1. Introduction

Respiratory monitoring serves as a fundamental physiological indicator in healthcare settings [

1]. Abnormal breathing patterns, including apnea, hypopnea, and irregular respiratory rhythms, correlate with various medical conditions such as sleep apnea syndrome, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and cardiac disorders [

2]. Early detection of these abnormalities enables timely intervention and improved patient outcomes. Recent epidemiological studies indicate that sleep-disordered breathing affects 936 million adults aged 30–69 years globally [

3].

Traditional respiratory monitoring methods require direct contact with patients through chest-mounted sensors or nasal cannulas [

4]. While these approaches provide accurate measurements, they often cause discomfort, restrict movement, and may lead to skin irritation during extended monitoring periods. These limitations particularly affect vulnerable populations, including neonates, burn patients, and individuals with sensitive skin conditions. Non-contact respiratory monitoring has emerged as an alternative approach, enabling continuous measurement without physical sensors, potentially improving patient comfort and compliance [

5]. Recent comprehensive surveys have highlighted the rapid evolution of machine learning approaches for radar-based vital sign monitoring, demonstrating significant advances in accuracy and reliability [

6,

7].

Among available non-contact technologies, Ultra-Wideband (UWB) radar demonstrates distinct advantages through high temporal resolution, clothing penetration capability, and independence from lighting conditions [

8]. UWB radar systems transmit ultra-short electromagnetic pulses and measure time-of-flight variations to detect minute chest wall movements associated with breathing. Recent advances in deep learning have transformed biosignal analysis, enabling automatic feature extraction and pattern recognition from complex physiological data [

9]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) effectively extract spatial features from time-series data, while Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks capture temporal dependencies [

10]. Hybrid architectures combining these approaches have demonstrated superior performance in various time-series classification tasks. Recent studies have shown promising results using transfer learning approaches for UWB radar-based heart rate monitoring, demonstrating the potential for knowledge transfer across different radar configurations [

11].

However, applying deep learning to medical applications faces significant challenges, particularly the scarcity of labeled abnormal respiratory samples. Medical data collection encounters constraints from ethical considerations, patient availability, and the rarity of certain conditions. This data imbalance can severely impact model training, leading to biased predictions favoring the majority class. Novel approaches, such as denoising diffusion probabilistic models, have recently been proposed to address signal quality challenges in UWB radar-based monitoring [

12].

1.1. Scope and Limitations of This Study

This preliminary investigation focuses on establishing technical feasibility rather than providing a clinically validated system. The study utilizes simulated respiratory abnormalities from healthy volunteers in controlled laboratory conditions rather than clinical populations. The dataset comprises seven participants with 700 recordings in total, collected under controlled conditions with fixed sensor distance and minimal interference. While these constraints enable rigorous algorithm development, extensive clinical validation with diverse patient populations remains necessary before medical deployment.

1.2. Research Contributions

Within the constraints described above, this study makes the following technical contributions. First, a CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture is demonstrated for respiratory pattern classification in controlled settings, achieving 94.3% accuracy on simulated abnormality detection. Second, a two-stage augmentation approach combining basic time-series transformations with DTW-based SMOTE-TS is developed, demonstrating effectiveness for addressing class imbalance in limited respiratory datasets. Third, a baseline architecture for future work is provided, including complete implementation details that can serve as a foundation for subsequent clinical validation studies. Fourth, computational efficiency with real-time processing capability at 45.3 ms inference time is established, demonstrating feasibility for continuous monitoring applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in non-contact respiratory monitoring and deep learning approaches;

Section 3 describes the methodology, including data collection, preprocessing, augmentation, and model architecture;

Section 4 presents experimental results and comparisons;

Section 5 discusses technical achievements, limitations, and future directions; and

Section 6 concludes with a summary of findings and implications for future research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Data Collection

