1. Introduction

Wireless non-contact sensing is a technology that uses the propagation characteristics of wireless signals to invert the human behavior occurring in the propagation environment. It has a wide range of application scenarios in elderly care [

1,

2,

3,

4], health supervision [

5,

6,

7], and daily behavior recognition [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Wireless non-contact sensing technology shows great potential for application. However, traditional models are often difficult to adapt to the changing incremental data environment, and the entire model needs to be retrained to maintain accuracy. This model not only consumes a lot of computing resources, but also seriously affects the real-time response speed of the model. In particular, when it is necessary to quickly identify emerging human behaviors or environmental changes, the lag in model updating may become a key factor restricting the effectiveness of the technology application.

The root cause of this problem is the lack of models with both high recognition accuracy and good adaptability in complex dynamic environments. Existing machine learning models generally have limitations: traditional models such as Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), and Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) have high recognition accuracy but lack sufficient generalization ability; although the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm has strong generalization ability, its basic recognition accuracy often has difficulty coping with the demands of practical application. Therefore, designing and implementing a base model that can simultaneously have strong generalization ability and high recognition accuracy has become a core problem that needs to be solved nowadays. After determining the basic model, another important challenge is how to design an incremental training strategy to achieve the optimal balance between training efficiency and model performance. This not only needs to consider the knowledge retention and update mechanism in the incremental process but also needs to balance the relationship between the training time cost and the incremental training model recognition accuracy to ensure that the system can adapt to environmental changes stably and efficiently.

In order to solve the above challenges, this paper proposes a WIS method. This method can ensure high-precision recognition and fast response of the original action while introducing new actions. The WIS method has two main components: the base sensing module, NFFCN, and the incremental training module, NFFCN-RTST. Compared with the traditional NCM classifier, the NFFCN module only needs a small number of comparisons on each node, and the classification accuracy is significantly improved by implicitly encoding the category hierarchy. The NFFCN-RTST module uses the RTST incremental training strategy. This training is different from the common methods of ULS and IGT in that it not only updates the statistics of the leaf nodes, but also further optimizes the previously learned splitting function, resulting in more accurate and stable incremental training results.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) The base sensing module NFFCN is proposed; NFFCN is an improved method based on Random Forest. This method has the characteristics of high computational efficiency and optimized classification structure. Its classification effect is comparable to models such as RF and GDBT, but NFFCN has better generalization ability and can better adapt to complex wireless sensing environments.

(2) The incremental training module NFFCN-RTST is proposed, which adopts the RTST incremental training strategy. It can ensure the accurate recognition of new actions at a lower cost, while maintaining the recognition accuracy of the original actions and realizing a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

(3) A large number of experiments on rRuler and Stan WiFi datasets are conducted to verify the robustness and real-time response speed of the WIS method in different scenarios and to provide new solution ideas for incremental training in the field of wireless non-contact sensing.

2. Related Work

2.1. Non-Contact Human Activity Recognition

With the rapid advancement of wireless sensing technologies, non-contact human activity recognition (HAR) has evolved from camera- or wearable-based methods toward wireless and intelligent sensing approaches. Radar, Wi-Fi, and reconfigurable intelligent surface (RIS) technologies have become central to this evolution. Luo [

12] provided a systematic overview of radar-based HAR, emphasizing challenges such as multipath interference and environmental sensitivity. Ye et al. [

13] further proposed a deep metric ensemble learning approach for cross-person activity recognition using Wi-Fi signals, achieving significant improvements in generalization.

To address privacy concerns in wireless sensing, Wei et al. [

14] developed CIU-L, a class-incremental and machine-unlearning passive sensing system for human identification, demonstrating strong adaptability in dynamic environments. In the realm of hybrid sensing, Khan [

15] introduced TriSense, combining RFID, radar, and USRP to enhance sensing reliability, while Gu et al. [

16] applied millimeter-wave radar to healthcare robots for fine-grained gesture recognition.

In addition, the integration of RIS into beyond-5G sensing has opened new research avenues. Hashima et al. [

17] pioneered the use of reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RISs) for activity recognition in beyond-5G sensing, demonstrating enhanced robustness and adaptability through programmable signal reflections. Later, Rizk et al. [

18] evolved this idea into the 6G-based RISense framework, which integrates deep learning and RIS-assisted propagation to further improve recognition performance in multipath and low-SNR environments. Dang and Cheffena [

19] designed a multifunctional single-antenna platform for non-contact human–machine interaction, demonstrating the feasibility of embedded sensing systems.

Despite these advances, existing systems still face limitations in generalization, cross-domain adaptability, and real-time performance. Most approaches rely on fixed data distributions and retraining when new activities or subjects appear, which is computationally expensive and impractical for continuous deployment.

2.2. Incremental Learning for Adaptive HAR

To overcome the limitations of static models, incremental learning (IL) and continual learning (CL) have been introduced to enable adaptive and lifelong human activity recognition. Pan and Zhu [

20] proposed an adaptive prompt-driven few-shot class-incremental learning framework using radar data, which alleviates catastrophic forgetting in small-sample incremental scenarios. Cai et al. [

21] reviewed generalizable HAR systems and highlighted that most existing methods lack domain-invariant representations and unified benchmarks for incremental evaluation.

Wei et al. [

22] conducted a comprehensive survey of Wi-Fi-based human identification systems, pointing out that incremental learning approaches are rarely optimized for large-scale, real-world deployments. Moreover, Hassanpour and Yang [

23] emphasized that multimodal fusion (Wi-Fi, radar, vision) remains underexplored, and joint modeling across modalities could further enhance adaptability and robustness.

The integration of IL with emerging wireless paradigms such as RIS and edge computing is still nascent. Current models either retrain full networks or rely on replay-based strategies, both of which are computationally costly. As a result, maintaining accuracy while supporting real-time adaptation remains an open challenge.

The studies summarized above report strong accuracy or robustness in Wi-Fi, radar, and RIS settings. Yet most pipelines do not provide a lightweight class-incremental path suitable for edge devices. They rely on full or near-full retraining, replay buffers, or specialized hardware. Update time and memory budgets are rarely bounded, and privacy-aware deployments cannot always keep historical data. These gaps make low-latency class-incremental adaptation difficult in practice.

In summary, recent studies on non-contact HAR and incremental learning reveal significant progress in wireless sensing and adaptability. However, challenges remain in real-time incremental adaptation, cross-domain generalization, and efficient retraining under dynamic environments.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes the Wireless Incremental Sensing model, which integrates a nearest-feature-fusion classifier with an RTST strategy. WIS achieves efficient class-incremental learning and real-time adaptability in wireless non-contact sensing, bridging the gap between accuracy, generalization, and computational cost.

