1. Introduction

Quantum computing represents one of the most dynamically evolving fields of contemporary science and technology, with revolutionary potential for computational paradigms that were previously considered intractable for classical systems [

1]. The unique properties of quantum mechanics, such as superposition or entanglement, enable quantum computers to solve problems significantly faster than classical computers. The new quantum approach will find implications across multiple domains, from changing the foundation of cybersecurity and cryptography to affording novel opportunities in drug discovery, finances, and logistics, ultimately paving the way for future development, such as creating new opportunities for machine learning [

2,

3]. Furthermore, progress in quantum algorithm development has made the transition to post-quantum cryptography imperative [

4]. Despite remarkable progress over the past two decades, the development of practical, scalable quantum computers continues to encounter fundamental challenges rooted in the physics of quantum systems. The major problem among these is the quantum error correction problem, which arises from the unstable and fragile nature of quantum information. Qubits, quantum information carriers, unlike the classical bits, cannot be corrected by simple redundancy. Their quantum nature forces us to use sophisticated correction strategies [

5].

In this work, we present the first implementation of a surface code pipeline, implementing the surface code pipeline—one of the most promising quantum error correction approaches today—within the Qrisp framework, a high-level quantum programming language. Subsequently, practical experiments were conducted on real quantum computers available to the research community. The experimental evaluations were performed using the available IQM quantum machines. During the testing phase, the pipeline was executed under various parameter configurations to generate a comprehensive dataset, enabling a thorough analysis and formulation of conclusions. Crucially, this work identifies and quantifies the dominant architectural constraint of current superconducting hardware for QEC.

This paper is organized into six sections. The following section introduces the fundamental concepts of quantum error correction methods.

Section 3 discusses surface codes, describing their applications, advantages, and limitations.

Section 4 presents implementation details accompanied by multiple code examples. Subsequently,

Section 5 provides the obtained results and the corresponding analysis. The final section concludes this paper.

2. Quantum Error Correction

A key challenge in quantum computing is quantum error correction, necessitated by the fragile nature of qubits that cannot be stabilized through simple redundancy but require advanced correction strategies [

6]. The instability and vulnerability of quantum systems are primarily caused by factors which are briefly introduced below.

Decoherence

The interaction between the environment and the quantum system causes loss of coherence, leading to the decoherence of quantum information. This results in the loss of the ability to maintain superposition and entanglement. Decoherence times in current quantum hardware typically range from microseconds to milliseconds, imposing severe constraints on computational depth.

Quantum Noise

Quantum operations are extremely fragile and are strongly exposed to quantum noise. Noise comes from various sources, such as amplitude damping, which is caused by losing energy in the environment; phase dephasing, which is losing phase without losing energy; depolarizing noise; and thermal fluctuations.

Gate Imperfections

The implementation of physical quantum gates is imperfect. Typical single-qubit gate fidelities are around 99.9%, and two-qubit gate fidelities are around 99%. These error rates accumulate rapidly in deep quantum circuits.

Measurement Errors

Current methods and technology to read the process cause some errors. Typical measurement fidelities are around 97–99% in superconducting systems.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the impossibility of cloning. One of the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics—the no-cloning theorem—prohibits the duplication of unknown quantum states. Consequently, simple redundancy-based error correction methods cannot be applied. This necessitates indirect methods of error detection and correction that preserve quantum information without collapsing superposition states.

To resolve the quantum error correction (QEC) problem, there are several QEC code families. We can distinguish Shor codes [

7], Steane codes [

8], concatenated codes, and low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes [

9]. Each of them has a different balance between the implementation complexity, qubit overhead, and correction capabilities. Various approaches have been proposed, from which the family of surface codes has emerged as the dominant solution for fault-tolerant quantum operations.

Surface codes are topological quantum error correction codes. Topological Quantum Computing (TQC) is a computational paradigm that protects quantum information by encoding it within the global, topological properties of a physical system. Unlike conventional approaches, TQC safeguards logical qubits through the entanglement of multiple physical qubits, where the conventional approach store them locally. The TQC approach makes logical qubits robust against local perturbations. Codes such as the surface code are prime examples of TQC, utilizing a two-dimensional lattice structure where stabilizer measurements assess the parity of errors on neighboring data qubits. This topological redundancy implies that a logical error can only occur through the cooperative failure of many physical errors, forming a continuous chain (error chain) with a length equal to the code distance (

d). Due to their high scalability potential and growing adoption in the quantum computing industry, surface codes constitute one of the most promising directions for ongoing research and technological development [

10].

3. Surface Codes

Recent advances in quantum error correction have demonstrated that practical implementations of the surface code are fundamentally constrained by hardware-level features such as native reset availability, gate fidelities, qubit connectivity, and the achievable depth of repeated stabilizer–extraction cycles. These limitations are widely recognized in the literature and have been observed across multiple platforms, including superconducting and trapped-ion architectures. The purpose of the present work is therefore not to revisit these well-established constraints but to examine their concrete operational impact within the Qrisp-Qiskit-IQM execution stack.

Surface codes belong to the topological QEC codes family, which encodes quantum information not in individual qubits but in global topological properties of a two-dimensional lattice structure [

11]. These codes provide robustness against local errors due to the distribution of quantum information across multiple physical qubits, combining them into a single logical qubit. The structure of a logic qubit endures such that single or even multiple localized errors cannot destroy the encoded state. The topological code family includes toric codes, defined on a torus topology with periodic boundary conditions; planar codes, defined on a planar lattice with physical boundaries; and higher-dimensional toric codes, which generalize the concept to dimensions (greater than two), enhancing fault tolerance and enabling more complex topological quantum phases. This paper is focused on surface code based on a planar lattice. Surface codes require two types of stabilizer operators. Each of them is designed to detect a specific type of quantum error.

X-stabilizers, also called star operators, are positioned at the vertices of the lattice and measure the parity of Pauli

X operators applied to the surrounding data qubits. These stabilizers detect

Z-errors, which correspond to phase-flip errors in the quantum state, and take the following mathematical form:

where the product runs over the indices of the four data qubits adjacent to the vertex

v.

Z-stabilizers are positioned at the centers of the square plaquettes and measure the parity of Pauli

Z operators applied to the surrounding data qubits [

10]. These stabilizers detect X-errors, which correspond to bit-flip errors, and take the following form:

where the product runs over the four data qubits that form the boundary of the plaquette

p.

The logical operators that act on this encoded qubit are represented by non-contractible loops of Pauli operators that span the entire lattice and cannot be detected by any local stabilizer measurement. The logical X operator corresponds to a string of X operators connecting one pair of opposite boundaries, while the logical Z operator corresponds to a string of Z operators connecting the perpendicular pair of boundaries.

Error detection in surface codes operates by syndrome measurement patterns that reveal error locations without collapsing the encoded quantum state [

12]. When a physical error E occurs on one or more data qubits, any stabilizer operator that anti-commutes with the error operator will flip from its normal eigenvalue of +1 to −1, while stabilizers that commute with the error remain at +1. The set of violated stabilizers, those measuring −1, forms a syndrome pattern that serves as an error signature. X-errors, which stand for bit-flips, create pairs of violated Z-stabilizers at the endpoints of an error chain, while Z-errors produce pairs of violated X-stabilizers. Errors can terminate at the physical boundary of the code, represented mathematically by introducing virtual boundary stabilizers. The crucial property enabling quantum error correction is that the syndrome pattern reveals the locations where errors have occurred without revealing the actual quantum states of the data qubits, thereby preserving the quantum information encoded in superposition and entanglement.

