Compressive Sensing-Based 3D Spectrum Extrapolation for IoT Coverage in Obstructed Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A Novel 3D Spectrum Tensor Completion Framework: We propose a compressive sensing-based framework that effectively addresses the challenge of extrapolating spectrum data into spatially inaccessible urban areas. This is achieved by formulating the 3D spectrum power data as a tensor and vectorizing it, thereby transforming the UAV sampling problem into a sparsity-driven signal recovery problem.

- An Adaptive and Robust Dictionary Learning Mechanism: We introduce the Sparse Coding Neural Gas (SCNG) algorithm, coupled with a neural gas competitive learning strategy, to construct an overcomplete dictionary that is highly adaptive to wide-range spectral fluctuations. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional K-SVD, which often yields underestimated values and converges to poor local minima, thereby ensuring more accurate and robust feature representation.

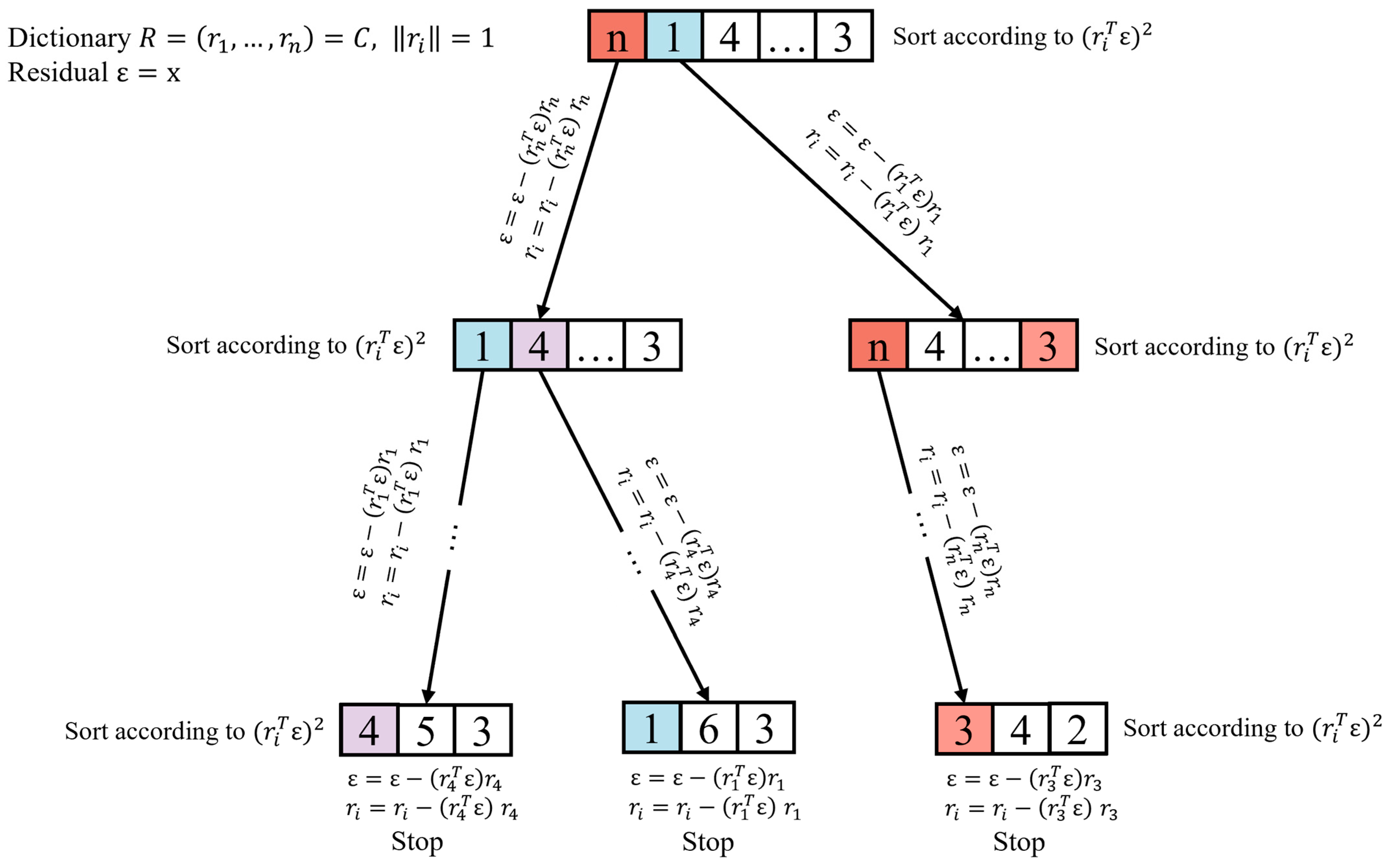

- An Enhanced Sampling and Reconstruction Algorithm: We develop a Bag of Pursuits-optimized Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (BoP-OOMP) framework. This innovation tackles the critical issue of suboptimal atom selection in traditional OMP within highly correlated 3D subspaces. By enabling multi-path tree search and leveraging intermediate solutions for gradient-weighted dictionary updates, our method achieves superior reconstruction accuracy and computational efficiency, effectively decoupling overlapping subspaces.

