1. Introduction

Modern processors rely heavily on speculative execution and advanced branch prediction techniques to maintain high performance in the presence of control-flow changes. As instruction pipelines deepen and out-of-order execution becomes more aggressive, accurately predicting the targets of indirect and conditional branches is critical to avoiding pipeline stalls and preserving throughput. One of the key hardware structures that enables this capability is the Branch Target Buffer (BTB), a cache-like structure that records the target addresses of recently executed branches. Upon encountering a control-transfer instruction during instruction fetch, the processor consults the BTB to predict the branch target without waiting for full decoding and execution, thereby accelerating instruction flow.

Over the years, extensive research has been conducted on reverse engineering Branch Target Buffer (BTB) structures [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Most prior studies have focused on ×86 processors, employing carefully crafted microbenchmarks to characterize BTB parameters such as the total number of entries, set-indexing bits, and associativity. These investigations have established a methodological foundation for empirically analyzing branch predictor microarchitectures, contributing valuable insights to both performance optimization and security analysis in conventional desktop and server systems.

While the design and behavior of BTBs have been widely investigated and documented in ×86-based processors, little is publicly known about their implementation in ARM-based SoCs (System-on-Chip) [

5]. Since Apple’s transition from Intel ×86 to its in-house ARM architecture, starting with the M1 chip, Apple Silicon has become a prominent platform powering millions of devices. Despite its widespread use and high performance, its microarchitectural components, especially the BTB, remain largely undocumented and opaque to the research and developer community. Understanding the BTB’s structure and behavior is not only important for performance optimization and microarchitectural modeling but also for evaluating security implications such as branch target injection attacks [

4,

6,

7,

8] and speculative execution vulnerabilities [

9]. However, due to Apple’s proprietary design and lack of public documentation, rigorous empirical investigation is required to characterize its internals.

Although a prior work [

5] successfully reverse engineered the BTB structure on an ARM Cortex-A76 processor using controlled microbenchmarks, directly applying this approach to ARM-based Apple Silicon introduces several unique challenges. First, Apple Silicon on macOS lacks direct access to low-level PMU (Performance Monitoring Unit) events that are typically used to monitor branch prediction behavior. Second, Apple’s unified CPU-cluster design, combining performance and efficiency cores, complicates the process of isolating BTB behavior across heterogeneous execution contexts. And most importantly, its codes and many architectural features are closed-source and undocumented, limiting visibility into internal predictor mechanisms. Addressing these challenges is essential for accurately uncovering the BTB organization within Apple SoCs.

In this paper, to successfully reverse engineer the BTB structure of Apple Silicon by overcoming these challenges, we extend existing methodologies [

2,

5] by leveraging the m1n1 proxy framework

m1n1 with custom ARM64 microbenchmarks tailored for the Apple M2 processor. The proxy mode of

m1n1 enables interactive, low-latency communication between a host computer and the target Apple Silicon device over USB. This design enables executing handcrafted ARM64 microbenchmarks directly on the CPU with minimal operating-system interference in a near-bare-metal environment, effectively isolating the test loop from kernel noise and timing jitter. Moreover, its Python3-based scripting interface allows rapid prototyping and automation of test scenarios, greatly simplifying the design and execution of targeted microbenchmarks on otherwise closed hardware. Using the m1n1 proxy, we execute each microbenchmark on a specific core to ensure consistent measurement conditions and eliminate interference from the heterogeneous cluster design. In addition, through m1n1’s low-level MMIO interface, we directly access branch misprediction counters and other microarchitectural registers to collect precise performance data.

Building on this experimental setup, we conduct the first detailed reverse engineering study of the BTB on Apple Silicon, focusing on the M2 processor. Through carefully designed microbenchmarks, we characterize key BTB parameters, estimating that the M2 BTB comprises approximately 2 K entries, employs nine set index bits, and features four-way associativity. These findings provide practical guidance for low-level code optimization and timing analysis while also supporting microarchitectural and security research on branch prediction mechanisms. Moreover, our results contribute to education and future studies by offering deeper insights into the operation of Apple Silicon’s branch predictor structures.

