DirectFS: An RDMA-Accelerated Distributed File System with CPU-Oblivious Metadata Indexing

Abstract

1. Introduction

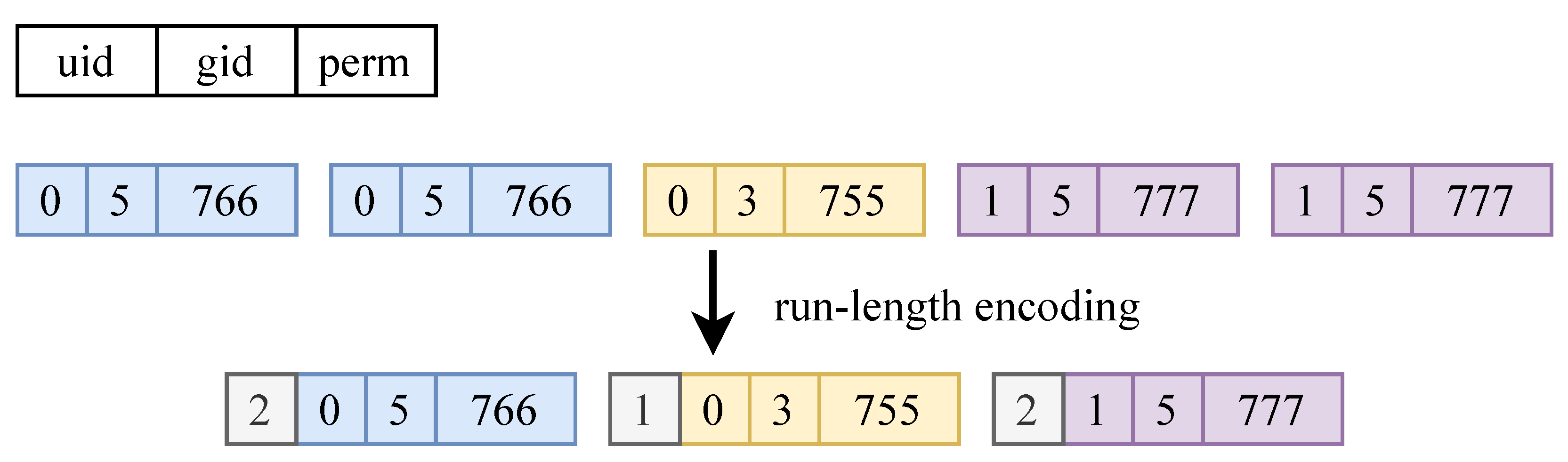

2. Background and Motivation

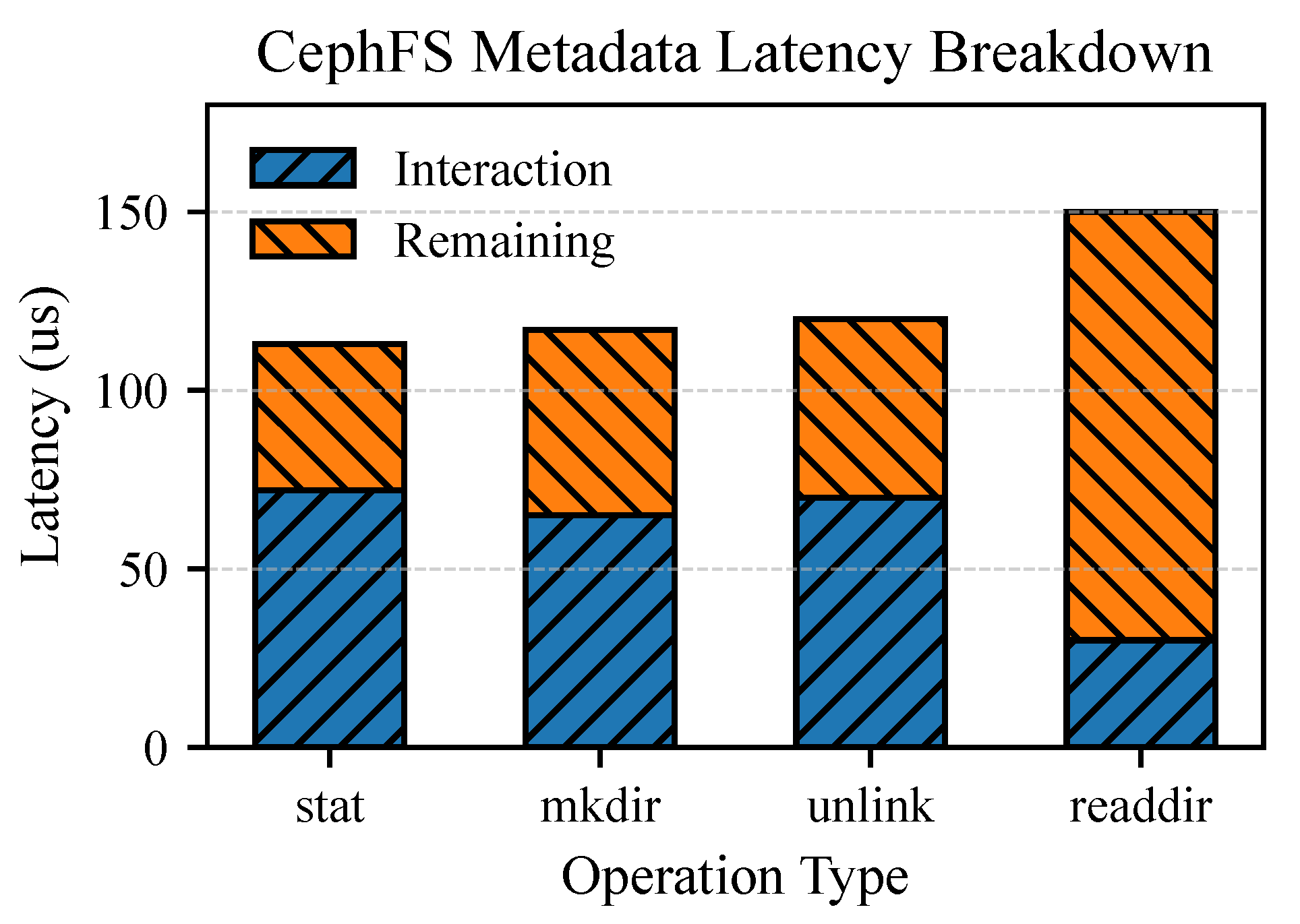

2.1. Metadata Management in Distributed File Systems

2.2. RDMA

2.3. RDMA-Enabled Distributed File Systems

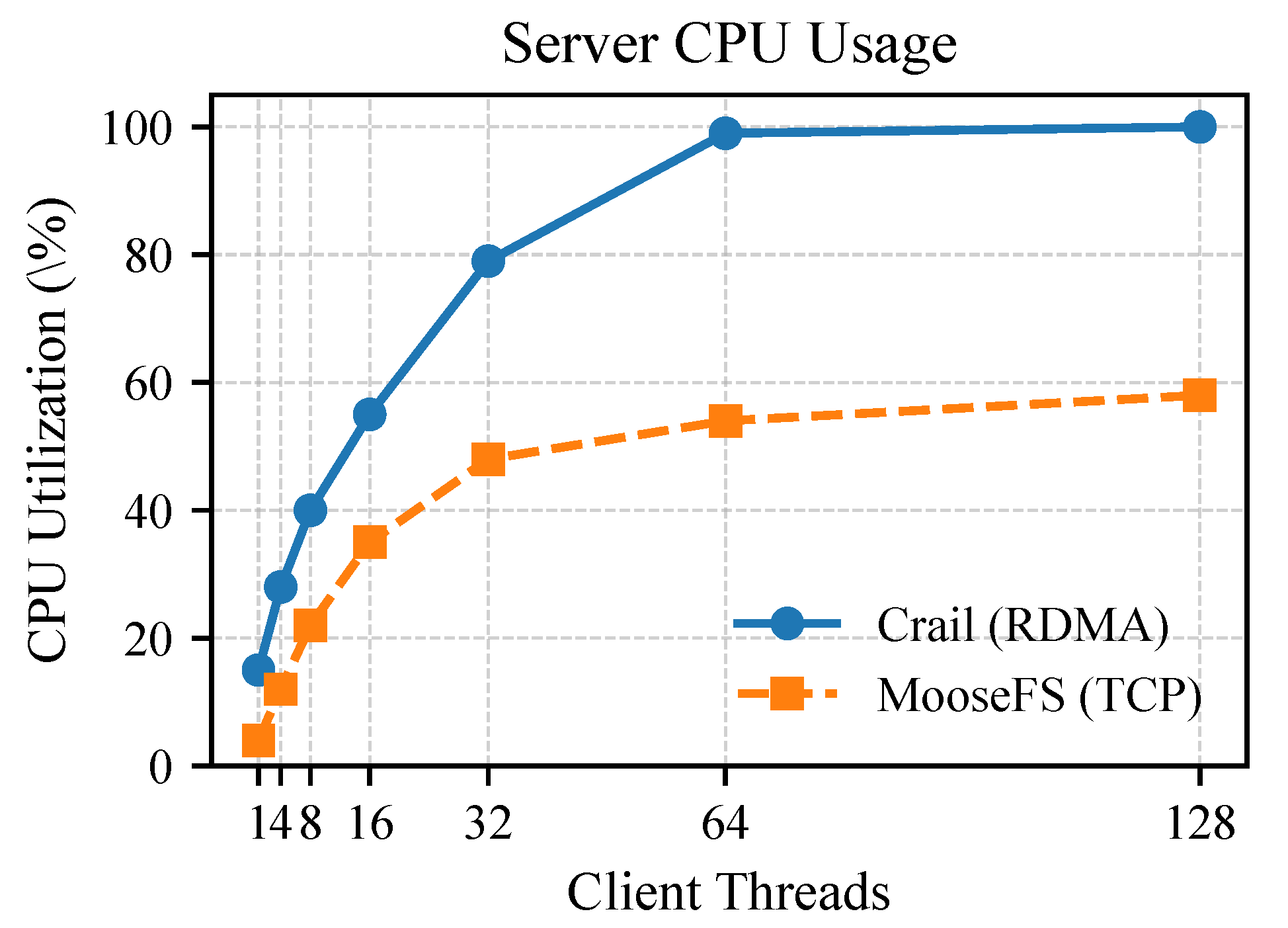

2.4. Limitations of Prior Art

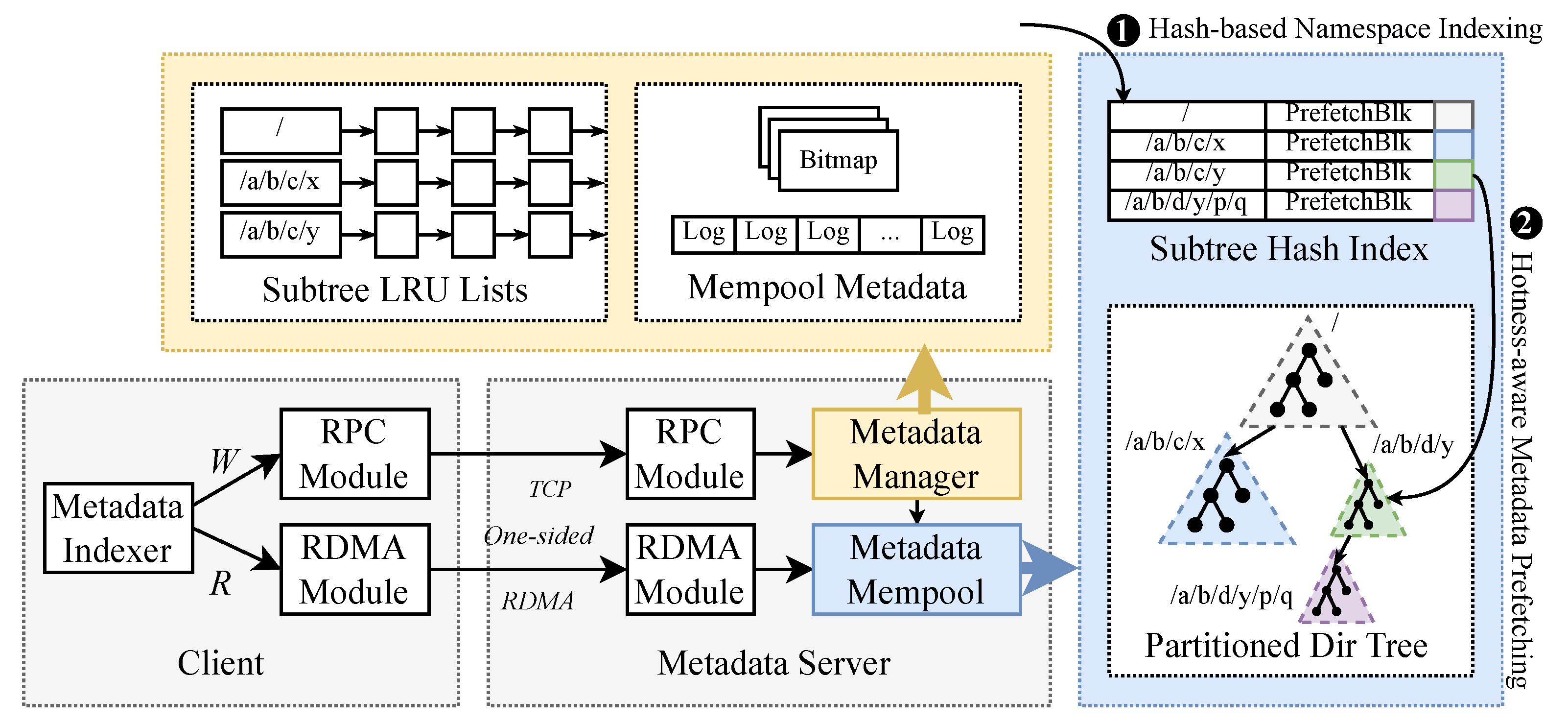

3. Design

3.1. Overview

