1. Introduction

The architecture of modern software systems is increasingly characterized by the integration of data-driven, intelligent components with traditional software modules. These intelligent components, often fundamentally modeled by Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), are primarily responsible for complex decision-making tasks. This hybrid design endows systems with a significant advantage: the capacity to learn from new requirements and dynamically adapt to evolving environmental conditions. Consequently, such systems are now pivotal in a wide array of domains, including autonomous robotics, unmanned aerial vehicles, and intelligent manufacturing, where runtime decision-making is critical.

The performance and reliability of these composite systems are inherently dependent on the quality of their intelligent core. As the primary decision-making entity, the behavior of an ANN component directly influences the overall system behavior. However, the quality of an ANN is not determined by static, human-defined logic but is instead highly contingent upon the data used for its training. Therefore, deficiencies within the training data (i.e., deficient data), such as inaccuracies, noise, mislabeling or a lack of representativeness, can severely degrade the ANN’s performance. Crucially, it is these very training samples that, when used to train neural network components, can lead to system-level property violations even when the network meets traditional accuracy metrics. This phenomenon specifically refers to data that induces incorrect decision boundaries in critical regions of the input space. When a compromised ANN is embedded within a larger system, these performance deficits propagate, ultimately leading to erroneous or sub-optimal decisions at the system level.

The challenge of mitigating data-centric deficiencies is compounded by the inherent difficulties in their detection. This problem manifests in two primary phases of the ANN lifecycle. First, during the training phase, the selection of appropriate data is largely guided by human expertise, with no established standard to definitively ascertain the suitability of a given dataset. Second, the testing and validation paradigm for ANNs diverges fundamentally from that of traditional software. In conventional software testing, outputs are expected to match specified requirements exactly. In contrast, ANN testing involves adjusting model parameters until the discrepancy between actual and expected outputs falls within an acceptable, often statistically defined, range. This inherent acceptance of uncertainty during validation means that latent data flaws can remain undetected.

Ultimately, this uncertainty is not contained within the ANN but is passed on to the traditional software components that depend on its outputs. This propagation creates a critical challenge for system reliability and debugging, as it becomes exceptionally difficult to trace faulty system-level behavior back to its root cause in deficient training data.

To address this fundamental challenge, this paper proposes a verification-based method that systematically traces system-level property violations back to specific deficiencies in training data. Our methodology follows three key phases: (1) constructing a unified system model integrating both conventional components and neural networks; (2) extracting interpretable fuzzy rules from the neural network to bridge the semantic gap between data-driven computation and formal reasoning; and (3) applying model checking to verify system properties. When property violations are detected, they are mapped back through the corresponding fuzzy rules to precisely identify the responsible data samples via a novel inverse mapping technique. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first work that enables formal tracing from system-level anomalies to data deficiencies through model verification. Given its foundation in general ANN architectures, the proposed method shows significant potential for extension to other AI paradigms.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

A novel framework that formally links system property violations to specific training data deficiencies;

An integrated approach combining fuzzy rule extraction with model checking; and

The first application of model verification for data deficiency tracing.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in the field.

Section 3 presents our proposed methodology for deficient data detection based on model verification.

Section 4 demonstrates the application of this methodology through a case study on deficient data tracing in manufacturing systems. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses potential future research directions

2. Related Work

2.1. Learning-Based Approaches for Detecting Deficient Data

To cope with the deficient data manually identified, some approaches [

1,

2,

3,

4] are proposed, sucha as uncertainty quantification, few-Shot learning, feature fusion, unsupervised Learning, and physics-informed fusion. For example, in a driving behavior segmentation task, Liu et al. [

2] showed that a feature extraction method based on a deep sparse autoencoder with fixed point (DSAE-FP) could reduce the negative effect of defective data. In predicting the health of components in an automobile, Shekar et al. [

3] proposed a data augmentation approach that replaces random attributes in the dataset with noise. By training the models with certain levels of noise, the new approach enhances the robustness against sensor failures in the real world. To deal with the incomplete and imbalanced data collected in the real production through the industry wireless sensor network, Zhou and Yu [

4] presented a solution, in which the K Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm is applied to do missing value imputation and the Adaptive Synthetic Sampling algorithm is utilized to generate a balanced dataset. To tackle scarce annotations and unreliable predictions in defect segmentation, Yu et al. [

5] developed a risk-aware framework using a Bayesian U-Net. The system employs an uncertainty-error loss function for self-assessment and integrates active learning to seek expert input when confidence is low, enabling continuous model improvement. F2MCANet [

6] addressed surface defect recognition with limited samples through a multi-channel attention module that combines global and local features. Its frequency fusion module captures both semantic and texture information, maximizing data utilization efficiency. The PAWS method [

7] incorporated physical priors into weakly supervised anomaly detection, significantly improving sensitivity to rare signals and performance in high-noise environments while maintaining model flexibility and supervised-method effectiveness.

