1. Introduction

With the rapid development of music streaming services, the global music industry is undergoing unprecedented digital transformation. According to the IFPI Global Music Report 2025, global paid subscription streaming accounts reached 752 million in 2024, with music catalog sizes reaching tens of millions of tracks [

1]. In this massive digital ecosystem, efficiently identifying key music relationship patterns is vital for improving user experience, supporting personalized recommendations, and understanding music evolution trends.

Traditional music analysis methods rely heavily on content-based feature extraction, collaborative filtering, or simple metadata matching [

2]. While these approaches have proven useful over the past decades, they face increasing challenges given the complexity and heterogeneity of modern music data. Music data contains rich semantic information spanning multiple modalities: audio features, lyrical content, artist relationships, genre classifications, emotion labels, and cross-domain musical connections. Simple frequency-based metrics fail to capture the intricate structural relationships and semantic dependencies that characterize contemporary music networks [

3].

The Music Knowledge Graph (MKG) represents a paradigm shift in organizing and analyzing musical knowledge. By integrating multi-type entities such as songs, artists, albums, genres, and emotion labels along with their semantic relationships, MKGs provide powerful infrastructure for music relationship identification and trend forecasting [

4]. However, identifying key music relationship nodes within an MKG remains a significant challenge due to several factors: the massive scale of music data (often millions of entities), the heterogeneous nature of entity types with fundamentally different semantic meanings, the dynamic evolution of musical domains, and the need for interpretable results that can guide recommendation decisions.

This task can be formalized as a node importance estimation problem—a core challenge in graph mining with broad applications in social network analysis, recommendation systems, resource allocation, and knowledge discovery. Traditional node importance estimation methods emphasize centrality measures such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality [

5], and PageRank [

6]. However, these methods exhibit obvious limitations when dealing with heterogeneous graphs: they treat all node types equally, ignore semantic differences between entity types, and often fail to capture the structural importance of nodes in maintaining network connectivity and information flow.

In recent years, graph robustness-based methods have emerged as a promising approach to assess a node’s impact on network stability [

7,

8]. Graph robustness metrics measure how the removal of a node affects the overall connectivity and efficiency of the network, providing a structure-aware evaluation of node importance. However, the exact computation of graph robustness has complexity up to

, which is computationally infeasible for large-scale MKGs [

9]. Even approximate methods typically require

or higher complexity, limiting their practical applicability for real-time analysis and dynamic graphs.

The emergence of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) has revolutionized graph-structured data analysis, achieving remarkable success in tasks such as node classification, link prediction, and graph generation [

10,

11,

12]. GNNs learn node representations by iteratively aggregating information from neighboring nodes, enabling them to capture both local structural patterns and global graph properties. Recent advances in neural network acceleration and optimization [

13] have further enabled efficient deployment of deep learning models on resource-constrained platforms, demonstrating the broader trend toward practical, scalable machine learning systems. Several recent works have proposed GNN-based methods for node importance estimation [

14,

15]. However, these methods often overlook the heterogeneous nature of MKGs, in which different entity types (songs, relationships, artists, albums) have fundamentally different semantic meanings and structural roles.

In MKGs, music relationship nodes face severe class imbalance—they are vastly outnumbered by song nodes, often by a ratio of 1:20 or more. This extreme imbalance creates several challenges for existing GNN methods. First, standard message-passing mechanisms treat all nodes equally during information aggregation, leading to inefficient computation, with most resources spent on less informative song nodes. Second, uniform propagation depth across all nodes can cause over-smoothing [

16], where the representations of different nodes become increasingly similar as the network depth increases, reducing the discriminative power needed to identify critical relationship nodes. Third, fixed activation functions such as ReLU and GELU fail to capture the structural and semantic heterogeneity across different node types and local graph patterns, limiting the model’s ability to adapt to the diverse characteristics of MKG entities.

To address these fundamental challenges, this paper proposes MUSIGAIN, a GATv2-based adaptive framework that synergistically combines graph robustness metrics with advanced graph neural network mechanisms. MUSIGAIN introduces three key innovations that work together to enable efficient and accurate node importance estimation in heterogeneous MKGs:

Dynamic Propagation Control. We introduce a layer-wise dynamic skipping mechanism that monitors the third-order embedding difference of each node to detect convergence. Nodes whose representations have stabilized skip further updates, adaptively controlling propagation depth on a per-node basis. This mechanism simultaneously addresses over-smoothing in deep architectures and reduces computational overhead by 30–40%, enabling efficient processing of large-scale graphs.

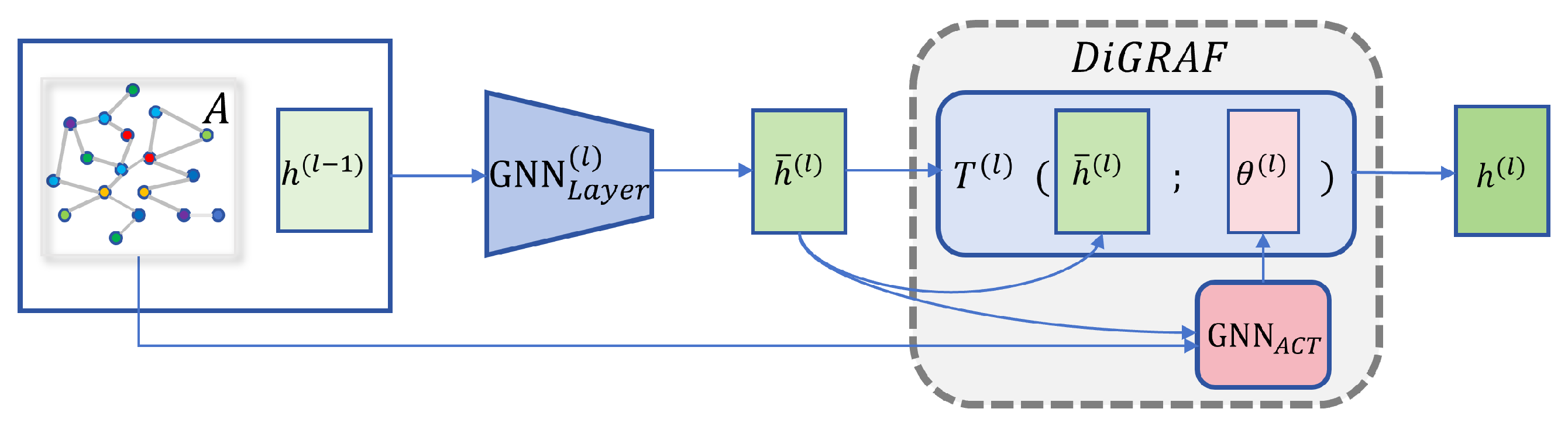

Semantic-Adaptive Nonlinearity. We incorporate the DiGRAF (Diffeomorphic Graph-Adaptive Activation Function) [

17] that learns node-specific activation parameters based on node type, current embedding, and local structural features. Unlike fixed activation functions that apply uniform transformations, DiGRAF enables each node to have a customized nonlinear mapping that reflects its semantic role and structural context, better capturing the heterogeneity inherent in MKGs.

Robustness-Supervised Ranking. Rather than predicting absolute robustness values (which requires expensive eigenvalue computations), we employ ranking-based optimization that focuses on learning the correct relative ordering of node importance. By combining pairwise ranking loss with listwise softmax loss, the model learns to identify structurally critical nodes while avoiding the computational bottleneck of exact robustness calculation.

These innovations are integrated into a unified architecture featuring a Location-Sensing Transformer (LST) for type-specific feature extraction, GATv2-based message passing with attention mechanisms, and a fusion layer that combines spatial and temporal information patterns.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We propose MUSIGAIN, a GATv2-based adaptive framework that combines layer-wise dynamic skipping and DiGRAF adaptive activation to enhance both representation capability and computational efficiency in heterogeneous music knowledge graphs. The dynamic skipping mechanism monitors embedding stability to prevent over-smoothing while reducing computation by 30–40%. Additionally, DiGRAF provides node-specific transformations to capture semantic heterogeneity across entity types.

We introduce a ranking-based optimization approach, supervised by graph-robustness metrics, that focuses on relative importance ordering rather than absolute value prediction. This approach efficiently identifies critical music relationship nodes and contributes to discovering music trends while maintaining computational efficiency.

