An Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy for Microservices Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Analysis

2.1. Threat Model

2.2. Key Challenges

3. Problem Modeling

3.1. Microservice Attack Graph Model

3.2. Security Quantification Model

3.3. QOS Model

3.4. Defense Effectiveness Definition

4. AD2S Strategy Framework

4.1. The Overall Framework of AD2S

4.2. Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy Optimization Algorithm Based on DQN

| Algorithm 1. Optimal Security Defense Strategy Optimization Algorithm Based on DQN. |

| Input: , User request arrival rate |

| Output: Neural network parameters |

| 1. Initialization: neural network parameter , the experience replay pool , discount factor , learning rate , greed coefficient , the number of empirical samples , target network update step . |

| 2. for episode in range (STEPS) do |

| 3. Under the initial conditions, the microservice security defense configuration is randomly generated |

| 4. Generate the initial microservice state vector in combination with the runtime status |

| 5. |

| 6. if do |

| 7. |

| 8. end if |

| 9. Randomly select an action with a probability of , otherwise select |

| 10. Modify the defense configuration vector based on action to reach the next state |

| 11. Calculate the reward based on Equation (13) |

| 12. Store the obtained sample experience in |

| 13. if do |

| 14. Collect batch samples from D, calculate the loss function based on Formula (14), and update the network parameters using the gradient descent method |

| 15. end if |

| 16. Use Equations (14) and (15) to perform the gradient descent method and update the network parameters |