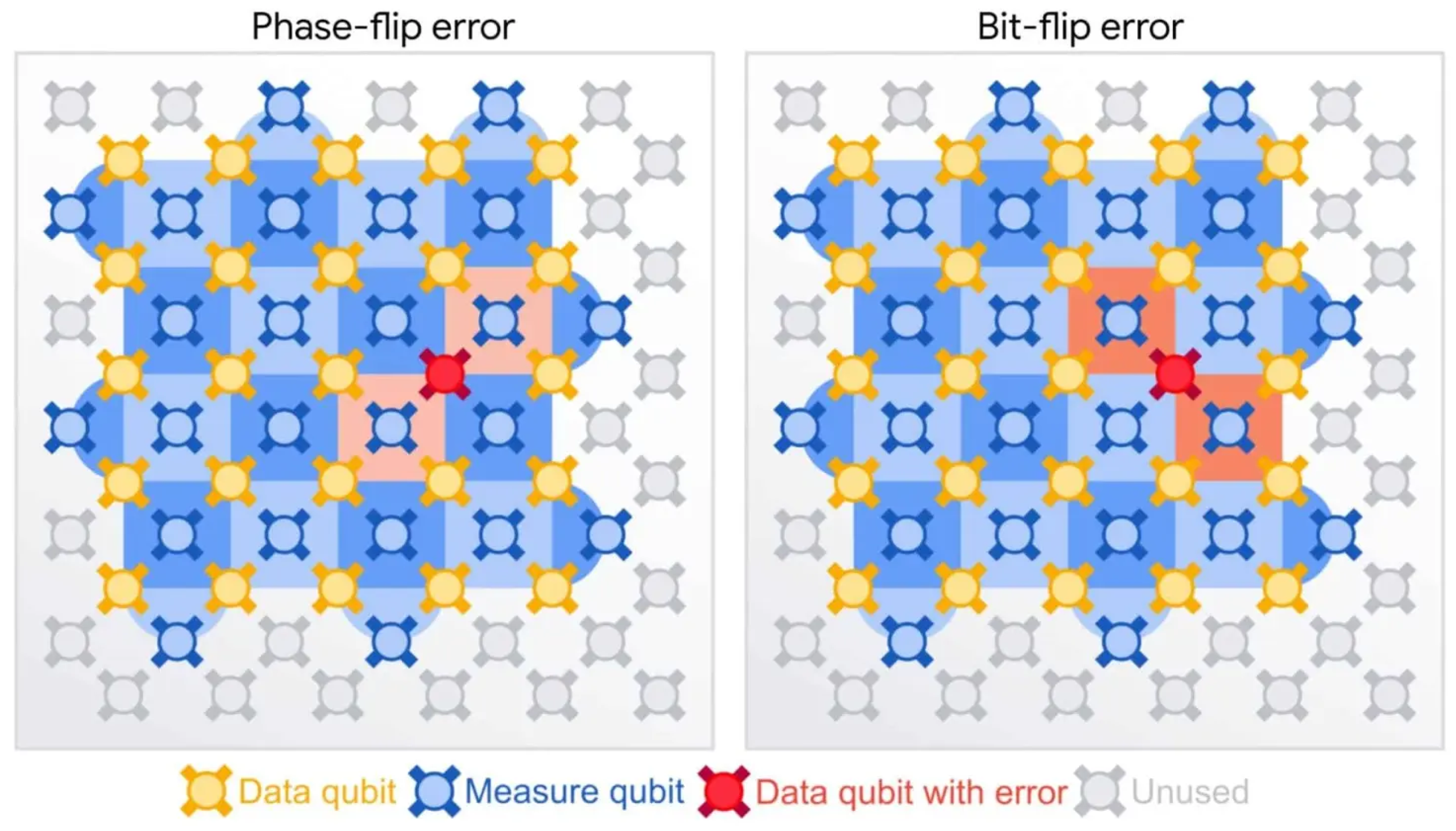

Figure 1 illustrates the functioning of the surface code [

13]. The yellow object represents data qubits, and the blue object represents measurement qubits. The dark-blue plaquette represents the X-stabilizer to detect bit error, and the light-blue plaquette represents the Z-stabilizer for the detection of phase-flip error. The left panel shows the detection of a phase-flip error, where two Z-stabilizers are triggered by the error of the defective data qubit—the red one. The right panel illustrates the detection of a bit-flip error by X-stabilizers.

3.1. Measurement Protocol

Syndrome extraction, due to the quantum nature, requires quantum circuits that entangle ancilla qubits with data qubits according to the stabilizer to avoid direct measurement of data qubit state. The Z-stabilizer measurement follows a specific circuit protocol to detect bit flips:

Initialize the ancilla qubit in state |0⟩;

Apply a sequence of CNOT gates from the ancilla as control, to each of the four surrounding data qubits which are targets;

Measure the ancilla qubit on the computational basis.

The outcome of the measurement is 0 or 1. The value directly indicates whether an even or odd number of X-errors have occurred in the measured data qubits. A value of 0 indicates no error or even numbers of errors; each two errors will blur themselves, so even numbers give the same output as zero errors. A value of 1 indicates one error or an odd number of errors. With odd numbers, there is always one error that does not have a pair to blur itself, so it gives some output like one error. Measurement reveals the stabilizer without direct measurement of the data qubit because the CNOT gates only propagate the parity information to the ancilla without extracting individual qubit values.

The X-stabilizer measurement uses a different circuit protocol to detect phase flips:

Apply a Hadamard gate to the ancilla qubit initialized in |0⟩;

Rotate it into the |+⟩ state;

Apply a sequence of CNOT gates with reverse direction than in Z-stabilizer; each data qubit serves as control and the ancilla serves as target;

Apply the final Hadamard gate before measurement;

Measure the ancilla qubit in the computational basis.

The combination of Hadamard gates transforms the Z-basis measurement into the X-basis measurement, enabling the detection of phase-flip errors. The measurement result indicates the parity of Z-errors across the four data qubits, which are involved in the stabilizer.

An important consideration in the design of the syndrome measurement circuit is to avoid hook errors. These occur when a gate error during syndrome extraction is propagated to multiple data qubits in a way that could cause a logical error even if the physical error could be corrected. The ZN rule specifies the optimal gate ordering to minimize hook error propagation [

14]. For Z-stabilizers, CNOT gates should be applied in a spatial pattern ordering that ensures that any two-qubit gate error affects data qubits in a correctable configuration. For X-stabilizers, the opposite ordering pattern is used to achieve the same error containment property. Our implementation follows the ZN rule through careful ordering in the

function, which determines the precise sequence in which CNOT gates are applied to each stabilizer’s associated data qubits.

To protect against syndrome measurement errors themselves, which can occur due to imperfect ancilla initialization, faulty gates, or measurement errors, surface codes perform T rounds of syndrome measurement, typically choosing a T value that is approximately equal to the code distance d. Each syndrome measurement round adds a temporal dimension to the error correction problem, transforming the two-dimensional spatial lattice into a three-dimensional spacetime syndrome graph with coordinates (x, y, t).

3.2. Error Decoding and Correction

The pattern of syndrome measurements extracted from quantum hardware is handed over to the decoder which must infer the most likely error configuration that produced that syndrome pattern. This decoding problem presents several fundamental challenges that make optimal solutions computationally intractable for large codes [

15]. Syndrome degeneracy is the occurrence that multiple distinct error patterns can produce similar syndrome measurements because errors that differ by a stabilizer operator are indistinguishable, creating an equivalence class of errors for each syndrome. Measurement errors add additional complexity because the measurement of the syndrome can contain some errors due to imperfect preparation of the ancilla state, faulty gates during the extraction of the syndrome, or faulty measurement bit flips. The computational complexity of optimal maximum-likelihood decoding is NP-hard in general, requiring exponential time to find the error configuration that maximizes the probability of producing the observed syndrome pattern.

The leading solution for decoding surface codes is based on minimum-weight perfect matching (MWPM), which maps the decoding problem onto a graph theory problem solvable in polynomial time using Edmond’s Blossom algorithm. The MWPM decoder constructs a three-dimensional syndrome graph where each node represents violated stabilizers at specific positions and times and edges that connect pairs of syndrome nodes which have weight proportional to the Manhattan distance between them in graph structure [

16]. On edges, lower weights correspond to more probable error paths because shorter paths require fewer individual qubit errors to produce the observed syndrome pattern. The matching algorithm pairs all syndrome nodes (including virtual boundary nodes) such that each node appears in exactly one pair and the total weight of all paired edges is minimized. Each pair represents an inferred error chain connecting two syndrome positions in space and time. For each matched pair of syndrome nodes, the decoder reconstructs the error chain by finding the shortest path connecting them in the underlying lattice, which defines the specific physical qubits where errors are inferred to have occurred. Correction of errors is determined by applying X gates to qubits in inferred X-errors and Z gates to qubits in inferred Z-error chains. The final step checks whether the total error chain, including the applied corrections, forms a non-trivial logical operator spanning the code. If not, the decoding succeeded in correcting the errors back to the codespace.

In this paper, we used the Blossom algorithm, which is implemented in the NetworkX graph library and solves the minimum-weight perfect matching problem in O() time where n represents the number of syndrome nodes detected. This polynomial-time complexity makes real-time decoding feasible even for moderately large surface codes. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the present implementation of the minimum-weight perfect matching (MWPM) decoder in Qrisp functions exclusively as an offline post-processing step. Although MWPM exhibits polynomial-time complexity, real-time syndrome decoding for surface codes of practical size often necessitates deployment on dedicated hardware accelerators such as FPGAs or ASICs due to strict latency constraints. In the current Qrisp–Qiskit–IQM execution stack, such integration is not supported, and all decoding is performed post hoc, following complete acquisition of the syndrome measurement data.

4. Implementation in Qrisp Environment

Surface codes were implemented in the Qrisp environment. Qrisp is a high-level quantum programming framework designed to make the development of quantum algorithms more accessible and intuitive while maintaining the performance necessary for quantum computing research [

17]. The framework enables algorithm design at a conceptual level similar to classical programming. Qrisp automatically compiles high-level operations into optimized quantum circuits at the gate level, handling resource allocation, qubit management, and circuit transpilation without requiring manual intervention from the programmer. Programs written in Qrisp can run on various backends, including local simulators, cloud-based simulators, and real quantum hardware, with minimal code changes, facilitating rapid testing and deployment across different platforms [

18]. Despite these high-level abstractions, Qrisp maintains competitive performance through sophisticated circuit optimization strategies including gate merging, circuit depth reduction, and intelligent qubit routing. In contrast, Qiskit is a well-established quantum computing software stack developed by IBM Research, providing detailed control over circuit construction, topology mapping, noise modeling, and hardware-specific optimizations. Whereas Qrisp abstracts much of the qubit-management and circuit-transpilation burden, Qiskit requires the practitioner to explicitly manage these steps, allowing more fine-grained tuning of gate schedules, routing, and error-correction primitives. This project selects Qrisp in order to prioritize developer productivity, modular architecture, and high-level algorithm design, while recognizing that a Qiskit-based implementation would offer deeper access to hardware constraints and error-correction frameworks at the cost of increased development complexity. This section presents the essential components of the implemented surface code pipeline. The full implementation can be accessed in a dedicated GitHub repository [

19].