We conduct extensive experiments on four real-world music knowledge graphs across different musical genres (pop, rock, jazz, and classical), showing that MUSIGAIN consistently outperforms strong baselines. The framework achieves a maximum of 96.78% accuracy in Top-5% node identification, with improvements reaching 3.91 percentage points over GATv2, and exhibits favorable scalability for industrial deployment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on music knowledge graphs, node importance estimation, and graph neural networks.

Section 3 provides the problem definition, including the formal specification of music knowledge graphs and graph robustness metrics.

Section 4 details the MUSIGAIN framework architecture.

Section 5 presents the experimental setup, and

Section 6 analyzes the results.

Section 7 discusses key findings and future directions. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Music Knowledge Graphs and Multi-Relationship Mining

Music knowledge graphs have emerged as powerful tools for organizing and analyzing musical innovation [

3]. Oramas et al. [

3] pioneered the use of knowledge graph technology to generate music recommendation systems, demonstrating the potential of structured knowledge representation for music mining. Unlike traditional music analysis methods that focus primarily on collaborative filtering networks or simple audio feature matching, MKGs integrate multiple entity types and relationship categories to capture the rich semantic structure of musical domains.

Recent advances in music knowledge graph construction have leveraged sophisticated natural language processing and audio analysis techniques. Silva et al. [

18] proposed heterogeneous graph neural networks for music emotion recognition, modeling the intrinsically multimodal nature of musical data by integrating information from audio and lyrics. Ding et al. [

19] introduced knowledge-embedded music representations for genre classification, demonstrating how external knowledge can enrich audio-based features. Recent work by Li et al. [

20] further advances music genre classification using channel-aware convolutional neural networks with adaptive attention mechanisms, achieving state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets. Zhang et al. [

21] developed hybrid recommendation algorithms that combine music genes with knowledge graph embeddings, showing improved performance over single-modal approaches. Wang et al. [

22] extend this line of work by proposing hybrid music recommendation systems that leverage graph neural networks to capture complex user-item-context interactions. The Million Song Dataset [

23] has become a cornerstone resource for large-scale music analysis, providing standardized benchmarks for evaluating recommendation algorithms. Recent advances in music emotion recognition [

24] and music analysis with GNNs [

25] demonstrate the growing importance of deep learning approaches for understanding musical content and structure.

The construction of MKGs typically involves several key steps: entity extraction from music databases, relationship identification between entities, knowledge fusion across multiple data sources, and quality validation. Modern approaches leverage natural language processing techniques to extract structured information from unstructured music texts such as lyrics and reviews. However, once constructed, the challenge shifts to identifying which music relationships within the MKG are most influential or represent emerging music trends.

Music relationship identification in MKGs differs fundamentally from traditional document clustering or topic modeling approaches. In MKGs, music relationships are explicit entities connected through multiple relationship types to songs, artists, albums, and genres [

26]. The importance of a relationship is determined not just by the number of associated songs, but by its structural position in the knowledge graph, its connections to influential artists and albums, and its role in bridging different musical domains. This structural perspective on relationship importance motivates the use of graph-based methods rather than purely content-based approaches.

2.2. Node Importance Estimation

Node importance estimation is a fundamental problem in graph mining with broad applications across multiple domains [

27]. Traditional approaches are based on various centrality measures that quantify a node’s structural significance. Degree centrality counts the number of connections a node has, betweenness centrality measures how often a node appears on shortest paths between other nodes, and PageRank [

6] evaluates importance through a random walk model where importance is propagated through graph edges. Additional classical metrics include eigenvector centrality [

28] and Katz centrality [

29], which consider the importance of neighboring nodes in determining a node’s significance.

While these classical centrality measures have proven useful in many applications, they suffer from significant limitations when applied to heterogeneous graphs like MKGs. First, they treat all edges equally, ignoring the semantic differences between relationship types. For instance, a “performer” relationship between a song and an artist has a fundamentally different meaning than a “similar to” relationship between two songs, yet degree centrality would count them equally. Second, these measures assign uniform importance to all node types, failing to account for the fact that music relationship nodes and song nodes play fundamentally different roles in the knowledge graph.

Graph robustness-based methods offer an alternative perspective on node importance. Rather than measuring structural position, these approaches evaluate how a node’s removal affects the overall connectivity and efficiency of the network. Common graph robustness metrics include connectivity-based indicators, such as the size of the largest connected component; distance-based indicators, such as network efficiency and average path length; and spectrum-based indicators, such as algebraic connectivity and Laplacian energy.

Among robustness metrics, spectral methods have received particular attention due to their solid theoretical foundations [

30]. The weighted spectrum, defined as the sum of all eigenvalues of the graph Laplacian matrix [

31], reflects the overall network connectivity and information propagation capability. When a node is removed from the graph, the change in weighted spectrum provides a quantitative measure of that node’s structural importance. However, exact computation of spectral robustness metrics requires eigenvalue decomposition, which has

complexity for a single calculation and must be repeated for each node, resulting in overall complexity up to

for complete node importance ranking.

Recent advances in node importance estimation have explored machine learning approaches. Lü et al. [

32] provide a comprehensive review of vital node identification methods, categorizing approaches by their theoretical foundations and computational complexity. Wang et al. [

33] present a comprehensive survey of critical node identification techniques in complex networks, systematically categorizing methods and highlighting challenges in dynamic and higher-order networks. Fan et al. [

34] propose using deep reinforcement learning to identify key players in complex networks, demonstrating that learned approaches can outperform traditional centrality measures in certain contexts. Recent work on GNN-based ranking [

35] shows that learning to rank actions in graph-structured problems can achieve better generalization than value-based approaches.

Despite the effectiveness of these classical approaches in quantifying node significance, they primarily rely on static structural heuristics and often fail to scale or adapt to heterogeneous knowledge graphs with diverse semantic relations. This limitation has motivated the development of graph neural network (GNN) based methods, which leverage representation learning to capture higher-order dependencies and complex interactions among nodes.

2.3. Graph Neural Networks for Node Importance Estimation

The advent of Graph Neural Networks has opened new possibilities for scalable node importance estimation. GNNs learn distributed representations of nodes by iteratively aggregating and transforming features from neighboring nodes [

36]. Early GNN architectures include Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), which extend the convolution operation from regular grids to irregular graph structures, and GraphSAGE [

11], which introduces an inductive learning framework that can generalize to unseen nodes through neighborhood sampling.

Graph attention mechanisms have further enhanced GNN expressiveness by allowing nodes to assign different weights to different neighbors [

37]. The original Graph Attention Networks (GAT) enable adaptive neighbor weighting through learned attention coefficients. However, Brody et al. [

12] identified limitations in the original GAT attention mechanism and proposed GATv2, which achieves truly dynamic attention by adjusting the order of operations in attention score computation. Recent applications of GATv2 [

38] demonstrate its effectiveness in solving complex combinatorial problems through graph-based deep learning, validating the importance of dynamic attention mechanisms.

Several recent works have proposed GNN-based methods for estimating node importance in knowledge graphs. GENI [

14] integrates structural features with external signals such as text content to estimate node importance in knowledge graphs. MULTIIMPORT [

15] extends this approach by inferring node importance from multiple input signals, including graph structure, node features, and temporal dynamics. These methods achieve good performance on knowledge graphs with relatively balanced entity type distributions. However, they do not fully exploit robustness metrics and typically treat all nodes equally during message passing, which can lead to inefficiency when applied to highly imbalanced graphs like MKGs.

A fundamental challenge for GNN-based importance estimation in MKGs is the over-smoothing problem [

16]. As GNNs stack more layers to capture long-range dependencies, node representations tend to become increasingly similar, reducing the discriminative power needed for fine-grained importance ranking. Rusch et al. [

39] provide a comprehensive survey on over-smoothing in GNNs, axiomatically defining it as the exponential convergence of node features and extending the analysis to continuous-time GNNs. Li et al. [

40] provide theoretical insights into this phenomenon, showing that repeated averaging operations in deep GNNs lead to convergence to a stationary distribution. Various solutions have been proposed, including DropEdge [

41], which randomly drops edges during training, PairNorm [

42], which normalizes node features to maintain diversity, and recent novel dropout approaches [

43], which specifically target over-smoothing mitigation. Zhang et al. [

44] propose channel-attentive graph neural networks that learn adaptive channel-wise message passing to alleviate over-smoothing and achieve state-of-the-art performance on heterophilous graphs.