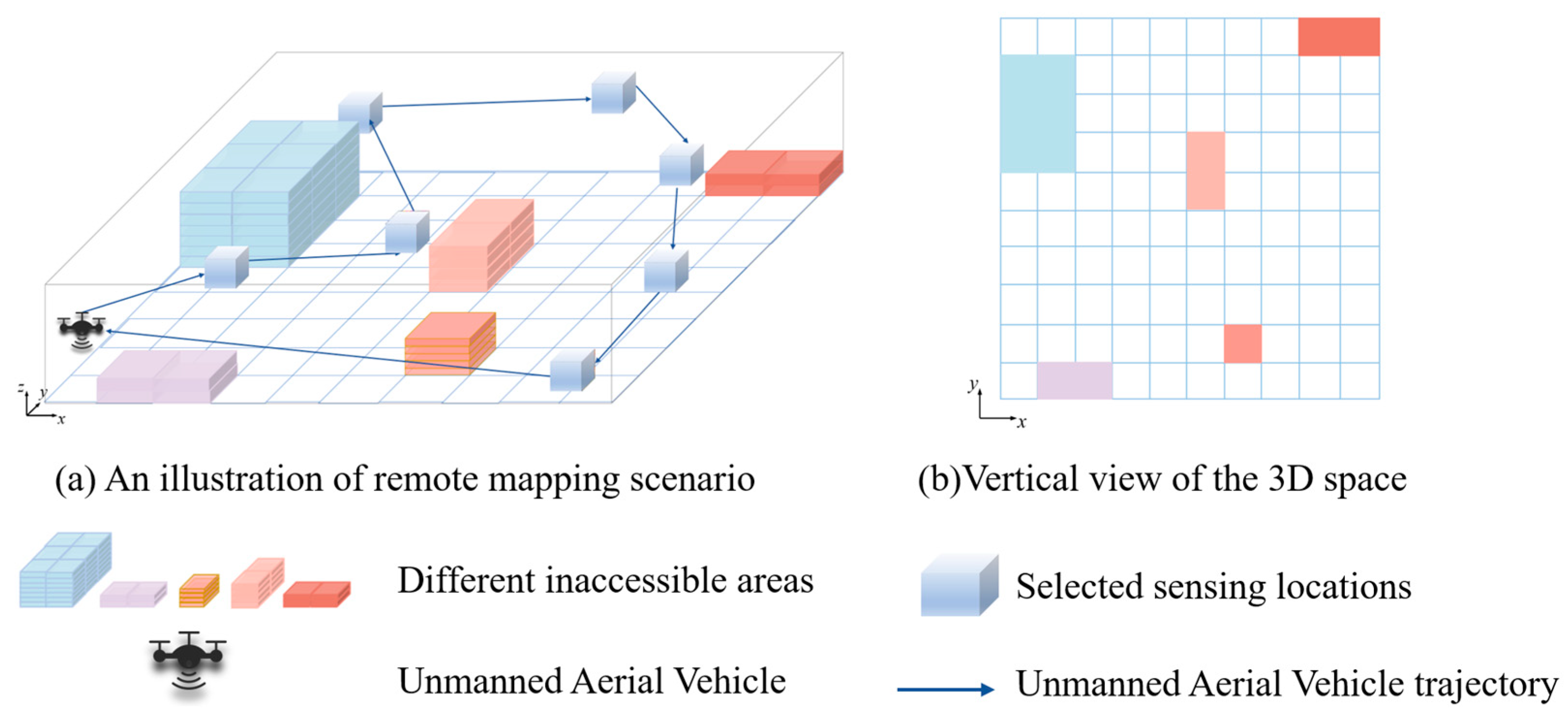

2. System Model

3. Remote Compressed Spectrum Mapping Algorithm

3.1. Optimization of Sampling Matrix Based on Improved Orthogonal Matching Pursuit Algorithm

- Select an appropriate column through ;

- Set ;

- Solve the optimization problem: ;

- Obtain the residual: ;

- Repeat Step 1 until k iterations are completed.

| Algorithm 1 Enhanced Orthogonal Optimized Matching Pursuit (EOOMP) |

| Input: Signal vector y, dictionary matrix , maximum iterations per pursuit: k, user-defined solution count: ; |

| Output: Sparse approximations: (), residual vectors: (); |

| 1: Initialize , , completed pursuits set P ; |

| 2: for to do |

| 3: Initialize pursuit, , , ; |

| 4: for to k − 1 do |

| 5: ; |

| 6: Find where ; |

| 7: Update orthogonal matrix (14); |

| 8: Update residual as (15); |

| 9: Update and set ; |

| 10: if then |

| 11: break inner loop; |

| 12: end if |

| 13: end for |

| 14: Store pursuit result , , P ; |

| 15: if then |

| 16: Find ; |

| 17: Prepare next pursuit starting at pivot , ; |

| 18: Set ; |

| 19: end if |

| 20: end for |

| 21: Return , . |

3.2. Coefficient Determination via Gradient Descent

| Algorithm 2 Rank-Weighted Dictionary Learning with Bag of Pursuits |

| Input: Data samples Y , dictionary , sparsity level , number of candidates , initial neighborhood size , final neihborhood size , initial leaning rate , final learning rate , maximum iterations |

