Novel Design and Experimental Validation of a Technique for Suppressing Distortion Originating from Various Sources in Multiantenna Full-Duplex Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- This study developed a method that simultaneously compensates for IQ imbalance, nonlinear PA distortion, and self-interference, thus comprehensively suppressing signal distortion in RF communication.

- (2)

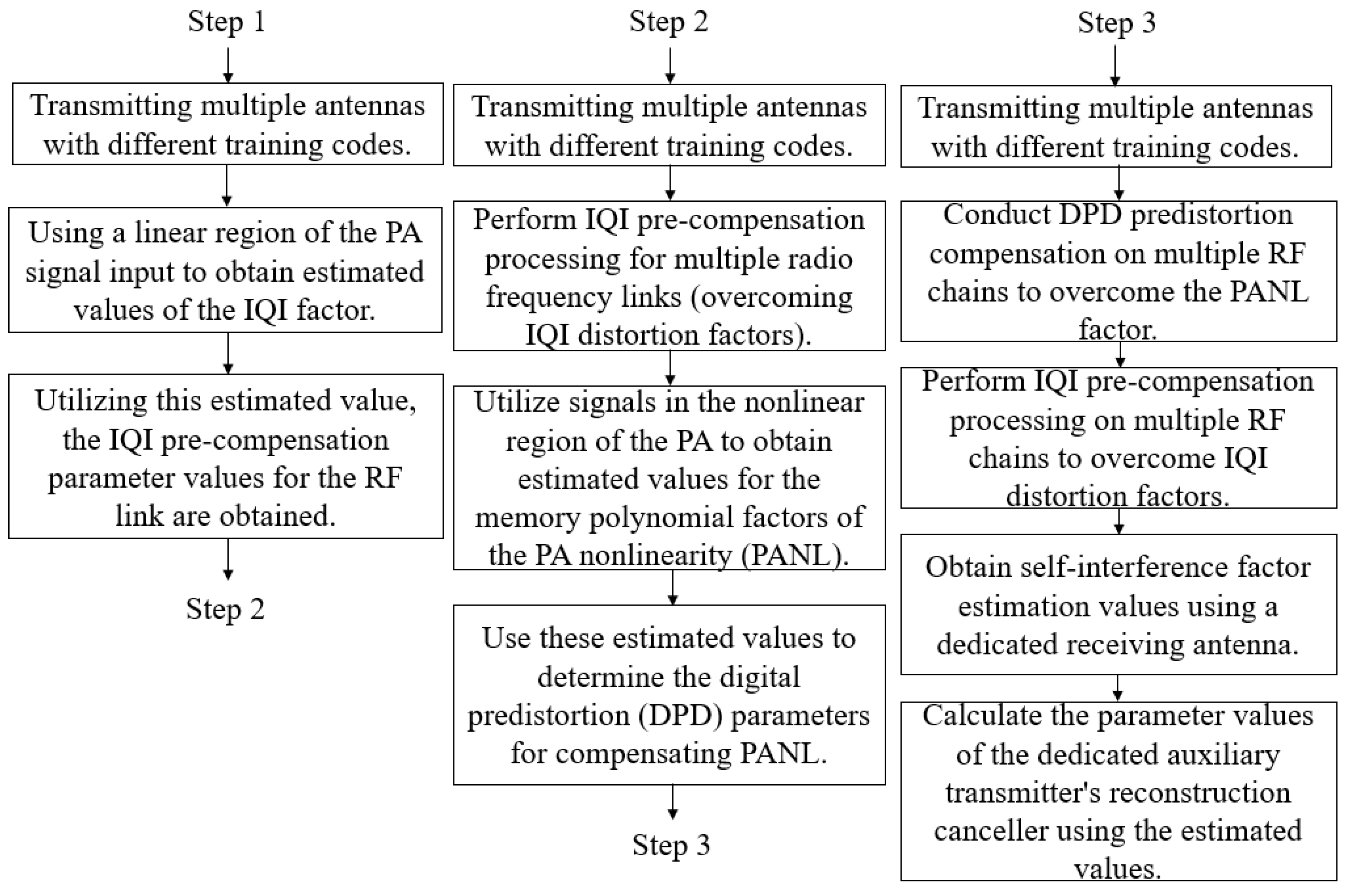

- The developed method involves three steps for achieving progressive distortion suppression.

- (3)

- BL-DPD processing is conducted in the proposed method to reduce the sampling speed required by the DAC and ADC used in the overall system.

- (4)

- This study experimentally validated the proposed method by using a software-defined radio platform, with distortion factor calibration specifically optimized for multiantenna full-duplex transceivers. The experimental results confirm that the proposed method can suppress the three aforementioned types of distortion, highlighting its practical viability in advancing full-duplex communication systems.

