Using Large Language Models to Infer Problematic Instagram Use from User Engagement Metrics: Agreement Across Models and Validation with Self-Reports

Abstract

1. Introduction

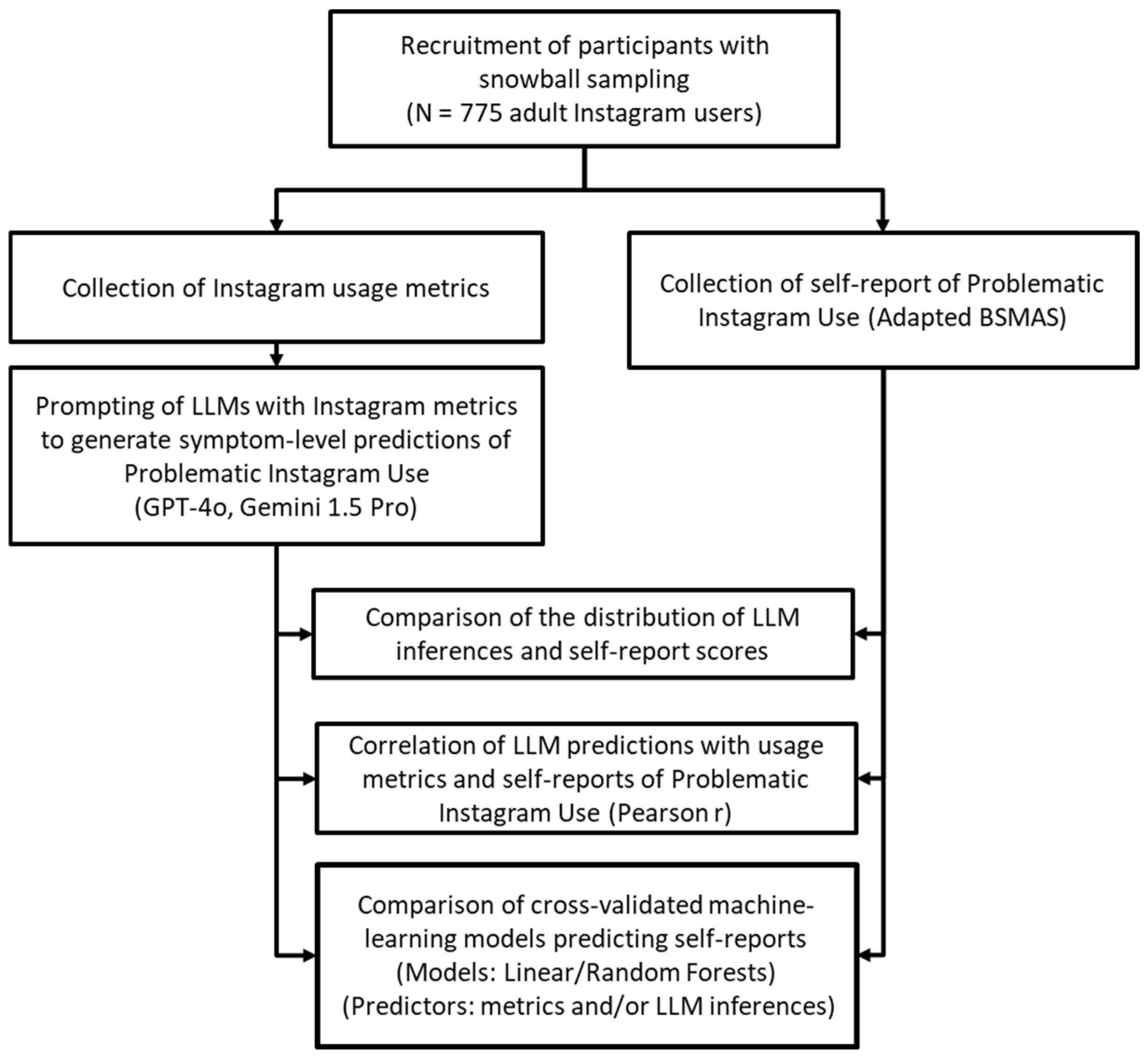

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Problematic Instagram Use

2.2.2. Instagram Usage Metrics

2.2.3. Leveraging Large Language Models for Inferring Problematic Instagram Use from Instagram Usage Metrics

“You are tasked with analyzing a dataset to infer a user’s potential level of Instagram addiction. The dataset includes information about the average number of last week’s published posts and stories, average daily time spent on the app, and current count of followers and following. Use this information to infer a symptom score on a 5-point scale (1 = Very rarely, 5 = Very often) for each of the six addiction dimensions:- Salience (Original Item: How often have you spent a lot of time thinking about or planned use of Instagram?)- Mood Modification (Original Item: How often have you used Instagram in order to forget about personal problems?)- Tolerance (Original Item: How often have you felt an urge to use Instagram more and more?)- Withdrawal (Original Item: How often have you become restless or troubled if you have been prohibited from using Instagram?)- Conflict (Original Item: How often have you used Instagram so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/study?)- Relapse (Original Item: How often have you tried to cut down on the use of Instagram without success?)USER DATA:- Weekly Posts: 0- Weekly Stories: 40- Time Spent on Instagram (average minutes/day): 165- Followers Count: 824- Following Count: 539Task: Generate the scores considering all input factors and output them in the specified format.Output Format:A comma-separated list of scores from 1 to 5 for each of the six symptoms.”