These methods are probabilistic, not deterministic. This means they cannot offer definitive proofs, only guesses about potential defects. Their results depend on their training data, leading to risks of false alarms and missed defects, and they cannot reliably check complex business rules. In contrast, formal methods use mathematical logic to define strict data rules (e.g., business specifications), allowing for complete dataset verification. Their key strength is provable precision—if the rules are correct, they can find every single violation with minimal false positives, stopping errors at the source. This provides a level of certainty for critical systems that traditional, statistics-based methods cannot, turning data quality from a guessing game into a verifiable process.

2.2. Hybrid Modeling with Petri Nets and Neural Networks

The recent research trend focuses on a deep integration of Petri nets and neural networks to create unified, intelligent modeling frameworks. Ahson [

8] utilized basic Petri net concepts to develop multi-layered, distributed intelligence architectures resembling Artificial Neural Networks, defining a new class of Fuzzy Neural Petri Nets (FNPNs) for representing fuzzy knowledge bases and performing reasoning under uncertainty. Petrosov et al. [

9] proposed using an Artificial Neural Network to dynamically control Genetic Algorithm (GA) parameters, employing the Theory of Petri Nets as a unified mathematical apparatus to model the integrated operation of the GA and ANN. Albuquerque et al. [

10] introduced a novel fully adaptive Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) modeled with Hierarchical Timed Colored Petri Nets (HTCPNs), which was capable of being trained by the backpropagation algorithm and demonstrated performance comparable to standard implementations on benchmark tasks. Kaid et al. [

11] developed a hybrid deadlock control strategy for Automated Manufacturing Systems (AMSs) that integrated a neural network with a Colored Petri Net (CPN) model for fault detection and treatment, combining the modular advantages of Petri nets with neural network learning, and later further integrated Colored Resource-Oriented Timed Petri Nets (CROTPNs) with Neural Networks for deadlock control and fault diagnosis in Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems (RMSs) [

12], demonstrating superior performance in throughput and resource utilization. De Oliveira et al. [

13] explored the use of Coloured Petri Nets to model MLP networks to enhance interpretability, introducing a structured methodology with a weight propagation matrix and validating it with a COVID-19 classification case study. Hanna et al. [

14] combined Fuzzy Petri Net (FPN) and Neural Network (NN) in an intelligent quality control architecture for a CNC-milling centre, where the FPN processed fuzzy inputs to determine surface roughness and an NN verified and predicted the results. Finally, Jitmit and Vatanawood [

15] proposed a systematic scheme for converting a backpropagation ANN into a reusable Hierarchical Coloured Petri Net module, demonstrating its application with the XOR problem.

Despite their aim to solve practical challenges in complex systems through the fusion of formal and data-driven models, the aforementioned studies fail to adequately address the detection and processing of defective data used for model construction.

