2. Holonic Manufacturing

Research on holonic manufacturing control architectures has revealed methodologies and frameworks designed to integrate tactics and processes that ensure system resilience when confronted with unforeseen alterations. This facilitates enhanced system robustness, a trait observed in natural systems, drawing a parallel to the industrial environment. Following the deficiencies identified in existing frameworks and investigations, a clear necessity has emerged to formulate a Holonic proposition for the restructuring of manufacturing systems.

This proposition should address the shortcomings of contemporary models, thereby offering substantial advancements in incorporating sustainability considerations, hierarchical structures, and multi-scalar perspectives, aligning with the aims of the 2030 Agenda and leveraging digitization. Furthermore, the suggested holonic architecture builds upon the tenets of Industry 4.0 through the application of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), positioning the holonic manufacturing system (HMS) as an organizational facilitator that manages the increasing intricacy of modern manufacturing environments. This system seamlessly integrates and utilizes the advantages provided by digital and technological facilitators, promoting a vision for the restructuring of sustainable cognitive manufacturing.

The holonic management approach can subsequently use these parts of communication and data collection in principle [

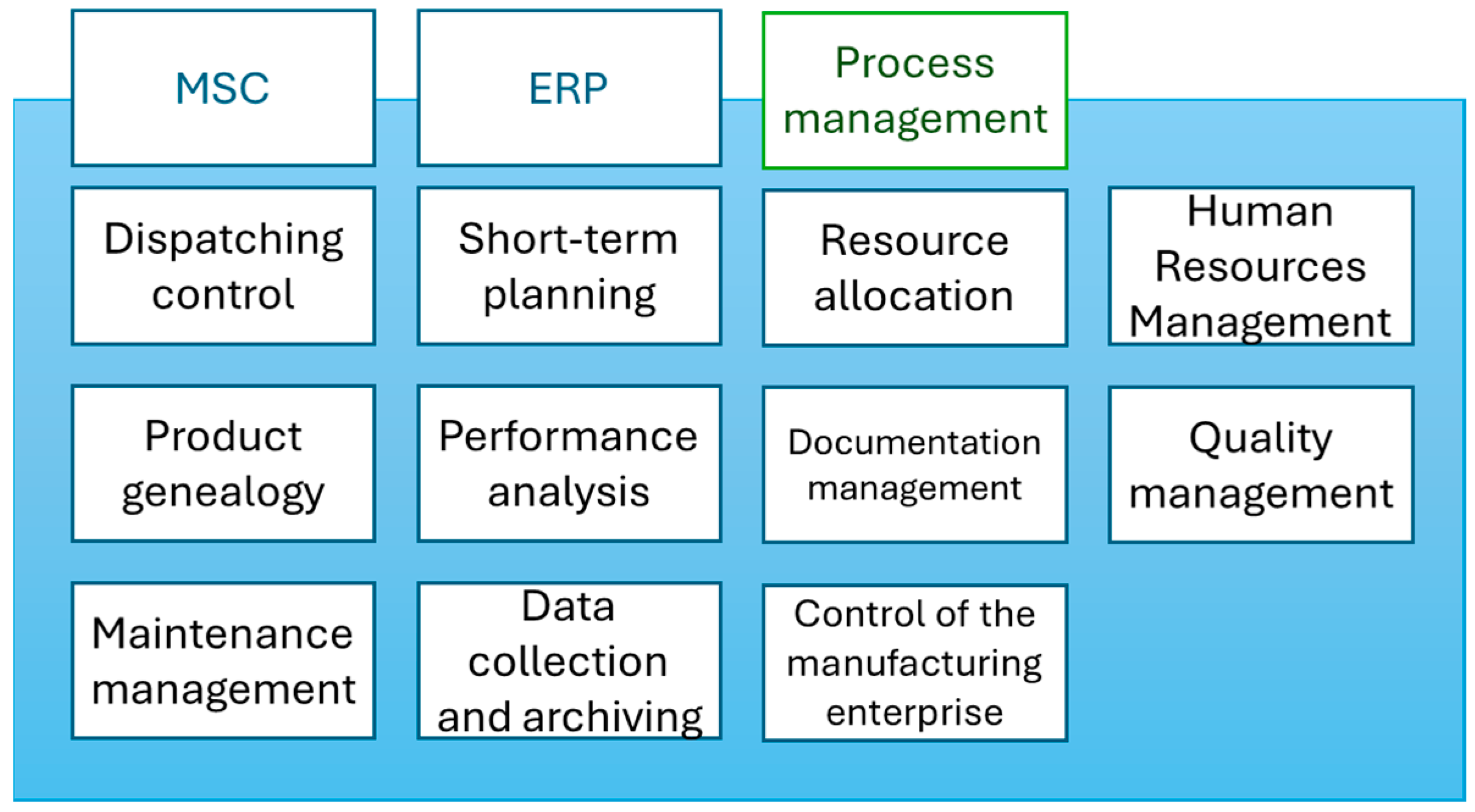

7]. It represents a different approach to evaluating and managing production, which can use standard information or industrial protocols. The subject and content areas of the analysis of the current state in this paper are presented in

Figure 1.

Automation area—understanding the principles of operation of industrial communication standards [

8], buses, and control systems. Their possibilities and scope of optimal use for specific applications in conjunction with intelligent sensors, which are becoming increasingly affordable [

9].

The area of data network design and engineering, topology, and hierarchical arrangement of nodes. This information and knowledge will ensure optimal connection of information systems with production units, not only within the company [

10], but also from the point of view of collecting and sharing information between production layouts located at distances exceeding the range of the local data network.

The area of communication interfaces of information systems, their possibilities of use, and their mutual integration. This is a rapidly growing area with the aim of making functionality and data available for cooperation with other systems in the network [

11]. This area is described in more detail in the proposed methodology and addresses the design of communication between information systems, together with the process level.

A key characteristic of manufacturing system development is constant and open innovation fueled by diverse technologies. This necessitates minimizing environmental and social impact through strategies focused on reducing the concentration and complexity of biological resources in the natural environment and technical resources in the technological environment. Addressing this demand requires a long-term support (LTS) framework capable of providing solutions that endure beyond typical lifecycles. This framework must account for continuous innovation, the necessary diversity, environmental responsibility, and complex multi-level and multi-scale interactions, ensuring adaptability and co-evolution. The holonic architecture provides a potential response to these needs.

The holonic paradigm builds upon the work of Arthur Koestler, who proposed a model for understanding the structure and behavior of complex systems. He viewed these systems as being composed of entities that are simultaneously complete units and component parts. In a social organizational context, a holon functions as a component of a larger entity and as a complete entity with its own components, depending on the frame of reference. Koestler also introduced the concept of the Open Edges Hierarchy (OEH), a holarchy architecture formed by holons, which is structurally unbounded both in its lower and upper tiers [

11].

Early applications of holonic architecture in manufacturing originated with Japanese researchers in the 1980s, focusing on the design and implementation of a holonic controller for a manipulator. Hirose et al. presented this design and subsequently described the associated software. A prototype implementation for the manipulator was showcased in 1990. The benefits identified through the application of the holonic paradigm included a more resilient design due to simplified wiring and improved manipulator reliability. The manipulator control software necessitated coordination among internal controllers through dedicated task managers and message exchange, a typical feature of holonic control software [

12].

The idea of using the holonic concept in manufacturing systems emerged around 1990 in the IMS(s) program as a solution to cope with the increasing intensity of changes that were affecting the entire economic world, including the manufacturing sector. The HMS Consortium (HMSC), consisting of researchers from Australia, Canada, Europe, Japan, and the United States, was established within the IMS program to develop tools for implementing the holonic concept in manufacturing areas and thus achieve the advantages of holonic organizational structures, such as “tolerance to failures, adaptability to changes and efficient use of available production resources” [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The HMS Consortium introduced a series of working definitions for individual entities of a holonic system:

Figure 2.

Holonic process formation [

20].

Figure 2.

Holonic process formation [

20].

Although multi-agent and holonic architectures have been extensively studied, particularly regarding coordination, interoperability, and distributed control, existing approaches typically rely on heterogeneous or domain-specific communication mechanisms that hinder ease of integration across industrial systems. While REST-based interfaces are widely used in software engineering, their systematic application as a unifying abstraction layer for agent–holon interaction has not been thoroughly examined in the context of manufacturing control.

Hsieh [

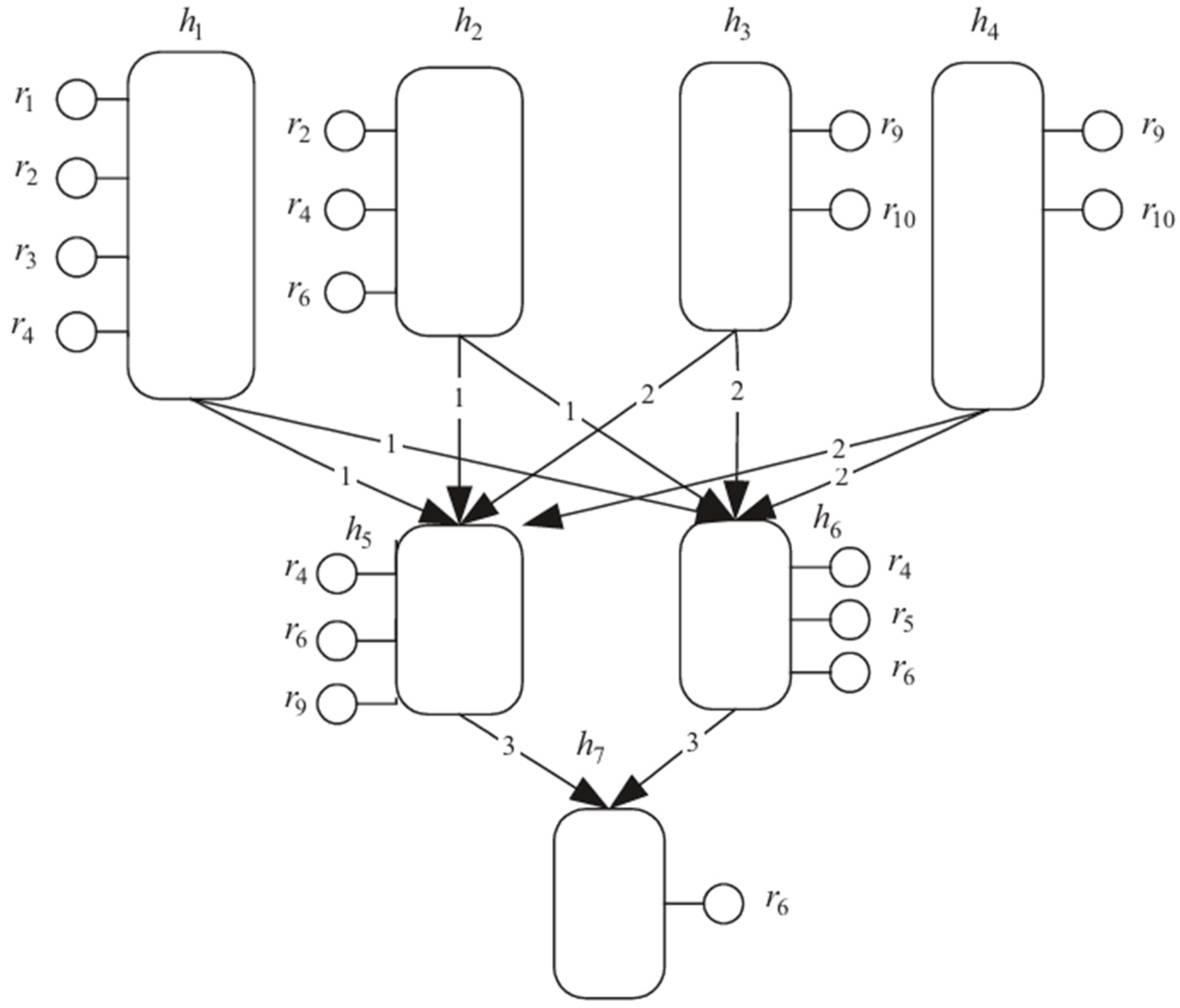

20] defined a holarchy formation problem to lay a foundation to propose models and develop collaborative algorithms to guide the holons to form a holarchy that coherently moves toward the desired goal state with minimal costs.