3. Method

3.1. Basic Sensing Training Module NFFCN

3.1.1. Nearest Class Mean Classifier

The Nearest Class Mean classifier (NCM) [

24] is an efficient classification method. The idea is to compute the average feature of each class, then assign a test sample to the nearest class prototype. Let the class set be

with

and class index

. The decision rule and prototype estimator are

Here

denotes the distance between sample

and the class prototype

. In traditional NCM classification, the Euclidean distance is usually used for the measure. However, the Euclidean distance only considers the linear distance between samples and ignores the correlation between samples. To better reflect such correlations, we use the Mahalanobis distance [

25]:

And parameterize the metric as

with

and

. We denote the induced distace by

. Here M denotes the metric matrix that defines the learned distance measure, and W is the linear projection that maps the input features into a lower-dimensional space for metric shaping. Mahalanobis distance whitens the feature space through the inverse covariance of each class. It reduces the influence of directions with large variance and removes cross-feature correlation. With this distance, the prediction probability is

The maximum-likelihood objective and its gradient are given in Equations (5) and (6).

Here

represents the log-likelihood of the class probability under the current model. Where

and

. To further enhance classification, we adopt a low-rank parameterization of the metric so that

simultaneously performs linear projection and metric shaping, revealing low-dimensional structure in the data:

Here is the learnable linear projection; when , performs low-rank embedding and metric shaping, while recovers the Euclidean case.

3.1.2. NFFCN Model

NFFCN is an improved method based on Random Forest (RF) [

26], which uses NCM as the splitting function. Its advantages are follows:

High computational efficiency: NFFCN uses only some categories for decision making, reducing computational complexity.

Optimize the classification structure: Improve the classification speed and implicitly encode the category hierarchy through the binary splitting strategy.

During training, at node

let

be the set of samples that reach this node and let

be the set of class labels present in

. For each

, compute the class centroid

Then, each centroid

is randomly assigned to the left or right child nodes. And define the classification function:

where

is the

-th canonical basis vector with a 1 at position

and 0 elsewhere, so

is the one-hot encoding of the predicted class. The predicted class index

is obtained by minimizing the Mahalanobis-induced distance between the sample and the centroids:

Compared with standard RF, NFFCN can effectively deal with high-dimensional data and nonlinear relationships, reduce dependence on complex metric learning, and improve classification accuracy and computational efficiency.

3.2. Incremental Sensing Training Module NFFCN-RTST

As shown in

Figure 1, we first train NFFCN on the initial class set and then evaluate its classification performance for actions in wireless contactless perception. To visualize the internal decision process of NFFCN,

Figure 1 illustrates the initial structure and probability details of the model. At each split node, a small subset of class centroids is preserved, and their Voronoi cells partition the local feature space. Each colored dot represents the centroid of a different class (e.g., green, yellow, orange). The straight lines between them denote the decision boundaries that separate regions of influence for each centroid. When a sample

is input, it is routed to the child node corresponding to its nearest centroid according to the Mahalanobis-induced distance.

The mini bar charts beneath each panel show the leaf-level class-posterior vector at the reached leaf. Each bar indicates the posterior probability associated with one class, and the bar height reflects the likelihood of the corresponding class given the current node’s statistics. In this initial state, no incremental update is performed—the structure and posteriors represent the initial training configuration of the NFFCN model. Throughout all mini bar charts, x denotes the class index and y denotes the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

3.2.1. Incremental Training Sensing Model of ULS

In the incremental training strategy of updating leaf statistics (ULS) [

27], we assume that a multi-class RF has been trained for the class set

. In

Figure 2, the model is then expanded by passing the training samples of the new class

through the existing trees and updating the class probabilities

. This procedure updates only leaf statistics. It does not change any split function or the tree topology. Therefore, the initial forest must be reasonably expressive so it can adapt to new categories. When the model is initialized, sufficient training data must be provided to ensure that the tree can cover the distribution of all data. Otherwise, the fixed structure may overfit the initialization data and harm later increments, because a poor hierarchy cannot be corrected by ULS.

Specifically, when a new class

is added, for each class

the leaf posterior

is updated. The update uses the counts observed at the leaf and Laplace smoothing. After adding

, for each class k in the updated set

, the leaf posterior is updated as

where

is a leaf index and

is a class index. Here

is the number of class-

samples routed to leaf

(cumulative after the update), and

is the total count at leaf

. Since we use Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra-Trees) for initialization, the forest can be used directly for classification. The decision rules are as follows:

where

is the predicted label of the

-th tree for sample

. The mode operator returns the most frequent label.

After training the initial forest, new class samples are passed through the existing trees. Only the leaf-level class posteriors

are updated; split functions and the tree topology remain unchanged. In

Figure 2, the colored dots again denote the centroids of three example classes—green, yellow and orange—and the lines depict the fixed local partitions induced by these centroids. The mini bar charts below each panel visualize the class-posterior vector stored at the reached leaf. Across panels, the boundaries remain unchanged, while the heights of the bars change, illustrating that ULS updates the statistics

only.

Algorithm NFFCN-ULS incrementally updates a pretrained NFFCN forest without changing any split function or tree topology. For each incoming labeled sample from new classes or new batches, the sample is routed through the fixed tree using the nearest-centroid rule. At the reached leaf , the stored class-posterior vector is updated only at the leaf level using the counts observed at this increment with smoothing, as in Equation (11). This procedure is repeated for all new samples; no node is split or merged, and no global retraining is performed. During inference, a test sample is routed to a leaf and the tree prediction is obtained from the updated posteriors; the forest output is the mode over trees.

We employ NFFCN-ULS as a fast class-incremental mechanism to incorporate new categories under tight compute budgets. It enables adding classes without revisiting past data and without rebuilding the tree structure, while adapting the leaf-level probabilities

to the new distribution. This makes the model practical for continual scenarios where frequent full retraining is infeasible. NFFCN-ULS pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 NFFCN-ULS |

Input: initial labeled set D0; incoming labeled batch D+; current forest F; Laplace ε > 0

Y = set of seen class labels; K = |Y|

Output: updated forest F′ |

1: if F = ∅ then

2: F ← Train NCM-RF on D0 using centroid-based splits

3: initialize each leaf.count over Y ← labels(D0); K ← |Y|

4: end if

5: //merge new classes

6: Y ← Y labels(D+); K ← |Y|

7: for each tree T in F do

8: for each leaf ℓ in T do

9: EXTEND_COUNTS_TO_K(ℓ.count, Y) //append zeros for new labels only

10: end for

11: for each (x, y) in D+ do

12: ℓ ← DESCEND_BY_CENTROID(T, x)

13: ℓ.count[y] ← ℓ.count[y] + 1

14: end for

15: for each leaf ℓ in T do

16: for each c Y do

17: ℓ.P[c] ← (ℓ.count[c] + ε)/(∑{k ∈ Y} ℓ.count[k] + ε·K )

18: end for

19: end for

20: end for

21: F′ ← F

22: return F′ |

3.2.2. Incremental Training Sensing Model of IGT

Incrementally Grow Tree (IGT) differs from ULS. As shown in

Figure 3, if a new class has enough samples to reach a leaf, the tree continues to grow. Previously learned split functions remain unchanged, but new splits can be added to adapt to distribution shifts caused by the new class. Under IGT, the new split is trained on the combined data

, whereas the original splits were learned from the initial class set

. Therefore, it can be assumed that the new training samples are extracted from a linear distribution rather than from a rough initial distribution. In our experiments, new classes appear in random order; this tests how the method behaves when incoming data may be unrelated to previously observed classes.