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

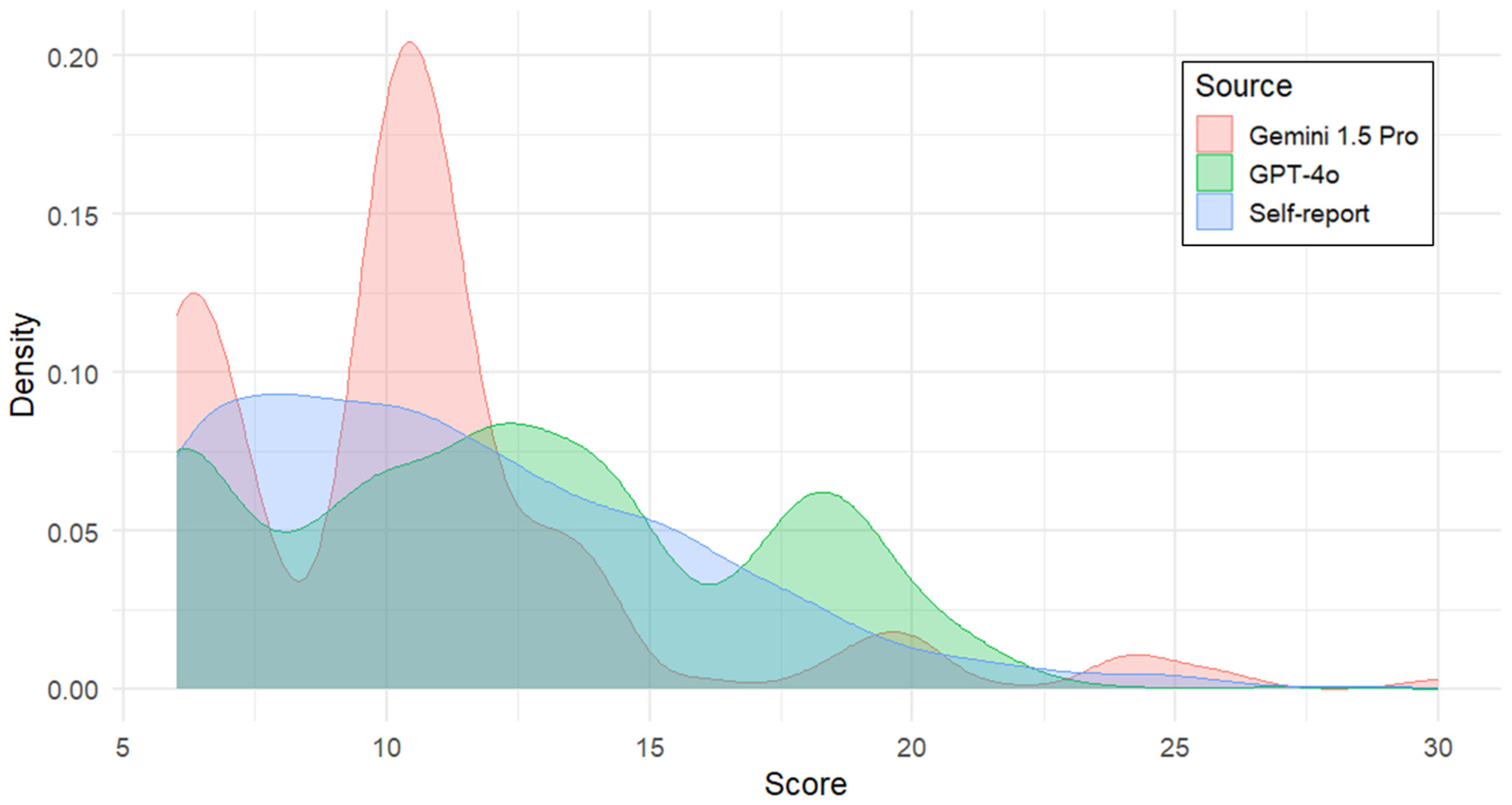

3.1. Distribution of LLM-Inferred and Self-Reported Scores for Problematic Instagram Use

3.2. Associations Between Instagram Usage Metrics and Self-Reported and Problematic Use Scores

3.3. Cross-Model Agreement in LLM-Inferred Scores for Problematic Instagram Use

3.4. Concurrent Validity Between LLM-Inferred and Self-Reported Scores of Problematic Instagram Use

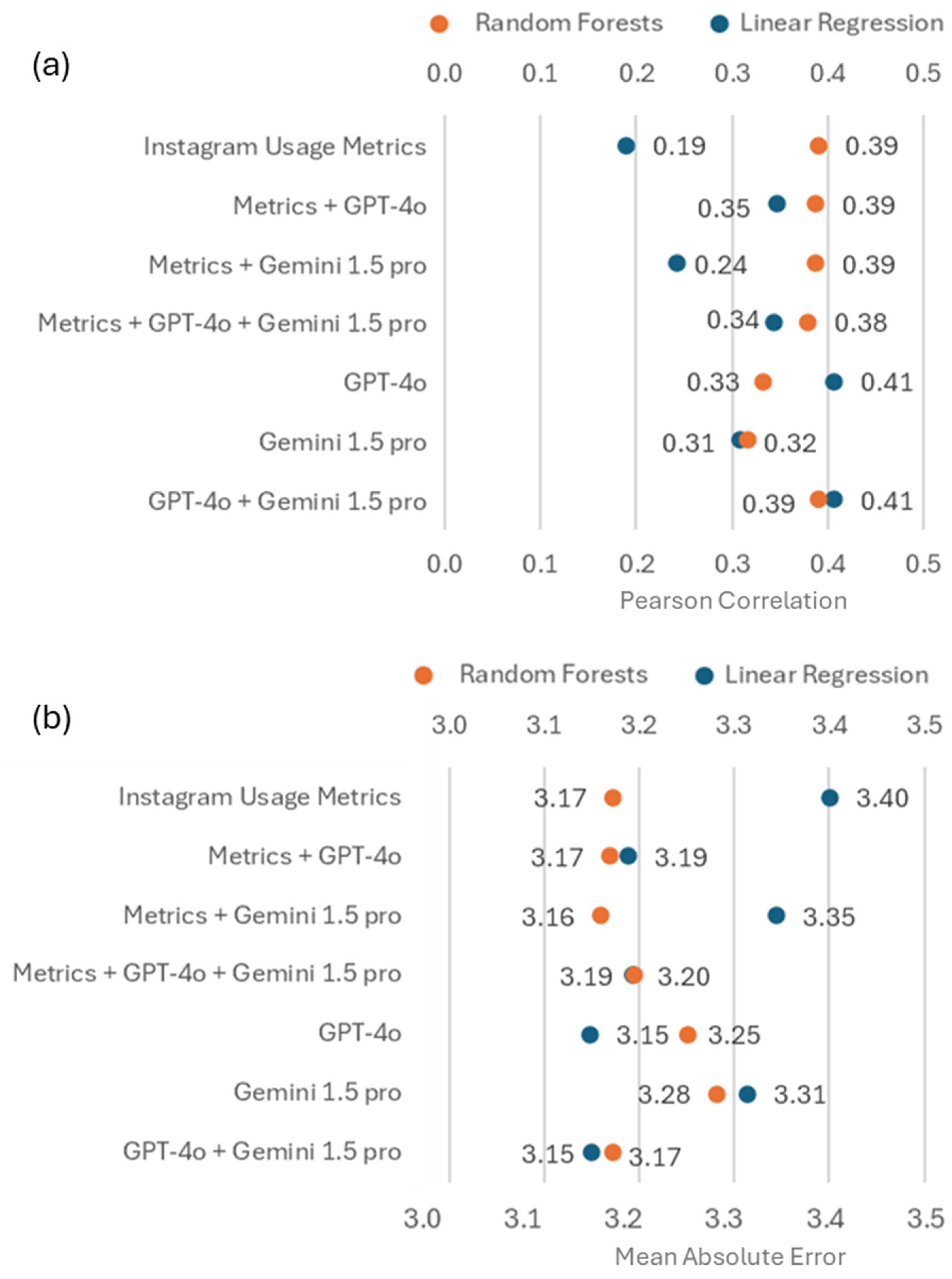

3.5. Incremental Validity of LLM Inferences over Instagram Usage Metrics in Predicting Self-Reported Problematic Instagram Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malgaroli, M.; Schultebraucks, K.; Myrick, K.J.; Loch, A.A.; Ospina-Pinillos, L.; Choudhury, T.; Kotov, R.; De Choudhury, M.; Torous, J. Large language models for the mental health community: Framework for translating code to care. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, e282–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkmer, S.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Schwarz, E. Large language models in psychiatry: Opportunities and challenges. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Zhang, R.F.; Shi, L.; Richie, R.; Liu, H.; Tseng, A.; Quan, W.; Ryan, N.D.; Brent, D.A.; Tsui, F. Classifying social determinants of health from unstructured electronic health records using deep learning-based natural language processing. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 127, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteiro, P.; Rijcken, E.; Zervanou, K.; Kaymak, U.; Scheepers, F.; Spruit, M. Machine learning for violence risk assessment using Dutch clinical notes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Tian, K.; Li, A.; Hartung, S.; Adithan, S.; Behzadi, F.; Calle, J.; Osayande, D.; Pohlen, M.; Rajpurkar, P. Multimodal image-text matching improves retrieval-based chest X-ray report generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17579. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Nejatian, N.P.; Nasir-Moin, M.; Wang, D.; Abidin, A.Z.; Eaton, K.; Riina, H.A.; Laufer, I.; Punjabi, P.P.; et al. Health system-scale language models are all-purpose prediction engines. Nature 2023, 619, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, E.; Talius, E.; Patel, P.; Langlotz, C.P.; Ng, A.Y.; Rajpurkar, P. Expert-level detection of pathologies from unannotated chest X-ray images via self-supervised learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garadi, M.A.; Kim, S.; Guo, Y.; Warren, E.; Yang, Y.-C.; Lakamana, S.; Sarker, A. Natural language model for automatic identification of intimate partner violence reports from Twitter. Array 2022, 15, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yao, B.; Dong, Y.; Gabriel, S.; Yu, H.; Hendler, J.; Ghassemi, M.; Dey, A.K.; Wang, D. Mental-llm: Leveraging large language models for mental health prediction via online text data. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Levkovich, I. Beyond human expertise: The promise and limitations of ChatGPT in suicide risk assessment. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1213141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, H.; Matz, S.C. Large language models can infer psychological dispositions of social media users. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settanni, M.; Quilghini, F.; Toscano, A.; Marengo, D. Assessing the Accuracy and Consistency of Large Language Models in Triaging Social Media Posts for Psychological Distress. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 351, 116583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, D.; Quilqhini, F.; Settanni, M. Leveraging social media and large language models for scalable alcohol risk assessment: Examining validity with AUDIT-C and post recency effects. Addict. Behav. 