Figure 2 illustrates a scenario in which a production process is to be formed in HMS with seven product holons

h1,

h2, …,

h7 and ten resource holons

r1,

r2, …,

r10 to accomplish a task with timing constraints. Holonic processes are production processes dynamically created based on the collaboration of product holons. Each product holon has an internal process flow. Execution of the internal process of a product holon may rely on the outputs from the internal processes of one or more upstream product holons. For example, product holon

h5 and

h6 depend on either

h1 or

h2 to provide the type-one parts and depend on either

h3 or

h4 to provide the type-two parts. Product holon

h7 depends on either

h5 or

h6 to provide the type-three parts [

20].

A holonic system is composed of autonomous, independently operating controllers, so-called holons, operating in real time and physically connected to other controlled systems. The entire production process (e.g., a production line) is controlled by such small, distributed units, ideally without a central control unit [

21,

22]. Each holon has only a certain part of the global information about the structure, capabilities, and goals of the production system. This is sufficient for independent functioning and for effective cooperation through the exchange of messages [

23].

Holons handle the necessary regulatory processes locally and independently; only in critical situations (e.g., when the production equipment is overloaded) do they inform other holons about the situation by sending messages. This initiates the activity of the holons, which leads to a change in the situation (to prevent partial failures, or, for example, to reconfigure the production system) [

24].

The holonic approach is much more flexible than the classical approach in terms of the broader range of tools used for control, design, and management of manufacturing systems as well as entire enterprises [

25]. They are robust, fault-tolerant, easily configurable, etc.

The very design features that give holonic systems their flexibility—distribution and independence—also create difficult problems in dealing with complexity, coordination, and resource management, especially as systems become bigger. A key weakness of holonic and multi-agent systems (MAS) data gathering methods is that complexity grows very rapidly as the number of agents increases.

As MAS architectures grow, communication demands increase dramatically. This fast increase in communication and information management is called Coordination Overhead Saturation. This overhead can outweigh the advantages of parallel processing. Unless the task is extremely large, so that parallelization gives significant benefits (like processing millions of items), the difficulty of coordinating multiple agents makes the holonic system “slower, more expensive, and harder to maintain” than a single-agent system.

The complexity of large architectures leads to unexpected behaviors. Medium-sized systems (10 to 100 agents) show some limited unexpected behaviors, but very large holonic systems need complex coordination methods and show significant, often unpredictable, emergent properties. Managing these unpredictable results makes data processing harder and requires a structured organization to bring order back to the system. The system is designed for distributed intelligence, but the rapidly increasing cost of managing the complexity associated with independence limits its practical use on a large scale.

The main benefit of a holon is its ability to operate independently, including handling its own data gathering, prediction, and control locally. However, this conflicts with the limited physical capabilities of devices in an industrial setting.

Industrial CPS designs typically result in physical devices with limited memory and processing power. These constraints mean that the units are designed to efficiently monitor and control physical processes. If external, high-demand data analysis tasks—such as advanced deep learning algorithms needed for real-time problem detection (AD)—are decentralized and performed within the CPS, they interfere with the unit’s main job.

This resource limitation weakens the idea of a completely independent holon capable of advanced self-analysis. To overcome this limitation, architectures often use external, removable processing units for demanding computational tasks during setup and retraining. While this decentralizes the AD execution to meet communication limitations, the reliance on external computational resources adds complexity back into the system, partly reducing the self-sufficiency of the holon. The system’s scalability is limited not only by network capacity but also by the physical resource limitations of the devices they control.

A thorough examination of the weaknesses exposes three key related design problems that hinder the broad and reliable use of holonic and multi-agent systems (HSDA) in industrial settings.

The Problem of Meaningful Information Exchange: Present designs struggle to provide effective, selective, and context-aware information transfer. We have not overcome the problem of sharing excessive information (resulting in high costs) or insufficient information (leading to inaccuracies). This necessitates methods that incorporate data meaning and importance directly into the communication design to ensure accuracy without compromising real-time speed.

The Problem of Design Verification: There is a strong demand for a universal, field-independent approach that can thoroughly verify the basic design quality of a holonic structure. Previous research focuses too heavily on assessing the performance of particular holon examples or procedures.

The Problem of Harmonizing Agreement and Diversity: Current approaches cannot consistently balance the independent nature of data production (which leads to semantic diversity and conflicting local state changes) with the essential system need for a consistent and dependable global system state. This contradiction requires a structured method for controlling shared, changeable data across independent units.

The study reveals that the main weaknesses of current Holonic System Data Acquisition (HSDA) approaches are found in their design and underlying principles, not just in their technical capabilities. Although moving away from centralized systems improved latency and flexibility, it created significant new difficulties regarding system size, coordination complexity, differences in data meaning, and maintaining consistent data. The core problems arise from the Contextual Communication Deficit (the difficulty of efficiently and selectively sharing relevant data knowledge) and the Architectural Validation Deficit (the absence of universal methods to assess the structural integrity of the holarchy).

The continued presence of these problems, supported by industry findings and the limitations of current research, requires a different strategy. The suggested Universal, Meta-Validation Methodology (GPM-VM) offers a clearly innovative position by fundamentally changing the research focus from improving performance within a particular holonic setup to evaluating the structural soundness of the architectural model itself. This strategy offers a strong, scalable base that is crucial for the industrial implementation of future holonic manufacturing and Cyber-Physical Production System (CPPS) environments. The comparison of centralized and decentralized holonic data acquisition paradigms is shown in

Table 1.

The move towards holonic systems involves a core compromise: giving up the dependable, straightforward data management of centralized systems in exchange for the independent operation and adaptability of distributed structures. Centralized systems provide uniform data and easier oversight, but they struggle to effectively handle the fast-paced, changing, and geographically spread-out demands of today’s industry. Holonic structures are specifically built to handle these dynamic situations, but this introduces significant new difficulties related to collaboration and ensuring data is consistent across the system. These challenges are now a primary focus in data gathering research.

Having pinpointed deficiencies in existing models and research, it is clear that a holonic approach is required for redesigning manufacturing systems. This approach should address the shortcomings of current methodologies and offer improvements toward including sustainability, multi-level perspectives, and multi-scale considerations, all in line with the goals of the 2030 Agenda and enabled by digitalization. This suggested holonic structure leverages Industry 4.0 principles through the integration of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), positioning the holonic manufacturing system (HMS) as a key organizational element. The HMS is intended to manage the increasing intricacy of contemporary manufacturing systems and to integrate and capitalize on the advantages provided by digital and technological facilitators, ultimately suggesting a path for redesigning sustainable and intelligent manufacturing [

26].

4. Proposed System Architecture and Design

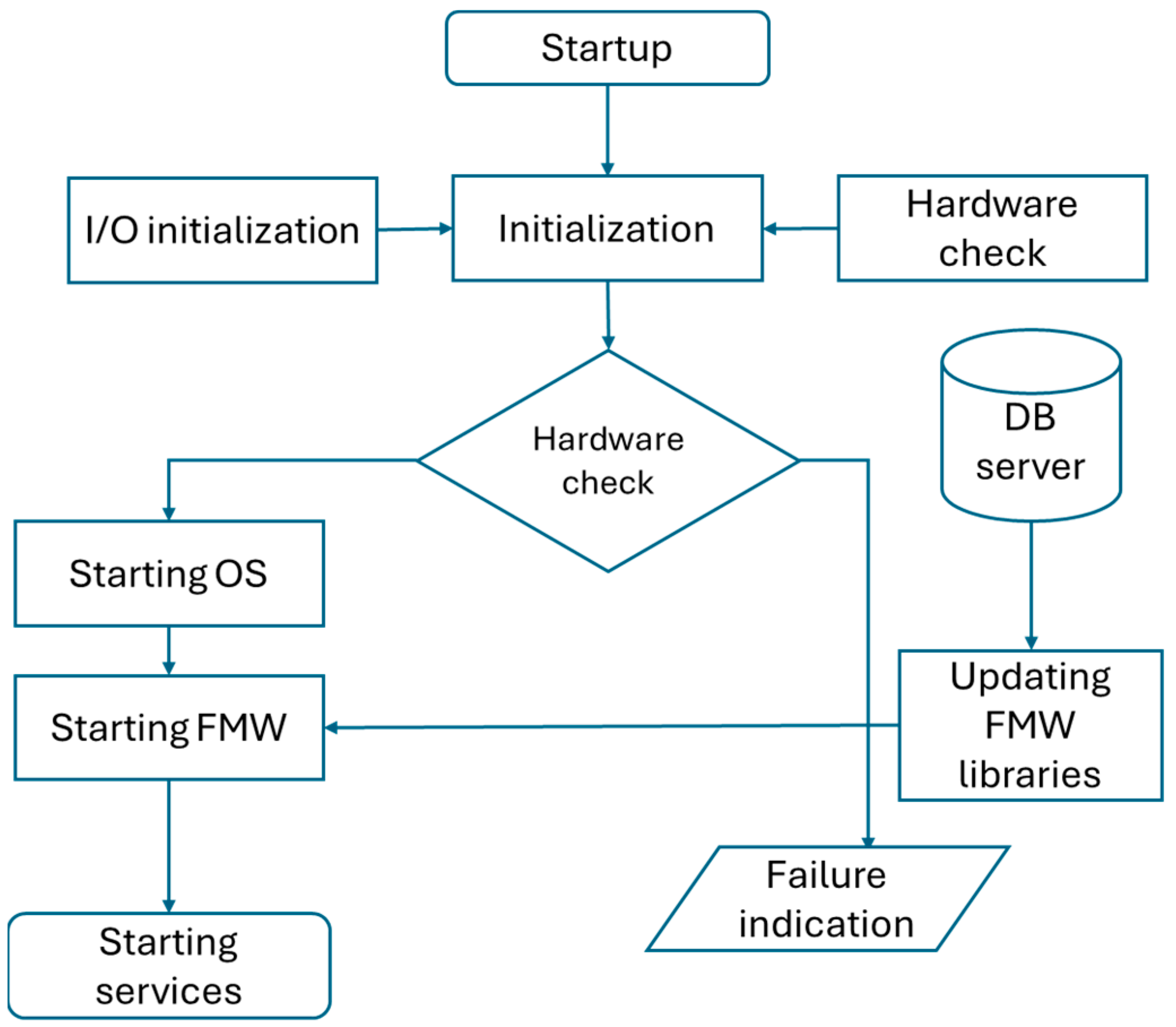

Based on a comprehensive analysis of the principle of operation of data collection systems and the definition of scientific problems in the subject area, an algorithm was designed (

Figure 3). The algorithm represents a methodological sequence of steps that must be performed when designing the introduction of holonic control into an existing or new production system. Areas related to the design of a holon ensuring interaction between elements of the production system will be defined in subsequent subsections, which will clarify the requirements for technical and software equipment necessary to meet the main goal.