2. Background and Related Work

This section provides the necessary background on branch prediction mechanisms and surveys prior work on reverse engineering branch predictors, with a particular focus on studies relevant to Apple Silicon.

2.1. Branch Target Prediction

Modern processors rely heavily on branch prediction to sustain instruction throughput in the presence of frequent control-flow changes. Branch prediction mechanisms speculatively resolve the outcomes and targets of branches before their actual execution, thereby reducing pipeline stalls and preserving instruction-level parallelism. A core component of this infrastructure is the Branch Target Buffer (BTB), which caches the targets of previously executed control-flow instructions. When the processor encounters a branch, it consults the BTB to quickly redirect instruction fetch without waiting for branch resolution.

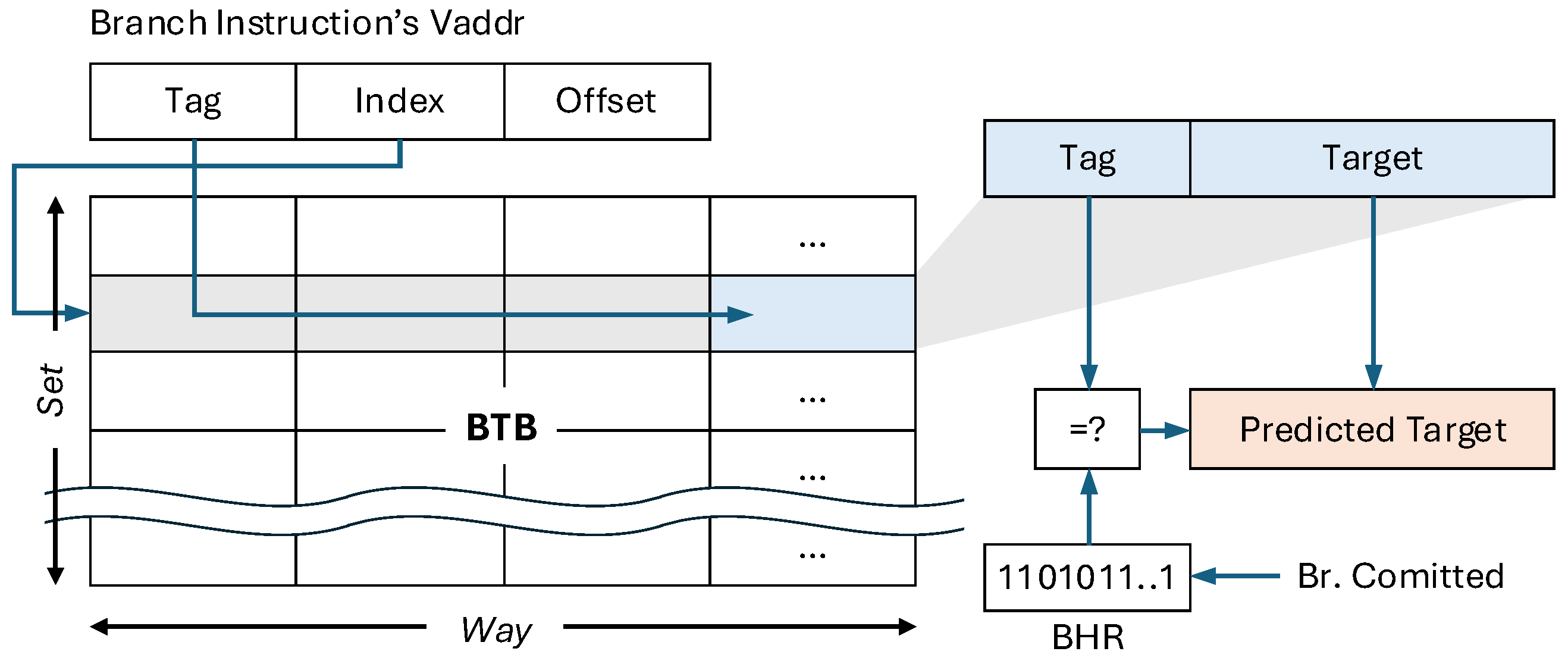

To retrieve a target address from the BTB, a branch instruction’s virtual address is decomposed into tag, index, and offset fields, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The index selects a specific set within the BTB, while the tag is compared across multiple ways to detect a match. On a hit, the BTB supplies the predicted target address, enabling the processor to continue fetching instructions speculatively without waiting for the branch to be resolved.

