1. Introduction

Cloud services offer scalable, flexible, and on-demand resources that enable enterprises and individuals to deploy applications, store data, and apply artificial intelligence without dedicated infrastructure. As cloud computing evolves, organizations increasingly adopt multi-cloud environments, utilizing services from multiple providers to enhance reliability and performance. The diversity of service providers and offerings introduces significant complexity in service discovery and selection [

1]. To address this, cloud service recommendation has become a vital mechanism for assisting users in identifying appropriate services efficiently and accurately.

Existing cloud service recommendation approaches [

2] can be broadly categorized into the following three paradigms: (i) Collaborative Filtering (CF) methods [

3] analyze user-service interaction patterns to infer preference but suffer from cold-start and data sparsity problems; (ii) Context-aware methods [

4] incorporate external information such as time, location, or device context to enhance personalization, yet often ignore structural characteristics of services [

5]; and (iii) QoS-aware methods [

6] focus on predicting non-functional service attributes such as response time and availability but typically treat services as static entities without modeling their invocation behavior [

7]. While these approaches significantly improve recommendation accuracy from different angles, they generally neglect the behavioral characteristics of services, which can directly affect both the relevance and efficiency of recommendations.

Motivations. Despite the prevalence of service recommendation systems, these methodologies often overlook an important aspect: the behavioral patterns of services within invocation workflows, which significantly impact their practical effectiveness, especially in complex, dynamic environments such as multi-cloud service ecosystems [

8]. In such environments, services are often distributed across different cloud providers, leading to heterogeneous deployment standards, isolated logging mechanisms, and fragmented service invocation paths. These characteristics make it more likely for services to exhibit behaviorally irregular patterns—such as never being invoked together with others, only appearing at the end of workflows, or lacking historical records altogether. We define such anomalies as DBS. Unlike traditional single-cloud or centralized systems, multi-cloud settings amplify the occurrence and impact of DBS, making it imperative to design recommendation mechanisms that are explicitly aware of such behavioral irregularities.

Several key reasons contribute to this oversight: (i)

Ignoring service behavior patterns reduces recommendation efficiency. Some services, such as Isolated Services, rarely interact and may introduce noise, while Ending Services frequently appear as workflow endpoints and should be prioritized. New Member Services, despite lacking historical records, may be crucial in specific contexts. Failing to differentiate these Distinct Behavioral Services (DBS) results in inefficient recommendations and redundant computations. (ii)

Ignoring the dynamic nature of service behavior leads to misclassification and reduced recommendation accuracy. Services transition [

9] between behavioral states due to workload shifts [

10], cloud migration [

11], or user demand changes [

12]. Static models [

13] fail to capture these shifts, making it difficult to distinguish evolving patterns. For example, an Isolated Service may become highly interactive, or an Ending Service may transition to an intermediate role in cross-domain workflows. (iii)

Neglecting DBS cold start and data sparsity issues hinders their effective utilization in recommendation. Many DBSs have low or no historical invocation frequency, making conventional approaches ineffective. However, some DBSs, despite their sparse historical records, should still be prioritized over structurally similar services due to their contextual significance in workflows. In a word, DBSs exhibit fragmented, unstable, or irregular invocation behaviors in multi-cloud service environments, making them difficult to model using conventional scoring techniques. DBSs often suffer from inaccurate or missing recommendation scores due to their structural uniqueness which not only reduces the overall recommendation quality, but also aggravates common issues such as cold-start and data sparsity. To address this, we propose a DBS identification and scoring framework that explicitly models such behavioral structures, offering both improved recommendation fairness and enhanced robustness against sparsity-related challenges. Our approach integrates dynamic monitoring mechanisms to track behavioral shifts over time, ensuring DBS classification remains adaptive to multi-cloud environments.

Challenges. The proposed framework addresses the following challenges (i): Differentiating DBS with similar static invocation patterns. DBS categories can have similar invocation records, making them hard to distinguish. Ending and Isolated Services may both exhibit low frequency, yet serve different roles. New Member Services may resemble inactive services. Effective identification must go beyond static similarity and incorporate topological and temporal features. (ii): Ensuring dynamic adaptability of DBS classification. Service behaviors change over time, requiring adaptive classification. A service may transition from Isolated to Interactive or Ending to Mid-Workflow based on evolving workflows. The challenge is designing an identification mechanism that updates DBS classification in response to real-time behavioral shifts. (iii): Addressing cold start and data sparsity issues. DBS often have limited historical data, making classification difficult. Traditional collaborative filtering and graph-based methods rely on sufficient invocation records, rendering them ineffective for DBS. A robust method should leverage contextual and topological intelligence to infer relevance even in sparse environments.

Contributions. To address these challenges, we make the following contributions:

A Novel DBS Identification Framework. We define Distinct Behavioral Services (DBS) and introduce an invocation topology-based approach to classify services into Isolated, Ending, and New Member Services. Our method captures both topological and temporal features to improve classification accuracy beyond conventional invocation-based methods.

A Dynamic Monitoring and Adaptative Detection of Behavioral Role Shifts based on Sliding Windows. We implement a sliding window mechanism to track behavioral shifts, ensuring DBS classification adapts to evolving interactions. A Markov-based transition model predicts state changes in DBS, preventing misclassification due to short-term fluctuations.

A Markov-Based Scoring Strategy against Cold-Start and Sparse Issues. We design a topology-aware scoring model that leverages the homogeneous and irreducible properties of Markov Chains. This enables complete and stable score propagation for DBS services even when invocation data is sparse or unavailable, effectively addressing cold-start limitations.

Comprehensive Validation Supporting the Proposed Framework. To validate the effectiveness of our framework, we design five dedicated simulations that assess its accuracy, stability, and robustness under cold-start and sparsity scenarios. These evaluations demonstrate the practical viability of our behavior-aware strategies in dynamic service environments.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on collaborative filtering, context-aware, QoS-aware, behavior-aware service recommendation together with cold-start and data sparsity issues.

Section 3 presents the overall architecture of the proposed DBS-aware framework.

Section 4 details the system design, including DBS definitions, invocation topology construction, the DBS-based filtering algorithm, and the sliding time window mechanism.

Section 5 describes the simulation settings, dataset preprocessing, evaluation metrics, and baseline methods.

Section 6 reports and analyzes the experimental results across dynamic environments, temporal stability, data sparsity, and cold-start scenarios.

Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses limitations and future research directions.

4. System Design

4.1. Distinct Behavioral Services: Definition and Mathematical Formulation

To capture the structural and behavioral characteristics of services within a dynamic multi-cloud environment, we define a special class of services, referred to as

Distinct Behavioral Services (DBS). These services deviate from typical invocation patterns and are categorized into three types:

Isolated Services,

Ending Services, and

New Member Services. Their classification is based on the topological features observed within a service invocation graph constructed over a sliding time window. The key mathematical symbols are summarized in

Table 2.

The time window defines the temporal scope for constructing the invocation graph. Here, represents the window size, and t is the current evaluation time. All service invocation records falling within this interval are considered valid when building . This design enables the system to capture short-term behavioral trends while adapting to the dynamic nature of service environments. The value of can be tuned according to service invocation density or domain-specific time granularity.

Let the service invocation graph at time

t be denoted as:

where:

is the set of services active in the time window ;

is the set of directed edges representing invocation relationships.

We define the following DBS categories:

4.1.1. Isolated Service

A service

is classified as

Isolated if it has no interaction with other services in the time window:

Optionally,

s may only invoke itself:

. Isolated Services are completely disconnected from the service invocation graph in the current time window, either due to inactivity or self-invocation only.

4.1.2. Ending Service

A service

is an

Ending Service if it only appears at the terminal position of invocation workflows:

Ending Services act as leaf nodes in invocation workflows, frequently terminating invocation chains, and are categorized based on whether the final invocation comes from the same or a different domain. We further distinguish:

4.1.3. New Member Service

A service

s is considered a

New Member if it has not appeared in any invocation record within the time window:

New Member Services are newly appeared services with no prior records, representing cold-start entities. Each service

s is assigned a behavioral role based on these definitions:

These definitions provide deterministic and reproducible DBS classification based on strict graph-theoretic conditions and forms the basis for downstream service filtering and behavior-aware scoring.