2025, 168, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z. Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In Behavioral Addictions; Rosenberg, K.P., Feder, L.C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021, 114, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Demetrovics, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Grant, D.; Koning, I.; Rumpf, H.-J.; Spada, M.M.; Throuvala, M.; Van den Eijnden, R. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, D.; Sariyska, R.; Schmitt, H.S.; Messner, E.-M.; Baumeister, H.; Brand, M.; Kannen, C.; Montag, C. Exploring the associations between self-reported tendencies toward smartphone use disorder and objective recordings of smartphone, instant messaging, and social networking app usage: A correlational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Montag, C.; Mignogna, A.; Settanni, M. Mining digital traces of Facebook activity for the prediction of individual differences in tendencies toward social networks use disorder: A machine learning approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 830120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Brunborg, G.S.; Pallesen, S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacis, L.; De Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Mignogna, A.; Elhai, J.D.; Settanni, M. Distinguishing high engagement from problematic symptoms in Instagram users: Associations with big five personality, psychological distress, and motives in an Italian sample. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2024, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of February 2025, by Number of Monthly Active Users. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Hall, M.A.; Witten, I.H. The WEKA Workbench. Online Appendix for Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, 4th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R.; Zarate, D.; Brown, T.; Hein, K.; Stavropoulos, V. The Bergen–Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS): Longitudinal measurement invariance across a two-year interval. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 28, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Strong, C.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.C.; Leung, H.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D. Time invariance of three ultra-brief internet-related instruments: Smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS), Bergen social media addiction scale (BSMAS), and the nine-item internet gaming disorder scale-short form (IGDS-SF9) (study Part B). Addict. Behav. 2020, 101, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, D.A.; D’Onofrio, J. Common, uncommon, and novel applications of random forest in psychological research. Behav. Res. Methods 2023, 55, 2447–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Flint, J. Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Soc. Res. Update 2001, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

| GPT-4o | Gemini 1.5 Pro | Self-Report | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Min–Max | M | SD | Min–Max | M | SD | Min–Max | |

| Items | |||||||||

| Salience | 2.23 | 0.84 | 1–5 | 2.15 | 1.01 | 1–5 | 2.34 | 1.13 | 1–5 |

| Tolerance | 2.57 | 1.01 | 1–5 | 2.22 | 0.86 | 1–5 | 2.22 | 1.08 | 1–5 |

| Mood modification | 2.21 | 0.92 | 1–4 | 1.86 | 0.69 | 1–5 | 2.00 | 1.12 | 1–5 |

| Relapse | 1.83 | 0.80 | 1–5 | 1.24 | 0.66 | 1–5 | 1.81 | 1.07 | 1–5 |

| Withdrawal | 2.03 | 0.83 | 1–5 | 1.81 | 0.70 | 1–5 | 1.33 | 0.72 | 1–5 |

| Conflict | 1.44 | 0.57 | 1–4 | 1.33 | 0.73 | 1–5 | 1.73 | 1.01 | 1–5 |

| Total Score | 12.31 | 4.58 | 6–28 | 10.61 | 4.25 | 6–30 | 11.42 | 4.33 | 6–29 |