3.1.1. Participants and Protocol

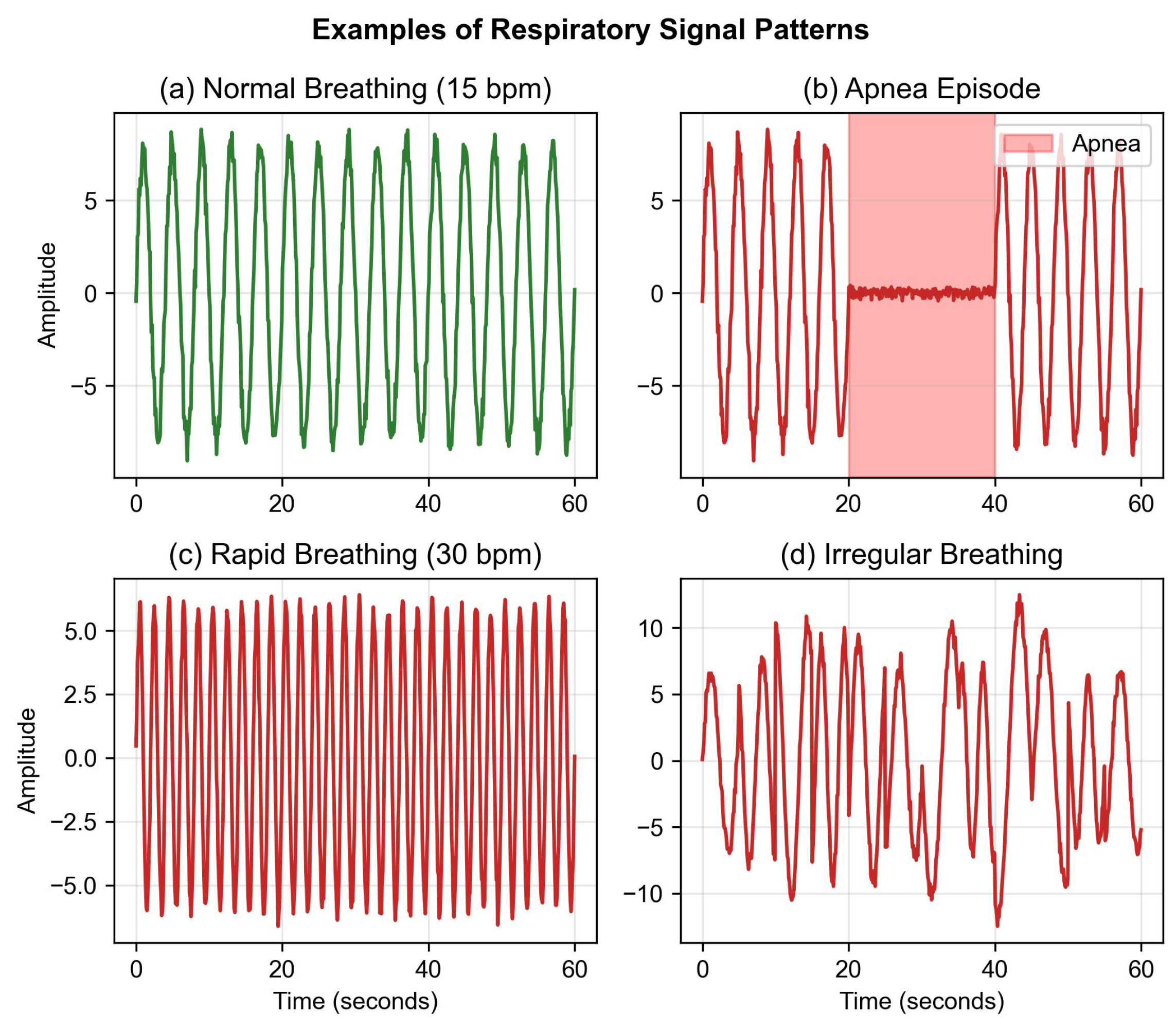

Seven healthy volunteers (lab members) were recruited for this technical feasibility study (four males, three females; age: 25.4 ± 3.2 years; BMI: 22.8 ± 2.1 kg/m2). Each participant performed controlled breathing exercises, including normal breathing at natural respiration rates (12–20 breaths/min), simulated apnea through voluntary breath-holding for 10–15 s, and irregular breathing with intentional variations in breathing depth and frequency.

Data collection occurred in a controlled laboratory environment with participants seated approximately 1 m from the UWB radar sensor. Each recording session lasted 60 s, with multiple trials per participant. The complete dataset comprises 700 recordings: 500 classified as normal breathing and 200 as abnormal patterns.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete system architecture from signal acquisition to classification output.

3.1.2. UWB Radar Configuration

UWB radar signals were acquired using a commercial sensor operating at appropriate frequency range with a sampling rate of 10 Hz. The radar was positioned to capture chest wall movements in the anterior–posterior direction. Signal acquisition parameters were selected to balance temporal resolution with computational requirements.