4.1.4. Impact of DBSs on Recommendation Accuracy

The three types of DBS introduce distinct disruptions to recommendation accuracy by interfering with the structural integrity and information flow within invocation topologies. Isolated Services, having no outward or inward connections, receive little to no propagation of collaborative information, resulting in severe score underestimation or exclusion. Ending Services, which often situated at the tail of invocation sequences and act as dead ends in the graph, preventing score propagation to earlier nodes and causing an asymmetry in score distribution. New Member Services, lacking any prior interactions, face absolute cold-start conditions, where traditional history-based models cannot even assign initial values. These conditions lead to information asymmetry in the recommendation system, where certain services are disproportionately undervalued, and introduce scoring imbalance across the pool. Without explicit recognition and compensation of these behavioral anomalies, the system risks biased rankings, missed high-quality candidates, and overall degradation in recommendation robustness. To mitigate these effects, we introduce a DBS identification and structure-aware scoring mechanism that explicitly models the behavioral roles of atypical services. By leveraging the invocation topology and its propagation paths, the mechanism compensates for data deficiencies and behavioral irregularities, ensuring that structurally significant services are assigned more reasonable and reliable scores.

4.2. Service Pool Topology Construction and Initial Scoring

To support behavior-aware analysis and recommendation, we first construct a directed invocation topology from service logs within a given sliding time window. Each invocation record is denoted as:

where user

u invokes service

s at time

t.

From the filtered records, we build a directed service invocation graph:

where:

represents the set of services active during the sliding time window ;

represents the directed edges that denote invocation transitions. If service is followed by in a user session, then an edge is added to .

To compute the preliminary importance or activation level of each service, we define a transition probability matrix

M derived from

:

where

is the frequency of invocation from

to

. This matrix captures the probability that a service call transitions from one service to another.

Let

denote the initial invocation probability vector at time

t. A standard Markov Chain iteration computes the steady-state distribution as:

Once the sequence

converges, the resulting vector represents the base importance score for each service:

Each score

reflects the centrality and activation likelihood of service

s in the current topology. These scores are subsequently adjusted based on DBS classification in the filtering and recommendation stages.

Algorithm 1 is designed to compute the base importance scores for all services within a sliding time window, serving as the initialization for downstream recommendation and filtering tasks. The algorithm transforms raw invocation records into a directed service invocation graph, constructs a transition probability matrix based on invocation frequencies, and propagates service influence scores using Markov Chain dynamics until convergence. The core steps of the algorithm can be interpreted as follows:

| Algorithm 1 Initial Service Scoring via Markov-Based Topology Analysis |

- 1:

Input: Invocation records R, time window - 2:

Output: Base importance score for each service s - 3:

Filter R to obtain records in - 4:

Construct invocation graph - 5:

Count transition frequencies from - 6:

Compute transition matrix - 7:

Initialize vector - 8:

for all do - 9:

- 10:

end for - 11:

for all do - 12:

▹ to avoid zero-score propagation - 13:

end for - 14:

while not converged do - 15:

- 16:

- 17:

end while - 18:

for all do - 19:

- 20:

end for

|

4.2.1. Initial Scoring via Markov Propagation

The Markov-based scoring mechanism operates on the invocation records within a sliding time window. The scoring procedure, as detailed in Algorithm 1, can be interpreted as follows:

Lines 1–4: Filter the raw invocation records R within the window , and construct a directed invocation graph .

Lines 5–6: Count transition frequencies and normalize them into a row-stochastic transition matrix M, where represents the probability of invoking service after .

Line 7: Declare and initialize the score vector .

Lines 8–13: For each service, assign if ; otherwise assign a small constant to avoid zero-score contamination.

Lines 14–17: Perform iterative matrix-vector multiplication until convergence.

Lines 18–19: Assign the converged scores as the base scores for each service.

Line 20: End of loop.

4.2.2. Time and Space Complexity

Let be the number of services, the number of edges, the number of raw invocation records, and K the number of iterations until convergence. The time complexity of each component is:

Lines 1–2: Filtering and graph construction takes .

Line 3: Transition frequency counting takes .

Lines 4–5: Score vector initialization takes .

Line 6: Transition matrix normalization takes theoretically in the worst case, but in the proposed mechanism.

Lines 7–9: Score value assignment for reachable and unreachable nodes takes .

Lines 10–13: Markov propagation iterations takes .

Lines 14–18: Final score assignment takes .

Hence, the total time complexity is:

The space complexity, dominated by the storage of the sparse transition matrix and the score vector, is:

4.2.3. Practical Complexity with Fixed-Invocation Windows

Although the theoretical worst-case complexity may reach during the construction of the transition matrix M in Line 6, this situation only arises when the invocation graph becomes densely connected, leading to a large number of non-zero entries in each row. However, in our design, the sliding window mechanism is based on a fixed number of invocation operations (i.e., ), rather than a fixed time span. This design ensures that the number of recorded invocations per window is controlled, effectively limiting the number of edges and keeping the resulting graph sparse.

As a result, the actual complexity of Markov scoring is , where denotes the number of invocations in the window, K is the number of Markov iterations, and m is the number of active services. Since is fixed and the graph remains sparse across all windows, the matrix M is efficiently computable and the overall scoring process maintains near-linear complexity in practical scenarios.

4.3. DBS-Based Service Filtering Algorithm

After assigning behavioral roles to services based on the topology structure, we apply a DBS-based filtering algorithm to refine the candidate service pool prior to recommendation. This step improves both computational efficiency and semantic relevance by eliminating low-value services and prioritizing behaviorally significant ones.

The filtering process is executed in two phases.

4.3.1. Phase I: Behavioral Role Sorting

In the first phase, each service is examined within its current time-slot topology matrix. The row and column activity vectors are computed to detect null interactions. Services are classified as

Isolated,

Ending, or

New Member based on their invocation activity and, in cases beyond the first time-slot, whether they appeared in previous topologies. This classification is formalized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 DBS Sorting Algorithm |

- 1:

Input: : Topology matrix at time slot k - 2:

Output: , , : Sets of Isolated, Ending, and New Member Services - 3:

for to n do - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

end for - 7:

for to n do - 8:

if then - 9:

if then - 10:

if or then - 11:

- 12:

else - 13:

- 14:

end if - 15:

else - 16:

- 17:

end if - 18:

end if - 19:

end for

|

Algorithm Explanation

Lines 3–6: Filter invocation relationships using the topology matrix , and traverse all service nodes to prepare for behavioral classification.

Lines 7–14: For services with neither incoming nor outgoing edges, determine if they are newly appeared or belong to the first time slot; classify them as New Members or Isolated Services accordingly.

Lines 15–17: For services that are only invoked by others but never invoke any service, classify them as Ending Services.

Complexity Analysis

Let n be the number of services and m be the number of time slots.

Computing the row and column activity vectors takes for each time slot.

The unified iteration over n services involves only constant-time checks and conditional assignments.

Overall time complexity per time slot: .

Total complexity over

m time slots:

4.3.2. Phase II: Ending Role Refinement

In the second phase, the previously detected Ending Services are further divided into

Cross-Domain Ending,

-, or

Universal Ending types by analyzing domain boundaries and inter-domain invocation patterns. This additional semantic distinction is detailed in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 Ending Services Sorting Algorithm |

- 1:

Input: : Topology matrix at time k; : Ending Services set; : Domain of i - 2:

Output: : Cross-Domain Endings; : Universal Endings; : Within-Domain Endings - 3:

for to n and do - 4:

if then - 5:

- 6:

else - 7:

- 8:

end if - 9:

end for - 10:

for each do - 11:

if then - 12:

- 13:

else - 14:

- 15:

end if - 16:

end for

|

Algorithm Explanation

Lines 3–9: For each ending service, examine cross-domain interactions. If it receives calls from services outside its domain, it is labeled as Cross-Domain Ending; otherwise, it is initially assigned to Universal Ending.