The methodology for developing and deploying an information system (IS) for a holonic production system is divided into four main phases: initial analysis, holonic design, implementation, and final review.

Phase 1: Initial analysis and definition—the process begins with the launch and definition of the company’s intent. This is followed by an IS analysis to determine the current status and needs. A key step is the definition of objectives and indicators (KPIs) used to measure the success of the project. Next, the tasks of the IS modules are defined in detail, and the available communication interfaces are analyzed. Based on this analysis, an IS that meets the communication interface requirements is selected. This is followed by the first decision: Does the IS meet the communication interface requirements? If not, the module tasks must be redefined. If so, the process proceeds to the design phase.

Phase 2: Context definition and holonic design—this phase focuses on the specific requirements of the holonic system and is influenced by several external inputs (constraints): defining workflows, defining input/output data for operations, defining technical constraints, financial and economic constraints, and OHS (legislation).

The central question is as follows: Does the information system have holonic control capabilities? If not, it is necessary to revise the definitions of I/O data and limitations. If so, proceed with the design of a decentralized architecture:

Holonic interaction design (see

Section 4.3): Determine the rules and protocols for how individual autonomous holons will communicate with each other.

Design of data structure and communication interface: Specification of data formats and communication specifications.

Design of technical interface means for a unified platform (see

Section 4.4): Design of adapters and APIs to connect different technologies.

Defining the role of holons in the holarchy: Determining the hierarchy and competencies of each holon in the system. This phase creates a data collection methodology that forms the basis for a decentralized holonic system.

Phase 3: Implementation and verification—the design is followed by the physical implementation of the system: processing the communication IS architecture: Building and coding the designed architecture. Parameterization of HW and SW modules: Setting operating parameters for hardware and software components. Phase of verifying the correct functionality of the IS: Performing initial tests to ensure technical correctness.

Phase 4: Performance review and operation — the final phase involves a critical assessment of the entire project. The main decision revolves around the question: Have the defined objectives been met and is the correct operation of the holonic production system ensured? If not, corrective measures must be implemented, and the cycle returns to the verification phase.

Information systems for supporting efficient and flexible production have their defined position and tasks within the vertical integration of information systems. The systems necessary for the holonic production system and their software will be the subject of the chapter. In the chapter, there is the identification and design of the necessary modules and their functionality. This functionality forms the condition that is set for the fulfillment of information systems for the holonic production system.

The methodology for developing and deploying an information system (IS) for a holonic production system is divided into four main phases: initial analysis, holonic design, implementation, and final verification.

If not, corrective measures must be implemented, and the cycle returns to the IS functionality verification phase. If so, the system transitions to normal operation of the holonic production system, and the process concludes with the end phase. This methodology ensures that the IS is not only technically functional, but also in line with the company’s strategic goals and the specific requirements of decentralized holonic management.

The following subchapters present the operating principle and structure of enterprise information systems in the context of mutual integration possibilities with respect to the holonic management approach.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed holonic methodology and its resulting system, the following key metrics are proposed, which measure performance, resilience, and integration costs:

Data Throughput: Measures the volume of data (in MB/s or messages/s) processed between holons or between holons and the central platform.

Latency: Measures the response time (in ms) between sending requests (e.g., from a control holon) and receiving responses (e.g., from a production holon).

Holon Configuration Time: The time (in min/h) required to connect and fully configure a new holon or reconfigure an existing one.

Reconfiguration Time After Failure: Time (in seconds or milliseconds) required to detect the failure of a single holon and take over its function or redirect the tasks of the remaining holarchy.

Adaptability Index: Number of changes in the production plan/process that the system can handle without manual reprogramming (e.g., number of successful re-plannings per change).

Reduction in Integration Effort: Comparison of the time/cost of integrating a new device into the HVS versus a traditional (central) system (measured as % engineering time savings).

Equipment Utilization: % of time that the device is in operation (affected by reconfiguration and resilience).

The holonic approach is proposed in the methodology, bringing advantages mainly due to its decentralized control logic and holon autonomy.

If one of the sensor modules (holons) in the system for simulating virtual redundant sensors (as mentioned in the literature) were to fail, the central system would have to perform a production, and the operator would manually reconfigure the control logic. The holonic system (according to the Reconfiguration Time metric) detected and responded within 5 s by having the remaining redundant holons autonomously agree to take over, ensuring continuous operation.

4.1. MESs

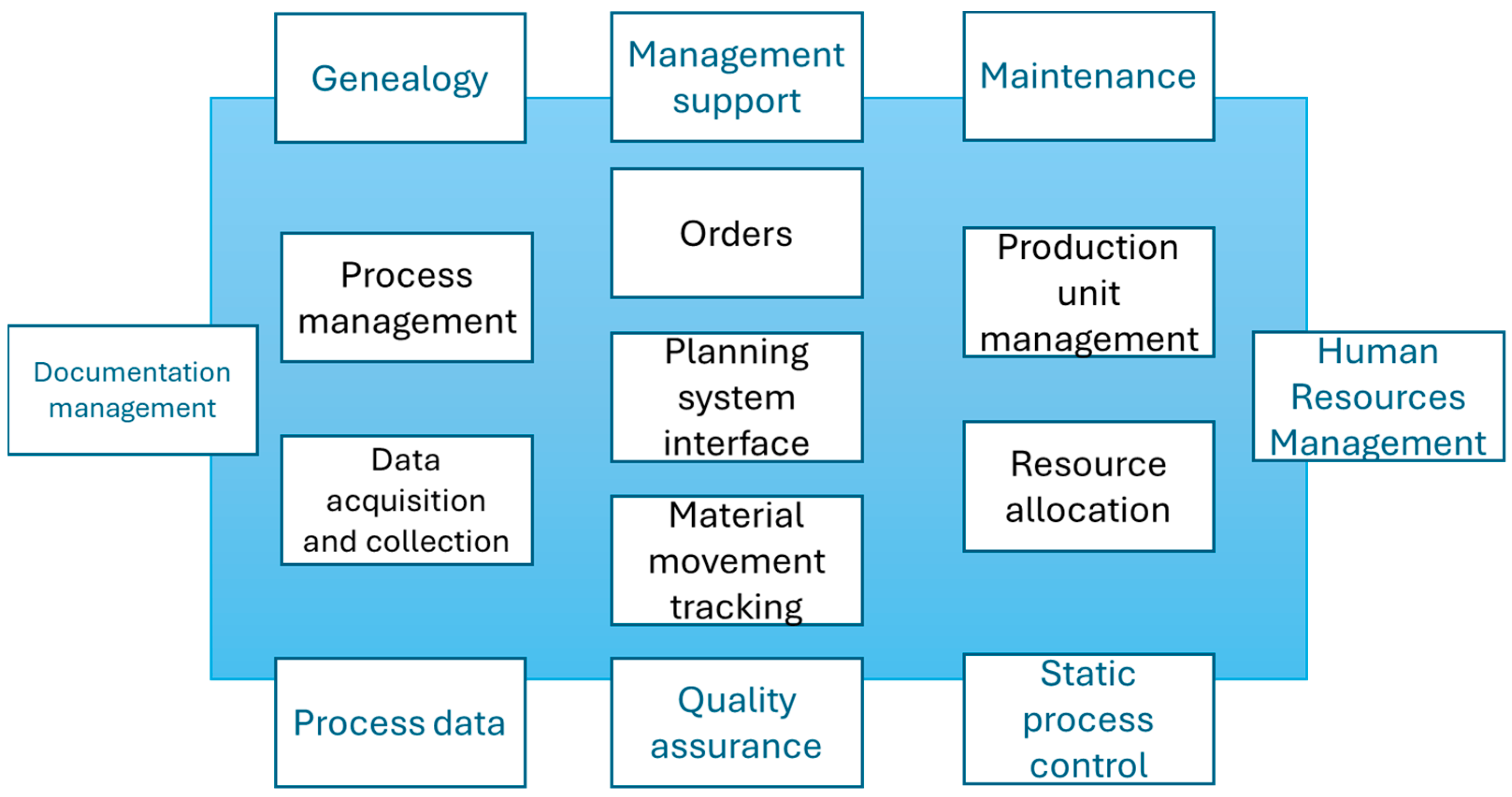

MESs are primarily developed for operational planning and production management, and their purpose is to provide operational information for immediate management and optimization of production processes. MESs help production managers to better use information for launching or optimizing the production plan. They are also suitable for deployment in production, where a functional ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) enterprise system is already deployed to streamline the management and optimization of the company’s production processes. It is, therefore, a directly integrated computer system that accumulates methods and tools necessary for improving and optimizing production.

While the traditional MESA International MES functional model has historically provided a relevant conceptual framework, the system’s functional scope is now mapped and aligned with the international standard IEC 62264 (ISA-95) [

31]. This standard provides a clearer, universally recognized framework for defining the hierarchical relationships and activity domains of the manufacturing execution system, ensuring our proposed integration layer meets current industrial and academic best practices for information exchange between enterprise and production levels.

Unlike classic information systems, they work with current data in real time, which allows them to flexibly respond to both non-standard conditions in production and immediate business requirements and to adapt the production process to be as efficient as possible. Regarding enterprise groups of systems, MESs act simultaneously as a source and a recipient of information. Production information systems are an effective tool for monitoring, managing, and evaluating the production process in all its complexity. They were developed to fill the communication gaps between the production planning system (MRP—Material requirements planning) and the MCS (Manufacturing Control Systems) used to run the equipment on the production platform.

MES functionality covers a wide range of features that a system can contain. These manufacturing information systems generally implement functional areas according to the requirements of the MESA (

Figure 4). Several functions may overlap when implementing the system in specific conditions, and conversely, some functions may not be included in the final version at all. The resulting solution always depends on the needs and requirements of the customer. The MESA (the manufacturing execution systems Association), therefore, conducted a study on users and offered the following list of benefits of using a computer-controlled manufacturing information system:

Reduction in production cycle time, reduction in time required for implementation;

Reduction or elimination of input data processing time;

Reduction in work in process [

32];

Reduction or elimination of administrative work;

Improvement of product quality;

Strengthening the growth of operating technicians;

Improvement of process planning;

Improvement of customer service [

33].

There is chosen a description based on the MESA-11 model because our initial focus was on providing an overview of the historical development and basic functions of MESs, and the MESA-11 model provides an excellent didactic framework for presenting the 11 key functions that became the basis for later, more complex standards such as ISA-95. The MESA-11 model offers a very clean and clear division of functional areas.

Although ISA-95 provides a more robust model for the integration and enterprise levels, MESA-11 is often clearer for an initial understanding of the basic scope of MESs. ISA-95/IEC 62264 is the current standard for modern MES architectures. The MESA-11 model is used as a historical and didactic basis for introducing the basic functional areas that are incorporated into the ISA-95 standard. Within modern manufacturing execution systems (MESs), it is strongly emphasized that the ISA-95/IEC 62264 standard is key to current architectural solutions.

The historical MESA-11 model serves as a didactic basis for understanding the basic functional areas that are fully integrated and structured in the ISA-95 standard. ISA-95 defines models and terminology for vertical integration—connecting enterprise systems (ERP, Level 4) with production and control systems (Level 3 and below). While MESA-11 defined what MES should do (with 11 basic functions), ISA-95 specifies how these functions should be integrated. In Part 3 (Manufacturing Control Activities Model), ISA-95 restructures the MESA-11 functions into four main management areas (Manufacturing Operations Management, Quality Operations Management, Maintenance Operations Management, and Performance Analysis) and adds a fifth area, Inventory Operations Management. This approach ensures that the description of functional areas is fully consistent with modern industry standards.