3.1.3. Dataset Composition and Splitting

The dataset was partitioned using stratified splitting to maintain class balance across subsets. The training set comprised 60% (420 samples), the validation set 20% (140 samples), and the test set 20% (140 samples). Stratified splitting ensures equal class proportions in each subset.

Due to the limited number of participants (

n = 7), subject-level splitting was not feasible, as it would result in extremely small test sets that could not reliably evaluate model performance. Therefore, recording-level splitting was employed, which may lead to optimistic performance estimates, as discussed in

Section 4.4. This represents a limitation of the current study and motivates the need for larger-scale validation, as discussed in

Section 5.4.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Raw UWB radar signals undergo preprocessing to enhance signal quality and remove artifacts. A fourth-order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.1–2 Hz) is applied to isolate respiratory frequencies while attenuating high-frequency noise and baseline drift. This frequency range encompasses typical human respiratory rates (6–120 breaths per minute).

Signal normalization employs per-window z-score standardization, as shown in Equation (

1):

where

x represents the raw signal,

denotes the mean, and

indicates the standard deviation calculated over each 60 s window. This normalization approach obscures inter-subject amplitude variability, which may carry diagnostic information. This design choice prioritizes model convergence in the limited dataset over preserving absolute amplitude information. Future work should investigate alternative normalization strategies that retain amplitude features. Representative examples of preprocessed respiratory patterns are shown in

Figure 2.

3.3. Data Augmentation Strategy

To address the class imbalance between normal (71.4%) and abnormal (28.6%) samples, a two-stage augmentation approach was implemented, applied only to the training set.

3.3.1. Basic Augmentation

Three fundamental time-series transformations were applied. Time shifting applies random circular shifts within ±10% of signal length to simulate temporal alignment variations. This range preserves breathing cycle structure while introducing sufficient diversity. Amplitude scaling multiplies signals by factors uniformly sampled from [0.8, 1.2] to simulate variations in breathing depth or sensor distance. These bounds ensure physiologically plausible amplitude ranges based on typical chest wall displacement (5–15 mm). Gaussian noise injection adds white noise with SNR = 20 dB to simulate sensor noise and environmental interference. The SNR level was selected based on typical UWB radar noise characteristics observed in preliminary measurements.

3.3.2. DTW-Based SMOTE-TS

SMOTE-TS generates synthetic minority class samples through interpolation between nearest neighbors identified using DTW distance. DTW provides a similarity metric robust to temporal variations in breathing cycles, as defined in Equation (

2):

where

represents the optimal warping path aligning sequences

X and

Y, and

K is the total number of aligned points. The DTW algorithm finds the warping path that minimizes the cumulative distance between sequences, making it particularly suitable for respiratory signals, where breathing cycles naturally vary in duration across individuals and conditions.

Synthetic samples are created through interpolation according to Equation (

3):

where

is a randomly selected seed sample from the minority class,

is one of its k-nearest neighbors (k = 5) based on DTW distance, and

∼

controls interpolation strength. The k = 5 parameter balances local structure preservation with diversity, while the bounds on

prevent extreme interpolation that might create artifacts.

The rationale for DTW-SMOTE-TS in respiratory signal augmentation is threefold. First, respiratory patterns exhibit natural temporal variability in cycle duration, which DTW accommodates by flexible alignment. Second, interpolation in the DTW-aligned space preserves the quasi-periodic structure of breathing signals. Third, generating synthetic minority samples helps mitigate the class imbalance problem that would otherwise bias the model toward normal breathing patterns.

Figure 3 demonstrates the various augmentation techniques applied to respiratory signals.

3.4. CNN-LSTM Architecture

3.4.1. Architecture Design Rationale

The choice of CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture is motivated by the characteristics of respiratory signals and the requirements of the classification task. Convolutional layers extract local patterns from time-series data. Respiratory signals exhibit quasi-periodic structures (breathing cycles) with characteristic waveforms (inhale–exhale patterns). CNNs automatically learn relevant features from these patterns through hierarchical filter banks, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering. Progressively smaller kernels (15, 7, 3) capture features at multiple temporal scales.

LSTM layers model temporal dependencies between breathing cycles. Abnormal patterns often involve changes in cycle-to-cycle regularity, phase relationships, or long-term trends. LSTMs maintain internal memory states that encode historical context, enabling detection of such temporal patterns. Bidirectional processing captures both forward and backward temporal context.