3. Model Verification-Based Methodology for Deficient Data Detection

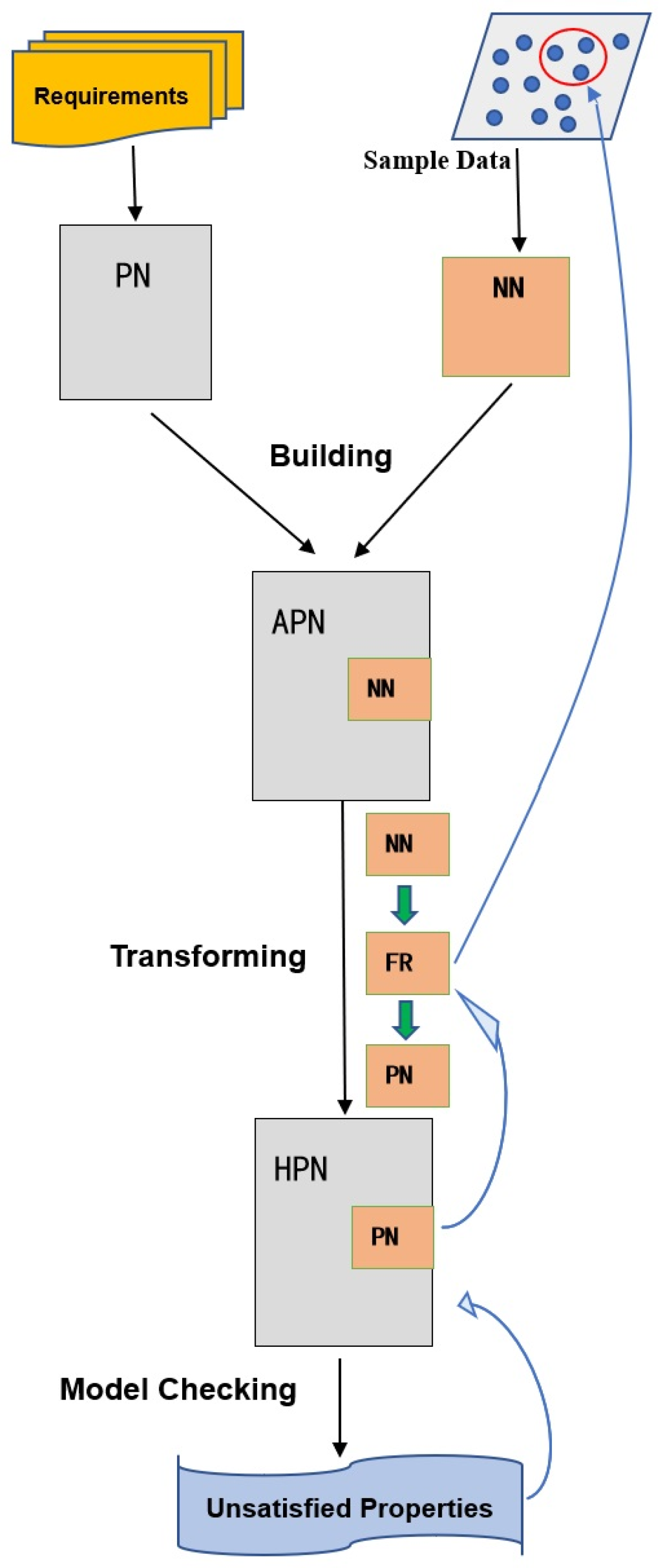

The overall framework of our proposed

approach, depicted in

Figure 1, follows a coherent analytical pipeline that begins with the construction of a unified system model from both software requirements and sample data. Components with explicit behavior scenarios are formally captured using Petri Nets (PNs), while those characterized solely by input–output relationships are modeled via Neural Networks (NNs). These elements are integrated into an Adaptive Petri Net (APN), which extends conventional Petri Nets through the introduction of neural network-based A-transitions to represent learning and adaptive behavior. To enable formal verification, the Adaptive Petri Net is subsequently transformed into a Hybrid Petri Net (HPN), making it amenable to analysis by the KeYmaera prover—a specialized tool for hybrid systems. Through model checking, system properties are rigorously verified, and any violations are systematically traced back to fuzzy rules extracted from the neural component. Finally, a novel inverse mapping mechanism links these rules to specific subsets of the training data, thereby identifying the deficient samples responsible for the observed anomalies.

3.1. Construction of the Adaptive Petri Net Model

To establish a unified formal foundation for modeling both conventional software components and neural network-based intelligent components, we introduce the Adaptive Petri Net as our primary modeling formalism.

3.1.1. Adaptive Petri Net

The Adaptive Petri Net extends the classical Hybrid Petri Net framework by incorporating specialized transitions that embed neural network functionalities, enabling the representation of learning and adaptive behaviors within a rigorous semantic structure.

According to the definition from the study [

16], an

Adaptive Petri Net is formally defined as a subclass of Petri net

that comprises three fundamental components:

A set of closed process nets ;

A set of closed learning process nets ; and

A set of Rendezvous communication mechanisms .

These components are constrained by the following conditions:

Structurally, an Adaptive Petri Net integrates several key elements that enable its adaptive capabilities. The framework incorporates both discrete and continuous components, where discrete places (D-places) and transitions (D-transitions) model the system’s logical states, while continuous places (C-places) and transitions (C-transitions) capture the dynamics of the environment. Central to its adaptability are the adaptive transitions (A-transitions), which are special transitions that encapsulate neural network sub-models, thereby enabling data-driven decision-making within the net’s execution flow.

3.1.2. Model Construction Methodology

The construction of an Adaptive Petri Net from hybrid software requirements follows a systematic integration process:

The first step: Deterministic Component Modeling. For requirements with well-defined behavioral scenarios, we apply the automated approach by Ding et al. [

17] to extract regular Petri net models from textual specifications. This generates the foundational

D-places,

D-transitions, and their connectivity patterns.

The second step: Neural Component Extraction. For data-driven requirements characterized by input–output relationships, we train three-layer backpropagation neural networks on available sample data. The trained networks are mapped to A-transitions, with input and output layers connected to corresponding C-places representing continuous variables.

The third step: Model Integration. The deterministic and neural components are integrated by establishing connections through interface places based on the captured boundary dependencies. The integration ensures the following:

Data flow between conventional and neural components maintains type consistency.

Temporal dependencies are preserved through appropriate place-transition connectivity.

The composite model maintains the liveness and boundedness properties of the constituent subnets.

This structured construction approach ensures that the resulting Adaptive Petri Net faithfully captures both the deterministic logic from requirements specifications and the adaptive capabilities from data-driven learning components, providing a comprehensive model for subsequent formal analysis and verification.

3.2. Transformation from Adaptive Petri Net to Hybrid Petri Net

Now we have an Adaptive Petri Net to model an intelligent software system, but it cannot be directly analyzed by model checkers since the structure of an ANN is a computing model, not a state model. Therefore, we need to transform this Adaptive Petri Net model into an equivalent model that can be analyzed by a model checker. In this paper, we transform an Adaptive Petri Net into a Hybrid Petri Net model. This process is divided into two steps.