The goal is, therefore, to show that MESA-11 serves as an educational introduction, but modern practice and data interoperability requirements are fully governed by the comprehensive ISA-95 framework.

ISA-95 includes a summary of the scope of the manufacturing operations and control domain; a discussion of how physical assets of a manufacturing enterprise are organized; a list of the functions associated with the interface between control functions and enterprise functions; and a description of the information shared between control functions and enterprise functions (ISA-95 Standard, 2025). The comparison of centralized and decentralized is shown in

Table 2.

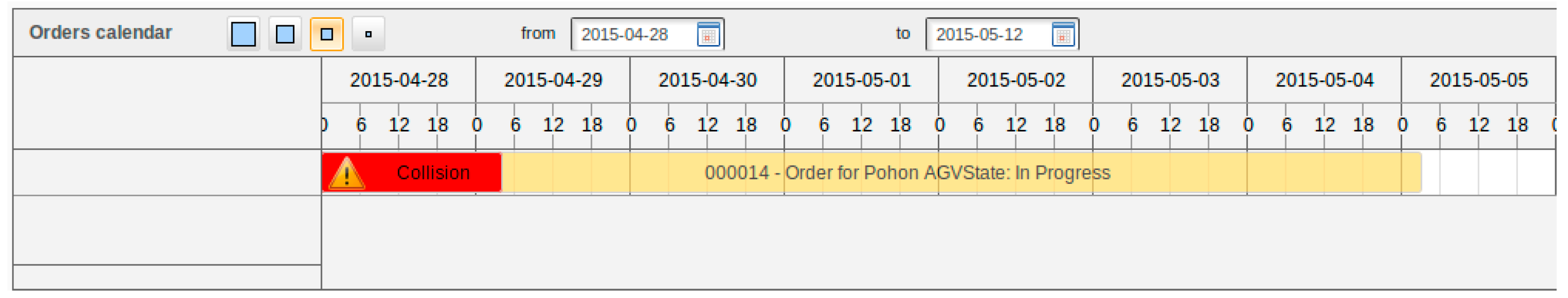

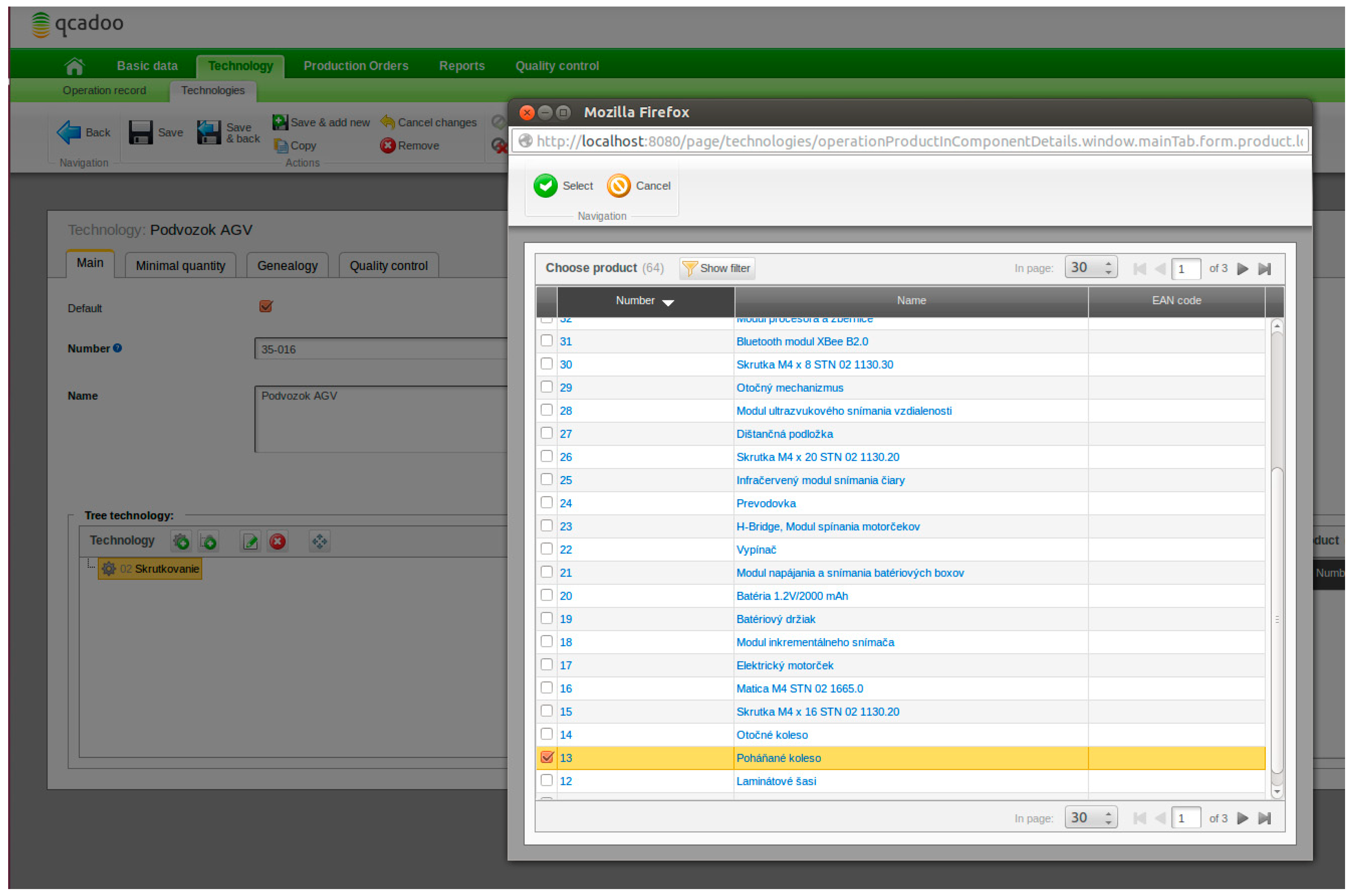

Visualization of technology statuses serves as an immediate overview of the operating status (

Figure 5) of individual machines, production lines, and equipment. It includes information on operating conditions in production, technological parameters affecting production quality, data related to products (machine cycles, numbers of pieces), and records of downtimes or equipment shutdowns during machine setup. This allows the creation of short-term (e.g., daily) production schedules considering the sequences of production operations and their distribution between individual production equipment.

Resource allocation ensures that all necessary production resources (machines, tools, labor, materials, energy, etc.) are available for the start of production (in the correct time–place–quality configuration).

Resource allocation includes the allocation of production units according to assigned work orders and schedules, coordination of production between lines, ensuring the necessary number of raw materials and energy, and monitoring the status of the production cycle.

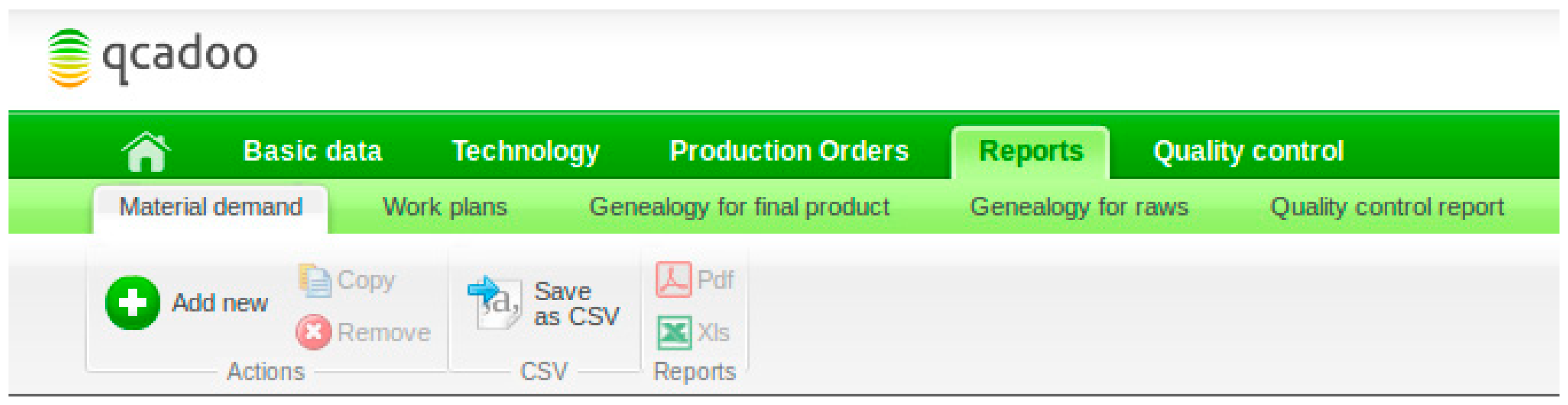

Documentation management is a program module for managing all records and documents (schemes, production procedures, schedules, change protocols, procedures, work orders, etc.), information on the progress and results of production, comparison of the assignment with reality, and sending instructions to the equipment operator, while at the same time providing procedures for control systems. Log export options in the MES Qcadoo environment are shown in

Figure 6.

Tracking each product, batch, or series throughout the entire production cycle and preserving the actual conditions under which they were produced (records of individual production steps, materials used, procedures, the course of key technological variables, etc.). Performance analysis monitors and calculates key production indicators, compares the results currently achieved in production with their short-term history, and estimates economic outputs. This functionality can also be processed by an ERP system that has advanced performance analysis. Human resources management keeps records and provides information about personnel qualifications (education, certificates, special knowledge, and skills). It tracks indirect activities in the preparation of materials, machines, and tools as a basis for calculating costs based on activity (e.g., how much time someone spends solving a downtime, changing a machine).

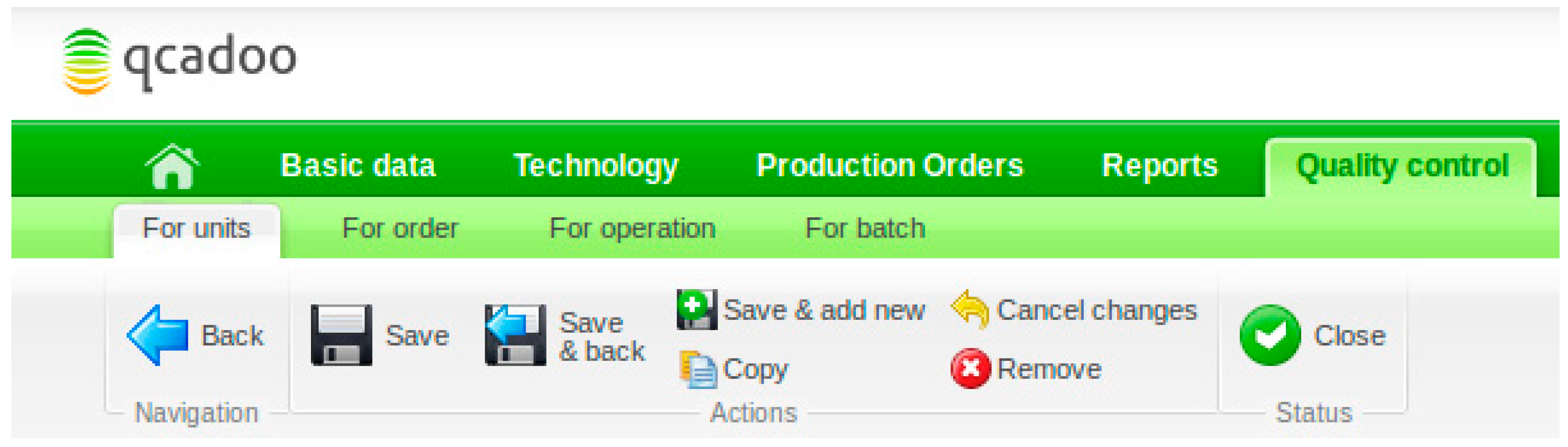

The functional area of maintenance planning and management monitors and manages activities carried out with the aim of maintaining production assets in such a technical condition as to prevent unplanned production interruptions. It provides periodic preventive maintenance schedules and allows you to manage maintenance according to the actual condition of the equipment. Control of the production process is provided by operator functions. This functionality can only be provided in the case of connecting the technology control system with a specific module that allows sending commands that can be processed by the control system. Quality management ensures real-time analysis of data captured from the production equipment to monitor the quality of the manufactured product and identify unwanted deviations in a timely manner. It uses SPC/SQC methods of continuous statistical search to find the differences between the required “ideal” and actual process parameters and to search for the causes of these differences. Quality management (

Figure 7) also often includes off-line analyses of the information system.