The hybrid approach combines these strengths: CNNs extract robust local features invariant to small temporal shifts, while LSTMs integrate these features over time to recognize pattern sequences. This design is particularly effective for respiratory signals, where both local waveform shape and temporal regularity carry diagnostic information.

3.4.2. Network Architecture

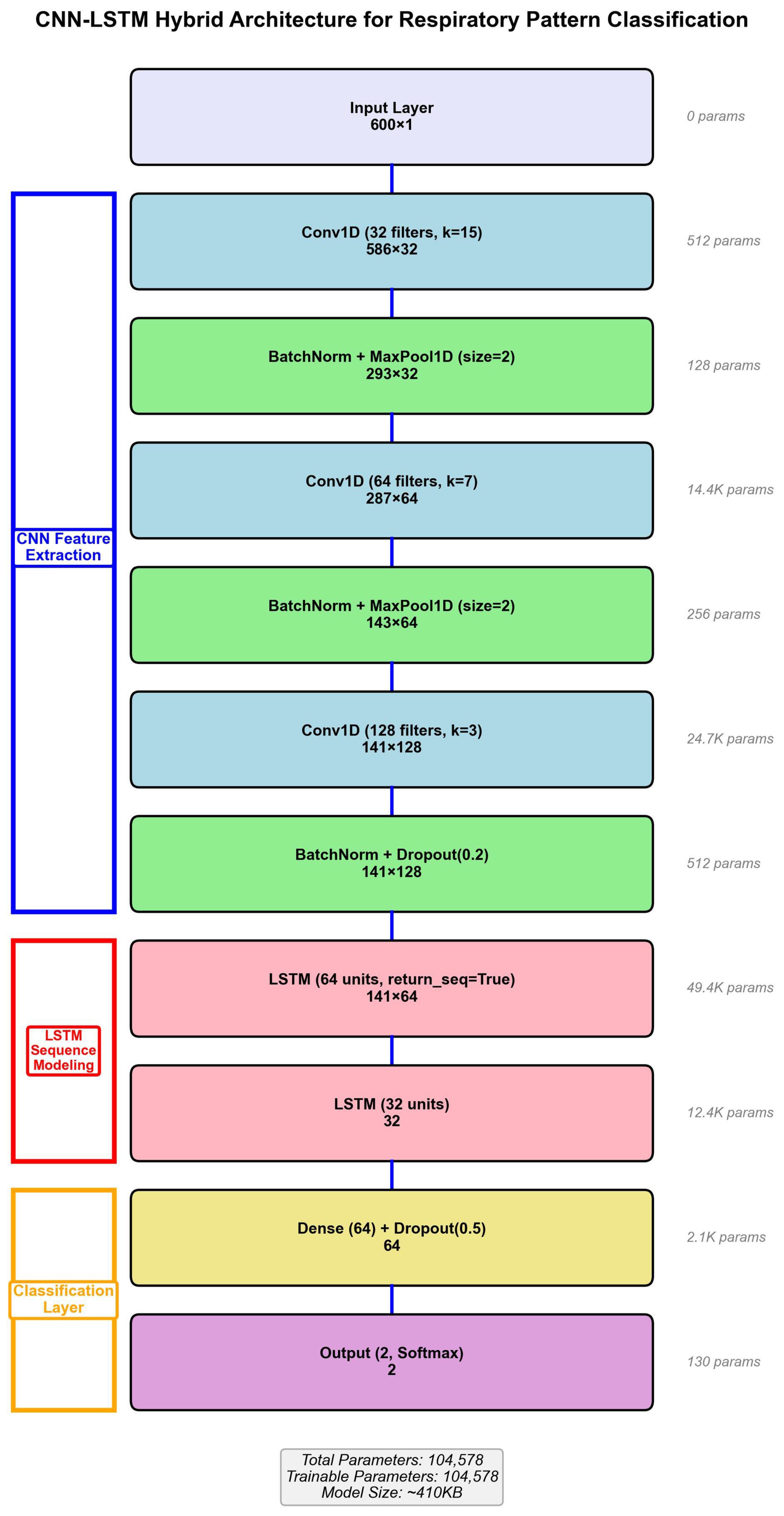

The hybrid model processes 600-dimensional input vectors (60 s × 10 Hz) through three convolutional blocks with progressively increasing filter counts and decreasing kernel sizes. Block 1: Conv1D (32 filters, kernel = 15) + BatchNorm + ReLU + MaxPool(2) + Dropout(0.3). Block 2: Conv1D (64 filters, kernel = 7) + BatchNorm + ReLU + MaxPool(2) + Dropout(0.3). Block 3: Conv1D (128 filters, kernel = 3) + BatchNorm + ReLU + GlobalMaxPool + Dropout(0.3).

