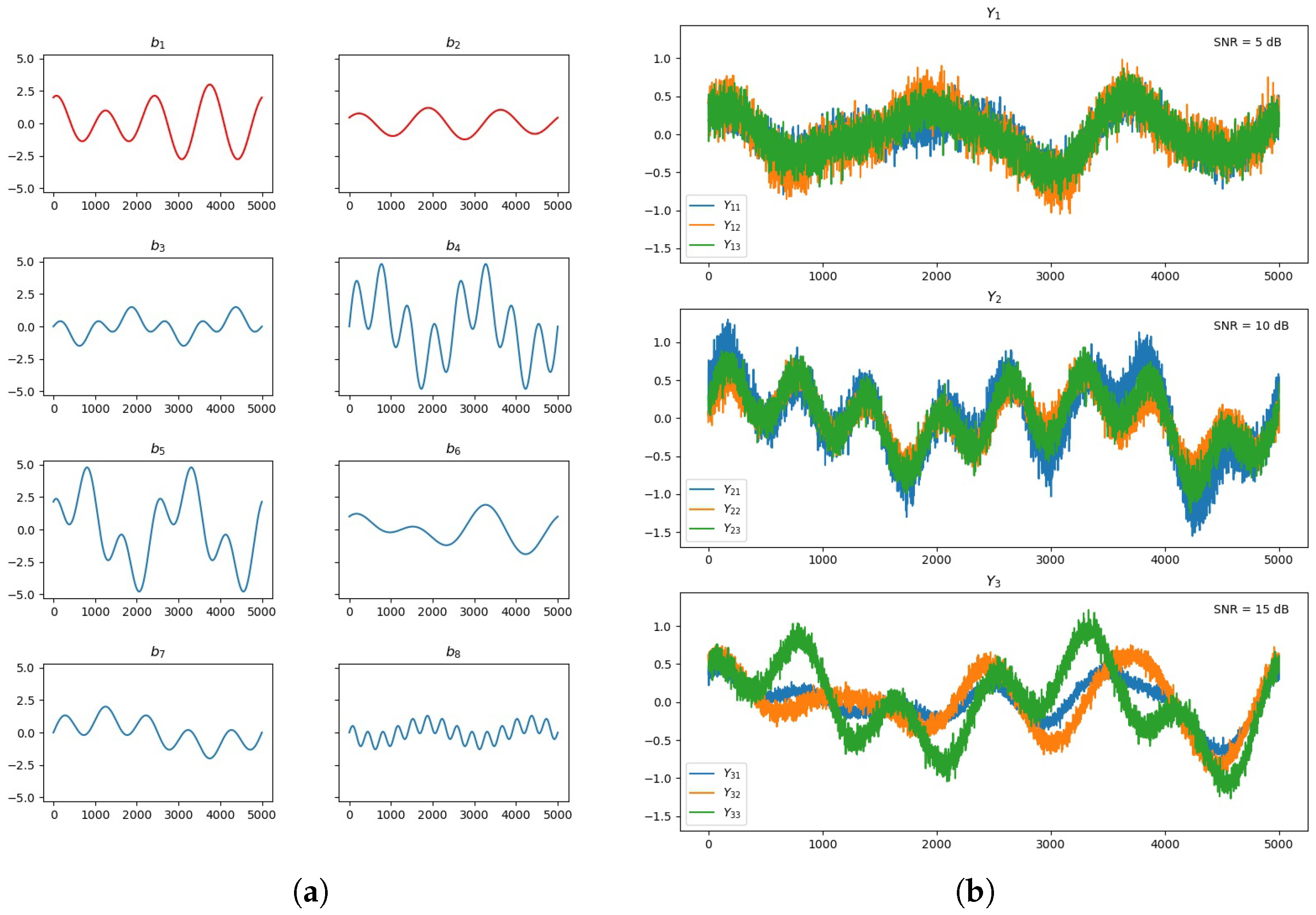

3.1. Multimodal Information Extraction Testing

3.2. Synthetic EEG and MRI Data

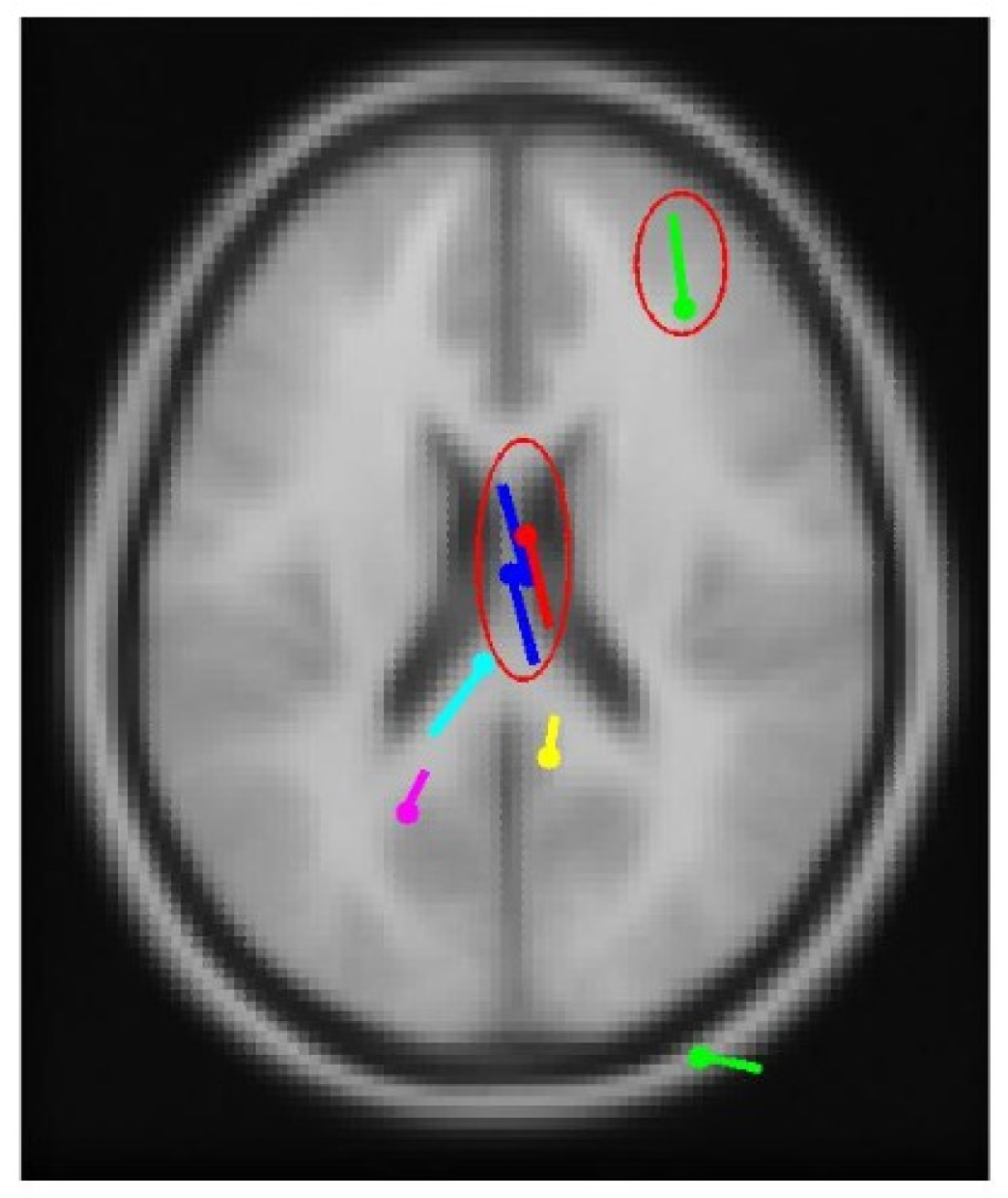

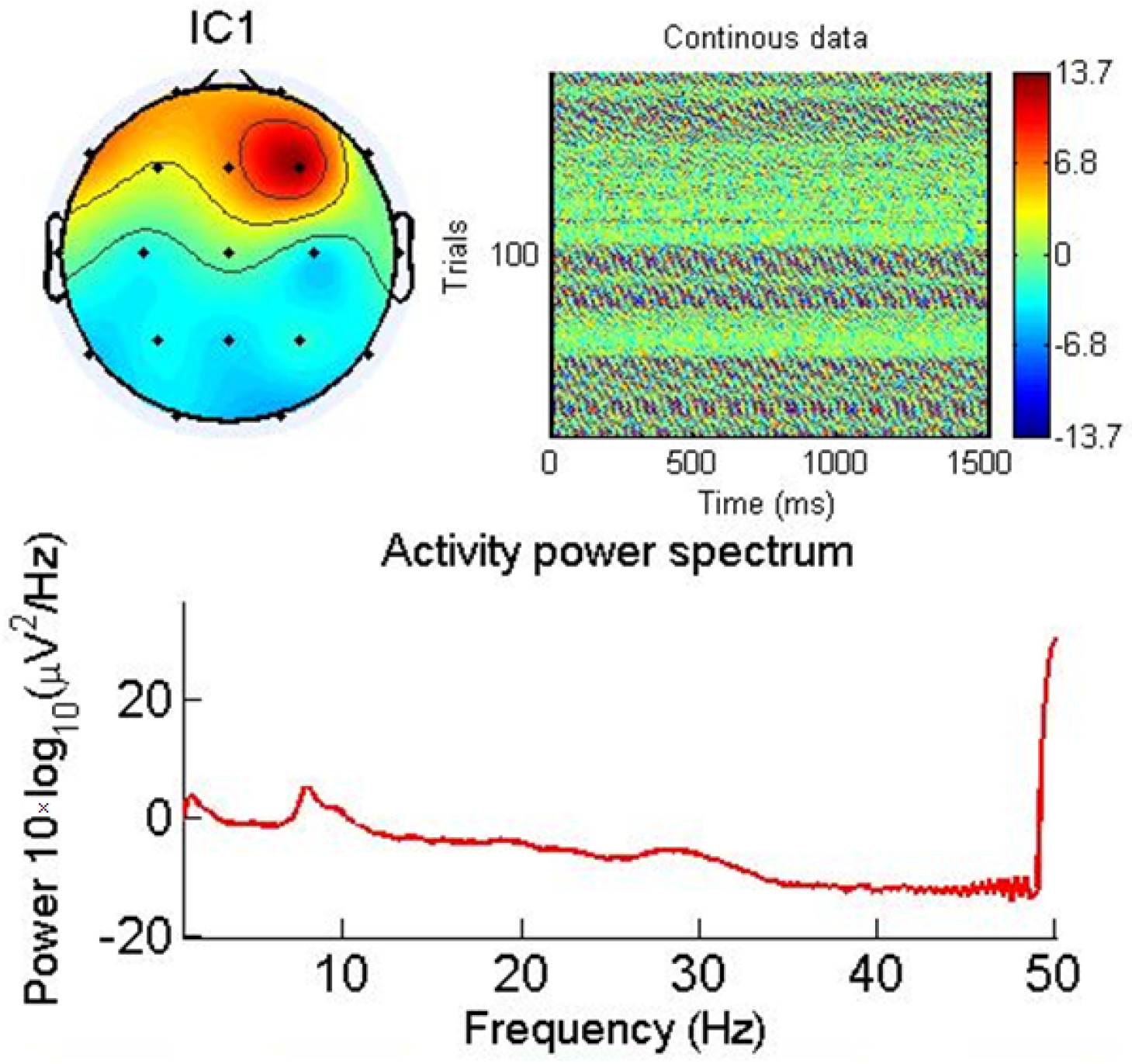

3.3. Real-World Patient Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arabi, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Akhavanallaf, M.; Arab, A.; Zaidi, S.; Ghaffarian, A. Comparative study of algorithms for synthetic CT generation from MRI: Consequences for MRI-guided radiation planning in the pelvic region. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 5218–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Ma, X. Brain MRI super resolution using 3D deep densely connected neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Peng, Y.; Dai, G.; Lu, B.; Kong, W. Coupled Projection Transfer Metric Learning for Cross-Session Emotion Recognition from EEG. Systems 2022, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuet, L.; Ishii, R.; Pascual-Marqui, R.D.; Iwase, M.; Kurimoto, R.; Aoki, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Takahashi, H.; Nakahachi, T.; Takeda, M. Resting-state EEG source localization and functional connectivity in schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, B.; Prichep, L.; Mosconi, L.; John, E.R.; Glodzik-Sobanska, L.; Boksay, I.; Monteiro, I.; Torossian, C.; Vedvyas, A.; Ashraf, N.; et al. The pre–mild cognitive impairment, subjective cognitive impairment stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2008, 4, S98–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chung, F.; Wang, S. Recognition of multiclass epileptic EEG signals based on knowledge and label space inductive transfer. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiadis, C.; Halliday, D.M.; Kazis, D.; Klados, M.A. Functional connectivity of interictal iEEG and the connectivity of high-frequency components in epilepsy. Brain Organoid Syst. Neurosci. J. 2023, 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, W.; Li, Y.; Wen, P.; Miften, F.S.; Oudah, A.Y.; Ghayab, H.R.A. Extracting epileptic features in EEGs using a dual-tree complex wavelet transform coupled with a classification algorithm. Brain Res. 2022, 1779, 147777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasmanoglou, A.; Giannakakis, G.; Vorgia, P.; Antonakakis, M.; Zervakis, M. Semi-Supervised anomaly detection for the prediction and detection of pediatric focal epileptic seizures on fused EEG and ECG data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 101, 107083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Aziz, S. Simple detection of epilepsy from EEG signal using local binary pattern transition histogram. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 150252–150267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugabah, A.; Abouhawwash, M.; Alsaade, A. Brain epilepsy seizure detection using bio-inspired krill herd and artificial alga optimized neural network approaches. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 3317–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, A.I.; El-Soud, M.A.; El-Henawy, I.M. An automated approach for epilepsy detection based on tunable Q-wavelet and firefly feature selection algorithm. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2018, 2018, 5812872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidvar, M.; Zahedi, A.; Bakhshi, H. EEG signal processing for epilepsy seizure detection using 5-level Db4 discrete wavelet transform, GA-based feature selection and ANN/SVM classifiers. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 10395–10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukriti; Chakraborty, M.; Mitra, D. Epilepsy seizure detection using kurtosis based VMD’s parameters selection and bandwidth features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 64, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamoulis, C.; Chang, J.; Johnson, R. Noninvasive seizure localization with single-photon emission computed tomography is impacted by preictal/early ictal network dynamics. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M.M.N.; Rahman, A.H.M.; Ali, M.A. Hybrid EEG–eye tracker: Automatic identification and removal of eye movement and blink artifacts from electroencephalographic signal. Sensors 2016, 16, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedurkar, D.P.; Metkar, S.P. Multiresolution approach for artifacts removal and localization of seizure onset zone in epileptic EEG signal. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 57, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshava, M.G.N.; Ahmed, K.Z. Correction of ocular artifacts in EEG signal using empirical mode decomposition and cross-correlation. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 9, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, T.; Yoshida, N.; Tanaka, T. Automated detection of abnormalities from an EEG recording of epilepsy patients with a compact convolutional neural network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 70, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafadideh, A.T.; Asl, B.M. A new data covariance matrix estimation for improving minimum variance brain source localization. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 143, 105324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, R.; Kanaga, E.G. Theoretical and methodological analysis of EEG based seizure detection and prediction: An exhaustive review. J. Neurosci. Methods 2022, 369, 109483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. A new localization method for epileptic seizure onset zones based on time-frequency and clustering analysis. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 111, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierlo, P.V.; Carrette, S.; Vonck, K. Ictal EEG source localization in focal epilepsy: Review and future perspectives. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 2600–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staljanssens, W.; Carrette, B.; Meurs, A. Seizure onset zone localization from ictal high-density EEG in refractory focal epilepsy. Brain Topogr. 2016, 30, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T. Integrating optimized multiscale entropy model with machine learning for the localization of epileptogenic hemisphere in temporal lobe epilepsy using resting-state fMRI. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1834123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakiri, A.; Panagiotopoulos, S.; Tzallas, D. Mapping brain networks and cognitive functioning after stroke: A systematic review. Brain Organoid Syst. Neurosci. J. 2024, 2, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, D.; Amini, A.; Friedman, D.; Doyle, W.; Pacia, S.; Kuzniecky, R. Validation of an EEG seizure detection paradigm optimized for clinical use in a chronically implanted subcutaneous device. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 358, 109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Guo, K.; Lu, K.; Meng, K.; Lu, J.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Yu, R.; Zhang, R. Localizing the seizure onset zone and predicting the surgery outcomes in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: A new approach based on the causal network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 258, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, M.; Yang, S.; Xian, X.; Fotedar, N.; Liu, F. Multi-Modal Electrophysiological Source Imaging With Attention Neural Networks Based on Deep Fusion of EEG and MEG. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmirriahi, M.; Rabbani, H. A review of EEG-based localization of epileptic seizure foci: Common points with multimodal fusion of brain data. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, S.M.; Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Shams, M.; Seraji, M.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Localization of epileptic foci based on simultaneous EEG–fMRI data. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 645594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağmur, F.D.; Sertbaş, A. A High-Performance Method Based on Features Fusion of EEG Brain Signal and MRI-Imaging Data for Epilepsy Classification. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2024, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Rouzbahani, H.; Vogrin, S.; Cao, M.; Plummer, C.; McGonigal, A. Multimodal and quantitative analysis of the epileptogenic zone network in the pre-surgical evaluation of drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2024, 54, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsich, J.; Iannotti, G.R.; Ridley, B.; Shamshiri, E.A.; Sheybani, L.; Grouiller, F.; Bartolomei, F.; Seeck, M.; Lazeyras, F.; Ranjeva, J.P.; et al. Altered correlation of concurrently recorded EEG-fMRI connectomes in temporal lobe epilepsy. Netw. Neurosci. 2024, 8, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekmati, R.; Azencott, R.; Zhang, W.; Chu, Z.D.; Paldino, M.J. Localization of epileptic seizure focus by computerized analysis of fMRI recordings. Brain Inform. 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Pang, Z.; Wang, Z. Epileptic seizure prediction by a system of particle filter associated with a neural network. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2009, 2009, 638534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Siuly; Zhang, Y. Epileptic seizure detection from EEG signals using logistic model trees. Brain Inform. 2016, 3, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunekar, P.; Gupta, M.K.; Gaur, P. Detection of epileptic seizure in EEG signals using machine learning and deep learning techniques. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 71, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kode, H.; Elleithy, K.; Almazaydeh, L. Epileptic seizure detection in EEG signals using machine learning and deep learning techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 80657–80668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zheng, W.; Feng, Y.; Li, X. LMA-EEGNet: A Lightweight Multi-Attention Network for Neonatal Seizure Detection Using EEG signals. Electronics 2024, 13, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouichka, O.; Echtioui, A.; Hamam, H. Deep Learning Models for Predicting Epileptic Seizures Using iEEG Signals. Electronics 2022, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, J. A Robust Automatic Epilepsy Seizure Detection Algorithm Based on Interpretable Features and Machine Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, S.M.; Alizadeh, M.; Mazloum, J.; Baleghi, Y. Modified binary salp swarm algorithm in EEG signal classification for epilepsy seizure detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 78, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, S.M.; Subasi, A. Effective epileptic seizure detection based on the event-driven processing and machine learning for mobile healthcare. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 13, 3619–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, A.; Kevric, J.; Canbaz, M.A. Epileptic seizure detection using hybrid machine learning methods. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, J.T.; Rosa, J.L.G. Binary and multiclass classifiers based on multitaper spectral features for epilepsy detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 66, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Oh, S.L.; Hagiwara, Y.; Tan, J.H.; Adeli, H. Deep convolutional neural network for the automated detection and diagnosis of seizure using EEG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 100, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Rivero, D.; Dorado, J.; Rabuñal, J.R.; Pazos, A. Automatic epileptic seizure detection in EEGs based on line length feature and artificial neural networks. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 191, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, D.E.; Callan, A.M.; Kroos, C.; Vatikiotis-Bateson, E. Multimodal contribution to speech perception revealed by independent component analysis: A single-sweep EEG case study. Cogn. Brain Res. 2001, 10, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Shams, M.; Fayaz, F.; Rajabion, L.; Mirbagheri, M.; Araabi, B.N.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Quantitative determination of concordance in localizing epileptic focus by component-based EEG-fMRI. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 177, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Chen, J.E. Multimodal EEG-fMRI: Advancing insight into large-scale human brain dynamics. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 18, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, R.N.; Abdulrahman, H.; Flandin, G.; Litvak, V. Multimodal integration of M/EEG and f/MRI data in SPM12. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N.E.; Tolba, A.S.; Rashad, M.Z.; Belal, T.; Sarhan, S. Multimodal analysis of electroencephalographic and electrooculographic signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 137, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradsen, I.; Beniczky, S.; Wolf, P.; Kjaer, T.W.; Sams, T.; Sorensen, H.B. Automatic multi-modal intelligent seizure acquisition (MISA) system for detection of motor seizures from electromyographic data and motion data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2012, 107, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.M.; Lee, H.M.; Lim, J.H.; Seo, J. A Negative Emotion Recognition System with Internet of Things-Based Multimodal Biosignal Data. Electronics 2023, 12, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Nejad, Y.; Beheshti, S. Efficient high resolution sLORETA in brain source localization. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 016013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Adali, T.; Yu, Q.; Chen, J.; Calhoun, V.D. A review of multivariate methods for multimodal fusion of brain imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 204, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaho, S.; Kiuchi, Y.; Umeyama, S. MICA: Multimodal independent component analysis. In Proceedings of the IJCNN’99: International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Washington, DC, USA, 10–16 July 1999; Proceedings (Cat. No.99CH36339). Volume 2, pp. 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.; Sedghizadeh, S. Number of source signal estimation by the mean squared eigenvalue error. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 66, 5694–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Song, Z. Online monitoring of nonlinear multiple mode processes based on adaptive local model approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2008, 16, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghsh, E.; Danesh, M.; Beheshti, S. Unified left eigenvector (ULEV) for blind source separation. Electron. Lett. 2022, 58, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.; Shamsi, M. ϵ-confidence approximately correct (ϵ-coac) learnability and hyperparameter selection in linear regression modeling. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 14273–14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.; Beheshti, S. Relative entropy (RE)-based LTI system modeling equipped with simultaneous time delay estimation and online modeling. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 113885–113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.; Nidoy, E.; Rahman, F. K-mace and kernel k-mace clustering. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 17390–17403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.; Bommanahally, V. Minimum Mismatch Modeling (3M) Hyperparameter Selection in Autoregressive Moving Average (ARMA) Modeling. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 133681–133693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, K.; Umapathy, K.; Beheshti, S. Reliable truncation parameter selection and model order estimation for stochastic subspace identification. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 362, 107766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Basu, A. Medical Image Denosing via Explainable AI Feature Preserving Loss. In Proceedings of the Smart Multimedia, Paris, France, 19–21 December 2025; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