Data collection and archiving are the basic building blocks of every MES system. They ensure the continuous collection of production data in real time, long-term archiving, and availability for further processing. An integral part is data protection against loss and misuse. An MES thus ensures the implementation of individual functions:

Operational planning and optimization of production series;

Process control and electronic production recording;

Technological data collection and archiving;

Data analysis, balancing, and creating protocols;

Production monitoring and production operation history;

Tracking of materials in production and operational inventory.

There is a constant exchange of information between the MES level and the higher and lower levels during system operation. The problem with the exchange of information between system levels is caused by the following:

Different levels of abstraction, work procedures (

Figure 8), documents, control and signals;

Different processing periods (MESs operate in real time, and the period is in milliseconds);

Different data structures (different types of documents, design drawings, and other records in databases);

Different levels of accuracy (measured quantities, control signals, forecasts, plans, and estimates);

Different processing approaches (managers, production workers, machines, and equipment).

4.2. Design of Interaction Holon

The MES system modules, according to the MESA, can be divided into main (blue) and support functions (black), as shown in

Figure 9.

The proposed holon architecture respects the FIPA CNIP. To implement the holon, it is necessary to choose the appropriate software and hardware. There is a proposed basic algorithm of the holon, which can work in combination with the input/output circuits of the system to ensure communication via the industrial bus of the control system, or data transfer from the sensor (

Figure 10). The proposal is focused on universality. The holon can also work at the level of the operating system of the controlled device. This means that the software, the control program, and the communication interface are identical. The holon can be implemented at the following level:

Sensor;

PLC;

Information system.

The following subsection will deal with the design of means that meet the condition of compatibility with the identified levels.

Figure 10 illustrates the startup process of an interaction holon, emphasizing the critical role of the Hardware Health Check (HHC) phase. The startup flow begins with the System Boot. The process immediately proceeds with the hardware check. This check is a crucial decision node that determines the holon’s subsequent action.

Successful Check (Path A—Standard Startup): If the hardware check is successful (e.g., all sensors connected, CPU stable, and memory clear), the holon continues with the standard startup sequence. This involves loading the essential software components: the Operating System (OS), the middleware (FMW), and activating the Holon Services (e.g., REST API endpoints and data acquisition loops). Once services are initialized, the holon enters the Operational state.

Failed Check (Path B—Adaptive Fault Handling): If the hardware check fails, the holon immediately enters an adaptive state. Instead of failing outright, the holon first Indicates the Failure (communicating its status to the Holarchy Manager). Following this, it initiates the Middleware Update Process. This update procedure is a self-healing attempt, allowing the holon to potentially restore corrupted libraries or configurations before fully rebooting. The holon then attempts a reboot to load the newly updated components.

This procedure highlights the holon’s ability to perform self-healing or adaptive actions before a hard failure, demonstrating partial autonomy. The interaction holon is thus designed as an intelligent unit capable of localized recovery in the event of hardware or software integrity failures, ensuring the stability and continuous operation of the distributed system.

4.3. Design of Technical Interface Means for a Unified Platform

The selection of the Python 3.14 programming language was based on its unparalleled suitability for rapid prototyping, cross-platform compatibility, and extensive library ecosystem, which are critical features for flexible, decentralized holonic agents. This choice allows for significantly faster development and easier code maintenance compared to lower-level languages, simplifying the collaborative development process. Furthermore, the Bottle micro-framework was chosen over full-stack alternatives (such as Django) due to its minimal footprint. Distributed as a single-file module with zero external dependencies outside the Python Standard Library, Bottle ensures extremely low overhead and high resource efficiency. This minimal design is vital when deploying RESTful API services on resource-constrained edge devices, reducing deployment complexity and improving startup time compared to more feature-heavy alternatives.

The Raspberry Pi 4 Model B was selected to embody the low-cost edge computing paradigm. To ensure the necessary industrial adaptability and stability demanded by the manufacturing environment, we implemented several key hardware and software measures. Low-level, hard real-time control remains delegated to traditional PLCs or dedicated microcontrollers, while the Raspberry Pi focuses exclusively on supervisory data collection, communication, and decision-making at the information layer. Stability is enhanced by housing the device in an industrial enclosure and powering it with an isolated industrial-grade 24 V DC power supply (with a step-down converter). This configuration offers robust protection against common power issues like spikes and electromagnetic interference (EMI). Additionally, the system utilizes a read-only root file system configuration to prevent data corruption in the event of sudden power loss, ensuring reliable long-term operation.

The selection of this specific technical stack was driven by the project’s requirements for rapid prototyping and resource efficiency on a constrained edge platform. Python was chosen for its high-level abstraction, accelerating the development cycle. The Bottle.py micro-framework was intentionally selected for its minimal footprint and low resource overhead, making it highly efficient for deployment on the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B. Similarly, the initial choice of the REST protocol for communication prioritized its simplicity, ease of debugging, and standard HTTP compatibility, simplifying integration testing in the prototype phase.

The current synchronous RESTful HTTP architecture, while simple for the prototype, is acknowledged to have limitations in terms of scalability for large-scale industrial deployment, potentially leading to bottlenecks at the central Web Service Communication Interface (WSCI). To achieve high-throughput, horizontally scalable, and decoupled communication suitable for an industrial-grade holarchy, we propose that future implementations migrate to an Asynchronous Message Broker architecture, such as one utilizing MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport). MQTT’s lightweight, publish/subscribe model is inherently more suitable for managing the state changes and events within a large, distributed Industrial IoT system.

A critical industrial requirement is security, which the current basic HTTP implementation lacks. A production-ready system must integrate standard security measures. This includes Transport Layer Security (TLS/SSL) to encrypt all communication between holons and the WSCI, and a robust token-based authentication and authorization mechanism to secure access to data and resources across the holarchy.

To ensure the cooperation of holons, the correct choice of the architecture of mutual communication is essential. The most common way of implementing software communication identified during this research appeared in the literature and from Internet resources, the SOA architecture, which is also often implemented. The abbreviation SOA comes from the English phrase Service-Oriented Architecture, and in recent years has become a synonym for a new concept of connecting business needs with the possibilities of current information technologies in the enterprise. It represents a concept whose creation was required by the rapid development of IT and information systems in the 1990s, as well as the solution of related problems in the transfer and processing of information in heterogeneous systems. The SOA concept (

Figure 11) provides a guide to solving integration problems either within a single enterprise or between several enterprises. The core is the use of services in processing requests for information exchange between heterogeneous systems. At the same time, the concept of service in IT terminology can be understood in the same way as this concept is understood in everyday life (order, etc.). In a narrower sense, a service should be understood as a suitable application (component) that meets the following requirements in particular:

Clear localizability in a certain environment (e.g., on the Internet or in a certain organizational unit) [

34].

Support for globally accepted standards (XML, SOAP, JMS, JCA, etc.), which ensures the usability of the service without the need to develop and use proprietary communication protocols.

Autonomy—no additional software needs to be installed to use the service.

Self-description—information is also available at the location where the service is localized regarding the functionality the service provides and under what conditions this functionality can be used.

In SOA implementations, there are cases where meeting communication requirements is unnecessarily complicated and time-consuming—for example, obtaining additional status information and information about additional resources. We, therefore, propose using the REST architecture as a replacement for the SOA architecture for holons whose communication layer is formed by separate holons, such as in the form of a PC.

REST (Representational State Transfer) is a way to easily create, read, edit, or delete information from a server-holon using simple HTTP calls. REST represents an interface architecture designed for distributed environments. REST was designed and described in 2000 by Roy Fielding (co-author of the HTTP protocol) as part of his dissertation Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures. In the context of the work, the most interesting information is in chapter 5, in which Fielding derives the principles of REST based on known approaches to architecture. The REST interface can be used for uniform and simple access to resources. The resource can be data, as well as application states (if they can be described by specific data). REST is, therefore, unlike the better-known XML-RPC or SOAP, as it is data-oriented, not procedural.

The biggest difference between SOAP and REST is, therefore, mainly in how you communicate with the server—what standards and how they use them. On the contrary, the method that will serve this request on the server is written in a different programming language and can be very similar in both cases. A REST framework is needed that will call the correct method based on the URL. An interesting feature of REST is that in the response that comes from the server, references to other data can be written/represented by URLs. In this way, further data can be obtained based on the first response. This is undoubtedly a feature that is difficult to achieve in SOAP services, and it is also a step back to the classic web, where hyperlinking was a common thing.

Basic principles of REST communication architecture—the state of the application and its behavior is expressed by the so-called RESOURCE (key resource), where each resource holon must have a unique identifier (URL). HATEOAS (hyper-medial as the Engine of Application State) represents the state of the application and is specified by the URL. Other possible states can be obtained using links that the client receives in response from the server. A unified approach is defined for obtaining and manipulating resources in the form of four CRUD operations (create, read, update, and delete). Resources can be represented (XML, HTML, JSON, SVG, and PDF), and the client does not work directly with the resource, but with its representation [

35].

4.3.1. Communication Protocol

The design of the holonic information system is centered on the autonomous data management within each production holon (PH). This process is executed using a unified, lightweight REST communication protocol. This protocol is not only a network standard but also a template for defining the data structures and message formats used by all holons, thereby resolving potential issues arising from the diversity of decentralized information sources.

The protocol defines a rigorous, procedural methodology for data exchange. This methodology establishes the precise sequence of operations each PH executes to acquire, process, and publish manufacturing data, ensuring system-wide semantic consistency.

The data management process commences with Configuration Loading. Each holon loads a definition file that dictates two critical parameters: the low-level memory addresses (e.g., Modbus registers or OPC-UA tags) of the physical control system (PLC) it monitors, and the specific sampling rate required for each defined data point. This configuration forms the foundation for the subsequent data acquisition and publication cycle, which is detailed in the following sections.

Python was chosen for its cross-platform compatibility and extensive industrial library support (e.g., Modbus, OPC UA). The Bottle micro-framework was selected for its minimal footprint and low resource overhead, enabling efficient deployment of RESTful API services on constrained edge devices:

Client/Server—used to define responsibility.

Stateless—each request must contain all the information necessary to execute it.