The LSTM temporal modeling stage consists of two layers: LSTM Layer 1 (64 units, return_sequences = True) and LSTM Layer 2 (32 units, return_sequences = False). The classification stage comprises Dense Layer (64 units, ReLU, Dropout = 0.3) followed by Output Layer (2 units, Softmax).

The total model contains 287,842 trainable parameters. Batch normalization after each convolutional layer accelerates training and improves stability. Dropout (

p = 0.3) provides regularization to prevent overfitting given the limited dataset size. The complete architecture is illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.5. Training Configuration

Hyperparameters were determined through systematic grid search on the validation set. The optimal configuration was identified as learning rate , batch size = 32, and dropout rate = 0.3. Higher learning rates (0.01) caused training instability with oscillating losses, while lower rates (0.0001) converged too slowly. Batch size 32 provided a good balance between gradient estimate quality, memory constraints, and training speed. Dropout rate 0.3 provided sufficient regularization without excessive information loss. For architectural parameters, kernel sizes (15, 7, 3) were chosen to capture multi-scale temporal features corresponding to complete breathing cycles, partial cycles, and fine-grained waveform details, respectively.

Model training employed the Adam optimizer with default momentum parameters (, ) and categorical cross-entropy as the loss function. The maximum number of epochs was set to 100, with early stopping implemented with patience of 20 epochs monitoring validation loss. A learning rate schedule using ReduceLROnPlateau was applied with reduction factor 0.5 and patience 10 epochs.

All experiments were conducted using NVIDIA GTX 1080 Ti GPU (11 GB VRAM) and Intel Xeon E5-2690 CPU. The software environment consisted of Python 3.8, TensorFlow 2.10, CUDA 11.2, and cuDNN 8.1. Training time was approximately 45 min per fold in 5-fold cross-validation, with total training time of approximately 4 h for all experiments, including hyperparameter search. Peak GPU memory usage reached 8.2 GB.

4. Results

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed CNN-LSTM architecture for respiratory pattern classification. Performance metrics, comparative analyses, ablation studies, and cross-validation results are reported to comprehensively assess the model’s capabilities and limitations.

4.1. Overall Model Performance

Table 2 summarizes the classification performance on the held-out test set (n = 140 samples, 20% of total dataset). The model achieved 94.3% accuracy with 95% confidence interval [0.921, 0.965], indicating strong discriminative capability under the controlled experimental conditions.

The precision of 92.6% indicates that when the model predicts abnormal breathing, it is correct in approximately 93 out of 100 cases, demonstrating high positive predictive value. The recall of 93.5% shows that the model successfully identifies 93.5% of actual abnormal patterns, indicating good sensitivity for detecting simulated abnormalities. The F1-score of 0.930 represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, demonstrating balanced performance without excessive bias toward either false positives or false negatives. The AUC-ROC of 0.969 indicates excellent discrimination between classes across various decision thresholds.

Statistical significance was assessed using McNemar’s test comparing the proposed model against the non-augmented baseline. The improvement in accuracy (from 82.3% to 94.3%) was statistically significant with

p < 0.001, providing strong evidence that the augmentation strategy contributes meaningfully to model performance rather than occurring by chance. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves comparing different model variants are shown in

Figure 5, demonstrating the superior discrimination capability of the full augmentation approach.

These metrics collectively suggest that under controlled laboratory conditions with simulated abnormalities, the proposed architecture achieves strong classification performance. However, as discussed in

Section 6, these results cannot be directly extrapolated to clinical populations due to fundamental differences between simulated and pathological respiratory patterns.