For direct branches, the BTB provides the target address directly. In contrast, for indirect branches, the BTB often cooperates with the Branch History Register (BHR), which captures dynamic execution history to refine prediction accuracy. This interaction between the BTB and BHR improves performance but also adds complexity to the predictor’s design. The BTB’s set-associative structure, while essential for balancing accuracy with hardware efficiency, inevitably introduces challenges such as aliasing and limited capacity that can degrade prediction quality.

Although these mechanisms have been extensively studied in ×86 processors, the internal design of BTBs in ARM-based systems—and particularly in Apple Silicon—remains largely undocumented. Consequently, empirical studies are necessary to reveal how Apple’s proprietary predictors operate in practice. Understanding this behavior is not only critical for performance optimization and microarchitectural modeling but also for evaluating potential vulnerabilities, including branch target injection attacks and speculative execution–based exploits.

2.2. Reverse Engineering Branch Predictions

Early work on demystifying branch predictors in commodity CPUs established much of the methodology used today. Milenkovic et al. [

2] described foundational techniques for analyzing Intel branch predictors, outlining practical experiments that reveal indexing, tagging, and interference behavior. Building on this, Uzelac et al. [

10] systematized microbenchmark experiment flows for reverse engineering predictor structures, which remain the canonical template for probing BTB capacity, indexing bits, and associativity. Beyond microarchitectural characterization, recent security-driven studies have highlighted how predictor internals intersect with transient execution: for example, Li et al. [

4] demonstrates high-precision branch target injection by leveraging detailed knowledge of indirect branch prediction components, while work on constructing transient-execution trojans further underscores the need to understand predictor organization and isolation guarantees [

3].

Efforts on Apple Silicon. Since Apple Silicon’s predictor design is undocumented, recent research has adapted ×86-style methodologies to ARM/Apple platforms. Chen et al. [

11] dissect conditional branch predictors on Apple’s Firestorm cores (and Qualcomm Oryon), offering insights relevant to software optimization and architectural analysis. Wan [

5] provides a targeted study on BTB reverse engineering for ARM, using controlled microbenchmarks to infer organization parameters, an approach directly applicable to Apple SoCs. Tuby et al. [

12] reverse engineer the Apple M1 conditional branch predictor and expose conditions enabling out-of-place Spectre mistraining, strengthening the case for rigorous BTB/BPU characterization on Apple chips. Zhou [

13] complements these efforts with practical experiments and tooling for the Apple M1 Branch Prediction Unit (BPU), improving reproducibility for community studies. Collectively, these works rooted in [

2] form the methodological basis for characterizing BTB capacity, index mapping, and associativity on Apple SoCs.

3. Reverse Engineering the Apple M2 Branch Target Buffer

In this section, we present our methodology for reverse engineering the Apple M2 BTB, detailing the experimental environment, microbenchmark design, and measurement procedures for inferring its capacity, set indexing behavior, and associativity.

3.1. Experimental Environment

3.1.1. Hardware and Software Platform

To reverse engineer the BTB on Apple Silicon, we conducted a series of carefully designed microbenchmark experiments in a controlled and low-noise environment. All experiments were performed on a Mac mini (2023 model) featuring the Apple M2 System-on-Chip. This processor includes four high-performance Avalanche cores and four energy-efficient Blizzard cores, along with 8 GB of unified memory and a 256 GB SSD. In this work, we focused our investigation on the high-performance Avalanche cores because they are the primary execution resources under typical workloads.

The experimental setup was based on Asahi Linux [

14], a community-driven Linux port for Apple Silicon, in combination with

m1n1 [

15], a low-level bootloader and hypervisor framework developed to expose internal features of Apple’s proprietary hardware. We specifically employed

m1n1’s proxy mode, which enables interactive, low-latency communication between the host system and the target device over USB. This mode allows researchers to execute custom machine-level payloads directly on the CPU with minimal operating system interference, effectively transforming the Apple Silicon platform into a research-friendly testbed.