Unlike ULS, IGT allows the tree structure to expand when a new class provides sufficient samples. As illustrated in

Figure 3, incoming samples are first routed through the existing tree; if a leaf accumulates enough evidence of a novel class, a new split is learned from the combined data

and attached to that leaf, while all previously learned split functions remain unchanged. In the figure, the colored dots denote class centroids. The straight segments inside each circle are the decision boundaries. The mini bar charts below the circles visualize the leaf-level class-posterior vector

for the shown node. Items drawn in blue are created at the current increment, whereas black elements were learned earlier and are kept fixed.

3.2.3. Incremental Training Sensing Model of RTST

The main difference between retrain subtree (RTST) and ULS and IGT is that, as shown in

Figure 4, RTST not only updates the statistics of leaf nodes but also updates the previously learned split functions. As shown in

Figure 4, colored dots mark class centroids. Blue elements indicate parts created at the current increment; black elements were learned earlier and remain fixed. The mini bar charts summarize the leaf-level class-posterior vector

; higher bars mean higher probabilities. The left-to-right sequence shows how the tree grows as new classes arrive. ULS and IGT cannot converge to a forest trained on

because they do not revisit internal splits learned on the initial set

. RTST addresses this by selecting a set of internal nodes and treating them as temporary roots. It prunes their descendants, then regrows each pruned subtree using both the stored references and the new increment data. During regrowth, split functions are re-estimated, leaves are reinitialized, and the posteriors

are recomputed in the affected subtrees. After RTST finishes, inference routes a test sample to a leaf and aggregates tree votes, as defined in Equation (12). NFFCN-RTST pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 2.

In summary, RTST assumes a multi-class forest has been trained on the class set . When a new class arrives, the training samples are passed through the forest to update leaf statistics, and selected subtrees are retrained: internal nodes are chosen, their descendants are pruned, and the subtrees are regrown on using the stored references plus the new data. This enables the model to refresh outdated decision boundaries where needed without rebuilding the whole forest.

To control the retraining cost, we select only a fraction of candidate subtrees at each increment. When , the tree is fully retrained and the process is no longer incremental. When , no subtree is retrained; structural changes, if any, come from local growth (IGT-like behavior), otherwise only ULS-style leaf updates occur. For , RTST balances accuracy gains from refreshed splits against computation.

We deploy RTST when simple leaf statistics updates (NFFCN-ULS) are not sufficient and when unbounded structural growth (NFFCN-IGT) would over-fragment the tree. RTST refreshes outdated decision boundaries only where needed, adapts to distribution shifts introduced by new classes, and restores separability in local regions without rebuilding the whole forest or revisiting all historical data.

| Algorithm 2 NFFCN-RTST |

Input: initial labeled set D0; incoming labeled batch D+; number of trees T; refresh ratio π;

leaf min size μ; candidates per split m. Y = set of seen class labels; K = |Y|; ε > 0

Output: updated forest F′ |

1: if F = ∅ then

2: F ← ∅; Y ← labels(D0); K ← |Y|

3: for t = 1..T do

4: S ← BOOTSTRAP(D0)

5: tree ← BUILD_TREE_BY_CENTROID(S, μ, m)

6: INIT_LEAF_COUNTS(tree, Y); INIT_LEAF_POSTERIORS(tree, ε)

7: PERSIST_REF(tree, S) //store sample refs reaching each leaf

8: F ← F {tree}

9: end for

10: end if

11: //merge new classes if any

12: Y ← Y labels(D+); K ← |Y|

13: for each tree in F do

14: EXTEND_LEAF_COUNTS_TO_Y(tree, Y) //append zeros for new labels only

15: //fast leaf update on new batch

16: for each (x, y) in D+ do

17: ℓ ← DESCEND_BY_CENTROID(tree, x)

18: ℓ.count[y] ← ℓ.count[y] + 1

19: APPEND_REF(ℓ.ref, x)

20: end for

21: for each leaf ℓ in tree do

22: for each c Y do

23: ℓ.P[c] ← (ℓ.count[c] + ε)/(∑{k Y} ℓ.count[k] + ε·K )

24: end for

25: end for

26: //RTST: selective subtree refresh

27: q ← EVAL_NODE_QUALITY(tree, D+) //e.g., high impurity or low margin

28: S_low ← SELECT_LOW(q, ratio = π)

29: for each node n S_low do

30: S_old ← FETCH_BY_REF(n.ref)

31: S_new ← SAMPLES_REACH_NODE(tree, n, D+)

32: S_loc ← S_old S_new

33: PRUNE_TO_LEAF(tree, n)

34: n ← REPLACE_SUBTREE(tree, n, BUILD_TREE_BY_CENTROID(S_loc, μ, m))

35: REFRESH_LEAF_STATS(n, Y, ε) //re-init posteriors within subtree

36: end for

37: end for

38: F′ ← F

39: return F′ |

4. Experiments

4.1. Simulation Test Bed

All experiments were conducted in a controlled simulation test bed implemented in Python 3.8.0 to evaluate the proposed NFFCN-based incremental learning algorithms. The test bed does not generate synthetic data; instead, it uses two publicly available datasets: rRuler [

28] and Stan WiFi [

29]. These datasets provide real or pre-recorded wireless sensing measurements that are used as the base training set

and the incremental batches

for continual learning experiments.

Each configuration was repeated five times with distinct random seeds. We report all metrics as mean ± standard deviation across these runs. The simulation environment is responsible for sequentially feeding the data streams to the model, applying noise perturbations when required, and logging the performance metrics. All experiments were performed on a workstation with an Intel i7 CPU (3.6 GHz), 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA Tesla V100s 32G.

4.2. Datasets

4.2.1. rRuler Dataset

rRuler [

28] is a publicly available RSS dataset with an open address on GitHub. The dataset was collected by Huang et al. in the indoor laboratory area. Each experimenter, Huang, Ren, Sun, and Guo, would perform seven actions in three different links (15, 20, and 26). The length of each action of the original RSS data is different, and the minimum length is as follows: fall-Forward-657, fall-Left-438, fall-Right-263, jump-167, run-Vertical-425, walk-Hori-909, walk-Vertical-1238. We used the seven actions of the experimental participant Huang mentioned above. At the same time, the training set, test set, and verification set are divided according to the ratio of 50:10:5.

4.2.2. Stan WiFi Dataset

Stan WiFi [

29] is a publicly available CSI dataset with an open address on GitHub. The dataset is collected in the indoor office area and contains six different activity data: Lay-down, Fall, Walk, Run, Sit-down, and Stand-up. These activities were performed by six experimenters, where each person performed 20 times per activity and the generated data size was about 17 Gb. In this experiment, we selected the data of these seven actions completed by one of the experimenters.

4.3. Analysis of NFFCN Experimental Results

4.3.1. Accuracy Analysis

- (1)

Accuracy Analysis on rRuler Dataset

In order to verify the algorithm accuracy of each classifier in non-incremental mode, this study uses NFFCN classifier, DT classifier, GBDT classifier, RF classifier, SVM classifier, and KNN classification, respectively. The rRuler dataset is verified, and the confusion matrix of each action is shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 reports, for each classifier, a confusion matrix on the rRuler dataset under the non-incremental setting. Rows list the ground-truth classes and columns list the predicted classes. A bright diagonal indicates correct predictions, while off-diagonal mass reveals which classes are confused with each other.