| Output: Learning dictionary D; |

| Initialization: set ; |

| 1: while do |

| 2: Compute annealing parameters: ; |

| 3: Randomly pick an index i from , and set y ; |

| 4: Use Algorithm 1 to obtain K approximations: ; |

| 5: for to K do |

| 6: ; |

| 7: ; |

| 8: end for |

| 9: Sort by ; |

| 10: for to K do |

| 11: ; |

| 12: ; |

| 13: end for |

| 14: ; |

| 15: Updata dictionary: ; |

| 16: Renormalize dictionary columns: ; |

| 17: Increment iteration counter: ; |

| 18: end while |

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Scenario Setup

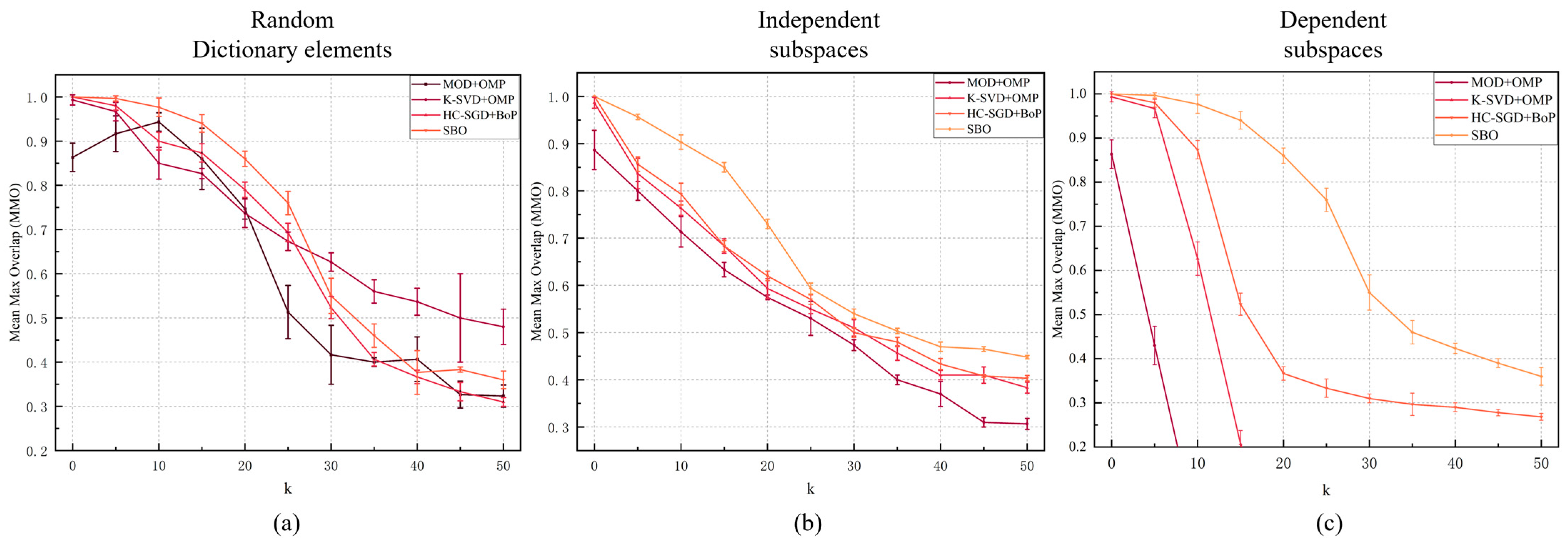

4.2. Spectrum Sampling Position Effectiveness Analysis

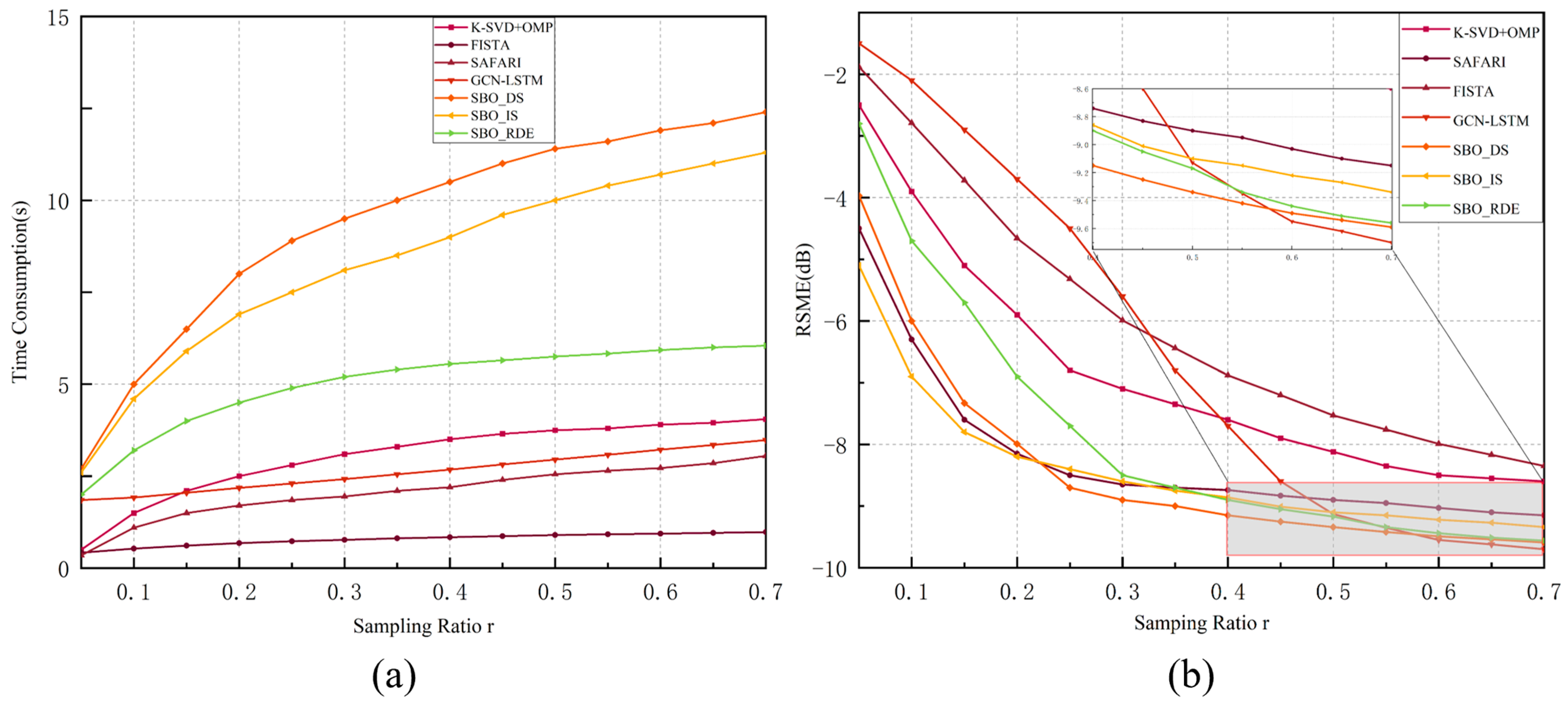

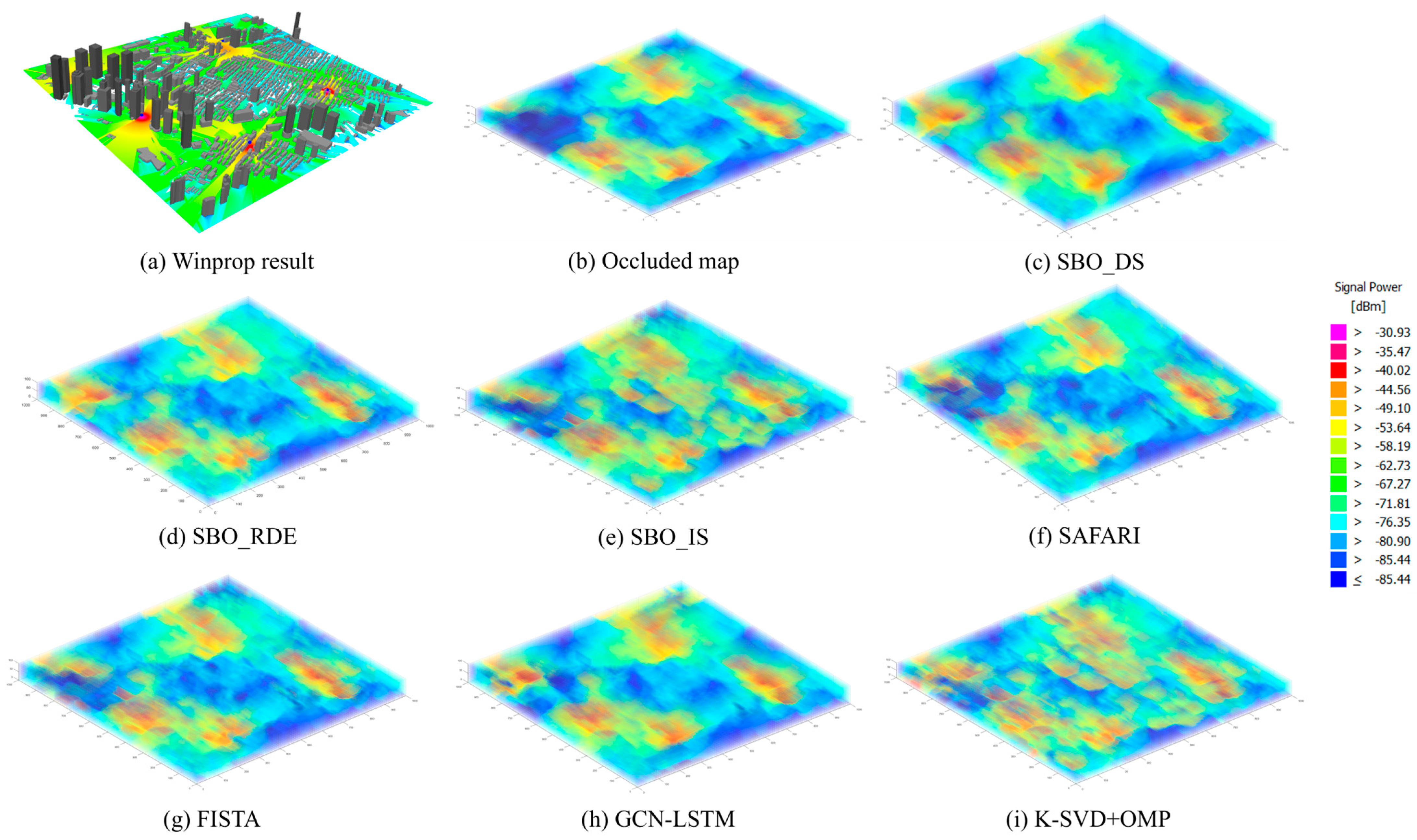

4.3. Comparison of Numerical Performance

4.4. Comparison Performance of Spectrum Situation Estimation

4.5. Computational Complexity Analysis

- SCNG Dictionary Learning. The cost per iteration is , where L is the number of training samples, M is the dictionary size, and n is the signal dimension. The neural gas ranking introduces an additional sorting cost but avoids expensive SVD operations.