The Adaptive Petri Net provides a unified model for intelligent software systems, integrating both traditional components and neural network-based A-transitions. However, the subsymbolic nature of neural networks prevents direct application of formal verification techniques. To enable model checking, the Adaptive Petri Net must be transformed into a Hybrid Petri Net, a formalism amenable to analysis by tools such as KeYmaera. This transformation is accomplished through a two-stage process: extracting interpretable fuzzy rules from the embedded neural networks, and converting these rules into a Fuzzy Petri Net structure compatible with the HPN.

3.2.1. Extraction of Fuzzy Rules from the Neural Network

To bridge the gap between neural computation and symbolic verification, we employ the method by Enbutsu et al. [

18] to extract fuzzy rules from the

A-transitions. This approach quantifies the influence between neurons using a

Causal Index (CI), defined as the normalized sum of products of synaptic weights along all paths between two neurons. Formally, the CI from an input neuron

to an output neuron

in a multi-layer perceptron is computed as:

Subsequently, the Relative Index (RI) is derived to compare the influence of neurons within the same layer. The rule extraction procedure is as follows:

Identify the output neuron with the highest relative activation degree.

Determine the output proposition with the strongest causal link to ; this forms the rule’s conclusion.

Locate the input neuron with the highest RI value influencing ; this constitutes the rule’s condition.

This process yields fuzzy rules of the form “IF THEN ”, approximating the neural network’s decision logic.

3.2.2. Transformation of Fuzzy Rules into a Fuzzy Petri Net

The extracted fuzzy rules are integrated into the Hybrid Petri Net by using a Fuzzy Petri Net representation based on Chen et al. [

19,

20]. Each fuzzy rule of the form:

where

and

are fuzzy propositions and

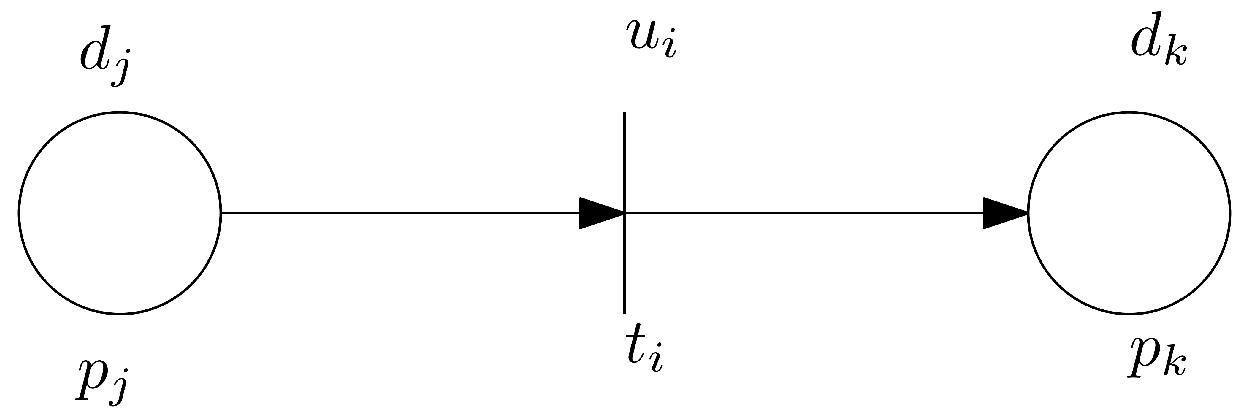

is the certainty factor, is mapped to an FPN structure as follows:

A place represents the antecedent proposition , holding a token with a truth value in .

A place represents the consequent proposition , similarly associated with a truth value.

A transition connects to , annotated with the certainty factor .

The firing semantics of

compute the truth value of

as the product of the truth value of

and

. This structure, illustrated in

Figure 2, enables the Hybrid Petri Net to model both precise and approximate reasoning within a unified verification framework.

3.3. Identification of Defective Components via Model Checking

3.3.1. Model Checking of Hybrid Petri Nets

To verify the properties of the Hybrid Petri Net, we first transform it into a corresponding hybrid automaton (HA) following the methodology established by David and Alla [

21]. We then employ the KeYmaera theorem prover [

22] to formally analyze the resulting HA. The underlying methodology proceeds as follows.

An HPN can be characterized by an evolution vector, which comprises the set of enabled discrete transitions and the markings of the continuous places. Each reachable state corresponds to a specific evolution vector, and the hybrid automaton can be systematically derived from the evolution graph of the HPN. When using the KeYmaera prover, a system property is specified as an implication of the form , where the precondition characterizes the initial state of the system, and the postcondition declares a condition that must hold for all reachable states. Both conditions are expressed as constraints over a set of declared variables. Consequently, such a property asserts that if the precondition holds initially, then after any execution of the system, all reachable states must satisfy the postcondition.