Methodological scope and licensing considerations. All experiments in this study were conducted using software-only microbenchmarks executed through the m1n1 proxy interface. We did not use any invasive techniques (e.g., physical probing, hardware modification, or privileged debug features) and relied solely on publicly accessible system functionality. This methodology respects Apple’s applicable licensing terms and is intended strictly for academic microarchitectural analysis.

3.1.2. Noise Minimization Using m1n1

Using the m1n1 proxy helps minimize measurement noise during microbenchmarking by providing a highly controlled and deterministic execution environment. First, because m1n1 runs code directly on bare metal, it eliminates interference from the operating system, such as scheduling, interrupts, and background daemons. This isolation ensures that experimental results reflect the behavior of the target microarchitectural components rather than external software noise. Second, m1n1 supports core pinning, allowing benchmarks to execute consistently on a dedicated core without context switching or migration overhead. This prevents performance fluctuations caused by core reassignment or shared resource contention. Finally, it allows access to Performance Monitoring Counters (PMCs) to collect event data. This approach avoids timing jitter and further reduces measurement variability, providing more stable and accurate results.

Based on these features, our experimental environment provides the fine-grained visibility and control necessary to reverse engineer BTB properties such as size, set indexing, and associativity on Apple’s proprietary processors. The combination of bare-metal benchmarking and m1n1 proxy execution is instrumental in producing consistent and reproducible measurements on a platform that is otherwise opaque to traditional performance analysis tools.

3.1.3. Measuring BTB Misprediction

Our reverse engineering of the BTB relies on branch-misprediction measurements. In particular, we infer whether predictions are being served by the BTB by observing mispredictions under controlled execution patterns. To this end, we run custom microbenchmarks through the m1n1 proxy interface. These microbenchmarks are hand-written in ARM64 assembly to provide fine-grained control over instruction sequencing and branch behavior. While executing sequences of indirect, unconditional branches with varying branch offsets and branch counts, we collect mispredictions of the indirect-branch executions.

Measurements were collected using PMCs during benchmark execution. To assess prediction accuracy, we can employ three PMC events that capture different classes of branch mispredictions: the all-branch misprediction counter (

0xCB), the conditional-branch misprediction counter (

0xC5), and the indirect-branch misprediction counter (

0xC6) [

16]. Because our microbenchmarks exclusively use indirect branches, we primarily rely on the indirect-branch misprediction counter to evaluate prediction accuracy and infer BTB behavior. Note that we did not find any PMC event that reliably measures direct branch mispredictions, so we designed our microbenchmarks using indirect branches, as described in the following section.

3.2. Microbenchmark Design

The branch predictor may employ a single, unified BTB for both direct and indirect branches, rather than maintaining separate structures, to maximize utilization of branch prediction unit (BPU) storage resources [

3,

17]. In this work, we initially hypothesize that the Apple M2 may employ a unified BTB design, similar to ARM implementations [

5]; however, our findings later suggest the possibility of a multi-level (L1/L2) BTB hierarchy. A potential hierarchical BTB design is further discussed in

Section 5.

Following prior work [

5], our microbenchmarks therefore employ a series of indirect unconditional branches implemented using two ARM instructions, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The

ADR instruction loads the address of the next branch target, and the

BR instruction jumps to that address. These instructions are repeated across multiple labels to examine the BTB and evaluate its capacity, set indexing, and associativity. Using this primitive, we design three microbenchmarks to analyze the BTB’s organization, as shown in

Figure 3. Each benchmark relies on the same underlying branch chain but varies the parameters

B (number of branches) and

D (stride distance) to test different aspects of the BTB, as summarized in

Table 1. The intuition behind each benchmark is as follows.

Capacity test: increase the number of distinct indirect branches B at a fixed inter-branch distance D to locate the inflection in misprediction rate (MPR), which estimates the total number of BTB entries while minimizing set conflicts.

Index bits test: sweep D (thus shifting which virtual address bits participate in indexing) at fixed B within capacity, to reveal the number and position of index bits.