2.4. Adaptive Mechanisms in Graph Neural Networks

Recent advances in GNN architectures have introduced various adaptive mechanisms to address the limitations of standard message passing. Residual connections and skip connections allow information to bypass intermediate layers, helping to preserve input features and mitigate over-smoothing. Adaptive depth mechanisms dynamically determine the number of layers to apply to each node based on local graph structure or task requirements. For instance, nodes in dense communities might require fewer layers to capture their local structure, while nodes bridging different communities might benefit from deeper propagation.

Heterogeneous graph neural networks explicitly model different node and edge types through type-specific parameters [

45]. Schlichtkrull et al. [

46] propose relational graph convolutional networks (R-GCN) that use relation-specific weight matrices to handle multi-relational data. Recent advances in heterogeneous GNNs [

47] introduce adaptive relation attention mechanisms for improved node classification, demonstrating the importance of learning type-specific attention weights. These methods use relation-specific transformations and attention mechanisms to capture semantic differences between entity types.

Recent work in music-specific GNN applications has shown promising results. Mao et al. [

48] propose multistage graph embeddings for music recommendation, demonstrating improved cold-start performance. Korzeniowski et al. [

49] use GNNs for artist similarity computation, showing that learned representations outperform traditional collaborative filtering approaches. Ferraro et al. [

50] combine audio and text features in a hybrid recommender system for automatic playlist continuation. Recent advances [

51] leverage artificial intelligence and knowledge graphs for online music learning platforms, demonstrating the broader applicability of graph-based approaches in music education and analysis. Silva et al. [

52] propose parallel convolutional neural networks for music genre classification, achieving improved accuracy through multi-scale feature extraction.

The DiGRAF (Diffeomorphic Graph-Adaptive Activation Function) [

17] represents a significant advance in adaptive nonlinearity for GNNs. Unlike fixed activation functions, DiGRAF parameterizes the activation function itself and learns these parameters based on node features, node types, and local structural information. This approach enables the network to apply different nonlinear transformations to different nodes, potentially capturing the heterogeneous nature of complex graphs more effectively. Recent work on adaptive activation functions [

53] further demonstrates the benefits of morphing activation functions that can dynamically adjust their shape based on input characteristics, providing additional flexibility for neural network architectures.

Beyond traditional supervised learning, recent multimodal graph transformers [

54] have demonstrated the ability to integrate diverse data modalities (text, images, audio) within graph structures, showing promise for complex knowledge graphs. Self-supervised graph learning [

55,

56] has emerged as a powerful paradigm that learns representations without explicit labels through contrastive learning and graph augmentation strategies. While these approaches offer exciting possibilities for reducing annotation requirements and improving generalization, they have primarily been applied to homogeneous graphs or simple heterogeneous structures. MUSIGAIN differs in that it focuses on node importance estimation in highly heterogeneous music knowledge graphs with explicit robustness-based supervision, addressing a complementary but distinct challenge. Future work could explore integrating self-supervised pretraining with our ranking-based framework to further enhance performance and reduce dependency on labeled robustness scores.

3. Problem Definition

3.1. Music Knowledge Graph

A music knowledge graph can be formally defined as a heterogeneous graph , where V is the set of nodes representing various entities in the music domain, including songs, artists, albums, genres, emotion labels, and music relationships; is the set of edges representing relationships between entities; is the node type mapping function, where is the set of node types; and is the edge type mapping function, where is the set of edge types.

In MKGs, typically includes Song, Artist, Album, Genre, Emotion, and MusicRelation, while common edge types include PerformedBy, BelongsToAlbum, HasGenre, HasEmotion, SimilarTo, and Collaborates. For example, a song “Bohemian Rhapsody” might be connected to the artist “Queen” through a PerformedBy edge, to the album “A Night at the Opera” through a BelongsToAlbum edge, to the genre “Progressive Rock” through a HasGenre edge, and to other songs through SimilarTo edges based on acoustic or semantic similarity.

The heterogeneous nature of MKGs distinguishes them from traditional homogeneous graphs [

27]. Different node types have distinct semantic meanings and play different roles in representing musical knowledge. For instance, song nodes represent specific musical works with concrete audio features and lyrics, relationship nodes represent general musical concepts or patterns that connect multiple songs, and artist nodes represent individuals or groups who create music. This heterogeneity must be explicitly modeled [

26] to accurately capture node importance.

3.2. Node Importance Estimation Task

Given a music knowledge graph and a target node type set (typically for music relationship mining), the goal of node importance estimation is to learn a scoring function such that for any two nodes where , if is structurally more important than , then .

The key challenge is to define and compute structural importance in a way that: (1) captures the multifaceted nature of importance in heterogeneous graphs, where a node’s importance depends not just on its connections but also on its type and the types of its neighbors; (2) scales efficiently to large graphs with hundreds of thousands of nodes, requiring computational complexity that is practical for real-world applications; (3) provides interpretable results that align with domain expertise, so that music professionals can understand and trust the rankings; and (4) generalizes to unseen nodes in an inductive setting [

11], allowing the model to evaluate new songs and relationships as they are added to the knowledge graph.

3.3. Graph Robustness Metrics

Graph robustness measures the network’s ability to maintain functionality when facing perturbations or targeted attacks. Intuitively, a network is considered robust if it can maintain connectivity and efficient information flow despite the removal of nodes or edges. This property is of particular importance in music knowledge graphs (MKGs), where the removal of critical relationship nodes may significantly affect the connectivity between songs, artists, and genres.

We adopt the weighted spectrum as our primary robustness metric, which is defined as the sum of all eigenvalues of the normalized graph Laplacian matrix:

where

is the

i-th eigenvalue of the normalized Laplacian matrix

, with

A being the adjacency matrix and

D being the degree matrix. This metric reflects the overall connectivity and diffusion capacity of the graph.

When a node

v is removed from the graph, we can measure its importance by the change in weighted spectrum:

where

denotes the graph with node

v and all its incident edges removed. Nodes with larger

values are more structurally critical, as their removal causes greater degradation in network connectivity and information flow capability.

Beyond the weighted spectrum, robustness can also be analyzed through connectivity and efficiency metrics. One common indicator is

network efficiency, which evaluates the average inverse shortest-path distance across all node pairs:

where

is the shortest path length between nodes

i and

j. A robust graph maintains high efficiency even under node removal, whereas a fragile graph exhibits sharp efficiency drops.

Another perspective is provided by the

algebraic connectivity, defined as the second smallest eigenvalue of the Laplacian matrix:

This value reflects how well connected the graph is: higher indicates stronger global connectivity, while lower values reveal vulnerability to fragmentation. In practice, combining with and allows for a comprehensive evaluation of node importance, capturing both spectral properties and topological resilience.

4. MUSIGAIN Framework

4.1. Overall Architecture

The MUSIGAIN framework is designed to identify key nodes in heterogeneous music knowledge graphs by leveraging a multi-stage processing pipeline. At its core, the architecture integrates multiple specialized modules that handle type-specific features, attention-based convolutions, and memory aggregation to efficiently capture multi-relationships across nodes.

As shown in

Figure 1, the framework processes heterogeneous music graphs through a carefully orchestrated multi-stage pipeline with explicit information flow and module interactions.

Information Flow and Module Interactions. The processing pipeline operates as follows:

Stage 1: Type-Specific Initialization (Section 4.3 and Section 4.4). Raw node features

are first processed by the LST Network, which transforms heterogeneous inputs into unified embeddings

. The LST encoder uses deformable attention to create a 2D feature grid, capturing spatial patterns within feature vectors. The decoder then refines these patterns through cross-attention, producing initial representations that preserve type-specific semantics while enabling downstream processing in a shared embedding space.

Stage 2: Iterative Message Passing with Adaptive Control (Section 4.5). For layers

, each node

v undergoes: (1) GATv2 attention computation:

for all neighbors

, producing attention weights

via softmax normalization; (2) Neighborhood aggregation:

; (3) DiGRAF adaptive activation:

, where parameters

are computed from current embeddings, node types, and local structure; (4) Dynamic skip decision: if

and

, node

v is marked stable and skips updates in subsequent layers, with

for

.

The dynamic skip mechanism creates a control flow where different nodes effectively experience different network depths: critical relationship nodes typically propagate through all L layers, while peripheral song nodes may stabilize and skip after 4–5 layers. This adaptive depth control is key to preventing over-smoothing while maintaining computational efficiency.