RF achieves the best overall accuracy at 90.0 percent. DT reaches 88.6 percent and GBDT reaches 88.0 percent, both with strong diagonals and few errors outside the diagonal. NFFCN reaches 87.1 percent, and its matrix shows a concentrated diagonal similar to tree-based baselines, which indicates that routing and leaf-posterior estimation are competitive in this static evaluation. SVM reaches 77.1 percent and KNN reaches 72.9 percent, both with more dispersed off-diagonal mass. The main residual errors appear between actions with similar motion patterns, for example, walk versus run and left-fall versus right-fall. These matrices therefore summarize both overall accuracy and class-level error structure, which we use as a baseline reference for the incremental studies in the following sections.

On the rRuler dataset, RF achieves a slightly higher accuracy in the non-incremental setting. This is expected because RF grows each tree from bootstrapped samples and performs strong feature bagging, which yields highly expressive decision boundaries when the training set is fixed. NFFCN routes samples by nearest class centroids and estimates class posteriors at leaves, which can be marginally less expressive when different actions overlap in feature space. The advantage of NFFCN appears once the learning becomes incremental. NFFCN updates leaf posteriors in place, grows structure only when sufficient evidence accumulates, and retrains subtrees only where boundaries become outdated. This design avoids full retraining, removes the need to store past data, and keeps update latency and memory usage low while preserving accuracy on previously seen actions.

Section 4.4 reports the incremental results that support this behavior and shows that the gap observed in the static case does not translate into a disadvantage under continual updates.

- (2)

Accuracy analysis on Stan WiFi dataset

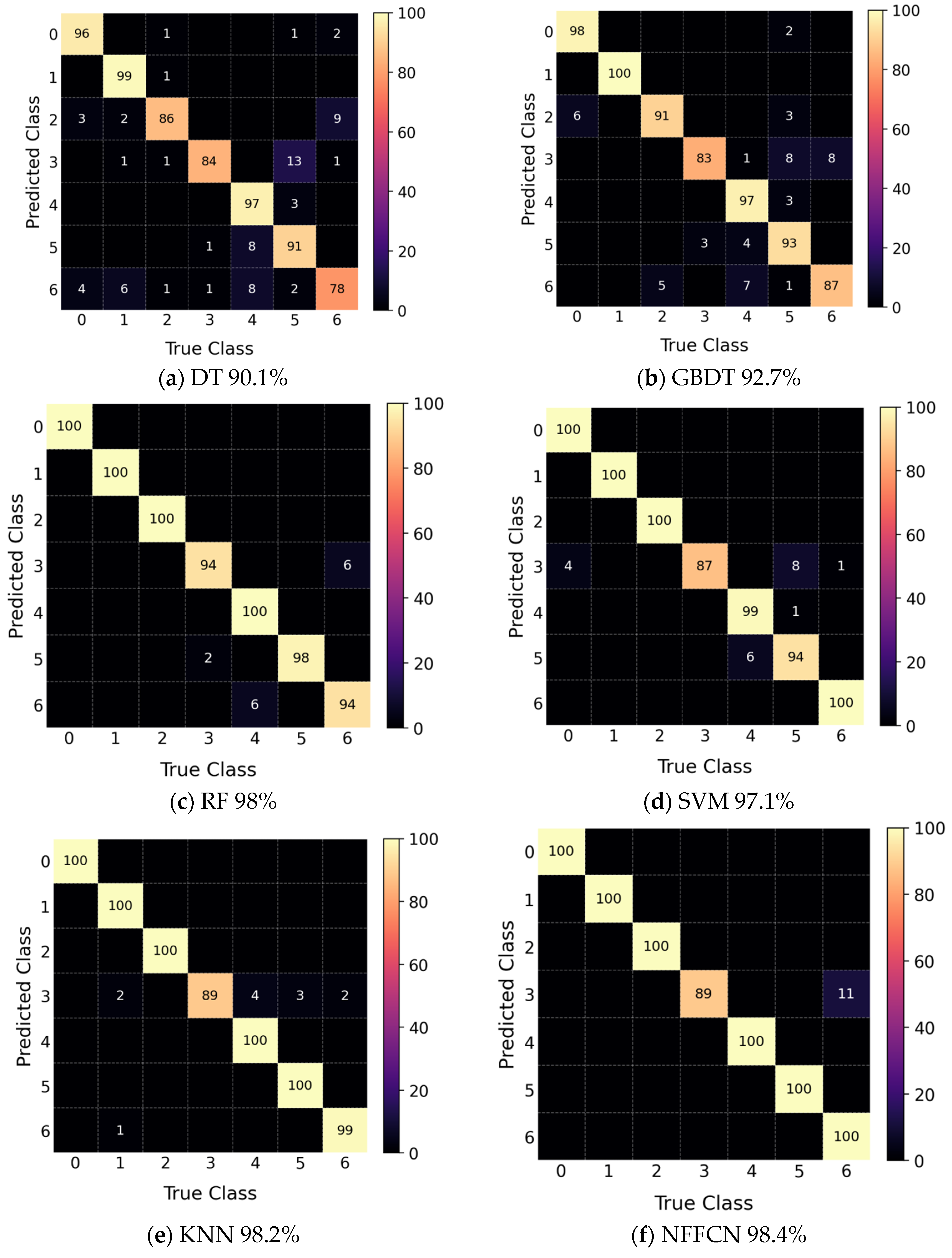

In order to further verify the correctness of NFFCN, this study performs the same verification on the Stan WiFi dataset. The classification confusion matrix of each action on the Stan WiFi dataset is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 reports, for each classifier, a confusion matrix on the Stan WiFi dataset under the same non-incremental protocol as in

Figure 5. Rows list the ground-truth classes defined in

Section 4.2.2 and columns list the predicted classes. Each cell records the size of test samples assigned to that pair and the color bar encodes the magnitude. A strong diagonal indicates correct predictions; off-diagonal mass reveals which activities are confused.

NFFCN reaches the highest overall accuracy at 98.4 percent. KNN follows with 98.2 percent and RF with 98.0 percent, all three showing almost purely diagonal matrices with only a few small off-diagonal entries. SVM achieves 97.1 percent and keeps most mass on the diagonal, while GBDT achieves 92.7 percent and DT 90.1 percent, both with noticeably more dispersion. The remaining errors mainly occur between activities with similar dynamics, for example, walk versus run or sit-down versus stand-up, which explains the small clusters of off-diagonal counts. These matrices therefore confirm that the Stan WiFi data are highly separable and they show that NFFCN is competitive with the strongest baselines while providing the mechanism we use later for incremental updates.

Through comprehensive comparison, NFFCN is more suitable for coarse-grained (RSS) and fine-grained (CSI) wireless eigenvalue classification than the SVM classifier and KNN classifier. When classifying RSS data, the accuracy is slightly lower than that of the same type of RF, DT, and GBDT classifiers, but it is superior to other classifiers on the CSI dataset. Considering that NFFCN has better generalization ability than RF, DT, and the GBDT algorithm, in this paper, the NFFCN algorithm is selected as the basic algorithm of incremental training.

