Lightweight Attention-Based Architecture for Accurate Melanoma Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. HU-Net to Pocket-Net to APNet

3.2. Datasets

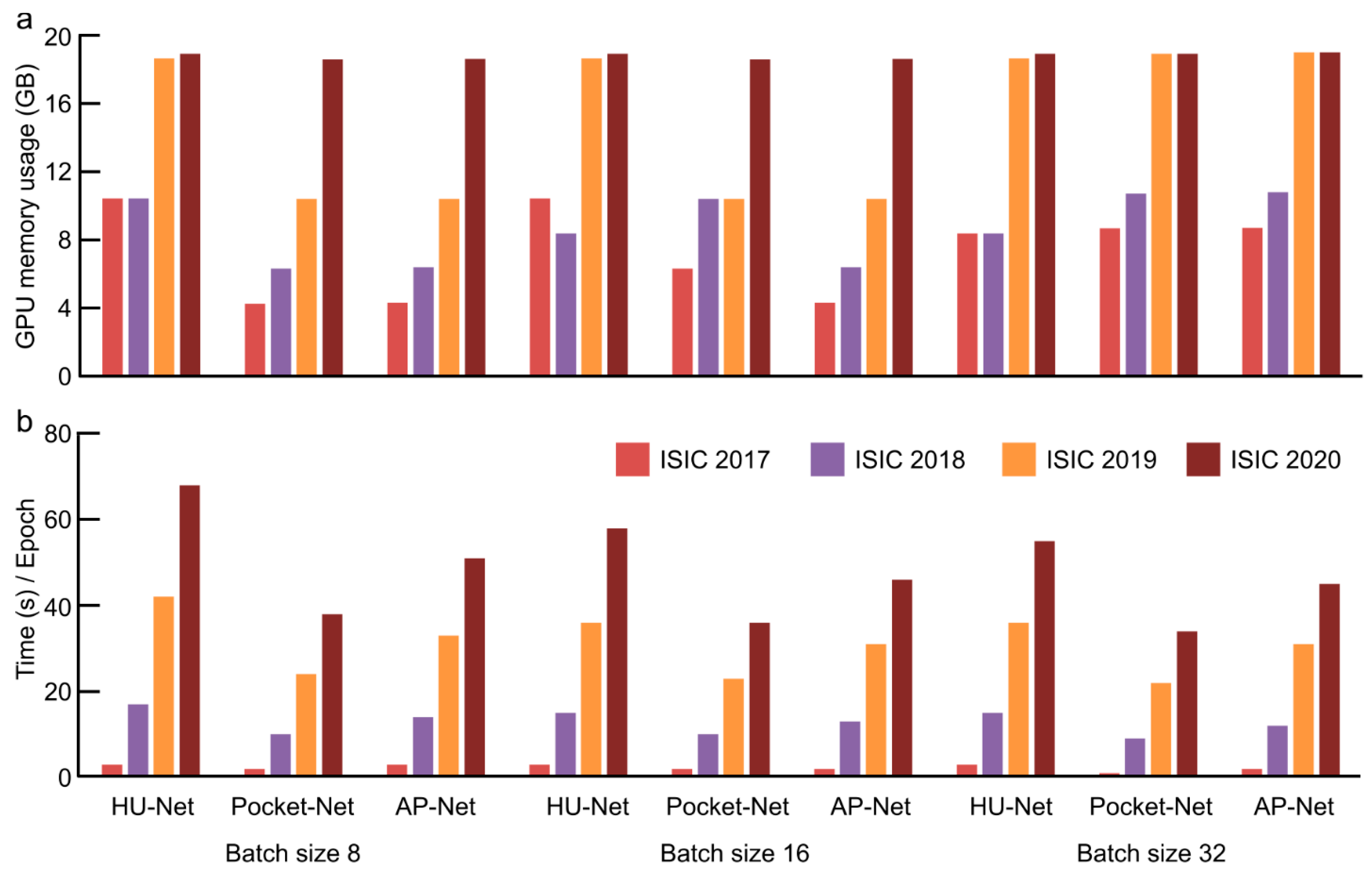

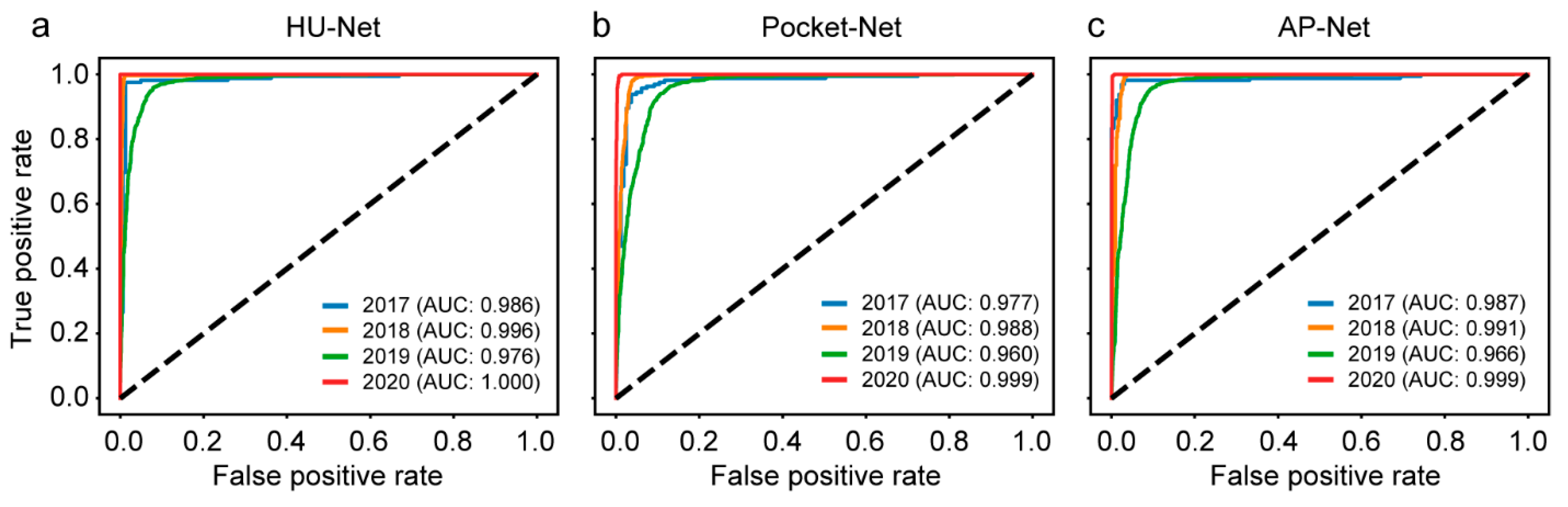

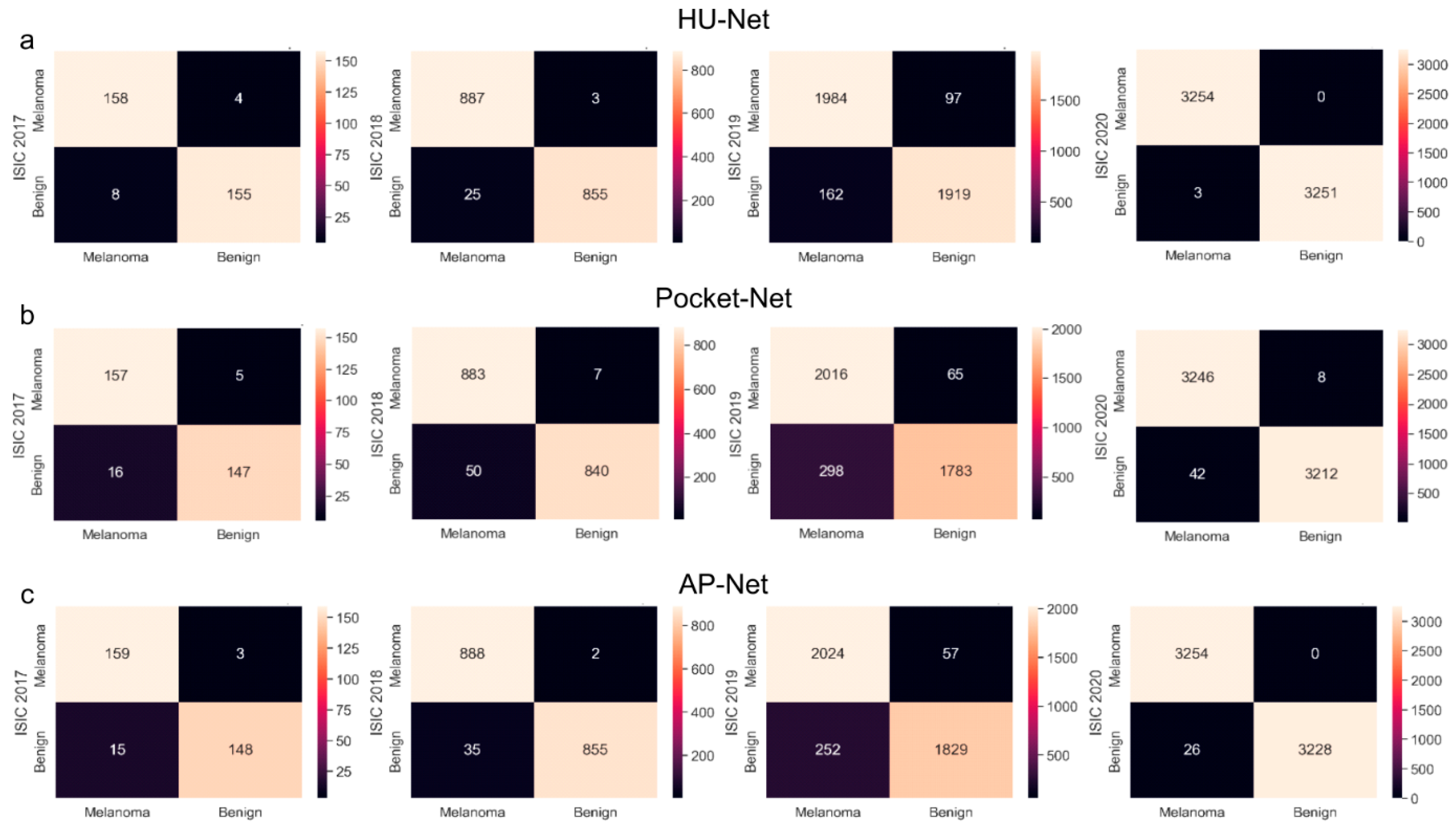

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, H.W.; Weinstock, M.A.; Feldman, S.R.; Coldiron, B.M. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA—Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q. The Advanced Applications for Optical Coherence Tomography in Skin Imaging. Ph.D. Thesis, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eathara, A.; Siegel, A.P.; Tsoukas, M.M.; Avanaki, K. Applications of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in Preclinical Practice. In Bioimaging Modalities in Bioengineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Lara, J.; Siegel, A.P.; Tsoukas, M.M.; Avanaki, K. High-frequency photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging for skin evaluation: Pilot study for the assessment of a chemical burn. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202300460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanaki, M.R.; Hojjat, A.; Podoleanu, A.G. Investigation of computer-based skin cancer detection using optical coherence tomography. J. Mod. Opt. 2009, 56, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’leary, S.; Fotouhi, A.; Turk, D.; Sriranga, P.; Rajabi-Estarabadi, A.; Nouri, K.; Daveluy, S.; Mehregan, D.; Nasiriavanaki, M. OCT image atlas of healthy skin on sun-exposed areas. Ski. Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabi, S.; Turani, Z.; Fatemizadeh, E.; Clayton, A.; Nasiriavanaki, M. Optical coherence tomography technology and quality improvement methods for optical coherence tomography images of skin: A short review. Biomed. Eng. Comput. Biol. 2017, 8, 1179597217713475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabi, S.; Fotouhi, A.; Xu, Q.; Daveluy, S.; Mehregan, D.; Podoleanu, A.; Nasiriavanaki, M. An overview of methods to mitigate artifacts in optical coherence tomography imaging of the skin. Ski. Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, L.; Fakhoury, J.W.; Manwar, R.; Rajabi-Estarabadi, A.; Turk, D.; O’Leary, S.; Fotouhi, A.; Daveluy, S.; Jain, M.; Nouri, K. Review of Non-Invasive Imaging Technologies for Cutaneous Melanoma. Biosensors 2025, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akella, S.S.; Lee, J.; May, J.R.; Puyana, C.; Kravets, S.; Dimitropolous, V.; Tsoukas, M.; Manwar, R.; Avanaki, K. Using optical coherence tomography to optimize Mohs micrographic surgery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachon, J.; Beaulieu, P.; Sei, J.F.; Gouvernet, J.; Claudel, J.P.; Lemaitre, M.; Richard, M.A.; Grob, J.J. First prospective study of the recognition process of melanoma in dermatological practice. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: 4th International Workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Fathan, M.I.; Patel, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, C.; Bansal, A.; Rastogi, A.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, G. Colonoscopy polyp detection and classification: Dataset creation and comparative evaluations. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanoon, M.A.; Zulkifley, M.A.; Mohd Zainuri, M.A.A.; Abdani, S.R. A Review of Deep Learning Techniques for Lung Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Based on CT Images. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, A.K.; Govindarajan, Y.; Prathiba, S.B.; Vinod, A.A.; Ganesan, V.P.A.; Zhu, Z.; Gadekallu, T.R. Federated Learning and Digital Twin-Enabled Distributed Intelligence Framework for 6G Autonomous Transport Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 18214–18224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Zhou, T.; Leung, M.