3.3.2. Localization of Defective Components from Violated Properties

The identification of defective components within a model is guided by the analysis of violated properties. As established in the previous subsection, each property is formulated as a constraint over a set of variables; consequently, property violation indicates that the actual values of these variables diverge from the constraints prescribed by the property. Such deviations in variable values result from erroneous modifications or behaviors in specific components of the model.

To localize the model components responsible for property violations, we systematically trace how the values of property-related variables are altered during system execution. By correlating the unsatisfied properties reported by KeYmaera with the corresponding variable dependencies in the system model, we effectively isolate the defective parts of the model that lead to the observed violations.

3.4. Tracing Deficient Data Through Inverse Mapping

To effectively trace deficient data, we propose a two-stage inverse mapping approach that reconstructs potential sample data from fuzzy rules. The method proceeds as follows:

(1) Mapping Fuzzy Sets to Intervals

Building upon the rule generation process in [

23], which partitions fuzzy variables into sub-intervals and assigns membership via the maximum membership principle, we establish an inverse mapping from fuzzy rules back to data intervals. Given a fuzzy rule of the form:

we infer that variable

must lie in the interval

corresponding to fuzzy set

M, as dictated by the maximum membership principle. Similarly, intervals for

and

y are derived from fuzzy sets

L and

, respectively.

(2) Locating Data via Dictionary-Guided Search

While the first step identifies candidate intervals, the number of possible data points within each interval remains infinite. To efficiently locate relevant data from the original sample set, we introduce a dictionary-based prioritization strategy. For rule R, suppose the sample data contain the following:

500 records where belongs to M.

100 records where belongs to L.

430 records where y belongs to .

We construct a search dictionary as follows:

Records are then searched in ascending order of frequency:

,

y, and

. This “dictionary-increase” method ensures that dimensions with fewer matching records are prioritized, reducing the search space efficiently and systematically.