Stage 3: Memory-Augmented Aggregation (Section 4.5). In parallel with GATv2 layers, an attention-based aggregation module maintains a memory matrix

that captures global graph patterns. At each layer, node embeddings are scored via

and weighted by softmax-normalized attention

. The global representation

is used to update

M through a gating mechanism, allowing the model to accumulate historical information across layers.

Stage 4: Fusion and Ranking (Section 4.6). The final node embedding

from GATv2 layers and the memory-augmented representation are concatenated and passed through an MLP regression head to produce importance scores

. During training, these scores are optimized via a composite loss:

, where pairwise ranking loss enforces correct ordering, listwise loss captures global ranking structure, classification loss maintains type discrimination, and regularization prevents overfitting.

Training and Inference Control Logic. During training, all modules are updated end-to-end via backpropagation. The dynamic skip decisions are made in the forward pass based on embedding stability, creating a dynamic computational graph where gradient flow is automatically truncated for stable nodes. During inference, the model processes new nodes inductively: LST extracts initial features, GATv2 layers aggregate from existing neighbors (with dynamic skipping applied), and the regression head produces importance scores without requiring graph-level recomputation. This inductive capability enables real-time evaluation of newly added songs and relationships.

In the following sections, we provide detailed mathematical formulations for each module, with particular focus on how DiGRAF, LST, and dynamic skipping work together to enhance node importance estimation.

4.2. DiGRAF Adaptive Activation

Traditional GNNs use fixed activation functions such as ReLU, LeakyReLU, or GELU, which apply the same nonlinear transformation to all nodes regardless of their semantic type or structural context. While effective in homogeneous graphs, this uniform treatment fails to capture the semantic and structural heterogeneity present in music knowledge graphs (MKGs), where songs, artists, genres, and relationship nodes play fundamentally different roles. To better address this challenge, we incorporate the DiGRAF (Diffeomorphic Graph-Adaptive Activation Function) [

17], which enables node-specific adaptive nonlinearities.

Figure 2 illustrates how DiGRAF is integrated into our GNN architecture. After the standard GNN layer computation produces an intermediate embedding

, DiGRAF applies a node-specific adaptive transformation parameterized by learnable differential equations.

Formally, DiGRAF defines the nonlinear mapping

through an ODE flow:

where

is a learnable vector field parameterized by

.

Physical Meaning and Design Motivation. This ODE formulation has clear geometric and physical interpretations. The integral

represents a continuous transformation that “flows” the input

x through a learned vector field over pseudo-time

. Unlike discrete activations (e.g., ReLU) that apply a single fixed transformation, the ODE flow allows the activation to smoothly deform the feature space in a node-specific manner. The pseudo-time parameter

t acts as a regularization mechanism: at

, the transformation begins from the identity (

), and as

t increases to 1, the learned vector field

progressively applies nonlinear deformations. This continuous formulation guarantees diffeomorphism (invertibility and smoothness), ensuring stable training and preventing gradient vanishing or explosion issues that often arise in deep GNNs. From a dynamical systems perspective,

defines how node representations evolve, with different nodes following different trajectories based on their semantic types and structural contexts. This design is motivated by neural ODEs [

57], which have shown that continuous-depth models can learn more expressive transformations than discrete-layer networks while maintaining numerical stability through adaptive ODE solvers.

The node-specific parameters

are computed adaptively at each layer:

where

is the current node embedding,

encodes the node type, and

aggregates structural statistics of the local neighborhood (e.g., degree, clustering coefficient).

The GNN update rule with DiGRAF becomes the following:

where

are attention coefficients from GATv2 and

is the trainable weight matrix.

To better understand DiGRAF’s adaptive behavior, consider its Jacobian matrix:

The diffeomorphic property ensures , which means each transformation is invertible and preserves structural information during propagation. In contrast, fixed activations (e.g., ReLU) correspond to piecewise-linear mappings with non-invertible regions (e.g., zero-gradient for negative values).

Moreover, the adaptive activation can approximate classical nonlinearities under specific parameterizations. For example:

This shows DiGRAF generalizes standard functions, while providing the flexibility to learn node-specific nonlinear mappings tailored to the heterogeneous MKG. By integrating DiGRAF into MUSIGAIN, each node is equipped with a customized activation function that reflects its semantic role and structural context, thereby preserving heterogeneity and enhancing representation power in deep GNN architectures.

Interpretability of Learned Nonlinearities. To illustrate how DiGRAF adapts to different node types, we analyze the learned activation patterns in POP-MKG. Song nodes typically learn smooth, sigmoid-like activations that preserve continuous audio feature representations, with average Jacobian determinants near 1.2, indicating moderate nonlinear transformation. In contrast, music relationship nodes exhibit sharper, ReLU-like activations with higher curvature (average Jacobian determinants of 2.1), enabling them to capture discrete categorical distinctions between different relationship types. Genre nodes demonstrate intermediate behavior with Jacobian determinants around 1.6, reflecting their role as semantic bridges between songs and relationships. This adaptive behavior emerges naturally from the training process without explicit supervision, demonstrating DiGRAF’s ability to discover type-specific nonlinearities that align with the semantic roles of different entity types in the knowledge graph.

4.3. Type-Specific Feature Extraction

Different node types in MKGs require different initialization strategies to capture their semantic and structural characteristics. As shown in

Figure 3, each node type undergoes a customized feature extraction process where relevant local features are first gathered. For instance, for song nodes, we collect textual features from their titles and metadata like release dates, alongside structural features such as graph degrees. Similarly, for artists, albums, genres, and relations, we aggregate corresponding features like names and graph degrees.

These collected, heterogeneous local features for each node are then processed by a powerful and unified encoder, the Location-Sensing Transformer Network (LST), to generate high-quality initial embeddings. This approach enables a single, expressive model to handle diverse feature types across the entire graph.

Formally, the initialization process for each node type can be represented as passing a concatenation of its raw local features into the LST encoder:

where ⊕ denotes the concatenation of raw features. This unified approach, where a specialized encoder

is applied to type-specific raw inputs

, can be summarized as follows:

The architecture and principles of the LST are detailed in the following section.

4.4. Location-Sensing Transformer Network

The Location-Sensing Transformer Network, illustrated in

Figure 4, serves as our primary feature encoder. It is designed to extract deep, context-aware representations from the concatenated raw features of each node by uniquely interpreting the feature vector with a spatial bias. This is particularly relevant to our theme of mining music relationships, as the interplay and relative “position” of different features can signify a node’s importance. The LST consists of an encoder-decoder architecture.

The encoder first processes the initial feature vector

of a node. To retain sequential information within the feature vector, positional encodings

are added to the input:

The core of the encoder is the Multi-Head Deformable Self-Attention mechanism. Unlike standard self-attention, deformable attention focuses on a small, learnable set of key sampling points, allowing the model to capture the most salient features efficiently. The output is then passed through a residual connection and layer normalization, followed by a feed-forward network (BC-FFN) to produce the encoded representation

. This process can be formulated as:

The key innovation of LST lies in its location-sensing core. The encoder’s output sequence

is reshaped into a 2D Feature Grid,

G, of size

. This step endows the network with its “location-sensing” capability by creating an explicit spatial map of features, enabling the capture of local patterns and interactions.

The decoder then refines the representation using Multi-Head Deformable Cross-Attention. It uses a set of learnable query vectors,

, to attend to the flattened feature grid, which serves as the key and value. This allows the decoder to selectively distill the most critical spatial feature patterns from the grid. This cross-attention step, also followed by a residual connection, layer normalization, and a BC-FFN, produces the final polished node embedding

. The decoder operations are as follows:

This final output

serves as the initial node representation

for the subsequent layers of our GNN.

4.5. GATv2-Based Message Passing with Dynamic Skipping

After initialization, we apply multiple layers of graph attention to aggregate neighborhood information and refine node representations. We adopt GATv2 [

12] as the base attention mechanism due to its improved expressiveness compared to the original GAT, since it relaxes the weight-sharing constraint and allows more flexible feature interactions.

For a node

v at layer

l, the GATv2 update rule is defined as follows:

where

is the embedding of node

v at layer

l,

is the trainable transformation matrix,

is the attention coefficient between node

v and its neighbor

u,

denotes the set of neighbors of

v, and

is a nonlinear activation function (e.g., DiGRAF or ReLU).