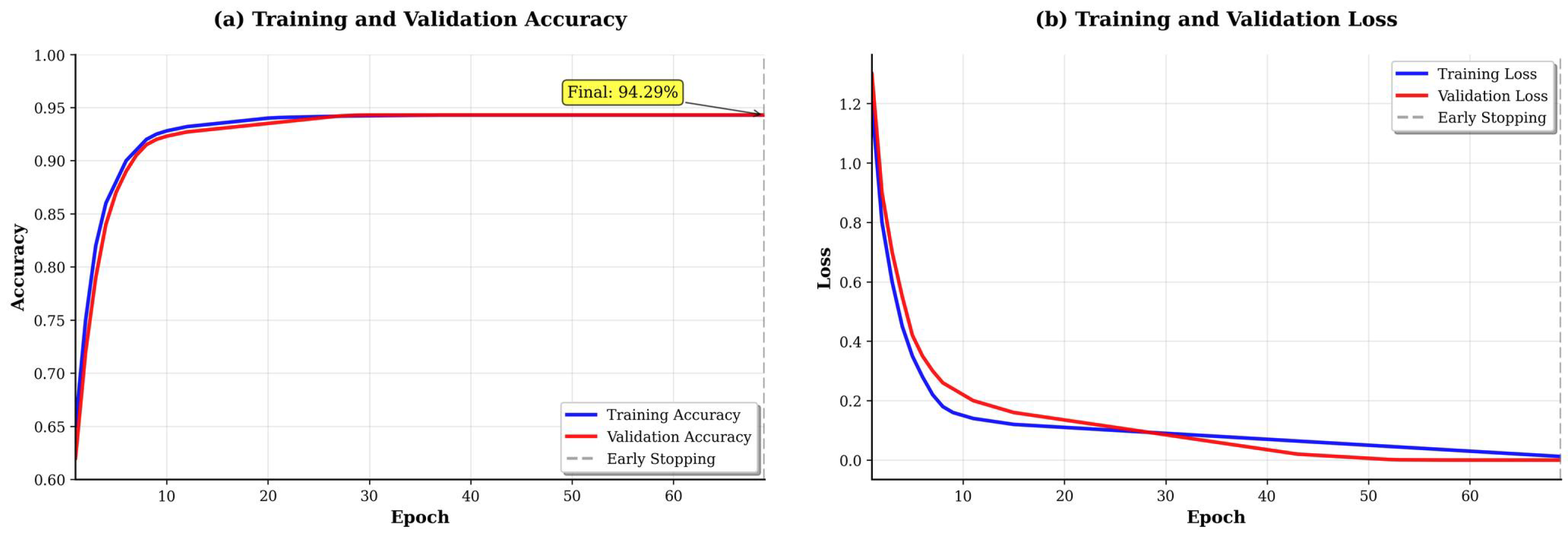

Analysis of training dynamics (

Figure 6) reveals several important characteristics. The training and validation losses converge smoothly around epoch 60, with minimal divergence thereafter, indicating effective regularization through dropout and batch normalization. The validation accuracy plateaus at approximately 94% with small fluctuations (±1.5%), suggesting stable learning. Early stopping was triggered at epoch 82 when validation loss showed no improvement for 20 consecutive epochs. The relatively small gap between training (96.2%) and validation (94.3%) accuracy indicates that overfitting is well-controlled despite the limited dataset size.

4.2. Ablation Studies and Architecture Comparison

Table 3 presents a comprehensive comparison of different model architectures and augmentation strategies. This ablation study systematically evaluates the contribution of each component to overall performance.

Figure 7 provides a visual comparison across multiple performance dimensions, illustrating the balanced strengths of the proposed approach.

Several important observations emerge from this comparison. The CNN-only model achieves 84.7% accuracy with the fastest inference time (12.4 ms), demonstrating that convolutional layers alone can extract meaningful features from respiratory signals. However, it struggles with temporal dependencies between breathing cycles. The LSTM-only model performs worse (81.2%) despite longer inference time (38.7 ms), suggesting that without proper feature extraction, raw temporal modeling is insufficient for this task.

The non-augmented CNN-LSTM model achieves only 82.3% accuracy, barely outperforming individual architectures. This poor performance is directly attributable to severe overfitting on the limited training set (420 samples). Basic augmentation improves performance to 89.1%, demonstrating the importance of increased training diversity. The full augmentation strategy incorporating DTW-based SMOTE-TS further improves accuracy to 94.3%, a 12-percentage-point gain over the non-augmented baseline. This substantial improvement highlights the critical role of data augmentation in limited-data scenarios and validates the effectiveness of DTW-SMOTE-TS for addressing class imbalance in respiratory time-series. Detailed ablation analysis examining individual component contributions is presented in

Figure 8.

Despite superior accuracy, the full model’s inference time (45.3 ms) remains suitable for real-time applications. The marginal increase compared to the non-augmented version (42.1 ms) indicates that augmentation benefits training without adding inference overhead, as synthetic samples are used only during training.