| Number of Weekly Posts | Number of Weekly Stories | Time Spent on Instagram | Followers | Following | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | Salience | 0.129 | 0.486 | 0.659 | 0.183 | 0.244 |

| Tolerance | 0.052 | 0.387 | 0.594 | 0.141 | 0.272 | |

| Mood modification | −0.007 | 0.460 | 0.447 | 0.113 | 0.241 | |

| Relapse | 0.039 | 0.460 | 0.610 | 0.144 | 0.257 | |

| Withdrawal | 0.022 | 0.390 | 0.699 | 0.125 | 0.212 | |

| Conflict | 0.019 | 0.473 | 0.661 | 0.134 | 0.241 | |

| Total Score | 0.047 | 0.479 | 0.660 | 0.153 | 0.268 | |

| GEMINI 1.5 Pro | Salience | 0.185 | 0.400 | 0.716 | 0.208 | 0.219 |

| Tolerance | 0.103 | 0.380 | 0.677 | 0.159 | 0.184 | |

| Mood modification | 0.123 | 0.403 | 0.739 | 0.213 | 0.204 | |

| Relapse | 0.169 | 0.379 | 0.757 | 0.231 | 0.119 | |

| Withdrawal | 0.111 | 0.376 | 0.750 | 0.210 | 0.197 | |

| Conflict | 0.073 | 0.315 | 0.804 | 0.156 | 0.083 | |

| Total Score | 0.142 | 0.413 | 0.808 | 0.214 | 0.188 | |

| Self-report | Salience | 0.068 | 0.244 | 0.232 | 0.093 | 0.141 |

| Tolerance | 0.063 | 0.223 | 0.200 | 0.038 | 0.101 | |

| Mood modification | 0.032 | 0.088 | 0.164 | 0.040 | 0.041 | |

| Relapse | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.141 | −0.013 | 0.031 | |

| Withdrawal | 0.098 | 0.169 | 0.099 | 0.022 | 0.111 | |

| Conflict | 0.043 | 0.094 | 0.154 | 0.022 | 0.109 | |

| Total Score | 0.074 | 0.200 | 0.240 | 0.050 | 0.124 |

| Self-Report | Gemini 1.5 Pro | GPT-4o |

|---|---|---|

| Items | ||

| Salience | 0.303 (p < 0.001) | 0.387 (p < 0.001) |

| Tolerance | 0.269 (p < 0.001) | 0.336 (p < 0.001) |

| Mood modification | 0.228 (p < 0.001) | 0.206 (p < 0.001) |

| Relapse | 0.111 (p = 0.001) | 0.206 (p < 0.001) |

| Withdrawal | 0.145 (p < 0.001) | 0.169 (p < 0.001) |

| Conflict | 0.129 (p < 0.001) | 0.243 (p < 0.001) |

| Total Score | 0.319 (p < 0.001) | 0.414 (p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marengo, D.; Settanni, M. Using Large Language Models to Infer Problematic Instagram Use from User Engagement Metrics: Agreement Across Models and Validation with Self-Reports. Electronics 2025, 14, 2548. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14132548

Marengo D, Settanni M. Using Large Language Models to Infer Problematic Instagram Use from User Engagement Metrics: Agreement Across Models and Validation with Self-Reports. Electronics. 2025; 14(13):2548. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14132548

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarengo, Davide, and Michele Settanni. 2025. "Using Large Language Models to Infer Problematic Instagram Use from User Engagement Metrics: Agreement Across Models and Validation with Self-Reports" Electronics 14, no. 13: 2548. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14132548

APA StyleMarengo, D., & Settanni, M. (2025). Using Large Language Models to Infer Problematic Instagram Use from User Engagement Metrics: Agreement Across Models and Validation with Self-Reports. Electronics, 14(13), 2548. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14132548