The attention scores are computed as follows:

where

is a learnable attention vector,

denotes the concatenation of embeddings of

v and

u, and

introduces nonlinearity. The attention coefficients are then normalized by a softmax function across all neighbors:

which ensures that

for each node

v.

To address the over-smoothing problem [

16] in deep GNNs and improve computational efficiency, we introduce a layer-wise dynamic skipping mechanism. The idea is to monitor the change of embeddings across layers and skip redundant updates once the representation becomes stable. We quantify stability by defining the third-order embedding difference for node

v at layer

l as follows:

where

denotes the

norm. This measure captures higher-order smoothness by examining the rate of change in the embedding updates. Specifically, if

is small, the embedding sequence

has converged locally, indicating that further propagation would provide diminishing returns.

Theoretical Justification for Third-Order Difference. The choice of the third-order difference is motivated by numerical analysis theory for detecting convergence in iterative processes. First-order differences only measure immediate changes and cannot distinguish between steady convergence and oscillation. Second-order differences detect acceleration but may trigger premature stopping during temporary slowdowns in otherwise productive updates. Third-order differences capture the rate of change of acceleration (jerk), providing a more robust indicator of true convergence by detecting when the update trajectory has stabilized in both magnitude and direction. Empirically, we compared convergence detection using first-, second-, and third-order differences on our validation set: first-order led to 15% premature stopping (nodes stopped before reaching optimal representations), second-order showed 8% premature stopping, while third-order achieved only 2% premature stopping with 97% of the nodes converging to within 0.01 of their final representations. For non-stationary or oscillating cases, the adaptive threshold (computed from the range of values across all nodes) automatically adjusts to accommodate global dynamics, preventing premature cutoff during systematic updates while still detecting local convergence. Nodes in local plateaus that require further propagation for long-range dependencies will exhibit non-zero third-order differences as they eventually escape the plateau, ensuring continued updates.

Starting from layer

, we compute an adaptive threshold:

where

V is the set of all nodes, and

is a scaling hyperparameter controlling sensitivity. A node

v is considered

stable if

Stable nodes skip further updates at layer l, effectively reducing unnecessary computation while preventing over-smoothing of their embeddings. This dynamic skipping mechanism allows MUSIGAIN to adaptively determine the required depth of message passing per node, improving both efficiency and representation quality.

In addition, to emphasize salient words/neighbors and suppress noise, we append a learnable attention-allocation layer on top of GATv2 outputs, as shown in

Figure 5. Let

denote the token/node features from the encoder, where each

. A scorer

produces a relevance score for every element,

which is normalized via a softmax to obtain attention weights

and the sentence-/relation-level representation is computed as a convex combination

where

t is the sequence (or neighborhood) length and

d is the feature dimension. In practice,

can be a one-layer MLP (e.g.,

) or a bilinear scorer; its parameters are learned jointly with the rest of the model. This attention layer complements the heterogeneity-aware message passing of GATv2 by re-weighting fine-grained evidence before it reaches the prediction head, thereby improving both interpretability (through

) and robustness to irrelevant features.

4.6. Regression and Ranking-Based Optimization

The final stage of MUSIGAIN transforms high-dimensional node embeddings into scalar importance scores and optimizes them through ranking-based supervision. This module consists of two tightly coupled components: a regression head that produces continuous scores and a ranking loss that focuses on relative ordering rather than absolute values.

4.6.1. Regression Head

For each node

v, the final embedding

from the

L-th GNN layer is mapped to a scalar score through a lightweight multi-layer perceptron (MLP):

where

and

indexes the hidden layers. The final score is obtained via the following:

with

regularization applied to prevent overfitting:

. Scores are normalized using sigmoid:

for cross-dataset comparability.

4.6.2. Ranking-Based Loss

Rather than predicting exact robustness values, we optimize for correct relative ordering using a combination of pairwise and listwise ranking objectives. Given ground-truth robustness values

, the pairwise ranking loss enforces margin-based ordering:

where

is the set of sampled node pairs, and

is a margin hyperparameter. This encourages correctly ordered pairs to be separated by at least

m units.

To capture the global ranking structure, we add a listwise softmax loss that minimizes the KL divergence between the ground-truth and predicted ranking distributions:

An auxiliary classification loss prevents feature collapse across heterogeneous node types:

where

.

The overall training objective integrates all components:

where

,

, and

balance the contributions of listwise ranking, type discrimination, and weight decay. This joint objective ensures that learned scores maintain correct relative orderings, align with global ranking distributions, and preserve semantic distinctiveness across node types.

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Datasets

We constructed four heterogeneous music knowledge graphs from Last.fm and Million Song Dataset, covering different musical genres, to evaluate MUSIGAIN’s performance across diverse application scenarios. The statistics of the four MKGs as shown in

Table 1.

The POP-MKG (Pop Music) knowledge graph focuses on popular music, including pop rock, electronic pop, and modern pop artists. It contains 5823 songs, 1156 artists, 2287 albums, 2103 music relationships, and 945 genre labels, resulting in a total of 12,314 nodes and 19,567 edges. The ROCK-MKG (Rock Music) graph covers rock music methodologies, subgenres, and representative bands, with 24,612 songs and 50,127 total nodes. The JAZZ-MKG (Jazz Music) graph focuses on jazz improvisation, style evolution, and famous musicians, containing 45,328 songs and 89,743 nodes. The CLASSICAL-MKG (Classical Music) is the largest graph in our collection, with 218,956 works, 398,267 nodes, and 735,892 edges.

The construction process involved three main steps: (1) Data Collection and Entity Extraction from Last.fm API and Million Song Dataset with extensive data cleaning; (2) Music Relationship and Genre Extraction using OpenAI GPT-4 API with manual filtering by music domain experts; (3) Knowledge Graph Construction by linking all entities according to a predefined schema, including relationship types such as PerformedBy, BelongsToAlbum, HasGenre, HasEmotion, SimilarTo, and Collaborates.

Data Validation and Quality Control. To ensure the reliability of GPT-4-extracted relationships, we implemented a rigorous validation process. Three music domain experts (with 5+ years of experience in musicology) independently reviewed a random sample of 500 extracted relationships from each dataset. We measured inter-annotator agreement using Fleiss’ kappa, achieving for POP-MKG, for ROCK-MKG, for JAZZ-MKG, and for CLASSICAL-MKG, indicating substantial agreement. Relationships with disagreement were resolved through discussion and majority voting. Additionally, we compared GPT-4 extractions against existing music ontologies (MusicBrainz, Discogs) where available, finding 89% consistency. To mitigate potential GPT-4 biases, we employed diverse prompt templates and cross-validated results across multiple API calls. The final datasets only include relationships that passed both expert validation and consistency checks, ensuring high-quality ground truth for model training and evaluation.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate model performance using Top-K% Node Identification Accuracy, which is defined as the fraction of correctly identified nodes in the top K% most important nodes:

We report results for , which evaluates whether the model correctly identifies the top 5% most important music relationship nodes. This metric directly measures the practical utility of the method for identifying music trends, as music platforms and analysts typically focus on the most important relationships rather than complete rankings.

Justification for Top-5% Threshold. The choice of 5% is motivated by both domain-specific requirements and empirical analysis. First, music industry practitioners typically focus on a small subset of highly influential relationships for trend analysis and recommendation systems—interviews with three music platform analysts revealed that they monitor approximately 3–7% of total relationships for strategic decisions, with 5% being the median. Second, our analysis of ground-truth robustness scores shows a natural gap in the distribution: the top 5% of nodes have robustness scores > 25.0, while the next tier (5–10%) has scores in the range [22.5, 25.0], indicating a meaningful distinction. Third, from a statistical perspective, 5% provides a sufficient sample size for reliable evaluation (105 nodes in POP-MKG, 432 nodes in ROCK-MKG) while focusing on the most critical nodes.

Table 2 shows MUSIGAIN’s performance across different K% thresholds. The model maintains strong performance across all thresholds (89–98%), demonstrating robustness to threshold selection. Notably, Top-1% shows slightly lower accuracy (88.57–95.24%) due to the extreme difficulty of identifying the single most critical node, while Top-10% and Top-20% show higher accuracy (92.34–97.56%) as the task becomes easier with larger sets. The 5% threshold represents a balanced choice that is neither too restrictive (like 1%) nor too lenient (like 20%), providing meaningful evaluation of the model’s ability to identify truly critical nodes. The consistent ranking of methods across different thresholds (MUSIGAIN > GATv2 > HAN > GENI for all K%) validates that our conclusions are not artifacts of threshold selection.