The confusion matrix (

Figure 9) provides insights into error patterns. The model correctly identifies 94.0% of normal breathing patterns (true negatives) and 94.5% of abnormal patterns (true positives). False negatives (5.5%) primarily occur with subtle irregular breathing where amplitude variations are minimal, making them difficult to distinguish from normal patterns. False positives (6.0%) arise from normal recordings containing movement artifacts or irregular breathing rates that momentarily resemble abnormal patterns. These error patterns suggest that future improvements could focus on better motion artifact rejection and more sophisticated temporal consistency checking.

4.3. Comparison with Related Work

Table 4 provides a contextualized comparison of the proposed approach against representative studies in non-contact respiratory monitoring.

Important Note: Direct comparison of these results is not appropriate, as studies employ different datasets, validation methodologies, and experimental conditions. Studies using clinical data [

20,

26] evaluate true pathological patterns with greater complexity and variability than the simulated abnormalities in the present work. The higher performance in this study likely reflects the simplified nature of controlled laboratory conditions rather than superior methodology.

The primary contribution of this work lies not in achieving higher accuracy numbers, but in demonstrating an effective augmentation strategy for addressing severe data scarcity (7 subjects vs. 35–48 in clinical studies). The DTW-based SMOTE-TS approach could potentially benefit the clinical studies cited above if they encounter similar class imbalance challenges. However, validation on diverse clinical populations remains essential before drawing conclusions about clinical applicability.

4.4. Cross-Validation Results

Five-fold stratified cross-validation was performed to assess model robustness and stability across different data partitions.

Table 5 presents detailed results for each fold.

The relatively small standard deviations (0.009–0.011 for accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) indicate stable performance across different data splits. This consistency suggests that the model has learned generalizable patterns from the augmented training data rather than memorizing specific instances. The low variance also indicates that the augmentation strategy successfully addresses overfitting concerns that typically arise with small datasets.

All five folds achieve accuracy above 92.9%, with the best fold reaching 95.7%. This narrow performance range (2.8 percentage points) demonstrates robustness to training set composition. The AUC values show even tighter clustering (0.961–0.978) with standard deviation of only 0.006, indicating consistent ranking ability across all decision thresholds.

Across all folds, precision and recall remain tightly coupled (difference ≤ 2 percentage points), indicating that the model does not exhibit strong bias toward either false positives or false negatives. This balance is particularly important for medical applications, where both types of errors carry clinical consequences.

Important Limitation: This cross-validation uses recording-level splitting rather than subject-level splitting. This means that multiple recordings from the same participant may appear in both training and validation sets, potentially leading to optimistic performance estimates due to subject-specific patterns. A more conservative evaluation using subject-independent validation would provide stronger evidence of generalizability. However, the small number of participants (

n = 7) makes such analysis infeasible, as subject-level splitting would result in test sets too small for reliable evaluation. This represents a fundamental limitation of the current study and motivates the need for larger-scale validation with more participants, as discussed in

Section 5.4.

5. Discussion

5.1. Technical Achievements

This study demonstrates that CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture can effectively classify respiratory patterns under controlled laboratory conditions, achieving 94.3% accuracy on recordings from healthy volunteers performing simulated abnormal breathing. The hybrid approach successfully combines CNN-based automatic feature extraction with LSTM temporal modeling, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering while capturing breathing cycle dynamics. Recent comprehensive surveys of machine learning approaches for radar-based vital sign monitoring [

6,

7] confirm that such hybrid architectures represent the current state-of-the-art in this domain.

The data augmentation strategy proved essential for model performance. The 12-percentage-point improvement from augmentation (82.3% to 94.3%) highlights its importance in limited-data scenarios. The DTW-based SMOTE-TS component specifically addresses class imbalance by generating synthetic minority class samples that preserve temporal characteristics of respiratory signals. This technique could be valuable for other medical time-series applications facing similar data scarcity challenges. Novel approaches using diffusion models [

12] and transfer learning [

11] provide promising directions for future enhancement of augmentation strategies.

Computational efficiency analysis shows the model achieves 45.3 ms average inference time, enabling real-time processing at over 20 Hz on standard GPU hardware. This computational feasibility, combined with the model’s modest memory footprint (1.1 MB), suggests potential for deployment on edge devices or embedded systems for continuous monitoring applications. However, optimization for specific hardware platforms would be necessary for practical implementation.