CACHE—each request can be explicitly marked as cacheable or non-cacheable, which allows the ability to transparently increase performance by adding a cache between the client and the server. Code-On-Demand—client functionality can be extended by code sent by the server (for example, JavaScript).

Layering—allows the stacking of layers providing services to increase variability (cache, transformation, load balancing, etc.) [

36].

There are, of course, other approaches to solving distributed architectures, such as RPC (Remote Procedure Call). In general, the difference between REST and RPC can be described on two levels:

Semantics of operations and what is distributed;

Semantics of operations in REST are final and consist only of CRUD (create, read, update, and delete) on a given resource holon.

In contrast, the semantic structure of RPC corresponds to the methods that are called. In REST, the state (data represented by a resource) is distributed, as opposed to the message that is distributed in RPC.

REST architecture represents services that are about a smaller number of standards and their more efficient use. The basic standards are HTTP, URI, and XML (or JSON, or XHTML, etc.). Knowledge of the above is a basic prerequisite and a necessary condition for using and communicating with REST services. The basic idea is that the URI defines the data you want to work with and the HTTP operation, i.e., what we want to do with the data. So far, we have encountered two operations: GET and POST. The set of these operations allows us to design a holonic structure for managing other holons. When designing the concept, the Python language was chosen because of its multi-platform nature.

4.3.2. Python Programming Language Design

Python is a multi-paradigm language similar to Perl. Python supports object-oriented, structured, and functional programming. It is a dynamically typed language, supporting many high-level data structures. Although Python is often referred to as a “scripting language”, it is used to develop many large software projects, such as the Zope application server and the Mnet and Bit-Torrent file-sharing systems. It is also widely used by Google. Python proponents prefer to call it a high-level dynamic programming language, because the term “scripting language” is associated with languages that are used only for simple shell scripts, or with languages like JavaScript: simpler and, for most purposes, less capable than “real” programming languages like Python [

37].

Another important feature of Python is that it is easy to extend. New built-in modules can be easily written in C or C++. Python can also be used as an extension language for existing modules and applications that need a programmable interface. Supported operating systems include the following:

Linux;

BSD;

Mac OS X;

Windows.

The support of the operating systems was key in choosing the Python language. Industrial computers support the Windows operating system in most cases. On the other hand, information systems are largely run on servers built on the Linux operating system for reasons of stability and security.

4.3.3. Program Module Ensuring Interaction

To meet the requirement of holon communication on a unified data layer, there is an extension for the Python language. This extension ensures communication of the holon control program with the control programs of other holons in the holarchy through the REST architecture. The REST architecture can be implemented by its own extension or by using existing ones. From the perspective of the sophistication of the existing ones, the development of their own architecture is inefficient. The source code is accessible and, therefore, possible extensions or modifications are feasible [

38].

Bottle is a fast, simple, and lightweight WSGI micro web-framework for Python. It is distributed as a module in a single file and does not use any other libraries than standard Python libraries [

39].

Key features that were considered in the selection include the following:

Routing: Requests for prompt execution of a function through mapping with support for clean and dynamic URL addresses.

Templates: Fast and built-in core template system with support for other Python extensions such as mako, jinja2, and Gepard.

Transactions: Convenient access to choosing the form of input or output data, adding files, cookies, headers, and other metadata for HTTP purposes.

Server: Built-in HTTP server with support for modules fapws3, Bjoern, Gae, CherryPy, or any others compatible with the ability to work with a WSGI HTTP server. Example of Python syntax and use of the Bottle module when loading data from the information system database.

The proposed architecture can also be used for devices designed for the Internet of Things.

4.3.4. Design of the Technical Equipment of the Interaction Holon

When choosing the technical equipment and implementing the interaction holon, it is important to pay attention to the support of the software that was defined in the previous chapter. When the interaction holon cooperates in the case of connection with industrial automation control systems, it is necessary to consider the number of types of communication interfaces and their durability in the industry.

During experimental verification, a Raspberry PI computer was used. Specifications of the proposed experimental holon interaction are as follows:

900 MHz quad-core ARM Cortex-A7 CPU;

1 GB RAM;

4 USB ports;

40 GPIO pins;

Full HDMI port;

Ethernet port;

Combined 3.5 mm audio jack and composite video;

Camera Connection Interface (CSI);

Display Interface (DSI);

Micro SD card slot;

3D VideoCore IV graphics core.

Currently, other models from various manufacturers based on the same architecture that allows for the implementation of holonic control and data collection are appearing on the market. There are several modules for the devices, such as communication extensions, input/output modules. In the experiment, the standard hardware configuration of the Raspberry PI was used.

Software architecture design (

Figure 12) of the proposed solution using a computer from the point of view of software. The holon operating system is based on the Linux kernel, which can work with input/output ports (GPIO) that can read a digital or analogue signal.

There is an I2C communication line to which it is possible to connect peripherals that expand the original hardware configuration capabilities of the device. The operating system runs the WSGI service, which is part of the software that was specified and provides REST API communication with other holons in the network.

Internal software architecture of the interaction holon is created by the following:

WSGI, REST API—Communication/Application layer. Ensures external communication with other holons or the control system. Defines entry points for commands (e.g., HTTP POST to execute a task) and provides data (e.g., HTTP GET for sensor status). Interaction: Communicates with the Python layer (executes algorithm functions) and with the external world (Ethernet/Wi-Fi).

Python + Bottle + Algorithm—Control/Decision logic. Forms the core of the holon. Bottle is a minimalist Python web framework that processes HTTP requests from the REST API. Algorithms implement the autonomous logic of the holon (CNP, planning, control). Interaction: Receives commands from the REST API and sends commands directly to the GPIO layer for physical hardware control.

Operating System (Windows, Linux, Mac OS, etc.)—base layer. Provides drivers and an environment for running the Python runtime and accessing hardware (GPIO). Interaction: Serves all higher layers.

GPIO—Physical I/O layer—provides direct access to hardware pins (General Purpose Input/Output) for reading sensors and writing to actuators (motors, relays, and lights). Interaction: Receives commands only from the Python layer and provides status data to it.

The interplay between the General-Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) abstraction, the Representational State Transfer (REST) Application Programming Interface (API) abstraction, and the fundamental Application/Business Logic stratum constitutes a pivotal architectural characteristic of numerous integrated and Internet of Things (IoT) systems. These layers establish a hierarchical structure, enabling the regulation and observation of physical phenomena (through the GPIO abstraction) via a network-accessible interface (the REST API abstraction).

Defining the roles of a holon in a holarchy—mutual interaction is a fundamental property of holonic control. Holons exchange information with each other. Several protocols have been introduced in this area, covering querying, voting, negotiation, and auction execution, and have also been standardized by the FIPA (Foundation for Intelligent Physical Agents) organization. This organization was founded in 1996 with the aim of introducing a whole set of standards that define agent systems and their communication. The established standards include the following:

FIPA Agent Communication Language (ACL), which defines the language in which agents communicate. The structure of the given message and its ontology are defined [

40].

FIPA Contract Net Interaction Protocol (CNIP), which is based on CNP and is one of the most widely used auction protocols [

41].

CNP was designed in 1980. It is a high-level communication protocol for distributed control and cooperation in task execution. Any holon can initiate a negotiation process and contact other holons, requesting that they provide a given operation (or service). This makes it a “manager” or “moderator” that can contact other holons and mediate mutual communication. It can contact the following:

All holons (broadcast).

Selected holons (multicast) [

42].

A unique holon (unicast) [

43].

FIPA CNIP is based on small modifications of CNP, namely the addition of rejection and confirmation communication messages (messages requiring the execution of actions-acts). Holons that accept this request are able to generate responses together. Each initiated conversation (part of communication with a certain goal) is marked with a conversation-id parameter, which is global, non-zero, and assigned to the initiator. Holons that are part of this communication are forced to mark the ACL message with this identifier. This allows the holon to distinguish individual conversations and reflect on them in a state of inactivity.

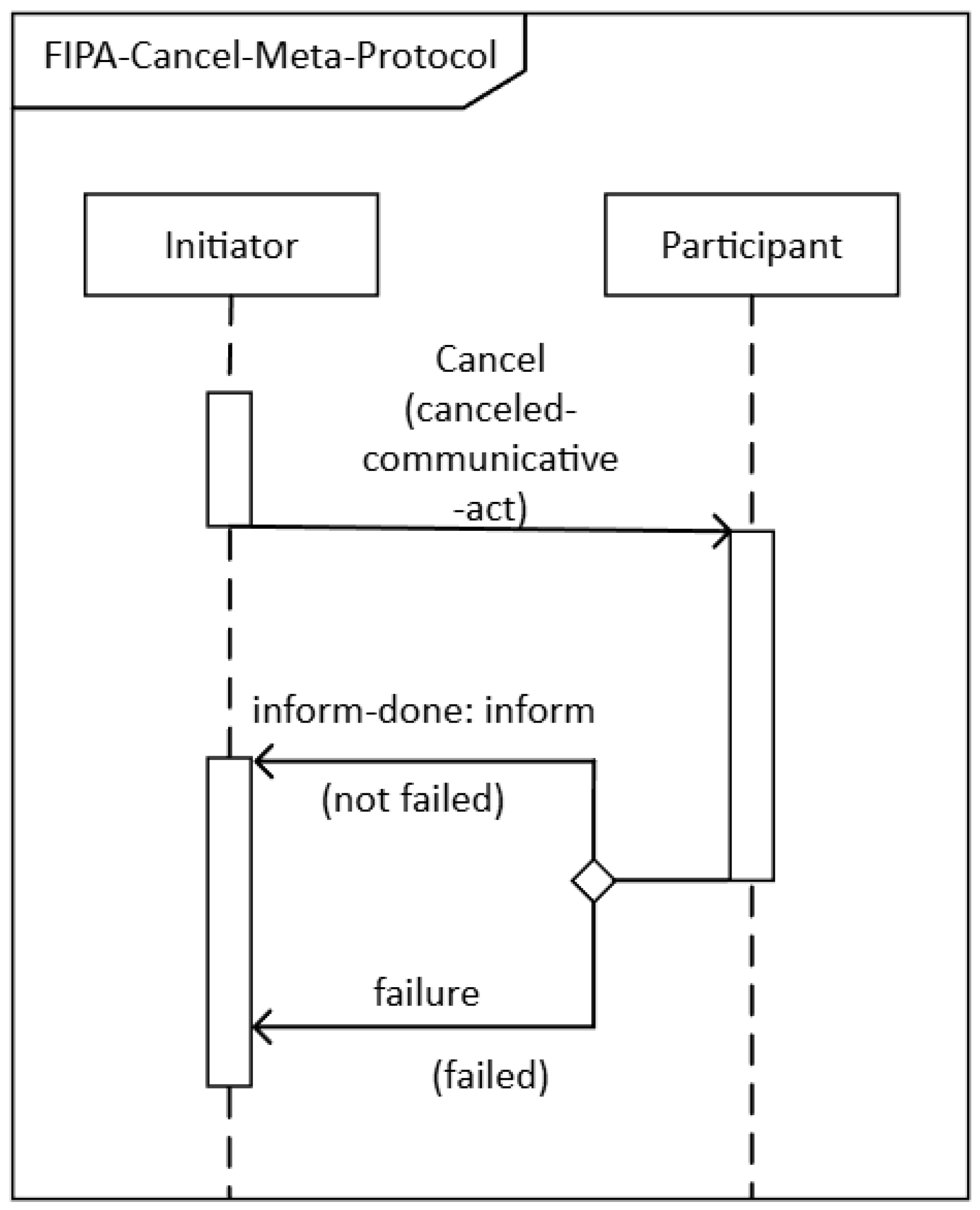

Defining communication via ACL messages—at any point in the conversation, the recipient of an ACL message (

Figure 13) can inform the sender that he did not understand the content of the message, namely with a not-understood message [

44]. This message can terminate the entire IP, which implies that all commitments made during this conversation are invalid. In the case where the IP concerns multiple participants, each response must be evaluated separately, and some of these messages may also be not-understood. For this reason, it may not be appropriate to terminate the entire IP, since participants can continue communicating with their subprotocols [

45].