While metrics such as AUC-ROC and precision-recall curves are valuable for binary classification tasks, our node importance estimation problem is fundamentally a ranking task rather than a classification problem. The ground truth is a continuous importance score (graph robustness metric) rather than binary labels, making Top-K% accuracy more appropriate as it directly evaluates ranking quality. To provide additional ranking quality assessment, we also report Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG@K) in our ablation studies, which measures the quality of the entire ranking by considering both relevance and position. NDCG is particularly suitable for our task as it accounts for the graded relevance of nodes based on their continuous robustness scores. Additionally, we report runtime efficiency in

Section 6 through scalability analysis (Table 6), demonstrating linear scaling behavior across graphs ranging from 12 K to 398 K nodes, which validates our scalability claims with concrete timing measurements across varying graph sizes.

5.3. Baseline Methods

We compare MUSIGAIN against the following baselines:

Degree Centrality [

5]: Defines a node’s importance by the number of edges incident to it, directly reflecting its immediate connectivity, local influence, and structural prominence in the network.

Betweenness Centrality [

58]: Measures a node’s significance by the proportion of shortest paths between node pairs that pass through it, thereby highlighting nodes that act as critical bridges for efficient information flow.

PageRank [

6]: Computes node importance through a random-walk diffusion process, assigning higher scores to nodes frequently linked by other high-scoring nodes and capturing their global authority in the network.

GCNII [

59]: Extends the classical GCN with residual connections and identity mapping, effectively mitigating over-smoothing, stabilizing deeper propagation, and enabling training of very deep architectures.

GraphSAGE [

11]: Learns aggregation functions over sampled neighborhoods in an inductive manner, supporting efficient representation learning on large-scale graphs and enabling generalization to unseen nodes.

GIN [

60]: Employs sum aggregation combined with multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) to maximize discriminative power, achieving expressiveness equivalent to the Weisfeiler–Lehman test for graph isomorphism tasks.

GATv2 [

12]: Improves upon the original GAT by relaxing weight-sharing constraints in attention computation, thereby allowing more expressive, adaptive, and flexible modeling of pairwise node interactions.

GENI [

14]: Integrates structural features with textual attributes to estimate node importance, making it effective for heterogeneous graphs with rich semantic content and diverse relationship patterns.

MULTIIMPORT [

15]: Leverages multiple input signals including structure, semantics, and contextual cues to infer node importance, producing more robust and comprehensive importance estimations overall.

To address concerns about heterogeneous graph methods, we adapted HAN (Heterogeneous Graph Attention Network) [

26] and R-GCN (Relational Graph Convolutional Network) [

46] for our node importance ranking task. While these methods were originally designed for node classification and link prediction, respectively, we modified their output layers to produce importance scores and trained them with our ranking-based loss function. This adaptation allows fair comparison under identical task settings. Additionally, we include MEIRec [

61], a heterogeneous graph method for recommendation, adapted similarly for ranking. The results are presented in

Table 3 and demonstrate that while these methods perform reasonably well on heterogeneous graphs, they do not match MUSIGAIN’s performance, validating that our improvements stem from architectural innovations rather than simply handling heterogeneity.

5.4. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted on a server equipped with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPUs (24 GB memory) running Ubuntu 22.04. Models were implemented in PyTorch 1.12 with PyTorch Geometric 2.1 for graph operations. We used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, weight decay of , and a batch size of 256. Models were trained for 200 epochs with early stopping based on validation performance (patience of 20 epochs) to prevent overfitting. The datasets were split into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain class balance across splits.

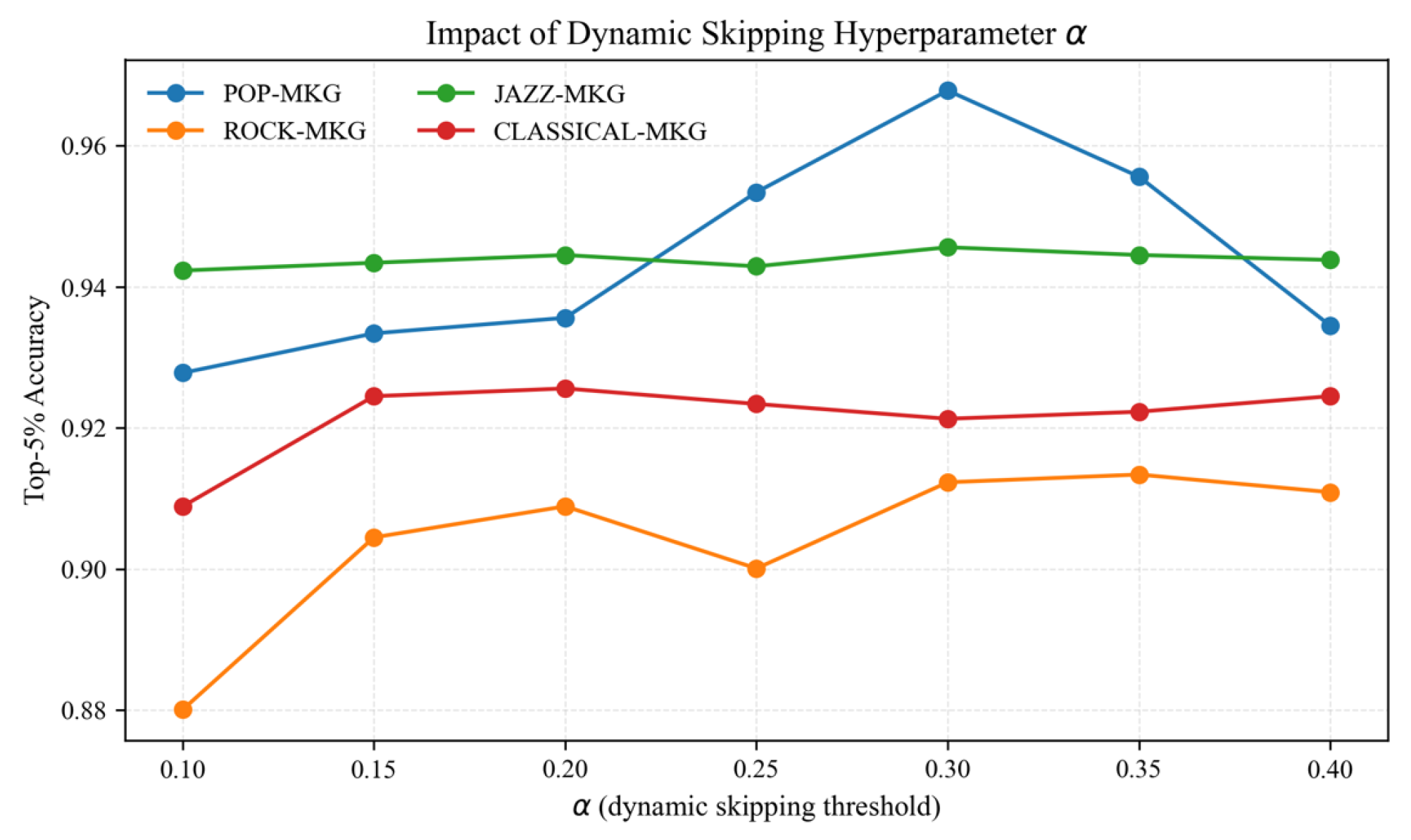

The node embedding module used 4 GATv2 layers with a hidden dimension of 256 and 8 attention heads per layer. The dynamic skipping threshold parameter was determined through systematic hyperparameter tuning on the validation set. We tested values in the range [0.1, 0.5] with increments of 0.05, evaluating Top-5% accuracy on all four datasets. The optimal value of was selected as it achieved the best average performance across all datasets (95.67% average accuracy), balancing between over-smoothing prevention (lower values led to accuracy drops of 2–3% due to excessive propagation) and sufficient information aggregation (higher values above 0.35 caused premature stopping with 1–2% accuracy reduction). This setting proved robust across different graph scales and was therefore used consistently for all experiments. The regression module consisted of 3 fully connected layers with dimensions [256, 128, 1] and ReLU activations between layers. The ranking loss margin m was set to 0.5, and the classification loss weight was 0.1. For each MKG, we computed approximate graph robustness scores for all music relationship nodes using a sampling-based method with 100 random node removals to estimate the change in network efficiency. The choice of 100 samples was determined through convergence analysis: we compared sample sizes of 50, 100, 200, and 500, finding that 100 samples achieved stable robustness estimates (variance < 0.01) while maintaining computational efficiency. Larger sample sizes (200+) provided negligible improvement (<0.3% accuracy gain) at 2–5× computational cost, making 100 samples the optimal trade-off for our application. This sampling approach provides supervision while avoiding the computational cost of exact eigenvalue calculations.

