Heuristic-Based Computing-Aware Routing for Dynamic Networks

Abstract

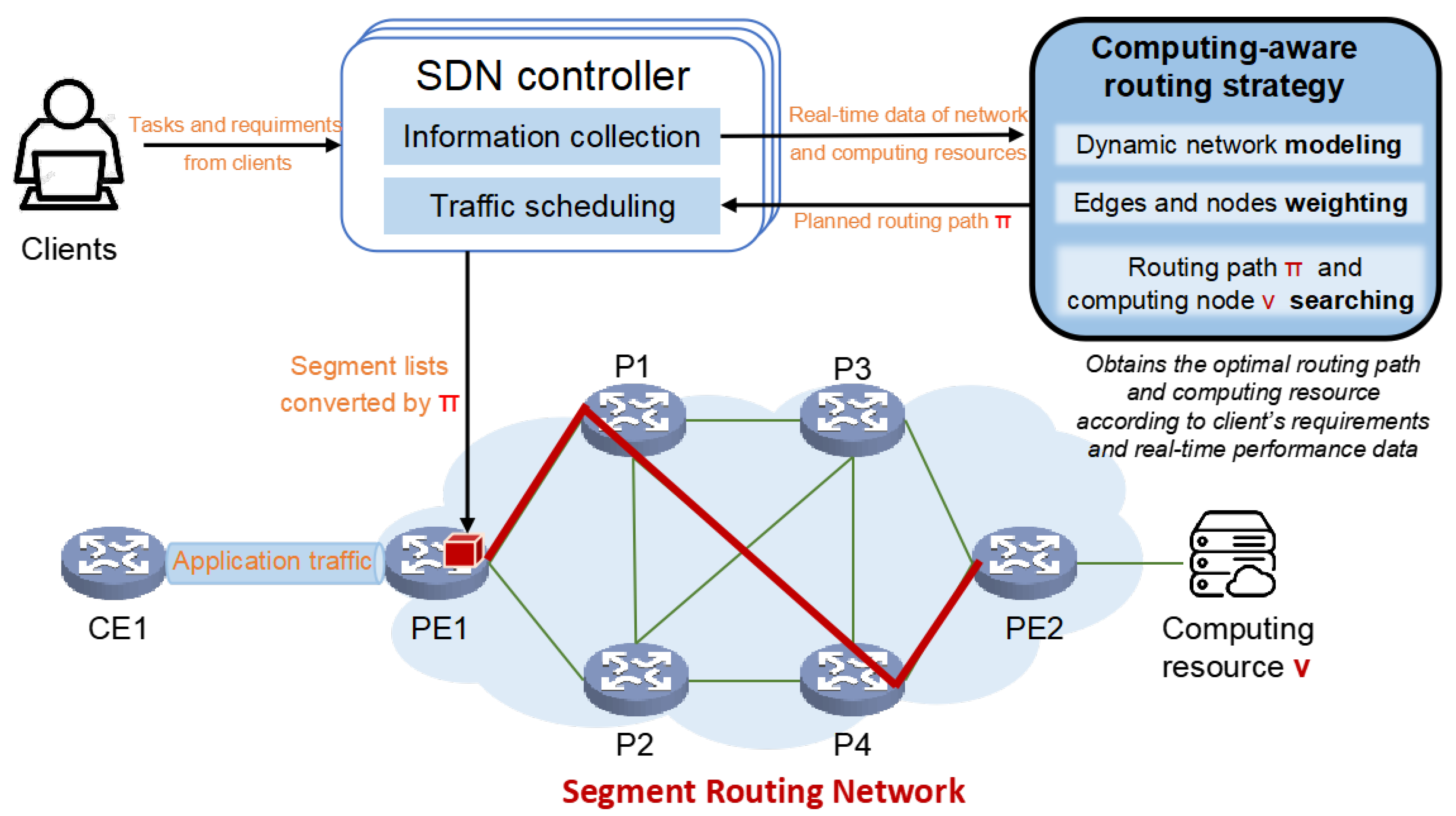

1. Introduction

- A study on computing-aware routing for the dynamic CPN environment, which considers seven-dimensional QoS attributes of the network resource and the computing resource. These attributes are transformed into two-dimensional comprehensive attribute priorities, enabling a holistic optimization of the computation and transmission processes.