4. Case Study: Deficient Data Tracing in Manufacturing Systems

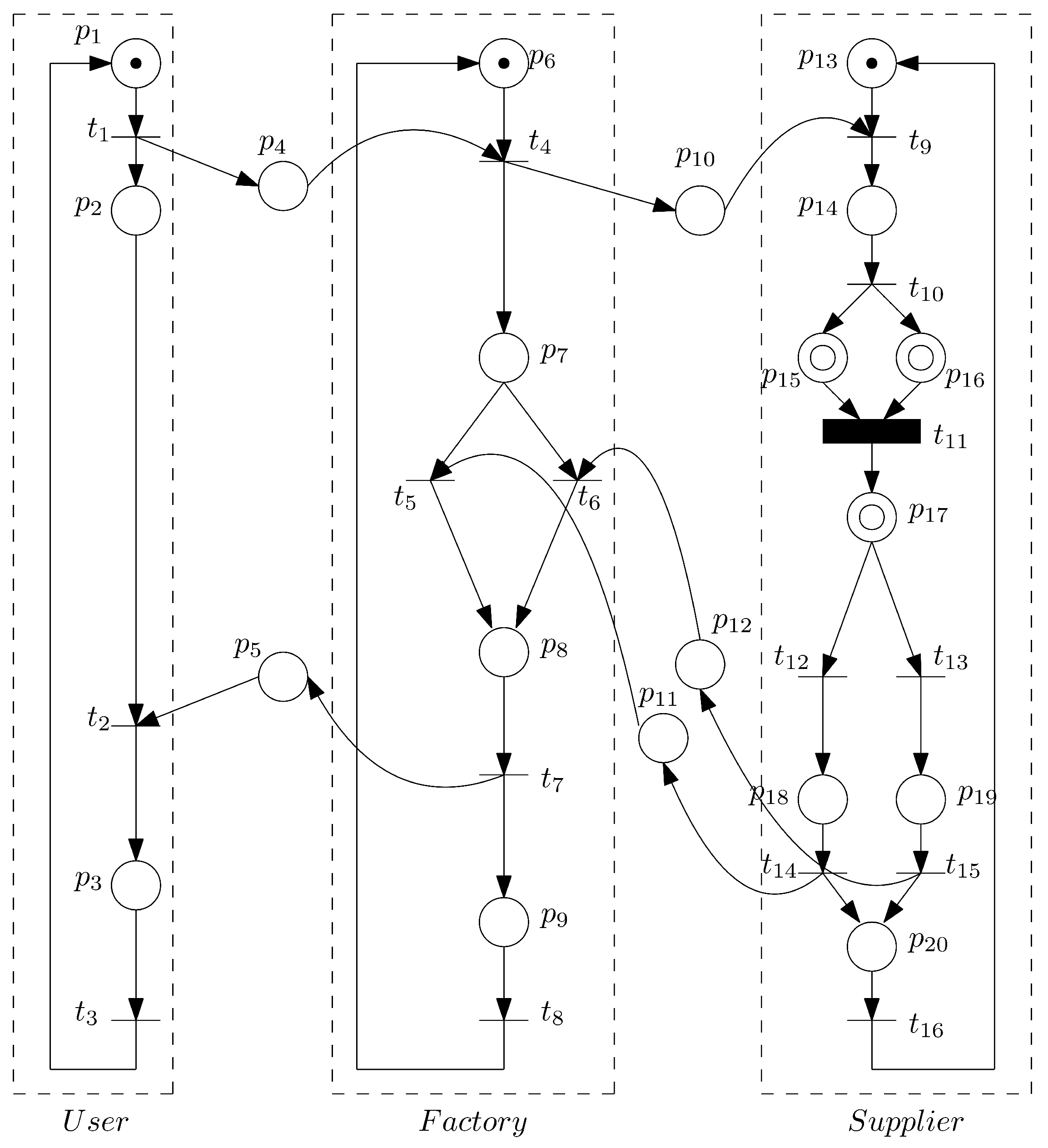

This case study demonstrates how deficient sample data can adversely affect trained neural network models and consequently compromise system properties through a simplified manufacturing system example [

24]. The system coordinates customers, factories, and suppliers, with two suppliers (

and

) selected based on material quality (MQ) and material cost (MC).

provides high-quality materials at premium costs, while

offers lower quality at reduced costs, with an intelligent subsystem enabling dynamic supplier selection in response to market fluctuations.

The neural network was initially trained using the dataset in

Table 1, employing a three-layer artificial neural network for supplier selection. The network architecture consists of 4 input neurons (corresponding to four environmental factors), 5 hidden neurons, and 1 output neuron, with the hidden layer using a hyperbolic tangent sigmoid activation function (coefficient = 4). Training utilized the backpropagation algorithm with Nguyen–Widrow weight initialization, with key hyperparameters set as learning rate

, accuracy threshold

, and maximum iteration count

, terminating when either maximum iterations were reached or error

E fell below

.