4.1. Surface Code Construction

The core of the implementation is the

class, which manages the complete lifecycle of a distance

d surface code with

T syndrome measurement rounds. The class initialization accepts two parameters:

d specifying the code distance and

T specifying the number of syndrome measurement rounds to perform. Upon instantiation, the constructor allocates quantum resources by creating

QuantumBool objects for data qubits and

QuantumBool objects for ancilla qubits, storing these in class member arrays for later reference. A syndrome round counter

T is initialized to zero and will increase as the measurement rounds are executed. Two empty lists,

and

, are created to store measurement outcomes. The constructor then executes the syndrome measurement protocol by calling the

method

times with ancilla reset enabled, followed by one final syndrome measurement without reset and a complete readout of all data qubits. Qrisp’s QuantumBool type, which is used in implementation, provides automatic qubit management and seamless integration with Qrisp’s compilation infrastructure, which handles the translation from high-level quantum operations to low-level gate sequences [

20]. Reset of the ancilla between the rounds of the syndrome, implemented by reinitializing the QuantumBool objects of the ancilla, prevents measurement-induced error propagation that could corrupt subsequent extraction of the syndrome. The storage of the syndrome and final measurement outcomes in class members enables post-execution classical processing where syndrome patterns are analyzed by the decoder to infer and correct errors. The

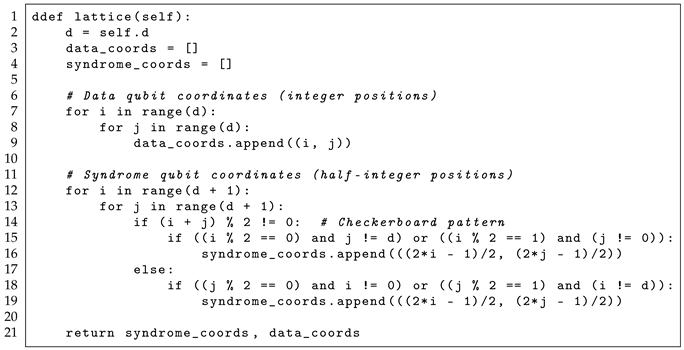

method presented in Listing 1 generates the two-dimensional coordinate system that defines the topological structure of the surface code, establishing precise spatial relationships between data qubits and syndrome measurement qubits.

| Listing 1. Creating lattice. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i001 Electronics 14 04707 i001]() |

Data qubits occupy integer coordinate positions that form a grid at locations (0,0), (0,1), …, (d−1, d−1), representing the physical qubit. Syndrome measurement qubits occupy half-integer coordinate positions at the centers of plaquettes and vertices of the dual lattice, with coordinates like (−0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 1.5), and so forth. This half-integer positioning geometrically represents that syndrome qubits measure stabilizers involving the four surrounding data qubits. The coordinate parity check % 2 implements a checkerboard pattern that alternates between the X-stabilizers and Z-stabilizers across the lattice. The conditional logic of nested loops handles boundary cases where syndrome qubits near the edges of the planar code connect to fewer than four data qubits. This coordinate system establishes the fundamental topological structure upon which all subsequent syndrome measurement operations are based.

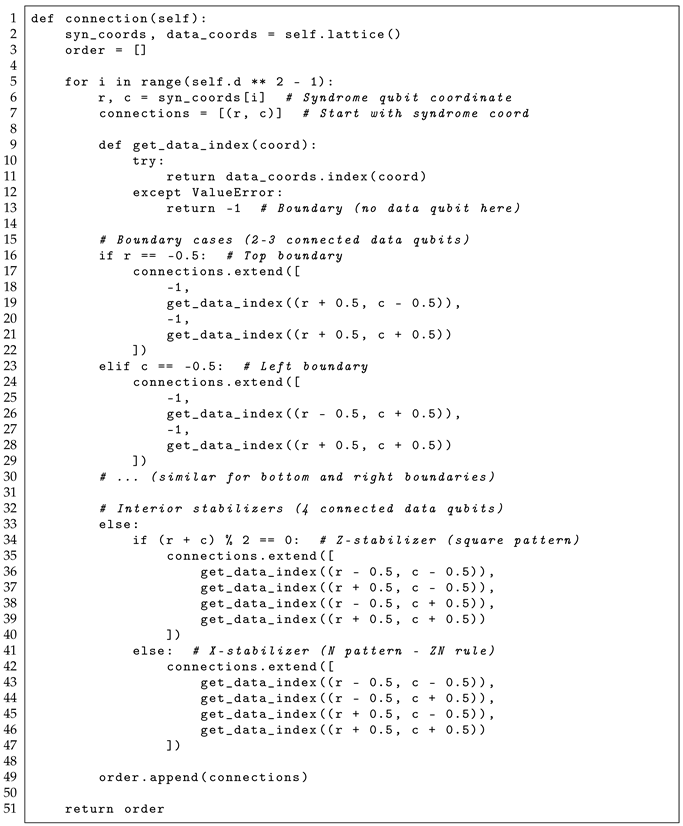

The

method presented in Listing 2 determines the precise mapping between the syndrome qubits and their associated data qubits, specifying which physical qubits participate in each stabilizer measurement. The second functionality of this function is to set the order in which the CNOT gates are applied to mitigate hook errors.

| Listing 2. Creating connection between qubits. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i002 Electronics 14 04707 i002]() |

4.2. Circuit Execution

The complete surface code execution involves T rounds of syndrome measurement followed by a final data qubit readout. Each syndrome measurement round detects errors that have occurred since the previous round, building a temporal history of error patterns across the spacetime lattice. The multi-round protocol enables detection of syndrome measurement errors by allowing the decoder to identify spurious syndrome violations that appear and disappear between consecutive rounds. In addition, it provides temporal information that enables the decoder to distinguish between different error histories that might produce similar final syndrome patterns.

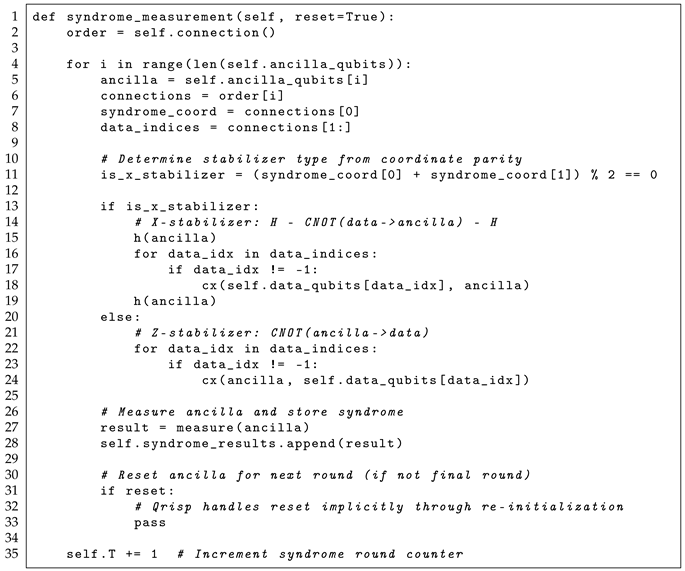

The

method presented in Listing 3 implements a single round of stabilizer measurements, executing the quantum circuit that entangles each ancilla qubit with its associated data qubits according to the connection map established earlier. The reset parameter controls whether the ancilla qubits are reset to |0⟩ after measurement, which is necessary between the syndrome rounds to prevent the measurement results of one round from influencing subsequent rounds.

| Listing 3. Measurement of syndromes. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i003 Electronics 14 04707 i003]() |

After all syndrome measurement rounds are complete, the method makes final measurements on all data qubits to determine the logical qubit state. This measurement projects the logical qubit into a definite computational basis state, providing the final output of the quantum computation. The readout iterates through all data qubits, applies measurement operations, and stores the results for subsequent classical post-processing. Combined with the accumulated syndrome data from previous rounds, these final measurements enable complete error reconstruction by the decoder.

4.3. Post-Processing

When the quantum circuit execution is complete and all measurements have been performed, the classical post-processing phase transforms the raw measurement into structured syndrome data suitable for error decoding. Transforming from quantum measurement outcomes to classical error correction algorithms involves careful parsing of measurement results to separate the final data readout from the syndrome history, temporal differencing to identify when and where errors occurred, and coordinate mapping to convert syndrome indices into positions in graph structure. The post-processing pipeline must organize the extracted information into data structures optimized for efficient graph-based decoding.

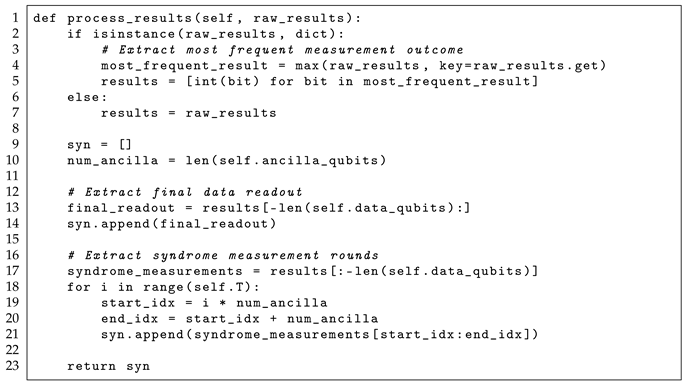

In Listing 4 the function

is presented. It serves as the central part between quantum measurement and classical decoding, accepting raw results from quantum circuit execution and restructuring them into an organized history of syndromes. The method first checks the result type and extracts the most frequently observed measurement outcome as representative chains of bits for analysis. This approach assumes that the most common measurement pattern is most likely to reflect the actual error configuration, though more sophisticated post-selection strategies could be applied for improved decoding performance.

| Listing 4. Process results. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i004 Electronics 14 04707 i004]() |

The core of the processing logic partitions the measurement bits into two components based on qubit allocation. The final bits correspond to the data qubit readout and are extracted from the end of the bits, forming the first element of the returned syndrome list. The remaining bits represent T rounds of syndrome measurements, with each round containing one bit for each ancilla qubit. The method segments this syndrome measurement region into T consecutive blocks, each of length , corresponding to sequential syndrome rounds. This temporal organization is crucial for the subsequent differencing operation that identifies when errors occur by detecting changes in the syndrome between rounds. The returned data structure is a list of rounds, where each element is itself a list of measurement bits, providing a hierarchical representation that mirrors the temporal structure of the quantum execution and facilitates intuitive indexing during decoding operations.