4.3.2. Analysis of NFFCN Execution Efficiency

The efficiency of algorithm execution is an evaluation index to evaluate the computational cost of wireless non-contact sensing. Therefore, this study trains NFFCN with DT, GBDT, RF, SVM, and KNN on the rRuler and Stan WiFi datasets and records the time of model training and prediction test set for the seven actions of the dataset. The results are reported as mean ± standard deviation across multiple independent runs with distinct random seeds and class orders. The computational cost of NFFCN and the other five multi-class classifiers on rRuler and Stan WiFi datasets is shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Based on

Table 2, NFFCN trains in 2.2480 ± 0.0793 s on average. It is 55.0 s faster than GBDT, 18.5 s faster than SVM, 1.0 s slower than KNN, and 1.6 s slower than RF. For tests, NFFCN needs 0.2413 ± 0.0062 s per test pass. KNN requires 0.1968 ± 0.0047 s. Tree and margin methods return in only a few milliseconds: RF 0.0191 ± 0.0005 s, SVM 0.0028 ± 0.0002 s, and GBDT 0.0032 ± 0.0004 s.

Based on

Table 3, NFFCN trains in 4.8421 ± 0.18 s on average. It is 15.67 s faster than GBDT and 4.55 s slower than DT. Compared with SVM and KNN, it is 4.55 s and 4.79 s slower, respectively. It is 3.46 s slower than RF. For tests, NFFCN requires 0.0642 ± 0.0031 s per test pass. It is 0.118 s faster than KNN. Tree and margin models return more quickly: RF 0.0138 s, SVM 0.0039 s, GBDT 0.0036 s, and DT 0.0011 s.

In summary, the computational cost of NFFCN is a compromise between the same and different classifiers. Considering that it has better generalization ability than SVM, KNN, RF, DT, and GBDT classifiers, this study chooses the NFFCN algorithm as the basic algorithm of incremental training.

Combining accuracy and efficiency, NFFCN is a multi-classifier with low computational cost and high accuracy. This performance makes it more suitable for incremental sensing. Therefore, this study selects NFFCN as the base model of the incremental sensing model.

4.4. Analysis of NFFCN-RTST Experimental Results

4.4.1. Accuracy Analysis

- (1)

rRuler Dataset

We evaluate NFFCN-RTST together with five multi-class baselines, NFFCN-ULS, NFFCN-IGT, SVM-RTST, SVM-ULS, and SVM-IGT, on the rRuler dataset. Training starts with K = 4 classes, and the remaining classes are added incrementally. The columns “4–7” in

Table 4 indicate the number of classes seen so far. We report the step-wise top-1 accuracy during the incremental process as e across repeated runs with distinct seeds and class orders.

As detailed in

Table 4, the NFFCN-RTST classifier demonstrates superior performance on the rRuler dataset. Initially, with four classes, it achieved an accuracy of 97.4 ± 0.6%. This was notably higher than all other models, outperforming NFFCN-ULS and NFFCN-IGT by 2.2% and 5.3%, respectively, and surpassing the SVM-based classifiers by a margin ranging from 5.1% to 19.3%.

Crucially, after three incremental learning stages to include a total of seven classes, NFFCN-RTST maintained a robust accuracy of 87.1 ± 1.1%. In this final configuration, it continued to outperform its NFFCN counterparts, exceeding the accuracy of NFFCN-ULS and NFFCN-IGT by 3.1% and 4.8%. The performance gap with the SVM models became even more pronounced; NFFCN-RTST showed an accuracy advantage of 14.0% over SVM-RTST, 21.1% over SVM-IGT, and a substantial 35.8% over SVM-ULS, highlighting its effectiveness in mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

- (2)

Stan WiFi Dataset

Table 5 reports step-wise accuracy on the Stan WiFi dataset from K = 3 to K = 7. After four increments, K equals 7, NFFCN-RTST achieves 95.9 ± 0.7%. This exceeds NFFCN-IGT at 95.1 ± 1.0% by 0.8 percentage points and exceeds NFFCN-ULS and SVM-ULS by 45.7 and 49.6 points, respectively. It remains close to the SVM variants with updates, trailing SVM-RTST and SVM-IGT by 1.6 and 1.3 points.

4.4.2. Analysis of NFFCN-RTST

For the incremental training multi-classification algorithm, the model training time is an evaluation index to evaluate the computational cost of wireless non-contact sensing. Therefore, this study trains the NFFCN-RTST and five other multi-class classifiers on the rRuler and Stan WiFi datasets, trains a forest on the predefined k initial classes, and then incrementally adds other classes one by one.

As presented in

Table 6, the NFFCN-RTST classifier demonstrates a significant computational advantage over the SVM-RTST and SVM-IGT classifiers. When incrementally adding the three new classes, NFFCN-RTST consistently reduced the calculation time. In contrast, NFFCN-RTST exhibited a slightly higher calculation cost compared to the NFFCN-ULS and SVM-ULS models, with the time difference ranging from approximately 0.01 s to 1.2 s across the incremental learning stages. Comparison with NFFCN-IGT revealed a variable trend: NFFCN-RTST was notably faster when adding the fifth class, but became marginally slower in the subsequent two steps.

The computational costs for the six classifiers on the Stan WiFi dataset are detailed in

Table 7 The data indicates that NFFCN-RTST offers a substantial improvement in efficiency over the SVM-based incremental training models. Specifically, during the final incremental step, NFFCN-RTST was approximately 44.2 s and 48.8 s faster than SVM-RTST and SVM-IGT, respectively. This highlights its scalability as the number of classes increases. Conversely, when compared to the ultra-low-cost NFFCN-ULS and SVM-ULS models, NFFCN-RTST required more time, with the computational overhead increasing from approximately 1.7 s to 3.7 s over the four incremental stages. A more variable relationship was observed with NFFCN-IGT; NFFCN-RTST was slower when adding the fourth, fifth, and seventh classes, but demonstrated a slight speed advantage when adding the sixth class.

In summary, NFFCN-RTST is a multi-classifier with a compromise between accuracy and training time. Its base model NFFCN only needs to be compared several times on each node, and the learning cost is low. On any specific node, only a small number of classifications are used to further accelerate and obtain a weak classifier. Combined with RTST, by storing a reference to the training sample in the leaf, the training data of K class can be effectively reused with the new class k′ of the newly created leaf node, and the incremental training strategy of updating the statistical information can be updated. It is suitable for systems that must deal with dynamic environments where new classes frequently occur.

4.5. Discussion

4.5.1. Why We Favor NFFCN for Incremental Learning

NFFCN provides three coordinated update modes. The ULS mode refreshes leaf posteriors with constant cost per sample. The IGT mode expands the structure only at leaves that receive enough new class evidence, which prevents uncontrolled growth. The RTST mode refreshes outdated splits in a targeted way, which restores separability without rebuilding the whole forest. The model does not require rehearsal memory and does not access past samples, which fits privacy-sensitive and resource-constrained deployments. These properties make NFFCN a practical backbone for class-incremental recognition, even if a static RF is slightly higher on one dataset.