Canceling mutual holon communication—at any step, the initiator can cancel the IP, namely Fipa-cancel-Meta-Protocol (

Figure 14), which contains the cancel message, and whose conversion-id is the same as the conversation that the initiator wants to cancel. The participant informs the initiator whether the cancelation was successful, namely with the information–done, or that the IP termination failed, namely with the message failure.

Experimental verification of the proposed methodology was carried out in the conditions of the ZIMS workplace. The subject of the experiment was the implementation of information software within the common data network, which met the conditions set out in the algorithm. In another experiment, the functionality of the proposed interaction holon was verified.

It is essential to clarify the system’s operational boundary and performance limitations. The control logic deployed on the Raspberry Pi 4 utilizes a non-real-time operating system (Linux) and is solely focused on higher-level supervisory control, data collection, and flexible task coordination (Level 4/3 according to ISA-95). All low-level, time-critical, and deterministic machine control (e.g., specific timing and safety functions) remains the exclusive domain of dedicated, hard real-time systems, such as Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). The holon acts as the information and coordination wrapper above the PLC level, not as a replacement for deterministic process control.

The full data collection process is formalized into the data collection algorithm (DCA), which executes sequentially within the holon’s operating loop to maintain the required sampling rate:

Low-Level Data Acquisition: The holon’s application layer, built on Python, employs dedicated low-level communication libraries to execute a synchronous read operation. This procedure extracts raw binary or numerical values for a predetermined set of manufacturing parameters, such as component count or cycle time, directly from the physical process controller (PLC).

Data Transformation and Contextualization: Raw data is immediately subjected to a critical transformation process where it is converted into a standardized JSON object. This conversion is vital for resolving semantic heterogeneity by enriching the raw numerical value with essential contextual metadata. This metadata includes the current timestamp, the holon’s unique identifier, the associated machine ID, the specific data type, and the Unit of Measure (UoM).

Local Storage and Publishing Preparation: The newly contextualized data object is concurrently stored within the holon’s local memory or database to establish immediate redundancy. This local caching mechanism ensures data integrity even if the network link is temporarily interrupted. The prepared object is then routed to the network publication service.

REST Publication: Finally, the holon utilizes its embedded micro-framework (the Bottle library) to initiate an asynchronous POST request. This request targets the designated data sink, typically a specialized manufacturing execution system (MES) holon or the central database server. The lightweight, standardized nature of the JSON-based REST payload is specifically optimized to minimize network latency and computational overhead across the holarchy.

4.3.5. Adaptive Fault Handling and Self-Healing

The holon’s defining characteristic of autonomy is realized through its capability to perform adaptive fault handling and basic self-healing actions. This mechanism is crucial for mitigating the systemic risk of a single point of failure and enhancing the overall dependability of the distributed system.

The adaptive cycle is initiated by a Hardware Health Check (HHC), executed periodically by the holon’s internal monitoring daemon. The HHC is a resource-light process that evaluates the status of low-level data acquisition interfaces (e.g., communication connection to the PLC) and monitors local computing resources like CPU load and memory utilization.

Failure Detection and Indication: If the HHC returns a failure (e.g., a communication timeout or excessive memory utilization), the holon immediately updates its internal state register from ‘Operational’ to ‘Degraded’. This critical status change is instantly transmitted to the supervisory Holarchy Manager holon through a dedicated REST API endpoint (e.g., /api/v1/health_status). The request payload includes the holon’s unique identifier and a specific error code.

Manager’s Decision: Upon receiving the ‘Degraded’ status, the Holarchy Manager, utilizing its global view of the holarchy and initiates the adaptive process. The Manager determines whether the fault is local and potentially recoverable (e.g., middleware corruption) or critical (e.g., permanent hardware failure).

Self-Healing/Recovery Action: For recoverable errors, the Manager triggers a remote software update. This is executed via a secure, authorized call to the degraded holon’s maintenance endpoint (e.g., /api/v1/update_middleware). The holon then executes a pre-defined script for updating or reinstalling necessary libraries and reboots, aiming to restore a functional state.

Task Re-routing (if critical): If the fault is deemed non-recoverable, the Holarchy Manager temporarily re-routes the degraded holon’s assigned data collection tasks to an available, adjacent holon within the local holarchy cluster. This dynamic reallocation ensures continuous data flow and maintains the system’s resilience by autonomously adapting to localized failure.

4.4. Industrial Applicability and Future Work

For large-scale industrial deployment, performance testing suggests migrating to an Asynchronous Message Broker architecture like MQTT for high-throughput, event-driven, and scalable communication.

The holon manages higher-level coordination (soft real-time). We explicitly state that low-level, hard real-time control and safety-critical functions remain with dedicated PLCs, which respects the ISA-95 model.

Industrial deployment requires robust security measures, including TLS/SSL encryption for all holon communication and token-based authentication for access control.

4.5. Holon Fault Detection and Recovery

Reliability is paramount in industrial systems. Our holonic architecture implements a robust, two-tiered fault handling mechanism that goes beyond simple notification to ensure system integrity and operational continuity:

Fault detection is executed via a Holon-to-Holon Heartbeat (H2H-HB) protocol.

- 5.

Detection Method: Each Interaction Holon is responsible for continuously monitoring the status of its associated manufacturing holon (or other holons it depends on) by periodically sending a lightweight HTTP GET/status request (the “heartbeat”) to the monitored holon’s Bottle API endpoint.

- 6.

Detection Logic: The monitoring holon implements a data timeout judgment mechanism. A fault is declared if the following occurs:

- a.

The H2H-HB request receives an HTTP error response.

- b.

The request times out for three consecutive attempts.

- 7.

Fault Logging and Notification: Upon declaring a fault, the monitoring holon immediately logs the event (Holon ID: [X] failed heartbeat check) to the MES database and broadcasts an FIPA-ACL message of type INFORM_FAILURE to all other holons specified in its configuration list. This notification allows dependent holons to adapt their routing or planning strategies immediately.

The system employs a decentralized recovery strategy based on the holon’s role:

- 8.

Backup Holon Switching: The architecture utilizes a hot standby for critical holons (e.g., the Production Order Holon). Upon receiving an INFORM_FAILURE message for a critical holon, the designated Backup Holon self-activates and assumes the failed holon’s responsibilities, primarily by taking over the failed holon’s IP address or communication identifier via a service discovery mechanism.

- 9.

Data Breakpoint Continuation: Since data collection is event-driven and logged to the central MES, the recovery process focuses on resuming communication. The newly active (or recovering) holon is designed to query the MES for the last processed production order ID (the “breakpoint”) upon startup. This allows it to immediately pick up the task queue from the last known good state, preventing redundant processing or data loss.

- 10.

Self-Restart and Re-registration: The failed holon’s host (Raspberry Pi) is programmed to automatically attempt a service restart after a brief delay. Once back online, the holon performs a self-diagnostic check and re-registers its status as “Active” or “Standby” to the network via a central discovery service, enabling it to rejoin the collaborative environment.

4.6. MES-Holon Data Interaction and Synchronization

The integration with the Qgadoo MES is critical for connecting the operational planning level (Level 3, ISA-95) with the control and execution level (Level 2/1). This integration facilitates both top-down order execution and bottom-up data reporting, ensuring the holons operate with the latest production context.

The data exchange is managed by the central MES-Interaction Holon, which acts as the primary gateway to the MES database (via a secure RESTful API connection). This holon is responsible for coordinating the flow of key information (

Table 3):

A hybrid data synchronization approach is employed:

Timed Pull for Orders: The MES-Interaction Holon periodically polls the MES for new or updated Production Orders (GET/orders/new). This method balances data freshness with database load.

Event-Driven Push for Status: All manufacturing holons are configured to use a real-time push mechanism (via secure HTTPS POST or an industrial protocol like MQTT, if deployed) to immediately update the MES-Interaction Holon whenever a critical equipment status change occurs. This ensures low-latency awareness of the shop floor state for immediate adaptation.

The data models used for these interactions are standardized, using JSON payload formats for lightweight processing across the holonic network.

6. Conclusions

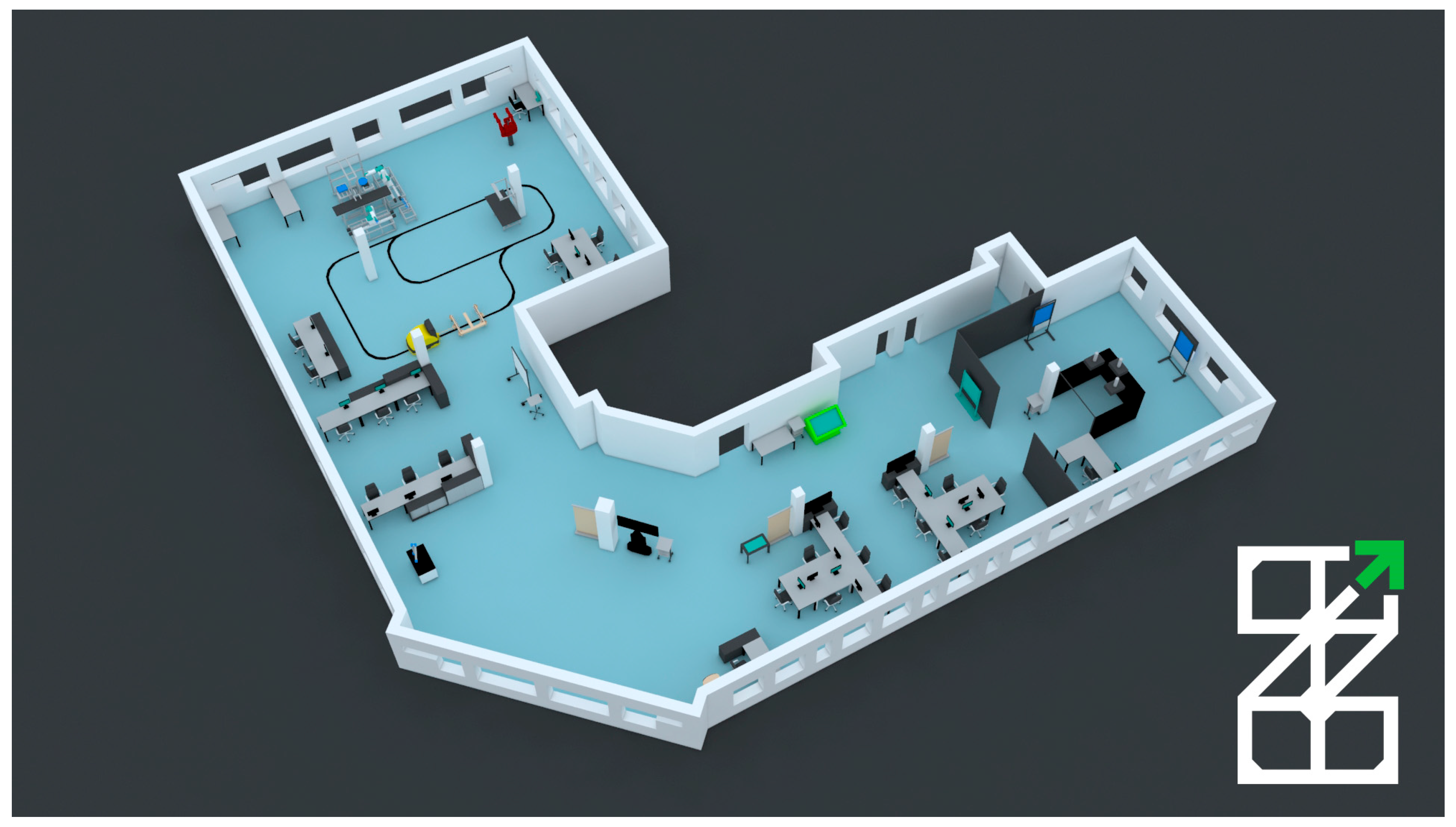

Manufacturing systems are constantly evolving, driven by a wide range of innovative technologies and a growing need to minimize their environmental and social impact. This involves reducing the burden of biological materials on the natural environment and technical materials within the technological environment, while also simplifying these material flows. To address these challenges, a long-term support (LTS) structure is essential. This structure must provide solutions that endure beyond typical lifecycles and consider ongoing innovation, the diversity of requirements, environmental friendliness, and the complexity at various levels and scales. This ensures the system’s adaptability and ability to evolve in response to changing needs. Holonic architecture offers a potential solution for meeting these requirements. The essence of the ZIMS workplace (