Lines 10–15: Within the same domain, further classification determines whether the service is Within-Domain Ending or remains Universal.

Complexity Analysis

The domain-based classification requires a single comparison per service. Assuming domain membership lookup is

, the overall complexity remains:

4.3.3. Impact of Filtering

The results from both phases determine the behavioral status of each service, which is then used to control its inclusion and impact in the recommendation engine. Isolated Services are typically filtered out due to their lack of structural engagement. Ending Services receive score amplification due to their contextual significance, and New Member Services are conditionally retained with neutral or default weights.

This filtering step serves as a lightweight, rule-based pre-processing module that enhances the interpretability and effectiveness of the final recommendation phase without adding substantial computational overhead.

4.4. Sliding Time Window Strategy and Role Judgment

To support dynamic adaptation in service behavior analysis, we implement a

sliding time window strategy that incrementally updates the invocation topology and behavioral roles of services over time, shown in

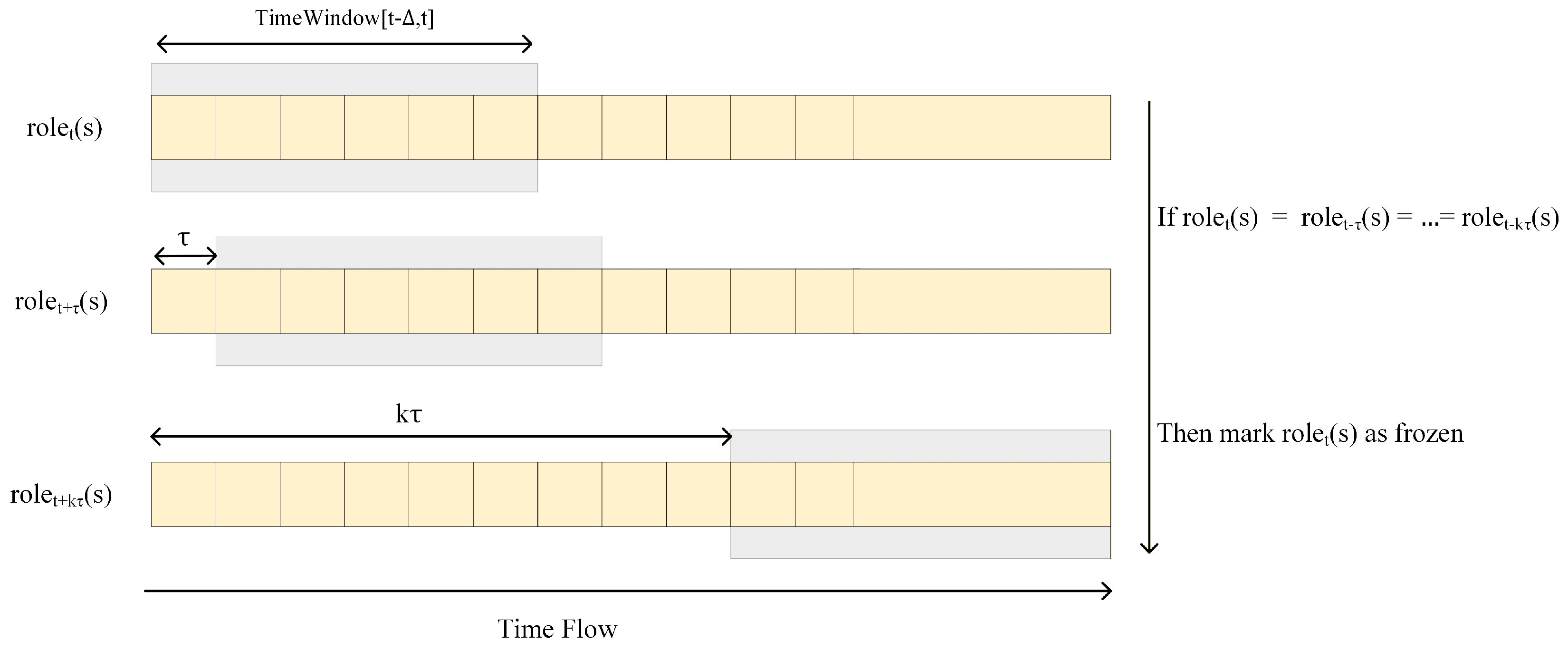

Figure 2, this mechanism enables the system to reflect temporal patterns and evolving invocation contexts without requiring full historical recomputation.

Let denote the window size and the sliding step. At each evaluation timestamp t, the system constructs the service invocation graph using records within the time interval . After computing the behavioral roles for all , the system waits for time units before updating the window to , and recomputes and accordingly.

To capture role evolution and reduce noise due to temporary fluctuations, we define a stability condition that monitors whether a service maintains the same role across multiple consecutive windows. Formally, for a service

s, its role is considered temporally stable if:

where

k is a predefined stability threshold. Once a service satisfies this condition, its role label can be frozen, avoiding unnecessary recomputation or misclassification due to transient invocation patterns.

This sliding mechanism enables the DBS filtering module to dynamically respond to real-time behavior while preserving consistency for structurally stable services. It also allows for efficient incremental updates to recommendation scores when combined with streaming-friendly architectures.

Algorithm 4 maintains the temporal evolution of service behavioral roles using a sliding time window approach. At each update step, it extracts recent invocation records to reconstruct the topology, recomputes behavioral roles using the DBS filtering logic (Algorithms 2 and 3), and checks the stability of each service’s role across previous windows.

Lines 3–5: Initialize the current timestamp and construct the current invocation graph from logs in .

Line 6: Behavioral roles for all active services are recomputed based on current topology and domain-aware DBS rules.

Lines 7–11: For each service, check whether its current role matches the previous k roles over -spaced windows. If so, the role is marked as frozen to avoid redundant updates in future steps.

Line 12–13: Move the time window forward by and repeat the process.

| Algorithm 4 Sliding Window Update Procedure for DBS Role Maintenance |

- 1:

Input: Service logs ; window size ; step size ; stability threshold K - 2:

Output: Updated role labels for each service s - 3:

Initialize - 4:

while new data arrives do - 5:

Filter R within window to construct - 6:

Compute for all using Algorithms 2 and 3 - 7:

for all do - 8:

if then - 9:

Mark as frozen - 10:

end if - 11:

end for - 12:

- 13:

end while

|

Let n be the number of services, m the number of invocation edges within the window, and T the number of total time units (i.e., number of windows processed). The complexity per update step includes:

Filtering records and constructing : , where is the number of logs in window .

Computing roles via Algorithms 2 and 3: (assuming per-slot DBS filtering is linear).

Checking stability for all n services across k prior windows: .

Hence, the time complexity per iteration is:

and the total complexity over

T updates is:

The algorithm maintains:

Thus, the total space complexity is:

The use of role freezing significantly reduces redundant recomputation for behaviorally stable services. Once a service is frozen, its role does not need to be re-evaluated in subsequent iterations unless its topology context changes, thus enhancing performance in dynamic but stable environments.