- The proposal of a novel landmark-based A-star algorithm to solve the computing-aware routing problem in the dynamic network environment. This algorithm first transforms the computing-aware routing problem into a single-source shortest path problem and solves it under QoS constraints.

- Extensive experiments on both scalable simulation networks and a real dedicated network in Zhejiang province. The results demonstrate that the proposed heuristic-based computing-aware routing algorithm improves routing accuracy compared to traditional shortest path routing. It also reduces the path planning time by over 40 times while maintaining routing accuracy.

2. Related Work

3. Dynamic Network and Computing Resource Modeling

3.1. Definition of Dynamic Network Model

3.2. Time-Varying Network and Computing Resource Modeling

3.3. Basic KPIs for Weight Set Mapping

4. Problem Formulation

4.1. Shortest Path Problem

4.2. Computing-Aware Network Routing Problem

| Algorithm 1 Heuristic-based computing-aware routing (H-CAR) algorithm |

Require: The snapshot of the dynamic network model , including the node set V, edge set E, impact factor set of nodes , impact factor set of edges , and the shortest path matrix between nodes P Require: Task ’s parameter set Ensure: The optimal computing-aware routing path and the overall cost

|

| Algorithm 2 Landmark-based A-STAR{} |

|

5. Experiments and Evaluations

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.2. Simulation Experiments and Performance Evaluation

5.2.1. Accuracy of Path Routing Under Fluctuating Networks

5.2.2. Network Load Testing

5.3. Real-World Experiments and Case Study

5.3.1. Routing with Computing-Aware Information

5.3.2. Routing with Varying Network and Computing Resource Status

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, M.N.; Duong, V.B.; Kim, Y. Design of Computing-Aware Traffic Steering Architecture for 5G Mobile User Plane. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88370–88382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Edge computing: Vision and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Duan, X.; Fu, Y. A computing-aware routing protocol for Computing Force Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Service Science (ICSS), Zhuhai, China, 13–15 May 2022; pp. 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz, D.; Ramos, F.M.; Verissimo, P.E.; Rothenberg, C.E.; Azodolmolky, S.; Uhlig, S. Software-defined networking: A comprehensive survey. Proc. IEEE 2014, 103, 14–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, B.; Al-Dubai, A.Y.; Ekonomou, E.; Alsarhan, A.; Nasser, Y.; Mackenzie, L.M.; Boukerche, A. A survey of limitations and enhancements of the ipv6 routing protocol for low-power and lossy networks: A focus on core operations. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 21, 1607–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Mobile Communications Co., Ltd.; Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. White Paper of Computing-Aware Networking; Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): Fremont, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, P.C. Hotspot mitigation for mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2018, 7, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalwash, H.; Huang, C.H. A QoS framework for SDN-based networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th International Conference on Collaboration and Internet Computing (CIC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 18–20 October 2018; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W. Data-driven QoS and QoE management in smart cities: A tutorial study. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quy, V.K.; Nam, V.H.; Linh, D.M.; Ban, N.T.; Han, N.D. A survey of QoS-aware routing protocols for the MANET-WSN convergence scenarios in IoT networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 120, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Kumar, D. A survey on QoS mechanisms in WSN for computational intelligence based routing protocols. Wirel. Netw. 2020, 26, 2465–2486. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Song, C.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C.; Yin, H. Economic Dispatch of an Integrated Microgrid Based on the Dynamic Process of CCGT Plant. In Proceedings of the 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Kunming, China, 22–24 May 2021; pp. 985–990. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaran, V.; Kumar, V.V.; Joseph, R.B.; Munirathanam, M.; Jeyakumar, B. Improving network security based on trust-aware routing protocols using long short-term memory-queuing segment-routing algorithms. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. (IJITPM) 2021, 12, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M.; Yang, Y. A survey of routing protocols for underwater wireless sensor networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Haseeb, K.; Almustafa, K.M.; Jan, Z.; Saba, T.; Tariq, U. Secure and energy-aware heuristic routing protocol for wireless sensor network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 163962–163974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amgoth, T.; Jana, P.K. Energy-aware routing algorithm for wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2015, 41, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Fortino, G.; Pace, P.; Aloi, G.; Li, W. Environment-fusion multipath routing protocol for wireless sensor networks. Inf. Fusion 2020, 53, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.T. Multipath cooperative routing with efficient acknowledgement for LEO satellite networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2018, 18, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Du, Z.; Boucadair, M.; Contreras, L.M.; Drake, J. A Framework for Computing-Aware Traffic Steering (CATS). In Draft-Ietf-Catsframework-02; Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): Fremont, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, F.; Lemmi, L.; Puliafito, C.; Virdis, A.; Mingozzi, E. A Computing-Aware Framework for Dynamic Traffic Steering in the Edge-Cloud Computing Continuum. In Proceedings of the 2025 34th International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN), Tokyo, Japan, 4–7 August 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Gu, S.; Zhuang, G.; Li, F. Dyncast: Use dynamic anycast to facilitate service semantics embedded in ip address. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 22nd International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing (HPSR), Paris, France, 7–10 June 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. Containers and cloud: From lxc to docker to kubernetes. IEEE Cloud Comput. 2014, 1, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokusashi, Y.; Dang, H.T.; Pedone, F.; Soulé, R.; Zilberman, N. The case for in-network computing on demand. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth EuroSys Conference 2019, Dresden, Germany, 25–28 March 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Yu, G.; Cai, Y.; He, Y. Latency optimization for resource allocation in mobile-edge computation offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2018, 17, 5506–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, V.D.; Corson, M.S. A highly adaptive distributed routing algorithm for mobile wireless networks. In Proceedings of the INFOCOM’97, Kobe, Japan, 7–11 April 1997; Volume 3, pp. 1405–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.K.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Vashishth, V.; Khanna, A.; Chhabra, A. RLProph: A dynamic programming based reinforcement learning approach for optimal routing in opportunistic IoT networks. Wirel. Netw. 2020, 26, 4319–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawbani, A.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Al-Dubai, A.; Min, G.; Busaileh, O. Novel architecture and heuristic algorithms for software-defined wireless sensor networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2020, 28, 2809–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouarafa, S.; Saadane, R.; Rahmani, M.D. Inspired from Ants colony: Smart routing algorithm of wireless sensor network. Information 2018, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasan, P.; Suárez-Varela, J.; Rusek, K.; Barlet-Ros, P.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A. Deep reinforcement learning meets graph neural networks: Exploring a routing optimization use case. Comput. Commun. 2022, 196, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, A.; Sun, X.; Moh, S.; Hung, P.C. Organized topology based routing protocol in incompletely predictable ad-hoc networks. Comput. Commun. 2017, 99, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhija, N.; Bautista, E. Towards a framework for monitoring and analyzing high performance computing environments using kubernetes and prometheus. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), Leicester, UK, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kocak, C.; Zaim, K. Performance measurement of IP networks using two-way active measurement protocol. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 17–18 May 2017; pp. 249–254. [Google Scholar]