4.5.2. Why SVM-Based Methods Collapse Under Incremental Training

SVM decision boundaries are globally coupled. When a new class arrives, the optimal margins shift for many classifiers. Without rehearsal data or full retraining, the margins drift toward the current increment and the calibration for old classes degrades. In one-vs-rest schemes, adding a class requires renewed negative evidence for all existing classifiers; if this evidence is absent, strong bias appears and errors accumulate. Kernel SVMs also tend to acquire more support vectors over time, which raises memory and computation and further limits stable updates. Under an incremental protocol with limited memory and no full retraining, these factors lead to rapid performance collapse.

4.5.3. Why RTST Outperforms ULS and IGT in Accuracy

RTST achieves higher accuracy because it repairs outdated internal splits where routing errors originate. It selects low-quality or highly uncertain internal nodes, prunes their descendants, and regrows the affected subtrees using the current increment. During regrowth, it re-estimates both the internal splits and the leaf posteriors, which restores local separability and prevents error propagation down the tree. The rest of the forest remains unchanged, so stability is preserved while the problematic region adapts. The update ratio π bounds the extent of retraining and balances cost against accuracy. Over long incremental sequences, this targeted refresh keeps routing clean and yields higher average accuracy than ULS and IGT.

4.5.4. Practical Deployment Considerations and Limitations

Two practical points matter most in deployment. Environmental changes can shift the feature distribution. When the shift is small, ULS refreshes the leaf posteriors in real time so the model adapts quickly. When a leaf repeatedly mixes classes, IGT grows a small split at that location to sharpen the boundary. For larger changes, RTST retrains only the affected subtree so the rest of the forest remains unchanged and full retraining is avoided. Edge devices have limited compute and energy. We schedule updates by urgency: run ULS continuously for low-cost adaptation, batch a few IGT updates during idle periods, and reserve RTST for maintenance windows. This schedule preserves accuracy while keeping memory and time use within the device’s capability. Cross-device variation, evolving channel noise, and multi-user activity are not addressed in this study. We list them as future work and will evaluate them under controlled conditions.

4.5.5. Relation to Existing Studies and State-of-the-Art Context

Although this study does not include a direct numerical comparison with existing works, the proposed NFFCN framework conceptually aligns with recent advances in incremental and continual learning research. The results presented here highlight that the NFFCN variants (ULS, IGT, and RTST) achieve performance and adaptability comparable to state-of-the-art incremental models while maintaining significantly lower computational cost. This demonstrates the framework’s practical value for real-time sensing scenarios where frequent retraining is infeasible.

5. Conclusions

This study tackles two practical obstacles of wireless-signal based action recognition under class-incremental learning, namely accuracy degradation after new classes arrive and real-time constraints. We build a unified forest-based framework with three update modes, NFFCN-ULS for leaf statistics refreshing, NFFCN-IGT for controlled structural growth, and NFFCN-RTST for selective subtree retraining. The framework updates posteriors at leaves using a principled rule, routes samples by nearest centroids, and aggregates trees by majority vote. The design lets the model absorb novel classes without revisiting historical data and without mandatory full retraining.

Experiments on two public datasets show that the proposed approach reaches the accuracy of strong batch learners while keeping the update cost small. For the coarse-grained rRuler data, the non-incremental baselines confirm the competitiveness of our forest, where NFFCN stays close to Random Forest and clearly surpasses SVM and KNN. For the fine-grained Stan WiFi data, the forest remains highly separable and NFFCN delivers near-perfect diagonals in the confusion matrices. Under the incremental protocol, the proposed WIS system maintains high average accuracy, around 87 percent on rRuler and around 95 percent on Stan WiFi, which is comparable to batch training performed with access to the full data. At the same time the incremental procedures reduce computation by about twenty-three to fifty percent because they avoid global retraining and limit updates to the affected regions of the forest.

Compared with similar incremental tree and streaming classifiers reported in the literature, which typically either update only leaf counts or grow unbounded structures, our three-mode design balances stability and plasticity. NFFCN-ULS offers the lowest cost when distributions are stable, NFFCN-IGT introduces new splits only when evidence accumulates, and NFFCN-RTST refreshes outdated boundaries in a targeted manner. This combination requires neither rehearsal memory nor access to past samples, which makes it well suited to privacy-sensitive and resource-constrained deployments. The method improves scalability and operational efficiency while maintaining accuracy, providing a practical solution for class-incremental recognition with RSS and CSI signals.

Overall, the proposed NFFCN framework extends existing incremental forest models by integrating three complementary update strategies that achieve near-batch accuracy with significantly lower computational cost. This unified design advances the current state of continual learning toward more efficient and privacy-friendly wireless sensing applications.

6. Future Work

There are still some problems to be solved in the WIS wireless non-contact sensing increment training technology proposed in this paper, such as the following:

- (1)

Transfer learning. The environment has a great influence on the model of human action recognition. The model constructed in the current study is only applicable to this environment. Once the environment changes, re-learning is necessary.

- (2)