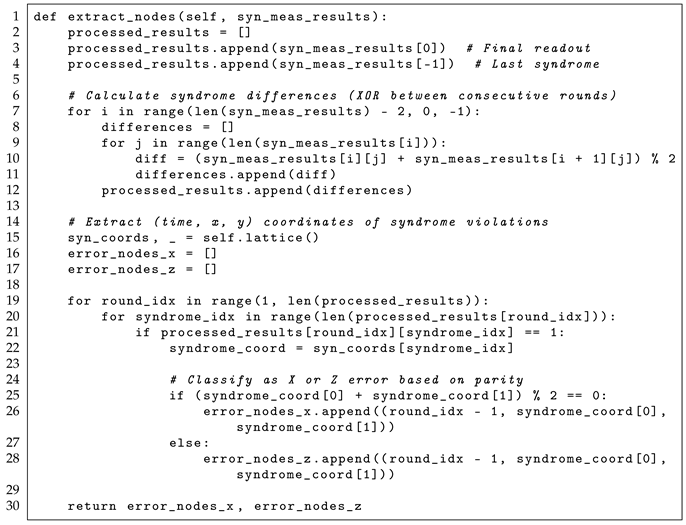

The method

—presented in Listing 5—implements the syndrome differencing algorithm that transforms temporally organized syndrome measurements into a set of coordinates representing where and when errors occurred. The decoder needs to know where errors happened; information is encoded in syndrome changes rather than absolute syndrome values. This means that when a stabilizer measurement flips from +1 to −1 or vice versa between consecutive rounds, it signals that an error occurred on one of the associated data qubits in the intervening time period. By computing the XOR of consecutive syndrome rounds, the method identifies these syndrome changes and maps them to specific spacetime locations where the decoder should infer error events.

| Listing 5. Extracting nodes. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i005 Electronics 14 04707 i005]() |

4.4. Graph-Based Decoder

The decoder is implemented in the class. It is made up of the MWPM algorithm using NetworkX graph data structures to solve the classical decoding problem. The decoder accepts parameters d, which is distance, T, which is a number of rounds of the syndrome, and an optional simulation flag. The constructor creates two separate NetworkX graph objects stored in a dictionary keyed by “X” and “Z”, enabling independent parallel decoding of bit-flip and phase-flip errors. The syndrome graph template is then constructed via , building the complete 3D structure that will be used for all subsequent decoding operations. This separation of X and Z error graphs, integration with NetworkX’s mature graph algorithms for shortest paths and matching, and explicit representation of virtual boundary nodes form the architectural foundation enabling efficient polynomial-time decoding.

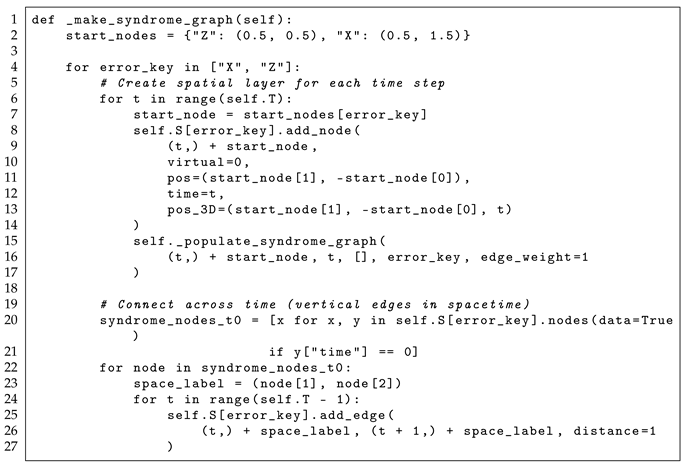

The method

presented in Listing 6 constructs a comprehensive three-dimensional graph in time that serves as a template for all subsequent decoding operations, representing every possible path an error chain could take through the spatial lattice over time. This graph is built once during decoder initialization and reused for all decoding tasks with the same code parameters, amortizing the construction cost across multiple circuit executions. The construction process operates independently for the X and Z error types, building separate graph structures that enable parallel decoding while maintaining the topological distinctions between bit-flip and phase-flip error chains.

| Listing 6. Creating graph. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i006 Electronics 14 04707 i006]() |

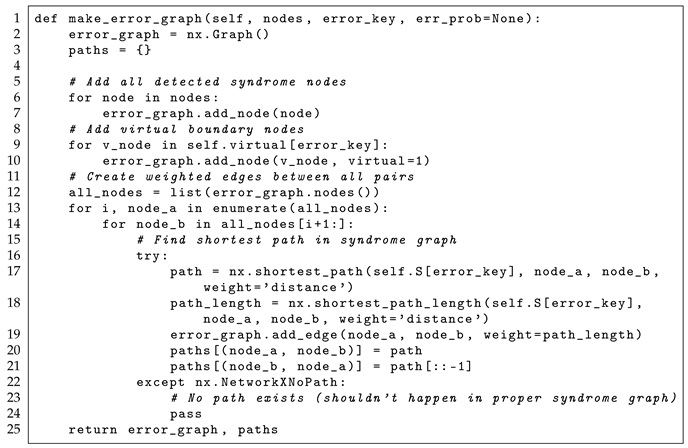

Another important method is which is presented in Listing 7. It transforms the list of detected error nodes into a complete weighted graph suitable for MWPM, where each pair of nodes is connected by an edge whose weight represents the most likely error path connecting them. Unlike the syndrome graph, which contains all possible syndrome positions across spacetime, the error graph is constructed dynamically for each decoding task and contains only the specific syndrome violations actually detected in the current measurement outcomes, plus the virtual boundary nodes that allow error chains to terminate at code boundaries. This problem-specific graph construction dramatically reduces the size of the matching problem from O() potential node pairs in the full syndrome graph to O() pairs where n is the actual number of detected syndromes, typically a small constant for low error rates.

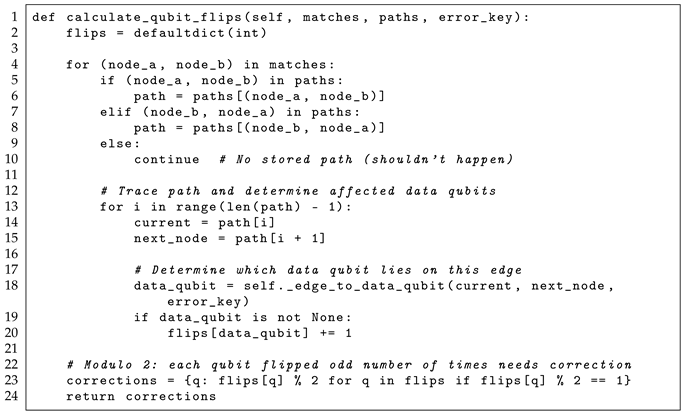

The method

presented in Listing 8 translates the abstract matching of the nodes of the syndrome into concrete corrections of the physical data qubits by tracing the shortest paths connecting matched pairs of syndromes and identifying which data qubits are included in those error chains. This reconstruction process maps the graph-theoretic matching solution back to the physical lattice, determining which qubits experienced errors and must be flipped to restore the encoded quantum state. The method handles the geometric intricacies of error chain overlap, where multiple inferred error paths may cross the same data qubit, requiring modulo-2 arithmetic to correctly determine the net correction needed.

| Listing 7. Creating error graph. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i007 Electronics 14 04707 i007]() |

| Listing 8. Calculate flips. |

![Electronics 14 04707 i008 Electronics 14 04707 i008]() |

The final step in the decoding pipeline combines X and Z corrections into net Pauli operators through the method. Since X and Z errors are decoded independently, some physical qubits may require both X and Z corrections, which, according to Pauli algebra, combine to form a Y correction (X·Z = iY up to a global phase). The method takes the separate X and Z correction dictionaries, identifies all qubits requiring any correction, and for each qubit determines whether it needs an X gate, Z gate, Y gate (if both X and Z corrections apply), or no correction. This produces a final correction operator that can be applied to the measured quantum state to recover the original encoded logical qubit value.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

This section presents a comprehensive experimental investigation of surface code quantum error correction implemented on real noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware using the developed Qrisp code. This study was aimed at evaluating the performance of the surface code pipeline on three IQM machines: Sirius, Garnet, and Emerald [

21]. In each of them, a series of runs with different distance and round parameters gives information about the performance and effectiveness of the algorithm. The results show the current state of practical quantum error correction and identify fundamental limitations that must be overcome to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation in the future.

This study involved 210,000 individual quantum circuit executions distributed in 21 different hardware configurations. Each configuration was tested with 10,000 measurement shots to achieve statistical significance. The implementation uses a Qrisp framework connected to the IQM cloud by an API, enabling direct execution on physical quantum processors without intermediate simulation layers.

5.1. Hardware

In this study, three IQM quantum processors were used to represent different ratios between system size and calibration quality [

21].

IQM Sirius operates as a 16-qubit machine with the Star24 architecture variant. Star24 includes star-shaped connectivity that naturally isolates qubits and reduces unwanted cross-talk. The processor demonstrates typical two-qubit gate fidelities in the range of 98–99%.

IQM Garnet expands the system to 20 physical qubits arranged in a square lattice geometry. This topology offers some advantages for surface code implementation, as the native 2D grid structure maps naturally to the lattice pattern. The square lattice provides nearest-neighbor connectivity that minimizes SWAP gate overhead while maintaining moderate cross-talk levels. On Garnet, as a mid-size processor, we can perform more complex runs than on Sirius. It allows us to use a distance d equal to three, which is impossible for Sirius due to the amount of physical qubits.

IQM Emerald represents the largest system that includes 54 physical qubits with a high-connectivity lattice topology. Expanding the qubit count theoretically enables larger code distances and more complex quantum algorithms, but this comes at the cost of increased calibration complexity. The size of it allows one to run with a distance d equal to five or by using a smaller distance with multiple rounds T.

The IQM–Qiskit stack does not expose calibration data (, , single- and two-qubit gate fidelities, or readout fidelities) at execution time. Nevertheless, the observed experimental behavior is consistent with the typical coherence and fidelity regimes reported for these processors in publicly available IQM technical documentation.