Figure 15) is research, development, and experimentation in the field of intelligent manufacturing systems. The effort to connect the design and implementation parts of intelligent manufacturing systems. By applying PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) systems, products are being designed from the very beginning of their design, through the technologies used for production, designing production and logistics processes, to the virtual commissioning and the actual implementation of automated equipment such as industrial robotics, industrial automation, and logistics AGV systems. The ZIMS laboratory is mainly focused on long-term research and not on direct commercial projects.

All systems communicate via the Ethernet network, and their functionality is available via the Internet interface. The network architecture is designed so that it is possible to access the ERP system from the Internet. This decision resulted from the real need to enable access to selected data outside the private network of the company. For example, recording business opportunities of external employees of the company. SCADA/HMI systems are available within the internal network and MES. The architecture of the resulting production system, the operation, and the purpose of the systems is shown in

Figure 16. The resulting architecture integrates the process-level integration by the proposed unified platform with the information systems of the holonic production system.

Specifically, these were the following systems:

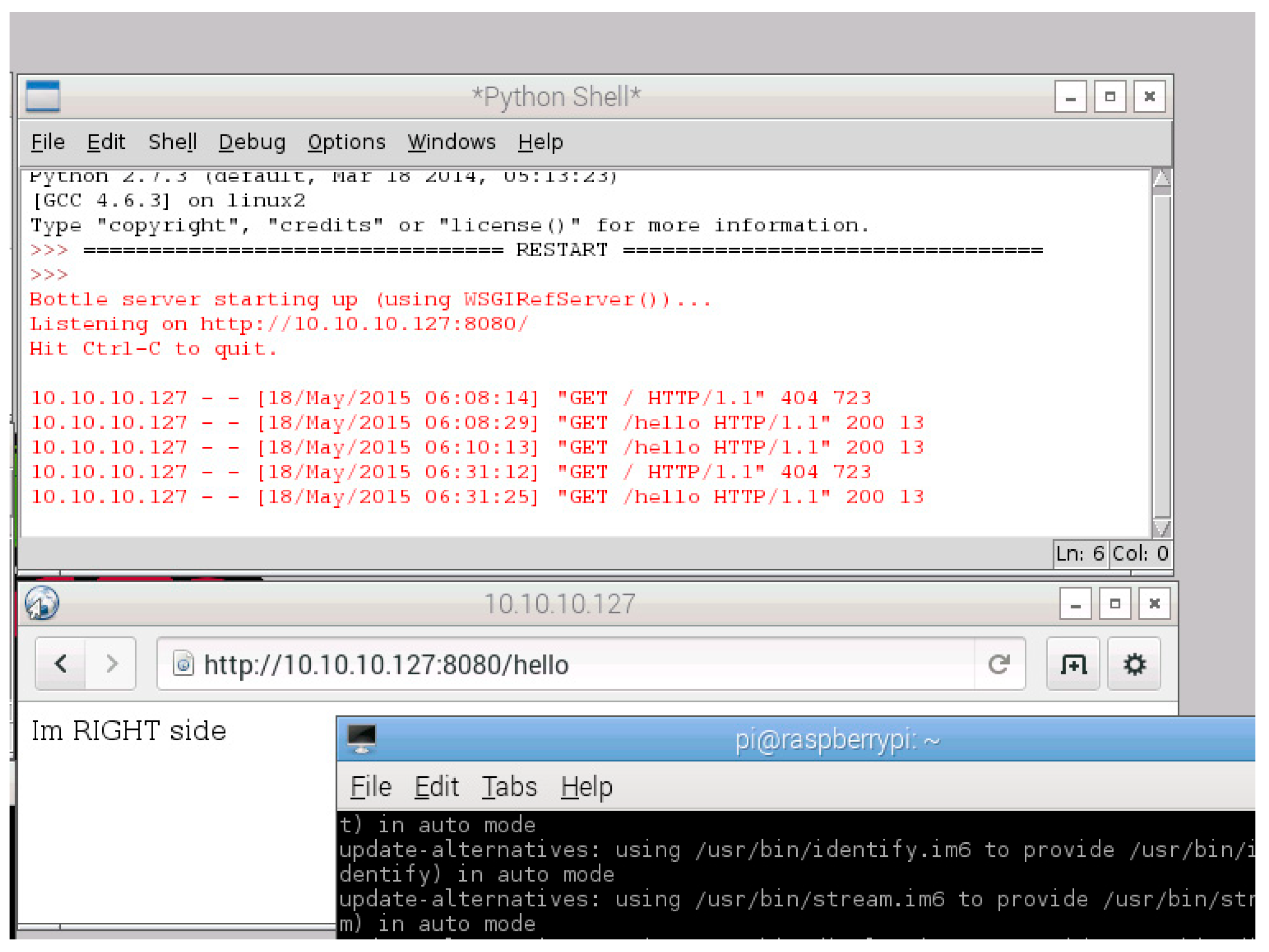

The information systems described at the beginning of the chapter are installed on separate devices. In the case of the MES Qcadoo system, it is a PC equipped with the Ubuntu operating system, the kernel of which is Linux. The ERP system is installed on a Synology server, which also uses an operating system, the kernel of which is Linux. Linux-based operating systems have Python language support in the basic installation. The SCADA/HMI system, which is installed on a PC with the Windows operating system, does not contain Python language support in the basic installation. However, this support can be installed additionally. It is thus possible to apply the interaction holon in the software version to information systems with Python language support without the need for additional technical equipment. To verify the operation of the interaction holon, the task is the ability to interact with another holon in the network. Example in

Figure 19 shows the response to a request that is routed from holon 1 to holon 2, where the response is static text. In a similar way, the code is supplemented with a database connection or with the GPIO port. These records can be deactivated, but during the experimental phase, they provided me with valuable information about the status of the holon web server.

Figure 20 shows a part of the code that illustrates the PYTHON language environment and the syntax of the source code and the return function of the presented function.

Using the software and technical means described in this paper, it is possible to achieve effective collection and management of a holonic production system. The proposed methodology has been verified and its functionality confirmed. However, the activities listed in the methodology algorithm outside the marked area of future research are equally important and time-consuming. It is their correct analysis and specification that determines the final length of the integration of holonic control into the production system. The proposed and verified methodology can ensure the sustainability of the solution in terms of further support for communication interfaces, which are currently a trend. However, the question remains of defining responsibility and guarantees for possible system failures in the event of a malfunction in the case of a holon interaction failure, whose creator may not be the manufacturer of the production equipment. However, these and other questions are more of a legislative nature.

Technically, it is possible to modify the proposed system or implement it in different programming languages or computing devices. The condition is to maintain the structure of requests and responses in REST communications. The HTTP protocol thus enables easier interconnection of systems in terms of complexity and security of communication, which companies require to the maximum extent possible. The proposed communication eliminates the isolation of systems in terms of the use of separate databases, but rather a common database, thereby eliminating the duplication of production data, which will lead to increased efficiency in data collection.

Today’s automatic control systems are generally centralized and strictly hierarchical [

46]. This is how entire large-scale industrial networks are built today, connected to programmable controllers that also operate in a centralized mode. Unlike centralized systems, multi-agent and holonic systems represent a dynamic, easily expandable alternative. The system can respond very effectively to changes caused by the arrival of a priority order or the failure of a production unit, with its response proportional to the severity of the cause. One specific agent will attempt to solve the problem, and if it fails, it will request the cooperation of surrounding agents. The structure of production lines and the production process are not fixed in the control system structure, but are created dynamically when a new order is created. They are automatically adjusted with each change. Since the control and planning process is distributed across a larger number of computing units, the risk of instability caused by the failure of a single agent is minimized. Many applications require highly distributed control [

47].

These include applications in the chemical industry or in the distribution of electricity, gas, or water, where it is necessary to have autonomous units that perform many interventions in the controlled technology independently, without communication with the center. In flexible production sections, it is sometimes necessary to replace, add, or remove certain equipment during operation, not only due to failure or maintenance, but also when changing the production plan. It is important to find a new production path as quickly as possible for each such change. Holonic and multi-agent systems are a suitable solution for all these purposes.

An example is a conveyor system where one conveyor malfunctions. In a classic setup, it is necessary to stop production, reprogram the line, and restart it. With agent control, it works differently: as soon as the device detects a malfunction, it notifies all other devices that are interested. They immediately begin to discuss a replacement solution and send the products via a different route. When the conveyor is repaired, it sends a message that it is ready for operation and agrees with the surrounding devices regarding what it can do for them. Nothing must be stopped or reprogrammed; everything works completely automatically. Holonic and multi-agent systems are, therefore, much more flexible and robust than traditional centralized control, allowing the configuration of the production system and production plans to be changed automatically.

This adaptable architecture offers a resolution to the intrinsic difficulties associated with distributed systems. Its strength resides in the deployment of an adjustable aggregation paradigm, unconstrained by a rigid central authority and instead capitalizing on the self-governance and collaborative nature of individual holons. Empirical validation demonstrated that crucial system-wide information, including diagnostic data and key performance metrics (KPIs), can be effectively accumulated without compromising the autonomy of individual production units. The integration of a standardized communication protocol (e.g., MQTT or OPC UA) facilitated fluid interconnectivity between disparate elements, a vital aspect for the enduring viability and adaptability of the holonic manufacturing system (HMS). The capacity of holons to perform data processing locally (edge computing) and transmit only pertinent summaries or notifications (event-driven architecture) considerably mitigates latency and facilitates near-instantaneous reaction times. Future investigations should prioritize refining the dynamics of the information structure for exceedingly large populations of holons, with particular emphasis on data soundness and safety within the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) context. Simulated cyberattack testing would further yield valuable perspectives on the system’s robustness. In summary, the presented methodology not only enhances the efficiency of data acquisition within a holonic setting but also establishes a foundation for sophisticated analytical instruments, such as anticipatory upkeep and self-regulating production oversight, thereby propelling the advancement toward fully independent manufacturing systems.