The complete Adaptive Petri Net model is shown in

Figure 3, while fuzzy rules extracted from the neural network appear in

Table 2, where

represents material quality,

material cost, and

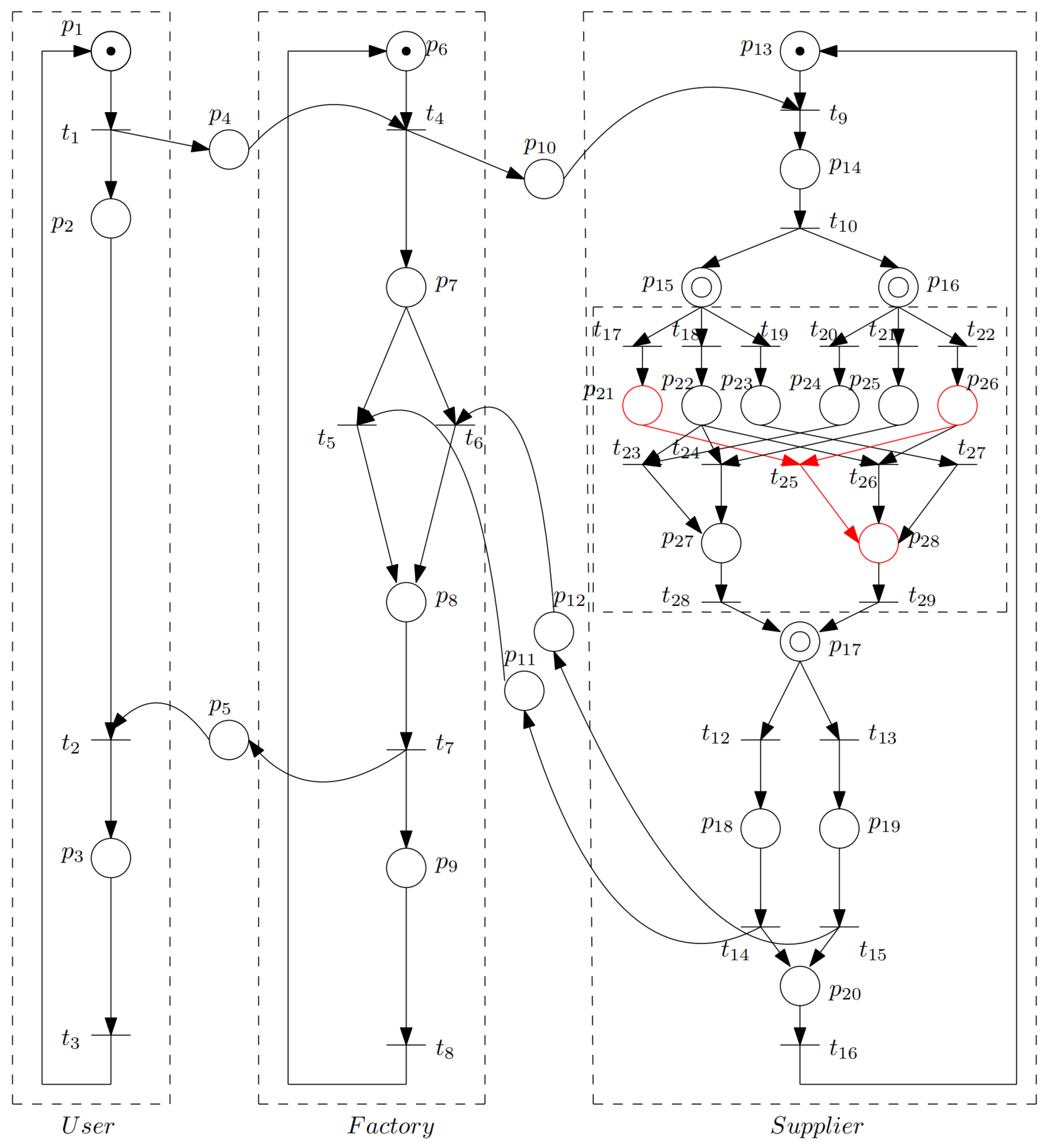

y the selected supplier. The corresponding HPN model (

Figure 4) transformed from an APN highlights the sub-net implementing the

A-transition

from

Figure 3. Then we apply the model checking technique to check a property:

(P): “If the customer requests for high quality material and is willing to sacrifice to material cost, then should be selected”.

We formulate this property as , where the variable represents the precondition that requires high-quality material, the variable specifies the hybrid system dynamics given as a hybrid program, and the variable represents the selection of .

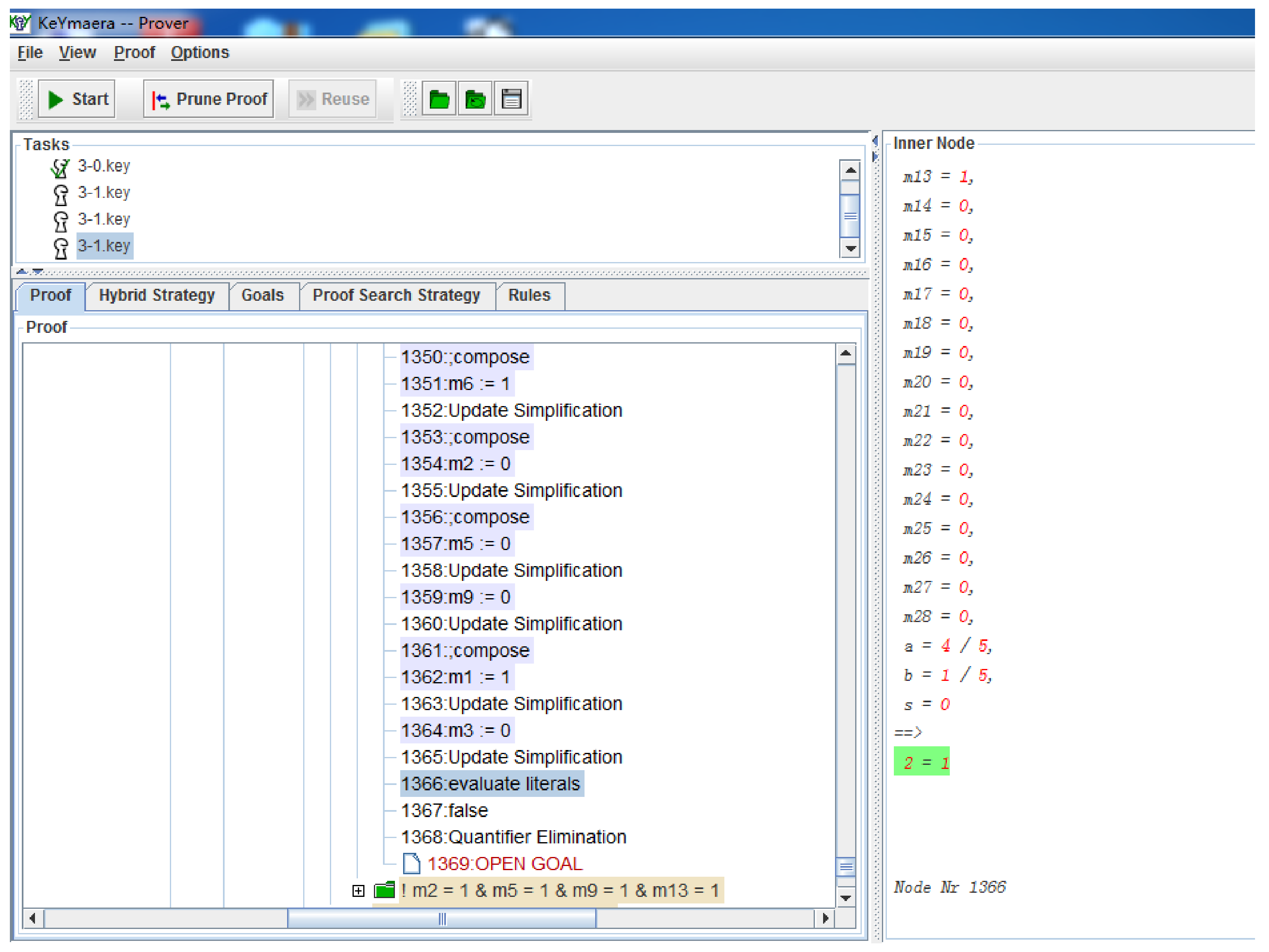

Then, we run KeYmaera to verify this property, and it gives the result “

2 = 1” in the

Inner Node part of this tool, which is shown in

Figure 5. This means that supplier

is selected which indicates that the model violates the property.