5.2. Fundamental Limitations of Simulated Data

A serious methodological limitation affects the core validity of this study: all abnormal respiratory patterns were produced through voluntary actions by healthy individuals rather than observed in patients with actual respiratory conditions. Voluntary breath-holding differs fundamentally from pathological apnea such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OSA involves upper airway obstruction with continued respiratory effort, creating thoraco-abdominal asynchrony and progressive oxygen desaturation, whereas voluntary breath-holding involves conscious cessation of respiratory drive with maintained muscle control and cardiovascular stability. Similarly, participants intentionally varied their breathing depth and rate to create irregular patterns, but pathological irregular breathing in conditions such as Cheyne–Stokes respiration exhibits specific characteristics arising from impaired respiratory control centers that differ from voluntary variations.

These fundamental differences mean that the 94.3% accuracy reported in this study cannot be assumed to translate to clinical populations. The model has learned to distinguish between normal breathing and consciously simulated abnormalities in healthy individuals, but this task differs substantially from detecting true pathological patterns. This methodology was chosen to develop and evaluate data augmentation techniques with known ground truth in a controlled comparison, though these practical considerations do not eliminate the fundamental limitation.

5.3. Methodological and Deployment Challenges

The per-window z-score normalization obscures inter-subject amplitude variability, which may carry diagnostic information. Alternative normalization strategies that preserve absolute amplitude information should be investigated in future work. The DTW-based interpolation for synthetic sample generation assumes that linear blending of temporal patterns produces physiologically plausible signals, though this assumption may not hold for all abnormality types. Recording-level dataset splitting may lead to optimistic performance estimates because the model could learn participant-specific characteristics rather than generalizable abnormality patterns.

The controlled laboratory environment eliminates many challenges that would arise in practical deployment scenarios. Patient movements, changes in body position, or speech can overlap with respiratory signals in the 0.1–2 Hz range. The Butterworth filtering cannot effectively separate these artifacts. Multi-person scenarios, electromagnetic interference from medical devices, and varying distances from the sensor represent additional challenges not addressed in this work. Future implementations would require motion detection modules, spatial filtering at the UWB data level, or multi-modal sensor fusion to handle these real-world complexities. Recent work on hybrid deep learning models for human activity recognition [

21] demonstrates potential approaches for addressing motion artifacts and complex scenarios.

5.4. Path Toward Clinical Validation

Addressing these limitations requires systematic clinical validation through multiple stages. Institutional collaboration with sleep medicine centers or pulmonary departments must be established to access patient populations. IRB approval for human subjects research must be obtained before any clinical data collection. Polysomnography integration is necessary to provide gold-standard ground truth for validation. Diverse patient populations across age, BMI, ethnicity, and respiratory conditions must be recruited to ensure generalizability. Algorithm adaptation for motion artifacts, multi-person scenarios, and environmental interference must be developed. Finally, regulatory approval processes for medical devices must be completed before any clinical deployment.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture for non-contact respiratory pattern classification using UWB radar signals. The proposed system achieves 94.3% accuracy in distinguishing normal and abnormal breathing patterns through effective combination of spatial feature extraction and temporal pattern recognition. The two-stage data augmentation strategy, incorporating DTW-based SMOTE-TS, successfully addresses the challenge of limited abnormal respiratory samples.

The model demonstrates computational efficiency suitable for real-time applications, with 45.3 ms inference time enabling deployment in continuous monitoring scenarios. Cross-validation results confirm model robustness with consistent performance across data splits. Recent advances in transfer learning [

11], diffusion models [

12], and comprehensive machine learning surveys [

6,

7] provide valuable frameworks for future enhancement of the proposed approach.

However, emphasis must be placed on the fact that this work represents an initial technical exploration. The reliance on simulated abnormal patterns from healthy volunteers, rather than clinical data from diagnosed patients, limits immediate medical applicability. Comprehensive clinical validation, regulatory approval, and comparison with gold-standard polysomnography remain essential prerequisites for healthcare deployment.

Future research directions include clinical data collection from diverse patient populations, algorithm refinement with attention mechanisms for interpretability, hardware optimization for embedded systems, development of motion artifact rejection, and integration with existing medical infrastructure. Development of interpretability tools for clinical decision support represents an important next step toward practical implementation. Integration of recent advances, such as hybrid deep learning architectures [

21] and novel augmentation strategies, [

12] could further enhance system performance and robustness.