All processors contain the same fundamental native gate set, including the X, Z, RZ, and controlled-Z gates, which serves as the hardware-level basis on which all operations are compiled under the IQM standard instruction architecture. Circuit transpilation is performed using the Qiskit framework, which converts high-level Qrisp code into hardware-native gate sequences optimized for each processor’s specific topology and connectivity constraints [

22]. This uniform software interface enables direct performance comparison between platforms while addressing hardware-specific optimization.

The IQM architecture exhibits a critical limitation shared between all processors: the IQM–Qiskit transpilation stack does not support native qubit-reset operations. Traditional surface code implementations rely on a fast, deterministic reset to reuse ancilla qubits across all syndrome measurement rounds, thereby keeping the physical qubit overhead constant and enabling the construction of a compact space–time lattice. In our setting, the absence of such a reset forces each syndrome extraction round to be executed with a fresh set of ancilla qubits, causing the total qubit cost to scale as , where d denotes the code distance, and T is the number of rounds. This constraint significantly limits the accessible parameter space: experiments for , , and at larger values of T could not be executed, as the required number of physical qubits exceeds the capacity of the Sirius, Garnet, and Emerald processors. As a consequence, the temporal dimension of the surface code space–time structure cannot be collapsed onto a fixed ancilla layer, fundamentally differentiating this hardware-limited execution model from canonical surface code realizations.

5.2. Data and Metrics

The methodology employs a comprehensive suite of metrics to characterize the quantum circuit performance. These metrics collectively characterize the interplay between hardware noise, circuit complexity, and the error correction capability of the surface code pipeline.

Logical fidelity quantifies the probability that the measured logical state matches the intended encoded state. For the logical |0⟩ preparations that are used, this reduces to the frequency with which all data qubits are measured in the zero state. This raw fidelity reflects the combined impact of initialization, gate, measurement, and decoherence errors throughout circuit execution.

Shannon entropy quantifies the randomness of the measurement outcomes. For perfectly coherent quantum circuits with no errors, the entropy remains minimal. As circuits decohere under quantum noise, entropy increases toward the maximum value bits for n qubits. We observe entropy approaching this maximum for deep circuits, confirming complete loss of quantum information. The entropy growth rate with circuit depth directly indicates the strength of decoherence.

The number of unique measurement outcomes observed across 10,000 shots provides a discrete proxy for entropy, bounded above by the number of shots. Shallow circuits with low error rates produce a limited set of outcomes clustered around the ideal state. As errors accumulate with increasing depth, the measurement distribution broadens across state space until approaching uniformity, which means 10,000 states where each of them is observed once.

The circuit characteristics contain some data which include qubits used, circuit depth, and gate count. Circuit depth correlates directly with decoherence exposure, as each layer extends the window during which T1 and T2 processes degrade quantum information. The gate count scales approximately quadratically with depth due to stabilizer measurement patterns, with each additional round of syndromes requiring O() gates.

Error detection statistics from the decoding pipeline characterize the information available for error correction. X-type stabilizer violations indicate bit-flip errors that affect data qubits, while Z-type violations signal phase-flip errors. The distribution of X vs. Z errors underlying noise processes are typically asymmetric due to the differing physical mechanisms governing relaxation and dephasing. Our experiments observe a bias toward X-errors, consistent with IQM-reported coherence time hierarchy and measurement-induced state transitions.

The syndrome graph complexity metrics include node counts and edge counts, which are key aspects of the decoding algorithm. The number of nodes scale linearly with the product of distance and rounds, while the edges scale quadratically in the worst case. For the parameter ranges investigated, graph sizes remain comfortably within the tractable regime for polynomial-time MWPM algorithms.

5.3. Decoherence Evaluation

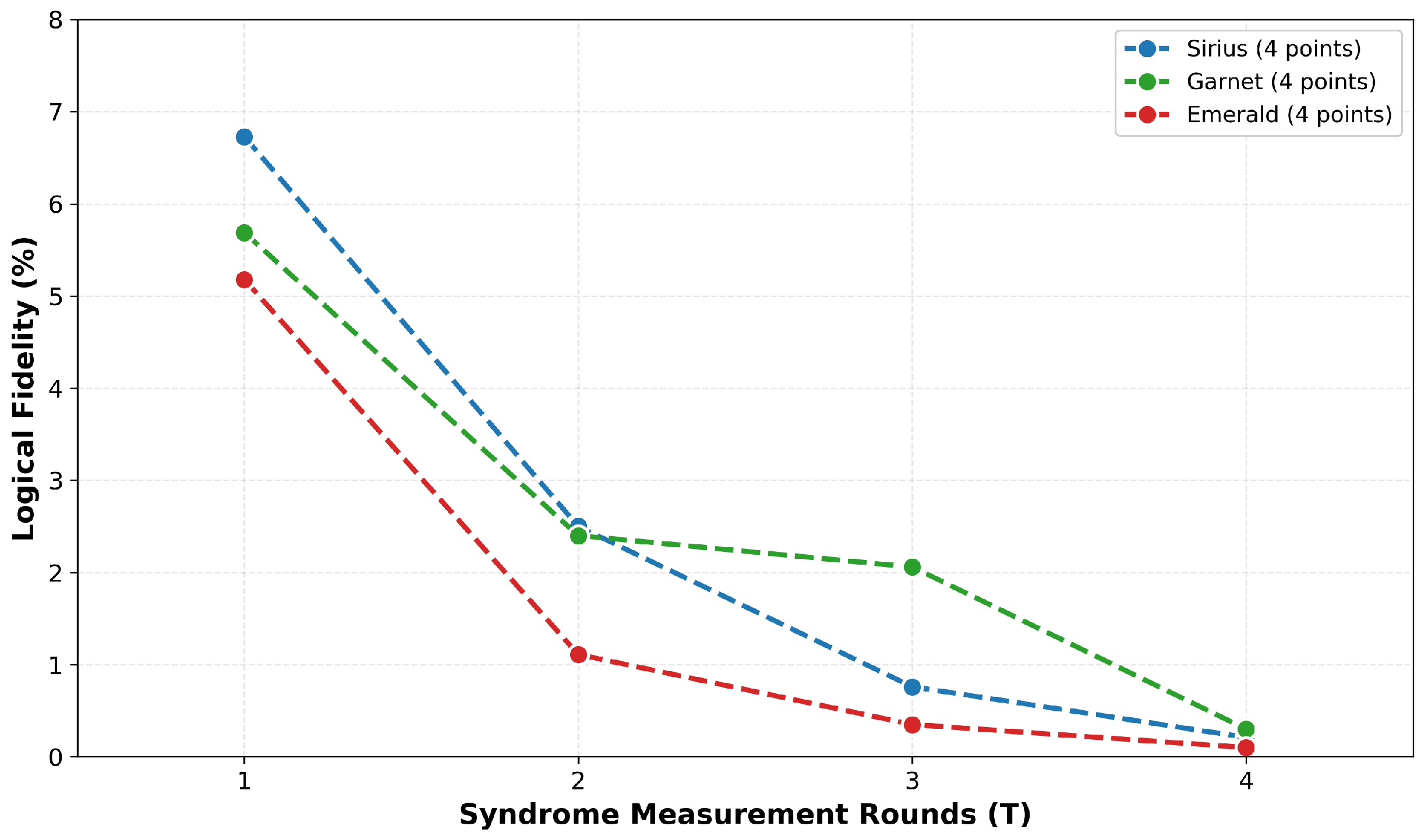

The initial experimental results reveal an exponential degradation of logical fidelity with the number of syndrome measurement rounds, as shown in

Figure 2. Fitting the decay model

to our data yields excellent agreement (

) for all three IQM machines, with decay constants

ranging from 0.68 (Garnet) to 1.12 (Emerald). The smallest system, Sirius (16 qubits), achieves the highest among tested devices but is still far below the threshold for fault tolerance fidelity of

at

, which decreases to

at

. In contrast, Emerald (54 qubits) shows lower initial fidelity (

) and faster decay (a

degradation), demonstrating counter-intuitive scaling behavior where larger quantum systems exhibit worse performance. This counter-intuitive outcome could result from several factors, including increased inter-qubit crosstalk in larger arrays, greater transpilation overhead due to connectivity constraints, and maintaining uniform calibration across many qubits. The exponential decay itself indicates that gate errors accumulate multiplicatively throughout the syndrome rounds, each measurement introducing approximately 40–60% error probability. These results confirm that current NISQ hardware operates far below the fault tolerance threshold, where physical error rates (∼3% per gate) exceed the theoretical threshold (∼0.1–1%) by roughly an order of magnitude.