-F. Learning from AI-generated annotations for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; El-Sharkawy, M. Thin MobileNet: An Enhanced MobileNet Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 10–12 October 2019; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Celaya, A.; Actor, J.A.; Muthusivarajan, R.; Gates, E.; Chung, C.; Schellingerhout, D.; Riviere, B.; Fuentes, D. Pocketnet: A smaller neural network for medical image analysis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 42, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Um, K.S.; Heo, S.W. A novel MobileNet with selective depth multiplier to compromise complexity and accuracy. ETRI J. 2022, 45, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal brain damage. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 November 1989; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty, J.R.; Stanley, R.J.; Almubarak, H.A.; Lama, N.; Kasmi, R.; Guo, P.; Drugge, R.J.; Rabinovitz, H.S.; Oliviero, M.; Stoecker, W.V. Deep learning and handcrafted method fusion: Higher diagnostic accuracy for melanoma dermoscopy images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2019, 23, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Hwang, K.; Sung, W. Structured Pruning of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Syst. 2017, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfed, N.; Khelifi, F.; Bouridane, A.; Seker, H. Pigment network-based skin cancer detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; pp. 7214–7217. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.S.; Gupta, K.; Prasad, P.S. Skin lesion analyser: An efficient seven-way multi-class skin cancer classification using MobileNet. In Proceedings of the Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications: Proceedings of AMLTA 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, R.