2. Proposed RF Distortion Model and Self-Interference in Multiantenna Systems

3. DPD Techniques for Addressing IQ Imbalance, MIMO Self-Interference, and PA Distortion

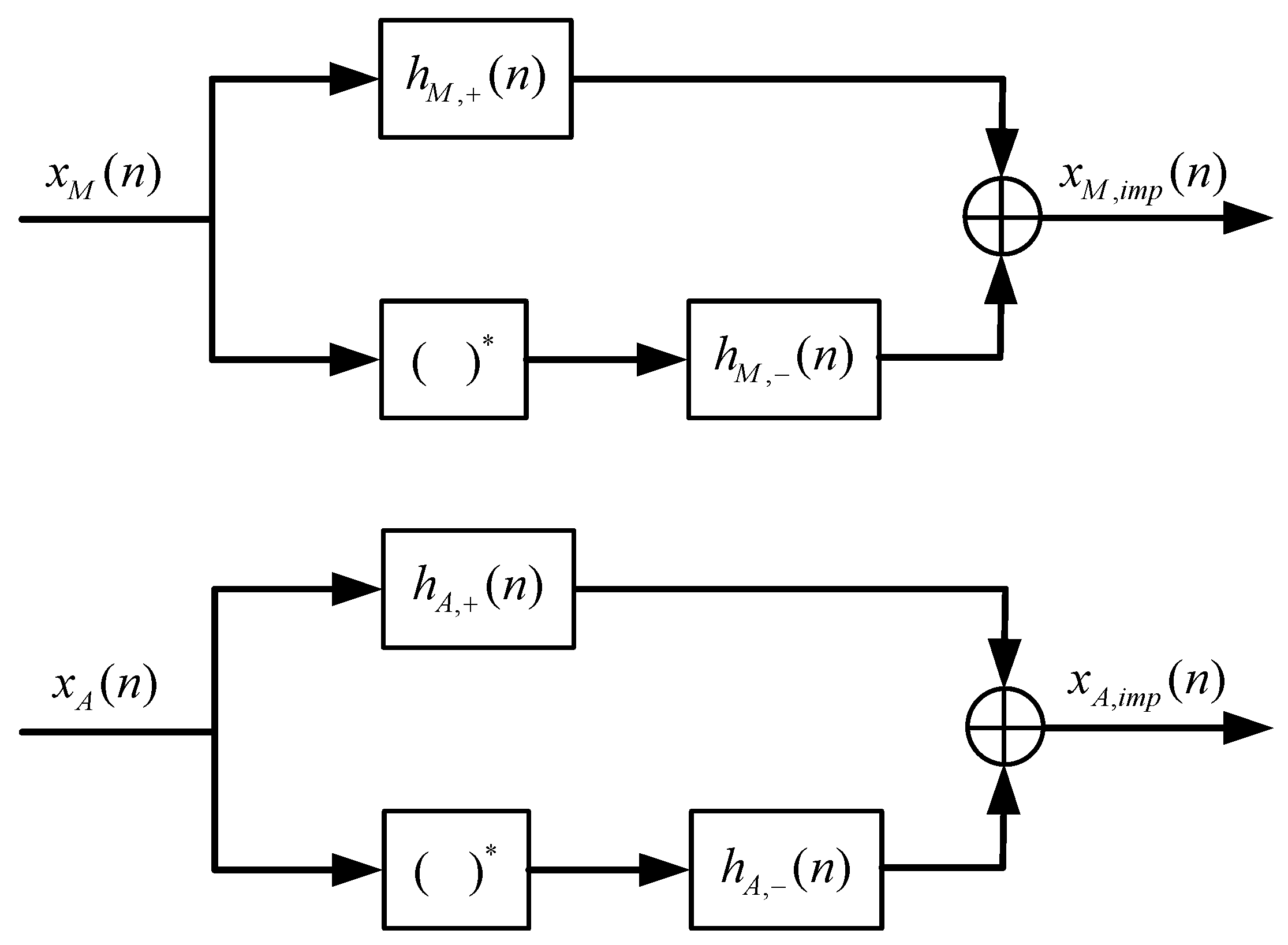

3.1. Compensation for IQ Imbalance

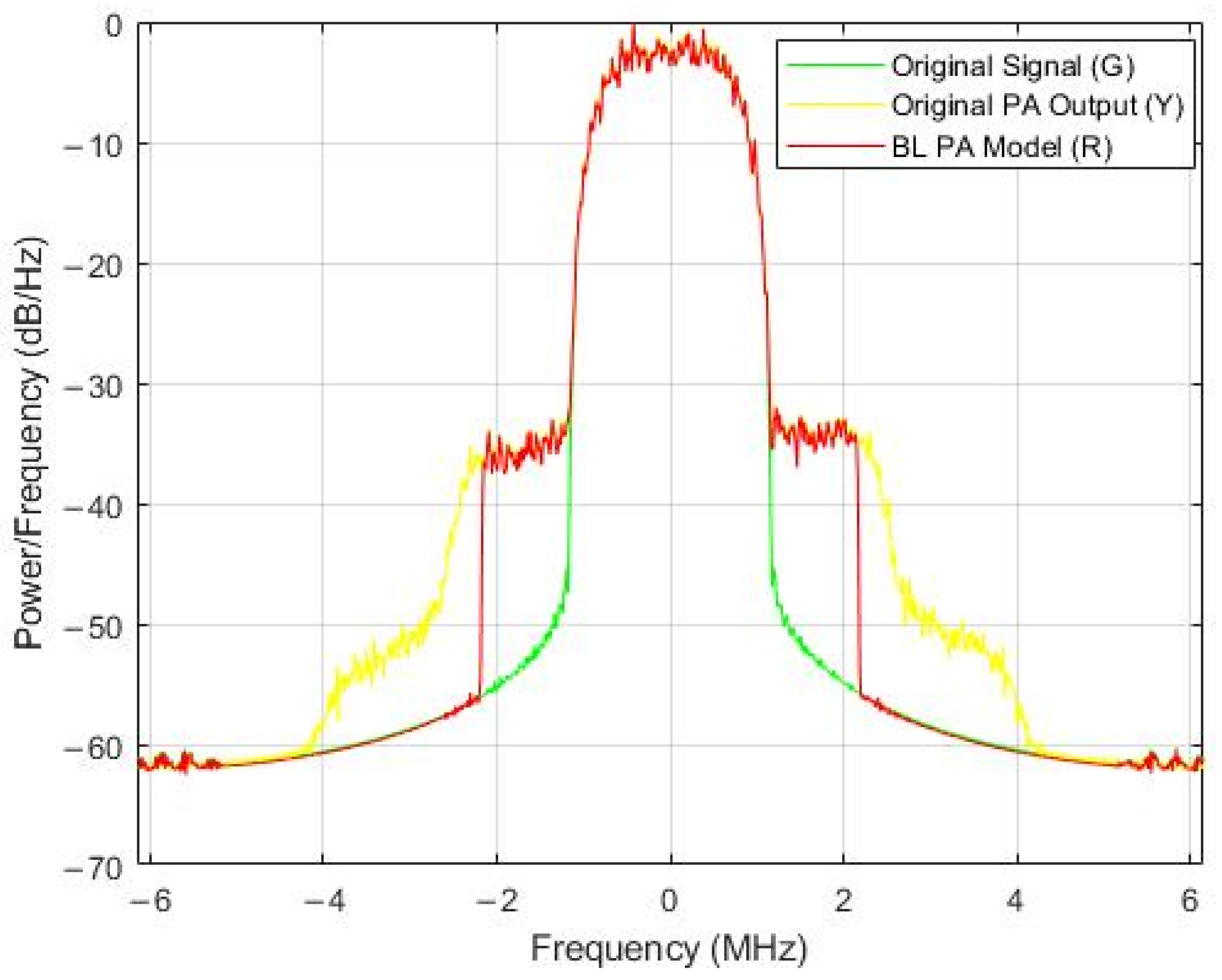

3.2. Compensation for Nonlinear PA Response

3.2.1. Digital Predistortion

3.2.2. Band-Limited DPD

3.3. Active RF Preprocessing Techniques for Addressing Multiantenna Self-Interference

4. Simulation and Experimental Verification of the Proposed Method

4.1. Software Simlation Verification

4.2. Hardware Experimental Verification

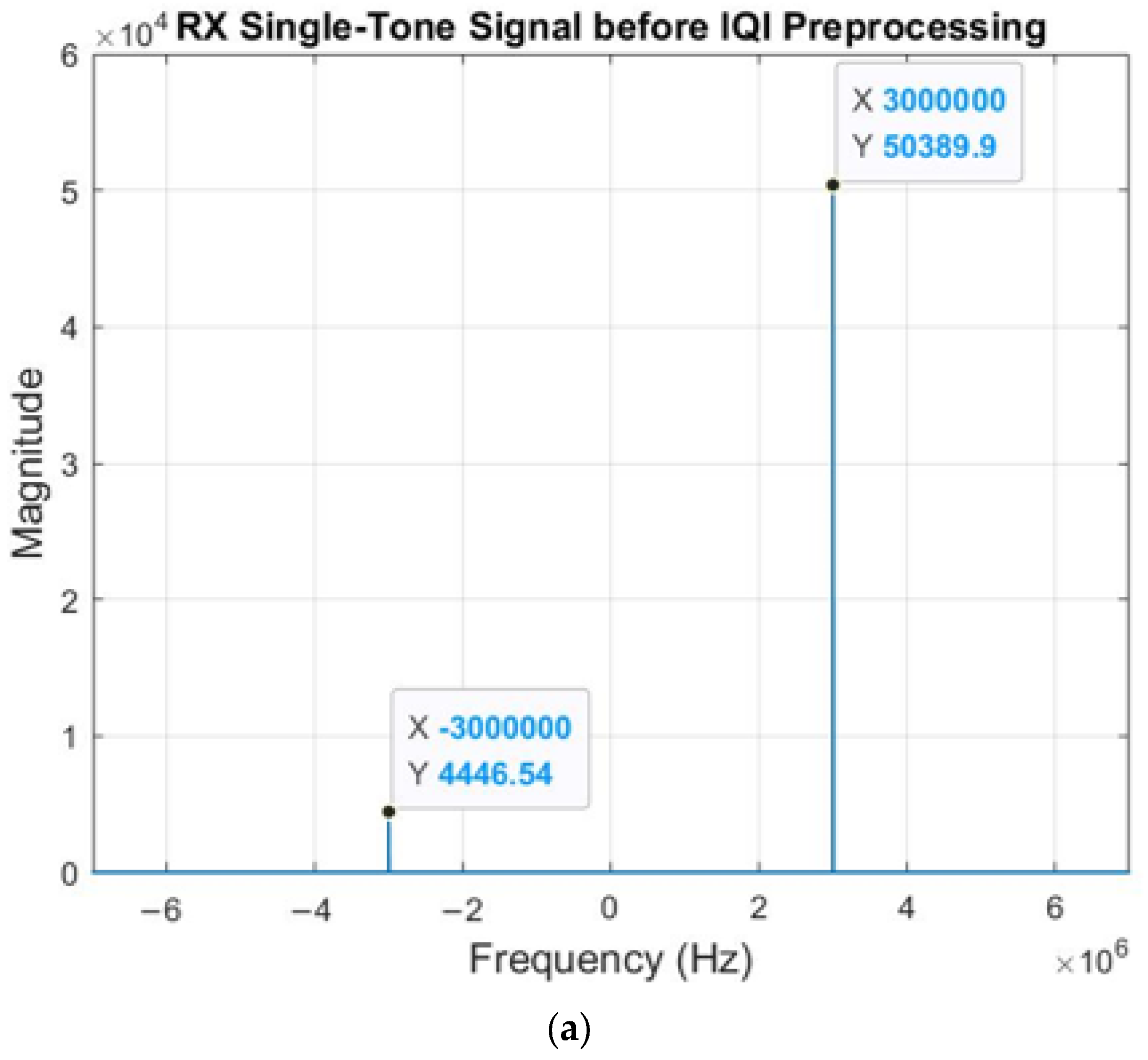

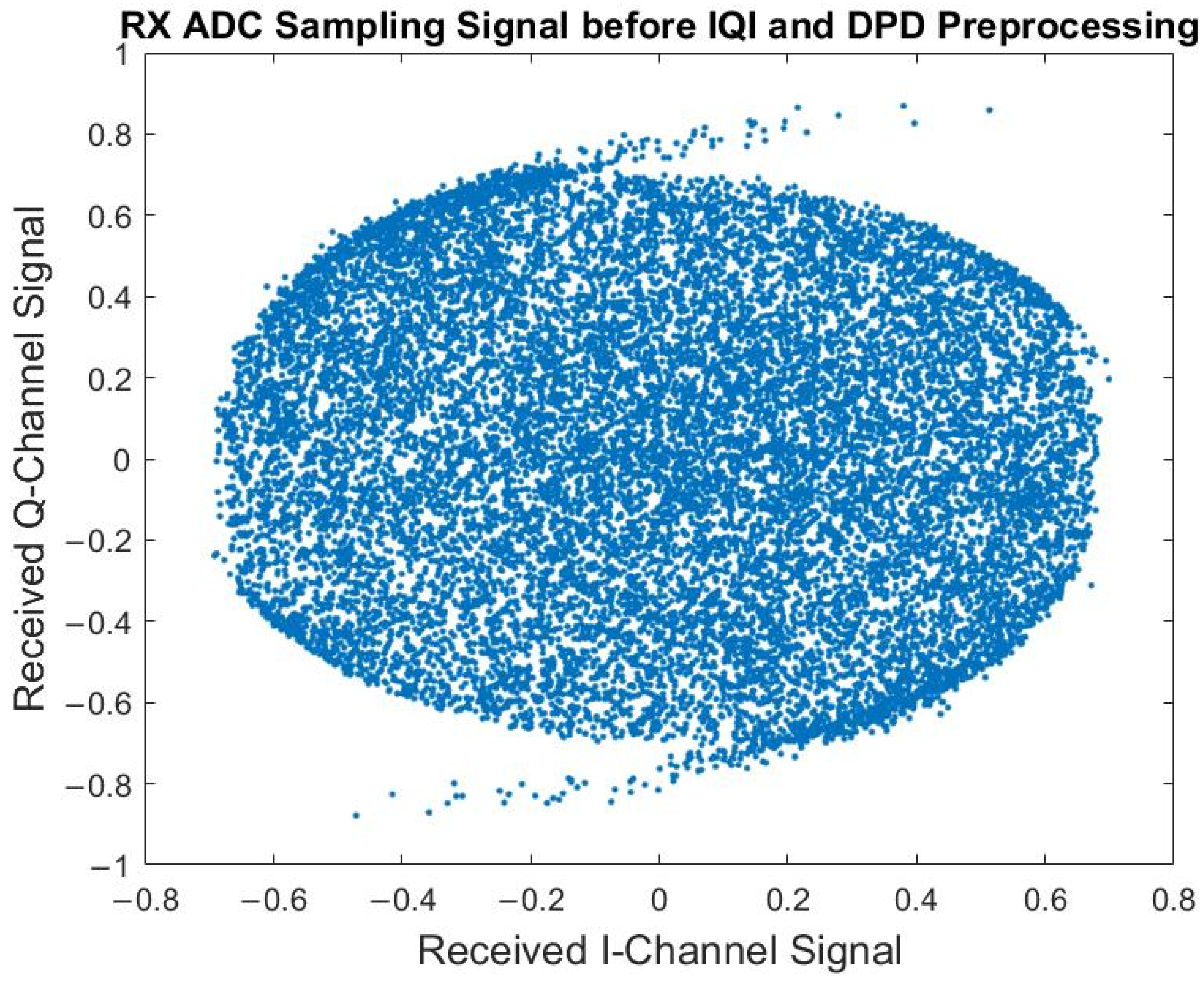

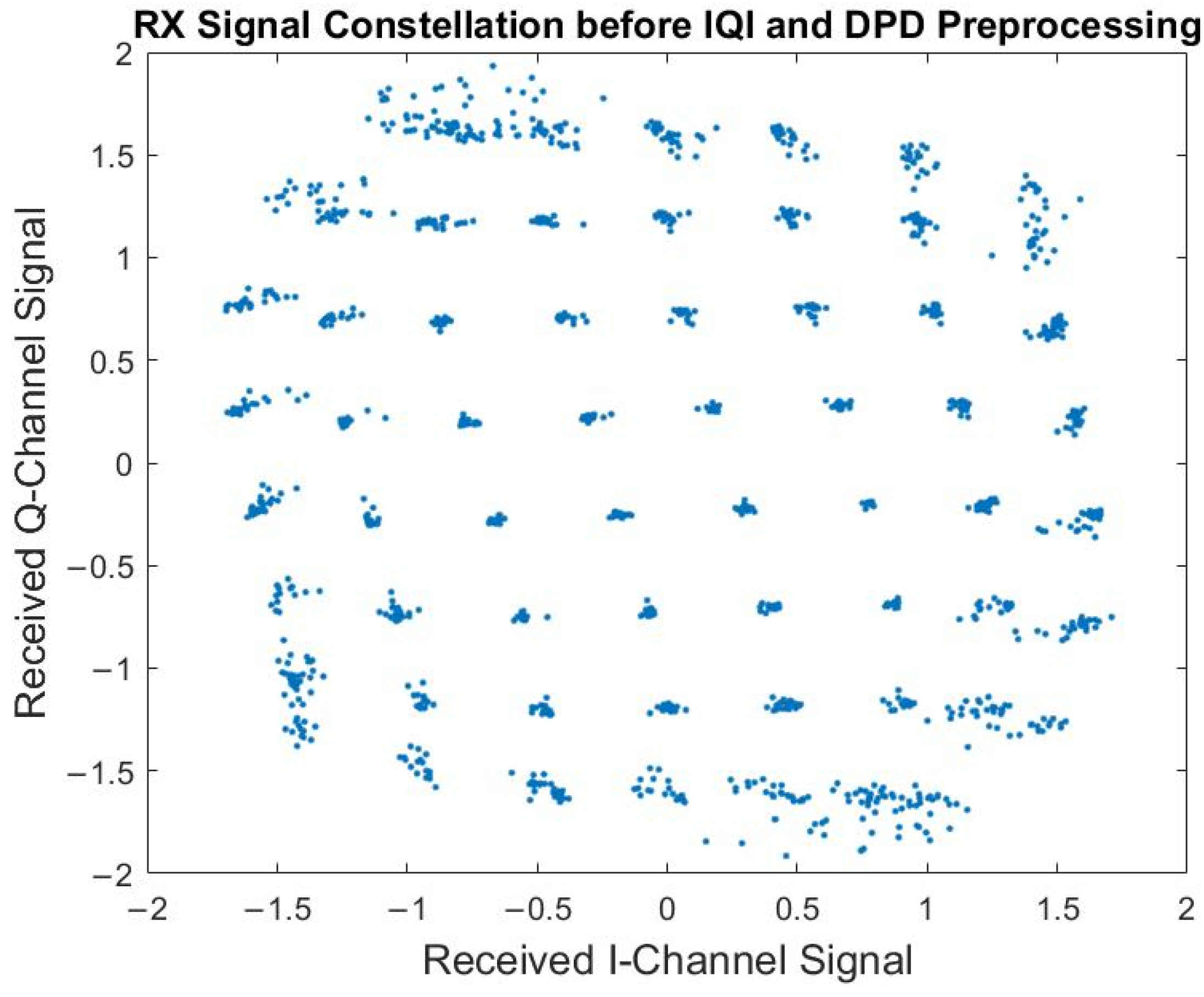

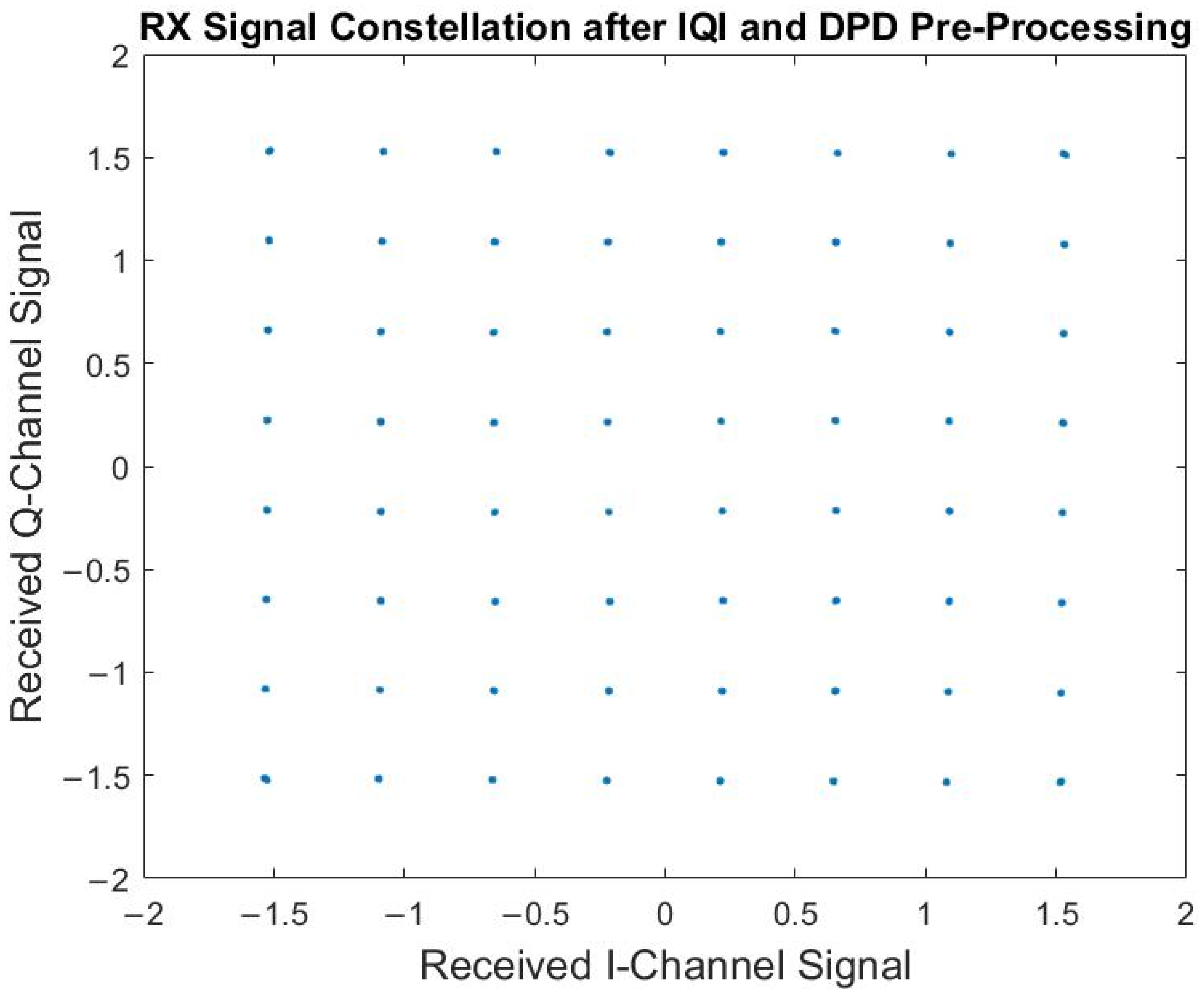

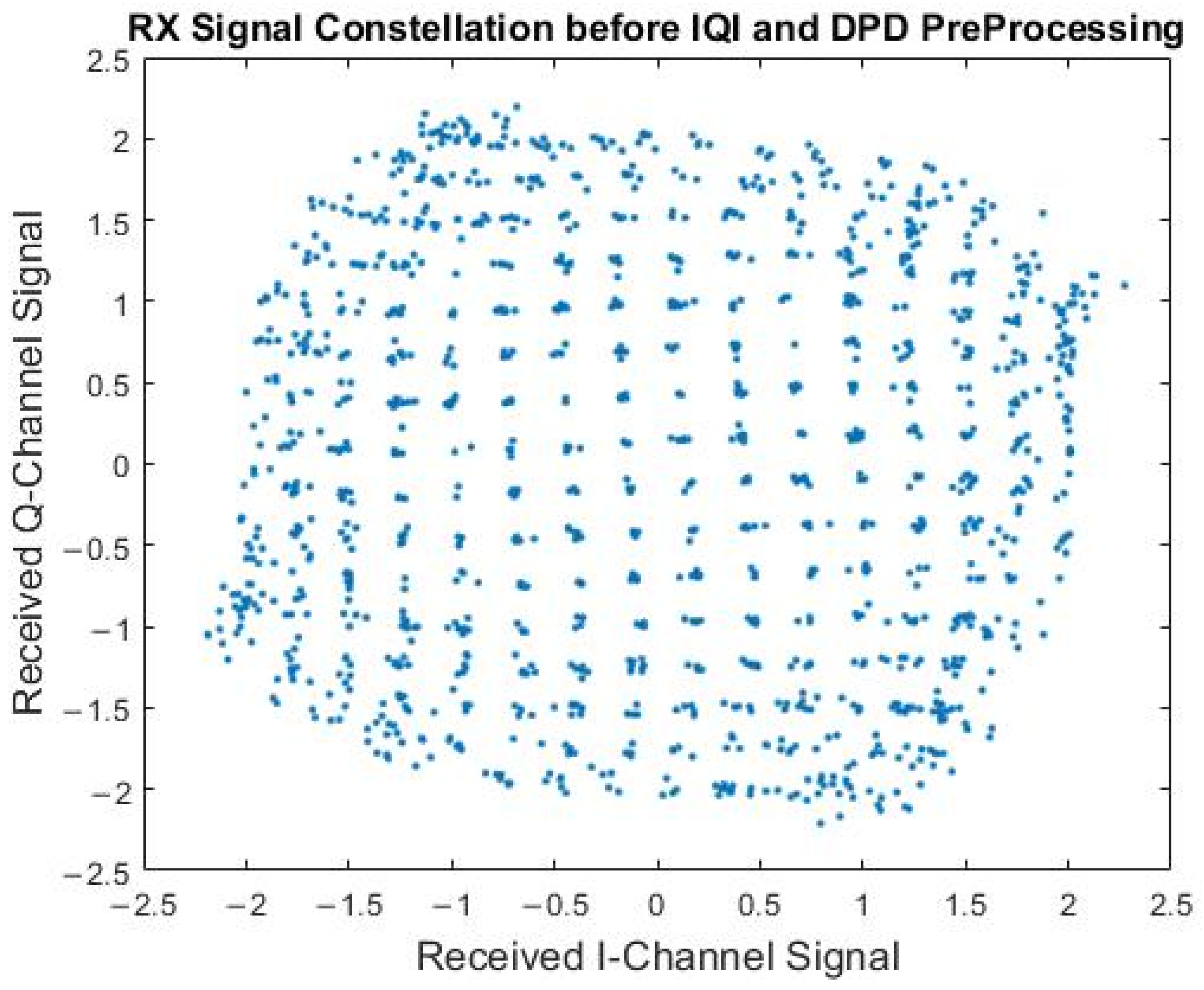

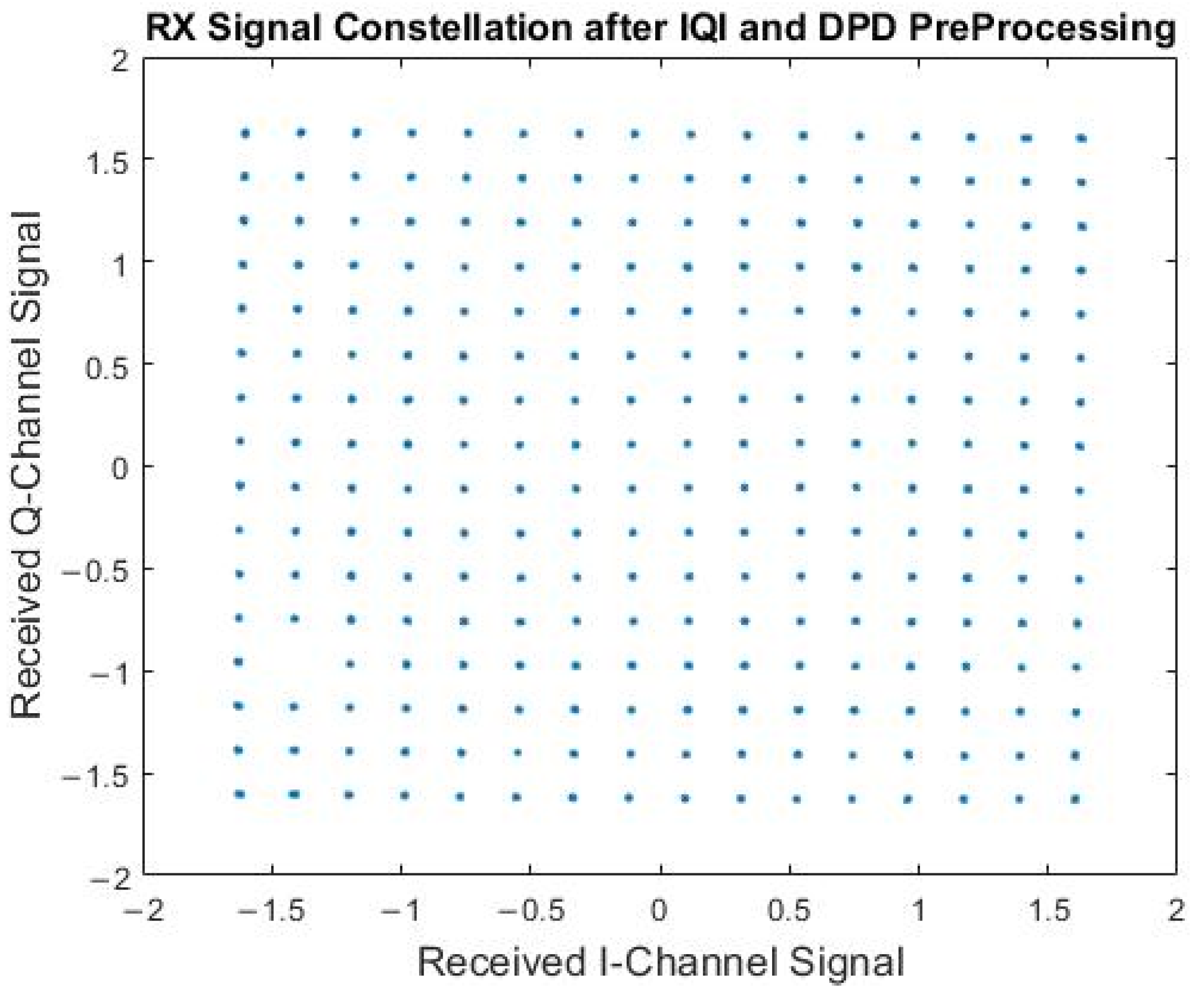

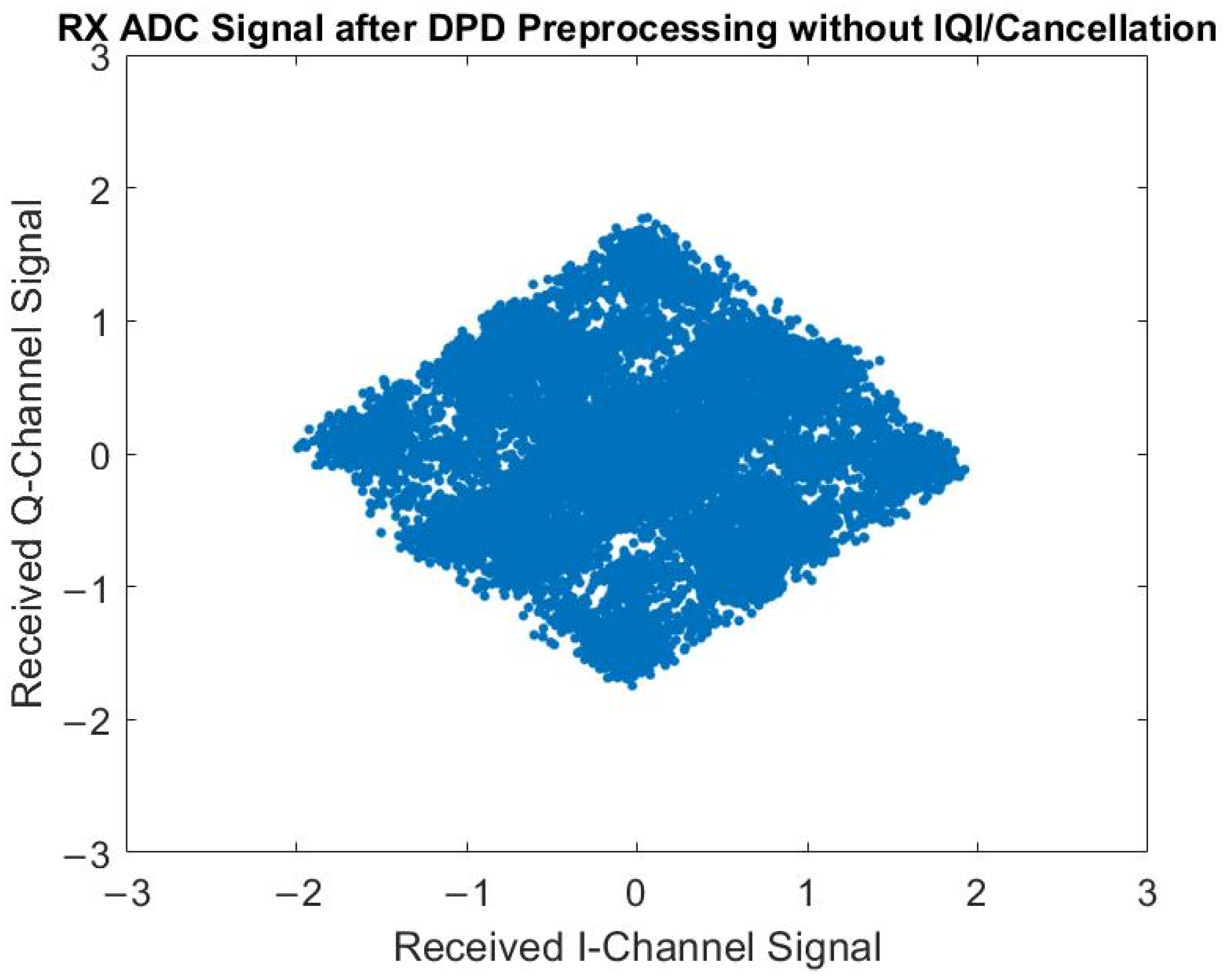

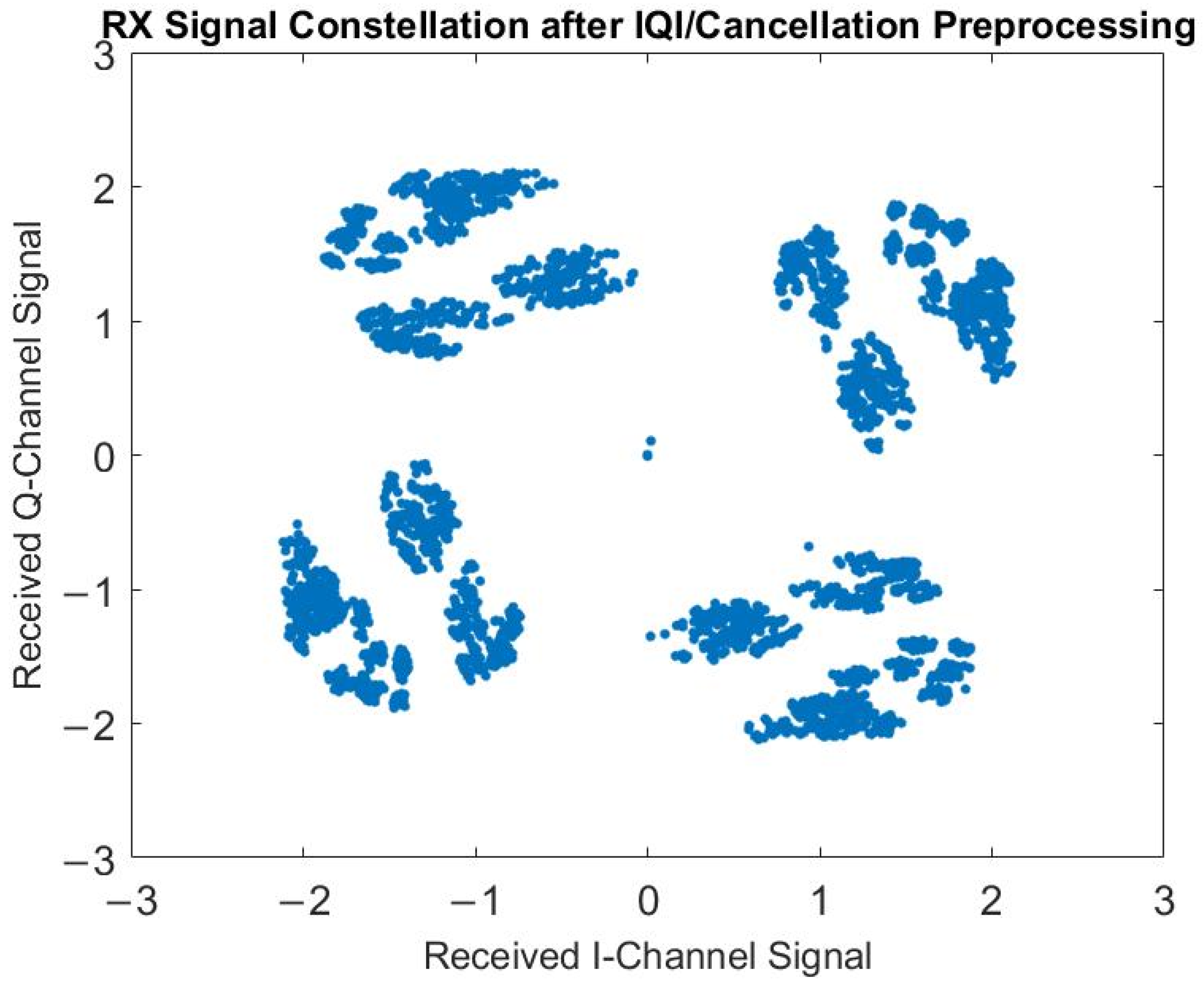

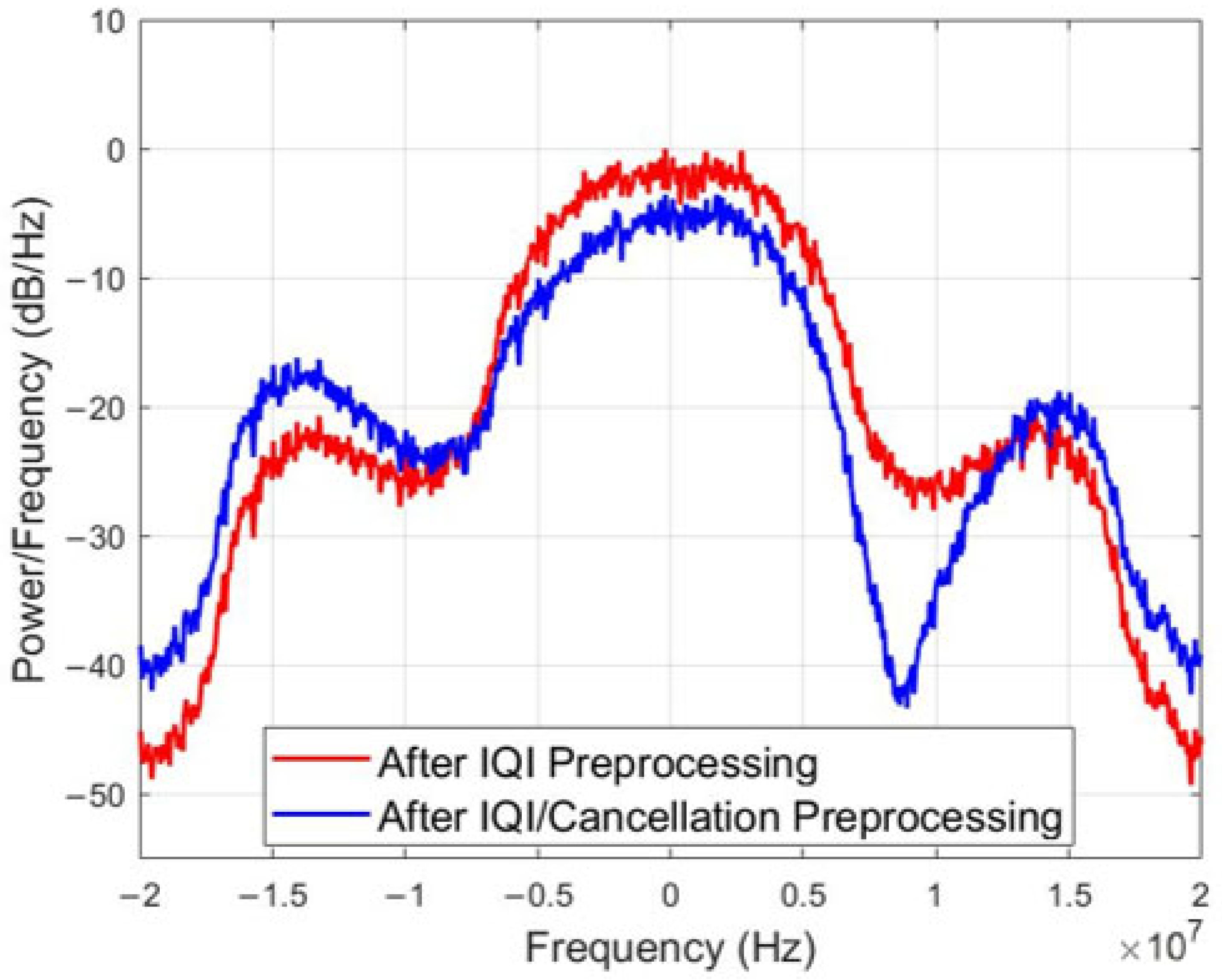

4.2.1. Experimental Verification of the Elimination of RF IQ Imbalance

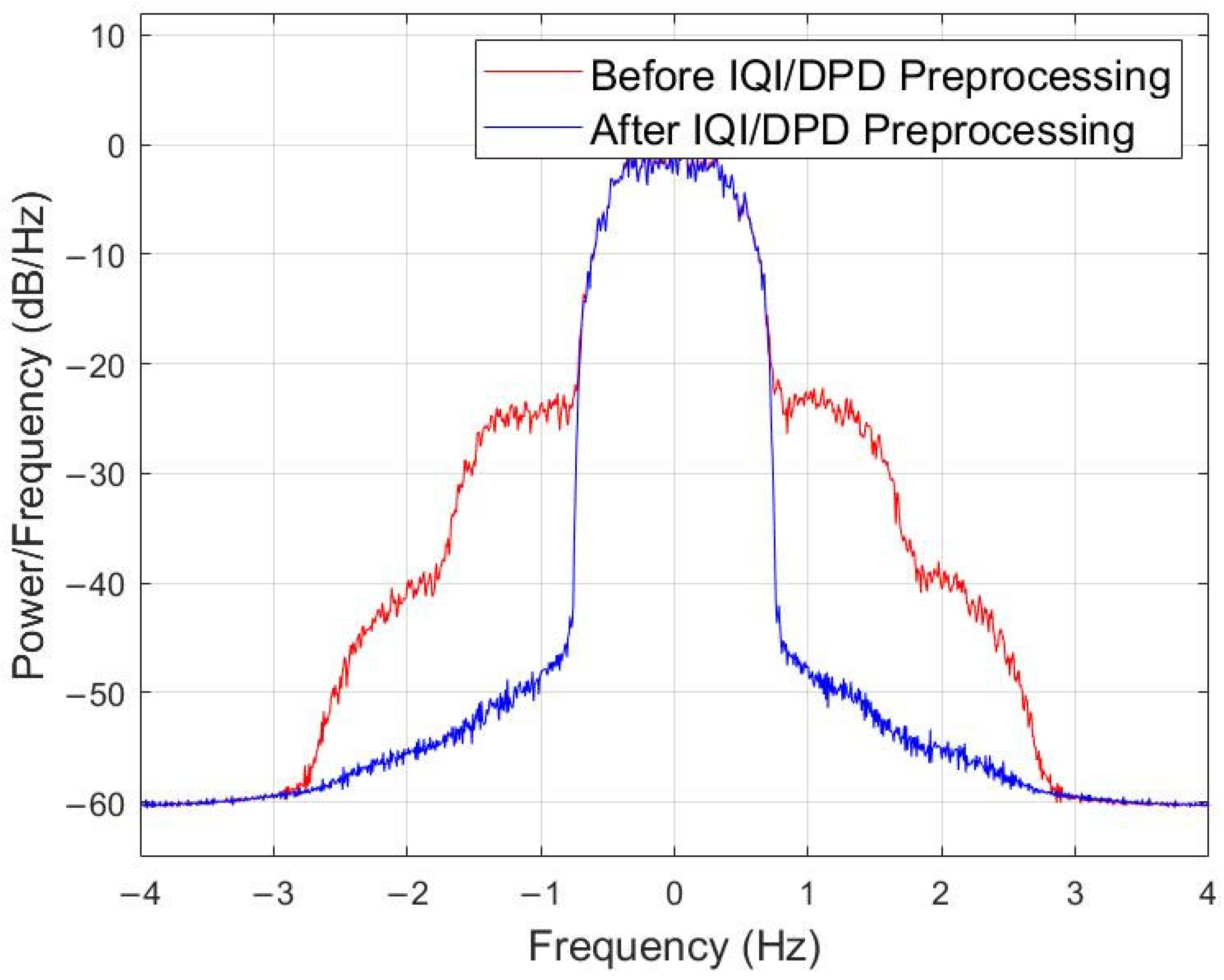

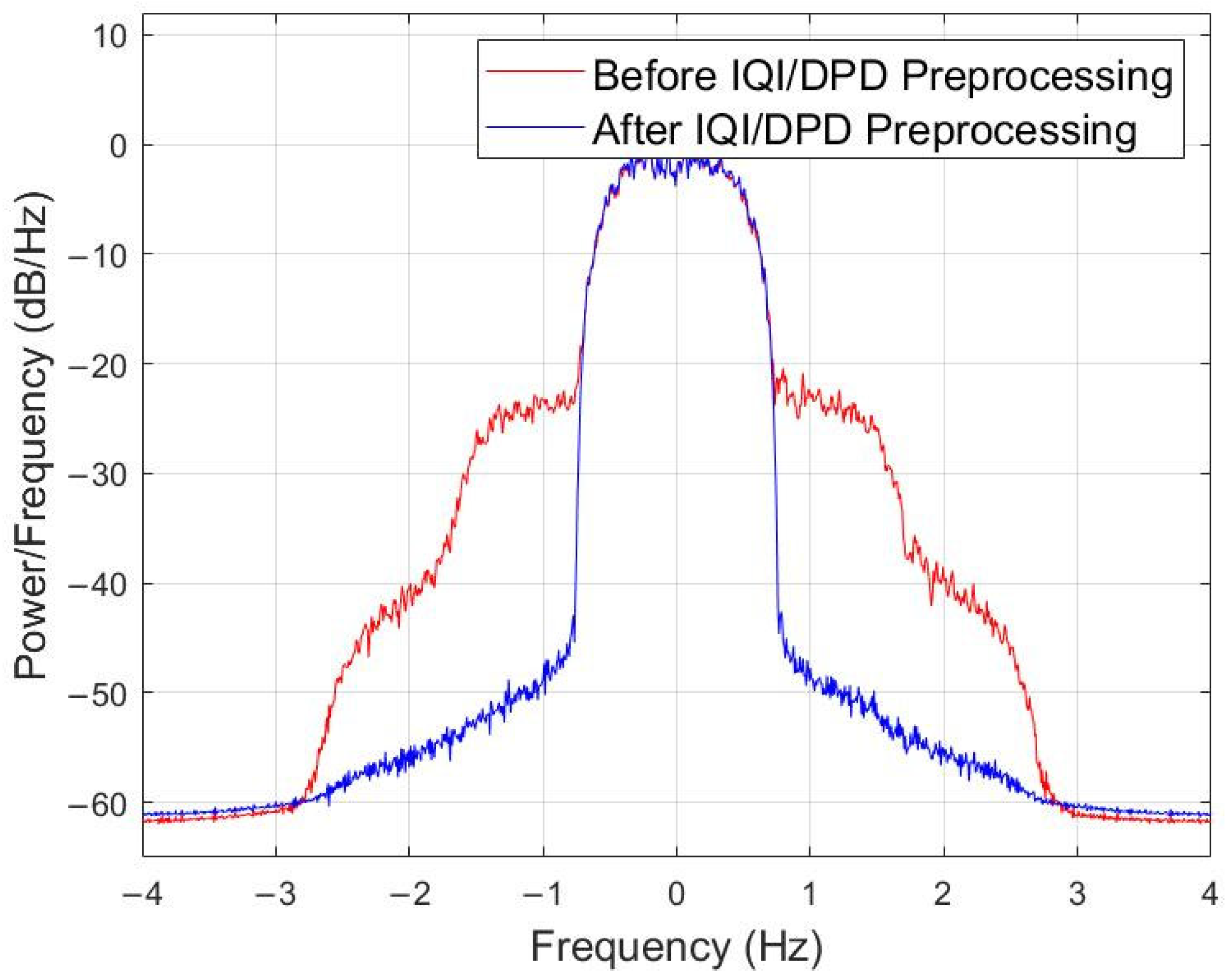

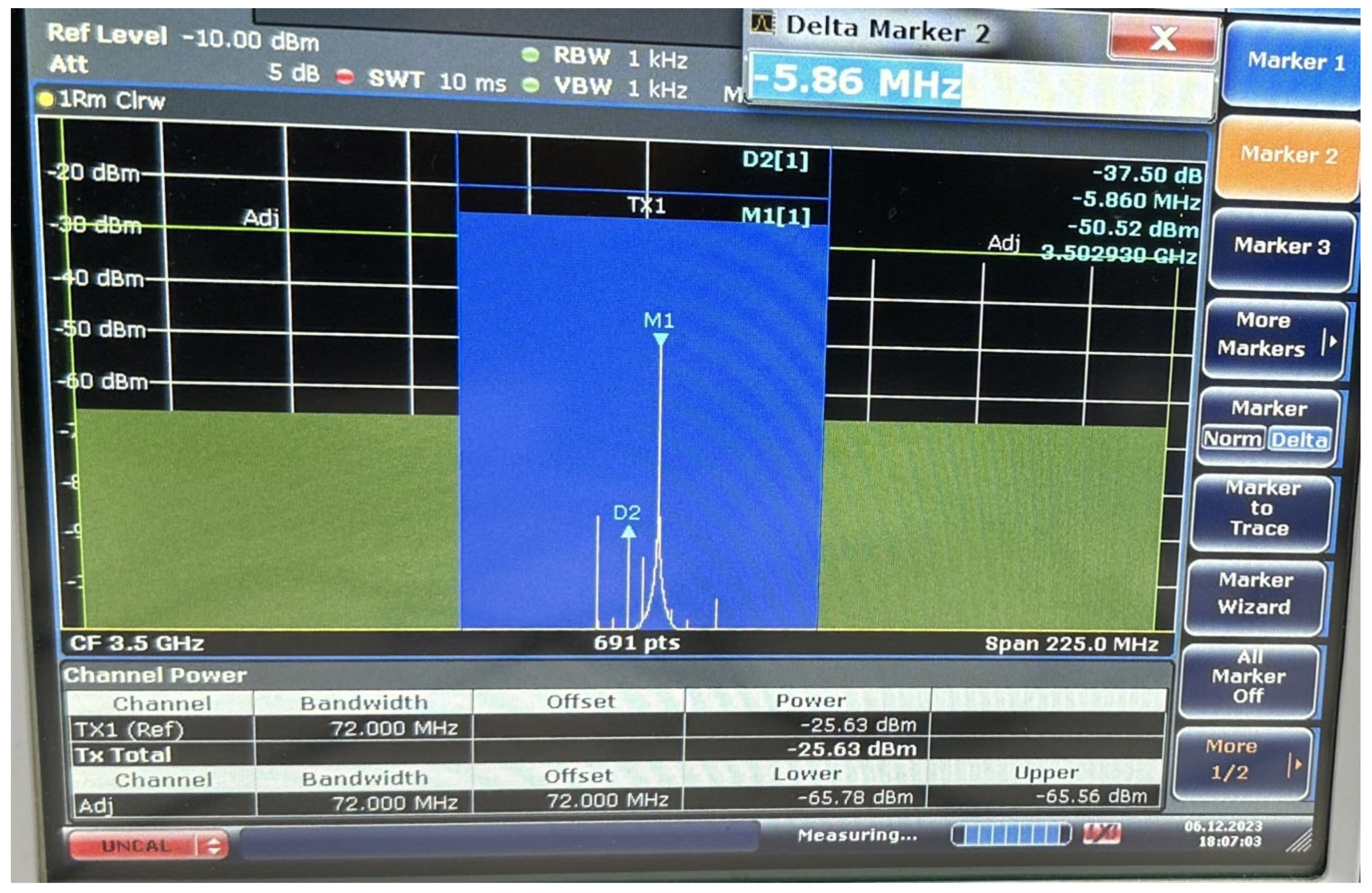

4.2.2. Experimental Validation of the Compensation for Nonlinear PA Response

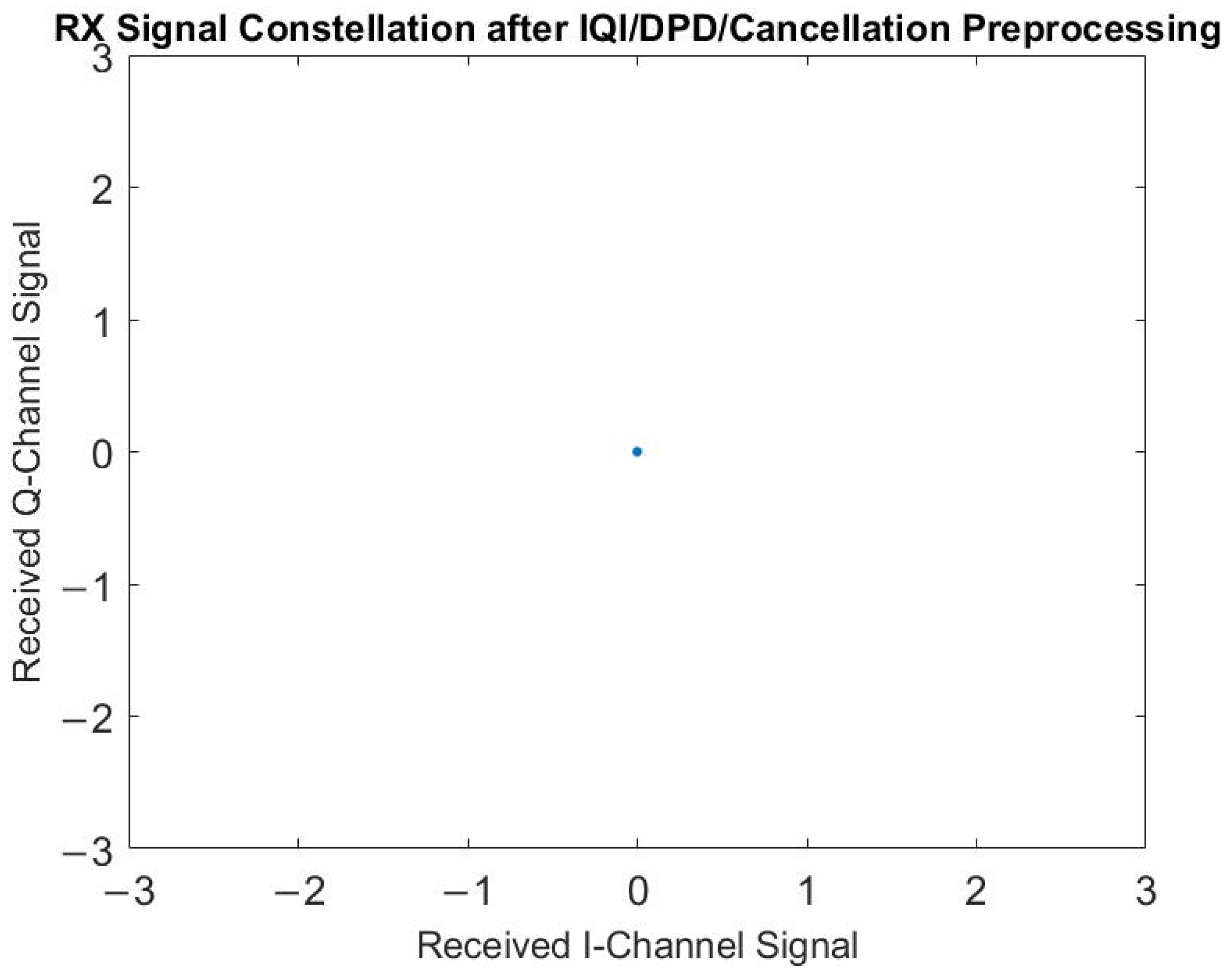

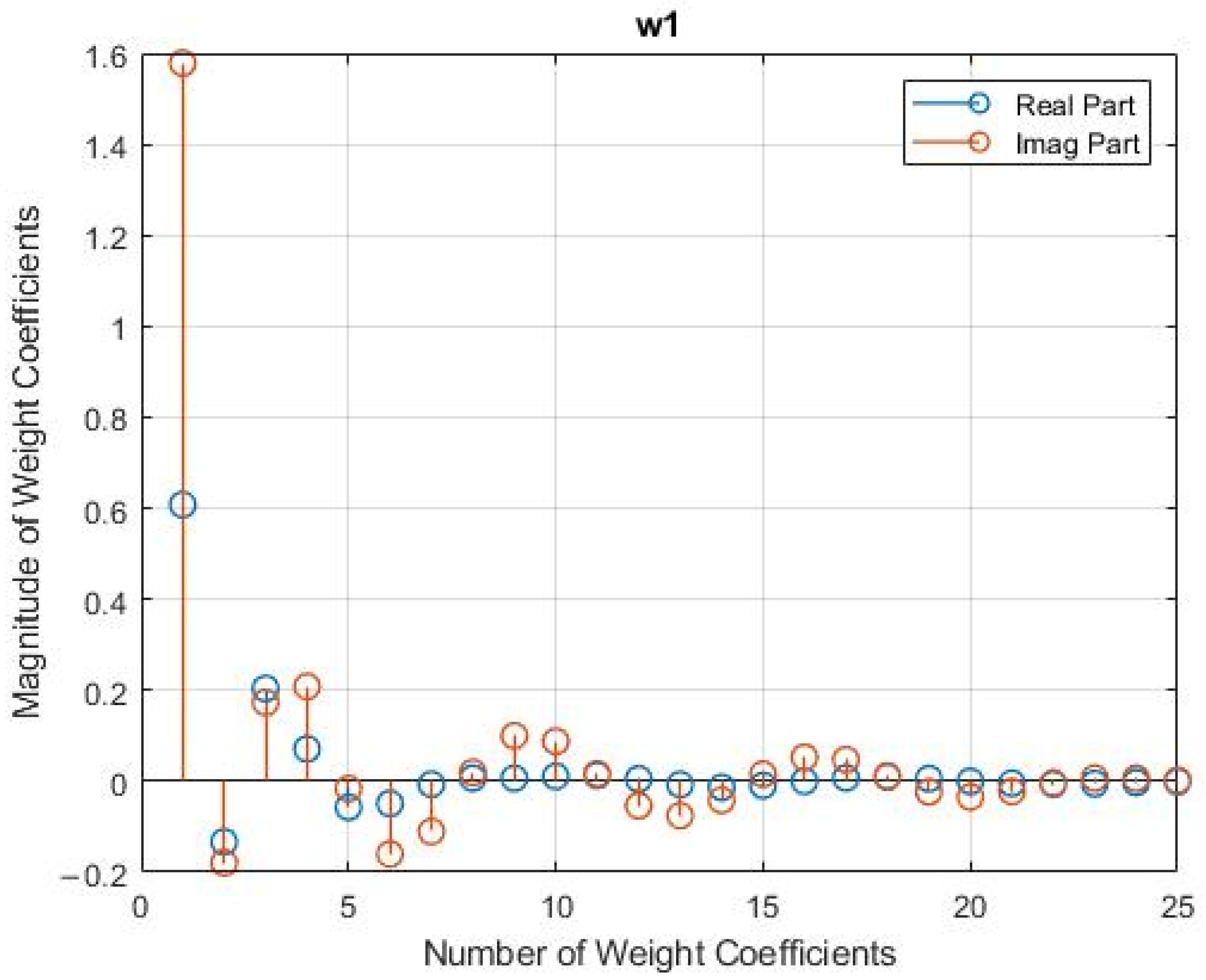

4.2.3. Experimental Verification of the Compensation for MIMO Linear Self-Interference