Group perception. The current incremental training recognition system can only recognize one person ‘s action, and the problem of how to achieve multi-target simultaneous detection still needs to be further explored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W.; data curation, X.Z. and W.L.; investigation, X.Z. and W.L.; methodology, G.W. and Y.W.; resources, H.S. and Y.D.; software, G.W. and Y.W.; supervision, H.S. and Y.D.; visualization, W.L.; writing—original draft, G.W. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, G.W. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Project of the Department of Education of Jilin Province (JJKH20250945KJ). Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Project—Youth Growth Science and Technology Plan Project (20220508038RC), New Generation Information Technology Innovation Project of China University Industry, University and Research Innovation Fund (2022IT096), Jilin Province Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Project (2023QN31), NaturalScience Foundation of Jilin Province (No.YDZJ202301ZYTS157, 20240601034RC, 20240304097SF), and Innovation Project of Jilin Provincial Development and Reform Commission (2021C038-7). Research on Key Technologies for Simultaneously Deceiving the Human Visual System and Deep Learning Models in Image steganography (JJKH20250945KJ).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Q. Frequency-Diverse Imaging and Sensing: Electromagnetic-Information Principle, Dispersion Engineering, and Applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Electromagn. Antennas Propag. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, R.; Iranmanesh, S.; Naeim, A.; Benharash, P. Editorial: Bench to bedside: AI and remote patient monitoring. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1584443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. RT-Fall: A Real-Time and Non-contact Fall Detection System with Commodity WiFi Devices. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2017, 16, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lee, G.-H.; He, H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Katabi, D. RF-Based Fall Monitoring Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. Arch. 2018, 2, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wu, D.; Xiong, J.; Yi, E.; Gao, R.; Zhang, D. FarSense: Pushing the Range Limit of WiFi-based Respiration Sensing with CSI Ratio of Two Antennas. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 3, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Wang, S.R.; Dai, J.Y.; Li, H.-D.; He, Y.; Cheng, Q. Multiperson Respiration Detection: A Digital Programmable Metasurface Analysis Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 39116–39129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhalvandi, L.; Karamzadeh, S. Advances in Non-Contact Human Vital Sign Detection: A Detailed Survey of Radar and Wireless Solutions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 27833–27851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xue, H.; Miao, C.; Wang, S.; Lin, S.; Tian, C.; Su, L. Towards 3D Human Pose Construction Using WiFi. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom), London, UK, 21–25 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Q.; Pan, M.; Wang, J. Practical Device-Free Gesture Recognition Using WiFi Signals Based on Metalearning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; An, X.; Liu, Q. Human Activity Recognition Based on Non-Contact Radar Data and Improved PCA Method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qu, L. Research on Cross-Scene Human Activity Recognition Based on Radar and Wi-Fi Multimodal Fusion. Electronics 2025, 14, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F. Applications and Challenges of Radar-Based Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Smart Internet of Things (SmartIoT), Shenzhen, China, 14–16 November 2024; pp. 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Xu, S.; He, Z.; Yin, Y.; Ohtsuki, T.; Gui, G. Non-Contact Cross-Person Activity Recognition by Deep Metric Ensemble Learning. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. CIU-L: A Class-Incremental Learning and Machine Unlearning Passive Sensing System for Human Identification. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2024, 103, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z. TriSense: RFID, Radar, and USRP-Based Hybrid Sensing System. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; He, X.; Fang, G.; Xia, F. Millimeter Wave Radar-based Human Activity Recognition for Healthcare Monitoring Robot. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashima, S.; Rizk, H.; Yamaguchi, H. The Future of Beyond 5G Sensing: Transforming Activity Recognition with Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Activity and Behavior Computing (ABC), Oita/Kitakyushu, Japan, 29–31 May 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, H.; Hashima, S. RISense: 6G-Enhanced Human Activity Recognition System with RIS and Deep LDA. In Proceedings of the 2024 25th IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), Brussels, Belgium, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Cheffena, M. Multifunctional Sensing Platform Based on Single Antenna for Noncontact Human–Machine Interaction and Environment Sensing. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2024, 72, 7664–7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Zhu, W.-P. Adaptive Prompt Driven Few-Shot Class-Incremental Learning for Human Activity Recognition with Radar Modality. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Guo, B.; Salim, F. Towards Generalizable Human Activity Recognition: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, W.; Ning, S.; Lin, W.; Li, N.; Lian, B.; Sun, X.; Zhao, J. A Survey on WiFi-based Human Identification: Scenarios, Challenges, and Current Solutions. ACM Trans. Sen. Netw. 2025, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, A.; Yang, B. Contactless Vital Sign Monitoring: A Review Towards Multi-Modal Multi-Task Approaches. Sensors 2025, 25, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Z.; Li, R.; Kim, H.; Sanner, S. Supervised Contrastive Replay: Revisiting the Nearest Class Mean Classifier in Online Class-Incremental Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3584–3594. [Google Scholar]

- De Maesschalck, M.; Jouan-Rimbaud, D.; Massart, D.L. The Mahalanobis distance. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2000, 50, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristin, M.; Guillaumin, M.; Gall, J.; Van Gool, L. Incremental Learning of Random Forests for Large-Scale Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- rRuler Dataset. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/sunhy0521/RF-gesture-recognition (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Stan WiFi Dataset, GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/ermongroup/Wifi_Activity_Recognition (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Figure 1.

The initial NFFCN structure and probability details. Colored dots denote class centroids. Straight segments are decision boundaries induced by the NFFCN split. The mini bar charts sketch the leaf-level class-posterior vector at the reached leaf. No incremental update occurs in this figure. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 1.

The initial NFFCN structure and probability details. Colored dots denote class centroids. Straight segments are decision boundaries induced by the NFFCN split. The mini bar charts sketch the leaf-level class-posterior vector at the reached leaf. No incremental update occurs in this figure. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 2.

NFFCN-ULS structure and probability details. New class samples traverse the fixed trees; only at the reached leaves is updated, while split functions and topology remain unchanged. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 2.

NFFCN-ULS structure and probability details. New class samples traverse the fixed trees; only at the reached leaves is updated, while split functions and topology remain unchanged. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 3.

NFFCN-IGT structure and probability details. When a leaf accumulates sufficient evidence for a novel class, a new local split is learned from the combined data and attached to that leaf. Boundaries change only inside the newly grown subtree, and leaf posteriors are updated there. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 3.

NFFCN-IGT structure and probability details. When a leaf accumulates sufficient evidence for a novel class, a new local split is learned from the combined data and attached to that leaf. Boundaries change only inside the newly grown subtree, and leaf posteriors are updated there. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 4.

NFFCN-RTST structure and probability details. Internal nodes with strong novelty or high uncertainty are selected; their subtrees are pruned and regrown using stored references and new increment data, re-estimating splits and recomputing in the affected regions. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 4.

NFFCN-RTST structure and probability details. Internal nodes with strong novelty or high uncertainty are selected; their subtrees are pruned and regrown using stored references and new increment data, re-estimating splits and recomputing in the affected regions. The mini bar charts use x for the class index and y for the posterior probability , which ranges from 0 to 1.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrices of six classifiers on rRuler dataset. Rows show true classes and columns show predicted classes.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrices of six classifiers on rRuler dataset. Rows show true classes and columns show predicted classes.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrices of six classifiers on Stan WiFi dataset. Rows show true classes, columns show predicted classes; each entry is size of test samples.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrices of six classifiers on Stan WiFi dataset. Rows show true classes, columns show predicted classes; each entry is size of test samples.

Table 1.

Pros and cons of representative studies cited in related work for real-time class-incremental updates.

Table 1.

Pros and cons of representative studies cited in related work for real-time class-incremental updates.

| Reference | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Ye et al. (2024), [19] | Proposes a deep metric ensemble for cross-person HAR with Wi-Fi CSI; emphasizes improved generalization across users. | Not designed for class-incremental updates; adding classes typically requires retraining; update latency and edge compute are not bounded or analyzed. |

| Wei et al. (2024), [18] | Privacy-friendly passive Wi-Fi pipeline; supports class-incremental identity updates and unlearning in dynamic settings. | Focuses on identity rather than multi-activity HAR; real-time latency under resource constraints is not quantified. |

| Pan & Zhu (2025), [20] | Few-shot CIL on radar; aims to mitigate catastrophic forgetting with prompt-driven adaptation using limited samples. | Requires prompt scaffolding and training; no explicit bound on on-device update time or compute; edge real-time suitability not demonstrated. |

| Hashima et al. (2024), [22] | Argues that RIS can enhance robustness under low-SNR via programmable reflections; outlines B5G/6G sensing opportunities. | Depends on specialized RIS hardware and calibration; discussion is forward-looking and does not provide a lightweight class-incremental update path or latency analysis. |

| Rizk & Hashima (2024), [23] | Integrates RIS with a deep learning/feature space pipeline; reports high recognition robustness under noisy CSI. | Pipeline is compute-intensive; no streamlined class-incremental mechanism; on-device update latency and memory footprint are not addressed. |

| Gu et al. (2024), [25] | Proposes a robot-mounted mmWave system with lightweight DNNs targeting real-time monitoring; discusses continuous HAR challenges. | Domain-specific deployment; study itself notes difficulties such as sparse point clouds and continuous classification; does not establish a class-incremental update routine. |

Table 2.