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L. 3d depthwise convolution: Reducing model parameters in 3d vision tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 32nd Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Canadian AI 2019, Kingston, ON, Canada, 28–31 May, 2019; pp. 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- van der Putten, J.; van der Sommen, F. Influence of decoder size for binary segmentation tasks in medical imaging. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2020: Image Processing, Houston, TX, USA, 15–20 February 2020; pp. 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, V.; Raj, N.I.; Nath, M.K.; Stephen, N. A deep neural network using modified EfficientNet for skin cancer detection in dermoscopic images. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Shah, J.H.; Khan, M.A.; Baili, J.; Ansari, G.J.; Tariq, U.; Kim, Y.J.; Cha, J.-H. A novel framework of multiclass skin lesion recognition from dermoscopic images using deep learning and explainable AI. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1151257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K.M.; Kassem, M.A.; Foaud, M.M. Classification of skin lesions using transfer learning and augmentation with Alex-net. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.; Bhatti, M.H.; Azeem, M. Classification of skin cancer dermoscopy images using transfer learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET), Peshawar, Pakistan, 2–3 December 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Sinha, B.B. Skin Cancer Classification for Dermoscopy Images Using Model Based on Deep Learning and Transfer Learning. In Computational Intelligence and Data Analytics: Proceedings of ICCIDA 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Network with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.00149. [Google Scholar]

