A Methodology for Designing High-Efficiency Power Amplifiers Using Simple Microstrip Harmonic Tuning Circuits

Abstract

1. Introduction

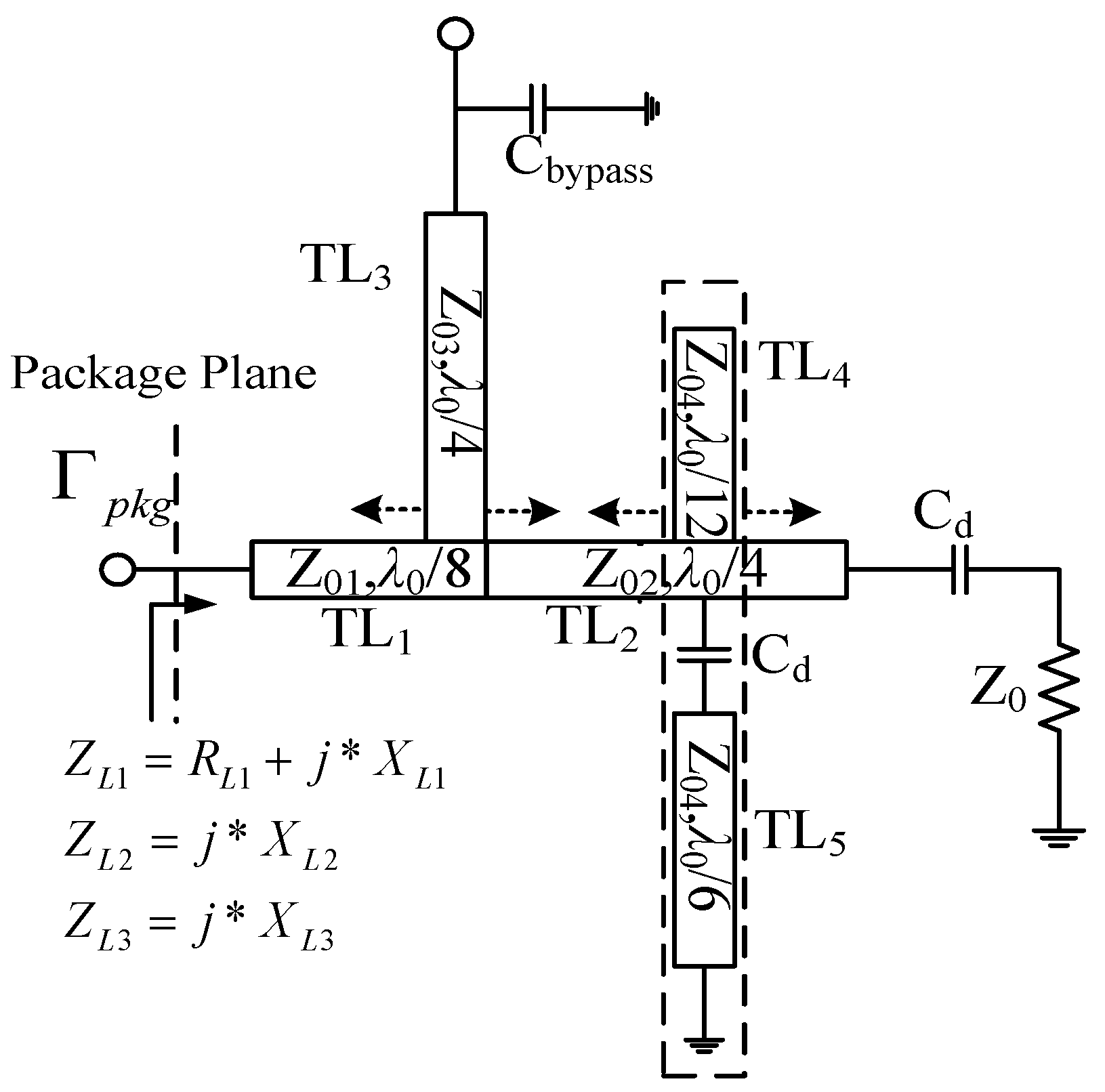

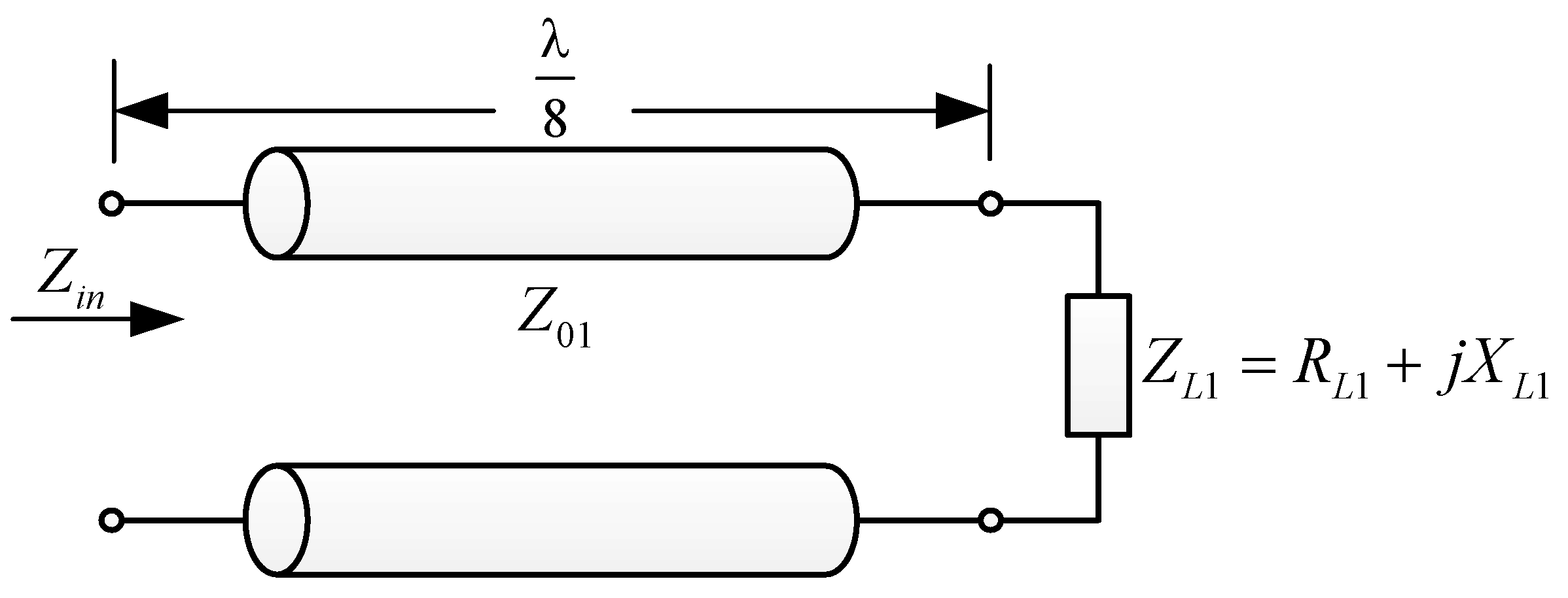

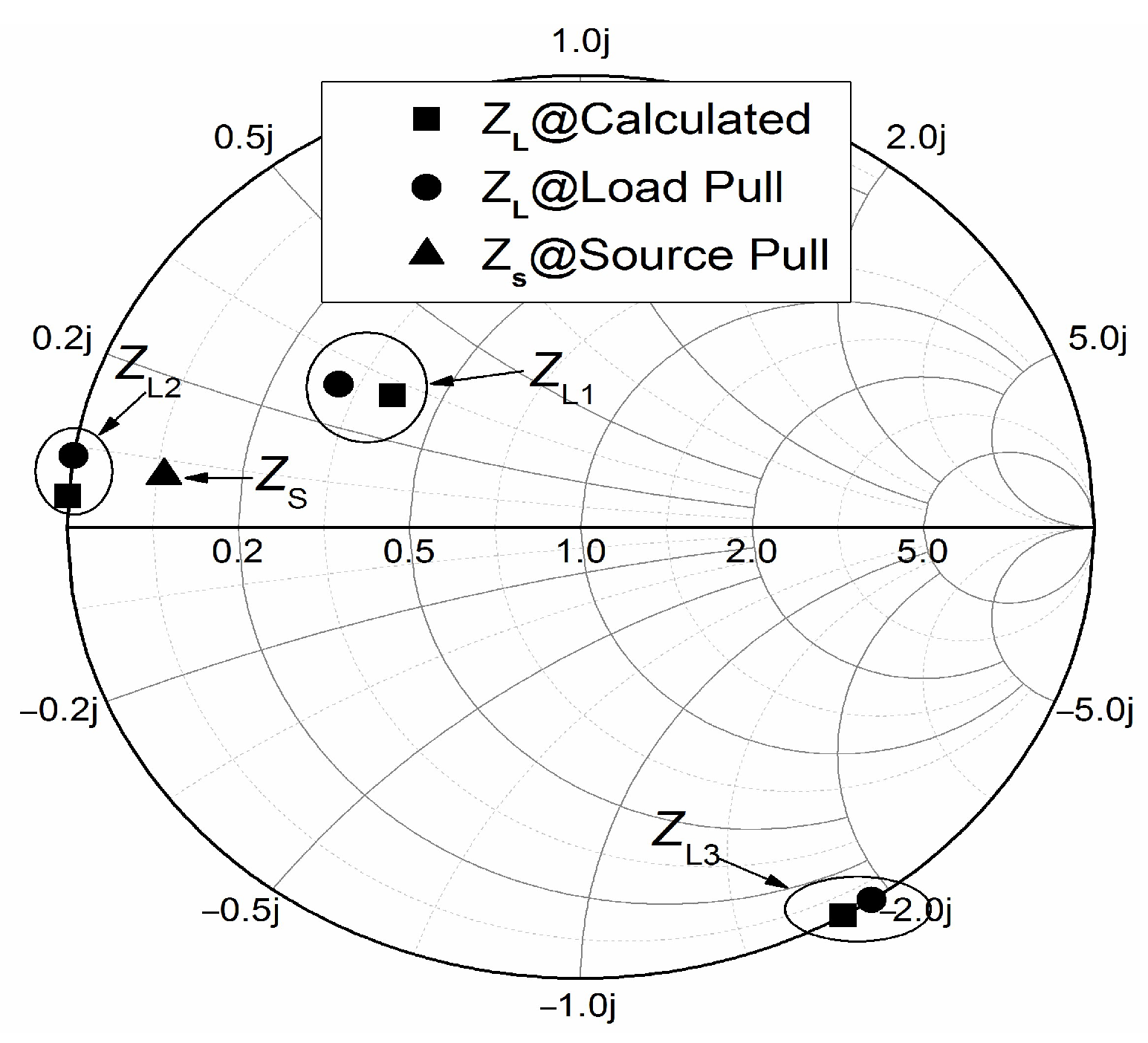

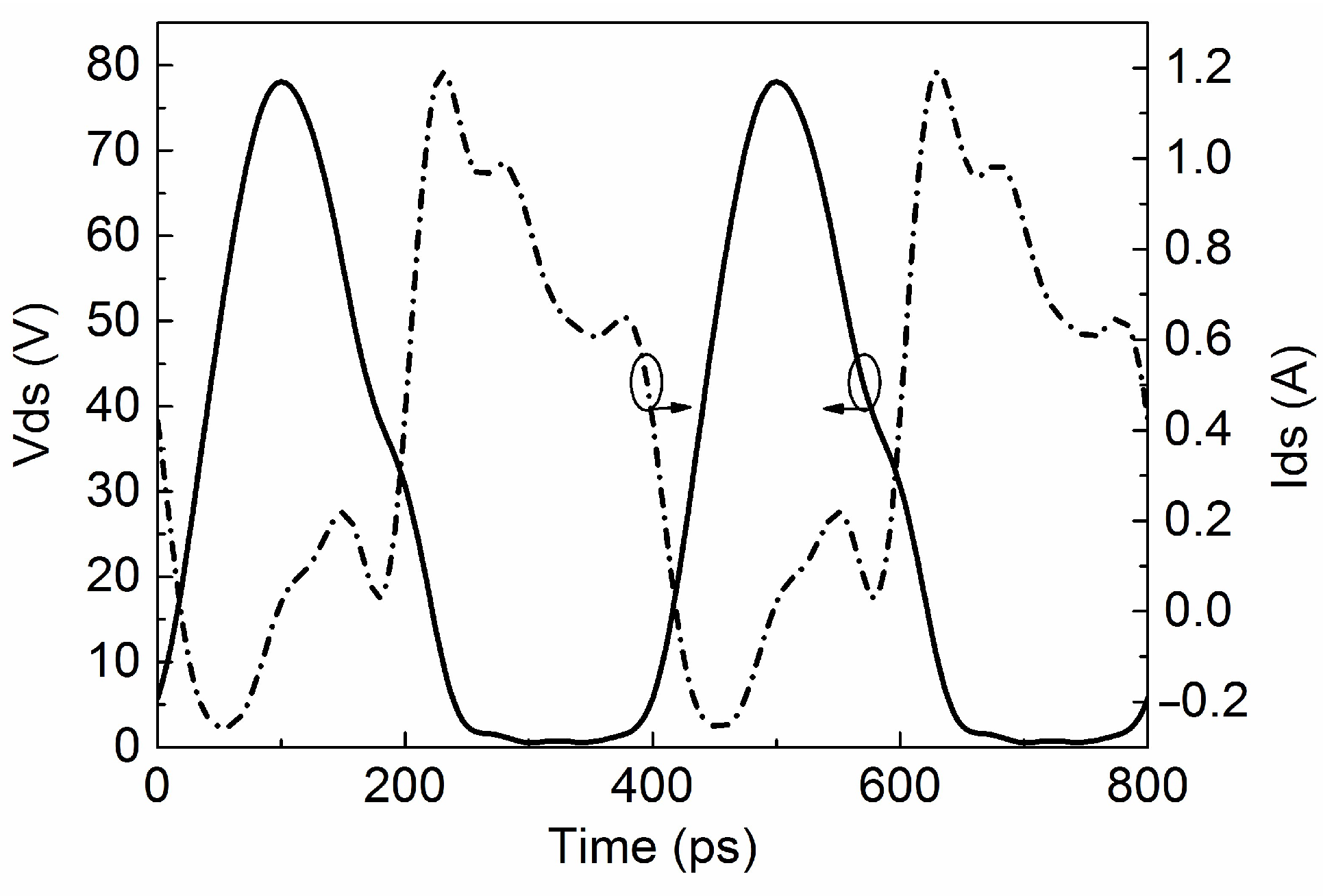

2. Design Methodology

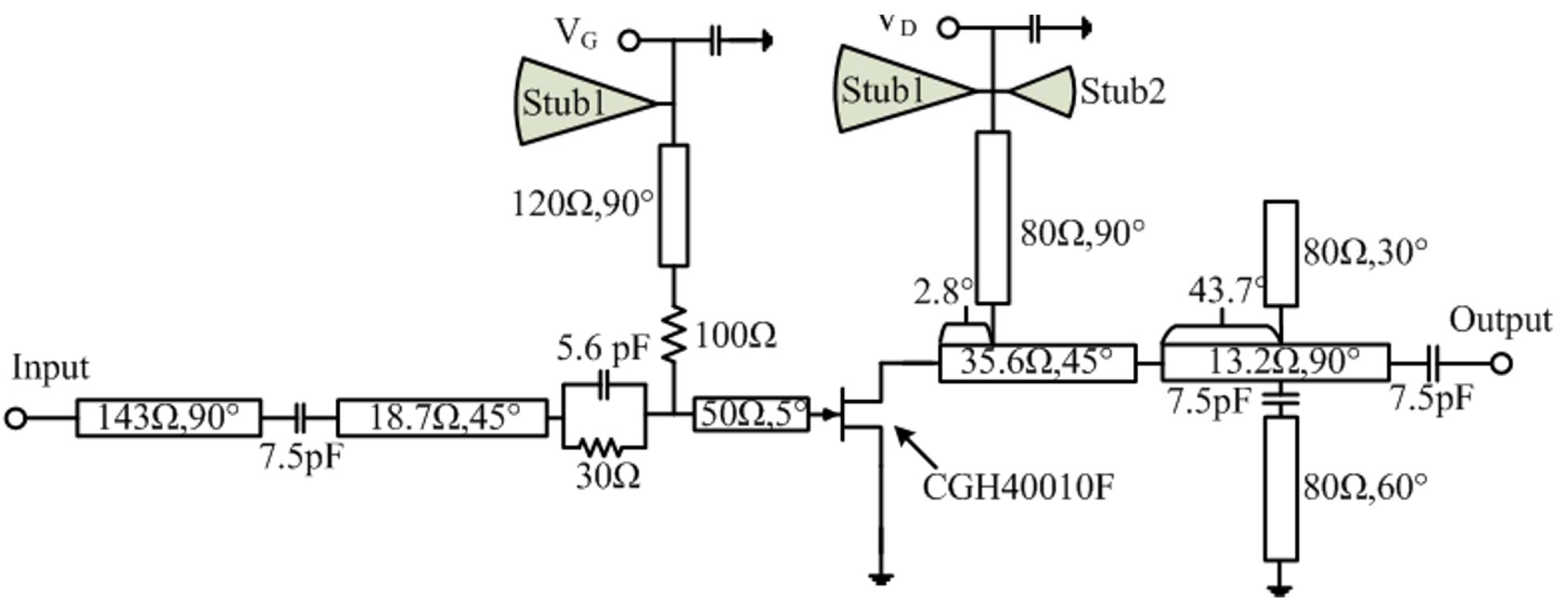

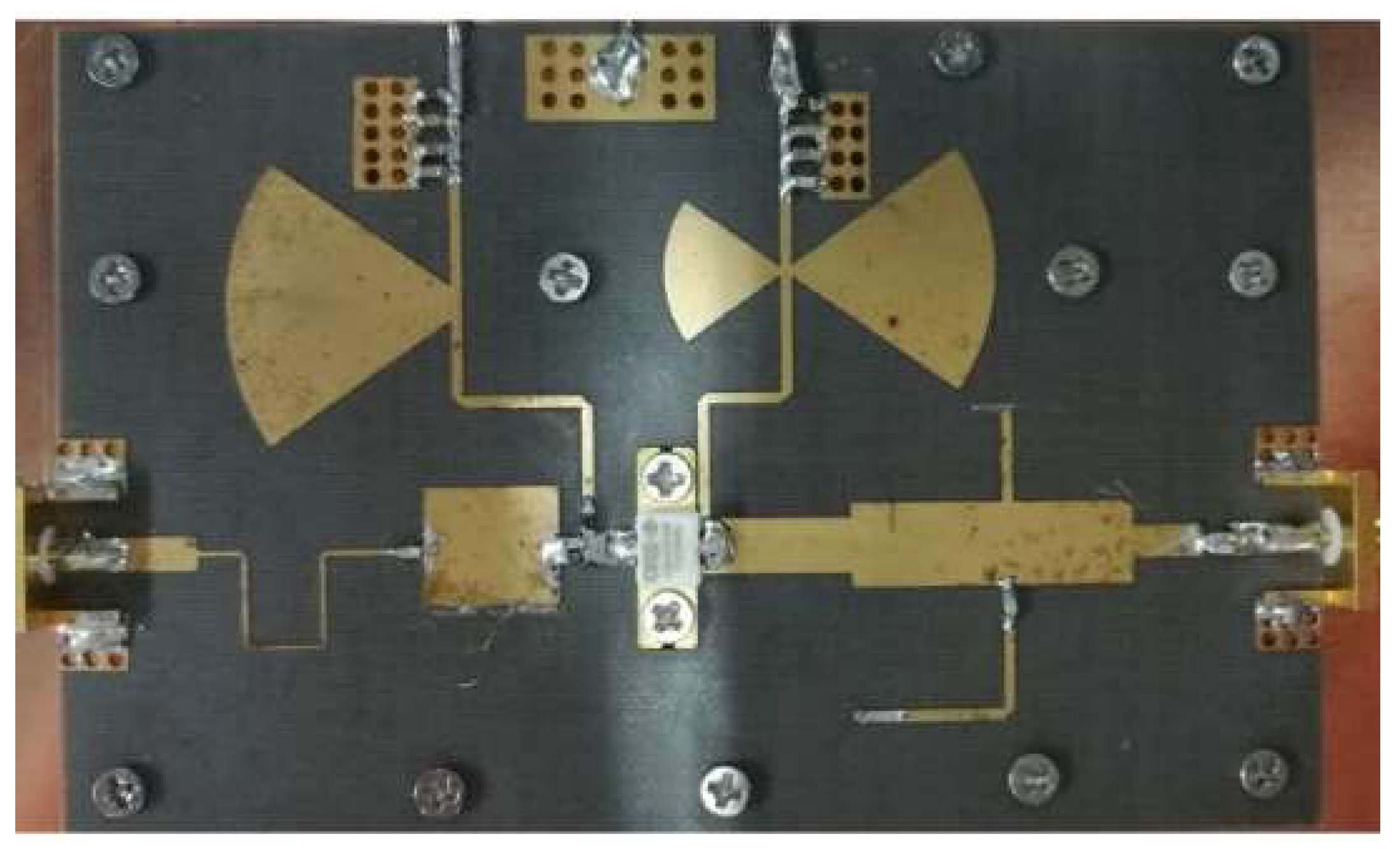

3. Design and Verification

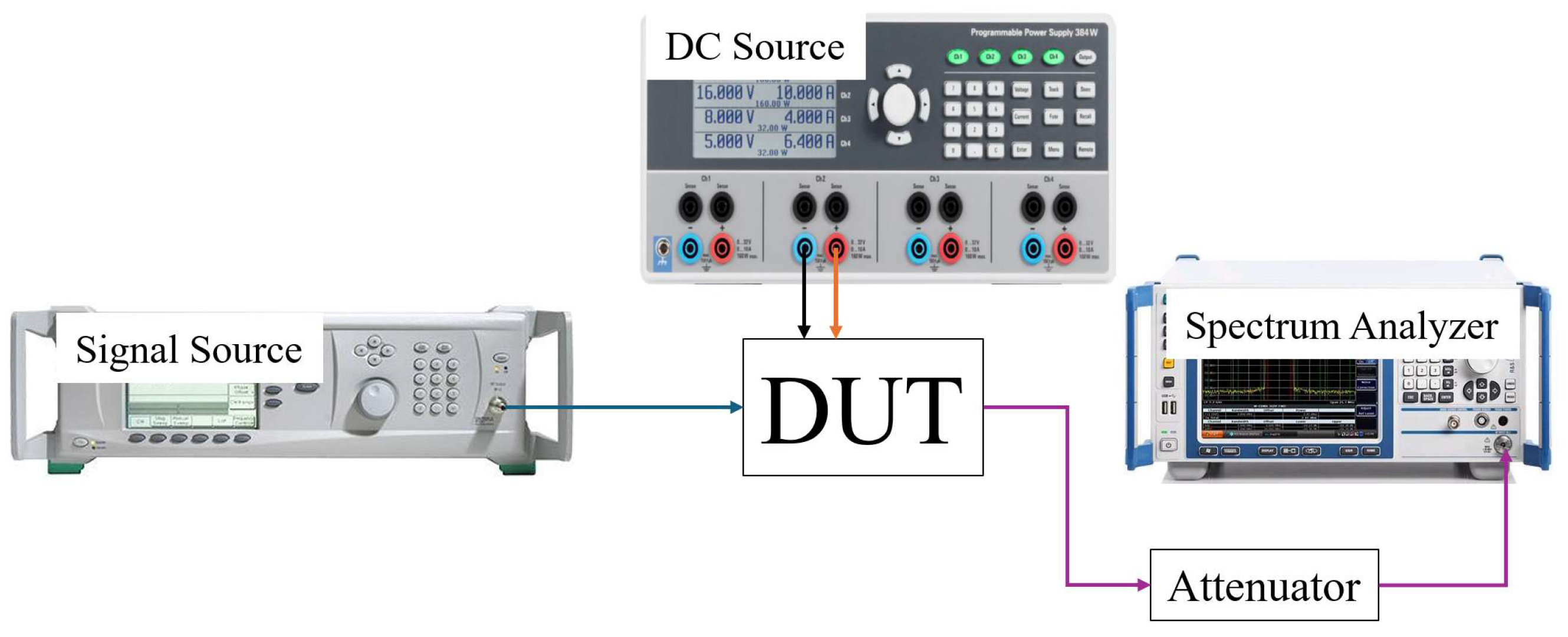

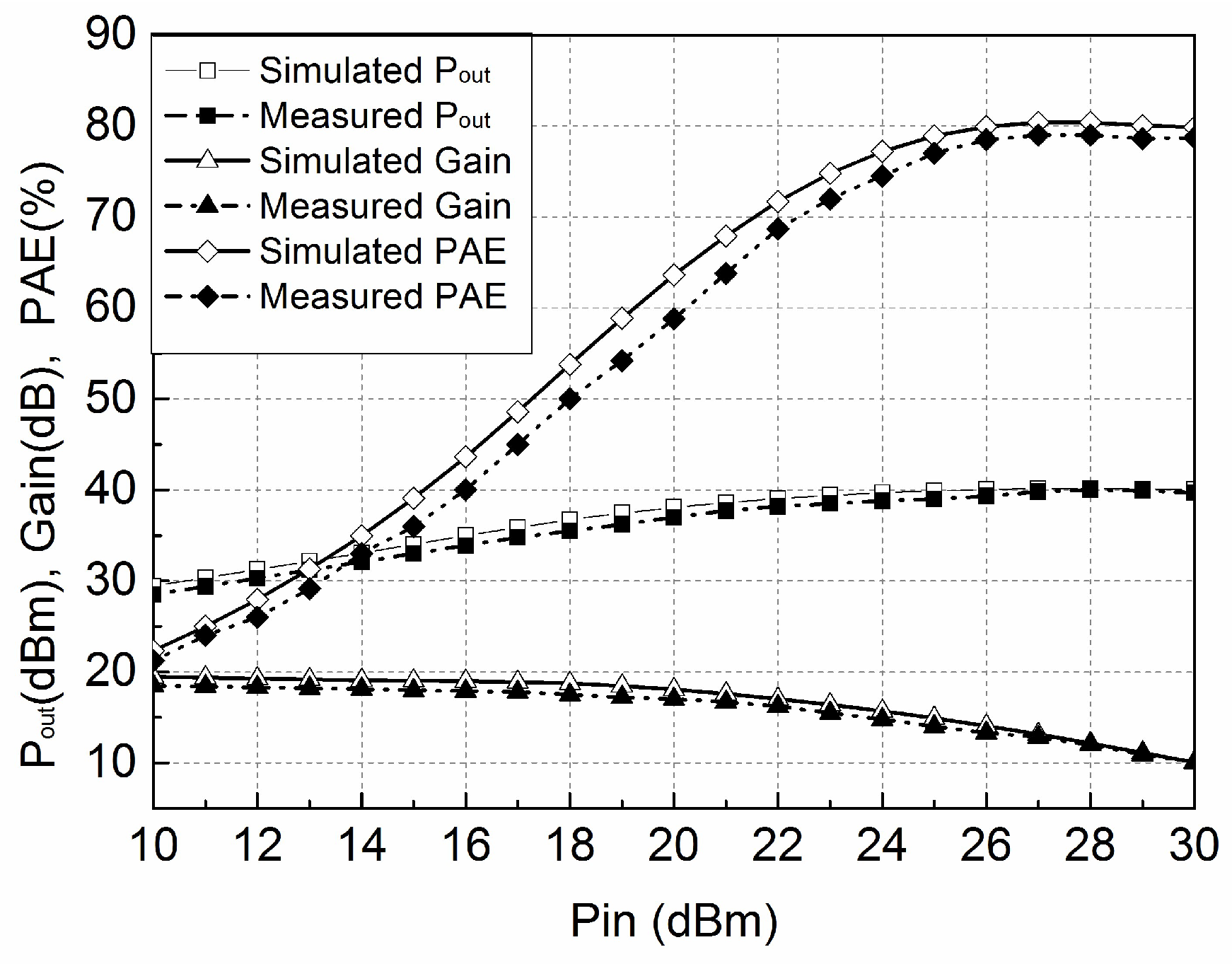

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, M.; Gao, R.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Shi, W.; Dai, Z.; Chen, S.; Pang, J. Design of Wideband Doherty Power Amplifier Using Inverse Continuous Class-F Mode. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 4176–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanaatian, A.; Abrishamifar, A.; Rahmati, A.; Alizadeh, A. A 15-W X-Band Inverse Class-F GaN Power Amplifier with Second-Harmonic Input Tuning. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Technol. Lett. 2023, 71, 1317–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.; Kamran Saleem, M.; Maalik, A.; Ikram, M. Hybrid Load-Pull and Nonlinear Embedding Approach for High-Efficiency GaN Class-F/F−1 Power Amplifier Design in Satellite Applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 173768–173789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Fan, R.; Yan, L.; Feng, Y.; Liu, C. Design of a High-Power and High-Efficiency GaN-HEMT VCO Based on an Inverse Class-F Amplifier. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Technol. Lett. 2025, 35, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.-H.; Chuang, K.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chang, D.-C.; Hsu, S.S.H. A Continuous-Mode Class-F−1 X -Band Gan Mmic Power Amplifier with a 29.7. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium-IMS 2025, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Li, H.; Liu, F. Design of a High-Efficiency Multi-Octave Continuous Class-GF−1 Power Amplifier with In-Band Flexible Operation. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Xi’an, China, 19–22 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Y.W.; Yang, Y.; Kim, B. Analysis and experiments for high-efficiency class-F and inverse class-F power amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2006, 54, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.F.; Fu, H.-P.; Zhu, S.-K.; Wu, H.-F.; Ma, J.-G. High-efficiency GaN Class-F/Class-F−1 power amplifiers with distributed L-shaped parasitic-compensation circuit. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2015, 57, 2441–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, M.; Jeong, Y. High-Efficiency Class-F GaN HEMT Amplifier with Simple Parasitic-Compensation Circuit. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2008, 18, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xue, Q. A Class-F Power Amplifier with CMRC. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2011, 21, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, M.; Sheikhi, A.; Grebennikov, A. Class-F Power Amplifier with High Power Added Efficiency Using Bowtie-Shaped Harmonic Control Circuit. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2015, 25, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, M.; Shama, F. A high-efficiency narrow-band Class-F power amplifier integrated with a microstrip suppressing cell. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2017, 90, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, R.A. Class-F and inverse class-F power amplifier loading networks design based upon transmission zeros. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS2014), Tampa, FL, USA, 1–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Guo, Y.-X.; Liu, F. A new method to design high efficiency power amplifier using dual-band transformer. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference 2011, Melbourne, Australia, 5–8 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrecher, D.H. An Interesting Impedance Matching Network. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 1967, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.F.; Fu, H.P.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Ma, J.-G. High-efficiency parallel-circuit class-E power amplifier with distributed T-shaped compensation circuit. IEICE Electron. Express 2016, 13, 20160570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, L.; Wei, M.-D.; Negra, R. High-Efficient Inverse Class-F Power Amplifier Utilising Nonuniform Transmission Lines for Wireless Power Transfer. In Proceedings of the 2024 31st IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Nancy, France, 18–20 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Piacibello, A.; Zhang, Z.; Camarchia, V. Continuous Inverse Class-F GaN Power Amplifier with 70% Efficiency over 1.4–2 GHz Bandwidth. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Topical Conference on RF/Microwave Power Amplifiers for Radio and Wireless Applications, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–25 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Dong, Q.; Huang, W.; Jiang, X.; Wei, K.; Liu, X.; Luo, W. A High-Efficiency Inverse Class-F GaN MMIC Power Amplifier with Compact Output Matching Network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 3767–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilla, C.D.; Alsaedi, M.O.H.; Alsaadi, H.A.J. Design Continues Mode Inverse Class-F Power Amplifier. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Istanbul, Turkey, 27–28 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Oh, J. Dual-Band Continuous Class-F−1 Power Amplifier with Second-Harmonic Suppression for Harmonic Radar Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 62358–62364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Q.; Du, G.; Li, G.; Cheng, D. Dual-Band High-Efficiency Power Amplifier Based on a Series of Inverse Continuous Modes with Second-Harmonic Control. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Technol. Lett. 2023, 33, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Mode | Frequency (GHz) | Pout (dBm) | PAE (%) | Gain (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9]-2018 | Class-F | 2.14 | 40.2 | 70.9 | 12.2 |

| [12]-2017 | Class-F | 1.8 | 23.4 | 73.5 | 17.5 |

| [13]-2014 | Class-F−1 | 0.3 | 42.37 | 79 * | 11.37 |

| [16]-2016 | Class-E | 2.9 | 40.2 | 72.2 | 12.2 |

| [1]-2024 | Class-F−1 | 0.7–1.1 | 42.6–43.3 | 66.0 *–74.6 * | 13.5–16 |

| [17]-2024 | Class-F−1 | 2.3–2.55 | 36.76 | 72.7 | 13.4 |

| [18]-2023 | Class-F−1 | 1.4–2.0 | 40 | 70 | 13 |

| [19]-2023 | Class-F−1 | 3.0 | 38.4 | 64.5 | 10.3 |

| [20]-2023 | Class-F−1 | 1.5–2.0 | 40–40.1 | 70.4 | 16 |

| [21]-2024 | Class-F−1 | 2.3/3.35 | 40.34/41.9 | 72.6/59.5 | 12.9/8.8 |

| [22]-2023 | Class-F−1 | 3.37–3.52 | 40–41.2 | 65–76.2 | 8.8–11.2 |

| [6]-2025 | Class-GF−1 | 0.6–2.8 | 39.8–42.5 | 65 *–74 * | 9.8–13.28 |

| This work | Class-F−1 | 2.5 | 40.2 | 79.8 | 12.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Zhou, S. A Methodology for Designing High-Efficiency Power Amplifiers Using Simple Microstrip Harmonic Tuning Circuits. Electronics 2025, 14, 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234767

Zhang G, Zhou S. A Methodology for Designing High-Efficiency Power Amplifiers Using Simple Microstrip Harmonic Tuning Circuits. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234767

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guohua, and Shaohua Zhou. 2025. "A Methodology for Designing High-Efficiency Power Amplifiers Using Simple Microstrip Harmonic Tuning Circuits" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234767

APA StyleZhang, G., & Zhou, S. (2025). A Methodology for Designing High-Efficiency Power Amplifiers Using Simple Microstrip Harmonic Tuning Circuits. Electronics, 14(23), 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234767