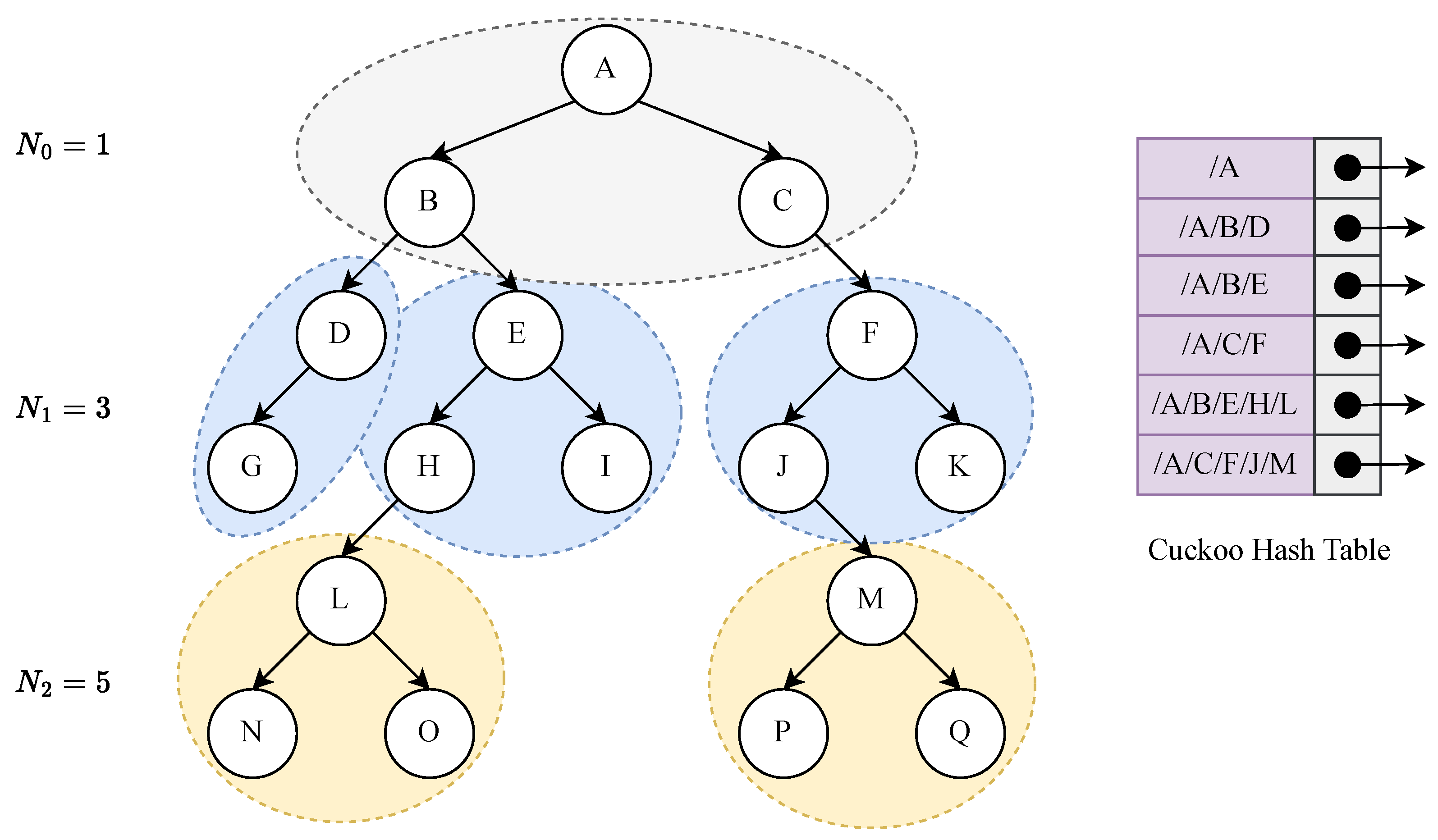

3.2. Hash-Based Namespace Indexing

| Algorithm 1: Speculative Pathname Resolution. |

|

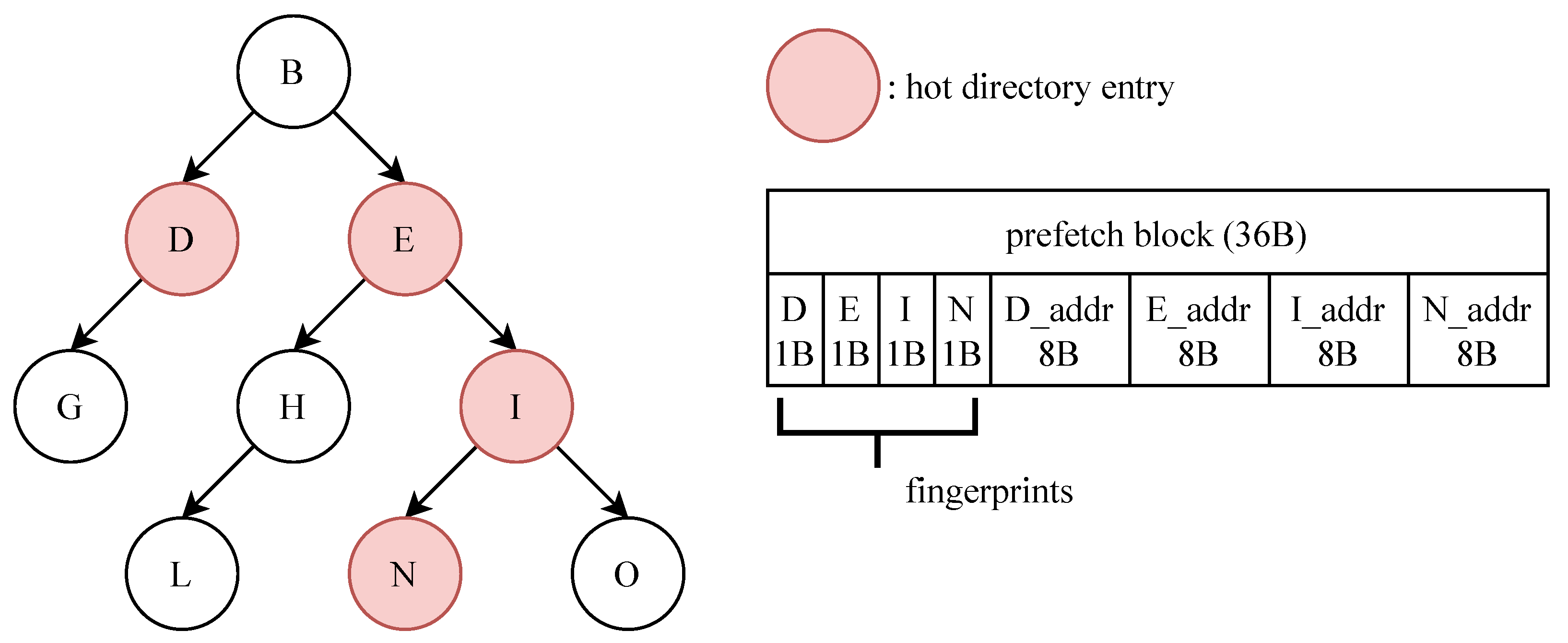

3.3. Hotness-Aware Metadata Prefetching

4. Implementation

5. Evaluation

- MooseFS [27]: The baseline distributed file system where clients communicate with the metadata server via TCP. The server performs metadata operations in DRAM and returns results over the network.

- Crail [24]: An RDMA-optimized user-space distributed file system that uses the DaRPC communication library for metadata access. Crail interacts with the file system via crail-fuse, a FUSE-based client implementation.

- DirectFS-Naive: A simplified variant of DirectFS that supports metadata access via one-sided RDMA but lacks full-path indexing and prefetching optimizations. Clients resolve pathnames by traversing the directory tree level by level and issuing one RDMA read per component.