| Number of | MSEE+ | MSEE+ | MSEE+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Bases | PCA+ICA | PCA+MICA | ULeV |

| 1 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.97 |

| 3 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| SNR Difference | MSEE+ | MSEE+ | MSEE+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| (dB) | PCA+ICA | PCA+MICA | ULeV |

| 0 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.98 |

| 5 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.97 |

| 10 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.93 |

| 15 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.88 |

| # | MSEE | MSEE | MSEE | MieSoL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHR-sLORETA | +PCA+ICA | +PCA+MICA | ULeV | ||

| +EHR-sLORETA | +EHR-sLORETA | +sLORETA | |||

| 1 | (7, 6.32) | (7, 5.30) | (10, 3.34) | (9, 2.08) | (10, 1.22) |

| 2 | (7, 7.68) | (7, 5.88) | (11, 4.29) | (9, 2.42) | (10, 1.44) |

| 3 | (4, 9.42) | (3, 8.62) | (13, 6.12) | (11, 3.65) | (10, 2.23) |

| 4 | (9, 7.12) | (7, 5.52) | (10, 4.03) | (9, 2.19) | (10, 1.21) |

| 5 | (8, 8.24) | (6, 6.07) | (11, 4.54) | (9, 2.72 | (10, 1.80) |

| 6 | (6, 10.14) | (3, 8.14) | (12, 5.67) | (11, 3.34) | (10, 2.26) |

| 7 | (8, 7.02) | (7, 5.16) | (10, 3.61) | (10, 1.89) | (10, 1.01) |

| 8 | (7, 11.23) | (5, 7.97) | (12, 5.44) | (11, 3.55) | (10, 2.10) |

| 9 | (8, 7.78) | (7, 5.26) | (13, 6.62) | (10, 1.99) | (10, 1.22) |

| 10 | (8, 8.09) | (7, 5.93) | (11, 4.26) | (9, 2.55) | (10, 1.25) |

| 11 | (7, 7.23) | (6, 6.06) | (11, 4.48) | (9, 2.67) | (10, 1.22) |

| 12 | (5, 10.76) | (3, 8.45) | (10, 5.93) | (11, 3.28) | (10, 2.03) |

| # | MSEE | MSEE | MSEE | MieSoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +PCA+ICA | +PCA+MICA | ULeV | ||