- BoP-OOMP Reconstruction. The standard OOMP has a complexity of for recovering a single signal with sparsity k, using a dictionary of size . Our BoP enhancement, which performs K_user-independent pursuits, increases the complexity by a factor of K_user, i.e., . This is the trade-off for achieving higher accuracy and robustness in correlated subspaces.

- Gradient Update. The dictionary update via (35) has a complexity of per sample. While the BoP step increases the computational burden compared to single-path OMP, the significant reduction in the required sampling ratio r (as shown in Figure 5) leads to a much smaller set of measurements y that needs to be processed. This offsets the per-sample complexity and results in a net gain in overall system efficiency for achieving a target reconstruction accuracy.

5. Conclusions

- Computational Complexity: The BoP-OOMP step, involving multiple pursuits, incurs higher computational overhead compared to single-path algorithms like OMP. This may limit its application in strict real-time scenarios without further optimization or hardware acceleration.

- Practical Deployment Issues: The current framework assumes ideal UAV operation. Practical challenges such as UAV flight time, positioning errors, and the impact of UAV itself on the radio environment are not considered in this study and warrant future investigation.

- Model Generalizability: The performance of the dictionary learning is tied to the training data. Its generalization to entirely unseen urban geometries or rapidly time-varying channels requires further validation.

- Global Optimality via Maximum Block Improvement. Joint sampling matrix and sparse vector optimization is investigated using Maximum Block Improvement (MBI) to guarantee global optimality. This coordinate descent approach iteratively updates blocks of variables to escape local optima, particularly effective for non-convex spectrum mapping problems.