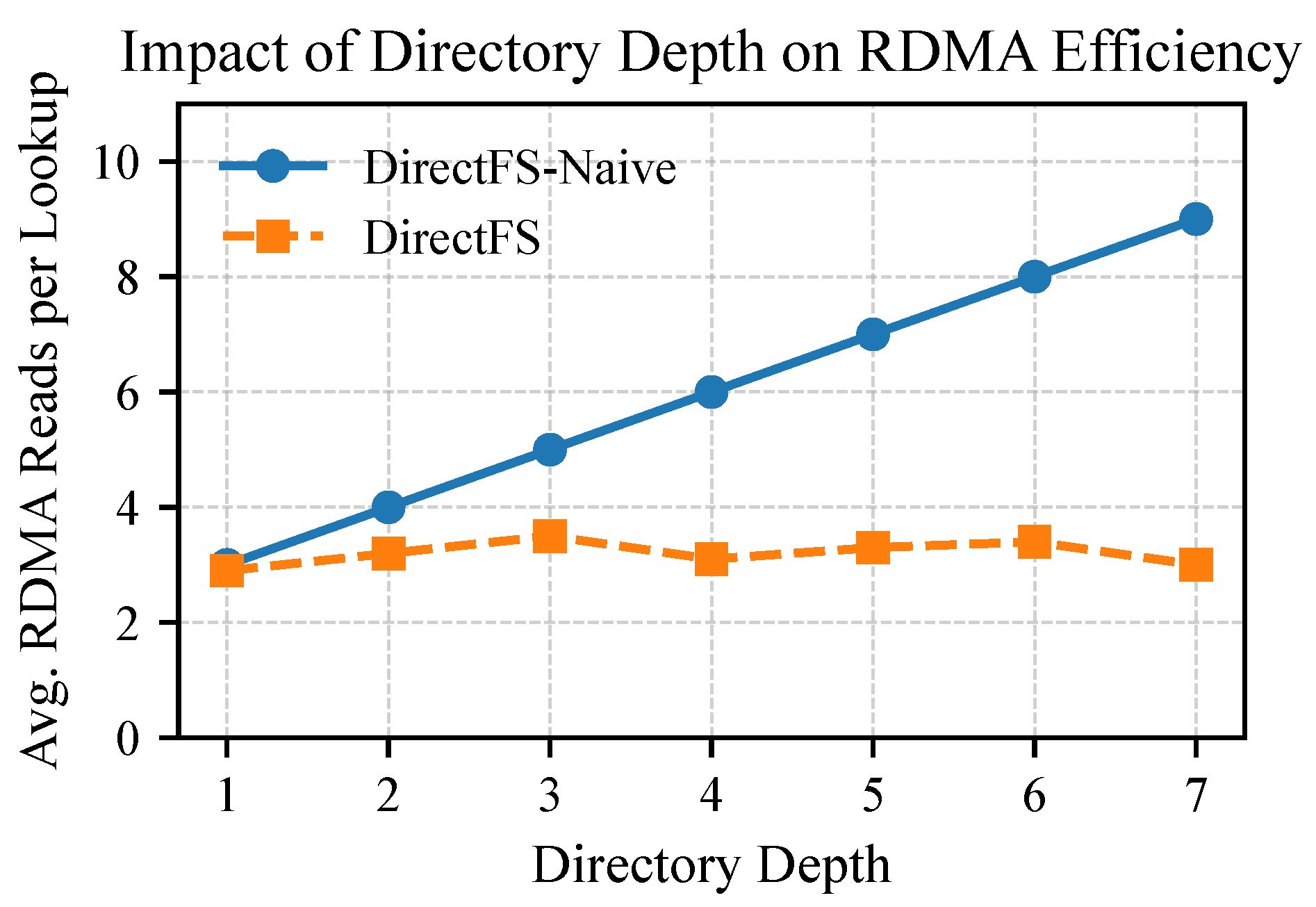

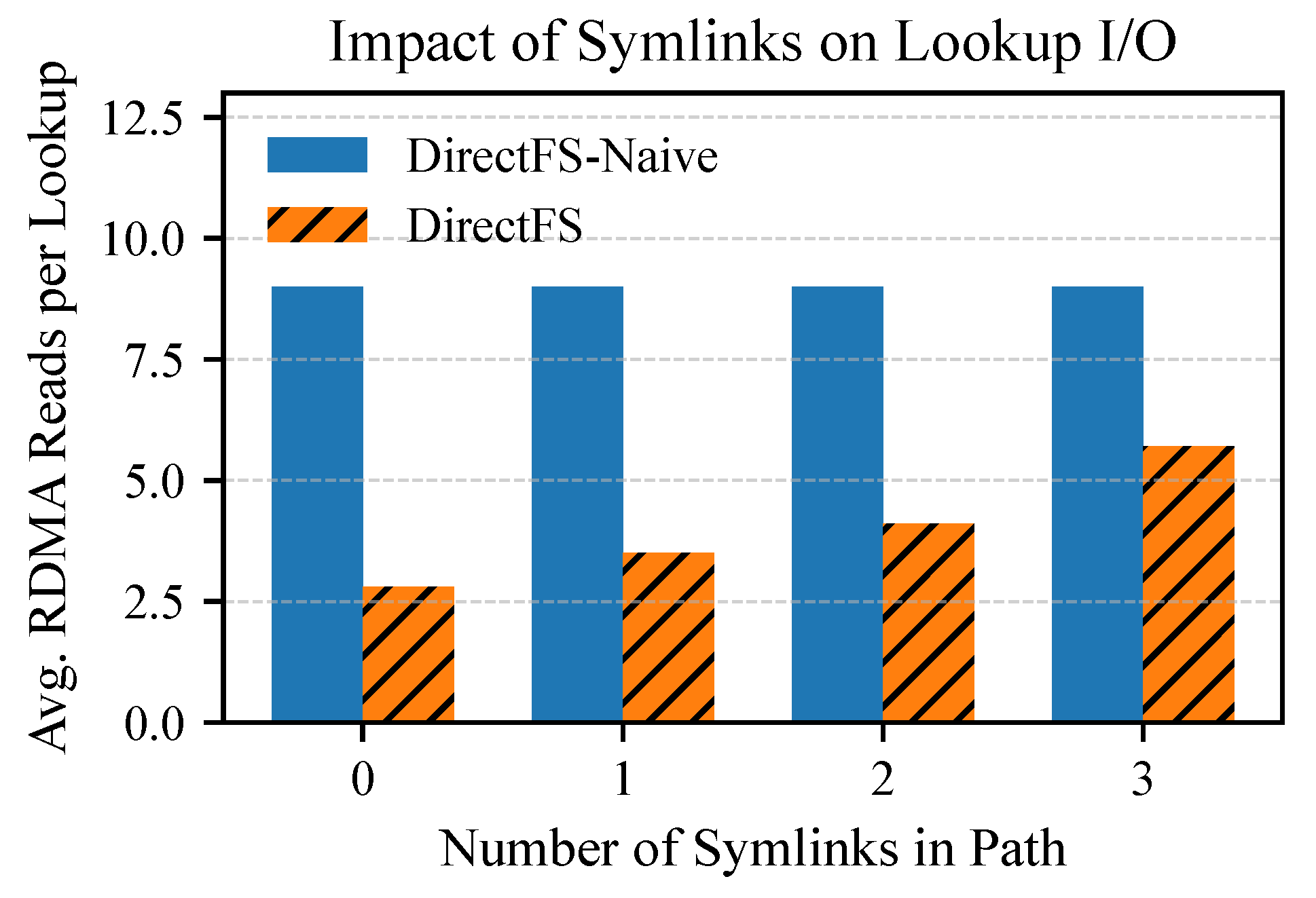

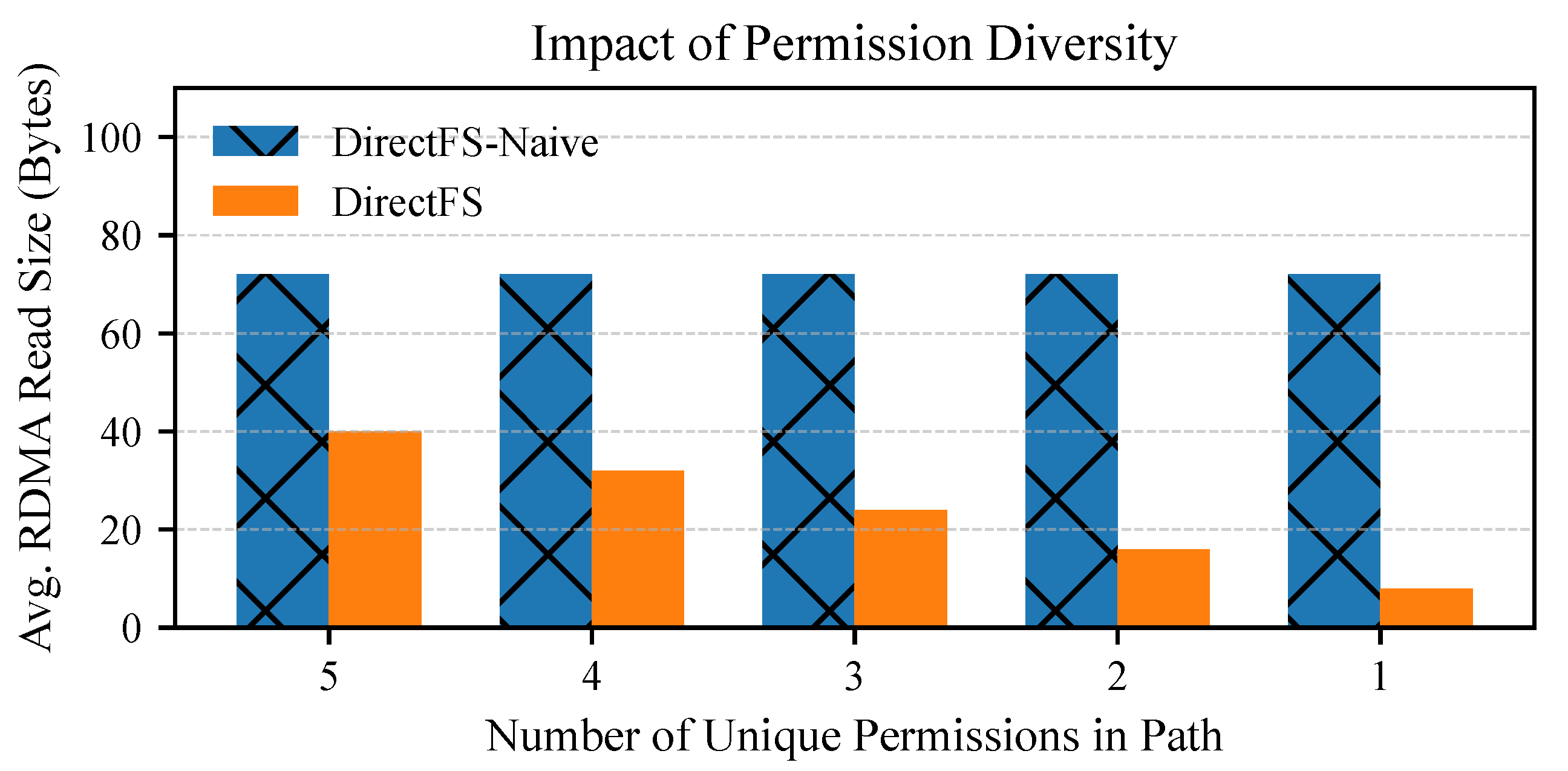

5.1. Evaluating Hash-Based Namespace Indexing

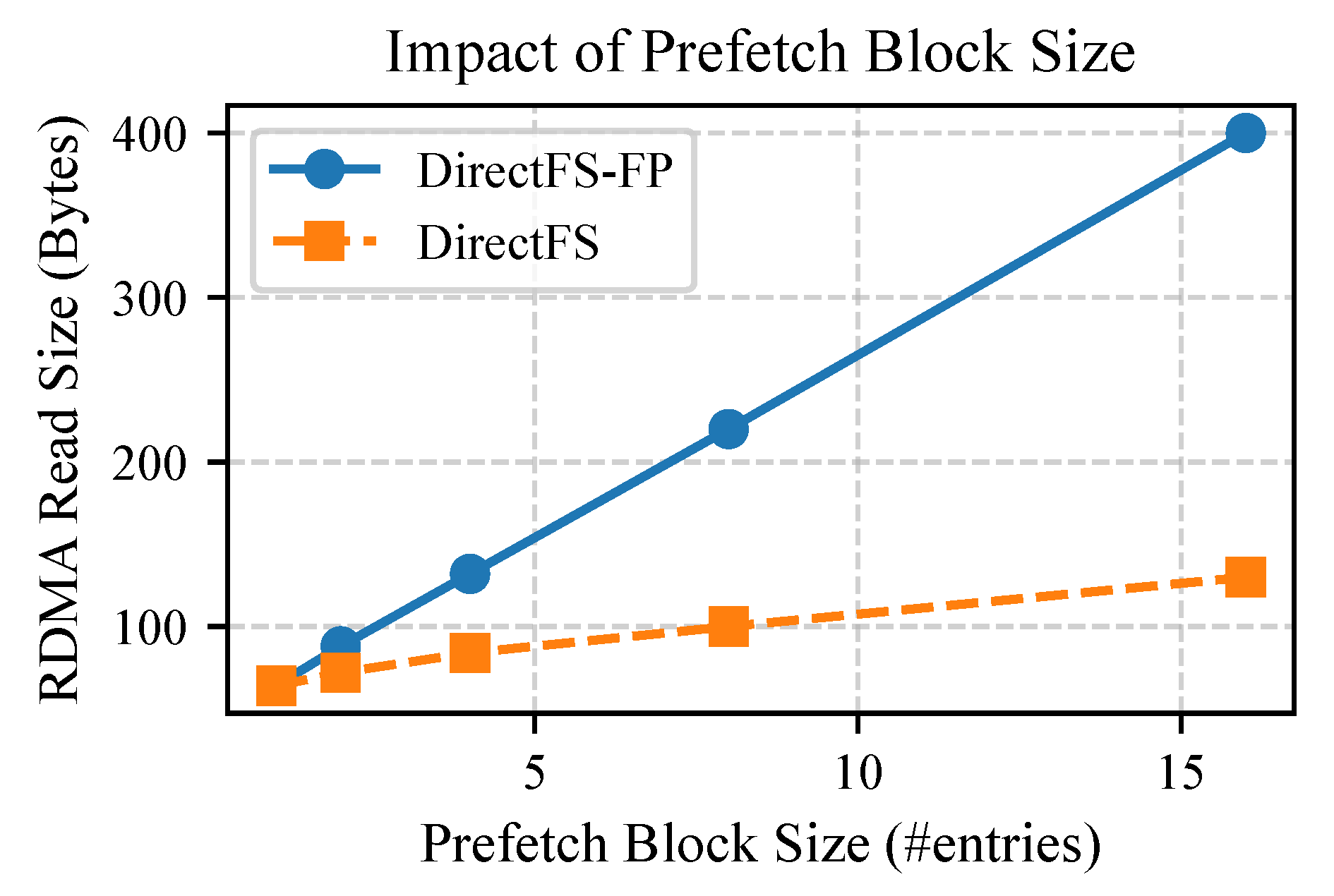

5.2. Evaluating Hotness-Aware Metadata Prefetching

- DirectFS-Naive: a baseline that performs RDMA-based per-component traversal without any indexing or prefetching;

- DirectFS-Hash: hash-based metadata indexing enabled, but prefetching disabled;

- DirectFS-FP: DirectFS with prefetching enabled, but without selective prefetching;

- DirectFS-SP: DirectFS with prefetching enabled, but without fused prefetching;

- DirectFS: full design with hash-based indexing, selective prefetching, and fused prefetching.