Associativity test: fix the inferred index (by keeping D constant) and vary the tag bits via address offsets to determine the eviction threshold and infer the set associativity W.

This tripartite structure ensures that capacity, set index bits, and associativity can be inferred independently with minimal interference. In the following section, we describe each benchmark in detail.

3.2.1. Capacity Test

Following the approach of prior work [

10], we begin our analysis of the BTB organization with a test commonly known as the

BTB capacity test. This test stresses the BTB by attempting to determine the maximum number of branches

B it can accommodate. These branches are arranged in a loop at evenly spaced memory intervals defined by a distance

D. By varying the values of

B and

D, it is possible—under certain conditions—to estimate the BTB’s total capacity

and infer details about its internal organization.

To pinpoint the capacity threshold, we gradually increase the number of branches

B while keeping

D fixed, as shown in

Figure 3a. The point at which misprediction rates sharply rise corresponds to the BTB’s approximate capacity limit. This method assumes that branch addresses are evenly mapped across sets, minimizing the impact of aliasing and conflicts. By repeating the experiment, we can confirm consistency in the observed capacity and rule out set-mapping anomalies. These results collectively provide a practical estimate of the total number of entries

in the BTB.

3.2.2. Index Bits Test

To determine the number of set index bits used in the BTB, we conduct experiments that vary the memory distance

D between adjacent branches while keeping the number of branches

B fixed and within the known BTB capacity, as illustrated in

Figure 3b. Since the BTB typically uses a subset of address bits to index into sets, altering

D effectively changes which bits contribute to the indexing process.

We begin by placing branches at varying distances D, then observe the resulting misprediction rates. When branches map to distinct sets, the BTB can store their targets without conflict, resulting in low misprediction rates. However, if multiple branches map to the same set due to overlapping index bits, conflicts arise, and misprediction rates increase.

Finally, by identifying the ranges of distance D over which mispredictions rise sharply, we can estimate the bit positions used for set indexing. Repeating the experiment while sweeping D refines this estimate and reveals how many bits are used for indexing, thereby indicating the number of BTB sets.

3.2.3. Associativity Test

Once the number of sets and the corresponding index bits have been identified, we next estimate the associativity of the BTB set. This involves determining how many branches can be mapped to the same set before evictions or mispredictions occur.

In this test, we construct a sequence of indirect branches that all map to the same BTB set by fixing

D so that the index bits remain constant (i.e., choosing

D to align with the inferred set index bits) while varying only the tag bits. We then sweep

B, gradually increasing the number of distinct branches from 2 to 16, and record the number of mispredictions (see

Figure 3c).

Intuitively, when (where W is the set associativity), the BTB can hold all targets and mispredictions remain near zero. As B exceeds W, evictions begin and the misprediction count rises roughly with (B − W) under an LRU-like replacement policy. Thus, observing a stable pattern of two mispredictions when is consistent with an associativity of approximately . In practice, we repeat each configuration multiple times and look for the smallest B at which mispredictions persistently appear and scale with B; this threshold provides an empirical estimate of W.

4. Results

In this section, we present the outcomes of our microbenchmark experiments conducted on the Apple M2 processor to reverse engineer key parameters of its BTB. The results are organized into three parts, corresponding to the tests described earlier: capacity, set index bit, and associativity. Each set of experiments was designed to stress a different aspect of the BTB’s behavior, allowing us to infer its effective size, the number of index bits involved in set selection, and the degree of associativity.

For all three microbenchmarks (capacity, set index bits, and associativity tests), we executed each configuration 100 times and report the mean results. Error bars in the corresponding figures indicate the standard deviation across these repeated trials. We focus on observable thresholds and transition points in branch misprediction rates, which provide empirical evidence about the BTB’s internal organization. Although our results reveal consistent patterns suggestive of a particular organization, we do not draw definitive conclusions about the Apple M2’s BTB; Apple’s design may merely appear to align with our microbenchmark observations while, in reality, deviating from our description.