- Molchanov, P.; Tyree, S.; Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Kautz, J. Pruning Convolutional Neural Networks for Resource Efficient Inference. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.06440. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, N.; Abozeid, A.; ElHabshy, A.A.; Alzahrani, A. Efficient 3D deep learning model for medical image semantic segmentation. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandola, F.N.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Han, S.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <1MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Denil, M.; Shakibi, B.; Dinh, L.; Ranzato, M.A.; Freitas, N.d. Predicting Parameters in Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 5–10 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jaderberg, M.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Speeding up Convolutional Neural Networks with Low Rank Expansions. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1405.3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Neural Architecture Search with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01578. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Li, Y.; Qiu, X. Nas-unet: Neural architecture search for medical image segmentation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 44247–44257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. Enet: A deep neural network architecture for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.02147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2017; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.F.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2019; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.-S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.M.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Codella, N.C.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (isbi), hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (isic). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combalia, M.; Codella, N.C.; Rotemberg, V.; Helba, B.; Vilaplana, V.; Reiter, O.; Carrera, C.; Barreiro, A.; Halpern, A.C.; Puig, S. Bcn20000: Dermoscopic lesions in the wild. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.02288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotemberg, V.; Kurtansky, N.; Betz-Stablein, B.; Caffery, L.; Chousakos, E.; Codella, N.; Combalia, M.; Dusza, S.; Guitera, P.; Gutman, D. A patient-centric dataset of images and metadata for identifying melanomas using clinical context. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarella, E.; Tion, I.; Zalaudek, I.; Lallas, A.; Athanassios, K.; Longo, C.; Lombardi, M.; Raucci, M.; Satta, R.; Alfano, R.; et al. Both short-term and long-term dermoscopy monitoring is useful in detecting melanoma in patients with multiple atypical nevi. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Adabi, S.; Conforto, S.; Clayton, A.; Podoleanu, A.G.; Hojjat, A.; Avanaki, M.R. An intelligent speckle reduction algorithm for optical coherence tomography images. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology (PHOTOPTICS), Rome, Italy, 27–29 February 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adabi, S.; Rashedi, E.; Clayton, A.; Mohebbi-Kalkhoran, H.; Chen, X.-w.; Conforto, S.; Avanaki, M.N. Learnable despeckling framework for optical coherence tomography images. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 016013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jalilian, E.; Fakhoury, J.W.; Manwar, R.; Michniak-Kohn, B.; Elkin, K.B.; Avanaki, K. Monitoring the topical delivery of ultrasmall gold nanoparticles using optical coherence tomography. Ski. Res. Technol. 2020, 26, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanaki, M.R.; Hojjatoleslami, A. Skin layer detection of optical coherence tomography images. Optik 2013, 124, 5665–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Manwar, R.; Avanaki, K. Miniaturized preamplifier integration in ultrasound transducer design for enhanced photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 3054–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Description | Advantageous | Disadvantageous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pruning [36,37] | Pruning aims to remove unnecessary components of a network, such as weights or neurons, without significantly affecting accuracy. |

|

|

| Knowledge Distillation [38] | Trains a smaller model (student) to mimic the outputs of a larger, pre-trained model (teacher). |

|

|

| Lightweight Architecture Design [20,39,40] | Develop models with efficiency in mind by rethinking the architecture. |

|

|

| Decomposes weight matrices into lower-rank approximations, reducing the number of parameters [41,42] | Decomposes weight matrices into lower-rank approximations, reducing the number of parameters. |

|

|

| Neural Architecture Search (NAS) [43] | Uses automated algorithms to design optimal neural network architectures. |