5.3. Filebench

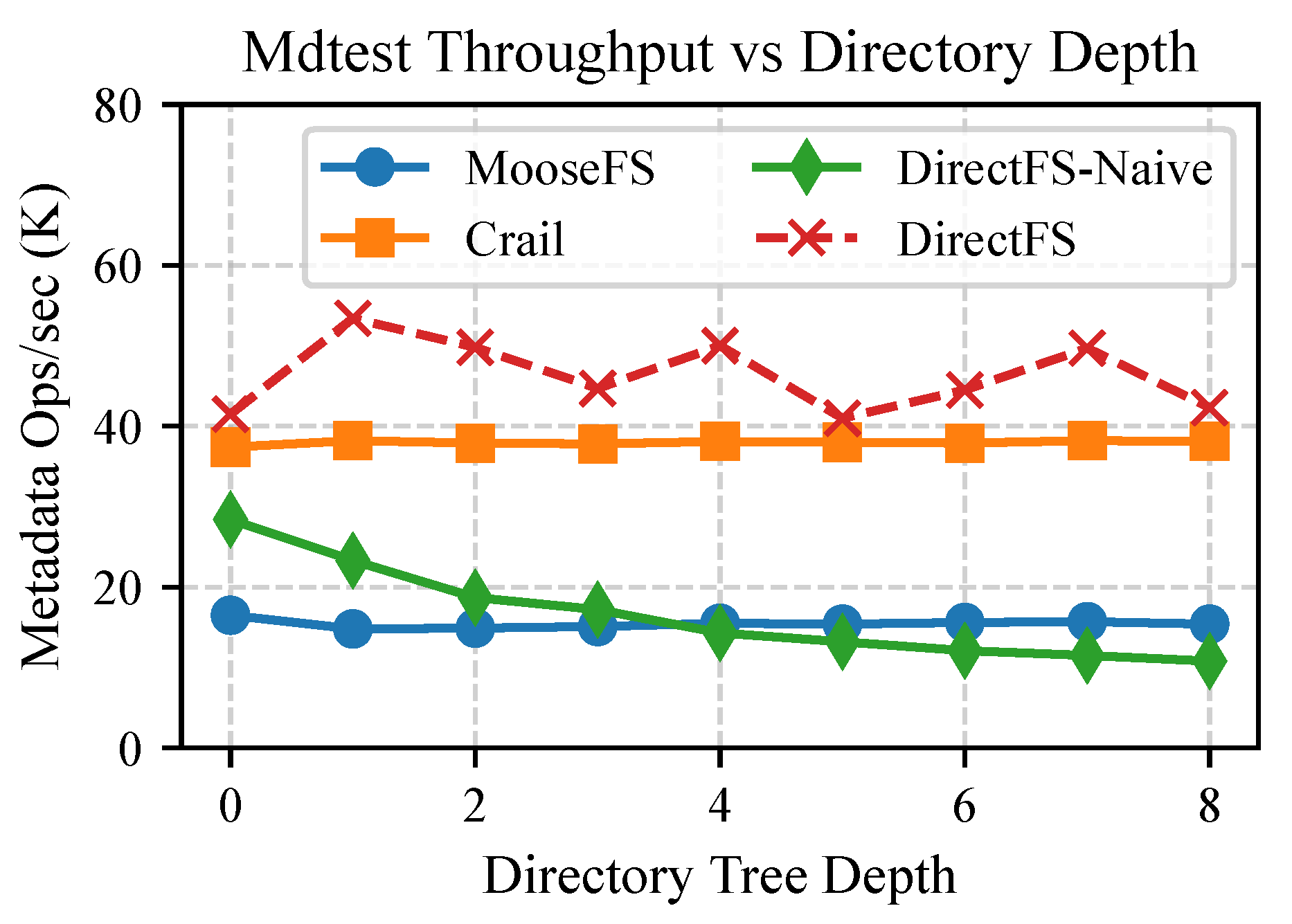

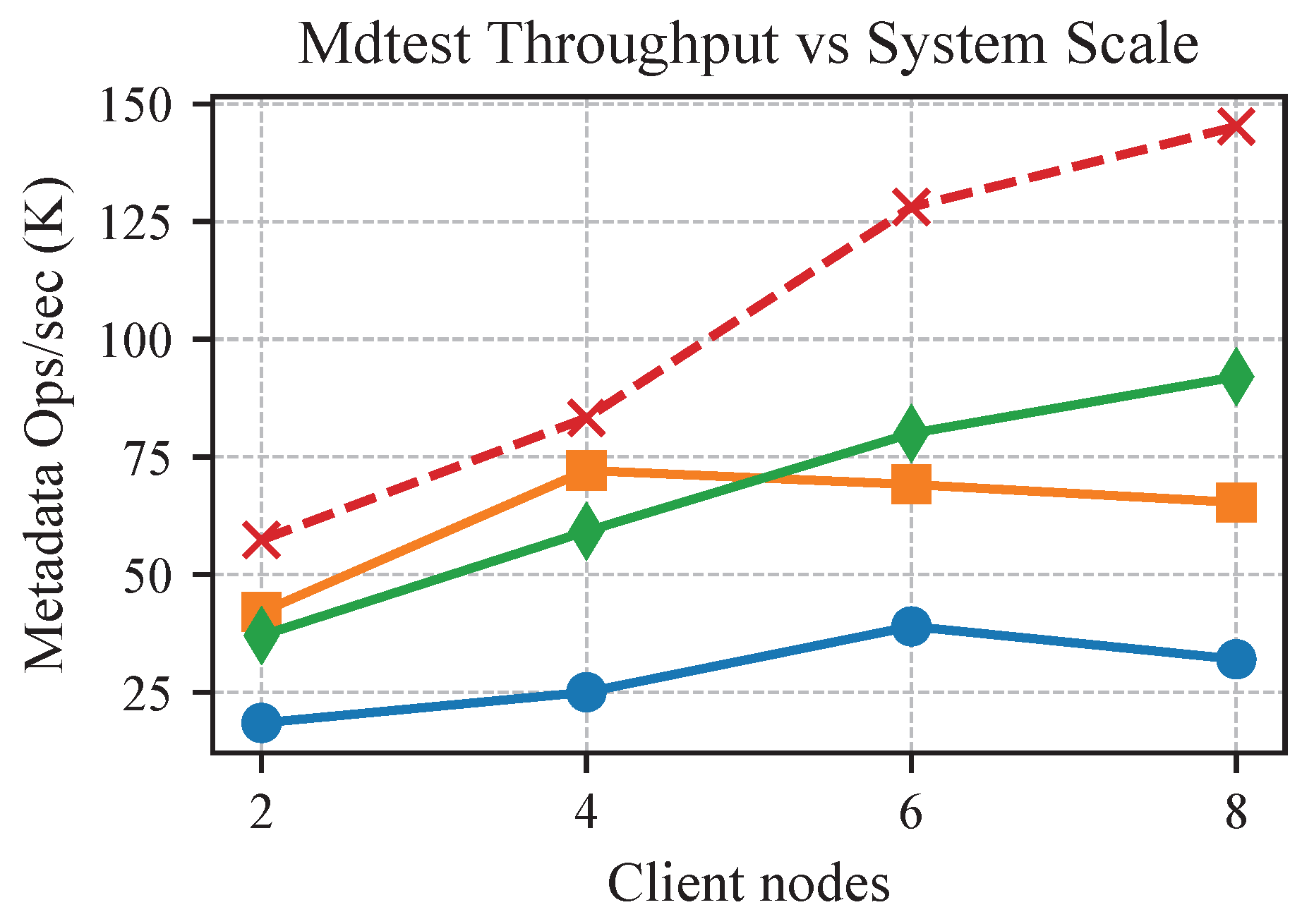

5.4. MDTest

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghemawat, S.; Gobioff, H.; Leung, S. The Google File System. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 19–22 October 2003; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shvachko, K.; Kuang, H.; Radia, S.; Chansler, R. The Hadoop Distributed File System. In Proceedings of the IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, S.A.; Brandt, S.A.; Miller, E.L.; Long, D.D.E.; Maltzahn, C. Ceph: A Scalable, High-Performance Distributed File System. In Proceedings of the 7th Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–8 November 2006; pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Carns, P.H.; Ligon, W.B., III; Ross, R.B.; Thakur, R. PVFS: A Parallel File System for Linux Clusters. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Linux Showcase & Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–14 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The Lustre File System. Available online: https://www.lustre.org/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Li, Q.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Wen, R.; Yao, W.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Huang, S.; Zhu, Z.; et al. More Than Capacity: Performance-oriented Evolution of Pangu in Alibaba. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 21–23 February 2023; pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, P.; Shu, J. InfiniFS: An Efficient Metadata Service for Large-Scale Distributed Filesystems. In Proceedings of the 20th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 22–24 February 2022; pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K.; Zheng, Q.; Patil, S.; Gibson, G.A. IndexFS: Scaling File System Metadata Performance with Stateless Caching and Bulk Insertion. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–21 November 2014; pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Gibson, G.A. Scale and Concurrency of GIGA+: File System Directories with Millions of Files. In Proceedings of the 9th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, San Jose, CA, USA, 15–17 February 2011; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A.; Abadi, D.J. CalvinFS: Consistent WAN Replication and Scalable Metadata Management for Distributed File Systems. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 16–19 February 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Niazi, S.; Ismail, M.; Haridi, S.; Dowling, J.; Grohsschmiedt, S.; Ronström, M. HopsFS: Scaling Hierarchical File System Metadata Using NewSQL Databases. In Proceedings of the 15th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2017; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Aghayev, A.; Weil, S.A.; Kuchnik, M.; Nelson, M.; Ganger, G.R.; Amvrosiadis, G. File Systems Unfit as Distributed Storage Backends: Lessons from 10 years of Ceph Evolution. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Huntsville, ON, Canada, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, N.S.; Wasi-ur-Rahman, M.; Lu, X.; Panda, D.K. High Performance Design for HDFS with Byte-Addressability of NVM and RDMA. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Supercomputing, Istanbul, Turkey, 1–3 June 2016; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Shu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Octopus: An RDMA-enabled Distributed Persistent Memory File System. In Proceedings of the 2017 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 12–14 July 2017; pp. 773–785. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.E.; Canini, M.; Kim, J.; Kostic, D.; Kwon, Y.; Peter, S.; Reda, W.; Schuh, H.N.; Witchel, E. Assise: Performance and Availability via Client-local NVM in a Distributed File System. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, Virtual Event, 4–6 November 2020; pp. 1011–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Lu, Y.; Lv, W.; Liao, X.; Zeng, S.; Shu, J. SingularFS: A Billion-Scale Distributed File System Using a Single Metadata Server. In Proceedings of the 2023 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 July 2023; pp. 915–928. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Izraelevitz, J.; Swanson, S. Orion: A Distributed File System for Non-Volatile Main Memory and RDMA-Capable Networks. In Proceedings of the 17th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Boston, MA, USA, 25–28 February 2019; pp. 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Jang, I.; Reda, W.; Im, J.; Canini, M.; Kostic, D.; Kwon, Y.; Peter, S.; Witchel, E. LineFS: Efficient SmartNIC Offload of a Distributed File System with Pipeline Parallelism. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 28th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Virtual Event, 26–29 October 2021; pp. 756–771. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Xie, X.; Chen, R.; Chen, H.; Zang, B. Characterizing and Optimizing Remote Persistent Memory with RDMA and NVM. In Proceedings of the 2021 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, Virtual Event, 14–16 July 2021; pp. 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, A.; Kaminsky, M.; Andersen, D. Datacenter RPCs can be General and Fast. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 19), Boston, MA, USA, 26–28 February 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stuedi, P.; Trivedi, A.; Metzler, B.; Pfefferle, J. DaRPC: Data Center RPC. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, Seattle, WA, USA, 3–5 November 2014; SOCC ’14. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, S.A.; Pollack, K.T.; Brandt, S.A.; Miller, E.L. Dynamic Metadata Management for Petabyte-Scale File Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE Conference on High Performance Networking and Computing, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 6–12 November 2004; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, A.; Kaminsky, M.; Andersen, D.G. Design Guidelines for High Performance RDMA Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 22–24 June 2016; pp. 437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Stuedi, P.; Trivedi, A.; Pfefferle, J.; Stoica, R.; Metzler, B.; Ioannou, N.; Koltsidas, I. Crail: A High-Performance I/O Architecture for Distributed Data Processing. In Bulletin of the IEEE Computer Society Technical Committee on Data Engineering; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:19264551 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Salomon, E.C. Accelio: IO, Message and RPC Acceleration Library. Available online: https://github.com/accelio/accelio (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Boyer, E.B.; Broomfield, M.C.; Perrotti, T.A. GlusterFS One Storage Server to Rule Them All; Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL): Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszona-Zawadzki, J.; Saglabs, S.A. Moose File System (MooseFS). Available online: https://moosefs.com (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Dong, M.; Bu, H.; Yi, J.; Dong, B.; Chen, H. Performance and Protection in the ZoFS User-space NVM File System. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Huntsville, ON, Canada, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 478–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Hao, X.; Wang, T.; Lo, E. Dash: Scalable hashing on persistent memory. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2020, 13, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukid, I.; Lasperas, J.; Nica, A.; Willhalm, T.; Lehner, W. FPTree: A Hybrid SCM-DRAM Persistent and Concurrent B-Tree for Storage Class Memory. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Management of Data, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; SIGMOD ’16. pp. 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zuo, P.; Shen, J.; Gu, J.; Wang, X.; Lyu, M.R.; Zhou, Y. SMART: A High-Performance Adaptive Radix Tree for Disaggregated Memory. In Proceedings of the 17th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 23), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 July 2023; pp. 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- NVIDIA Developer Documentation. User-Mode Memory Registration (UMR); NVIDIA Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Tang, L.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, P.; Peng, W.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Yan, L.; et al. When Cloud Storage Meets RDMA. In Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 21), Virtual Event, 12–14 April 2021; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 519–533. [Google Scholar]

- Filebench. Available online: https://github.com/filebench/filebench (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- MDTest. Available online: https://github.com/LLNL/mdtest (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- dmp265. Crail-Fuse: FUSE Interface for Crail Distributed File System; GitHub Repository: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC). SPECsfs2008 User’s Guide; Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC): Warrenton, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Depth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive RDMA (μs) | 24 | 31 | 37 | 47 | 58 | 66 | 76 |

| RPC (μs) | 63 | 64 | 65 | 61 | 61 | 63 | 62 |

| FS | Create | Unlink | Mkdir | Rmdir | Chmod | Rename |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MooseFS | 214 | 197 | 202 | 195 | 181 | 230 |

| DirectFS | 217 | 201 | 205 | 202 | 195 | 251 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, R.; Cai, M. DirectFS: An RDMA-Accelerated Distributed File System with CPU-Oblivious Metadata Indexing. Electronics 2025, 14, 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193778

Jiang L, Zhang Z, Ni R, Cai M. DirectFS: An RDMA-Accelerated Distributed File System with CPU-Oblivious Metadata Indexing. Electronics. 2025; 14(19):3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193778

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Lingjun, Zhaoyao Zhang, Ruixuan Ni, and Miao Cai. 2025. "DirectFS: An RDMA-Accelerated Distributed File System with CPU-Oblivious Metadata Indexing" Electronics 14, no. 19: 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193778

APA StyleJiang, L., Zhang, Z., Ni, R., & Cai, M. (2025). DirectFS: An RDMA-Accelerated Distributed File System with CPU-Oblivious Metadata Indexing. Electronics, 14(19), 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193778