4.1. Capacity

To estimate the BTB size of the Apple M2 processor, we conducted the BTB capacity test by executing a varying number of distinct indirect branches while fixing the inter-branch distance

D = 3. The number of branches

B was increased from 1 K to 8 K, and we measured the corresponding branch misprediction rate (MPR). Each (

B,

D) configuration was repeated 100 times, and

Figure 4 plots the mean MPR with standard deviation error bars. As shown in

Figure 4, the misprediction rate remains near zero when the number of branches is below approximately 2 K. This indicates that the BTB can successfully store all the branch targets within this range, with minimal evictions or conflicts. However, as the number of branches exceeds 2 K, the MPR increases sharply, approaching nearly 80% by the time

B = 8 K. This result indicates that the BTB reaches its storage capacity around 2 K branches.

The sharp transition in MPR implies a relatively direct correlation between the number of stored branches and the BTB’s effective entry limit. Given this observation, we estimate that the Apple M2’s BTB contains approximately 2 K entries.

4.2. Set Index Bit

To investigate the number of set index bits used by the BTB, we performed a BTB set index test by varying the memory distance

D between adjacent branches while keeping the number of distinct branches fixed at

B = 2 K. The memory distance

D was swept from 3 to 19, which effectively shifts the positions of the branch address bits used for indexing. For every distance

D, we performed 100 trials and report the mean MPR with standard deviation error bars in

Figure 5.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the MPR remains consistently low for distances

, indicating that branches are likely distributed across different sets with minimal contention. However, starting from

D = 13, the MPR begins to increase significantly, and by

D = 14, it nears 100%. This sharp rise suggests that the index bits used by selecting the BTB set fall within the lower 4 to 12 bits of the branch address.

These results imply that the BTB uses approximately 9 bits for set indexing, corresponding to = 512 sets. Distances below this threshold allow branches to tend to map to separate sets, while larger distances cause aliasing into the same set, leading to conflicts and increased mispredictions. This behavior confirms the BTB’s set-associative nature and provides a precise estimate of the number of index bits involved in set selection.

4.3. Associativity

Figure 6 presents the number of mispredictions of indirect branches observed as the number of executed branches

B varies. In this experiment, the

D value was fixed at 8, meaning that the lower eight bits of the virtual branch addresses were zeroed to force the targets into the same index set of the BTB. To eliminate interference from global history, each run was preceded by a fixed sequence of conditional branches, ensuring that the BHB was identical at the start of every trial. The first run initializes the BTB by inserting the target branches, and the second run measures MPR to check for mispredictions against these stored targets. Each

B setting was evaluated over 100 repeated runs, and

Figure 6 summarizes the resulting distribution across trials.

The results show a clear capacity point consistent with four-way associativity. As the number of branches B increases while holding the set index fixed, the misprediction count rises roughly as B = 4: for example, with B = 6 we frequently observe 2 mispredictions, with B = 8 about 4, with B = 10 about 6, with B = 12 about 8, and with B = 14 about 10. This linear trend beyond the threshold implies that the BTB can reliably hold four targets per set; once B > 4, additional branches evict existing entries and drive mispredictions, indicating an effective associativity of approximately 4 ways under our test conditions.

5. Discussion

Our reverse engineering study of the Apple M2 BTB provides new insights into its organization and behavior, yet several broader implications emerge when considering the role of multi-level BTBs and the possibility of BTB prefetching mechanisms. This section discusses these implications and the evidence from our measurements, suggesting that Apple’s design may combine ARM-like efficiency with hierarchical sophistication similar to ×86 processors.

L1/L2-BTB Design. Modern high-performance processors often employ a hierarchical BTB design: a small, low-latency Level-1 BTB (L1-BTB) holds the most frequently accessed branch targets, while a larger, higher-capacity Level-2 BTB (L2-BTB) captures less frequent targets, balancing access latency and prediction accuracy [

18,

19,

20]. Although our experiments indicate an effective M2 BTB capacity of approximately 2 K entries with roughly 4-way associativity, the associativity experiment in

Figure 6 suggests more than one resident structure is involved. Specifically, when we execute the same set of branches repeatedly, mispredictions often persist in the second run but disappear by the third run even when