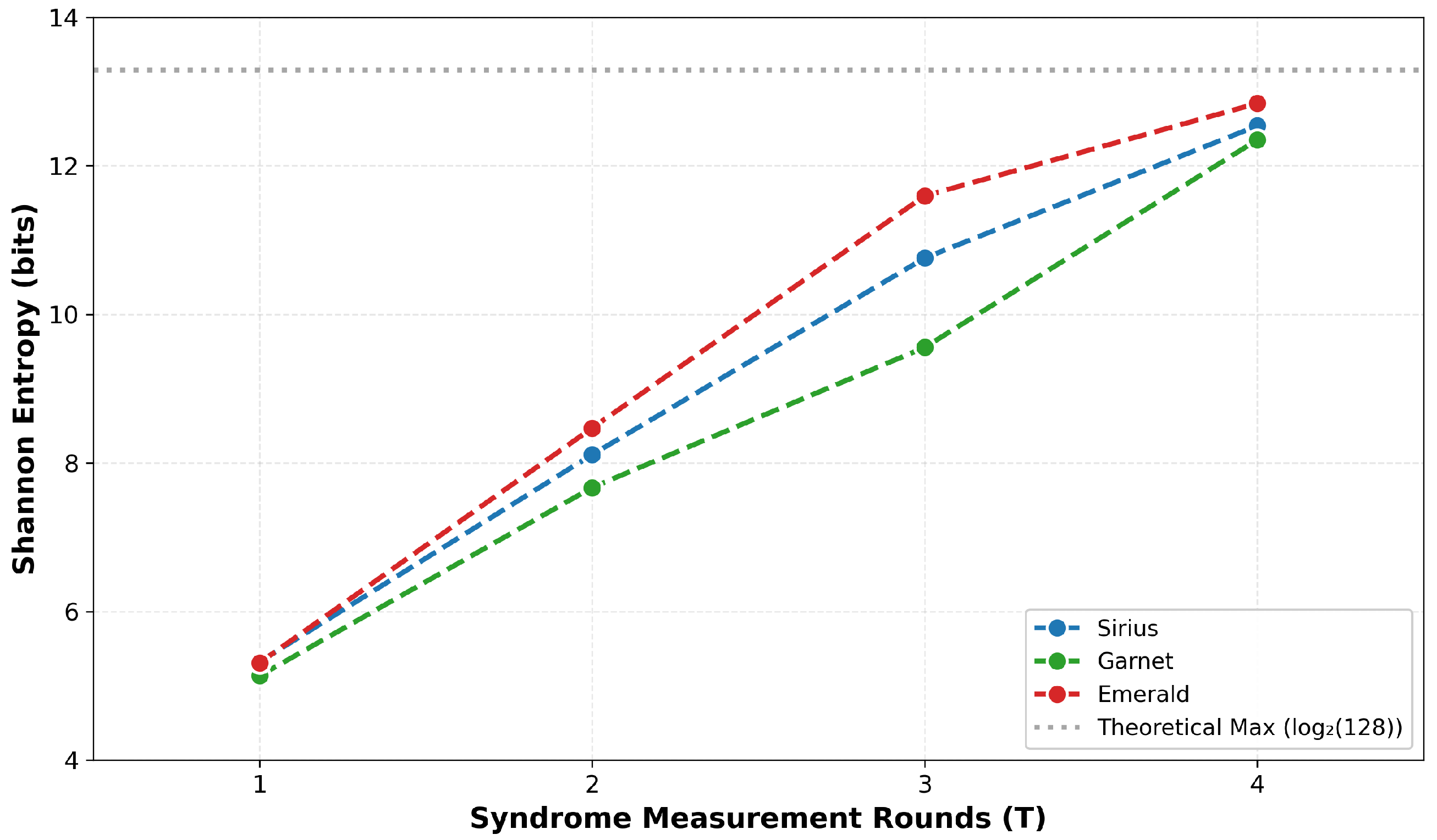

Figure 3 shows the loss of quantum coherence through Shannon entropy analysis. The entropy

increases from approximately 5.2 bits at

to 12.5 bits at

, asymptotically approaching the theoretical maximum of 13.29 bits (

) for a 7-qubit system. This growth is remarkably consistent across all three IQM machines, clearly showing that this is independent of the specific hardware architecture.

At , the entropy of ∼5.2 bits indicates that the measurement results have a significant structure, which means that approximately dominant states carry most of the probability mass. By , the entropy of ∼12.5 bits corresponds to effectively populated states (approx. 5800), indicating a near-uniform distribution over the available Hilbert space. The minimum-weight perfect matching decoder requires correlated syndrome patterns to infer error locations, but in a maximally entropic state, syndromes become statistically independent noise rather than informative signals. The physical mechanism underlying this entropy growth is the accumulation of decoherence through amplitude damping and phase damping processes during the multi-round syndrome measurement protocol.

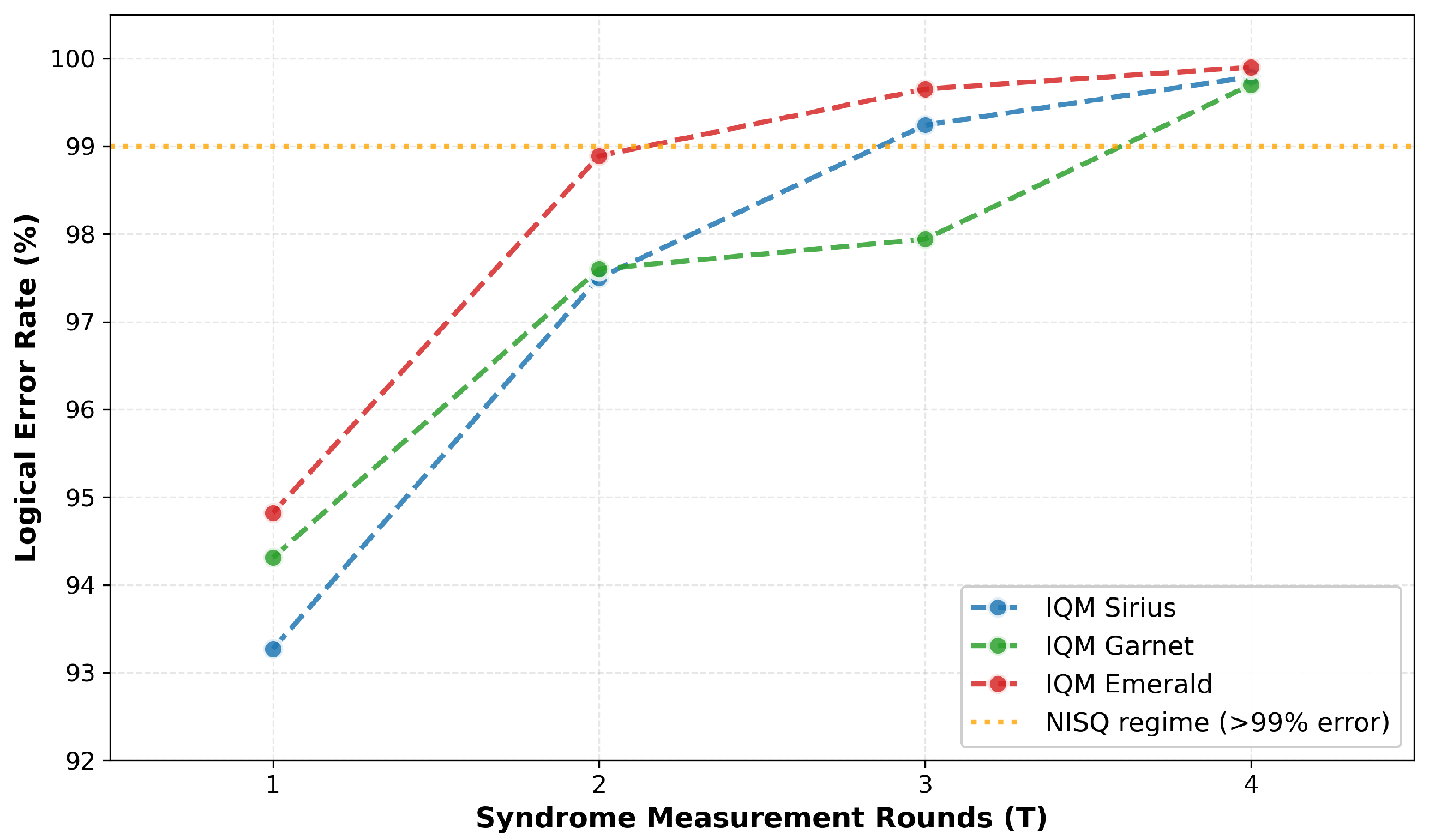

5.4. Error Correction

Figure 4 clearly shows the fundamental challenge facing quantum error correction on currently available hardware. Logical error rates increase from 93–95% at

to 99.7–99.9% at

, approaching complete randomization. This growth directly contradicts the fault-tolerant computing paradigm, where error rates should decrease with additional syndrome measurements.

The root cause is operating in the sub-threshold regime. The surface code theory predicts exponential error suppression only when the physical error rate p falls below a threshold – that depends on the error model and decoder. The hardware shows the physical gate error rate , measurement error rate –, and the surface code threshold – for perfect minimum-weight matching. With –6, the operations are above the threshold where each error correction attempt introduces more errors than it corrects. Formally, the effective logical error rate scales as approximately rounds. For , , and , the effective logical error rate is about (capped at 1.0), which is explained by the observed near-complete failure.

The universality of this behavior across all three machines—despite their architectural differences, indicates that it is a hardware generation issue rather than machine-specific artifacts. Achieving fault-tolerant quantum error correction requires order-of-magnitude improvements in physical error rates.