- Integrated Radio Map Construction. A complete radio map construction methodology is formed by integrating spectral tensor completion with spatial propagation modeling. This fusion enables simultaneous handling of missing data and physical constraints (e.g., shadowing, multipath) in 3D environments.

- Online and Real-time Algorithm Implementation. Lightweight versions of the SBO algorithm that can run in real time on the limited computational hardware of a UAV, enabling immediate in situ mapping and decision-making, should be investigated. The framework should be extended to handle mobile transmitters and time-varying channel conditions, which requires the dictionary and sampling strategy to adapt continuously during flight.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, W.; Deng, X.; Gui, J.; Zhang, H.; Min, G. Cost-Effective Task Offloading and Resource Scheduling for Mobile Edge Computing in 6G Space-Air–Ground Integrated Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 19428–19442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Leng, S.; He, J.; Zhou, L. Deep-Learning-Based Intelligent Intervehicle Distance Control for 6G-Enabled Cooperative Autonomous Driving. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 15180–15190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriela, W.; Ożadowicz, A. Building information modeling and digital twins for functional and technical design of smart buildings with distributed iot networks—Review and new challenges discussion. Future Internet 2024, 16, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Mobaraki, B.; Lozano-Galant, F.; Soriano, R.P.; Castilla Pascual, F.J. Application of Low-Cost Sensors for Building Monitoring: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Fang, S.; Chu, F.; Fan, Y. Compressed Tensor Completion: Approach for UAV-Aided 3-D Radio Map Construction. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 40516–40531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, P.; Romanik, J.; Golan, E.; Zubel, K. Spectrum awareness for cognitive radios supported by radio environment maps: Zonal approach. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.; Ha, T.N.; Shrestha, R.; Franceschetti, M. Theoretical Analysis of the Radio Map Estimation Problem. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 13722–13737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Peng, Z.; Zheng, S.; Shang, J. Cognitive radio spectrum allocation using evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2009, 8, 4421–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Nan, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Li, J. Three-dimensional ray-tracing-based propagation prediction model for macrocellular environment at sub-6 ghz frequencies. Electronics 2024, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, J. A Novel Random Angular Sampling Method for Spatial and Temporal Channel Emulation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2019, 8, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.; Sicker, D.; Grunwald, D. Bounding the error of path loss models. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks, Aachen, Germany, 3–6 May 2011; pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stine, J.A.; Caicedo Bastidas, C.E. Enabling Spectrum Sharing via Spectrum Consumption Models. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2015, 8, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, K.; Lazarowska, A.; Lisowski, J.; Rybczak, M. A Survey of Machine Learning Methods Applied for Enhancing the Autonomy of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE EUROCON 2025—21st International Conference on Smart Technologies, Gdynia, Poland, 4–6 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, H.; Cao, W. Efficient Cooperative Spectrum Sensing in UAV-Assisted Cognitive Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 7500904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikhani, R.; Keynia, F. Cooperative Spectrum Sensing Meets Machine Learning: Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 1459–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. Machine Learning Empowered Spectrum Sensing Under a Sub-Sampling Framework. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 8205–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Tonchev, K.; Poulkov, V.; Manolova, A.; Vlahov, A. Interpolation Accuracy Evaluation for 3D Radio Environment Maps Construction. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), Tampa, FL, USA, 19–22 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zha, Y.; Wang, H.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J. Novel Radio Environment Map Construction Scheme for 3-D and Full Band for Modern Internet of Things Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 12419–12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, A.; De Maio, A.; Zappone, A.; Razaviyayn, M.; Luo, Z.-Q. A new sequential optimization procedure and its applications to resource allocation for wireless systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Process 2018, 66, 6518–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, D.E.; Kotb, H.; Abbasy, N.H. Improving Power System State Estimation through Physics Informed Deep Learning using Gated Recurrent Units. In Proceedings of the 2024 25th International Middle East Power System Conference (MEPCON), Cairo, Egypt, 17–19 December 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K.; Suto, K.; Inage, K.; Adachi, K.; Fujii, T. Space-Frequency-Interpolated Radio Map. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, H.; Barth, E.; Martinetz, T. Learning Efficient Data Representations with Orthogonal Sparse Coding. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2016, 2, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, K.; Chi, K.; Zhu, Y.H. Cooperative Spectrum Sensing Optimization in Energy-Harvesting Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 7663–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Wang, Z.; Ding, G.; Li, K.; Wu, Q. 3D Compressed Spectrum Mapping with Sampling Locations Optimization in Spectrum-Heterogeneous Environment. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xie, W.; Zhou, X. Cooperative Spectrum Sensing Based on LSTM-CNN Combination Network in Cognitive Radio System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 87615–87625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Da, X.; Hu, H.; Huang, Y.; Cumanan, K. Joint Optimization of Trajectory and Resource Allocation for Time-Constrained UAV-Enabled Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 5576–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, M.; Tan, X. Threshold optimization of cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks. Radio Sci. 2013, 48, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, R.; Wölfle, G.; Jakobus, U. Wave propagation and radio network planning software WinProp added to the electromagnetic solver package FEKO. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Applied Computational Electromagnetics Society Symposium—Italy (ACES), Firenze, Italy, 26–30 March 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- De, P.; Rai, A.; Chatterjee, A. A Projected OMP-Hybridized Discriminative K-SVD-Based Dictionary Learning Algorithm for Human Activity Recognition from Accelerometer Signals. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 38222–38231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labusch, K.; Barth, E.; Martinetz, T. Sparse coding neural gas: Learning of overcomplete data representations. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, M.; Liang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, W.; Lan, T.; Zhang, X.-P. SAFARI: Sparsity-Enabled Federated Learning with Limited and Unreliable Communications. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 4819–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Han, J.; Li, T.; Guo, Z. Fast Independent Component Analysis Denoising for Magnetotelluric Data Based on a Correlation Coefficient and Fast Iterative Shrinkage Threshold Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5916715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M. The Research of Resource Allocation Method Based on GCN-LSTM in 5G Network. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2023, 27, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Ding, G.; Wu, Q. Efficient Remote Compressed Spectrum Mapping in 3-D Spectrum-Heterogeneous Environment with Inaccessible Areas. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description of Meaning |