B >

W = 4. This “three-run convergence” was observed across multiple (

B,

D) configurations, indicating a systematic warm-up behavior rather than noise. One plausible interpretation is that the first run allocates targets into a fast L1 BTB while also triggering fills into a backing BTB (e.g., L2 BTB). The second run then encounters fewer misses as the backing structure becomes established, and by the third run, both levels track the working set, eliminating mispredictions. This behavior supports the presence of a hierarchical BTB design in which the L1 BTB provides low-latency predictions, and the L2 BTB functions as a larger-capacity backing store that requires multiple accesses to warm up. Note that an online source [

21] mentions the Apple M1’s L2 BTB size; however, this has not been definitively confirmed.

BTB Prefetching. Another aspect worth discussing is the potential presence of a BTB prefetcher. Prefetching, traditionally associated with data and instruction caches, has also been explored in the context of branch prediction [

22,

23]. A BTB prefetcher could proactively populate the BTB with likely future targets based on program counter strides or loop structures, thereby reducing cold-start latency and mitigating thrashing under high branch density.

Figure 6 contains an additional anomaly that aligns with such a mechanism. Under the 4-way model, as suggested by the approximately linear trend MPR ≈

for moderate

B, we would expect about 12 mispredictions at

B = 16; instead, the outcomes cluster around ∼10. This shortfall implies that some targets are being preserved or inserted beyond what a single 4-way set would allow, consistent with assistance from a backing BTB level, a prefetcher, or both. Importantly, this deviation appears only after a certain branch-count threshold is crossed, matching the intuition that auxiliary prediction support (i.e., prefetching) activates primarily under high set pressure.

While our experiments indicate a single observable BTB capacity, establishing the existence of hierarchical BTBs and prefetching mechanisms requires additional microbenchmarks capable of distinguishing between fast-path predictions and longer-latency lookups. In addition, cross-core studies may clarify whether BTB state is shared or partitioned between performance and efficiency cores. Such analyses would deepen our understanding of Apple’s proprietary predictor design, contributing both to performance optimization and to the mitigation of microarchitectural attacks. Finally, the interaction between L1 and L2 BTBs, together with potential prefetching policies, may introduce subtle new side channels that merit further investigation. Fully reversing the detailed hierarchy geometry (e.g., exact L1/L2 capacities, indexing relations, and fill/eviction policies) and any prefetch trigger rules remains an open direction for future work.

Comparison with Prior Works. Prior reverse engineering studies on ×86 processors [

2,

10], revealed large and complex BTB hierarchies with capacities above 8 K entries and associativity levels of 4–8 ways. These designs, common in Intel and AMD architectures, emphasize high prediction coverage and performance scalability. In contrast, ARM-based designs, including the Cortex-A76 [

5], adopt smaller BTBs of about 4 K entries, 11 set index bits, and 2-way associativity, favoring lower power and simpler organization, as summarized in

Table 2. Prior reverse engineering works [

13,

21] on the Apple M1 also point to a small BTB capacity but report only the BTB size, leaving set/index structure and associativity unspecified. Our findings on the Apple M2, showing approximately 2 K entries, 9 set index bits, and 4-way associativity, exhibit a pattern broadly consistent with an ARM-style BTB organization. However, the observed multi-run convergence behavior suggests possible multi-level BTB or prefetching mechanisms, indicating that Apple’s design may combine ARM-like efficiency with a degree of hierarchical sophistication similar to ×86 processors.

6. Conclusions

This study presented the first empirical reverse engineering study of the BTB on Apple Silicon, focusing on the M2 processor. Through carefully designed microbenchmarks and the use of a controlled experimental environment, we characterized the BTB’s approximate capacity, set indexing, and associativity. Our results suggest that the Apple M2’s BTB contains approximately 2 K entries and is roughly 4-way set-associative, using about 9 branch address bits for set indexing. These findings provide a practical foundation for understanding Apple’s proprietary branch prediction mechanisms, which have remained largely undocumented. Future work will extend our experiments to cross-core interactions, explore possible L1/L2 BTB hierarchies, and evaluate the role of BTB prefetching in both performance and security contexts.