| Collected Sample e | Delay De | Delay Variation DVe | Packet Loss Rate Le | Users Label d = <True, False> |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| … | … | … | … | … |

| n |

| Number of Tasks | Load Balancing | Shortest Path | H-CAR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Search Space | Avg. Time (ms) | Avg. Search Space | Avg. Time (ms) | Avg. Search Space | Avg. Time (ms) | |

| 10 | 16.39 | 21.5 | 21.85 | 23.58 | 4.15 | 16.97 |

| 50 | 16.31 | 22.52 | 23.04 | 23.81 | 4.18 | 20.95 |

| 100 | 17.01 | 25.39 | 23.61 | 28.21 | 4.30 | 26.12 |

| 200 | 16.57 | 52.82 | 24.33 | 78.88 | 4.33 | 38.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Z.; Wang, L.; Ning, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Jiang, J. Heuristic-Based Computing-Aware Routing for Dynamic Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14183724

Lin Z, Wang L, Ning W, Zhao Y, Yu L, Jiang J. Heuristic-Based Computing-Aware Routing for Dynamic Networks. Electronics. 2025; 14(18):3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14183724

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Zhiyi, Lingjie Wang, Wenxin Ning, Yuxiang Zhao, Li Yu, and Jian Jiang. 2025. "Heuristic-Based Computing-Aware Routing for Dynamic Networks" Electronics 14, no. 18: 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14183724

APA StyleLin, Z., Wang, L., Ning, W., Zhao, Y., Yu, L., & Jiang, J. (2025). Heuristic-Based Computing-Aware Routing for Dynamic Networks. Electronics, 14(18), 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14183724