| 17. if do |

| 18. Update the parameters of the target network |

| 19. end if |

| 20. Update the parameters of the target network |

| 21. end for |

| 22. Obtain the optimal microservice security defense configuration |

5. Experimental Results and Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

5.2. Comparative Strategies

5.3. Result Analysis

5.3.1. Convergence Evaluation of the DQN Algorithm

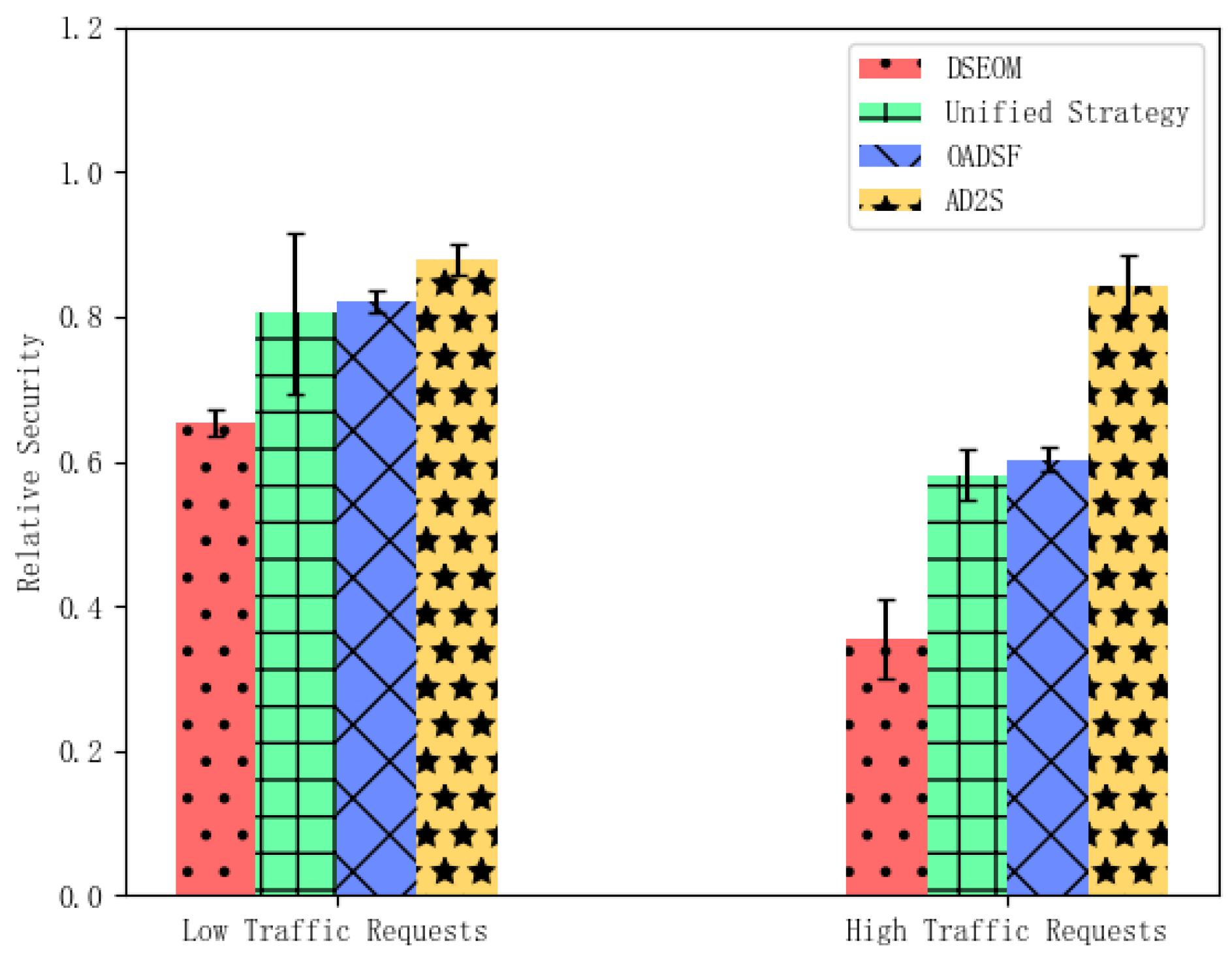

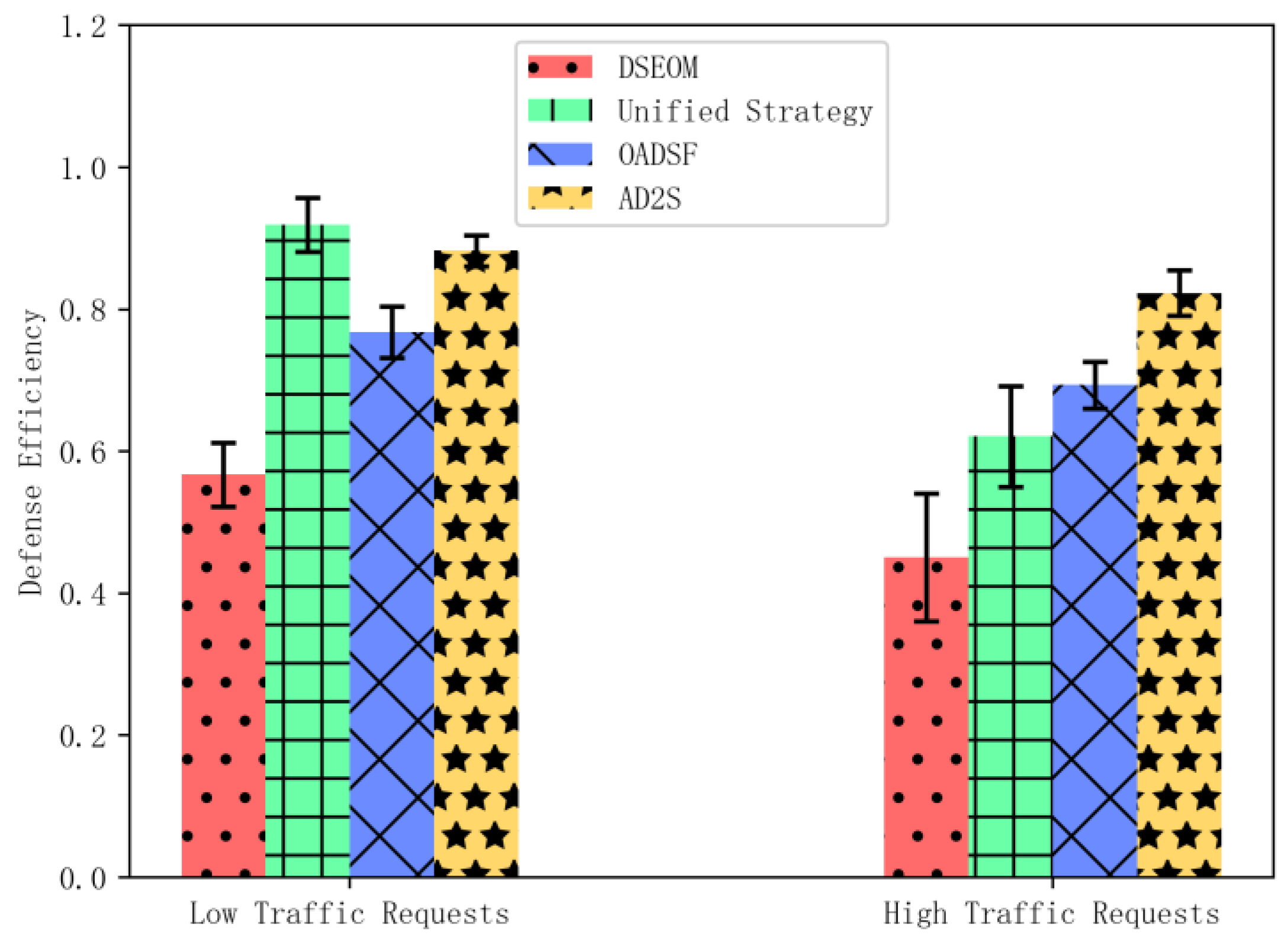

5.3.2. Defense Effectiveness Evaluation of AD2S

5.3.3. Usability and Scalability Evaluation of AD2S

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, X.; Peng, X.; Xie, T.; Sun, J.; Ji, C.; Li, W.H.; Ding, D. Fault Analysis and Debugging of Microservice Systems: Industrial Survey, Benchmark System, and Empirical Study. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 47, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abgaz, Y.; McCarren, A.; Elger, P.; Solan, D.; Lapuz, N.; Bivol, M.; Jackson, G.; Yilmaz, M.; Buckley, J.; Clarke, P. Decomposition of Monolith Applications Into Microservices Architectures: A Systematic Review. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 4213–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Doghman, F.; Moustafa, N.; Khalil, I.; Sohrabi, N.; Tari, Z.; Zomaya, A.Y. AI-Enabled Secure Microservices in Edge Computing: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qassem, L.M.; Stouraitis, T.; Damiani, E.; Elfadel, I.M. Containerized Microservices: A Survey of Resource Management Frameworks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 3775–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Steenkamer, B.; Gu, Z.S.; Kayaalp, M.; Pendarakis, D.; Wang, H.N. A Study on the Security Implications of Information Leakages in Container Clouds. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 18, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.G.; Taheri, J.; Al-Dulaimy, A.; Kassler, A. PerfSim: A Performance Simulator for Cloud Native Microservice Chains. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2023, 11, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Dubey, K.; Pandey, R. Evolution of Emerging Computing paradigm Cloud to Fog: Applications, Limitations and Research Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence), Noida, India, 28–29 January 2021; pp. 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Arouk, O.; Nikaein, N. Kube5G: A Cloud-Native 5G Service Platform. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020—2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–11 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bardas, A.; Sundaramurthy, S.C.; Ou, X.; Deloach, S. MTD CBITS: Moving Target Defense for Cloud-Based IT Systems. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Oslo, Norway, 1–3 December 2017; pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nife, F.N.; Kotulski, Z. Application-Aware Firewall Mechanism for Software Defined Networks. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2020, 28, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, T.; Zhan, X.; Ma, X. {FOAP}:{Fine-Grained}{Open-World} android app fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 1579–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, T.; Lan, G.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, W. Eavesdropping mobile app activity via {Radio-Frequency} energy harvesting. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023; pp. 3511–3528. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.; Morvan, F.; Martinez-Gil, J.; Hameurlain, A. MTD-DS: An SLA-Aware Decision Support Benchmark for Multi-Tenant Parallel DBMSs. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 2743–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi, W.; Gur, G.; Stiller, B. Moving Target Defense (MTD) for 6G Edge-to-Cloud Continuum: A Cognitive Perspective. IEEE Netw. 2025, 39, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, R.; Tsankov, P.; Lenders, V.; Vanbever, L.; Vechev, M. NetHide: Secure and practical network topology obfuscation. In Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 693–709. [Google Scholar]