4.2.4. Verification of the BL-DPD Processing Performance of the Proposed Method Under the Use of Two PAs with Nonlinear Responses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bharadia, D.; McMilin, E.; Katti, S. Full Duplex Radios. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM, Hong Kong, China, 12–16 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, M.; Sabharwal, A. Full Duplex Wireless Communication Using Off-the-Shelf Radios: Feasibility and First Results. In Proceedings of the 2010 Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 7–10 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.I.; Jain, M.; Srinivasan, K.; Levis, P.; Katti, S. Achieving Single Channel, Full Duplex Wireless Communication. In Proceedings of the ACM MOBICOM, Chicago, IL, USA, 20–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, Z.; Xiao, M.; Ding, Z.; Fan, P. Full-Duplex Device-to-Device-Aided Cooperative Nonorthogonal Multiple Access. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 4467–4471. [Google Scholar]

- Kiayani, A.; Abdelaziz, M.; Korpi, D.; Anttila, L.; Valkama, M. Active RF Cancellation with Closed-Loop Adaptation for Improved Isolation in Full-Duplex Radios. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–13 December 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, M.; Lin, H.; Yamashita, K. Adaptive Cancellation of Self-Interference in Full-Duplex Wireless with Transmitter IQ Imbalance. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Globecom Workshops, Austin, TX, USA, 8–12 December 2014; pp. 3220–3224. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, T.; Komatsu, K.; Miyaji, Y.; Uehara, H. Analog Self-Interference Cancellation Using Auxiliary Transmitter Considering IQ Imbalance and Amplifier Nonlinearity. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 7439–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, A.; Tellambura, C. RF Impairments in Wireless Transceivers: Phase noise, CFO, and IQ imbalance—A Survey. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111718–111791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, D.; Anttila, L.; Syrjälä, V.; Valkama, M. Widely Linear Digital Self-Interference Cancellation in Direct-Conversion Full-Duplex Transceiver. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2014, 32, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, K.; Miyaji, Y.; Uehara, H. Iterative Nonlinear Self-Interference Cancellation for In-Band Full-Duplex Wireless Communications Under Mixer Imbalance and Amplifier Nonlinearity. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2020, 19, 4424–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesty, J.; Paleologu, C.; Ciochina, S. Proportionate Adaptive Filters from a Basis Pursuit Perspective. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2010, 17, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Grant, S.L. Proportionate Adaptive Filtering for Block-Sparse System Identification. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2016, 24, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Guan, L.; Zhu, E.; Zhu, A. Band-Limited Volterra Series-Based Digital Predistortion for Wideband RF Power Amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 2012, 60, 4198–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Yu, J.; Li, S. A Modified Band-Limited Digital Predistortion Technique for Broadband Power Amplifiers. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2016, 20, 1800–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumber, K.; Rawat, M. A Modified Hybrid RF Predistorter Linearizer for Ultra Wideband 5G systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst. 2017, 7, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Su, M.; Liu, Y. A Low Sampling Rate Memory Grouped Method for Digital Predistortion with Constrained Acquisition Bandwidth. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 2022, 70, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Shipra; Rawat, M. Bandlimited DPD Adapted APD for 5G Communication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, L.; Lampu, V.; Hassani, S.A.; Campo, P.P.; Korpi, D.; Turunen, M.; Pollin, S.; Valkama, M. Full-duplexing with SDR devices: Algorithms, FPGA implementation, and real-time results. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 20, 2205–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, A.; Majumder, A.; Debbarma, B.; Bhattacharyya, B.K. An Approach of ISI Elimination and High-Speed Data Reconstruction in Lossy On-Chip Serial Link. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, L.R.; Pillai, S.S. A low complexity CFO reduction technique for LFDMA systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information, Communication and Computing Technology, New Delhi, India, 16 July 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Zhou, G.T.; Morgan, D.R.; Ma, Z.; Kenney, J.S.; Kim, J.; Giardina, C.R. A Robust Digital Baseband Predistorter Constructed Using Memory Polynomials. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2004, 52, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.H.; Liu, K.H.; Xiao, Y.Z.; Pan, W.Y.; Ku, M.L.; Lim, S.Y. Spatial Nulling and MIMO Pre-Processing Design for Dual mmWave Active Array SDR Platform with OTA Effects. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 159582–159596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyen, L.A.; Huang, X.; Guo, Y.J. Beam-based Analog Self-interference Cancellation Infull-Duplex MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 2460–2471. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Irigaray, F.J.; Fernandez-Prat, J.S.; Lopez-Martinez, F.J.; Martos-Naya, E.; Cobos-Morales, O.; Entrambasaguas, J.T. Adaptive Self-Interference Cancellation for Full Duplex Radio: Analytical Model and Experimental Validation. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 65018–65026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.H.; Lee, C.F.; Ku, M.L.; Hwang, J.K. Self-Calibration of Joint RF Impairments in a Loopback Wideband Transceiver. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45607–45617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proposed | [8] | [9,10] | [11] | [13] | [14] | [17] | [18] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ imbalance | V | V | V | |||||

| DPD | V | V | V | V | ||||

| Linear filter parameters for the auxiliary path | V | V | V | |||||

| BL-DPD | V | V | ||||||

| Cancellation parameter in TX | V | |||||||

| Cancellation parameter in RX | V |

| Simulation Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Oversampling factor | 4 |

| Symbol rate (fs) | 10 MHz |

| Bandwidth | 5.8 MHz |

| Phase imbalance | 10π/180 degree |

| Amplitude imbalance | 0.2 dB |

| Simulation Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Oversampling factor | 4 |

| Symbol rate (fs) | 10 MHz |

| Bandwidth | 5.8 MHz |

| Memory order | 3 |

| Polynomial order | 5 |

| Phase imbalance | 10π/180 degree |

| Amplitude imbalance | 0.2 dB |

| Parameter | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Operating frequency | 3.4–3.8 GHz |

| Supply voltage | 5.5 V |

| Enable voltage | 2 V |

| Maximum gain | 35 dB |

| Operating temperature | −40 to 100 °C |

| Junction temperature | Up to 155 °C |

| Power consumption | 2.2 W |

| Attenuator | 30 dB |

| Simulation Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Frequency | 3.5 GHz |

| Sampling rate (fs) | 122.88 MHz |

| Oversampling factor | 8 |

| Roll-off | 0.5° |