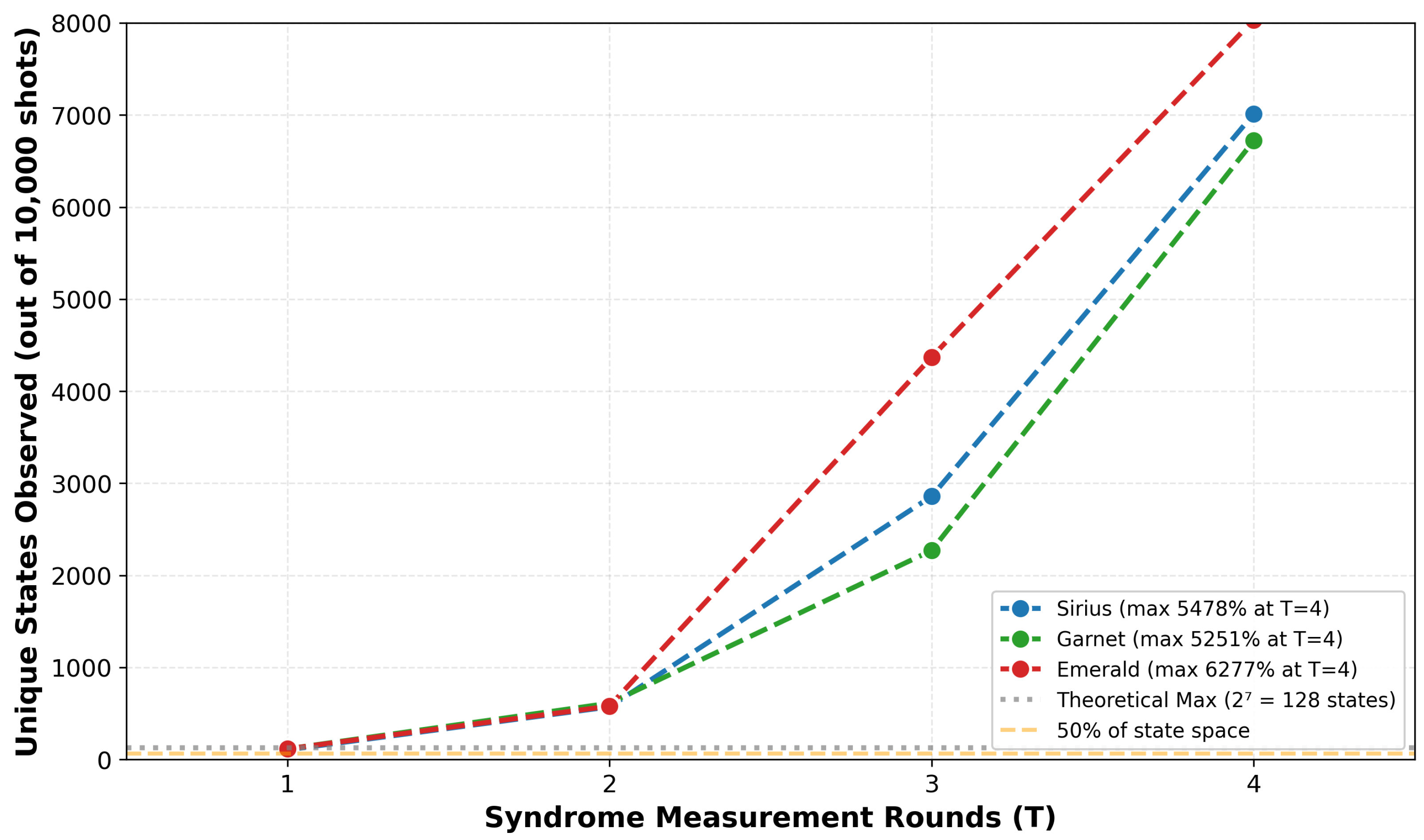

Figure 5 visualizes the progressive randomization of the quantum state through the unique state metric observed in 10,000 shot runs. For

, which is equal to 7 qubits, the Hilbert space contains

possible computational basis states. Ideally, encoding the logical |0⟩ should concentrate the measurements in a small subset of states corresponding to the code subspace and correctable error patterns. However, the observations are different.

For T = 1: unique states were observed (82–90% of maximum) Average occupation: shots per state. Interpretation: Significant structure remains.

For T = 4: approx. 7000 unique states observed (55 of 128 basis states) Average occupation: shots per state. Interpretation: Near-uniform exploration of state space.

This state space explosion demonstrates the fundamental problem: the measurement distribution becomes so diffuse that individual states carry a negligible probability mass. For the MWPM decoder to function, it requires syndrome patterns that occur with sufficient frequency (>1% each), error chains with different syndrome signatures, and statistical power to identify minimum-weight matching. Compared with theoretical expectations, for an ideal surface code with physical error rate, we expect dominant states carrying more than 95% of probability mass. The 500-fold discrepancy in state diversity quantifies the gap between the real hardware and fault-tolerant requirements.

5.5. Algorithm Performance

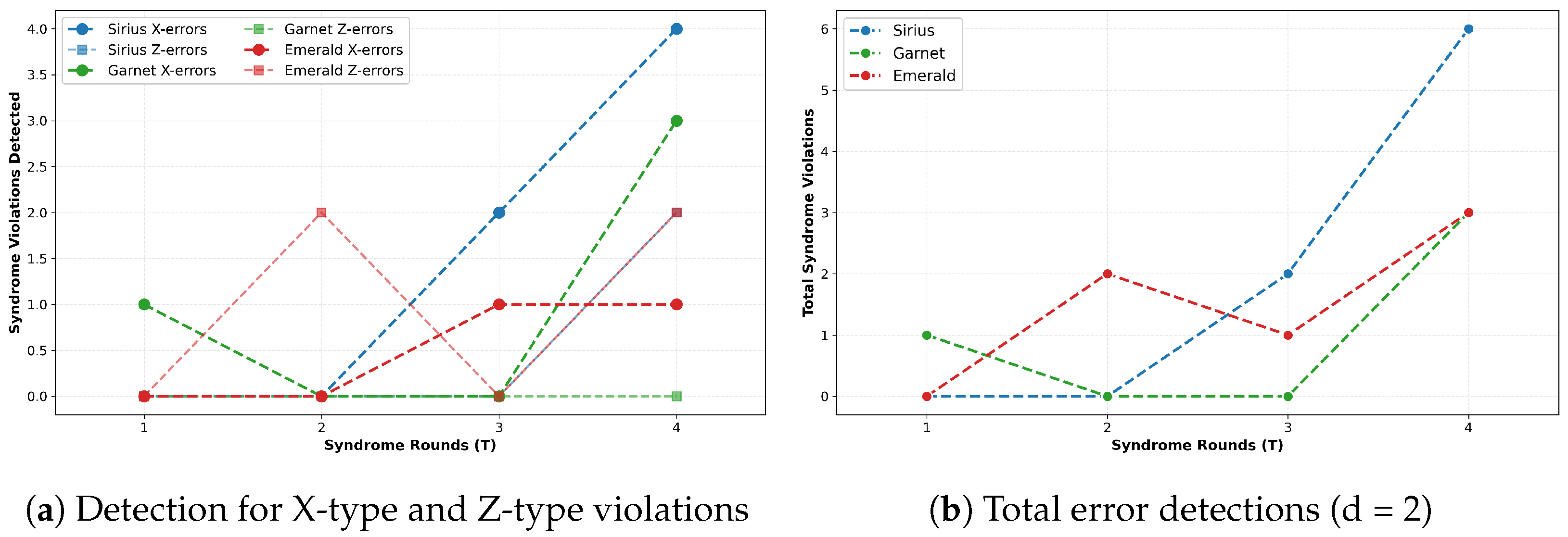

Figure 6 validates the error detection component of our quantum error correction pipeline. The pipeline successfully identifies syndrome violations—indicators of quantum errors—through stabilizer measurements. In particular,

Figure 6a distinguishes between bit-flip and phase-flip errors, showing that both error channels are independently monitored. Across all three machines, syndrome violations increase with syndrome rounds: from 0–1 detections at

to 3–6 at

. This scaling is expected—more complex circuits accumulate more errors, leading to more stabilizer violations. Notably, X-type errors slightly dominate Z-type errors in most configurations, suggesting that bit-flip processes are more frequent than pure dephasing on IQM hardware.

The successful detection of syndromes demonstrates that implementation correctly executes stabilizer measurements via ancilla qubits, extracts syndrome patterns from measurement outcomes, and identifies spatial and temporal error locations. This confirms the first critical stage of quantum error correction, namely error detection, even though the subsequent correction stage is unable to compensate for the high physical error rates. The consistency of syndrome detection across machines indicates that the algorithm is hardware-independent at the logical level, with differences arising solely from physical error rates rather than implementation details.