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Ablation Study on DBS-Aware Recommendation

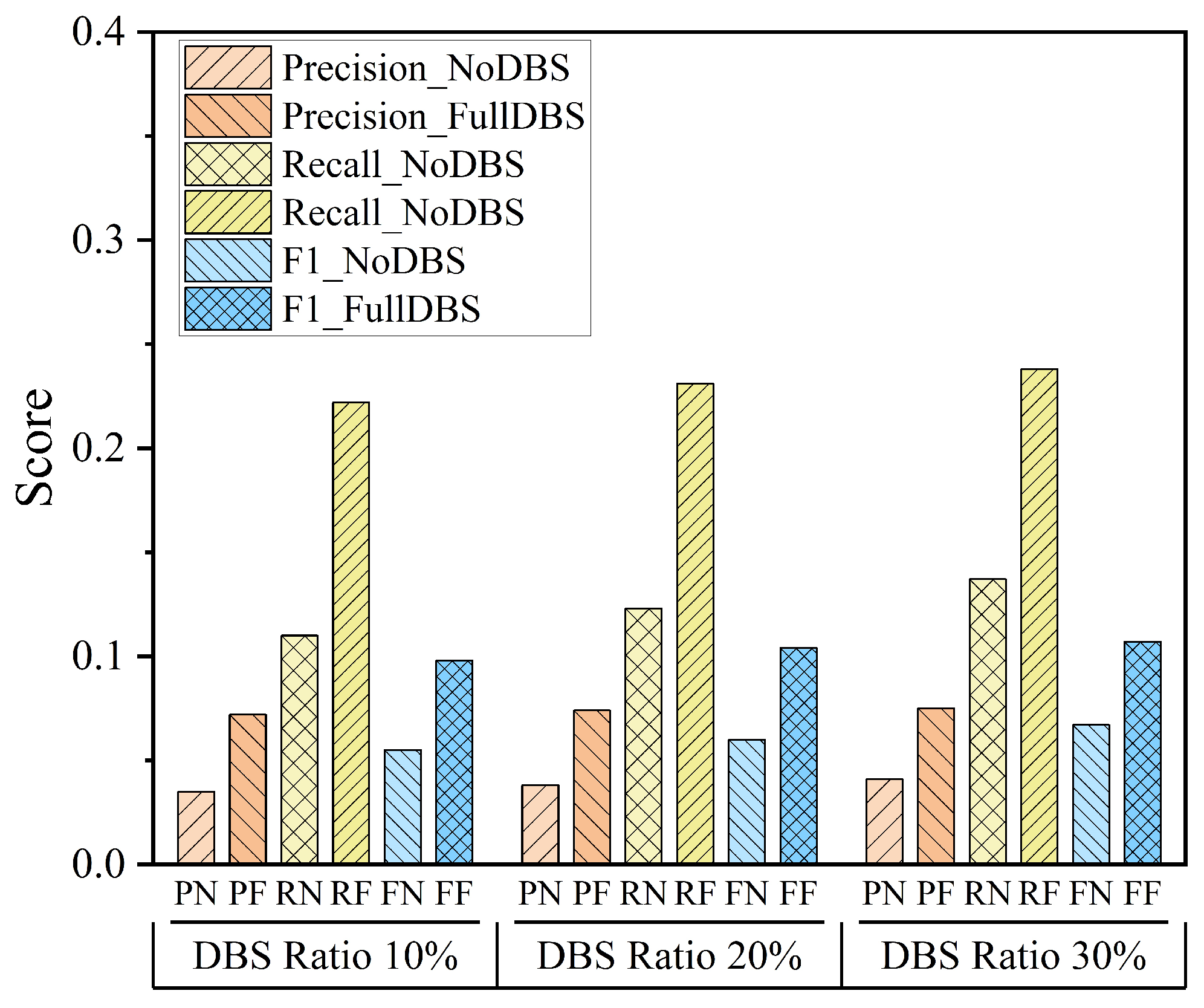

To evaluate the contribution of DBS-aware mechanisms to recommendation performance, we conducted an ablation study comparing two variants: the baseline without DBS filtering (NoDBS), and the full version integrating DBS identification and filtering (FullDBS). The proportion of DBS in the service pool was set to 10%, 20%, and 30%, and evaluation was performed based on Precision, Recall, and F1-score.

As shown in

Figure 3, FullDBS consistently outperforms NoDBS across all metrics and DBS ratios. In particular, the F1-score exhibits the most significant improvement, with relative gains exceeding 130% on average. Precision and Recall also show substantial improvements, generally ranging between 85% and 135%. These results clearly demonstrate that DBS-aware filtering helps eliminate low-quality services and enhance the relevance of recommended items.

Notably, as the DBS ratio increases, the performance gap between FullDBS and NoDBS becomes more pronounced, confirming that proper detection and handling of behavioral outliers (e.g., isolated or newly joined services) is essential for maintaining recommendation accuracy and stability.

6.2. Recommendation Accuracy Under Dynamic Environments

To evaluate the robustness and adaptability of the proposed DBS-based model in such scenarios, we design two complementary simulations:

Dynamic Service Pool: Simulates a gradually expanding set of services, increasing from 1000 to 10,000. This setting tests the model’s ability to score and recommend effectively in the presence of newly added, low-visibility services.

Dynamic User Crowd: Simulates a growing population of service requesters, ranging from 1000 to 10,000. This scenario evaluates how the model responds to shifts in user behavior and the emergence of sparse interaction patterns.

In both simulations, we evaluate five methods: TCF, TREP, MCTSE, GNN, and the proposed method. Precision, Recall, and F1-score are used as performance metrics. All methods share a unified recommendation pipeline to ensure fair comparison, with DBS detection performed uniformly before scoring and ranking.

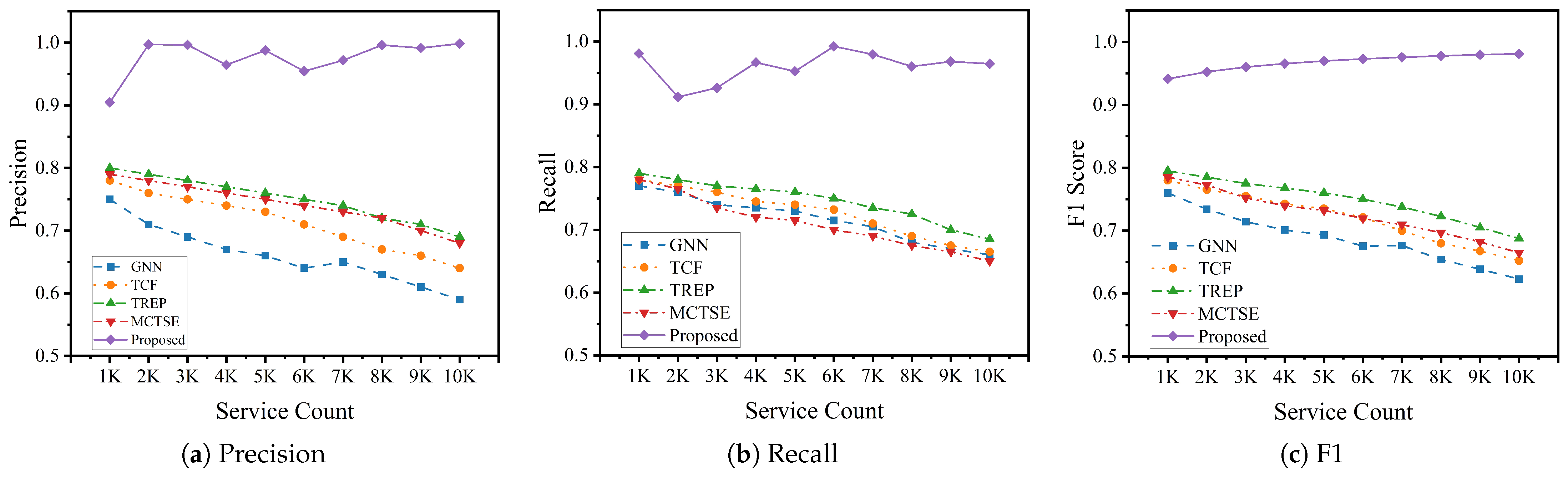

6.2.1. Performance Under Dynamic Service Pool

Shown in

Figure 4, as the number of available services increases, most baseline methods experience a clear decline across all three metrics. TREP and GNN show the most severe degradation, with precision and recall dropping by more than 20%, highlighting their inability to cope with newly added, sparsely connected services. TCF and MCTSE maintain relatively better performance but still exhibit instability. Notably, MCTSE suffers from a gradual decline in precision, likely due to its bias toward highly connected nodes, which becomes problematic when the pool expands and the average connectivity drops.