| Bandwidth | 11.25 MHz |

| Type of input signal | Single tone |

| Phase imbalance | 2° |

| Amplitude imbalance | 2 dB |

| Simulation Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Frequency | 3.5 GHz |

| Signal | 16-QAM |

| Oversampling factor | 16 |

| Roll-off | 0.5 |

| Bandwidth | 5.8 MHz |

| DPD model | MP model |

| DPD learning | ILA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, K.-H.; Deng, J.-H.; Yang, M.-S. Novel Design and Experimental Validation of a Technique for Suppressing Distortion Originating from Various Sources in Multiantenna Full-Duplex Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214300

Liu K-H, Deng J-H, Yang M-S. Novel Design and Experimental Validation of a Technique for Suppressing Distortion Originating from Various Sources in Multiantenna Full-Duplex Systems. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214300

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Keng-Hwa, Juinn-Horng Deng, and Min-Siou Yang. 2025. "Novel Design and Experimental Validation of a Technique for Suppressing Distortion Originating from Various Sources in Multiantenna Full-Duplex Systems" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214300

APA StyleLiu, K.-H., Deng, J.-H., & Yang, M.-S. (2025). Novel Design and Experimental Validation of a Technique for Suppressing Distortion Originating from Various Sources in Multiantenna Full-Duplex Systems. Electronics, 14(21), 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214300