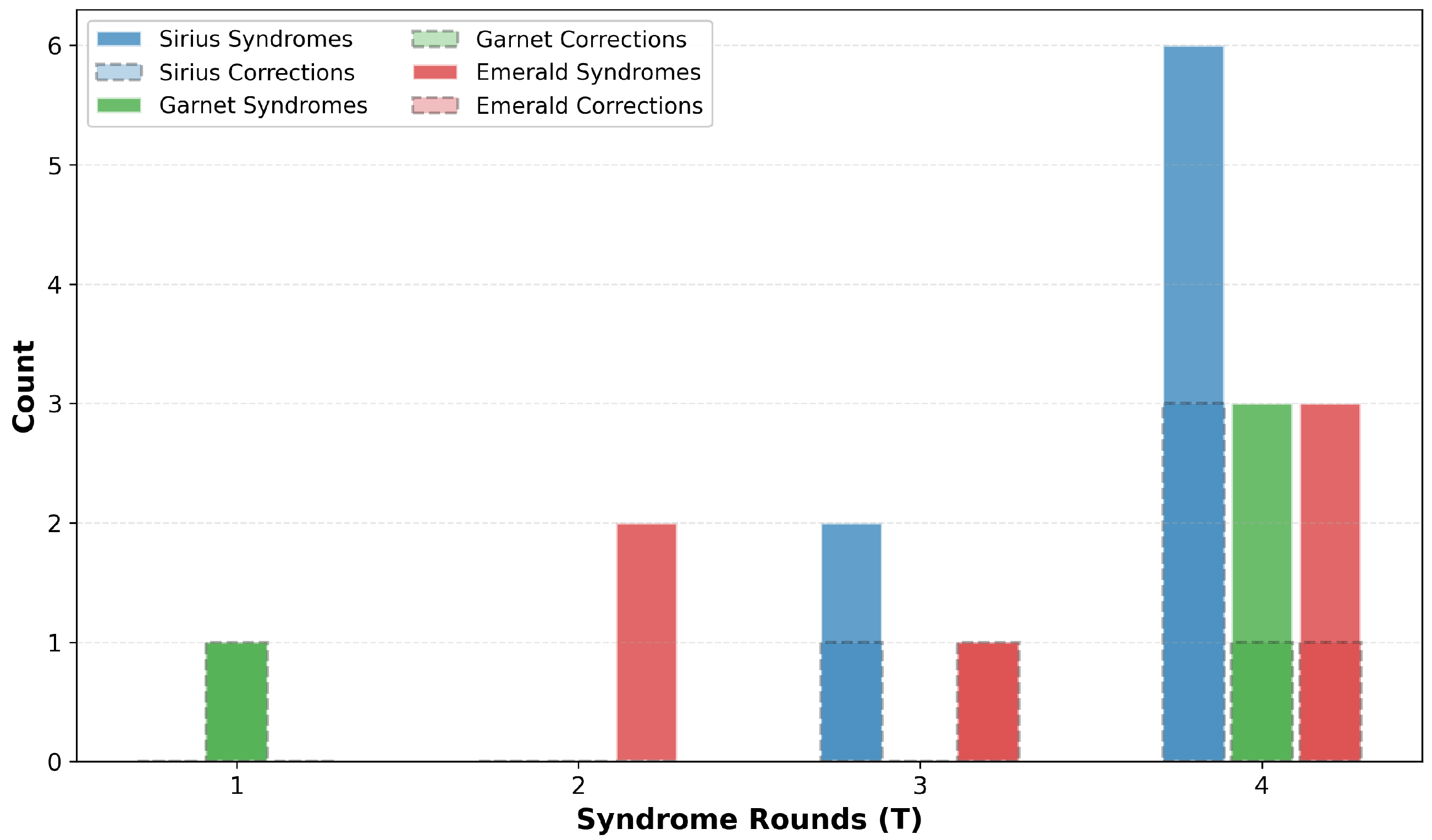

Figure 7 quantifies the performance of our minimum-weight perfect matching (MWPM) decoder—the core algorithmic component responsible for inferring error locations from syndrome measurements. For each configuration, the number of syndrome violations detected is compared with the number of Pauli correction operators computed. The decoder achieves an average correction efficiency of approximately 50%, which means that roughly half of the detected syndrome violations result in proposed correction operations. This ratio is characteristic of MWPM decoding: not every syndrome defect requires a correction—some defects pair with each other or with boundary nodes in the matching graph, resulting in error chains that cancel or loop back.

The successful computation of correction operators across all machines and syndrome rounds validates several critical algorithmic components.

Spacetime graph construction: converting syndromes into nodes on a 3D lattice (space × time).

Matching graph generation: building weighted graphs with edge costs representing error probabilities.

MWPM solution: finding minimum-weight perfect matching to identify most likely error chains.

Pauli operator determination: translating matched paths into specific X and Z correction operators on data qubits.

The increase in absolute counts with the rounds of the syndrome reflects the accumulation of errors in longer circuits. However, this growth ultimately overwhelms the correction capability; while the decoder correctly identifies what should be corrected, applying these corrections cannot overcome the approx. 3% per-gate error rate, explaining the continued degradation of fidelity. Importantly, the algorithm’s operational success on real hardware—despite poor final fidelity—demonstrates that the implementation is correct and that poor performance stems from physical error rates exceeding the fault-tolerant threshold, not from software bugs.

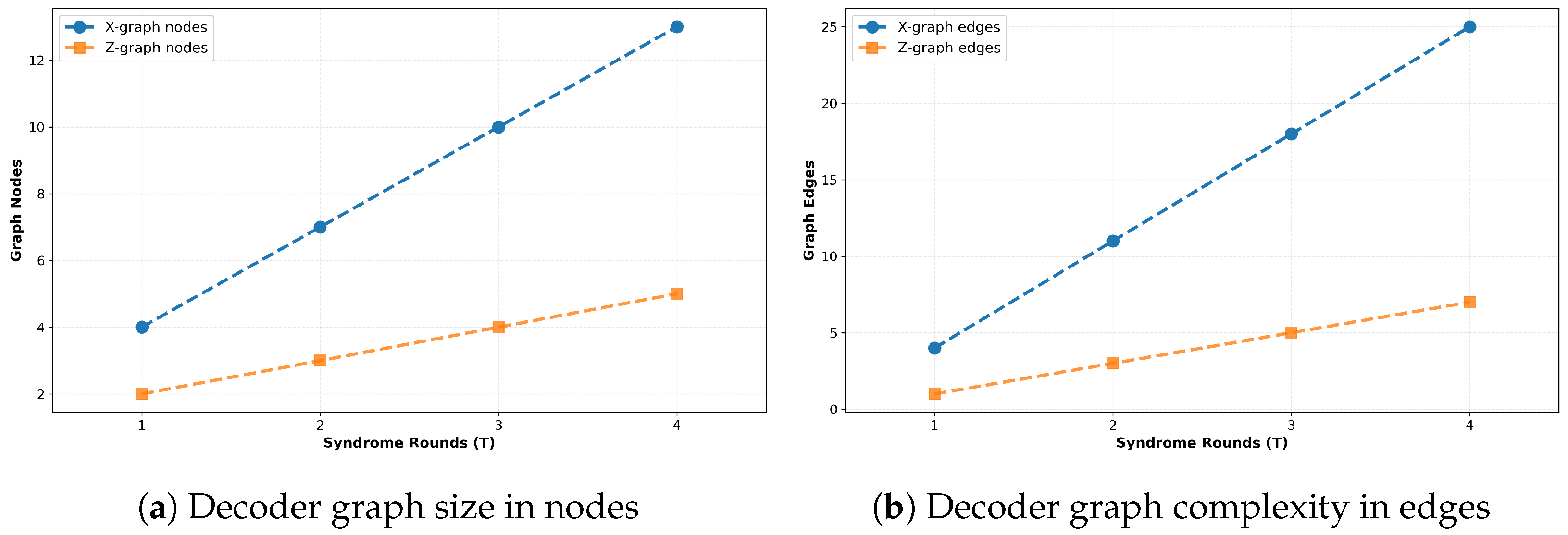

Figure 8 analyzes the computational complexity of the MWPM decoding problem through the lens of the matching graphs constructed from the measurements of the syndrome. For each configuration, we track the number of nodes (syndrome defect locations plus boundary anchor points) and edges (weighted connections representing possible error chains) in both the X-type and Z-type matching graphs.

The results demonstrate approximately linear growth with syndrome rounds:

X-graph nodes: 4 () to 13 ();

Z-graph nodes: 2 () to 5 ();

X-graph edges: 4 () to 25 ();

Z-graph edges: 1 () to 7 ().

The superlinear growth of the edges relative to the nodes is expected from graph theory—in a complete or near-complete graph, the edges scale as where n is the number of nodes. This quadratic scaling impacts the runtime of MWPM, as the minimum-weight perfect matching problem has complexity using Edmonds’ blossom algorithm. To assess the practical feasibility of decoding within the Qrisp-based surface code pipeline, we evaluated the computational overhead associated with the minimum-weight perfect matching (MWPM) decoder used in this work. Graph construction and matching were performed using the NetworkX implementation of the Blossom algorithm, whose asymptotic scaling of in the number of syndrome nodes n provides a well-understood upper bound on classical runtime. In all configurations tested here, including the largest instances corresponding to code distances up to and multiple rounds of syndrome extraction, decoding consistently completed well below one second on a standard workstation-class CPU. The memory footprint of the decoder remained modest, as the size of the syndrome graph grows quadratically with both the number of temporal rounds and the number of spatial stabilizers. Throughout all experiments, classical processing never constituted a bottleneck: the end-to-end latency of the MWPM decoder remained significantly below the wall-clock execution time of quantum jobs on the IQM hardware. These observations are in line with prior reports on software-based surface code decoding and confirm that offline MWPM decoding is computationally efficient for the system sizes investigated in this study.

X-type graphs are consistently between two and three times larger than Z-type graphs because the surface code has more X-stabilizers than Z-stabilizers (3 vs. 1 for the minimal planar code), leading to more potential bit-flip error chains to consider.

The perfect alignment of the curves on all three machines confirms that the complexity of the graph is purely a function of the parameters of the surface code () and the results of the syndrome, not the physical implementation. This hardware independence validates our implementation: the same logical algorithm produces the same computational problem regardless of which quantum computer executes the circuit.

From a practical standpoint, the linear-to-quadratic scaling suggests that decoder runtime will grow significantly for larger codes and more syndrome rounds. For and , we would expect graphs with hundreds of nodes and thousands of edges, making real-time decoding increasingly challenging. This motivates research into approximate or heuristic decoders that trade optimality for speed.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented an experimental investigation of surface code quantum error correction algorithms implemented in the Qrisp framework and tested on three IQM processors, spanning 21 hardware configurations and analyzing 210,000 quantum circuit executions. The systematic exploration of the parameter space defined by the code distance (d from 2 to 5) and the syndrome measurement rounds (T from 1 to 4) leads to the characterization of the current error correction capabilities, the identification of fundamental limitations, and the discovery of a scaling problem.

The successful implementation and validation of a complete surface code error correction pipeline on quantum hardware were demonstrated. This pipeline contains logical qubit encoding through stabilizer checks, temporal syndrome measurement across multiple rounds, spacetime syndrome graph construction, MWPM decoding, and correction proposal calculation. The execution on Sirius, Garnet, and Emerald quantum processors demonstrated operation of the algorithm in various hardware architectures. The modular implementation in the Qrisp framework establishes a basis for future error correction research, easily adaptable to improved hardware as gate fidelities advance.

Experimental validation on IQM quantum processors reveals that current NISQ hardware operates far from the fault-tolerant regime required for effective quantum error correction. The measured logical fidelities across all tested configurations remain below 6.4%, with corresponding error rates spanning 93.6–99.9%—significantly above the theoretical threshold of less than 1% needed for scalable quantum computing. Hardware comparison across three IQM processors reveals that qubit count alone does not guarantee performance.

Moreover, the Qrisp implementation demonstrated the possibility of high-level quantum programming frameworks for advanced quantum algorithms including error correction, contrasting with traditional low-level approaches that use Qiskit directly. Qrisp’s abstraction layers reduce implementation complexity while maintaining full access to hardware features. The developed open-source codebase offers future researchers a ready-to-use surface code implementation, thereby obviating the need to reconstruct fundamental error correction routines.