In contrast, the proposed method demonstrates outstanding robustness. Precision remains above 0.9 even as the pool size increases tenfold, while recall and F1-score show minimal variance. Compared with the best-performing baseline, our model achieves a 46.7% improvement in precision, 42.79% in recall, and 43.76% in F1-score under this setting. This is largely due to the DBS filtering mechanism, which removes unstable or uninvoked services—such as Isolated or Ending types—thereby improving the overall quality of the candidate set and mitigating cold-start effects.

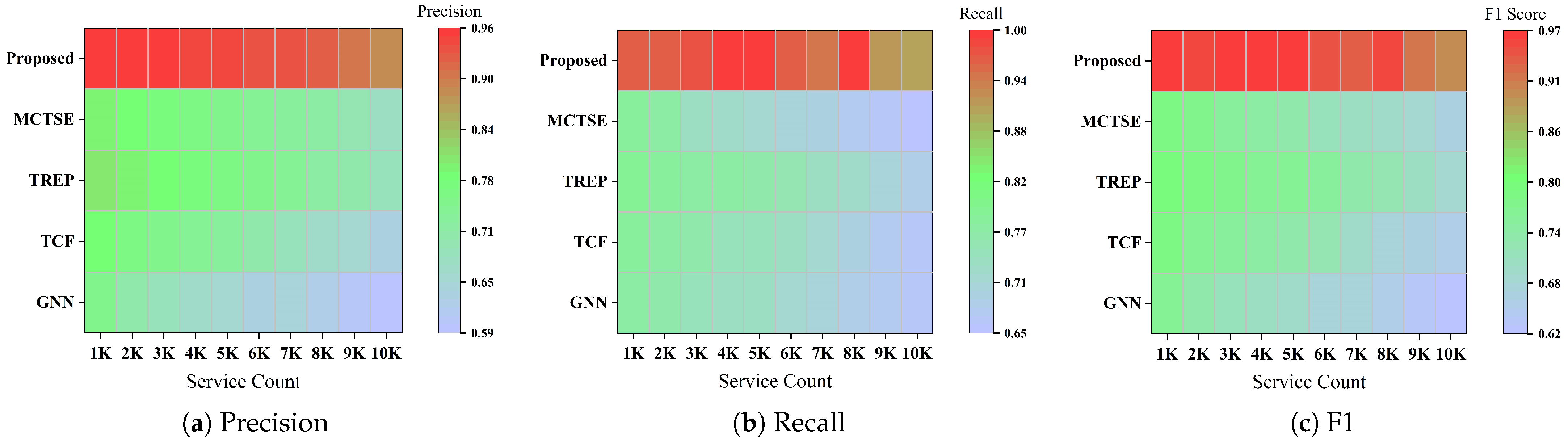

6.2.2. Performance Under Dynamic User Crowd

Figure 5 visualizes the performance trends under user-side dynamics. As user count increases from 1000 to 10,000, most baseline methods show a notable drop in recall. GNN, in particular, falls below 0.65 in high-volume settings, revealing its limited ability to generalize to unseen user behaviors. MCTSE maintains competitive performance in smaller-scale settings but shows increasing volatility in recall and F1-score as the user base grows. This suggests that while it handles structural noise reasonably well, it does not adapt effectively to behavioral variation introduced by dynamic users.

In contrast, the proposed method maintains high and stable performance, with all three metrics remaining above 0.9 across the entire user range. Notably, the model delivers a 40.5% increase in precision, 41.2% in recall, and 39.62% in F1-score compared to the best-performing baseline in this setting. This robustness is attributed to two key factors: (i) DBS filtering helps stabilize the service graph regardless of user fluctuation, and (ii) the Markov scoring ensures smooth and fair score propagation even when user-service interactions are sparse or newly formed.

6.3. Temporal Role Stability Under Sliding Window

6.3.1. Window Size Sensitivity

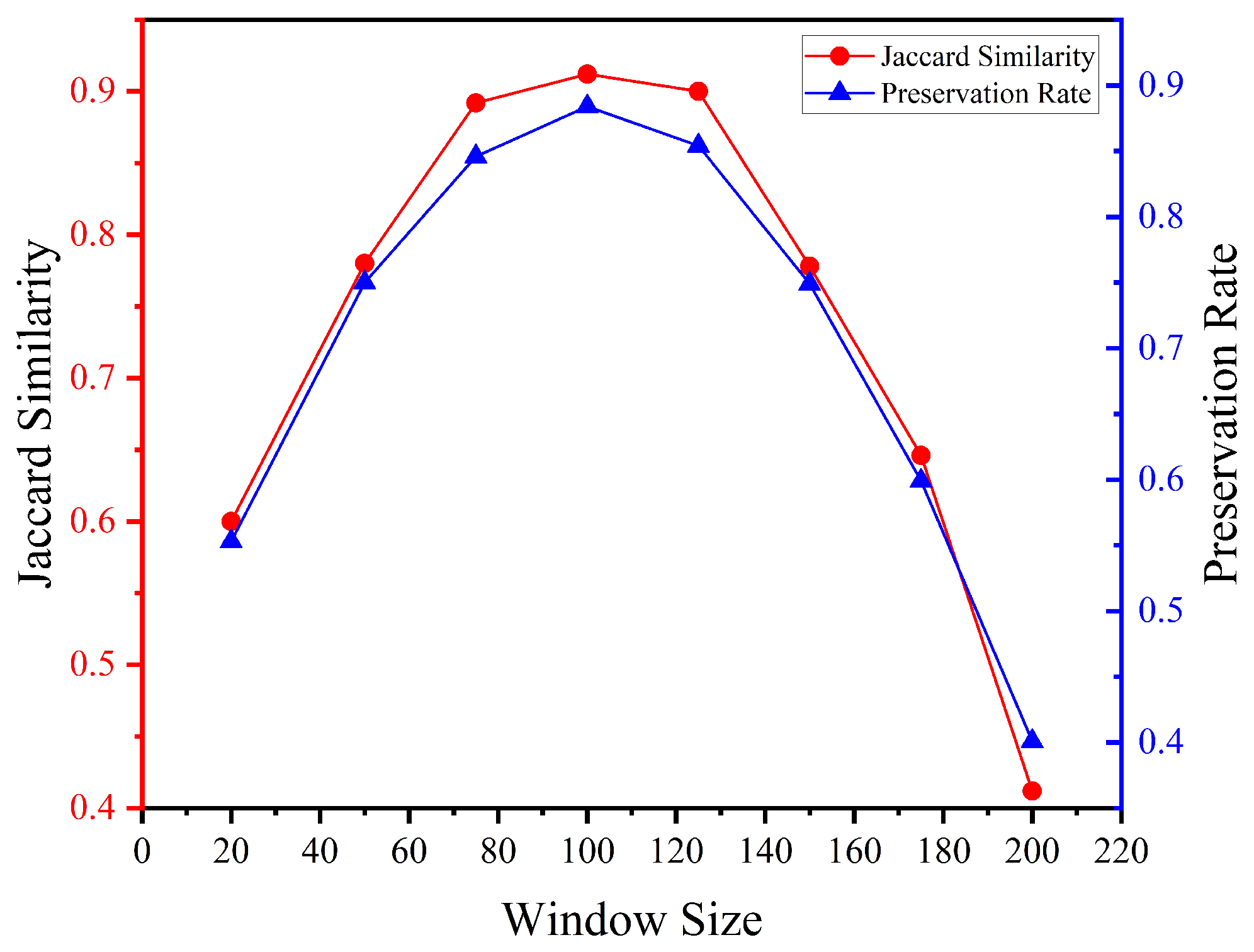

To further evaluate the stability of service behavior identification under different sliding window configurations, we conducted a sensitivity analysis based on window size. Instead of using fixed time intervals, we adopted the number of invocation operations as the unit of segmentation to mitigate density imbalance caused by usage fluctuations. Specifically, we simulated a service pool with 100 services and 1000 total invocations, and divided the timeline into windows of varying sizes: 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, and 200 operations per window. Within each window, the system identified behavioral roles for services (i.e., Isolated, Ending, and New Member), and we computed the role consistency across adjacent windows. Two metrics were used for evaluation:

As shown in the

Figure 6, both metrics peak at a window size of 100, reaching 0.91 and 0.88 respectively. These results indicate that a window size of 100 offers optimal stability for role classification, and it is thus adopted as the default configuration in subsequent simulations.