Proof analysis traced the error to place

(highlighted red in

Figure 4) in the neural network sub-net responsible for intelligent supplier selection, where miscalculation propagated through the network to affect system-level behavior. Using our two-stage inverse mapping approach, we identified deficient data corresponding to the problematic fuzzy rule “If

is high and

is low, then

y is

,” with located data positions shown in

Table 3 (red highlighting potential deficiencies).

After modifying 200 data pairs in the original dataset (

Table 4, red indicates changes) and updating fuzzy rules (

Table 5). The model now satisfies property

(P), confirming that corrected sample data enables proper system behavior. While systematic deficient data improvement methods fall outside this paper’s scope, this case demonstrates the critical relationship between data quality and model correctness.

5. Discussion

This paper presents a model verification-based framework for tracing deficient data that leads to property violations in intelligent software systems. Our primary contribution lies in pioneering the application of formal modeling and verification traceability to address data quality diagnosis challenges. By systematically integrating established techniques—including Adaptive Petri Nets, Hybrid Petri Nets, and fuzzy rule extraction—the framework establishes a traceable link from system-level property violations to specific training data subsets, providing a structured approach for verifying “black-box” intelligent components.

A key consideration in our methodology is the approximation error inherent in fuzzy rule extraction. While this process effectively captures the dominant decision patterns of the original neural network, it inevitably introduces precision loss when converting continuous neural activations into discrete fuzzy rules. This approximation mainly impacts the fine-grained boundaries between decision regions, consequently affecting the accuracy of deficiency data localization. Notably, when handling high-noise input data or facing the curse of dimensionality, the rule extraction process may yield misleading outcomes—such as generating contradictory rules—that could compromise result reliability. Through our case study, we confirmed that while this approximation error does not fundamentally undermine deficient data detection, it does represent a crucial trade-off between interpretability and precision that requires careful consideration in implementation. For more precise assessment of this trade-off, future work should incorporate specialized evaluation metrics—such as rule consistency indices and boundary fidelity measures—along with enhanced validation methods, including adversarial testing and uncertainty quantification techniques, to better evaluate and mitigate these approximation effects.

Several limitations of this work warrant acknowledgment and present promising research directions. First, our strategic choice to integrate existing technical frameworks rather than develop novel algorithms enabled us to validate the core concept of system-to-data traceability. This approach demonstrates that current formal methods can effectively construct such traceability pathways, establishing a foundation for future research before introducing more complex theoretical constructs.

In terms of experimental evaluation, the streamlined case study successfully illustrated the complete workflow from property definition through data localization—a demonstration that would be challenging in larger, complex systems. However, we recognize that establishing industrial-grade effectiveness requires future work incorporating more extensive case studies, rigorous quantitative metrics, and baseline comparisons. Standardized disclosure of neural network architectures and training parameters also remains crucial for reproducible research.

Finally, challenges regarding framework scalability and dependence on fuzzy rule extraction accuracy represent significant opportunities for community investigation. The methodology’s effectiveness is inherently tied to the quality of rule extraction, particularly in systems requiring high-precision decision boundaries. Future work should focus on developing more refined extraction techniques that balance interpretability with minimal approximation error.

In summary, this study demonstrates the feasibility of using formal methods for data deficiency diagnosis while highlighting important considerations for practical deployment. Subsequent research can build upon this foundation through more complex case studies, automated data correction algorithms, and optimized performance to advance this promising direction.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a model-based framework for detecting deficient data in intelligent software systems through formal verification, which integrates neural networks with system models using Adaptive Petri Nets and employs model checking to trace system-level property violations back to specific deficiency data. The key advantage of our method over traditional approaches lies in its system-level perspective and explainable nature—instead of treating neural networks as black boxes and relying on experience-driven parameter tuning, our framework provides a principled way to identify data deficiencies through their actual impact on system properties, as demonstrated in the manufacturing system case study where property violations were successfully traced to problematic data instances and model correctness was restored after data revision. This approach offers crucial insights for developing reliable intelligent systems, particularly in safety-critical domains where understanding the root cause of failures is essential.

In the future, we plan to undertake the following work:

- (1)

Extending the framework to larger, more complex systems and conducting quantitative evaluations with established metrics;

- (2)

Investigating the accuracy of fuzzy rule extraction in representing ANN behavior and developing automated data correction mechanisms; and

- (3)

Adapting the framework to verify systems with diverse AI components beyond standard neural networks.