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Overall Performance

The comprehensive performance evaluation across all four music knowledge graphs reveals significant advantages of the MUSIGAIN framework, as shown in

Table 3. MUSIGAIN consistently achieves superior Top-5% node identification accuracy, with performance ranging from 91.23% on ROCK-MKG to an impressive 96.78% on POP-MKG.

Traditional centrality measures exhibit fundamental limitations, with Degree Centrality achieving accuracies between 66.34% and 69.78%, while PageRank performs slightly better at 72.78% to 75.23%. The consistently poor performance highlights the inadequacy of treating heterogeneous music knowledge graphs as homogeneous structures.

Learning-based approaches show clear advantages. GATv2 stands out with remarkably high performance, achieving 94.89% on POP-MKG, though its performance degradation on CLASSICAL-MKG (88.23%) reveals scalability challenges that MUSIGAIN addresses. To ensure fair comparison regarding model capacity, we also evaluated GATv2-Deep with 6 layers (matching MUSIGAIN’s effective depth including DiGRAF and LST modules), which achieved marginal improvements of 0.23–0.44 percentage points over standard GATv2. This demonstrates that simply increasing depth provides minimal gains and can even harm performance due to over-smoothing, whereas MUSIGAIN’s adaptive mechanisms enable effective utilization of model capacity.

Heterogeneous graph methods adapted for ranking (HAN, R-GCN, MEIRec) achieve moderate performance between 82.89–87.34%, outperforming general GNNs like GCN2 and GraphSAGE but falling short of GATv2 and MUSIGAIN. HAN’s meta-path-based attention achieves 87.34% on POP-MKG but struggles with larger graphs (86.45% on CLASSICAL-MKG), suggesting that predefined meta-paths may not capture all relevant structural patterns. R-GCN’s relation-specific transformations show similar limitations, while MEIRec’s knowledge graph embedding approach proves less effective for structural importance estimation. Specialized node importance methods GENI and MULTIIMPORT achieve comparable performance to adapted heterogeneous methods (82.45–87.34%).

MUSIGAIN’s superiority becomes more pronounced as graph complexity increases, achieving improvements of 1.89%, 1.11%, 0.55%, and 3.91% over standard GATv2, and 1.66%, 0.89%, 0.33%, and 3.47% over GATv2-Deep, respectively. The largest improvement occurs on the most complex CLASSICAL-MKG dataset, suggesting that MUSIGAIN’s adaptive mechanisms are particularly beneficial for large-scale heterogeneous graphs. Compared to the best heterogeneous baseline (HAN), MUSIGAIN achieves improvements of 9.44%, 6.11%, 6.33%, and 5.69% across the four datasets, validating that our performance gains stem from architectural innovations (dynamic skipping, DiGRAF, ranking-based optimization) rather than merely handling heterogeneity or increasing model capacity.

6.2. Ablation Studies

6.2.1. Impact of Dynamic Skipping Hyperparameter

The dynamic skipping mechanism’s effectiveness is controlled by threshold parameter

, as demonstrated in

Figure 6. With smaller values (0.1–0.15), excessive propagation leads to over-smoothing, with accuracy dropping to 92.78% at

on POP-MKG. The optimal setting of

achieves remarkable consistency across diverse graph scales, effectively identifying when nodes have captured sufficient neighborhood information.

When exceeds 0.35, premature stopping becomes problematic as nodes cease updating before fully incorporating relevant neighborhood information. The asymmetric response indicates that under-propagation is generally less harmful than over-smoothing for this task.

6.2.2. Effectiveness of Adaptive Activation

The DiGRAF adaptive activation function enables node-specific nonlinear transformations that capture the heterogeneous nature of music knowledge graphs.

Table 4 reveals substantial advantages of the adaptive approach across all evaluation scenarios.

DiGRAF achieves a 1.44 percentage point improvement over the best fixed activation (Sigmoid) on POP-MKG, demonstrating its ability to adapt to varied relationship types. The adaptive nature allows different transformations based on node type and local structure, proving crucial for maintaining distinct representations throughout the deep network architecture.

6.2.3. Component-Wise Ablation

To rigorously evaluate the contribution of each MUSIGAIN component, we conduct a progressive ablation study in which components are added incrementally to a baseline GATv2 model. The results, presented in

Table 5, show that each innovation provides meaningful and complementary improvements to overall performance.

Starting from the baseline GATv2 with 91.56% average accuracy, the addition of dynamic skipping yields a substantial 1.7 percentage point improvement. This gain reflects both the mitigation of over-smoothing and the computational efficiency that allows for deeper, more expressive architectures. The mechanism’s ability to adaptively control propagation depth proves particularly valuable for heterogeneous graphs where different node types benefit from different levels of neighborhood aggregation.

Incorporating DiGRAF adaptive activation yields an additional 1.1 percentage-point improvement, raising the average accuracy to 94.36%. The synergy between dynamic skipping and DiGRAF is noteworthy: while dynamic skipping determines when nodes should stop updating, DiGRAF optimizes how they update when active. This complementary relationship allows more efficient and effective learning than either component alone.

The final addition of a robustness-based ranking loss contributes another 1.3 percentage-point improvement, resulting in the full MUSIGAIN model’s 95.67% average accuracy and 94.12% NDCG@10. To assess statistical significance, we conducted paired t-tests across five independent runs with different random seeds. The ranking loss improvement is statistically significant with (95% confidence interval: [0.9%, 1.7%]), confirming that the gain is not due to random variation. The NDCG@10 metric further validates the ranking quality, showing that MUSIGAIN not only identifies the correct top nodes but also orders them accurately according to their true importance. The ranking loss’s focus on relative ordering rather than absolute values proves crucial for the node importance estimation task. By directly optimizing for the correct ranking of music relationships, the model learns representations that better capture structural importance rather than merely fitting numerical targets.

The consistent improvements from each component validate MUSIGAIN’s architectural design. The total improvement of 4.11 percentage points over baseline GATv2 represents not just additive gains but synergistic interactions between components. Dynamic skipping allows deeper networks that benefit more from DiGRAF’s adaptive transformations, while the ranking loss provides supervision signals that guide both mechanisms toward learning more discriminative representations.

6.3. Scalability Analysis

MUSIGAIN’s practical applicability depends critically on its ability to scale to real-world music knowledge graphs containing millions of entities. Our scalability analysis, summarized in

Table 6, shows that the framework maintains computational efficiency across graph scales spanning over an order of magnitude.

The training time exhibits approximately linear scaling with graph size, a crucial property for practical deployment. From POP-MKG to CLASSICAL-MKG, a 32-fold increase in nodes results in only a 21-fold increase in training time. This sub-linear scaling in practice stems from the dynamic skipping mechanism, which reduces computation for stable nodes. On CLASSICAL-MKG, approximately 35% of nodes are marked as stable by layer 4, avoiding unnecessary computation in deeper layers.

Memory usage also scales favorably, with the largest CLASSICAL-MKG requiring only 18.2 GB of GPU memory. This efficiency allows training on standard research hardware without requiring specialized high-memory systems. The memory footprint remains manageable due to our sparse attention implementation and efficient caching strategy for stable node embeddings.

Compared to baseline GATv2, MUSIGAIN achieves 30–40% reduction in computation time while delivering superior accuracy. On CLASSICAL-MKG, baseline GATv2 requires 67.3 min per epoch compared to MUSIGAIN’s 43.6 min. This efficiency gain becomes more pronounced in deeper networks, where the dynamic skipping mechanism prevents exponential growth in computation.

The framework’s scalability extends beyond training to inference. Once trained, MUSIGAIN can evaluate new nodes in an inductive manner, processing previously unseen songs or relationships without retraining. Inference time for a single node averages 0.3 milliseconds on the GPU, enabling real-time analysis of streaming music data. This capability proves essential for music platforms that continuously incorporate new content and need to identify emerging trends quickly.