| +EHR-sLORETA | +EHR-sLORETA | +sLORETA | ||

| 1 | (1, 5.65) | (3, 4.02) | (3, 2.23) | (2, 1.45) |

| 2 | (2, 6.61) | (3, 4.53) | (2, 2.75) | (2, 1.82) |

| 3 | (2, 8.74) | (4, 6.45) | (2, 3.98) | (1, 2.49) |

| 4 | (3, 5.85) | (3, 4.26) | (4, 2.42) | (2, 1.70) |

| 5 | (1, 6.40) | (3, 4.87) | (2, 3.05) | (1, 1.09) |

| 6 | (1, 8.47) | (4, 6.33) | (2, 3.63) | (2, 2.68) |

| 7 | (2, 5.35) | (2, 3.94) | (3, 2.21) | (3, 1.27) |

| 8 | (4, 8.30) | (4, 5.68) | (3, 3.50) | (3, 2.33) |

| 9 | (1, 5.59) | (3, 4.48) | (4, 2.32) | (3, 1.45) |

| 10 | (4, 6.26) | (4, 4.59) | (4, 2.92) | (3, 1.98) |

| 11 | (2, 6.39) | (4, 4.81) | (2, 3.03) | (2, 2.05) |

| 12 | (3, 8.78) | (3, 6.24) | (2, 3.61) | (1, 2.97) |

| 13 | (3, 5.57) | (5, 3.95) | (4, 2.27) | (2, 1.42) |

| 14 | (1, 6.15) | (3, 4.51) | (3, 2.70) | (1, 1.83) |

| 15 | (1, 8.43) | (2, 5.89) | (3, 3.24) | (1, 2.52) |

| 16 | (1, 6.19) | (3, 4.61) | (3, 2.82) | (1, 1.89) |

| 17 | (2, 8.44) | (2, 5.58) | (4, 3.04) | (2, 1.85) |

| 18 | (1, 8.15) | (2, 5.62) | (4, 3.39) | (3, 2.37) |

| 19 | (4, 5.49) | (2, 3.81) | (4, 2.16) | (3, 1.41) |

| 20 | (2, 7.86) | (3, 5.38) | (4, 3.10) | (2, 2.03) |

| 21 | (3, 5.82) | (4, 3.65) | (3, 1.93) | (3, 1.08) |

| 22 | (3, 5.36) | (3, 3.88) | (3, 2.01) | (3, 1.27) |

| 23 | (2, 5.61) | (4, 4.12) | (2, 2.43) | (3, 1.35) |

| 24 | (1, 6.11) | (5, 4.67) | (3, 2.99) | (2, 1.72) |

| 25 | (3, 7.56) | (5, 5.47) | (4, 3.20) | (2, 1.98) |

| 26 | (1, 8.56) | (3, 5.84) | (4, 3.23) | (3, 1.82) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beheshti, S.; Naghsh, E.; Sadat-Nejad, Y.; Naderahmadian, Y. Multimodal Mutual Information Extraction and Source Detection with Application in Focal Seizure Localization. Electronics 2025, 14, 4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244897

Beheshti S, Naghsh E, Sadat-Nejad Y, Naderahmadian Y. Multimodal Mutual Information Extraction and Source Detection with Application in Focal Seizure Localization. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244897

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeheshti, Soosan, Erfan Naghsh, Younes Sadat-Nejad, and Yashar Naderahmadian. 2025. "Multimodal Mutual Information Extraction and Source Detection with Application in Focal Seizure Localization" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244897

APA StyleBeheshti, S., Naghsh, E., Sadat-Nejad, Y., & Naderahmadian, Y. (2025). Multimodal Mutual Information Extraction and Source Detection with Application in Focal Seizure Localization. Electronics, 14(24), 4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244897