- Tunde-onadele, O.; Lin, Y.; Gu, X.; He, J.; Latapie, H. Self-Supervised Machine Learning Framework for Online Container Security Attack Detection. Acm Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. 2024, 19, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kong, F.; Deng, D.; Tang, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, C.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Ai, B.; Han, Z.; et al. Moving Target Defense Meets Artificial-Intelligence-Driven Network: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 13384–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Brito, C.; Fe, I.; Carvalho, J.; Torquato, M.; Choi, E.; Min, D.; Lee, J.-W.; Nguyen, T.A.; Silva, F.A. Event-Based Moving Target Defense in Cloud Computing With VM Migration: A Performance Modeling Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 165539–165554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.E.; Crouse, M.; Fulp, E.W.; Berenhaut, K.S. Analysis of network address shuffling as a moving target defense. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–14 June 2014; pp. 701–706. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Li, Z.; Zou, D.; Yuan, B. DSEOM: A Framework for Dynamic Security Evaluation and Optimization of MTD in Container-Based Cloud. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 18, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. An Optimal Active Defensive Security Framework for the Container-Based Cloud with Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, T.; Mallari, R.A. Technical Aspects of Cyber Kill Chain. In International Symposium on Security in Computing and Communication; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, C. Elastic Scheduling for Microservice Applications in Clouds. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2021, 32, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdun, U.; Queval, P.-J.; Simhandl, G.; Scandariato, R.; Chakravarty, S.; Jelic, M.; Jovanovic, A. Microservice Security Metrics for Secure Communication, Identity Management, and Observability. Acm Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2023, 32, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Sun, P.; Wang, Y.; Huo, S. An optimal defensive deception framework for the container-based cloud with deep reinforcement learning. Iet Inf. Secur. 2022, 16, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdun, U.; Queval, P.-J.; Simhandl, G.; Scandariato, R.; Chakravarty, S.; Jelic, M.; Jovanovic, A. Detection Strategies for Microservice Security Tactics. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casola, V.; De Benedictis, A.; Mazzocca, C.; Montanari, R. Designing Secure and Resilient Cyber-Physical Systems: A Model-Based Moving Target Defense Approach. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2024, 12, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Fan, G.; Zhang, J. Cost-Efficient Fault-Tolerant Workflow Scheduling for Deadline-Constrained Microservice-Based Applications in Clouds. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 20, 3220–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xia, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Xue, Z. SEAF: A Scalable, Efficient, and Application-independent Framework for container security detection. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2022, 71, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, E.; Iannucci, S. The state-of-the-art in container technologies: Application, orchestration and security. Concurr. Comput.-Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, V.S.D.; Sethuraman, S.C.; Khan, M.K. Container security: Precaution levels, mitigation strategies, and research perspectives. Comput. Secur. 2023, 135, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Ahmad, I.; Dimitriou, T. Container Security: Issues, Challenge and the Road Ahead. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 52976–52996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Sun, P.; Cheng, G.; Hu, H. Deep reinforcement learning based moving target defense strategy optimization scheme for cloud native environment. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2022, 44, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, F.; Huang, C.-T.; Zou, X. A moving-target defense strategy for cloud-based services with heterogeneous and dynamic attack surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–14 June 2014; pp. 804–809. [Google Scholar]

- Iraqi, O.; Bakkali, H.E. Immunizer: A Scalable Loosely-Coupled Self-Protecting Software Framework using Adaptive Microagents and Parallelized Microservices. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 29th International Conference on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WETICE), Bayonne, France, 10–13 September 2020; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Akamai. Akamai’s 2014 Online Holiday Shopping Trends and Traffic Report. 2023. Available online: https://content.akamai.com/PG2112-Holiday-Recap-Report.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Microservices attack the graph model | |

| Set of microservices | |

| Set of edges representing dependency relationships | |

| Set of microservice replica quantities | |

| Set of microservice cleaning cycles | |

| Set of microservice request arrival rates | |

| Dependency relationship between microservice and | |

| Difficulty of exploiting vulnerabilities in microservices | |

| Attack success rate of the microservice | |

| Weight between microservice and | |

| Security performance of the microservice system | |

| The number of available replicas of microservice | |

| Probability that replicas are in the cleaning state | |

| Probability that no replicas are in the cleaning state | |

| Service rate of each microservice replica | |

| User Quality of Service | |

| Defense effectiveness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Hu, H. An Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy for Microservices Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2025, 14, 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204096

Li Y, Li Y, Wang G, Hu H. An Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy for Microservices Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics. 2025; 14(20):4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204096

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuanbo, Yuanmou Li, Guoqiang Wang, and Hongchao Hu. 2025. "An Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy for Microservices Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning" Electronics 14, no. 20: 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204096

APA StyleLi, Y., Li, Y., Wang, G., & Hu, H. (2025). An Adaptive Dynamic Defense Strategy for Microservices Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics, 14(20), 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204096