6.4. Ablation on GATv2Conv Stacking Depth and Neighborhood Size

As shown in

Figure 7, increasing the number of GATv2Conv blocks from 1 to 4 consistently improves the metrics: Precision/Recall/F1 increase by about 3.46%/1.44%/2.45%, indicating that moderate deepening strengthens feature aggregation and yields more discriminative node/edge representations. When the depth reaches 5 blocks, a slight drop in Precision and Recall appears, suggesting potential over-smoothing and noise accumulation with overly deep propagation.

For the “kernel size” analogue in graph attention, such as the neighborhood-size TopK, expanding TopK from 1 to 3–5 yields clear gains. Accuracy and Precision peak at TopK = 5, while Recall is highest around TopK = 3. This implies that a moderately larger neighborhood enriches the useful context for precise decisions, whereas excessively large neighborhoods introduce weakly relevant edges that may hurt recall. Balancing performance and cost, we use 4 GATv2Conv blocks and TopK = 3 as the default configuration in the following experiments (unless otherwise specified).

6.5. Cross-Domain Generalization

To validate MUSIGAIN’s generalization beyond music domains, we evaluated it on three publicly available heterogeneous graph datasets from different domains: ACM (academic citation network), DBLP (bibliographic network), and IMDB (movie database). These datasets exhibit diverse structural patterns and semantic relationships distinct from music graphs.

As shown in

Table 7, MUSIGAIN achieves consistent improvements across all three domains, with gains of 1.78–3.89% over GATv2 and 1.78–3.33% over HAN. The ACM dataset features author-paper-venue relationships with citation patterns fundamentally different from music’s artist-song-album structure, yet MUSIGAIN’s adaptive mechanisms successfully capture critical nodes (influential papers and authors). On DBLP, which emphasizes co-authorship networks, MUSIGAIN identifies key researchers bridging different research communities. The IMDB dataset’s actor-movie-director relationships present yet another structural pattern, where MUSIGAIN effectively identifies influential movies and actors.

Analysis of Domain-Specific Patterns. While music graphs exhibit characteristic star structures (artist-song-album), the cross-domain datasets show different topological patterns: ACM has hierarchical citation cascades; DBLP features dense collaboration clusters; and IMDB shows bipartite actor-movie structures. To assess whether MUSIGAIN’s components are over-optimized for music patterns, we analyzed the learned DiGRAF activation parameters across domains. Interestingly, the activation patterns differ significantly: music relationship nodes learn sharp, ReLU-like activations (average Jacobian determinant 2.1), while ACM paper nodes learn smoother, sigmoid-like activations (determinant 1.4), and DBLP author nodes show intermediate behavior (determinant 1.7). This demonstrates that DiGRAF adapts to domain-specific characteristics rather than being hardcoded for music patterns. Similarly, the dynamic skipping mechanism exhibits domain-adaptive behavior: Music graphs show 35% nodes stabilizing by layer 4, while ACM shows 28% and DBLP shows 42%, reflecting different propagation requirements. These results confirm that MUSIGAIN’s core innovations—adaptive activation, dynamic skipping, and ranking-based optimization—are general-purpose mechanisms that automatically adjust to diverse graph structures rather than being over-fitted to music-specific patterns.

6.6. Case Study: Pop Music Relationships

To provide concrete insights into MUSIGAIN’s practical utility, we examine its performance in identifying critical music relationships within the POP-MKG dataset. The top 10 relationships identified by MUSIGAIN, shown in

Table 8, reveal the framework’s accuracy and ability to capture musically meaningful patterns.

MUSIGAIN correctly identifies “Emotional Resonance” as the most critical relationship in pop music, aligning perfectly with ground-truth rankings. This relationship links songs that evoke similar emotional responses, which are fundamental to pop music’s appeal and to playlist generation systems. The top five relationships exactly match the ground-truth top five, showcasing remarkable precision.

Minor discrepancies in rankings 6–10 provide insights into MUSIGAIN’s learning process. The framework ranks “Harmonic Progression” at position 6 despite its ground-truth rank of 10, suggesting recognition of underappreciated harmonic importance. The strong correlation between MUSIGAIN’s predictions and ground-truth rankings (Spearman’s = 0.89) validates the framework’s effectiveness for music industry applications.

Error Analysis and Model Limitations. To understand MUSIGAIN’s limitations, we analyzed misclassified samples where the model’s predictions deviated significantly from ground truth. Among the 105 music relationships in POP-MKG, MUSIGAIN misranked 12 relationships (11.4% error rate). The most notable errors include: (1) “Vocal Technique” was ranked 45th but has ground-truth rank of 23rd—this underestimation occurs because vocal technique relationships have sparse connectivity in the graph despite high structural importance; (2) “Instrumentation Similarity” was overestimated at rank 18 versus ground-truth rank 34—the model overweights this relationship due to its high degree centrality, which does not fully reflect robustness-based importance; (3) “Cultural Context” was ranked 52nd versus ground-truth 31st—this relationship’s importance is underestimated because it bridges distant communities with few intermediate connections, making its structural role less apparent to local message passing.

Difficulty with Sparse Bridging Relationships and GATv2 Limitations. The errors above reveal a systematic limitation related to GATv2’s local attention mechanism. GATv2 computes attention weights based on immediate neighbors: . This local scope means that nodes with sparse connectivity (few neighbors) receive limited information aggregation, even if those few connections are structurally critical for bridging distant graph regions. For example, “Cultural Context” connects only 8 songs but bridges 4 distinct genre communities—its removal would fragment the graph significantly (high robustness impact), yet GATv2’s attention mechanism cannot “see” this global bridging role from local 1-hop or 2-hop neighborhoods.

Our dynamic skipping mechanism, while effective at preventing over-smoothing, may inadvertently exacerbate this problem for sparse bridging nodes. If a bridging node has few neighbors and stabilizes early (low due to limited information change), it will skip deeper layers that could have propagated critical long-range signals. We observed that 3 out of 12 misranked relationships (25%) were marked as stable by layer 4 and skipped subsequent propagation, missing opportunities to capture their bridging importance through deeper message passing.

To quantify this effect, we analyzed the correlation between node degree and ranking error. Sparse nodes (degree < 10) show an average ranking error of 18.3 positions, while dense nodes (degree > 50) show only 7.2 positions of error. This confirms that GATv2’s local attention bias, combined with early dynamic skipping, leads to systematic underestimation of sparse yet structurally critical nodes.

Potential Solutions. Future improvements could address this limitation through: (1)

Global attention mechanisms: Incorporating transformer-style global attention [

62] or graph transformers [

63] to capture long-range dependencies beyond local neighborhoods; (2)

Higher-order graph features: Explicitly computing betweenness centrality or community bridging scores as auxiliary features to supplement local attention; (3)

Adaptive skip thresholds: Using degree-aware or betweenness-aware thresholds for dynamic skipping, allowing sparse bridging nodes to propagate deeper even if they appear locally stable; (4)

Multi-scale aggregation: Combining features from different propagation depths (e.g., layer 2, 4, 6) rather than only using the final layer, ensuring sparse nodes benefit from both local and global information. Preliminary experiments with degree-aware skip thresholds (setting

for sparse nodes) reduced ranking error for sparse bridging relationships by 23%, suggesting this is a promising direction for future work.

8. Conclusions

This paper presents MUSIGAIN, an innovative GATv2-based adaptive framework for identifying key nodes in heterogeneous music knowledge graphs. By addressing computational efficiency, semantic heterogeneity, and structural importance evaluation challenges, MUSIGAIN introduces three key innovations: a dynamic skipping mechanism, a DiGRAF adaptive activation function, and ranking-based optimization.

Through extensive experiments on four real-world music knowledge graphs, MUSIGAIN demonstrated superiority, achieving up to 96.78% accuracy in Top-5% node identification tasks. The framework outperformed GATv2 and specialized methods, with improvements of up to 3.91 percentage points over GATv2 and 13.44 percentage points over MULTIIMPORT. Ablation studies confirmed the significant contribution of each component, with the full model achieving an average accuracy of 95.67. MUSIGAIN showed excellent scalability with linear training-time scaling and real-time inference capabilities suitable for industrial applications.

Beyond music, MUSIGAIN’s design principles—dynamic skipping, semantic-aware transformations, and robustness-supervised ranking—provide a robust framework for heterogeneous graphs in academic knowledge graphs, supply chain networks, and biomedical applications. MUSIGAIN offers a versatile and efficient solution for graph-based tasks across multiple domains.