The computational cost of six classifiers on the rRuler dataset.

Table 2.

The computational cost of six classifiers on the rRuler dataset.

| Algorithm | Train Time(s) | Test Time(s) |

|---|

| NFFCN | 2.2480 ± 0.0793 | 0.2413 ± 0.0062 |

| KNN | 1.2590 ± 0.0364 | 0.1968 ± 0.0047 |

| RF | 0.6860 ± 0.0281 | 0.0191 ± 0.0005 |

| SVM | 20.7310 ± 1.4820 | 0.0028 ± 0.0002 |

| GBDT | 57.2130 ± 3.1670 | 0.0032 ± 0.0004 |

| DT | 1.1588 ± 0.0426 | 0.0033 ± 0.0005 |

Table 3.

The computational cost of six classifiers on the Stan WiFi dataset.

Table 3.

The computational cost of six classifiers on the Stan WiFi dataset.

| Algorithm | Train Time(s) | Test Time(s) |

|---|

| NFFCN | 4.8421 ± 0.1835 | 0.0642 ± 0.0031 |

| KNN | 0.0526 ± 0.0039 | 0.1823 ± 0.0049 |

| RF | 1.3827 ± 0.0584 | 0.0138 ± 0.0005 |

| SVM | 0.2954 ± 0.0267 | 0.0039 ± 0.0002 |

| GBDT | 20.5129 ± 1.3274 | 0.0036 ± 0.0003 |

| DT | 0.2861 ± 0.0126 | 0.0011 ± 0.0001 |

Table 4.

The accuracy of six classifiers on the rRuler dataset.

Table 4.

The accuracy of six classifiers on the rRuler dataset.

| Model\Category | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 6 (%) | 7 (%) |

|---|

| NFFCN-RTST | 97.4 ± 0.6 | 92.3 ± 0.8 | 86.9 ± 1.0 | 87.1 ± 1.1 |

| NFFCN-ULS | 95.2 ± 0.7 | 89.6 ± 0.9 | 88.5 ± 0.9 | 84.0 ± 1.2 |

| NFFCN-IGT | 92.1 ± 0.8 | 88.2 ± 1.0 | 84.7 ± 1.1 | 82.3 ± 1.4 |

| SVM-RTST | 92.3 ± 0.9 | 87.6 ± 1.3 | 72.4 ± 2.1 | 73.1 ± 2.3 |

| SVM-ULS | 89.2 ± 1.5 | 71.5 ± 2.8 | 59.1 ± 3.2 | 51.3 ± 3.6 |

| SVM-IGT | 78.1 ± 2.2 | 67.2 ± 2.7 | 64.3 ± 3.1 | 66.0 ± 3.3 |

Table 5.

The accuracy of six classifiers on the Stan WiFi dataset.

Table 5.

The accuracy of six classifiers on the Stan WiFi dataset.

| Model\Category | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 6 (%) | 7 (%) |

|---|

| NFFCN-RTST | 100 ± 0.0 | 99.4 ± 0.4 | 99.5 ± 0.3 | 96.7 ± 0.6 | 95.9 ± 0.7 |

| NFFCN-ULS | 100 ± 0.0 | 82.1 ± 2.8 | 66.3 ± 3.6 | 57.6 ± 4.1 | 50.2 ± 4.5 |

| NFFCN-IGT | 100 ± 0.0 | 99.2 ± 0.5 | 99.4 ± 0.4 | 95.6 ± 0.8 | 95.1 ± 1.0 |

| SVM-RTST | 100 ± 0.0 | 98.6 ± 0.6 | 98.5 ± 0.7 | 98.2 ± 0.6 | 97.5 ± 0.8 |

| SVM-ULS | 100 ± 0.0 | 77.6 ± 3.2 | 61.4 ± 3.8 | 51.8 ± 4.2 | 46.3 ± 4.9 |

| SVM-IGT | 100 ± 0.0 | 98.4 ± 0.7 | 98.7 ± 0.6 | 98.1 ± 0.7 | 97.2 ± 0.9 |

Table 6.

Calculation cost table of six classifiers on rRuler dataset.

Table 6.

Calculation cost table of six classifiers on rRuler dataset.

| Model\Category | 4 (s) | 5 (s) | 6 (s) | 7 (s) |

|---|

| NFFCN-RTST | 1.0830 ± 0.0793 | 0.0982 ± 0.0061 | 1.0368 ± 0.0747 | 1.2514 ± 0.0865 |

| NFFCN-ULS | 0.9123 ± 0.0478 | 0.0882 ± 0.0051 | 0.0821 ± 0.0063 | 0.0784 ± 0.0057 |

| NFFCN-IGT | 0.8772 ± 0.0556 | 0.8115 ± 0.0692 | 0.8731 ± 0.0614 | 1.0486 ± 0.0823 |

| SVM-RTST | 37.4224 ± 2.8530 | 28.3127 ± 2.1410 | 44.0945 ± 3.6241 | 50.7764 ± 1.9412 |

| SVM-ULS | 9.6179 ± 0.7120 | 0.0312 ± 0.0041 | 0.3750 ± 0.0214 | 0.4410 ± 0.0273 |

| SVM-IGT | 20.8751 ± 1.3582 | 28.4423 ± 1.9241 | 43.8161 ± 2.8424 | 49.9357 ± 1.2743 |

Table 7.

Calculation cost table of six classifiers on Stan WiFi dataset.

Table 7.

Calculation cost table of six classifiers on Stan WiFi dataset.

| Model\Category | 3 (s) | 4 (s) | 5 (s) | 6 (s) | 7 (s) |

|---|

| NFFCN-RTST | 1.0580 ± 0.0715 | 1.7624 ± 0.0867 | 2.6912 ± 0.1123 | 3.1786 ± 0.1248 | 3.7224 ± 0.1369 |

| NFFCN-ULS | 0.8421 ± 0.0368 | 0.0623 ± 0.0041 | 0.0437 ± 0.0035 | 0.0569 ± 0.0044 | 0.0486 ± 0.0039 |

| NFFCN-IGT | 0.8026 ± 0.0415 | 1.5328 ± 0.0637 | 1.9147 ± 0.0742 | 3.4389 ± 0.1283 | 3.3421 ± 0.1206 |

| SVM-RTST | 13.1024 ± 0.9921 | 22.9806 ± 1.7035 | 21.2409 ± 1.6164 | 37.5203 ± 2.8542 | 47.8807 ± 2.1968 |

| SVM-ULS | 12.8105 ± 0.7316 | 0.0286 ± 0.0037 | 0.0812 ± 0.0054 | 0.0331 ± 0.0039 | 0.0322 ± 0.0040 |

| SVM-IGT | 12.0148 ± 0.8752 | 21.9807 ± 1.5436 | 20.4205 ± 1.4112 | 36.4709 ± 2.5924 | 52.4803 ± 1.5119 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).