6.3.2. Temporal Role Stability

This simulation evaluates the temporal stability of recommendation results when applying the proposed sliding time window strategy and behavioral role freezing. We aim to test whether filtering services based on stable DBS roles reduces noise and prevents recommendation list volatility over time.

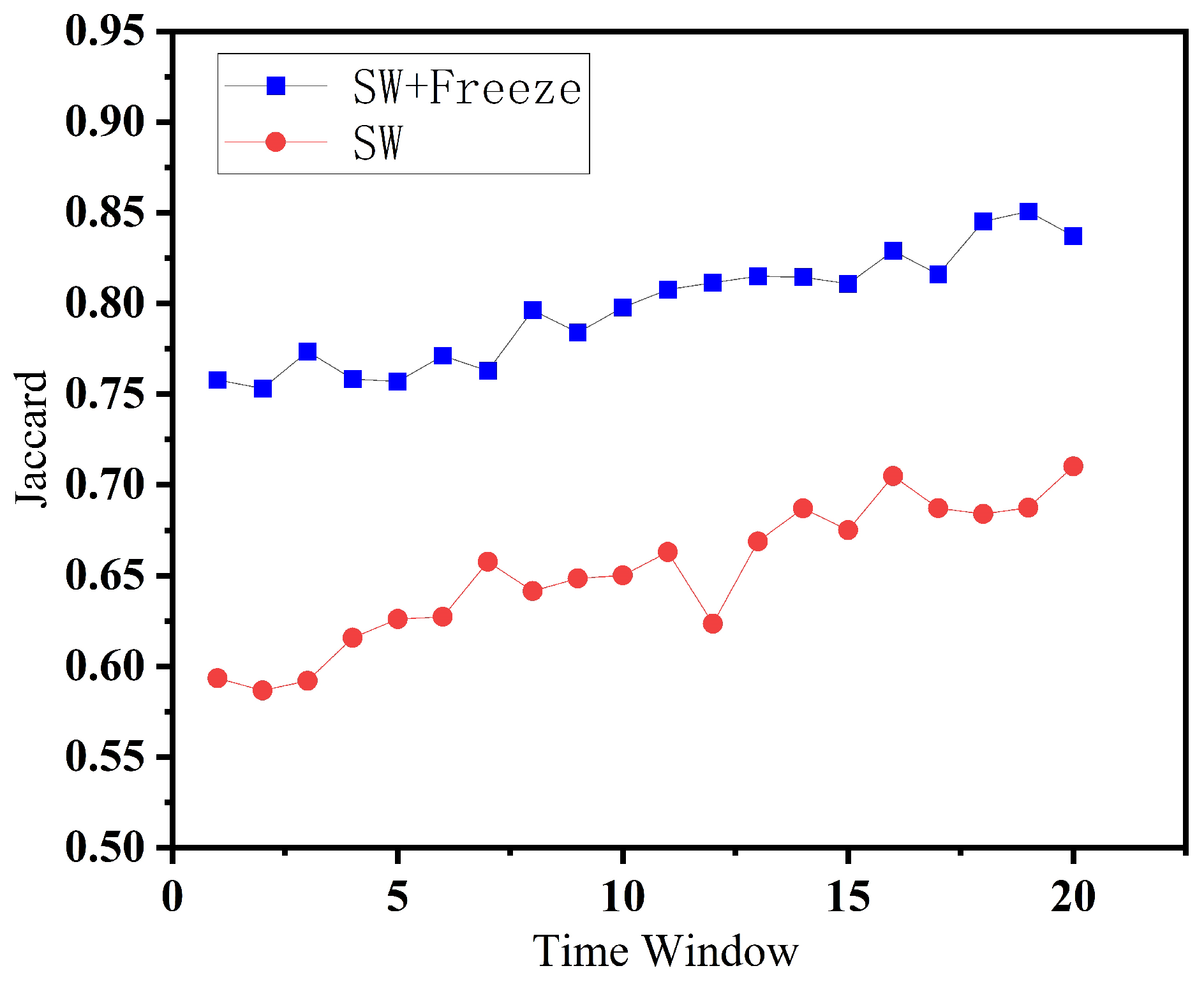

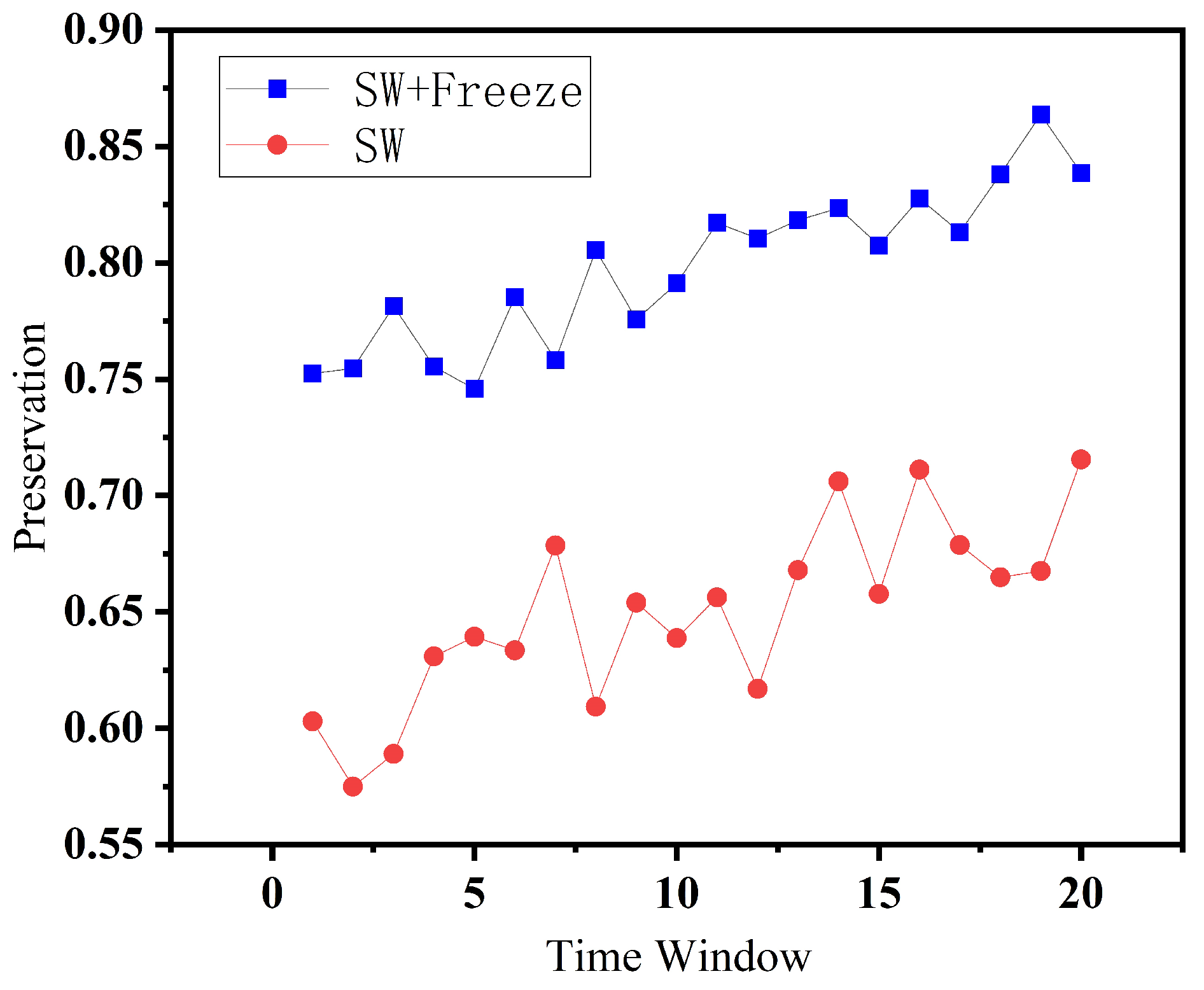

We segment the service invocation data using a sliding window strategy based on operation counts rather than time intervals, aligning with the findings of our window size sensitivity analysis. Specifically, we set the window size to 100 service invocations and a sliding step size of 25 invocations. For each window, the system constructs an invocation graph and generates Top-N recommendations for active users (). We compare two variants of the system across 20 consecutive windows and evaluate the consistency of recommendation outputs.