|---|---|

| Overcomplete Dictionary/Measurement Matrix | |

| Observed Spectrum Signal (Sampled Data) | |

| Sparse Source Signal Coefficient Vector to Be Solved | |

| Sparsity of the Signal (Number of Non-Zero Elements) | |

| Set of Selected Atom Indices in the OOMP Algorithm | |

| Orthogonalized Temporary Dictionary at the n-th Iteration in the j-th Pursuit | |

| Residual After the n-th Iteration in the j-th Pursuit | |

| Index of the Optimal Atom Selected in the Current Iteration | |

| Number of Parallel Pursuit Paths Set in the Bag of Pursuits (BoP) Algorithm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, K.; Fang, S.; Chu, F. Compressive Sensing-Based 3D Spectrum Extrapolation for IoT Coverage in Obstructed Urban Areas. Electronics 2025, 14, 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214177

Yin K, Fang S, Chu F. Compressive Sensing-Based 3D Spectrum Extrapolation for IoT Coverage in Obstructed Urban Areas. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214177

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Kun, Shengliang Fang, and Feihuang Chu. 2025. "Compressive Sensing-Based 3D Spectrum Extrapolation for IoT Coverage in Obstructed Urban Areas" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214177

APA StyleYin, K., Fang, S., & Chu, F. (2025). Compressive Sensing-Based 3D Spectrum Extrapolation for IoT Coverage in Obstructed Urban Areas. Electronics, 14(21), 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214177