|

|

| Dataset | Melanoma (Augmented) | Benign (Augmented) | Training Set | Validation Set | Test Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISIC 2017 | 347 (1627) | 1627 (same) | 2602 | 325 | 325 |

| ISIC 2018 | 6705 (8902) | 8902 (same) | 14,244 | 1780 | 1780 |

| ISIC 2019 | 4522 (20,808) | 20,810 (same) | 33,295 | 4161 | 4162 |

| ISIC 2020 | 584 (32,542) | 32,542 (same) | 52,068 | 6508 | 6508 |

| Dataset | Architecture | Number of Parameters | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISIC 2017 | Mobile net | 1,882,498 | 95.36% | 93.85% | 96.90% | 0.9819 |

| 3D-DenseUNet-569 | 802,178 | 54.80% | 69.34% | 40.11% | 0.5676 | |

| Alex-Net Weight pruning | 656,511 | 73.83% | 96.34% | 51.20% | 0.8957 | |

| HU-Net | 1,304,866 | 96.30% | 97.50% | 95.07% | 0.986 | |

| Pocket-Net | 70,114 | 93.55% | 96.90% | 90.20% | 0.977 | |

| APNet | 70,762 | 94.5% | 98.14% | 90.80% | 0.986 | |

| ISIC 2018 | Mobile net | 1,882,498 | 98.90% | 98.20% | 99.56% | 0.9989 |

| 3D-DenseUNet-569 | 802,178 | 95.20% | 93.70% | 96.73% | 0.9648 | |

| Alex-Net Weight pruning | 656,511 | 78.12% | 98% | 58.30% | 0.9457 | |

| HU-Net | 1,304,866 | 98.44% | 99.66% | 97.17% | 0.996 | |

| Pocket-Net | 70,114 | 96.80% | 99.20% | 94.40% | 0.988 | |

| APNet | 70,762 | 97.90% | 99.76% | 96.04% | 0.9908 | |

| ISIC 2019 | Mobile net | 1,882,498 | 96.40% | 94.78% | 98.05% | 0.9917 |

| 3D-DenseUNet-569 | 802,178 | 92.21% | 9.09% | 93.26% | 0.9584 | |

| Alex-Net Weight pruning | 656,511 | 82.75% | 94.40% | 71.14% | 0.9389 | |

| HU-Net | 1,304,866 | 93.80% | 95.36% | 92.24% | 0.976 | |

| Pocket-Net | 70,114 | 91.26% | 96.88% | 85.70% | 0.96 | |

| APNet | 70,762 | 92.6% | 97.27% | 87.9% | 0.965 | |

| ISIC 2020 | Mobile net | 1,882,498 | 99.56% | 99.37% | 99.70% | 0.9999 |

| 3D-DenseUNet-569 | 802,178 | 98.60% | 99.50% | 97.70% | 0.9834 | |

| Alex-Net Weight pruning | 656,511 | 97.75% | 100% | 95.46% | 0.9999 | |

| HU-Net | 1,304,866 | 99.95% | 100.00% | 99.90% | 0.999 | |

| Pocket-Net | 70,114 | 99.20% | 99.76% | 98.73% | 0.999 | |

| APNet | 70,762 | 99.60% | 100% | 99.20% | 0.999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beirami, M.J.; Gruzmark, F.; Manwar, R.; Tsoukas, M.; Avanaki, K. Lightweight Attention-Based Architecture for Accurate Melanoma Recognition. Electronics 2025, 14, 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214281

Beirami MJ, Gruzmark F, Manwar R, Tsoukas M, Avanaki K. Lightweight Attention-Based Architecture for Accurate Melanoma Recognition. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214281

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeirami, Mohammad J., Fiona Gruzmark, Rayyan Manwar, Maria Tsoukas, and Kamran Avanaki. 2025. "Lightweight Attention-Based Architecture for Accurate Melanoma Recognition" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214281

APA StyleBeirami, M. J., Gruzmark, F., Manwar, R., Tsoukas, M., & Avanaki, K. (2025). Lightweight Attention-Based Architecture for Accurate Melanoma Recognition. Electronics, 14(21), 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214281