Two variants of the system are compared:

Ours (Sliding Windows(SW) + freeze): we refer to a common strategy in temporal smoothing and behavioral stability analysis, where consistency observed across three or more consecutive observations is typically considered a strong indicator of stable behavior. Services whose roles remain unchanged for consecutive windows are frozen, and their roles are reused in future filtering.

Ours (Slinding Windows (SW)): Role judgment is recomputed independently in every window, without considering temporal consistency.

Figure 7 shows the Jaccard@10 scores over 20 sliding windows. The method with role freezing consistently achieves higher overlap (typically above 0.75), while the version without freezing fluctuates at lower values (around 0.62). This indicates that the freezing strategy stabilizes the recommendation list across time.

In

Figure 8, we visualize the Preservation@10 metric. Similar to Jaccard, the method with role freezing shows higher preservation rates, indicating that previously recommended services are more likely to persist in subsequent windows. This reinforces the idea that the role stability mechanism prevents premature removal of useful services due to transient behavior shifts. Both metrics confirm that our sliding window strategy with behavioral role freezing improves the temporal stability of recommendations. Compared to the setting without freezing, our proposed strategy achieves a 22.85% improvement across sliding windows, demonstrating its effectiveness in maintaining recommendation stability over time. It helps retain high-confidence services and avoids fluctuations caused by unstable DBS classifications, resulting in more consistent and reliable recommendation behavior over time.

6.4. Coverage Under Data Sparsity

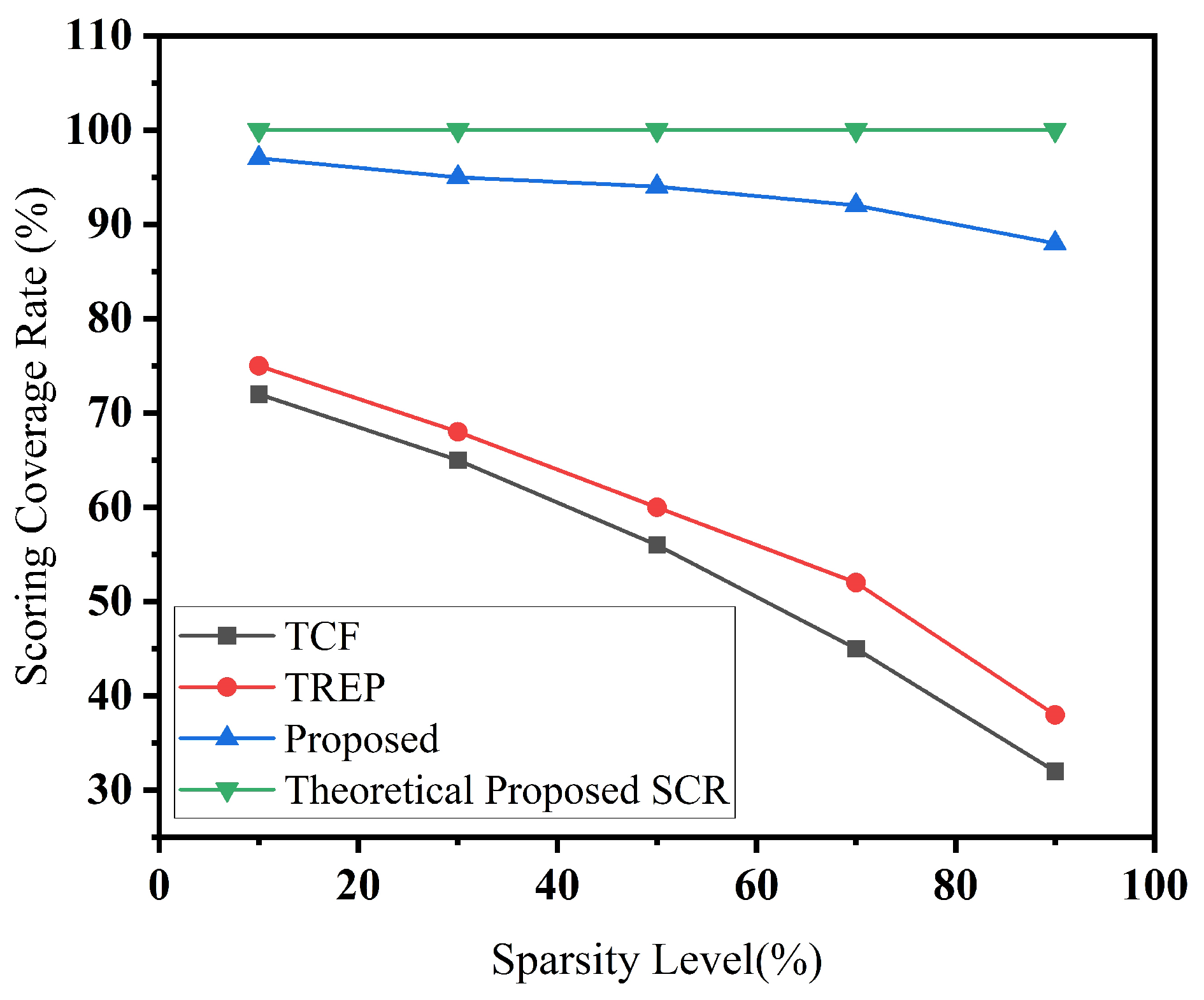

We evaluate scoring coverage under five predefined sparsity levels: {10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%}, representing increasingly severe data sparsity in the service invocation records. For each sparsity level, a corresponding proportion of invocation data is randomly removed from the original dataset to simulate incomplete service histories. Based on the resulting topology, we apply the scoring process and calculate the Scoring Coverage Rate (SCR), which measures the proportion of services receiving non-zero scores. A higher SCR indicates better robustness to sparse data conditions.

The results are shown in

Figure 9. As the sparsity level increases, both TCF and TREP exhibit consistent drops in scoring coverage. For example, at 90% sparsity, their SCRs decrease to 32% and 38%, respectively, indicating that a large portion of services fail to receive valid scores due to insufficient invocation data or limited connectivity.

In contrast, our proposed Markov Chain-based method demonstrates significantly stronger resilience. Even under the most extreme sparsity condition (90%), it achieves an SCR of 88%, and steadily improves as more data is available—reaching 97% when sparsity drops to 10%. This consistent high coverage is aligned with the theoretical guarantee of our method, which ensures complete score propagation as long as the service topology remains connected and irreducible.

To highlight this point, we include a horizontal reference line representing the theoretical upper bound of 100% SCR, derived from the homogeneous irreducibility of our Markov Chain model. The minor gap between the actual and ideal coverage stems primarily from occasional topological fragmentation during random edge removal. Nevertheless, our approach consistently outperforms TCF and TREP, showing clear superiority in handling sparse service environments.

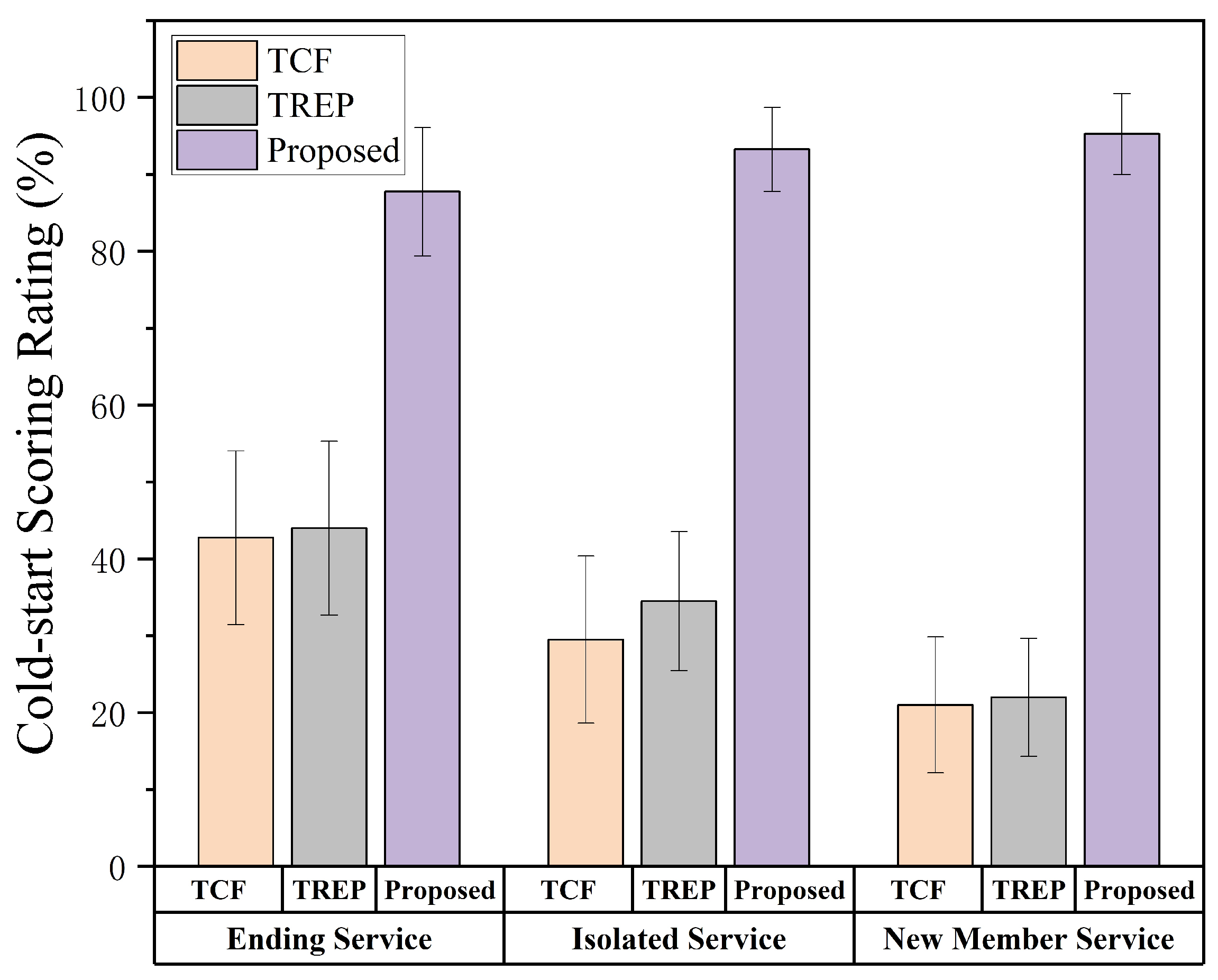

6.5. Cold-Start Scoring Rate on DBS Services

DBS exhibit strong cold-start characteristics due to their limited or nonexistent invocation histories. Traditional recommendation methods, such as Collaborative Filtering (TCF) and trust-based approaches (TREP), often fail to assign scores to these services, resulting in poor coverage and ineffective recommendations. To assess the cold-start handling capability of our model, we define the Cold-Start Scoring Rate (CSR) as the proportion of DBS services receiving non-zero scores. All three types of DBS services are considered, and the CSR is evaluated across 20 randomized simulations to ensure statistical stability. The compared methods include: (i) TCF, (ii) TREP, and (iii) our proposed Markov Chain-based scoring method.

The average CSR results and standard deviations over 20 experimental runs are summarized in

Figure 10. Our proposed model significantly outperforms baseline methods across all DBS categories. In particular, it achieves a CSR of 95% on New Member services, whereas TCF and TREP score only 22% and 23%, respectively. Similarly, for Isolated and Ending services, our method maintains CSR above 88%, while the baselines drop below 45%.

These results validate the model’s strong cold-start robustness, which stems from its reliance on the topological structure of the service invocation graph rather than historical co-occurrence. Furthermore, the low standard deviation across all runs demonstrates the consistency of the scoring mechanism. Although the theoretical CSR of our model is expected to reach 100% due to its homogeneous and irreducible Markov Chain properties, slight deviations may still occur. These are primarily caused by fully disconnected nodes in the DBS set or by numerical thresholds that treat extremely low scores as zero. Nevertheless, the achieved performance remains superior in both coverage and stability.

6.6. Statistical Significance Test

To further validate the reliability of our experimental results, we conducted a paired t-test to examine whether the performance improvements of the proposed method over baseline approaches are statistically significant. The test was performed on the F1-scores obtained across all device count settings under both experimental scenarios: Dynamic User Crowd and Dynamic Pool.

Specifically, we compared the Proposed framework against four representative baselines (GNN, TCF, TREP, and MCTSE) using paired samples from identical experimental configurations. Shown in

Table 5, the resulting

p-values are consistently far below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.05 (in the order of

to

), confirming that the observed improvements are not due to random variation but are statistically significant.

This statistical validation reinforces the conclusion that the proposed method consistently and significantly outperforms existing baselines across diverse experimental settings, providing stronger evidence for the robustness and generalizability of our framework.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary of Contributions

In this paper, we introduced the concept of Distinct Behavioral Services (DBS) and proposed a structural classification framework that identifies special service types such as New Member, Isolated, and Ending services based on invocation topology. These services typically suffer from extreme sparsity or lack of co-invocation records, posing serious challenges for conventional recommendation systems. To address this, we designed a unified scoring model that integrates DBS detection with a Markov Chain-based scoring mechanism. This approach ensures that even under cold-start or sparse conditions, services can receive consistent and topology-aware scores. The proposed framework is scalable and domain-agnostic, making it suitable for complex multi-cloud service environments.

Extensive simulations were conducted under four perspectives: recommendation accuracy, stability under sliding time windows, scoring coverage under data sparsity, and cold-start performance on DBS services. Results confirm the superiority of our approach over existing collaborative filtering and topology-based methods. In particular, our method consistently achieves higher precision, recall, and F1 score, while maintaining robustness in dynamic user and service environments.

7.2. Limitations and Future Work

Although the proposed DBS-aware recommendation framework demonstrates strong performance and robustness across different dynamic scenarios, several limitations remain.

- (1)

Dataset Generalizability.

The Santander Smart City dataset reflects urban IoT-style service interactions, which are not fully equivalent to real-world multi-cloud service invocation ecosystems. While it provides representative dynamic behaviors and invocation patterns, the absence of genuine cross-cloud workflow traces may limit the direct generalizability of the evaluation results.

- (2)

Topology Reconstruction Assumptions.

The framework assumes that invocation relations can be accurately extracted from logs to construct topology matrices. In large-scale multi-cloud deployments, log completeness, monitoring granularity, or privacy restrictions may introduce missing or noisy topology information.

- (3)

Temporal Window Sensitivity.

The sliding-window mechanism involves selecting a fixed window size. Although experiments demonstrate stable performance across different settings, extreme fluctuations in service pool dynamics may require adaptive or learned window sizes.

Future work will focus on collecting real multi-cloud workflow traces, designing adaptive temporal windows, and exploring learning-based topology extraction to further improve the applicability of DBS-aware recommendation in large-scale cloud environments.